Abstract

Based on criminal career data of a sample of 601 police-identified outlaw motorcycle gang members and an age-matched comparison group of 300 non-gang affiliated motorcycle owners, the current analysis examines various dimensions of the criminal careers of outlaw bikers, including participation, onset, frequency, and crime mix. Results show that Dutch outlaw bikers are more often convicted than the average Dutch motorcyclist, and that these convictions not only pertain to minor offenses but also to serious and violent crimes. We find that outlaw bikers’ criminal careers differ from that of the average Dutch motorcyclist already during the juvenile and early adult years, but also – and more so – during the adult years. These results fit the enhancement hypothesis of gang membership and suggest that both selection of crime prone individuals in outlaw motorcycle gangs and facilitation of criminal behavior whilst in the gang are taking place.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite repeatedly being depicted as criminal gangs by the popular media and criminal justice agencies, outlaw motorcycle gangs or OMCGs, by words of their spokespersons or individual members, have always maintained that they are just clubs of motorcycle enthusiasts, of whom some admittedly have occasionally come into contact with the police. Yet, so it is claimed, while OMCG members are by no means saints, they are no more sinners than the average motorcyclist. Dutch outlaw motorcycle clubs are no exception to this rule, and numerous recent serious and highly mediatized criminal cases have been passed off as a few bad apples that should not be mistaken to have spoiled the entire basket (e.g. De la Haye 2013; Lensink and Husken 2011). Unconvinced by these pleas however, as of 2012 the Dutch ministry of Security and Justice made outlaw biker crime a top priority and has launched a raft of measures to obstruct OMCGs in their criminal endeavors (Kamerstukken 2012; Van Ruitenburg 2016). These – at times far reaching – policies are justified by arguing that outlaw motorcycle gangs are hotbeds of crime and that their members are disproportionally engaged in offending. OMCGs have reacted by stating that these policies greatly infringe on their civil rights, and above all, given that the claims on their criminal involvement are grossly exaggerated, are unfounded (De Jong 2014). According to a leading member of a Dutch OMCG "more members of the VVD [the political party of the ruling minister-president] are in jail, than members of our club" (De Hoogh 2013). As at present the data to back up the claims of either one of these parties is largely lacking, empirical research into the criminal careers of outlaw bikers can greatly benefit future policy efforts.

From a theoretical vantage point examining the criminal careers of OMCG members is similarly valuable. OMCGs share commonalities with both street gangs and organized crime groups, members of which have only sparsely been subjects of criminal career research and whose criminal trajectories may not fit those described for more commonly studied populations (Lacourse et al. 2003; Van Koppen et al. 2010a, b). Like street gangs and organized crime groups, OMCGs may provide members with the criminal opportunity structure that entices them to engage in crime or that leads them to persist in their criminal ways longer than they would have otherwise. On the other hand, given their violent public image, one might also expect that especially those criminally inclined are attracted to becoming OMCG members in the first place, giving the lie to the idea that OMCG membership alters one’s criminal career.

In a first exploration of these issues, this study uses official criminal data on 601 members of Dutch Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs and compares these with data of a random sample of 300 Dutch motorcycle owners. Criminal careers of OMCG members and motorcycle owners are then equaled on several criminal career dimensions, including participation, onset, frequency and crime mix.

What follows is a brief discussion of the theorized effects that membership of a street gang or organized crime group may have on individuals’ criminal trajectories. This literature leads us to pose four hypotheses concerning the prevalence and severity of criminal involvement among OMCG members compared to motorcyclists who are not OMCG members. In the section on the Dutch outlaw biker scene, the reader is presented with the necessary background information on Dutch outlaw biker clubs that have come under official scrutiny. After briefly reviewing the prior literature on OMCG crime, we provide information on the data source and methods of the current study, and present the results of our current analyses. In the final section we reflect on our findings in relation to the hypotheses stated in the introduction and their implications from a theoretical and policy viewpoint.

OMCGs, street gangs and organized crime groups

Whereas one can argue whether OMCGs are rightly labeled as ‘gangs’ in a criminological sense of the term (e.g. Klein 2002), or on the extent to which they fit (one of) the accepted definition(s) of an ‘organised crime’ group (e.g. Fijnaut et al. 1998), for the purpose of the current study it suffices to establish that OMCGs have apparent commonalities with both street gangs and organized crime groups that a priori seem theoretically relevant for understanding the criminal pathways of those involved in these groups. Therefore, for predictions on the criminal careers of OMCG members, we turn to these respective literatures.

Street gang membership and criminal careers

While street gangs come in many different shapes and sizes (see e.g. NGIC 2015), traditional US street gangs, like the Bloods and the Crips, are known for having a notable physical presence that is expressed by means of recognizable signals, like clothing style and tattoos (Klein 1996). Utilizing these signals, street gangs differentiate themselves not only from non-gang members, but also from members of rival gangs. Newcomers to the street gang are often expected to go through a hazing period, during which they have to show their commitment to the gang by carrying out all kinds of menial tasks and have to earn the trust of their elders by taking risks or carrying out specific criminal acts (Decker and Van Winkle 1996). Street gangs typically also try to control public space and delineate their turf by graffiti tags, defending it against infractions from other street gangs. For many street gang members intergang rivalry, and the violent pose associated with it, is a crucial part of their social identity (Goldman et al. 2014). As a group, many street gangs have been associated with violence and drug related crimes. Starting in the 1980s, a sizable body of research has also documented a positive association between street gang membership and the individual’s criminal behavior (Pyrooz et al. 2016).

This prior research found early externalizing and aggressive behavior to be risk factors for street gang membership (Klein and Maxson 2006). Street gang members generally also experience an earlier start and higher frequency of delinquency compared to non-gang members (Gordon et al. 2004; Melde and Esbensen 2013). Crime levels of gang members are particularly high during the actual period of gang membership (Thornberry et al. 1993). The difference between street gang members and non-street gang members is strongest for serious and violent crimes (Esbensen et al. 1993). Finally, juvenile street gang members are at increased risk of prolonged criminal involvement and adult incarceration (Thornberry et al. 2003). Interestingly, the association between street gang membership and offending is generally weaker in European compared to US samples (Pyrooz et al. 2016). Higher levels of gang organization and easy access to fire arms have been suggested to explain this difference (Esbensen and Weerman 2005; Decker and Pyrooz 2010). Given that European OMCGs are modeled after their US counterparts and fire arms also appear ubiquitous in the European outlaw biker milieu, whether this difference also holds for European compared to US OMCGs is an important empirical question.

