Abstract

Suppletion for case and number in pronominal paradigms shows robust patterns across a large, cross-linguistic survey. These patterns are largely, but not entirely, parallel to patterns described in Bobaljik (2012) for suppletion for adjectival degree. Like adjectival degree suppletion along the dimension positive < comparative < superlative, if some element undergoes suppletion for a category X, that element will also undergo suppletion for any category more marked than X on independently established markedness hierarchies for case and number. We argue that the structural account of adjectival suppletive patterns in Bobaljik (2012) extends to pronominal suppletion, on the assumption that case (Caha 2009) and number (Harbour 2011) hierarchies are structurally encoded. In the course of the investigation, we provide evidence against the common view that suppletion obeys a condition of structural (Bobaljik 2012) and/or linear (Embick 2010) adjacency (cf. Merchant 2015; Moskal and Smith 2016), and argue that the full range of facts requires instead a domain-based approach to locality (cf. Moskal 2015b). In the realm of number, suppletion of pronouns behaves as expected, but a handful of examples for suppletion in nouns show a pattern that is initially unexpected, but which is, however, consistent with the overall view if the Number head is also internally structurally complex. Moreover, variation in suppletive patterns for number converges with independent evidence for variation in the internal complexity and markedness of number across languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is one possible counter-example among adjectives of quality from Basque, and a handful of possibly challenging examples from quantifiers: ‘many/much–more–most.’ See Bobaljik (2012) for discussion and alternative accounts consistent with the generalisations presented in the main text. In this study we only take into account morphological, or synthetic, constructions and make no predictions for periphrastic constructions.

Bobaljik (2012:Chapter 7) proposes that the containment Hypothesis is itself a consequence of a deeper condition on the content of functional nodes. Specifically, it is proposed that UG cannot combine the comparative operator more and the universal quantifier inherent in the superlative thanallothers into a single functional node (cf. Kayne’s 2005:212, Principle of Decompositionality).

Note that of course not all constructions contain a superlative projection; as such, a comparative is represented as [[ adjective ] comparative ].

Note that for the exponents in the VI-rules here, and below, we abstract away from phonological details, and represent them orthographically.

Note that there is no competition or blocking among whole words; the form *gooder is never derived. See Embick and Marantz (2008) for discussion and comparison with alternatives.

Additional minor rules are needed to ensure that the superlative surfaces as best and not *betterest—see Bobaljik (2012) for discussion. What is relevant for the illustrative point here is that the comparative and superlative share a common root. Since ABC patterns are describable (see immediately below), it is formally possible to mimic a surface ABA pattern, via accidental homophony of A and C. Bobaljik proposes (Bobaljik 2012:35) to exclude this via a general learning bias against root homophony.

Here and below, we will treat the person formative as the ‘root’ of the pronoun; this is intended loosely as the most deeply embedded morpheme in the pronoun and the one that undergoes suppletion in the cases of interest. We do not intend to take a stand on whether pronouns have roots in some of the technical senses of that term.

See in particular Corbett (2005) for an extended argument that alternations in number for pronouns, such as Isg ∼ wepl are genuine instances of suppletion.

Caha argues that there is a unique, total ordering of containment relations amongst the oblique cases. We do not make that assumption here and allow instead for different obliques to be built from the dependent case, rather than from each other, as suggested by the transparent containment relations in Romani in Table 5, where dative and locative both contain the accusative, but neither contains the other (see also Radkevich 2010; Zompì 2017). We return to this point below in Sect. 3.5.

See also Harðarson (2016) for evidence that the position of the genitive relative to the dative is not universally stable on Caha’s hierarchy. We include genitive and possessive forms in the data in the online appendix.

The online supplemental material includes the data from all 89 languages with a three-way contrast, since some patterns we exclude as non-suppletive are nevertheless irregular in one way or another, and thus relevant to our interests if other criteria for defining suppletion are used.

Data from Acharya (1991:107) and from Sushma Pokharel, personal communication. L and M refer to low and mid honorific grades of the second person.

This is of course the same issue that arises with the treatment of “irregularity” more broadly, as famously in the venerable English past tense debate. Our sense of suppletion is narrow, cf. Corbett’s (2007) “maximally irregular” phonology.

Although regularised to AAA in, for example, Nepali, as shown above.

Above, we have been representing case containment in terms of [ [ [ unmarked ] dependent ] oblique ]. Since Icelandic has a nominative–accusative case alignment, the case structure for Icelandic is [ [ [ nominative ] accusative ] dative ].

David Adger, Andrea Calabrese, and others have raised the question of whether one could treat the nominative as the marked form, and the non-nominative as the elsewhere case, thus accounting for its wider distribution. This depends on the representation of the unmarked case, e.g., whether the nominative is the absence of case, and thus the larger question of whether rules of suppletion may make reference to the absence of features. For degree morphology, the positive form of the adjective is typically the base for derivational morphology, hence that allomorph should be treated as context-free; but because pronouns do not typically participate in morphological derivation, an analogous argument is hard to construct. We maintain here that the featurally unmarked exponent should be the default, and return to the role of markedness in Sect. 4.3.3.

The Andi form is an ABB pattern: emi-/ƚƚe is the wh-root; -Ril is a suffix that distinguishes, according to the description, ‘known’ from ‘unknown’ wh-words.

The Albanian third person singular pronoun may also be an ABC pattern but is less clear; see fn. 96 below.

Radkevich’s structure is more articulated than the one given here. In addition, she argues that patterns of portmanteau morphology suggest that place and path (and their dependents) form a (surface) constituent, to the exclusion of the dependent case node. See Pantcheva (2011) for an approach which posits a total order among the local cases.

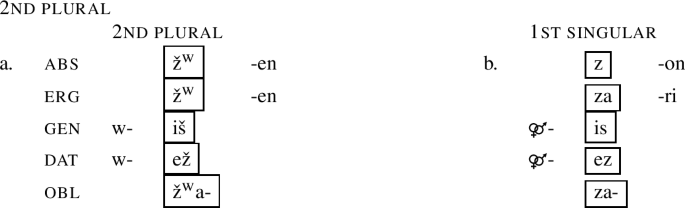

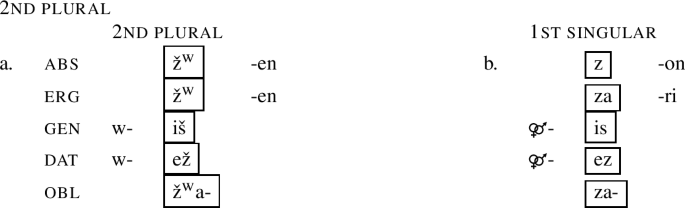

Even if we set aside the possibility of a partial, rather than a total, order among the oblique cases, it may be possible to analyse the final z in the dative as constituting the same formative as the initial z\(^{\text{w}}\)- in the other forms, and thus an AAA pattern. Nina Radkevich calls our attention to Alekseev (1985:70–75), who analyses both the genitive and dative as arising (historically) from metathesis of z and w, plus a vowel change, and finds evidence for the components of this analysis in related languages. This analysis may be supported by analogy to the Archi 1sg forms, which show a similar pattern, including devoicing in the genitive (1b) (see Moskal 2013; Alekseev 1985):

- (i)

- (i)

By contrast, the comitative pattern would not be problematic even if the comitative were to turn out to be best analysed as a postposition: as long as the comitative selects an ergative complement, it is the ergative that is triggering the relevant suppletion.

Our study encompasses primarily personal pronouns, although other pronoun types (demonstrative, interrogative, etc.) should, all else being equal, show analogous patterns. A potential ABA counter-example comes from Khakas demonstratives (Brown et al. 2003; Baskakov 1975) called to our attention by Stanislao Zompì, though as Zompì notes, it is only problematic if one accepts that there a single, suppletive, demonstrative paradigm, as opposed to two defective series of demonstratives, with overlapping, but slightly different, meaning, cf., perhaps, Baskakov (1975:151).

AAB is also found in our number survey, and is frequently attested in suppletion for clusivity, see Moskal (to appear).

Nakh-Daghestanian is a rich source for suppletion. In addition to the A(A)B and AAB patterns discussed, one also finds ABB patterns in among the 2sg pronouns, as in Avar: abs: mun, erg: du-la, dat: du-r.

