Abstract

This study examines the dynamics of consumer–brand identification (CBI) and its antecedents in the context of the launch of a new brand. Three focal drivers of CBI with a new brand are examined, namely: perceived quality (the instrumental driver), self–brand congruity (the symbolic driver), and consumer innate innovativeness (a trait-based driver). Using longitudinal survey data, the authors find that on average, CBI growth trajectories initially rise after the introduction but eventually decline, following an inverted-U shape. More importantly, the longitudinal effects of the antecedents suggest that CBI can take different paths. Consumer innovativeness creates a fleeting identification with the brand that dissipates over time. On the other hand, company-controlled drivers of CBI—such as brand positioning—can contribute to the build-up of deep-structure CBI that grows stronger over time. Based on these findings, the authors offer normative guidelines to managers on consumer–brand relationship investment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While image and reputation are often examined as antecedents to identification in the management literature, we do not use them in our framework for two reasons. First, as Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) state, “the notion of customer-company identification is conceptually distinct from consumers’ identification with a company’s brands, its target markets, or, more specifically, its prototypical consumer.” Using image or reputation can often capture firm-based perceptions rather than brand perceptions that we are trying to capture. Second, prior research in marketing has suggested that perceived quality is closely related to the external cues such as brand image and brand reputation (e.g., Dodds et al. 1991; Keller 1993; Zeithaml 1988), suggesting the two to be interrelated. Given brand management literature that has supported brand prestige (Kuenzel and Halliday 2008) as an antecedent to brand identification, it would be redundant to include both perceived quality and brand image in the conceptual framework. Third, such redundancy also produces multicollinearity in the empirical model.

It might be argued that consumers may have difficulty in answering some of these questions without actual use. We believe this is not the case for our research context. First, brand identification is not contingent on actual use. For example, a consumer can identify with a luxury brand without being able to afford it. Second and most important, the survey questions captured the state of the customer–brand relationship in the respective time period.

These time-varying covariates can also be modeled in the same way as we did for CBI antecedents to show how their effects interact with time from the initial stage. However, the effects of these variables are not the focus of our study. In addition, such specification will increase the number of parameters to be estimated, thus less parsimonious than the model we chose.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. New York: The Free Press.

Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34, 347–356.

Agustin, C., & Singh, J. (2005). Curvilinear effects of consumer loyalty determinants in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing Research, 52, 96–108.

Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Gruen, T. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: expanding the role of relationship marketing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 574–85.

Arnould, E. J., & Thompson, C. J. (2005). Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): twenty years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 868–882.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H. & Corley, K.G. (2008). Identification in organizations: an examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34, 325–374.

Ashforth, B. E., & Johnson, S. A. (2001). Which hat to wear? The relative salience of multiple identities in organizational contexts. In M. A. Hogg & D. J. Terry (Eds.), Social identity processes in organizational contexts (pp. 31–48). Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Dholakia, U. M. (2006). Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. International Journal of Research Marketing, 23, 45–61.

Baumgartner, H., & Steenkamp, J. B. E. M. (1996). Exploratory consumer buying behavior: conceptualization and measurement. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13, 121–137.

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 139–168.

Bergami, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2000). Self-categorization, affective commitment, and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 555–577.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer–company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67, 76–88.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Rao, H., & Glynn, M. A. (1995). Understanding the bond of identification: an investigation of its correlates among art museum members. Journal of Marketing, 59, 46–57.

Brown, T. J., Barry, T. E., Dacin, P. A., & Gunst, R. F. (2005). Spreading the word: investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33, 123–38.

Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28, 307–319.

Donavan, T. D., Janda, S., & Suh, J. (2006). Environmental influences in corporate brand identification and outcomes. Journal of Brand Management, 14, 125–136.

Donavan, T. D., Brown, T. J., & Mowen, J. C. (2004). Internal benefits of service-worker customer orientation: job satisfaction, commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 68, 128–46.

Dukerich, J. M., Golden, B. R., & Shortell, S. M. (2002). Beauty is in the eye of the beholder: the impact of organizational identification, identity, and image on the cooperative behaviors of physicians. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 507–533.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239–63.

Elliott, R., & Wattanasuwan, K. (1998). Brands as symbolic resources for the construction of identity. International Journal of Advertising, 17, 131–144.

Erdem, T., Swait, J., & Valenzuela, A. (2006). Brands as signals: a cross-country validation study. Journal of Marketing, 70, 34–49.

Escalas, J. E., & Bettman, J. R. (2005). Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. Journal of Consumer Research, 32, 378–89.

Fournier, S. (1998). Consumers and their brands: developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 343–373.

Gardner, B. B., & Levy, S. J. (1955). The product and the brand. Harvard Business Review, 33, 33–39.

Golder, P. N., & Tellis, G. J. (2004). Growing, growing, gone: cascades, diffusion, and turning points in the product life cycle. Marketing Science, 23, 207–218.

Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Batra, R. (2004). When corporate image affects product evaluations: the moderating role of perceived risks. Journal of Marketing Research, 51, 197–205.

Henry, K. B., Arrow, H., & Carini, B. (1999). A tripartite model of group identification: theory and measurement. Small Group Research, 30, 558–581.

Herzberg, F. (1966). Work and the nature of man. Cleveland: World Publishing Company.

Hogg, M. A. (2003). Social identity. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 462–479). New York: The Guilford Press.

Holt, D. B. (2002). Why do brands cause trouble? A dialectical theory of consumer culture and branding. Journal of Consumer Research, 29, 70–90.

Homburg, C., Wieseke, J., & Hoyer, W. D. (2009). Social identity and the service-profit chain. Journal of Marketing, 73, 38–54.

Houston, F., & Gassenheimer, J. (1987). Marketing and exchange. Journal of Marketing, 51, 3–18.

Jap, S. D., & Anderson, E. (2007). Testing a life-cycle theory of cooperative interorganizational relationships: movement across stages and performance. Management Science, 53, 260–275.

Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24, 163–204.

Keller, K. L. (2008). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57, 1–22.

Keller, K. L., & Lehmann, D. R. (2006). Brands and branding: research findings and future priorities. Marketing Science, 25, 740–759.

Kleine, S. S., Kleine, R. E., III, & Allen, C. T. (1995). How is a possession “me” or “not me”? Characterizing types and antecedents of material possession attachment. Journal of Consumer Research, 22, 327–43.

Kuenzel, S., & Halliday, S. V. (2008). Investigating antecedents and consequences of brand identification. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 17, 293–304.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 480–98.

Lecky, P. (1945). Self-consistency: A theory of personality. New York: Island Press.

Levinger, G. (1979). Toward the analysis of close relationships. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16, 510–44.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103–123.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

Maxham, J. G., III, Netemeyer, R. G., & Lichtenstein, D. R. (2008). The retail value chain: linking employee perceptions to employee performance, customer evaluations, and store performance. Marketing Science, 27, 147–167.

Mick, D. G., & Fournier, S. (1998). Paradoxes of technology: consumer cognizance, emotions, and coping strategies. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 123–143.

Mittal, B. (2006). I, me, and mine: how products become consumers’ extended selves. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 5, 550–62.

Netemeyer, R. G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., Ricks, J., & Wirth, F. (2004). Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 57, 209–224.

Oyserman, D. (2009). Identity–based motivation: implications for action-readiness, procedural-readiness, and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19, 250–260.

Park, C. W., Jaworski, B. J., & MacInnis, D. J. (1986). Strategic brand concept-image management. Journal of Marketing, 50, 135–45.

Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., & Priester, J. R. (2009). Research directions on strong brand relationships. In D. J. MacInnis, C. W. Park, & J. R. Priester (Eds.), Handbook of brand relationships (pp. 379–91). Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J. R., Eisingerich, A. B., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74, 1–17.

Pratt, M. G. (2000). The good, the bad, and the ambivalent: managing identification among Amway distributors. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45, 456–93.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Reed, A. (2004). Activating the self-importance of consumer selves: exploring identity salience effects on judgments. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 286–295.

Rindfleisch, A., Malter, A. J., Ganesan, S., & Moorman, C. (2008). Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: concepts, findings, and guidelines. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, 261–279.

Rousseau, D. (1998). Why workers still identify with organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 217–233.

Schau, H. J., & Gilly, M. C. (2003). We are what we post? Self-presentation in personal web space. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 385–404.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437–53.

Shavitt, S., Torelli, C. J., & Wong, J. (2009). Identity-based motivation: constraints and opportunities in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19, 261–266.

Shavitt, S. (1992). Evidence for predicting the effectiveness of value-expressive versus utilitarian appeals: a reply to Johar and Sirgy. Journal of Advertising, 21, 47–51.

Sheth, J. N., & Parvatiyar, A. (1995). Relationship marketing in consumer markets: antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23, 255–271.

Sirgy, M. J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behavior: a critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 287–300.

Sirgy, M. J., Johar, J. S., Samli, A. C., & Claiborne, C. B. (1991). Self-congruity versus functional congruity: predictors of consumer behavior. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 19, 363–375.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: SAGE Publications.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., ter Hofstede, F., & Wedel, M. (1999). A cross-national investigation into the individual and national cultural antecedents of consumer innovativeness. Journal of Marketing, 63, 55–69.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., & Gielens, K. (2003). Consumer and market drivers of the trial probability of new consumer packaged goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 368–384.

Stryker, S. (1968). Identity salience and role performance: the relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 30, 558–564.

Swan, J. E., & Combs, L. J. (1976). Product performance and consumer satisfaction: a new concept. Journal of Marketing, 40, 25–33.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33, 1–39.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1985). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Tellis, G. J. (1988). Advertising exposure, loyalty and brand purchase: a two stage model of choice. Journal of Marketing Research, 15, 134–144.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68, 1–17.