Thornberry et al. (1993) identify three causal mechanisms as a result of which membership of a street gang may be associated with increased levels of criminal behavior. The first is selection, which posits that gangs either recruit youths that have shown a proclivity for crime and violence, or that those kinds of youths themselves are disproportionately attracted to becoming a gang member. These youths are likely to engage in delinquency and crime regardless of them being a gang member, and becoming a gang member has no causal effect on the youth’s criminal career. Based on the selection model, one would expect gang members to show higher levels of criminal involvement before, during as well as after their period of gang membership. The second causal mechanism is social facilitation. According to this model, gang members are not intrinsically different from non-gang members, yet upon becoming a gang member they subject themselves to the unique pushes and pulls toward crime that result from the structure and social processes that characterize street gangs. According to the facilitation view, becoming a gang member does causally influence youth’s criminal behavior, and while no different from non-gang members both before and after gang membership, the criminal behavior of youths while in the gang is expected to be more frequent and serious than that of non-gang members. Finally, Thornberry and colleagues leave open the possibility that processes of selection and facilitation may operate simultaneously, resulting in what they term enhancement. According to this view, crime prone individuals are disproportionately attracted to street gangs, yet while being in the gang, the criminal behavior of these individuals is also temporarily increased, and reaches levels higher than those equally inclined to crime but who are not gang members.

Organized crime and criminal careers

In contrast to street gangs, organized crime groups are most times less conspicuous, and more focused on (il)legal business. The classic view of organized crime groups as bureaucratic, mafia-style organizations, however has lost out to an entrepreneurial interpretation of organized crime in which individuals come together on profitable criminal markets to carry out certain criminal activities in loosely connected networks (Reuter 1983).Footnote 1 As by definition organized crime involves co-offenders, trust is a major issue for those engaged in organized crime (Arlacchi 1986). In the absence of strong affective family relationships, that feature prominently in some organized crime groups (Bruinsma and Bernasco 2004), a sound criminal reputation may also be taken to signal to a potential co-offenders’ trustworthiness (Von Lampe and Johansen 2004). As a result, organised crime groups may specifically recruit those that already have ample criminal experience. However, as organized crime is often logistically complex and has transnational components finding suitable co-offenders that have the skills and contacts to cloak illegitimate goods, transactions and profits behind a legitimate façade is also pivotal (Van Koppen and de Poot 2013). Having established these skills and contacts through a conventional career, individuals without considerable previous criminal involvement can therefore be of great worth to organized crime groups. Likewise, those having established a certain position through legal employment, may switch from legal to illegal business as opportunities for organized crime present themselves (Kleemans and de Poot 2008).

Very few studies have focused on the criminal careers of organized crime offenders. Using data from the Dutch Organized Crime Monitor, Kleemans and De Poot (2008) found that one in three organized crime offenders was over age 40 at the time of the organized crime offense that got them in the sample. Judged by their officially recorded criminal history the majority of these offenders had been criminally active for a period of over 10 years. The average age of onset for these organized crime offenders was 27. In an extended follow up study, Van Koppen et al. (2010b) compared the criminal careers of organized crime offenders to that of general offenders and found both groups to experience the onset of their criminal careers in their mid-twenties. The main difference between organized crime offenders and general offenders appeared to be the seriousness and duration of their offending. While organized crime offenders and general offenders with prior convictions at the time of sampling did not differ in the frequency of their prior offending, organized crime offenders were more often convicted to imprisonment and also experienced more and longer custodial spells than general offenders. Those ending up involved in organized crime thus seem more serious offenders from the start. Finally, a Home Office study into the criminal careers of organized crime offenders in the UK found that organized crime offenders did differ from general offenders – but not from serious offenders – in having an earlier onset, longer career duration and a higher offending frequency (Francis et al. 2013). Still, the majority of organized crime offenders could be characterized as ‘low rate’ offenders.

The literature on organized crime distinguishes two causal mechanisms that link participation in organized crime to the individual’s larger criminal career. The first, originally applied to explain participation in white collar crime, is that of punctuated situational dependent offending (Leeper Piquero and Benson 2004). According to this model those who react to the decreased levels of social control that characterize adolescence and young adulthood with delinquency and crime, are also more likely to engage in organized crime in adulthood when the opportunity to do so presents itself. The mechanism of punctuated situational offending, akin to that of selection into street gangs, thus predicts that those engaged in organized crime, were already more prone to react delinquent to changing opportunity structures during adolescence and are again – after a period of intermittency - when the incentive structure for, this time, organized crime changes during the adult years. A second mechanism, social opportunity structure, posits that individuals engage in organized crime, not because of some inherent proclivity, but rather as a result of the skills and social ties they acquire with age and through conventional activities, like employment or leisure activities (Kleemans and de Poot 2008). Especially since their conventional development was not hindered by disproportionate involvement in adolescent delinquency, they become valuable assets for recruitment by organized crime groups. Like the facilitation hypothesis, the mechanism of social opportunity structure predicts members of organized crime groups not to differ from the general population in terms of adolescent and young adult delinquency and crime, but only with respect to adult criminal behavior.Footnote 2

OMCG membership and criminal careers

OMCGs show features of both street gangs and organized crime groups. Like street gangs, OMCGs have a physical presence, signalled by the wearing of various OMCG insignia, most notably their colours – the sleeveless vest with the three piece back patch worn only by members -, by which they create and sustain a clear ‘us versus them’ perspective.Footnote 3 Similar to street gangs, OMCGs have an initiation period in which the prospect member has to prove to be worthy of membership (Barker 2015). Some OMCGs reportedly require prospect members to commit a crime, to prove loyalty to the gang as well as in order to minimize the risk of being infiltrated by government agents. Finally, intergang competition appears to be deeply ingrained into the fabric of OMCGs (Quinn and Forsyth 2007, 2011), increasing the risk of crime and violence among OMCG members, or, alternatively, increasing attraction of OMCG membership to crime prone or violent individuals. Yet, like organised crime groups, OMCGs typically consist of adult members and membership is not open to everyone. Also like organised crime groups, OMCGs have been repeatedly associated with more entrepreneurial types of crime, which consequently may increase OMCGs’ need for conventionally skilled co-offenders not priory involved in crime (Quinn and Koch 2003).

This leaves us with the basic research questions: are members of OMCGs different than ‘your average biker’ in terms of criminal involvement, and if yes, why could this be so? To explain OMCG members’ criminal involvement we turn to the above mentioned causal mechanisms offered in the street gang and organized crime literature. This translates in four hypotheses to be tested in the current analyses:

-

1.

Based on prior research on street gangs we expect that OMCG membership, like street gang membership, is associated with higher levels and seriousness of crime, and that, in terms of criminal involvement, OMCG members are thus different from ‘your average biker’.

In anticipation of results confirming this first hypothesis, we propose and test three different mechanisms by which the association between OMCG membership and crime may come about:

-

2.

If selection (or punctuated situational offending) is involved, members of an OMCG will differ from a random selection of motorcycle owners from an early age onward – that is well before they would have been members of an OMCG. If OMCG members show a higher prevalence, an earlier onset, higher frequency, and more serious mix of offending during their juvenile and early adult years than does the average motorcycle owner, we take this as evidence that selection into OMCG membership is at play.

-

3.

