Abstract

In this paper, we investigate the impact of US uncertainty shocks on GDP growth in nine small open economies: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. We compare the impact of two types of shocks: i) stock market volatility shocks and ii) policy uncertainty shocks. Using quarterly data from 1986Q1 to 2016Q1, this issue is analysed using Bayesian VAR models. Our results suggest that policy uncertainty seems to matter more than stock market volatility. Stock market volatility shocks appear to robustly have significant effects on Danish GDP growth. Policy uncertainty shocks, on the other hand, reliably lowers GDP growth in all five Nordic countries in a statistically significant manner. Statistically significant effects of policy uncertainty shocks on the Anglo-Saxon countries in our sample are harder to establish and are, in our preferred specification, only found for the United Kingdom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This has shown to be useful from a forecasting perspective; see, for example, Beechey and Österholm (2010).

See, for example, Cogley and Sargent (2001), Ribba (2006) and Österholm (2012).

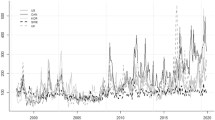

The reason for this is that the VXO is available starting 1986Q1 and the VIX is only available from 1990Q1. We argue that the longer time series is to be preferred. It can be noted that the correlation between the VXO and the VIX for the common sample is 0.99 (at the quarterly frequency).

Data on the unemployment rate, CPI and Fed funds rate were supplied by the National Institute of Economic Research. GDP data were supplied by the OECD. Data on the VXO were sourced from the FRED database at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Loius. Policy uncertainty data were downloaded from http://www.policyuncertainty.com/.

These values were suggested already by Taylor (1993) in his groundbreaking paper on monetary policy rules.

This stands in contrast to studies where the shocks are given a structural interpretation, such as aggregate demand shocks, aggregate supply shocks, wage setting shocks and monetary policy shocks. See Blanchard (1989) for an example and Amisano and Giannini (1997) for a more general discussion of identification in VAR models.

This is based on a fairly commonly employed principle where slow-moving variables appear before fast-moving ones. The recursive structure for identification was also used in Sims (1980) original article on VARs.

The standard deviation of the VXO shock is 5.1 units.

The standard deviation of the policy uncertainty shock is 15.2 units.

This parameter of exogenity tightness is set to 0.001.

These data were supplied by the OECD.

Results are not reported but are available from the authors upon request.

Having moved to year-on-year growth rates, we have to change the steady state priors for the variables concerned. We set the 95% prior interval to (2, 3) in all countries. For US CPI inflation the corresponding interval is given by (0.5, 3.5).

References

Aastveit KA, Natvik GJ, Sola S (2013) Economic Uncertainty and the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy. Norges Bank Working Paper 2013/17

Adler G, Djigbenou M-L, Sosa S (2016) Global financial shocks and foreign asset repatriation: do local investors play a stabilizing role? J Int Money Financ 60:8–28

Adolfson M, Laséen S, Lindé J, Villani M (2007) Bayesian estimation of an open economy DSGE model with incomplete pass-through. J Int Econ 72:481–511

Amisano G, Giannini C (1997) Topics in structural VAR econometrics, 2nd edn. Springer Verlag, Heidelberg

Artis M, Galvão AB, Marcellino M (2007) The transmission mechanism in a changing world. J Appl Econ 22:39–61

Bagliano F, Morana C (2010) Business cycle comovement in the G-7: common shocks or common transmission mechanisms? Appl Econ 42:2327–2345

Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ (2015) Measuring economic policy uncertainty, NBER Working Paper 21633

Bayoumi T, Swiston A (2009) Foreign entanglements: estimating the source and size of spillovers across industrial countries. IMF Staff Pap 56:353–383

Beechey M, Österholm P (2008) A Bayesian VAR with informative steady-state priors for the Australian economy. Econ Rec 84:449–465

Beechey M, Österholm P (2010) Forecasting inflation in an inflation targeting regime: a role for informative steady-state priors. Int J Forecast 26:248–264

Bernanke B (1983) Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment. Q J Econ 98:85–106

Blanchard OJ (1989) A traditional interpretation of macroeconomic fluctuations. Am Econ Rev 79:1146–1164

Bloom N (2009) The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica 77:623–685

Bloom N, Bond S, van Reenen J (2007) Uncertainty and investment dynamics. Rev Econ Stud 74:391–415