Walker, B. A., & Olson, J. C. (1991). Means-end chains: connecting products with self. Journal of Business Research, 22, 111–118.

Wolf, M. G. (1970). Need gratification theory: a theoretical reformulation of job satisfaction/dissatisfaction and job motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 54, 87–94.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52, 2–22.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Prof. Wynn Chin for the PLS Graph license and Insites Consulting, Belgium, for its support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Construct measures

Appendix: Construct measures

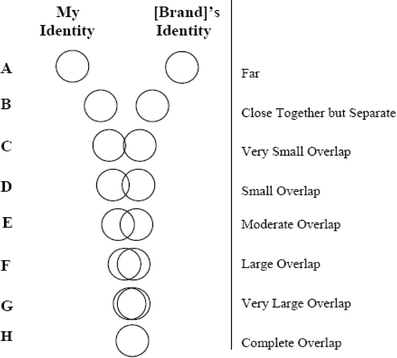

CBI (adapted from Bagozzi and Dholakia 2006; Bergami and Bagozzi 2000)

Cognitive CBI

-

CBI1.

(Venn-diagram item, where iPhone is the brand). We sometimes identify with a brand. This occurs when we perceive a great amount of overlap between our ideas about who we are as a person and what we stand for (i.e., our self identity) and of whom this brand is and what it stands for (i.e., the brand’s identity). Imagine that the circle at the left in each row represents your own personal identity and the other circle, at the right, represents the IPHONE’s identity. Please indicate which case (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, or H) best describes the level of overlap between your identity and the IPHONE’s identity. (Choose the Appropriate Letter).

-

CBI2.

(Verbal item). To what extent does your own sense of who you are (i.e., your personal identity) overlap with your sense of what the iPhone represents (i.e., the iPhone’s identity)? Anchored by: -4 = Completely different, 0 = Neither similar nor different, and 4 = Completely similar.

Affective CBI (7-point Likert, strongly disagree/strongly agree)

-

CBI3.

When someone praises [brand], it feels like a personal compliment.

-

CBI4.

I would experience an emotional loss if I had to stop using [brand].

Evaluative CBI (7-point Likert, strongly disagree/strongly agree)

-

CBI5.

I believe others respect me for my association with [brand].

-

CBI6.

I consider myself a valuable partner of [brand].

Perceived Quality (adapted from Netemeyer et al. 2004)

To what extent do you agree/disagree with the following statements, using 1: strongly disagree, and 7: strongly agree):

-

QUA1.

Compared to other brands of (product), [brand] is of very high quality.

-

QUA2.

[Brand] is the best brand in its product class.

-

QUA3.

[Brand] consistently performs better than all other brands of (product).

Self–Brand Congruity (adapted from Aaker (1997) brand personality scale)

How do you perceive the following characteristics for [brand] and yourself? Congruity scores for each dimension are reverse-coded of the Euclidean scores between self and the brand.

-

SBC1.

Sincere (e.g., down to earth, honest, genuine)

-

SBC2.

Exciting (e.g., daring, spirited, young, up-to-date)

-

SBC3.

Competent (e.g., reliable, efficient, leader)

-

SBC4.

Sophisticated (e.g., glamorous, charming, upper class)

-

SBC5.

Rugged (e.g., tough, strong, outdoorsy)

Consumer Innate Innovativeness (adapted from Steenkamp and Gielens 2003; 7-point Likert, “strongly disagree/strongly agree”; positively-worded items)

-

INNOV1.

In general, I am among the first to buy new products when they appear on the market.

-

INNOV2.

I enjoy taking chances in buying new products.

-

INNOV3.

I am usually among the first to try new brands.

Promotion (Please rate the extent to which you agree/disagree with the following statements about brand promotion of the new brand, using 1: strongly disagree, and 7: strongly agree, 5 waves)

-

PROM1.

This brand has offered attractive sales promotion offers during the past two months.

-

PROM2.

There has been a lot of advertising about this brand in the past two months.

Word-of-Mouth (Please rate the extent to which you disagree/agree with the following statement about word of mouth about the new brand, using 1: strongly disagree, and 7: strongly agree, 5 waves)

-

WOM1.

There has been a lot of media coverage about this brand.

-

WOM2.

My friends have been talking positively about this brand.

-

WOM3.

I am aware that there has been a lot of buzz about this brand.

-

WOM4.

My friends have highly recommended this brand.

Brand Improvement (Please rate the extent to which you disagree/agree with the following statement about the improvement of the new brand, using 1: strongly disagree, and 7: strongly agree, 5 waves)

-

IMP1.

During the past two months, this brand has made significant improvements.

-

IMP2.

I am fully aware of the new features that this brand has introduced in the past two months.

-

IMP3.

I really like the improvements that this brand has made in the past two months.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lam, S.K., Ahearne, M., Mullins, R. et al. Exploring the dynamics of antecedents to consumer–brand identification with a new brand. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 41, 234–252 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0301-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0301-x