If facilitation (or social opportunity structure) explains the association between OMCG membership and crime, we expect no differences between OMCG members and the average Dutch motorcycle owner, in terms of the onset, frequency and seriousness of their juvenile and early adult delinquency. Yet, given that at some point in their adult lives OMCG members affiliated with an OMCG whereas the random group of motorcycle owners didn’t – or at least can be assumed to have done so to a far less extent – we do expect adult offending among OMCG members to be more prevalent, frequent, and serious than that of the average motorcycle owner.

-

4.

If enhancement is involved, OMCG members are expected to differ from the average motorcycle owner not only in the prevalence, onset, frequency, and seriousness of their juvenile and early adult offending, but also in the prevalence, frequency, and seriousness of their adult offending, even when differences in juvenile offending between these groups are accounted for.

The Dutch outlaw biker scene

The dawn of the Dutch outlaw biker scene can be traced back to the early seventies. In 1976, police inspector Dooms wrote a paper about upcoming biker groups in his district. The best known were the ‘Hells Angels’, although he also identified biker groups called Maddocks, Road hogs and Cannibles [sic]. These groups, inspired by movies and magazines depicting the US biker culture, consisted mostly of youths in their late teens and early twenties. These teens, who later became the ‘Hells Angels’ founding members, had their roots in the same infamous Amsterdam backstreet district (PEO 1996).

Dooms (1976) noticed how some young boys found these bikers (who were only marginally older) tremendously fascinating. These youngsters apparently wished to become bikers themselves as soon as possible, and were sometimes allowed to hitch a ride as a passenger. Dooms doesn’t describe what drove this attraction, but based on his description of the groups, it was likely their ‘heavy machinery’, outward (deviant) appearance and the intimidating effect they had on outsiders. Furthermore, he noticed, “the Hells Angels as a group were constantly looking for trouble” (Dooms 1976, p.17). Already during this early stage, the ‘Hells Angels’ became quite dominant and also started to absorb members of the other groups. In an understated manner Dooms (1976) noted that the defectors from other groups “were not those with the shortest list of antecedents” (p.13).

Recognition as an official chapter of the Hells Angels motorcycle club followed in 1978 when the mother organization in the United States gave its blessing. Viewed as exponents of a perceived ‘counterculture’ at that time, the city of Amsterdam even subsidized the club house of the newfangled outlaw bikers. Several incidents mark this early period, including the various alcohol and substance induced violent interactions with ‘citizens’, as non-members are referred to, and the alleged sexual abuse of a minor in the municipally supported Hells Angels clubhouse (Burgwal 2012).

The eighties and early nineties witness the establishment of several other Dutch outlaw biker clubs and a further growth of the Dutch Hells Angels. Most of these native clubs remain quite small, with only one or two chapters and a handful of members. Although it is rumored that OMCGs have become involved in protection rackets and drugs and arms trafficking, these rumors do not spark particular interest of criminal justice officials. Because street brawls and overt aggression against the police subside, the Dutch authorities largely leave the OMCGs alone.

Things start to change in 1996 when a parliamentary report on Dutch organized crime, describes the Amsterdam Hells Angels as taking part in crimes that are well organized. The Amsterdam Hells Angels are accused of trafficking synthetic drugs, Moroccan hashish, and fire arms, but also of carjacking, extortion and running protection rackets (PEO 1996). In 2000, the Hells Angels’ association with organized crime is again out on public display when hundreds of outlaw bikers join the funeral procession of a well-known figure in the Dutch underworld, who also was an Hells Angels prospect. Two months later this is followed by the physical intimidation by a group of Hells Angels of two anchormen of a popular late night talk show who had referred to the Hells Angels as a ‘criminal organization’ on their show. In the live broadcast that follows the anchormen, noticeably roughed up, apologize and retract their earlier statement. In yet another infamous incident, the president of the Limburg Hells Angels chapter along with two patched members are murdered by fellow club members in 2004, apparently because of a dispute involving a stolen shipment of Columbian cocaine (Schutten et al. 2004). It stands to reason that the buildup of events during this period attracts much attention from the authorities to OMCGs.

Meanwhile, to avoid violent intergang confrontations like the ones that had taken place in Canada and Scandinavia, in 1996 the Dutch OMCGs set up “the Council of Eight” (National Police of the Netherlands 2014). Its name refers to the eight official OMCGs that are active in the Netherlands during that time. The Council also has a say in which club can call itself an ‘MC’, who is allowed to wear the three piece back patch signifying outlaw status, and the extent of each club’s territory. In 2011 however, the indigenous Satudarah, the second biggest OMCG in the Netherlands at the time, walks out (although rumor has it that they were kicked out). When two other OMCGs also walk out, the Council is disbanded in 2013.

Following two failed attempts to get the Dutch Hells Angels banned as a criminal enterprise,Footnote 4 and confronted with a growing and increasingly instable outlaw biker scene and mounting suspicions that at least some of the Dutch OMCGs are involved in serious criminal activities, the Dutch government adapts its response to OMCGs to a whole-of-government approach (Kamerstukken 2012). This approach entails a comprehensive effort of different government bodies to use their respective powers to curb the outlaw biker scene, for instance by adopting more restrictive policies regarding licenses for club houses and motorcycle events, prohibiting OMCG members from working certain government jobs and looking at any tax irregularities (Van Ruitenburg 2017). After a period of relative leniency toward OMCG deviance, the Dutch OMCGs and their members are now under a magnifying glass.

Prior research on the criminal careers of outlaw bikers

Whereas street gangs are the subject of a substantial and growing scientific literature (Decker and Pyrooz 2015), academic interest in OMCGs is still limited (Lauchs et al. 2015). This is in a way surprising as their hybrid character, combining elements from both street gangs and organized crime groups, makes them ideally suited to contrast theories and predictions from both these literatures. Research into OMCG crime however has been plagued by a lack of empirical data, and research methods well suited to study juveniles affiliated with street gangs, like self-report surveys (Esbensen et al. 2001), are less obvious both to identify OMCG members and to chart their criminal behavior. To circumvent these data issues prior research resorted to media reports (Barker and Human 2009), confined itself to reports of prison misconduct (Ruddell and Gottschall 2011), or operationalised OMCG membership based on personal ads in the classified section of a biker magazine and the self-reported prevalence of motorcycles over cars as a means of transportation (Danner and Silverman 1986). To date, only a handful of studies used police intelligence to identify OMCG members, and also had access to officially registered criminal career data.

Tremblay et al. (1989) found that of the 1530 police identified members of one of the 62 OMCGs active in Quebec Canada between 1974 and 1988, 70% had a criminal record. Alain (1993, 1995), also using Canadian data, concludes that in terms of offending frequency and seriousness, the 1010 police identified OMCG members in his study do not differ from the general Canadian prison population. Both the Tremblay and Alain study however refer to the period before the ‘Canadian biker war’ (1994–2001), a violent conflict between the Hells Angels, the native OMCG Rock Machine, and later the Bandidos. The 1999 annual report from the Criminal Intelligence Service Canada (CISC), published in the midst of this intergang conflict, reports that of the 214 full-color members of the Canadian Hells Angels known to the CISC, 95.8% had a criminal record, with nearly half of these for drug-related offenses (cited in Barker 2015: 148). Citing police statistics, the Canadian Immigration and Refuge Board (IRB) mention 67.2% of Ontario Hells Angels have a criminal record, of which many drug-related (Humphreys 2012). Similar figures were reported by Canadian public prosecutors and judges in several court cases involving OMCGs (Barker 2015).