(20) represents one possible way of expressing the interaction of number and case in Wardaman, where the non-singular marker -bulu is absent in the plural dative. As in any non-transparent containment structure, an additional mechanism is needed to ensure that the ergative exponent -yi/-ji is not overtly expressed in the dative. Theories invoking containment have ready means to express this.

This is consistent with Greenberg’s Universal 39: “Where morphemes of both number and case are present and both follow or both precede the noun base, the expression of number almost always comes between the noun base and the expression of case.”

The relevance of these forms was originally pointed out by an anonymous reviewer of Bobaljik (2012). Andrea Calabrese, in a work in progress, offers an alternative characterisation in which on-, respectively, en- are the underlying forms of the pronominal bases and in which no suppletion is involved. Rather, the nominative forms involve an augmentation of the base (compare our treatment of Archi, above), mirroring in some ways the historical development of the irregular nominatives for the first person, at least (Andronov 2003:156–163).

Not all cases are shown here. The genitive/oblique is zero-marked, and thus may give the impression that the dative (and other postpositional cases such as the locative, not shown) are built from the genitive/oblique. We take no stand on whether the dative is built from the genitive (since we have remained agnostic about the position of genitive in a case hierarchy) or whether all the obliques abstractly contain the accusative, with a zero marker in the genitive making it look “smaller.” Our discussion here focuses on the relation between case and number.

Our conclusions from the Chuvash versus Evenki contrast are tentative, not least because (i) the alternation p/b∼m could be morphophonological, rather than suppletive, and (ii) whether the plural u intervenes between the root and the case marker in Evenki depends on how one segments the plural pronominal base. If the pronouns are segmented as b-i, m-i-ne, s-u, s-i-ne etc., recognising distinct person and number morphemes, then the b-∼m- alternation has a non-adjacent trigger (case). Alternatively, one could posit an ablaut rule, changing i to u without decomposing the pronominal bases into person and number, which would leave the case-driven alternation as applying to structurally adjacent morphemes.

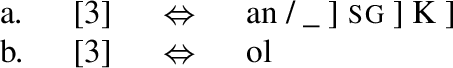

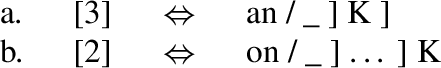

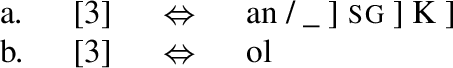

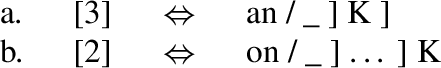

The apparent ‘blocking’ effect seen in Khakas is not a locality effect under this approach and must be stated in the vocabulary insertion rules of that language. Moskal and Smith (2016) propose that it is the non-nominative singular forms that are suppletive, and are picked out by VI-rule in (ia) that makes reference to both number and case. All other forms (nominative singular and all plural forms) use the elsewhere form of the base, determined by the elsewhere rule in (ib):

- (i)

Alternatively, one may simply state in the rule itself that the Khakas non-nominative form requires adjacency to K (as in (iia)) as opposed to the Tamil oblique allomorph, which requires only (domain-local) c-command, but not adjacency (iib). If singular number is pruned or otherwise not present in the structure at the point of vocabulary insertion, the rules in (ii) will distinguish the two types of system.

- (ii)

Since the blocking effects are not immediately relevant to our purposes, we refer the reader to Moskal and Smith (2016) for further discussion.

- (i)

It should be noted that adopting this view of case containment may yet turn out to be inconsistent with the view of locality advocated for in Moskal (2015a). There, she argues that a small number of instances of case suppletion in lexical nouns results from the absence of a number node, which brings case into the Accessibility Domain of the root. However, adopting the structural containment of case means that in the ‘one-node-above-cyclic-nodes’ approach that Moskal gives, case suppletion in lexical nouns is unable to be stated, since the only node able to be targeted would be K1, and hence there would be no way to distinguish K1 from K2. A similar set of questions is raised if NumberP is split, as we suggest below, or if there are other functional elements in the nominal spine.

In fact the opposite is also attested, with the plural apparently containing the dual. For expository reasons, we hold that in abeyance for the moment, returning to such evidence in Sect. 4.3.

According to McGregor, the inclusive does not have a specific unit-augmented form.

See Daniel (2005) for an overview of plural marking in independent pronouns. In Daniel’s survey of 261 languages, almost 3/4 show suppletion for number, either with (69) or without (114) an independent plural affix. Daniel does not include duals, and so is not informative for the current study.

We also note that Mapuche builds the plural from the dual, not vice versa.

Third person the is also a demonstrative, but has a different plural and dual as demonstrative than as pronoun.

Thanks to Kenyon Branan for pointing these out to us.

The neutralisation of a 2 vs. 3 person contrast in the plural suggests that only one of these is properly considered an ABC pattern.

Sources: Wambaya (Nordlinger 1998), Yagua, (Payne and Payne 1990), Dehu (Smith 2011). Smith draws on an old source, and may give an incomplete paradigm. The description in Lenormand (1999:24–27) decomposes the pronouns into an honorific prefix, a person root, and a number suffix, and presents a more regular picture, with ABB in the first person, but regular AAA person formatives in the second and third persons.

There is no dual in third person.

See Terrill (1998:23–25) for further discussion of the Biri forms. Terrill suggests an etymology for dual yibala that involves “the /u/ being fronted to /i/ after the /y/” (p. 25). She suggests also that the alternative second person plural yubala is a recent addition to the language. Note that -bala is not a regular number affix in the language.

We will assume that the explanation give for Wajarri is the same for Nyamal.

The reason for why the order of the columns has been switched to singular–dual–plural will become apparent shortly.

Examples are presented with Harbour’s segmentation and analysis.

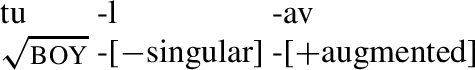

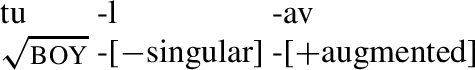

In Lavukaleve, it appears that there is language-internal variation on this point. In pronouns, descriptively, dual forms are built from plurals. Nouns generally do not show overt containment, however there are some irregular nouns that in the plural end in lav (our example above is one of these). It is possible here potentially to decompose the ‘plural’ suffix into l+av. l is a frequent dual marker in the language, and av is a marker of plurality as well, in some words, which is a variant of a general [Vv] morpheme for plurality. In this instance, in terms of the analysis of number to be adopted below, it is possible to view l as the spell-out of [−singular], and av as the spell-out of [+augmented]. Tulav, our example listed in Table 50, would then have the decomposition as follows:

- (i)

On this analysis, the plural is built on top of the dual for nouns of this type (at least: the only overt morphological evidence we have is for a noun vs. pronoun contrast), and the triple would constitute an AAB pattern, rather than ABA.

- (i)

This is a simplification of Harbour’s conclusions, which are broader than applying only to languages which make a distinction between singular, plural and dual.

An alternative to [±augmented] is its inverse: [±minimal]. Harbour (2014) settles on [±augmented] since recursion of this feature allows him to capture richer number distinctions including paucals, see Harbour (2014) for other number systems. Depending on the combination of the features, we make further predictions about suppletive patterns where the features stand in containment relations.

Note that the fourth combination [+singular, +augmented] is semantically incoherent; [−augmented] is therefore redundant in the context of [+singular].

Harbour’s (2008) analysis of adjectival suppletion in Kiowa seemingly requires that [±singular] and [±augmented] be on the same head, Number\(^{\text{0}}\). However, that argument relies on the assumption that the trigger for suppletion must be strictly adjacent (structurally and linearly) to the target, an assumption that we have argued above is unsupportable. Note that having both features on a single head also requires a less transparent mapping from syntax to affix order, when both [±singular] and [±augmented] have discrete exponents, as in Manam. For whatever it is worth, our proposal will allow a 1:1 mapping from syntactic heads to overt affixes, respecting some version of the mirror principle (Baker 1985). In more recent work, Harbour does distribute the features across nodes, for example, in the analysis of constructed duals in Harbour (2017).

It should be borne in mind that we are not making the claim that this is the universal structure of NumP. Harbour (2014) shows that there are languages that do not make use of the feature [±singular], and only use [±augmented] (languages which only make a minimal-augmented contrast for instance). Other features, and combinations are attested, see Harbour (2014) for discussion.