Caldara D, Fuentes-Albero C, Gilchrist S, Zakrajsek E (2016) The macroeconomic impact of financial and uncertainty shocks, NBER Working Paper 22058. http://www.nber.org/papers/w22058

Colombo V (2013) Economic policy uncertainty in the US: does It matter for the euro area? Econ Lett 121:39–42

Congressional Budget Office (2015) The budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025

Doan TA (1992) RATS Users Manual Version 4

Erten B (2012) Macroeconomic transmission of Eurozone shocks to emerging economies. Int Econ 131:43–70

Ferderer JP (1993) The impact of uncertainty on aggregate investment spending: an empirical analysis. J Money Credit Bank 25:30–48

Forbes KJ, Chinn MD (2004) A decomposition of global linkages in financial markets over time. Rev Econ Stat 86:705–722

Gilchrist S, Sim JW Zakrajsek E (2014) Uncertainty, Financial frictions, and investment dynamics. NBER Working Paper No. 20038

Hájek J, Horváth R (2016) The Spillover effect of euro area on central and Southeastern European economies: a global VAR approach. Open Econ Rev 27:359–385

Hofmann B, Takáts E (2015) International monetary Spillovers. BIS Q Rev 2015:105–118

International Monetary Fund (2013) Spillovers from policy uncertainty in the United States and Europe. World Economic Outlook, April 2013

Klößner S, Sekkel R (2014) International Spillovers of policy uncertainty. Bank of Canada Working Paper 2014–57

Leahy J, Whited T (1996) The effects of uncertainty on investment: some stylized facts. J Money Credit Bank 28:64–83

Leland HE (1968) Saving and uncertainty: the precautionary demand for saving. Q J Econ 82:465–473

Neely CJ (2015) Unconventional monetary policy had large international effects. J Bank Financ 52:101–111

Nicar S (2015) International Spillovers from U.S. Fiscal Policy Shocks. Open Econ Rev 26:1081–1097

Österholm P (2012) The limited usefulness of macroeconomic Bayesian VARs when forecasting the probability of a US recession. J Macroecon 34:76–86

Österholm P, Zettelmeyer J (2008) The effect of external conditions on growth in Latin America. IMF Staff Pap 55:595–623

Pesaran MH, Schuermann T, Weiner SM (2004) Modeling regional interdependencies using a global error-correcting macroeconometric model. J Bus Econ Stat 22:129–162

Sims CA (1980) Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica 48:1–48

Stockhammar P, Österholm P (2016) Effects of US policy uncertainty on Swedish GDP growth. Empir Econ 50:443–462

Stockhammar P, Österholm P (2016) The impact of US uncertainty shocks on small open economies. Working Paper No. 2016:5, School of Business, Örebro University

Taylor JB (1993) Discretion versus policy rules in practice. Carn-Roch Conf Ser Public Policy 39:195–214

Villani M (2009) Steady-state priors for vector Autoregressions. J Appl Econ 24:630–650

Villani M, Warne A (2003) Monetary policy analysis in a small open economy using Bayesian Cointegrated Structural VARs. Working Paper No. 296, European Central Bank

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are grateful to two anonymous referees for comments on this paper.

Appendix

Appendix

Impulse response functions of BVAR model with variables given by Eqs. (1) and (7)/(8). Estimated effects on GDP growth in the Anglo-Saxon countries. Note: Percentage points on the vertical axis and quarters on the horizontal axis. Black line is the median and the coloured band is the 90% confidence band

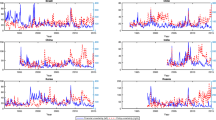

Impulse response functions. Estimated effects on GDP growth in the Nordic countries of BVAR model using year-on-year growth rates for GDP and CPI. Note: Percentage points on the vertical axis and quarters on the horizontal axis. Black line is the median and the coloured band is the 90% confidence band

Impulse response functions. Estimated effects on GDP growth in the Anglo-Saxon countries of BVAR model using year-on-year growth rates for GDP and CPI. Note: Percentage points on the vertical axis and quarters on the horizontal axis. Black line is the median and the coloured band is the 90% confidence band

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stockhammar, P., Österholm, P. The Impact of US Uncertainty Shocks on Small Open Economies. Open Econ Rev 28, 347–368 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-016-9424-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-016-9424-x