Following a period of violent conflict between Scandinavian OMCGs (1994–1997), outlaw bikers became a topic of research interest in Europe as well. Klement (2016a) mentions a Swedish study (BRÅ 1999) that found 75 out of a sample of 100 Swedish OMCG members had criminal records, the majority of which for threats and violence. Norwegian police data showed that in 2007, 69% of all known Norwegian OMCG members was convicted at least once. In 2010, depending on the club, this percentage ranged from 56 to 75% (National Police Directorate 2010). Klement and Pedersen (2013) studied early criminal careers of later Danish OMCG members and found that between ages 15 to 30 their average annual frequency of offending fluctuated between 2.5 and 4. A recent study based on a sample of 396 Danish OMCG members (Klement 2016a) found that 92% of these police identified outlaw bikers had a criminal record, while 69% were convicted for a violent offense at least once prior to age 30 or their registration in the Police Intelligence Database (PID) for being affiliated with an OMCG, whichever came first. In a follow up study (Klement 2016b) was able to match 297 OMCG members to 181,931 controls on age, age of first conviction, total number of convictions – for respectively all offenses, property offenses and violent offenses -, and days of sentenced prison time. Subsequently comparing the criminal careers of PID registered OMCG members after PID registration to the criminal careers of non-PID registered controls, this study showed OMCG membership to significantly increase the level of criminal involvement, especially for property crimes, drug crimes, and violations of the weapons act.

Finally, the first known study of the criminal careers of Dutch OMCG members, is the already mentioned study of Dooms (1976). Based on police briefings, he identifies 37 members of the Haarlem ‘Hells Angels’, a group of motorized youths that model their appearance and behavior after their American idols. As the first Dutch Hells Angels chapter was only officially recognized in 1978, these youths may not truly qualify as ‘OMCG member’, yet the finding that these 37 individuals together account for 138 criminal charges does illuminate the character of the youths involved in the Netherlands’ early biker scene. Since then, in several court cases aimed at banning particular OMCGs or chapters of OMCGs the Dutch public prosecutor also refers to high levels of criminal involvement among OMCG members. In one particular case the public prosecutor argued that 18 out of 23 members (78.2%) had a criminal record, of which many were lengthy and steeped in violence (ECLI:NL:RBMAA:2007:BA5843). In another court case it was argued that 84 out of 105 members (80%) had a criminal history. Together these members were responsible for 575 convictions, of which one in five related to violent offenses (ECLI:NL:RBLEE:2007:AZ9940). No benchmark however is presented, making it difficult to judge these figures in terms of the scale of OMCG members’ overrepresentation in crime.

In sum, the limited number of prior studies available suggests that a substantial proportion of OMCG members has had contact with the criminal justice system. Yet, in most studies a comparison group is lacking, so the extent to which the level of criminal involvement among OMCG members is disproportional compared to other populations cannot be ascertained. Furthermore, OMCG members are reported to engage in criminal behavior both before and after joining an OMCG so the causal significance of joining an OMCG for members’ criminal career development very much remains a question in need of empirical study (though see Klement 2016b).

Current study

The current study aims to overcome many of the short comings that plagued prior research. First, instead of being defined by a preference for reading biker magazines, or self-reported membership – which both may overestimate membership, OMCG membership is based on the visual confirmation by a sworn officer. Second, the current sample is not limited to a single club or chapter, but has members from all OMCGs that were known to be active in The Netherlands during the sampling period. Third, the current study makes use of an age-matched comparison group of non-OMCG members thus providing a benchmark to which the findings for OMCG members can be contrasted. Finally, it is based on official records that enable us to reconstruct the criminal careers of both OMCG members and the comparison group from 2013 all the way back to age 12, which is the minimum age of criminal responsibility in The Netherlands. The above features make the current study ideally suited to answer the study’s main research question: What are the main criminal career characteristics of members of Dutch Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, and how do these criminal career characteristics compare to those of non-members?

Data and methods

Sample

This study uses two datasets. The first is made available by the outlaw motorcycle gangs intelligence unit of the Central Criminal Investigations Division of the Netherlands National Police; a unit especially appointed by the Dutch ministry of Safety and Justice to accumulate intelligence on outlaw biker crime (Kamerstukken II 2011/12, 29,911, 71). The unit seeks to gather information on OMCGs on a strategic and tactical level, both to aid policy makers and to initiate police investigations when the commission of a crime is ascertained. Especially for this study the unit constructed a data file in which all police-known members of Dutch OMCGs are listed. This data file was constructed based on registrations in the police operational processes systems. Each registration in these systems refers to an observation that is officially recognized and registered by name of the observing police officer. For the current purpose to be considered a OMCG member the individual had to be officially registered as belonging to an OMCG – for instance based on the fact that he was seen wearing club colors, or was observed to regularly attend club meetings and social events. A conservative definition of membership was used meaning that the person’s identity must have been established by the police officer during that particular occasion, and that for instance the observation of OMCG members driving a particular car, would not lead to the registered owner of that car to be considered an OMCG member as well. Registrations in the police operational systems may result from different types of police action, like traffic stops, police reports, or observations made by community police officers and therefore not necessarily pertain to the person registered being suspected of a crime at that point in time. The consulted systems have a limitation period of five years, after which, if no new information is recorded, registrations are permanently deleted. For the current study this results in a data file pertaining to 601 individuals that were registered at least once between late 2007 and early 2013 as a member of one of the 12 OMCGs active in the Netherlands during that time. Importantly, despite the unique nature of the current sample, as neither the exact size or composition of the OMCG-membership is known, we have no way of establishing the extent to which the sample is statistically representative for the entire population of Dutch OMCG-members.

In order to obtain a reference group, we created a second dataset of motorcyclists not belonging to an OMCG. This second dataset was made possible by using the National Vehicle and Driving Licence Registration Authority database ‘light vehicles’. Because it was not possible to take a random sample of all motorcyclists in the Netherlands, we took a random sample of all motorcycle owners. Membership of an OMCG, after all, seems to suggest the ownership of a motorcycle.Footnote 5 On 8 October 2013, the date of our sample, the National Vehicle database contained 1,695,972 motorcycles in total. To limit the selection to male and living motorcycle owners, the registration holders were matched with Tax and Customs Administration on 8 October 2013. Next, we selected men whose year of birth fell in the same range as the years of birth of the outlaw bikers, and for whom no date of death had been registered. This yielded 1,243,362 registrations from which a random 300 persons were drawn and matched with individuals in the OMCG member dataset on the year of birth. None of these 300 motorcycle owners were at that time known to the police as outlaw bikers.