Moskal (to appear) notes that within the realm of clusivity there is variation as to whether the inclusive or the exclusive serves as the base for the other. That is, in some languages, the inclusive form seems to contain the exclusive form, whereas in others, the exclusive form contains the inclusive form. This is the same situation that we note for the containment of dual and plural above. However, Moskal (to appear) shows that there is this time no evidence that suppletion also varies along these lines. That is, although containment relations at times suggest the triple singular–inclusive–exclusive, suppletion patterns never follow this triple. This difference to number goes beyond the scope of our paper, and we refer the reader to Moskal (to appear) for further discussion.

We omit the [±augmented] node in the singular, as the value is redundant, but adding it in (36a) would not affect the point here.

That [+sg] is unmarked, relative to [−sg] in the sense used here is well established: if one value of number is systematically null, with the other value(s) bearing an overt mark, then it is singular which is systematically null (Corbett 2000). We put aside the interesting question here of the relation of morphological markedness to semantic markedness (on which see Bobaljik et al. 2011).

As a reviewer and others note, one could ask about German m-ich whether an alternative segmentation should be considered, in light of nominative ich, which would take the m- to be an accusative prefix, unique to the first person singular. While acknowledging that the personal pronoun paradigm is a small, closed class, and that the child acquiring German might consider various possible segmentations, there are more parallels speaking in favour of the analysis we have given. Along with the general observation that German nominal inflection is uniquely suffixing, all of the following pairwise proportional analogies support this analysis, where there is no proportional analogy that can be made in the language to support a putative m- accusative prefix: mich:dich::mir:dir, mich:mir::dich:dir, mich:mein::dich:dein, mich:mein::sich:sein (and so on for inflected forms of the possessive). We assume that some such tallying goes into the weighting of the likelihood of different competing segmentations.

We thank Martin Haspelmath, in comments on an earlier draft, for pressing us to be clear about this important issue.

See Sect. 3.5.

Some subject pronouns in Basaa are suppletive with respect to the ‘independent’ series, which occurs in all other positions, but it is not clear that this is a case-driven alternation, and in any event, Hyman does not provide evidence for a distinction analysable as more than a two-way distinction in case.

There is evidently a third person pronominal formative a-, alternating with demonstrative k(ë)-. While the person formative is thus invariant (AAA), the marking of masculine (contrasting with feminine) shows an ABB pattern in the singular (-i, -të, -tij), compared to an AAA pattern in the plural.

We tentatively treat this as synchronically suppletive, although historically, they may share a stem.

Note also corresponding feminine forms: sɔ–tami–təmis–etc. Since gender distinctions are lost in the dative and ablative, the feminine forms have not been counted as distinct from the ABB pattern in the masculine series.

Despite the -n- in all three cases, we treat the on∼nj(e)- alternation as suppletive, as the initial n- in the non-nominatives, which occurs only after prepositions in most Slavic languages, does not come from the same source as the -n in the nominative (Hill 1977). This suppletive root is shared by all third person pronouns, to which morphology indicating number, gender, and case is added. We list the feminine and plural forms separately below, but as they share a base, they are not truly independent datapoints for suppletion. See also the discussion of Polish in the main text.

As in Slavic, the suppletive third person pronominal base is shared across distinct number and gender forms.

If the masculine singular is treated as ABB as in fn. 76, then the feminine would appear to be ABC (-jo, -të, -saj) once the pronominal formative a- is factored out.

See also fn. 93.

Initial nga- also occurs in the second person so cannot be treated as the unique formative for 1sg, suggesting an AAB analysis. Alternatively, it may be AAA with some irregularity.

McGregor (1990:170) notes that the oblique stem nhoowoo corresponds only to the 3sg pronoun, and not to the homophonous determiner niyi ‘that’, consistent with analysing this as a suppletive alternation for the pronoun.

Initial nga- also occurs in the second and third person singular accusatives, so cannot be treated as the unique formative for 1sg, suggesting an AAB analysis. Alternatively, it may be AAA with some irregularity. Apparently cognate forms occur in Wambaya, but see fn. 74.

Cognate: Wambaya.

The alternation ña-, ña-, ŋaŋ- is similar to that in neighbouring Jingulu, although these languages are not described as related in, for example, Pensalfini (2001).

This pronoun marks masculine class as opposed to male, and is used only by female speakers (Kirton 1996:12). The order of the cases presents a possible challenge to Caha’s hierarchy; see note in supplemental online materials.

Initial ŋa- is common to all first persons across three numbers. The dual and plural pronouns are readily segmented, but the first singular stem is not.

Also Jehai.

Cognates: Ambai, Boumaa Fijian, Hawaiian, Manam, Maori, Mokilese, Paamese, Pileni, Rapa Nui, Rotuman, Samoan, Santali, Sursurunga, Tangga, Tiri, Tokelauan, Toqabaqita, Tuvaluan, Warembori.

Cognates: Boumaa Fijian, Hawaiian, Manam, Maori, Mokilese, Pileni, Rapa Nui, Rotuman, Samoan, Sursurunga, Tangga, Tiri, Toqabaqita, Tuvaluan, Warembori.

Cognates: Ambai, Boumaa Fijian, Ngaju, Sursurunga, Tangga, Dehu, Toqabaqita, Warembori.

Cognates: Ambai, Boumaa Fijian, Hawaiian, Manam, Maori, Mokilese, Ngaju, Pileni, Rotuman, Samoan, Sursurunga, Tangga, Tokelauan, Toqabaqita, Tuvaluan, Warembori.

Cognate: Jingulu.

Cognates: Ngaju, Santali.

Cognate: Tiri.

This is an ABBC pattern. Dual has been excluded from the table. The triple is singular–plural–paucal.

Cognate: Jingulu.

Cognates: Flinders Island, Jarnango, Kuku-Yalanji, Nyawaygi, Wajarri, Wikngenchera.

References

Acharya, Jayaraj. 1991. A descriptive grammar of Nepali and an analyzed corpus. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Adger, David, Susana Bejar, and Daniel Harbour. 2003. Directionality of allomorphy: A reply to Carstairs–McCarthy. Transactions of the Philological Society 101 (1): 109–115.

Alekseev, M. E. 1985. Voprosy sravnitel’no-istoričeskoj grammatiki lezginskix jazykov. Moscow: Nauka.

Allan, Robin, Philip Holmes, and Tom Lundskær-Nielsen. 1995. Danish: A comprehensive grammar. London: Routledge.

Andronov, Mikhail S. 1980. The Brahui language. Moscow: Nauka.

Andronov, Mikhail S. 2003. A comparative grammar of the Dravidian languages. München: Lincom Europa.

Arensen, Jonathan E. 1982. Murle grammar. Occasional papers in the study of Sudanese languages. Juba: Summer Institute of Linguistics and University of Juba.

Armbruster, Charles Herbert. 1960. Dongolese Nubian: A grammar. Cambridge: University Press.

Asher, Ronald E. 1982. Tamil. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Asher, Ronald E., and T. C. Kumari. 1997. Malayalam. Descriptive grammars series. London: Routledge.

Baerman, Matthew. 2014. Suppletive kin terms paradigms in the languages of New Guinea. Linguistic Typology 18 (3): 413–448.

Baird, Louise. 2008. A grammar of Klon: A non-Austronesian language of Alor. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Baker, Mark. 1985. The mirror principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16 (3): 373–415.

Bal, Bal Krishna. 2007. Structure of Nepali grammar. In PAN localization working papers 2004–2007. Lahore: Center for Research in Urdu Language Processing, National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences.

Barbiers, Sjef. 2007. Indefinite numerals one and many and the cause of ordinal suppletion. Lingua 117: 859–880.

Baskakov, N. A., ed. 1975. Grammatika xakasskogo jazyka. Moscow: Nauka.

Bauer, Winifred. 1993. Maori. London: Routledge.

Beaton, A. C. 1968. A grammar of the Fur language. Khartoum: Sudan Research Unit, University of Khartoum.

Bender, M. Lionel. 1996. Kunama. München: Lincom Europa.