Criminal history data

The criminal careers of OMCG members and the comparison group of motorcycle owners were constructed using extracts from the Judicial Information System. These extracts include information on all criminal cases registered at the public prosecutor’s office and the way these cases were adjudicated. Here we include only those cases that ended in a guilty verdict, a prosecutorial fine, or a prosecutorial waiver for policy reasons. For reasons of brevity these outcomes will be referred to as ‘convictions’ in the remainder of this article. Cases that resulted in an acquittal or a prosecutorial waiver due to technicalities were excluded, as were cases pertaining to misdemeanors. Unlike operational data, the data we use here are not subject to periods of limitation. So, regardless of their age in 2013, we were able to reconstruct the criminal careers of the sample members from their current age all the way back to age 12 which constitutes the minimum age of criminal responsibility in the Netherlands. Besides the prevalence of convictions, these extracts also contain information on the nature of the offenses sample members were indicted for, and, if applicable, the type and severity of the sanction imposed.

Results

Do OMCG members differ from motorcycle owners?

Table 1 provides an overview of the personal and criminal careers characteristics of both the Dutch OMCG members and the age matched comparison group of male motorcycle owners. The vast majority of OMCG members is of Dutch origin, as is the comparison group. Country of birth may however not be very informative on the cultural backgrounds of OMCG members, as third and second-generation immigrants are also registered as Dutch-born. On average the Dutch OMCG member is in his mid-forties. The age distribution of OMCG members is highly skewed, with relatively few members under 35 and one in three police-identified OMCG members being aged fifty or older. Under the assumption that the likelihood of identification as an OMCG member is independent of age, this skewness in the age distribution may result from stringent qualifications for OMCG membership. It may also signal that in the five years prior to 2013 being an OMCG member appealed little to young people. As the comparison group was matched to represent the OMCG members with regard to their age in 2013, the comparison group does not differ from the OMCG members in this respect.

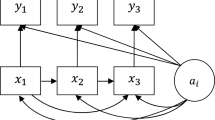

Based on the well documented association between street gang membership and crime, our first hypothesis was that membership of an OMCG was associated with higher participation, frequency and seriousness of offending, compared to the average motorcyclist (hypothesis 1). Our data show that over 82% of the Dutch OMCG members in our sample has acquired at least one registration in the Judicial Information System that resulted in what was defined as a conviction in this study. This percentage is over two-and-a-half times higher than that among the ‘average Dutch bikers’ in the comparison group. For many OMCG members, their criminal history is not limited to just one criminal justice contact. On average, those OMCG members that have a criminal history have been convicted 8.5 times between age 12 and their age in 2013. Those in the comparison group that have a criminal record are registered 4.4 times on average. Of the convicted OMCG members, 79.4% has been convicted at least three times, and 27.7% has been convicted 11 times or more. In the comparison group, those convicted are mostly convicted once or twice, and 78.3% is convicted five times or less. Figure 1 graphically depicts skewness of convictions in both samples by way of a Gini-plot – plotting what percentage of the sample (on the x-axis) is responsible for what percentage of all registered convictions for that particular sample (on the y-axis). If all sample members contributed equally to the sample’s total volume of convictions, the plotted curves would follow the diagonal – plotted as a dotted line in Fig. 1 as a reference. The more the observed line diverts from the diagonal, the more offending is concentrated in a small fraction of the sample committing a disproportionate amount of crime. Taking the entire sample into consideration the first pane of Fig. 1 seems to suggest that offending is much more skewed in the comparison group compared to OMCG members. However, as becomes apparent in the second pane of Fig. 1 which only looks at those sample members with a criminal history, this is mostly due to a greater proportion of the comparison group having no criminal record at all.

Further attesting to our finding that OMCG members differ from the average Dutch motorcyclist are the findings reported in Table 2. Table 2 looks at the outcome of criminal cases registered in the extracts of the Judicial Information System, which can be regarded as a proxy for offending seriousness.Footnote 6 Table 2 shows that over three quarters of the OMCG members was ever fined, and those who were, were so for around four times on average. This is more often than the comparison group of which less than half was ever fined, and of which those that were fined, were fined two-and-a-half times. In addition, more OMCG members – 36.2% - have spent time incarcerated, compared to our random sample of Dutch motorcycle owners – 8.2%.

To what extent can differences in criminal careers of OMCG members and motorcyclists be explained by selection?

To the extent that these differences between OMCG members and the average Dutch motorcyclist result from crime-prone individuals being drawn to OMCG membership (hypothesis 2), we would expect OMCG members to differ from the average motorcycle owner already in the onset, frequency and seriousness of juvenile/early adult offending – that is during an age period well before OMCG membership seems applicable. We find that the percentage of OMCG members that is convicted at least once prior to age 25 is over two-and-a-half times higher than that among the comparison group.Footnote 7 Convicted offenders in both groups however do not differ from each other in the age of onset of their criminal careers (Table 1). Figure 2 graphically depicts the cumulative onset age distribution for both the OMCG members and the comparison group. Given differences in the total number of convictions between the two samples, the second pane of Fig. 2 breaks this cumulative onset age curve into two groups – those offenders that end up having one or two convictions up to 2013, and those that accumulate three or more convictions. OMCG members with more extensive criminal careers experience an earlier onset of their criminal career than OMCG members with a maximum of two convictions. Yet, OMCG members do not differ from the comparison group in this respect. OMCG members convicted at least once prior to age 25 do differ from juvenile/early adult offenders in the comparison group in the frequency of their offending (Table 1). Also, the percentage of juvenile/early adult offenders convicted for a violent crime at least once is higher among OMCG members compared to the comparison group. Drug offending during these years is equally prevalent, yet also relatively rare, among young offenders from both samples.

To provide for a multivariate test of a possible difference in early criminal careers between OMCG members and the comparison group of Dutch motorcycle owners, we conducted a logistic regression predicting OMCG membership, simultaneously including indicators of participation, onset, frequency and seriousness of juvenile and early adult offending, while also controlling for age and country of birth. Results of this logistic regression, depicted as model 1 in Table 3, corroborate the univariate findings reported in Table 1 showing that OMCG members are both more likely to have an early criminal career and are more likely to engage in violent offending prior to age 25 than is the average Dutch motorcyclist. In fact, being registered for a violent offense prior to age 25 more than quadruples the odds of OMCG membership.

To what extent can in criminal careers of OMCG members and motorcyclists be explained by facilitation?

Our third hypothesis concerned differences between OMCG members and Dutch motorcyclists with respect to their adult criminal behavior, predicting that offending among OMCG members would be more prevalent, more frequent and more serious than among the average motorcycle owner (hypothesis 3). Results depicted in Table 1, show that this is indeed the case. The percentage of Dutch OMCG members having at least one adult criminal record is 2.8 times higher than that of average Dutch motorcyclists. The total number of adult convictions among OMCG members convicted as adults, as well as the percentage convicted for at least one violent offense after age 25 are almost double that of the comparison group. The percentage of adult offenders convicted for at least one drug offense is over six times higher in OMCG members compared to motorcycle owners. Table 1 also shows the average age of the last known offense to be higher for OMCG members, and the duration of their criminal career to be longer than that of the comparison group, though the latter difference is no longer significant when only recidivists are considered.

Figure 3 depicts the longitudinal age crime curve - or the average number of convictions registered at each age from ages 12 to 50 – for both the OMCG and the comparison sample. In the first pane of Fig. 3 the curves for both groups are plotted against the same y-axis, revealing a significant level difference between the two groups. From their teenage years onward, Dutch OMCG members show a considerable higher level of convictions than the comparison group of male motorcycle owners. As this level difference may obscure important differences in the shape of the age-crime curve for each of these two groups, the second pane of Fig. 3 again plots these age-crime curves, but now each on a separate y-axis. From the second pane of Fig. 3 it becomes clear that, beyond a level difference, the age-crime curve for OMCG members peaks at a later age than that of the comparison group. In the comparison group, conviction levels go down from the third decade of life onwards. Yet, for the OMCG members, the age-crime curve does not level off until these members are well in their forties.

To provide a multivariate test of our second hypothesis, we then conducted a logistic regression analysis to examine whether features of the adult criminal career predicted OMCG membership. Like before, controls for age and country of birth were included in these models. Results from the analyses, model 2 in Table 3, show that a higher number of adult convictions is associated with a higher likelihood of being registered as an OMCG member in the five years prior to 2013, as are being convicted for violence or drug offenses during the post age 25 years period. OMCG members have a six-fold higher odds of being registered for a drug offense compared to motorcyclists that are not OMCG members. Results from these multivariate analyses thus corroborate results from the univariate comparisons reported in Table 1, and indicate that OMCG members significantly differ from motorcycle owners in respect to their adult criminal careers.

To what extent can in criminal careers of OMCG members and motorcyclists be explained by enhancement?

Lastly, as a test of our fourth and final hypothesis, we estimated a model including both juvenile and adult criminal career features (hypothesis 4). We find that, once both juvenile and early adult and adult criminal career features are entered in the model, early violent offending, having an adult criminal career, and both adult violence and drug offending significantly predict OMCG membership. Having a juvenile/early adult record is no longer predictive of OMCG membership, however it must be kept in mind that, when having an adult criminal record is added to the model, the reference category for that variable changes from those that will never be convicted or have not yet been convicted by age 25 in model 1, to those never convicted in model 3. Similarly, the effect of having an adult criminal record in model 3 should be understood in reference to those never convicted during the follow up.Footnote 8,Footnote 9

Conclusion

Outlaw motorcycle gangs are increasingly perceived as a threat to public safety in the Netherlands and since 2012 coordinated efforts are made to reduce the allure of the outlaw biker lifestyle (Van Ruitenburg 2016). Unsurprisingly, outlaw bikers have objected to this whole-of-government approach, as they claim that, when it comes to crime, they are no different than your average motorcyclist. This study used a unique data set of 601 police identified members of Dutch OMCGs and 300 age-matched non-OMCG motorcycle owners to compare the criminal careers of outlaw bikers with that of the average Dutch motorcyclist. Our findings show that, like street gang membership, OMCG membership is positively associated with having a criminal record, as well as the length and seriousness of that record. In fact, OMCG members are over twice as likely to be convicted at least once, and those that are, are convicted twice as often as registered non-OMCG affiliated motorcyclists. Within the limits of the current sample, Dutch OMCG members thus appear to far from resemble your average motorcyclist when it comes to officially registered offending. Yet, despite an overall higher level of offending, variation in the amount of convictions is similar in the OMCG and comparison sample. This indicates that among themselves OMCG members differ, just like non-OMCG members, in the extent of their criminal careers.

We find that OMCG members are more likely than the non-members of the comparison sample to be convicted prior to age 25. OMCG members are also more likely to have committed at least one violent offense prior to that age. We have no information of the exact date of entry into the OMCG yet given that, based on the age distribution of our sample, OMCG membership seems highly unlikely prior to age 25, we take this to signal selection of already criminally inclined individuals into OMCGs.Footnote 10 Yet, we also find evidence of OMCG membership to increase the risk of adult offending compared to non-OMCG members. In particularly, OMCG members are more likely to be convicted of violent and drug offenses after age 25. These findings corroborate a crime facilitation perspective on OMCG membership. As both selection and facilitation appear to be at work in our sample, the causal mechanism behind the association between OMCG membership and crime is best characterized as enhancement, the process by which offending levels of already crime prone individuals is elevated above and beyond that what would be expected when these individuals had not joined an OMCG. Given the nature of our current data testing theoretical explanations on why and how OMCG membership enhances crime remains an object of future study.

Despite the unique nature of the current data, a number of caveats to the current study should be mentioned. Both the nature of the OMCG sample, as well as the lack of information on the total OMCG membership in the Netherlands, leave us oblivious to the extent to which the current sample is representative of the total Dutch OMCG membership. To the extent that outlaw bikers currently actively involved in offending are more likely to be identified as an OMCG members by the police and therefore are more likely to end up in our sample, this would upwardly bias our estimates of OMCG crime. However, given the increased attention to OMCGs in the Netherlands, merely being seen wearing OMCG colors is likely to attract the attention of the police also outside a direct criminal context which would counter such an overrepresentation of criminally involved outlaw bikers in our sample.

Criminal career estimates in our study were based on official data. Officially registered crime is likely a conservative measure of actual crime, as only a minority of all crimes result in conviction. This may be especially salient for more organized types of crime, like drug trafficking, where years of police investigation may result in just one conviction (see Weisburd and Waring 2001 for a similar argument considering white collar crime). Yet, official crime data are known to reflect both offender and system behavior. As combatting OMCG crime became a criminal justice priority in the Netherlands, OMCG members are likely to have been subjected to increased levels of surveillance compared to non-OMCG members which could have resulted in higher likelihood of arrest and conviction for OMCG members, regardless of development in their actual offending behavior.Footnote 11

While the comparison with a representative sample of motorcycle owners is informative, as it enabled us to weigh the claim that outlaw bikers are just motorcycle enthusiasts, from a criminological perspective, for future studies it would be preferred to create a comparison group matched on criminologically more relevant variables, like educational level and social status. This would shed light on whether regardless of these characteristics, membership of an outlaw motorcycle club is associated with elevated levels of crime and more extended criminal careers.