Berger, Hermann. 1998. Die Burushaski-Sprache von Hunza und Nager. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Bergsland, Knut. 1997. Aleut grammar. Fairbanks: University of Alaska, Alaska Native Language Center.

Bhat, D. N. S., and M. S. Ningomba. 1997. Manipuri grammar. München: Lincom Europa.

Birk, D.B.W. 1976. The Malakmalak language, Daly River (Western Arnhem Land). Canberra: Australian National University.

Blake, Barry J. 1979. Pitta-Pitta. In Handbook of Australian languages, eds. Robert. M. W. Dixon and Barry J. Blake, Vol. 1, 182–242. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Blake, Barry J. 1994. Case. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan D. 2000. The ins and outs of contextual allomorphy. University of Maryland Working Papers in Linguistics 10: 35–71.

Bobaljik, Jonathan D. 2012. Universals in comparative morphology. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan D., and Heidi Harley. 2017. Suppletion is local: Evidence from Hiaki. In The structure of words at the interfaces, eds. Heather Newell, Máire Noonan, Glyne Piggott, and Lisa Travis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan David, and Uli Sauerland. 2018. *ABA and the combinatorics of morphological rules. Glossa 3 (1): 15.

Bobaljik, Jonathan D., and Susi Wurmbrand. 2005. The domain of agreement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 23 (4): 809–865.

Bobaljik, Jonathan D., and Susanne Wurmbrand. 2013. Suspension across domains. In Distributed Morphology today: Morphemes for Morris. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan D., Andrew Nevins, and Uli Sauerland. 2011. Preface: On the morphosemantics of agreement features. Morphology 21 (2): 131–140.

Bodomo, Adams. 1997. The structure of Dagaare. Stanford: CSLI.

Bonvillain, Nancy. 1973. A grammar of Akwesasne Mohawk. Gatineau: National Museum of Man.

Boretzky, Norbert. 1994. Romani: Grammatik des Kalderaš-Dialekts mit Texten und Glossar. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz Verlag.

Bowe, Heather. 1990. Categories, constituents, and constituent order in Pitjantjatjara, an Aboriginal language of Australia. London: Routledge.

Bradley, John, and Jean Kirton. 1992. Yanyuwa Wuka: A language from Yanyuwa country. Ms., University of Queensland.

Breeze, Mary J. 1990. A sketch of the phonology and grammar of Gimira (Benchnon). London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Broadbent, Sylvia M. 1964. The southern Sierra Miwok language. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bromley, H. Myron. 1981. A grammar of Lower Grand Valley Dani. Canberra: Australian National University.

Brooks, Maria Z. 1975. Polish reference grammar. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Brown, Dunstan, Marina Chumakina, Greville Corbett, and Andrew Hippisley. 2003. The Surrey Suppletion Database. University of Surrey. http://dx.doi.org/10.15126/SMG.12/1.

Browne, Wayles, and Theresa Alt. 2004. A handbook of Bosnian, Serbian, and Croatian. Durham: Slavic and East European Language Research Center (SEELRC), Duke University.

Bruce, Les. 1984. The Alamblak language of Papua New Guinea (East Sepik). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Burling, Robbins. 1961. A Garo grammar. Pune: Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute.

Bybee, Joan L. 1985. Morphology: A study of the relation between meaning and form. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bye, Patrik. 2007. Allomorphy: Selection, not optimization. In Freedom of analysis?, eds. Sylvia Blaho, Patrik Bye, and Martin Krämer, 63–92. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Caha, Pavel. 2009. The nanosyntax of case. PhD diss., University of Tromsø.

Calabrese, Andrea. 2005. Markedness and economy in a derivational model of phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Calabrese, Andrea. 2008. On absolute and contextual syncretism: Remarks on the structure of case paradigms and how to derive them. In Inflectional identity, eds. Asaf Bachrach and Andrew Nevins. Oxford studies in theoretical linguistics, 156–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, George L. 2000. Compendium of the world’s languages, Vol. 2: Ladakhi to Zuni. London: Routledge.

Carlson, Robert. 1994. A grammar of Supyire. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Chapman, Shirley, and Desmond Derbyshire. 1991. Paumarí. In Handbook of Amazonian languages, eds. Desmond C. Derbyshire and Geoffrey K. Pullum, Vol. 3, 161–352. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Charney, Jean Ormsbee. 1993. A grammar of Comanche. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Chirikba, Viacheslav. 2003. Abkhaz. München: Lincom Europa.

Clark, Larry. 1998. Chuvash. In The Turkic languages, eds. Lars Johansen and Eva A. Csató, 434–452. London: Routledge.

Cole, Peter. 1982. Imbabura Quechua. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Corbett, Greville. 2000. Number. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Corbett, Greville. 2005. Suppletion in personal pronouns: Theory versus practice, and the place of reproducibility in typology. Linguistic Typology 9: 1–23.

Corbett, Greville. 2007. Canonical typology, suppletion and possible words. Language 83 (1): 8–42.

Coupe, Alexander Robertson. 2007. A grammar of Mongsen Ao. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Courtz, Henk. 2008. A Carib grammar and dictionary. Toronto: Magoria Books.

Crowley, Terry. 1982. The Paamese language of Vanuatu. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Curnow, Timothy J. 1997. A grammar of Awa Pit (Cuaiquer): An indigenous language of south-western Colombia. PhD diss., Australian National University.

Cyffer, Norbert. 1998. A sketch of Kanuri. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

Daniel, Michael. 2005. Plurality in independent personal pronouns. In The world atlas of language structures, eds. Martin Haspelmath, Matthew S. Dryer, David Gil, and Bernard Comrie. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Rijk, Rudolf P. G. 2007. Standard Basque: A progressive grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dench, Alan Charles. 1995. Martuthunira: A language of the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Canberra: Australian National University.

Dimmendaal, Gerrit Jan. 1982. The Turkana language. Leiden: Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1972. The Dyirbal language of North Queensland. Cambridge studies in linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1988. A grammar of Boumaa Fijian. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1989. Australian languages: Their nature and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dixon, R. M. W. 2010. A grammar of Yidiɲ. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dol, Philomena. 2007. A grammar of Maybrat. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Donaldson, Tamsin. 1980. Ngiyambaa: The language of the Wangaaybuwan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donaldson, Bruce C. 1993. A grammar of Afrikaans. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Donohue, Mark, and Lila San Roque. 2004. I’saka. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Douglas, Wilfred H. 1981. Watjarri. In Handbook of Australian languages, eds. R. M. W. Dixon and Barry J. Blake, Vol. 2. Canberra: Australian National University.

Duff-Tripp, Martha. 1997. Gramática del idioma yanesha’ (amuesha). Lima: Ministerio de Educación, Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

Ebert, Karen Heide. 1979. Sprache und Tradition der Kera (Tschad), Vol. 3: Grammatik. Berlin: Reimer.

Einarsson, Stefán. 1945. Icelandic. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Embick, David. 2010. Localism versus globalism in morphology and phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Embick, David, and Alec Marantz. 2008. Architecture and blocking. Linguistic Inquiry 39 (1): 1–53.

Erschler, David. 2017. On multiple exponence, feature stacking, and locality in morphology. Ms., University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Evans, Nicholas D. 1995. A grammar of Kayardild. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Evans, Nicholas. 2015. Inflection in Nen. In The Oxford handbook of inflection, ed. Matthew Baerman, 545–575. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Everett, Daniel L. 1986. Pirahã. In Handbook of Amazonian languages 1, eds. Desmond C. Derbyshire and Geoffrey K. Pullum, 200–325. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Fedden, Olcher Sebastian. 2007. A grammar of Mian. PhD diss., University of Melbourne.

Ferrar, H. 1972. A French reference grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Foley, William A. 1991. The Yimas language of Papua New Guinea. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Forchheimer, Paul. 1953. The category of person in language. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Fortescue, Michael. 1984. West Greenlandic. London: Croom Helm.

Frajzyngier, Zygmunt. 2001. A grammar of Lele. Stanford: CSLI.

Frajzyngier, Zygmunt, Eric Johnston, and Adrian Edwards. 2005. A grammar of Mina. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Frank, Paul. 1990. Ika syntax. Arlington: Summer Institute of Linguistics and The University of Texas at Arlington.

Franklin, Karl James. 1971. A grammar of Kewa, New Guinea. Canberra: Australian National University.