Finally, our data does not have data on the precise timing on entering and exiting the OMCG. From research on street gangs is becomes clear that, despite gang myth making to the contrary, gang membership is usually not for life. In fact, the typical duration of street gang membership appears to be only two to four years (Gatti et al. 2011; Pyrooz 2014). OMCG folklore similarly has it that one is a member of an OMCG ‘forever’, a period only shortened if one is forced to leave the OMCG ‘in bad standing’, which entails that all ties with former brothers are cut off and that all gang insignia – including tattoos – need to be discarded. While leaving the gang ‘in good standing’ is primarily reserved for those whose age or health no longer permits them to participate in the outlaw biker lifestyle. In reality however, affiliation with an OMCG appears much more transient (Barker 2015). If membership duration was short and adult offending also occurred prior or after actual membership, our results may have overestimated the effects of OMCG membership on adult crime. If however the timing of offending was to coincide with the exact timing and duration of OMCG membership, our analysis may also have underestimated the criminogenic effects of OMCG membership by comparing offending during the entire post 25 period. Furthermore, again in sharp contrast with biker folklore, OMCG members are regularly found to ‘club hop’, exchanging membership of one OMCG for the next. Given that different Dutch OMCGs have different criminal profiles (Blokland et al. 2017), the effect of membership on offending might be conditional on the particular OMCG.

The multi-pronged approach adopted by the Dutch government is partly aimed at making OMCG membership increasingly undesirable. Ironically, since the adoption of the whole-of-government approach the Netherlands has witnessed a steep increase in the number of active OMCGs and the number of local chapters. Prior to the Council of Eight being disbanded eight OMCGs were active in the Netherlands, together accounting for approximately 30 chapters. In 2014 the number of active OMCGs had increased to 16 totaling an estimated 128 chapters. Indigenous OMCGs, like Satudarah and No Surrender, even established 46 chapters abroad. This rapid expansion has led many OMCGs to abandon their prolonged screening periods and arguably has lowered the bar for OMCG membership (Quinn and Forsyth 2011). Furthermore, increased rivalry between expanding OMCGs and the perceived need for ‘foot soldiers’ in anticipated intergang conflict, may have given rise to a new generation of outlaw bikers, primarily selected for their violent inclination and for whom OMCG membership has a very different connotation. Apart from OMCG expansion, the Netherlands is also confronted with an unprecedented growth in official support or puppet clubs. Members of these support clubs may be strategically put to use by OMCG members to lower their own risk of arrest and conviction (Smith 2002), complicating what can be inferred from official registrations. Given these recent developments in the Dutch outlaw biker scene and to test theoretical assumptions regarding OMCG dynamics, future research would best also incorporate members of support and puppet clubs.

Notes

Although in some locations, a few of these ‘old-fashioned’ mafia groups still endure. See e.g. Paoli (2003).

However, how social opportunity structure affects the criminal careers of individuals who are born into and grow up in families engaged in organized crime is as yet largely unknown.

The OMCGs even go as far as to protect their insignia by registered trademarks.

The judge declared the petition in the first case inadmissible due to procedural mistakes and found the fundamental right of freedom of association in the second case too important to curtail (District Court Amsterdam, ECLI:NL:RBAMS:2007:BC0685; Supreme Court of the Netherlands, ECLI:NL:HR:2009:BI1124).

As is Australia (Lauchs et al. 2015), the Netherlands are however increasingly confronted with the ‘bikers without bikes’ phenomenon.

Whereas both stealing a bicycle and stealing a truckload of consumer goods would be registered under the same section of the criminal code, the more serious nature of the latter would likely be reflected by the severity of the penalty imposed.

Note that in absence of the exact date of becoming an OMCG member the present study uses age 25 as a cut-off point to create a proxy for distinguishing the periods of non-OMCG membership and OMCG membership. This more conservative cut-off compared to Klement (2016b) who used age 30, is based on the age distribution of Dutch OMCG members in the current sample.

Caution is however needed when making causal inferences from logistic regression as results may be biased by unobserved variables that may both affect the dependent variable and are correlated with the independent variables in the current model. Multicollinearity may also compromise causal inference. Additional tests however showed that multicollinearity was not a problem in our models.

In an additional test of the fourth hypothesis, we limited the analysis to the subsample of OMCG members and non-OMCG members that actually had a juvenile criminal record (N = 210) . Like before, the adult criminal record variables are positively associated with OMCG membership, yet only the estimate for adult violence approaches statistical significance (exp(B) = 3.726, p = 0.055). This may be due to the limited remaining sample size of which only 33 non-OMCG members had at least one juvenile conviction.

To the extent that the age distribution of our OMCG sample reflects the simple passing of time since youths from the first generation of Dutch outlaw bikers established their clubs, this assumption is compromised. While several founder members are still known to be active in the Dutch OMCG scene, the current size of OMCG membership suggests that the majority of current OMCG members joined an OMCG at a later stage.

Klement (2016b) uses arrests for possession of small quantities of illegal drugs as an indicator of police attention. Given that possession of user amounts of controlled substances will not result in a conviction in the Netherlands and our data only pertains to felonies, our data lack a reasonable proxy of potential differential police attention directed toward the OMCG versus the comparison group.

References

Alain M (1993) Les bandes de motards au Québec: hypothèses du déclin d'une population. Can J Criminol 34(4):407–435

Alain M (1995) The rise and fall of motorcycle gangs in Québec. Fed Probat 54(2):54–57

Arlacchi P (1986) Mafia business. Verso, London

Barker T (2015) Biker gangs and transnational organized crime. Anderson Publishing, Cincinnati

Barker T, Human KM (2009) Crimes of the big four motorcycle gangs. J Crim Just 37:174–179

Blokland A, Soudijn MRJ, Van der Leest W (2017) Outlaw bikers in the Netherlands: clubs, social criminal organizations, or gangs. In: Bain A, Lauchs M (eds) Understanding the outlaw motorcycle gangs: international perspectives. Carolina Academic Press, Durham, pp 91–114

BRÅ (1999) MC-brott. Brottförebyggande rådet, Stockholm

Bruinsma G, Bernasco W (2004) Criminal groups and transnational illegal markets: a more detailed examination on the basis of social network theory. Crime, Law & Social Change 41:79–94

Burgwal L (2012) Hells Angels in de lage landen. Just Publishers, Meppel

Cressey DR (1969) Theft of the nation. Harper & Row, New York

Danner TA, Silverman IJ (1986) Characteristics of incarcerated outlaw bikers as compared to nonbiker inmates. J Crime Justice 9(1):43–70

De Hoogh M (2013) Satudarah wordt ‘schijtziek’ van justitie. Nieuwe Revu 52:30–31

De Jong E (2014) Achter doodskoppen gaan gevoelige soldaten schuil. NRC, 5 mei 2014. http://www.nrcreader.nl/artikel/5404/achter-doodskoppen-gaan-gevoelige-soldaten-schuil

De la Haye M (2013) “Het is pure pesterij” - MC-Kopstukken hebben het gehad met politie en justitie. Panorama 37:15–21

Decker SH, Pyrooz DC (2010) Gang violence around the world; context, culture, and country. In: McDonald G (ed) Small arms survey 2010. Cambridge University Press, London, pp 129–155

Decker SH, Pyrooz DC (2015) The handbook of gangs. Wiley Blackwell, Chichester

Decker S, Van Winkle B (1996) Life in the gang: family, friends, and violence. Cambridge University Press, New York

Directorate NP (2010) The Norwegian police force’s efforts to combat outlaw motor cycle gangs, 2011 to 2015. National Police Directorate, Oslo

Dooms JJ (1976) Hell's Angels, ja of neen?: een criminologische verkenning van een groep jonge motorrijders te Haarlem. Nederlandse Politie Academie, Apeldoorn 1976

Esbensen F-A, Weerman F (2005) Youth gangs and troublesome youth groups in the United States and the Netherlands: a cross-national comparison. Eur J Criminol 2:5–37

Esbensen F-A, Huizinga D, Weiher AW (1993) Gang and non-gang youth: differences in explanatory factors. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 9:94–116

Esbensen F-A, Winfree LT, He N, Taylor TJ (2001) Youth gangs and definitional issues: when is a gang a gang, and why does it matter? Crime and Delinquency 47(1):105–130

Fijnaut C, Bovenkerk F, Bruinsma G, van de Bunt H (1998) Organized crime in the Netherlands. Kluwer Law International, The Hague

Francis B, Humphreys L, Kirby S, Soothill K (2013) Understanding Criminal Careers in Organized Crime Home Office Research Report:74

Gatti U, Haymoz S, Schadee HMA (2011) Deviant youth groups in 30 countries: results from the second international self-report delinquency study. International Criminal Justice Review 21:208–224

Goldman L, Giles H, Hogg MA (2014) Going to extremes: social identity and communication processes associated with gang membership. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 17(6):813–832

Gordon RA, Lahey BB, Kawai E, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP (2004) Antisocial behavior and youth gang membership: selection and socialization. Criminology 42:55–88

Humphreys, A. (2012) Hells Angels members deported as refugee board declares bike gang a criminal organization. National Post

Kamerstukken (2012) Bestrijding georganiseerde criminaliteit. Tweede Kamer, Vergaderjaar

Kleemans ER, de Poot CJ (2008) Criminal careers in organized crime and social opportunity structure. Eur J Criminol 5:69–98

Klein MW (1996) Gangs in the United States and Europe. European Journal of Criminal Policy and Research 4(2):63–80

Klein MW (2002) Street gangs: a cross-national perspective. In: Huff CR (ed) Gangs in America, 3rd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 237–254

Klein MW, Maxson CL (2006) Street gang patterns and policies. Oxford University Press, New York

Klement C (2016a) The prevalence and frequency of crime among Danish outlaw bikers. Scandinavian Journal of Criminology 17(2):131–149

Klement C (2016b) Outlaw biker affiliations and criminal involvement. Eur J Criminol 13(4):453–472

Klement C, Pedersen ML (2013) Rockere og bandemedlemmers kriminelle karrierer og netværk i ungdommen. Justitsministeriets Forskningskontor

Lacourse E, Nagin D, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Claes M (2003) Developmental trajectories of boys' delinquent group membership and facilitation of violent behaviors during adolescence. Dev Psychopathol 15(1):183–197

Lauchs M, Bain A, Bell P (2015) Outlaw motorcycle gangs; a theoretical perspective. Palgrave McMillan, Hampshire

Leeper Piquero N, Benson ML (2004) White collar crime and criminal careers: specifying a trajectory of punctuated situational offending. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 20:148–165

Lensink H, Husken M. (2011) No Angels: de macht van een paar hobby clubs. Vrij Nederland. https://www.vn.nl/no-angels-de-macht-van-een-paar-hobbyclubs/

Melde C, Esbensen F-A (2013) Gangs and violence: disentangling the impact of gang membership on the level and nature of offending. J Quant Criminol 29:143–166

National Gang Intelligence Center (2015) National Gang Report https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/national-gang-report-2015.pdf/view

National Police of the Netherlands (2014) Outlaw bikers in the Netherlands. DLIO, Woerden

Paoli L (2003) Mafia brotherhoods: organized crime, Italian style. Oxford University Press, New York

PEO (1996) Inzake opsporing: Enquête opsporingsmethoden, Bijlage VIII: deelonderzoek I onderzoeksgroep Fijnaut: Autochtone, allochtone en buitenlandse criminele groepen (Parlementaire Enquêtecommissie Opsporingsmethoden No. 0921.7371). Den Haag: Tweede kamer 1995–1996, 24 072

Pyrooz DC (2014) “from your first cigarette to your last dyin’ day”: the patterning of gang membership in the life-course. J Quant Criminol 30:349–372

Pyrooz DC, Turanovic JJ, Decker SH, Wu J (2016) Taking stock of the relationship between gang membership and offending. Criminal Justice and Behavior 43(3):365–397

Quinn JF, Forsyth CJ (2007) Evolving themes in the subculture of the outlaw biker. The International journal of Crime, Criminal Justice, and Law 2(2):145–158

Quinn JF, Forsyth CJ (2011) The tools, tactics, and mentality of outlaw biker wars. Am J Crim Justice 36:216–230

Quinn J, Koch DS (2003) The nature of criminality within one-percent motorcycle clubs. Deviant Behavior 24:281–305

Reuter P (1983) Disorganized crime. The economics of the visible hand. MIT Press, Cambridge

Ruddell R, Gottschall S (2011) Are all gangs equal security risks? An investigation of gang types and prison misconduct. Am J Crim Justice 36:265–279

Schutten H, Vugts P, Middelburg B (2004) Hells Angels in opmars: motorclub of misdaadbende? Monitor, Utrecht

Smith R (2002) Dangerous motorcycle gangs: a facet of organized crime in the mid-Atlantic region. Journal of Gang Research 9(4):33–44

Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Chard-Wierschem D (1993) The role of juvenile gangs in facilitating delinquent behavior. J Res Crime Delinq 30:55–87

Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Smith CA, Tobin K (2003) Gangs and delinquency in a developmental perspective. Cambridge University Press, New York

Tremblay P, Laisne S, Cordeau G, MacLean B, Shewshuck A (1989) Carrières Criminelles Collectives: Évolution d’une Population Délinquante (Les Groups de Motards). Criminologie 22:65–94

Van Koppen MV, de Poot CJ (2013) The truck driver who bought a café: offenders on their involvement mechanisms for organized crime. Eur J Criminol 10(1):74–88

Van Koppen MV, de Poot CJ, Blokland AAJ (2010a) Comparing criminal careers of organized crime offenders and general offenders. Eur J Criminol 7(5):356–374

Van Koppen V, de Poot CJ, Kleemans ER, Nieuwbeerta P (2010b) Criminal trajectories in organized crime. Br J Criminol 50:102–123

Van Ruitenburg T (2016) Raising barriers to ‘outlaw motorcycle gang-related events’. Underlining the difference between pre-emption and prevention, Erasmus Law Review, 3, 122-134.

Von Lampe K, Johansen PO (2004) Organized crime and trust: on the conceptualization and empirical relevance of trust in the context of criminal networks. Global Crime 6:159–184

Weisburd D, Waring E (2001) White-collar crime and criminal careers. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Blokland, A., van Hout, L., van der Leest, W. et al. Not your average biker; criminal careers of members of Dutch outlaw motorcycle gangs. Trends Organ Crim 22, 10–33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-017-9303-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-017-9303-x