Furby, Edward S., and Christine E. Furby. 1977. A preliminary analysis of Garawa phrases and clauses. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Gair, James W., and John C. Paolillo. 1997. Sinhala. München: Lincom Europa.

Genetti, Carol. 2007. A grammar of Dolakha Newar. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Gordon, Lynn. 1986. Maricopa morphology and syntax. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Graczyk, Randolph. 2007. A grammar of Crow. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1963. Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements. In Universals of language, ed. Joseph H. Greenberg, 73–113. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gregores, Emma, and Jorge Alberto Suárez. 1967. A description of colloquial Guaraní. The Hague: Mouton and Company.

Grune, Dick. 1998. Burushaski: An extraordinary language in the Karakoram Mountains. Pontypridd: Joseph Biddulph.

Guillaume, Antoine. 2008. A grammar of Cavineña. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Guirardello, Raquel. 1999. A reference grammar of Trumai. Houston: Rice University Press.

Haas, Mary R. 1940. Tunica. New York: J. J. Augustin.

Haiman, John. 1980. Hua: A Papuan language of the Eastern Highlands of New Guinea. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20, eds. Ken Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harðarson, Gísli Rúnar. 2016. A case for a weak case contiguity hypothesis: A reply to Caha. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34 (4): 1329–1343.

Harbour, Daniel. 2008. Morphosemantic number: From Kiowa noun classes to UG number features. New York: Springer.

Harbour, Daniel. 2011. Valence and atomic number. Linguistic Inquiry 42 (4): 561–594.

Harbour, Daniel. 2014. Paucity, abundance, and the theory of number. Language 90 (1): 185–229.

Harbour, Daniel. 2017. Frankenduals: Their typology, structure, and significance. Ms., Queen Mary University of London.

Harms, Philip Lee. 1994. Epena Pedee syntax. Dallas/Arlington: Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas.

Haspelmath, Matin. 1993. A grammar of Lezgian. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Haugen, Jason D., and Daniel Siddiqi. 2013. Roots and the derivation. Linguistic Inquiry 44 (3): 493–517.

Heath, Jeffrey. 1984. A functional grammar of Nunggubuyu. Atlantic Highlands/Canberra: Humanities Press/Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Heath, Jeffrey. 1999. A grammar of Koyraboro (Koroboro) Senni: The songhay of Gao, Mali. Köln: R. Köppe.

Heath, Jeffrey. 2005. A grammar of Tamashek. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Heath, Jeffrey. 2008. A grammar of Koyra Chiini: The songhay of Timbuktu. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Hercus, Luise. 1982. The Bāgandji language. Vol. 67 of Pacific linguistics. Canberra: Australian National University.

Hewitt, B. G. 1995. Georgian: A structural reference grammar. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hill, Steven P. 1977. The n-factor and Russian prepositions. The Hague: Mouton.

Holton, David, Peter Mackridge, and Irene Philippaki-Warburton. 1997. Greek: A comprehensive grammar of the modern language. London: Routledge.

Hyman, Larry. 2003. Basaa (A.43). In The Bantu languages, eds. Derek Nurse and Gérard Philippson, 257–282. London: Routledge.

Ibragimov, Garun. 1978. Rutul’skij jazyk [Rutul]. Moscow: Nauka.

Isaac, Kendall Mark. 2007. Participant reference in Tunen narrative discourse. MA thesis, Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics.

Iwasaki, Shoichi, and Preeya Ingkaphirom. 2005. A reference grammar of Thai. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobson, Steven A. 1995. A practical grammar of the Central Alaskan Yup’ik Eskimo language. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center.

Jakobson, Roman. 1936/1971. Beitrag zur allgemeinen Kasuslehre. Gesamtbedeutungen der russischen Kasus. In Selected writings, Vol. 2, 23–71. The Hague: Mouton.

Joseph, Umbavu Varghese. 2007. Rabha. Leiden: Brill.

Kaiser, Stefan, Yasuko Ichikawa, Noriko Kobayashi, and Hilofumi Yamamoto. 2001. Japanese: A comprehensive grammar. London / New York: Routledge.

Karlsson, Fred. 1999. Finnish: An essential grammar. London: Routledge.

Katz, Joshua. 1998. Topics in Indo-European personal pronouns. PhD diss., Harvard University.

Kayne, Richard. 2005. Movement and silence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kenesei, István, Robert M. Vago, and Anna Fenyvesi. 1998. Hungarian. London: Routledge.

Key, Harold H. 1967. Morphology of Cayuvava. The Hague: Mouton.

Kibrik, Aleksandr E., and Sandro V. Kodzasov. 1990. Sopostavitel’noe izučenie dagestanskix jazykov. Imja. Fonetika. Moscow: Moscow University Press.

Kilian-Hatz, Christa. 2008. A grammar of Modern Khwe (Central Khosian). Köln: R. Köppe.

Kimball, Geoffrey. 1991. Koasati grammar. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1973. “Elsewhere” in phonology. In A Festschrift for Morris Halle, 93–106. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

Kirton, Jean F. 1996. Further aspects of the grammar of Yanyuwa. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1997. Turkish. London: Routledge.

Koshal, Sanyukta. 1979. Ladakhi grammar. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidasa.

Kozintseva, Natalia A. 1995. Modern Eastern Armenian. München: Lincom Europa.

Kratochvil, Frantisek. 2007. A grammar of Abui. Utrecht: LOT Dissertations in Linguistics.

Kruspe, Nicole. 1999. A grammar of Semelai. PhD diss., University of Melbourne.

Kumar, Pramod. 2012. Descriptive and typological study of Jarawa. PhD diss., Jawaharlal Nehru University.

LaPolla, Randy J., and Chenglong Huang. 2003. A grammar of Qiang. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lee, Iksop, and Robert Ramsey. 2000. The Korean language. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Lenormand, Maurice-Henry. 1999. Dictionnaire drehu–français: La langue de Lifou, Iles Loyalty. Nouméa: Le Rocher-à-la-voile.

Lichtenberk, Frantisek. 1983. A grammar of Manam. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Lichtenberk, František. 2008. A grammar of Toqabaqita. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Macauley, Monica. 1996. A grammar of Chalcatongo Mixtec. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Marantz, Alec. 2000. Words. Ms., MIT.

Marantz, Alec. 2007. Phases and words. In Phases in the theory of grammar, ed. Sook-Hee Choe, 199–222. Seoul: Dong In.

Maslova, Elena. 2003. A grammar of Kolyma Yukaghir. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Mathiassen, Terie. 1996. A short grammar of Lithuanian. Columbus: Slavica Publishers.

McCreight, Katherine, and Catherine V. Chvany. 1991. Geometric representation of paradigms in a modular theory of grammar. In Paradigms: The economy of inflection, ed. Frans Plank, 91–112. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

McFadden, Thomas. 2014. Why nominative is special: Stem-allomorphy and case structures. Talk given at GLOW 37, Brussels.

McFadden, Thomas. 2018. *aba in stem-allomorphy and the emptiness of the nominative. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3 (1): 1–36.

McGregor, William. 1990. A functional grammar of Gooniyandi. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

McGregor, William. 1994. Warrwa. Vol. 89 of Languages of the world/materials. München: Lincom Europa.

McLendon, Sally. 1975. A grammar of Eastern Pomo. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mel’čuk, Igor A. 1994. Suppletion: Toward a logical analysis of the concept. Studies in Languages 18 (2): 339–410.

Merchant, Jason. 2015. How much context is enough? Two cases of span-conditioned stem allomorphy. Linguistic Inquiry 46 (2): 273–303.

Merlan, Francesca C. 1982. Mangarayi. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Merlan, Francesca C. 1994. A grammar of Wardaman, a language of the Northern Territory of Australia. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Mosel, Ulrike, and Even Hovdhaugen. 1992. Samoan reference grammar. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

Moshinsky, Julius. 1974. A grammar of Southeastern Pomo. Berkeley: University of California Publications in Linguistics.

Moskal, Beata. 2013. On some suppletion patterns in nouns and pronouns. Talk given at PhonoLAM, Meertens Instituut.

Moskal, Beata. 2014. The role of morphological markedness in exclusive/inclusive pronouns. In Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 40, 354–368.

Moskal, Beata. 2015a. Domains on the border: Between morphology and phonology. PhD diss., University of Connecticut Storrs.

Moskal, Beata. 2015b. Limits on allomorphy: A case-study in nominal suppletion. Linguistic Inquiry 46 (2): 363–375.

Moskal, Beata. to appear. Excluding exclusively the exclusive: Suppletion patterns in clusivity. Glossa.

Moskal, Beata, and Peter W. Smith. 2016. Towards a theory without adjacency: Hyper-contextual VI-rules. Morphology 26 (3–4): 295–312.

Mous, Maarten. 1993. A grammar of Iraqw. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Müller, Gereon. 2004. On decomposing inflection class feature: Syncretism in Russian noun inflection. In Explorations in nominal inflection, eds. Gereon Müller, Lutz Gunkel, and Gisela Zifonum, 189–227. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Murane, Elizabeth. 1974. Daga grammar: From morpheme to discourse. Vol. 43 of Summer institute of linguistics publications in linguistics and related fields. Norman: Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of Oklahoma.

Naish, Constance. 1979. A syntactic study of Tlingit. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Nedjalkov, Igor. 1997. Evenki. London: Routledge.

Nekes, Hermann, and Ernest Worms. 2006. Australian languages. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Nevins, Andrew. 2010. Locality in vowel harmony. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Marked targets versus marked triggers and impoverishment of the dual. Linguistic Inquiry 42 (3): 413–444.

Newman, Stanley. 1944. The Yokuts language of California. New York: The Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology.

Newmark, Leonhard. 1982. Standard Albanian: A reference grammar for students. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Nichols, Johanna. 2011. Ingush grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nickel, Klaus Peter. 1994. Samisk grammatikk. Karasjok: Girji.

Nikolaeva, Irina. 1999. Ostyak. München: Lincom Europa.

Nikolaeva, Irina, and Maria Tolskaya. 2001. A grammar of Udihe. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Noonan, Michael. 1992. A grammar of Lango. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Nordbustad, Frøydis. 1988. Iraqw grammar: An analytical study of the Iraqw language. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

Nordlinger, Rachel. 1998. A grammar of Wambaya, Northern Territory (Australia). Canberra: Australian National University.

Noyer, Rolf. 1992. Features, positions and affixes in autonomous morphological strcuture. PhD diss., MIT.

Oates, William J., and Lynette F. Oates. 1968. Kapau pedagogical grammar. Canberra: Australian National University.

Obata, Kazuko. 2003. A grammar of Bilua. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Okell, John. 1969. A reference grammar of colloquial Burmese (two volumes). London: Oxford University Press.

Olawsky, Knut. 2006. A grammar of Urarina. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Osada, Toshiki. 1992. A reference grammar of Mundari. Tokyo: Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

Osborne, C. R. 1974. The Tiwi language. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Owens, Jonathan. 1985. A grammar of Harar Oromo (Northeastern Ethiopia). Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Palmer, Bill. 2016. The languages and linguistics of the New Guinea area: A comprehensive guide. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Pandharipande, Rajeshwari V. 1997. Marathi. London: Routledge.

Pantcheva, Marina. 2011. Decomposing path: The nanosyntax of spatial expressions. PhD diss., Universitetet i Tromsø.

Payne, Doris L., and Thomas Payne. 1990. Yagua. In Handbook of Amazonian languages 2, eds. Desmond C. Derbyshire and Geoffrey K. Pullum, 249–474. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Pensalfini, Robert J. 1997. Jingulu grammar, dictionary, and texts. PhD diss., MIT.

Pensalfini, Robert. 2001. On the typological and genetic affiliation of Jingulu. In Forty years on: Ken Hale and Australian languages, eds. Jane Simpson, David Nash, Mary Laughren, Peter Austin, and Barry Alpher, 385–399. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Pensalfini, Robert J. 2003. A grammar of Jingulu: An aboriginal language of the Northern Territory. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Penzl, Herbert. 1955. A grammar of Pashto: A descriptive study of the dialect of Kandahar. Washington: American Council of Learned Societies.

Pitman, Donald. 1980. Bosquejo de la gramática araona. Riberalta: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

Polinsky, Maria, Nina Radkevich, and Marina Chumakina. 2017. Agreement between arguments? Not really. In Verbal domain, eds. Roberta D’Alessandro, Irene Franco, and Ángel J. Gallego, 49–84. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Poppe, Nikolaus. 1951. Khalkha–Mongolische Grammatik. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag GMBH.

Poulos, George, and Christian T. Msimang. 1998. A linguistic analysis of Zulu. Cape Town: Via Afrika.

Priestly, T. 1993. Slovene. In The Slavonic languages, eds. Bernard Comrie and Greville Corbett, Vol. 1, 388–451. London: Routledge.

Quick, Phil. 2007. A grammar of the Pendau language of central Sulawesi, Indonesian. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University.

Radkevich, Nina. 2010. On location: The structure of case and adpositions. PhD diss., University of Connecticut Storrs.

Reesink, Ger P. 1987. Structures and their functions in Usan: A Papuan language of Papua New Guinea. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Reh, Mechthild. 1985. Die Krongo-Sprache (Nìinò mó-dì). Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

Reichle, Verena. 1981. Bawm language and lore: Tibeto-Burman area. Bern: Peter Lang.

Rennison, John R. 1997. Koromfe. London: Routledge.

Rich, Rolland. 1999. Diccionario arabela-castellano. Lima: Instituto Lingüístico De Verano.

Robins, R. H. 1958. The Yurok language, grammar, texts, lexicon. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Romero-Figueroa, Andrés. 1997. A reference grammar of Warao. München: Lincom Europa.

Rood, David S. 1976. Wichita grammar. New York: Garland.

Rubach, Jerzy. 1984. Cyclic and lexical phonology: The structure of Polish. Dordrecht: Foris.

Rude, Noel E. 1985. Studies in Nez Perce grammar and discourse. PhD diss., University of Oregon, Eugene.

Rumsey, A. 1982. An intra-sentence grammar of Ungarinjin, north-western Australia. Canberra: Australian National University.

Saeed, John I. 1999. Somali. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sakel, Jeanette. 2004. Mosetén. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Salminen, Tapani. 1998. Nenets. In The Uralic languages, ed. Daniel Abondolo, 516–547. London: Routledge.

Saltarelli, Mario, Miren Azkarate, David Farwell, Jon de Urbina, and Lourdes Oñederra. 1988. Basque. London: Croom Helm.

Seiler, Hansjakob. 1977. Cahuilla grammar. Banning: Malki Museum Press.

Seiler, Walter. 1985. Imonda, a Papuan language. Canberra: Australian National University.

Siddiqi, Daniel. 2009. Syntax within the word: Economy, allomorphy and argument selection in distributed morphology. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Smeets, Inke. 2008. A grammar of Mapuche. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Smith, Norval. 2011. Free personal pronoun system database. Available at http://languagelink.let.uu.nl/fpps/. Accessed 10 August 2019.

Smith, Peter W., Beata Moskal, Ting Xu, Jungmin Kang, and Jonathan D. Bobaljik. 2015. Pronominal suppletion: Case and number. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 45, eds. Thuy Bui and Deniz Özyıldız, Vol. 3, 69–78. Amherst: GLSA.

Spencer, Andrew, and Gregory T. Stump. 2013. Hungarian pronominal case and the dichotomy of form in inflectional morphology. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31: 1207–1248.

Sridhar, S. N. 1990. Kannada: Descriptive grammar. London: Routledge.

Tamura, Suzuko. 2000. The Ainu language. Tokyo: Sanseido.

Tauberschmidt, Gerhard. 1991. A grammar of Sinaugoro. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Teng, Stacy Fang-Ching. 2008. A reference grammar of Puyuma. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Terrill, Angela. 1998. Biri. München: Lincom Europa.

Terrill, Angela. 2003. A grammar of Lavukaleve. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Thomas, David. 1955. Three analyses of the Ilocano pronoun system. Word 11 (2): 204–208.

Thompson, Laurence C. 1987. A Vietnamese reference grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Thráinsson, Hoskuldur, Hjalmar P. Petersen, Jógvan Jacobsen, and Zakaris Svabo Hansen. 2004. Faroese: An overview and reference grammar. Tórshavn: Foroya Fródskaparfelag.

Tosco, Mauro. 2001. The Dhaasanac language: Grammar, texts and vocabulary of a Cushitic language of Ethiopia. Köln: Köppe.

Traill, Anthony. 1994. A !xóõ dictionary. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Trenga, Georges. 1947. Le bura-mabang du ouadaï: Notes pour servir à l’étude de la langue maba. Paris: Institut d’Ethnologie, Universitè de Paris.

Trommer, Jochen. 2008. Case suffixes, postpositions and the phonological word in Hungarian. Linguistics 46: 403–438.

Tryon, Darrell T. 1970. An introduction to Maranungku. Canberra: Australian National University.

Učida, Norihiko. 1970. Der Bengali-Dialekt von Chittagong: Grammatik, Texte, Wörterbuch. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Valentine, Randy. 2001. Nishnaabemwin reference grammar. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Valenzuela, Pilar M. 1997. Basic verbs types and argument structures in Shipibo-Conibo. Master’s thesis, University of Oregon.

van den Berg, Helma. 1995. A grammar of Hunzib. München: Lincom Europa.

van der Voort, Hein. 2004. A grammar of Kwaza. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

van Driem, George. 1992. The grammar of Dzongkha. Thimphu: Dzongkha Development Commission.

van Driem, George. 1993. A grammar of Dumi. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

van Driem, George. 1998. Languages of the Greater Himalayan region. Leiden: Brill.

Veselinova, Ljuba N. 2006. Suppletion in verb paradigms. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Viitso, Tiit-Rein. 1998. Estonian. In The Uralic languages, ed. Daniel Abondolo, 115–148. London: Routledge.

Vogt, Hans. 1940. The Kalispel language. Oslo: Norwegian Academy of Sciences / Jacob Dybwad.

Volodin, Aleksandr P. 1976. Itel’menskij jazyk. Leningrad: Nauka.

Wade, Terence L. B. 1992. A comprehensive Russian grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wali, Kashi, and Omkar N. Koul. 1997. Kashmiri: A cognitive-descriptive grammar. London: Routledge.

Waren, Olivia Ursula. 2007. Possessive pronouns in Maybrat: A Papuan language. Linguistika 14.

Watkins, Laurel J. 1984. A grammar of Kiowa. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Watters, David E. 2002. A grammar of Kham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Werner, Heinrich. 1997. Die ketische Sprache. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Westrum, Peter N. 1988. A grammatical sketch of Berik. MA Thesis, University of North Dakota.

Wilson, Darryl. 1974. Suena grammar. Workpapers in Papua New Guinea languages 8. Ukarumpa: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Winkler, Eberhard. 2001. Udmurt. München: Lincom Europa.

Zaicz, Gábor. 1998. Mordva. London: Routledge.

Zompì, Stanislao. 2017. Case decomposition meets dependent-case theories. Master’s thesis, Università de Pisa.

Acknowledgements

Portions of the work on this paper were carried out under the auspices of a Guggenheim Fellowship to Bobaljik, and with research support from the University of Connecticut, both of which are gratefully acknowledged.

We are grateful to Daniel Harbour, Martin Haspelmath and two anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier version of this paper. Questions and suggestions from audiences at various venues have helped us refine and improve the paper, including those at the LAGB, NELS 45, GLOW 48, Roots IV, SinFonIJA 9, the 2017 Debrecen Workshop in Pronouns, the Word and the Morpheme (Berlin, 2017), as well as at Bucharest, Cambridge, Concordia, Connecticut, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, Göttingen, Harvard, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft (Berlin), Leipzig, Maryland, NYU, Pennsylvania, Princeton, and Vienna. We would particularly like to acknowledge useful discussions with Andrea Calabrese, Heidi Harley, Ora Matushansky, Uli Sauerland, and Susi Wurmbrand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Appendices

Appendix A: Case

This appendix lists all the languages examined for case suppletion. For each language, we indicate in the second column (>2K) whether the language has more than two cases (apart from genitive and vocative). For these languages, we indicate whether we have identified suppletion for case, and if so in which pronouns. The online appendix provides the full dataset from all of the languages marked “Y” in the second column, i.e., as having enough case distinctions to be relevant to the study at hand.

1.1 A.1 Overview

Language | >2K | Suppletion | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

Abkhaz | N | Chirikba (2003) | |

Abui | N | Kratochvil (2007) | |

Afrikaans | N | AB | Donaldson (1980) |

Ainu | N | Tamura (2000) | |

Alamblak | Y | none | Bruce (1984) |

Albanian | Y | ABB: 1sg, 3sg.m; ABC: 3sg.f | Newmark (1982) |

Amuesha | N | Duff-Tripp (1997) | |

Arabela | N | Rich (1999) | |

Araona | N | Pitman (1980) | |

Archi | Y | AAB: 2sg, 1sg, 1plexcl, 1plincl; ?ABA: 2plFootnote 64 | |

Armenian | Y | ABB: 1sg, 2sg, 2pl | Kozintseva (1995) |

Awa Pit | Y | none | Curnow (1997) |

Basaa | N | Hyman (2003) | |

Basque | Y | ABB: 3sg.prox | Saltarelli et al. (1988) |

Bawm | N | Reichle (1981) | |

Bengali (Chittagong) | Y | none | Učida (1970) |

1.2 A.2 ABB patterns

The following table lists plausible cognate triples of pronouns showing the ABB suppletive patterns for case that we have identified. Since absolute numbers are not relevant, as opposed to the distinction between attested and unattested, we have made a number of educated guesses about cognates without making a careful study of each language. Note that only a single illustrative example of each cognate triple is given, with notes on where other languages have cognate forms given in the final column. For example, the Icelandic 1sg forms ég–mig–mér have cognates across Indo-European (Russian: ja–menja–mne; Latin ego–mē–mihi, etc.; see Table 10 in main text), but as these all descend from a common source, only one example is given in the table. Where it appears to us that a pronominal form may not be cognate with all forms in a related language (as in the Albanian nominative unë), we have listed such forms as separate entries.

We have titled the case columns as unmarked (=nominative/absolutive), marked 1 and marked 2. While the general orientation is nominative–accusative–dative or absolutive–ergative–dative, where syncretism would obscure the relevant patterns, we have made substitutions. For example, in Armenian, pronouns do not show a nominative vs. accusative distinction, hence the cases here are nominative/accusative–dative–ablative. Likewise, Albanian first and second person singular pronouns do not distinguish accusative and dative, so we have used nominative–accusative/dative–ablative. As noted in the main text, we have avoided genitive pronouns in this study as we have been unable to systematically distinguish genitive case from possessive pronouns in many of our sources.

Language | Pronoun | Cases | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Unmarked | Marked 1 | Marked 2 | |||

Indo-European: | |||||

Icelandic | 1sg | ég | mig | mér | cognates widespread in Indo-European |

Albanian | 1sg | unë | mua | meje | |

Armenian (E) | 1sg | es | inj | inj(a)nic | |

Armenian (E) | 2sg | du | k’ez | k’ez(a)nic | |

Russian | 1pl | my | nas | nam | cognates across Slavic |

Armenian (E) | 2pl | duk | jez | jez(a)nic | |

Albanian | 3sg(m) | ai | (a)të | atij | |

German | 3sg(m) | er | ihn | ihm | |

Kashmiri | 3sg(m) | su | təm’ | təmis | (remote)Footnote 78 |

Serbian | 3sg(m) | on | nje-ga | nje-mu | cognates across SlavicFootnote 79 |

Serbian | 3sg(f) | ona | nju | njoj | cognates across Slavic |

Serbian | 3pl(m) | oni | njih | njima | cognates across Slavic |

Romani (Kalderaš) | 3sg(m) | vo(v) | les | lés-kə | |

Romani (Kalderaš) | 3sg(f) | vój | la | lá-kə | |

Romani (Kalderaš) | 3sg(f) | von | le | lén-gə | |

Armenian (E) | emph | ink’e | iren | irenic | |

Dravidian: | |||||

Brahui | 1sg | ī | kane | kanki | |

Tamil | 1sg | naan | en | en-akku | also Malayalam |

1.3 A.3 ABC patterns

Language | Pronoun | Cases | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Unmarked | Marked 1 | Marked 2 | |||

Indo-European: | |||||

Albanian | 3sg.f | ajo | (a)të | asaj | |

Nakh-Dagestanian: | |||||

Khinalugh | 1sg | zɨ | jä | as(ɨr) | |

1.4 A.4 AAB patterns

Language | Pronoun | Cases | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Unmarked | Marked 1 | Marked 2 | |||

Algic: | |||||

Yurok | 3sg | yoʔ, woʔ, yoʔo⋅t, woʔo⋅t | yoʔo⋅t, woʔo⋅t | weyaʔik | |

Australian: | |||||

Gooniyandi | 1sg | nganyi | nganyi-ngga | ngaddagi | |

Gooniyandi | 3sg | niyi | niyi-ngga | nhoowoo | |

Jingulu | 1sg | ngaya | ngayarni, ngayirni | ngarr- | |

Jingulu | 2sg | nyama | nyamarni | ngaank-, ngank- | |

Mangarayi | 2sg | ñaŋgi | ña-n | ŋaŋgi | |

Wardaman | 3sg | narnaj | narnaj-(j)i | gunga | |

Wardaman | 3pl | narnaj-bulu | narnaj-bulu-yi | wurrugu | |

Yanyuwa | 3sg.m | alhi | alhinja | ayu | |

1.5 A.5 Other patterns (analysis unclear, but implausible as ABA)

Language | Pronoun | Cases | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Unmarked | Marked 1 | Marked 2 | |||

Australian: | |||||

Yidiny | 1sg | ŋayu | ŋaɲaɲ | ŋaḑu:nda ∼ ŋanda | |

Appendix B: Number

2.1 B.1 Languages studied

Language | Suppletion | Form | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

!Xhoo | none | Traill (1994) | |

Afrikaans | AB | Donaldson (1993) | |

Akwesansne Mohawk | none | Bonvillain (1973) | |

Aleut | none | Bergsland (1997) | |

Ambai | ABB | 1/2/3 | Smith (2011) |

Awtuw | ABB/ | 1/2 | Smith (2011) |

Bāgandji | none | Hercus (1982) | |

Bardi | ABB | 1incl/2/3 | Smith (2011) |

Basque | AB | de Rijk (2007) | |

Belait | ABC | 1/2 | Smith (2011) |

Berik | none | Westrum (1988) | |

Bilua | none | Obata (2003) | |

Biri | none | Smith (2011) | |

Boumaa Fijian | ABB | 1excl/1incl/2/3 | Dixon (1988) |

Bukiyip | ABB/ABC | 1/2/3m/3f | Smith (2011) |

Bunaba | ABB | 1excl/2/3 | Smith (2011) |

Burushaski | AB | Berger (1998) | |

Camling | none | Smith (2011) | |

Carib | none | Courtz (2008) | |

Cavineña | ABB/ABC | 1/3prox | Guillaume (2008) |

Chepang | none | Smith (2011) | |

Comanche | none | Charney (1993) | |

Crow | none | Graczyk (2007) | |

Dagaare | AB | Bodomo (1997) | |

Dehu | ABC/ABB/AAB | 1excl/1incl/2/3m | |

Djamindjung | ABB/ABC | 1excl/1incl/2/3 | Smith (2011) |

Dolakha Newar | none | Genetti (2007) | |

Dumi | none | van Driem (1993) | |

Dyirbal | none | Smith (2011) | |

Dzongha | none | van Driem (1992) | |

Eastern Pomo | AB | 1 | McLendon (1975) |

Evenki | none | Smith (2011) | |

Finnish | none | Karlsson (1999) | |

Flinders Island | ABC, | 1incl/2/3 | Smith (2011) |

Forest Enets | none | Smith (2011) | |

Gagadu | ABB/ABC | 1incl.m/1incl.f/3m/3f | Smith (2011) |

Gothic | ABB | 1/2 | Smith (2011) |

Gurinji | none | Smith (2011) |

2.2 B.2 ABB patterns

Below we list the plausible candidates of ABB patterns for number. Once more, as absolute numbers are not relevant, we have made educated guesses regarding what counts as a cognate.

Language | Pron | Numbers | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Singular | Plural | Dual | |||

Austro-Asiatic: | |||||

Semelai | 1excl | ʔəɲ | yeʔen | yε | |

Semelai | 1incl | ʔəɲ | hεʔen | hε | |

Mlabri | 2 | mεh | bah jum/Ɉum | bah | |

Austronesian | |||||

Kwamera | 1excl | iou | kɨmaha | kɨmrau | |

Kwamera | 1incl | iou | kɨitaha | krau | |

Kwamera | 2 | ik | kɨmiaha | kɨmirau | |

Kwamera | 3 | in | iraha | irau | |

Bukiyip | |||||

Bukiyip | 3m | énan / nani | omom mami | omom bwiom | |

Bukiyip | 3f | okok / kwakwi | owo wawi | echech bwiech | |

Bunaban | |||||

Bunaba | 1excl | ngayini | ngiyirriyani | ngiyirriway | |

Bunaba | 2 | nginji | yinggirriyani | yinggirriway | |

Bunaba | 3 | niy | biyirriyani | biyirriway | |

Djamindjungan | |||||

Djamindjung | 1excl | ŋayug | yirri | yirrinji | |

Djamindjung | 2 | nami | gurri | gurrinji | |

Djamindjung | 3 | dji burri | burrinji | ||

East Papuan | |||||

Lavukaleve | 1excl | ngai | e | el | |

Lavukaleve | 1incl | ngai | me | mel | |

Indo-European | |||||

Gothic | 1 | ik/mik | weis/uns(is) | wit/ugkis | |

Gothic | 2 | þu/þuk | jus/izwis | jut/igqis | |

Gunwingguan | |||||

Gagadu | 1incl.m | ngannj | manaada | manaamana | |

Gagadu | 1incl.f | ngannj | maneemba | manaanjdja | |

Ngandi | 1incl | njaka | ŋorrkorr | ŋorrkorni | |

Mangarayi | 2 | ŋiaŋgi | rnurla | rnurr | |

Gagadu | 3m | ngaayu | nowooda | nowoomana | |

Mirndi | |||||

Wambaya | 2 | nyamirniji | girriyani | gurluwani | |

2.3 B.3 ABC patterns

Language | Pron | Numbers | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Singular | Plural | Dual | |||

Austro-Asiatic | |||||

Jehai | 2 | mɔh/miʔ/paj | gin | jɨh | |

Austronesian | |||||

Dehu | 1excl | ini | eëhun(i) | nyiho | |

Belait | 1incl | kaw/ko(h), sakay’ | kitah, nyakitah | beh-debbeh | |

Belait | 2 | naw/no(h), ciw’ | (s)unyiw | beh(-debbeh), sebbeh | |

Bilua | |||||

Bilua | 2 | ngo | me | qe | |

Bilua | 3.m.sg.distal | vo | se | nioqa | |

Bukiyip | |||||

Bukiyip | 1 | yek | apak | ohwak | |

Bukiyip | 2 | nyak | ipak | bwiepu | |

Caviniña | |||||

Cavineña | 1 | ike | ekwana | yatse | |

Djamindjungan | |||||

Djamindjung | 1incl | ŋayug | yurri | mindi | |

East-Papuan | |||||

Savosavo | 2 | no | me | pe | |

Savosavo | 3m | lo | ze(po) | to | |

Gunwingguan | |||||

Gagadu | 3f | naawu | nowoomba | ngoyoonjdja/nowoonjdja | |

Nyulnyulan | |||||

Yawuru | 3 | ginjaŋga/yona | yerga/gaŋadjono | njambari/gadambari | |

Pama-Nyungan | |||||

Pitta-Pitta | 3m.near |

|

| pulayi | |

Pitta-Pitta | 3m.general |

|

| pulaka | |

Pitta-Pitta | 3m.far |

|

| pula:rri | |

Sepik-Ramu | |||||

Yimas | 1 | ama | ipa | paŋkt | |

Sino-Tibetan | |||||

Mongsen Ao | 1excl | ní | íla/îkhéla | kenet | |

2.4 B.4 AAB patterns

Language | Pron | Numbers | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Singular | Plural | Dual | |||

Austronesian | |||||

Dehu | 3m | angeice | angate | nyido | |

Mirndi | |||||

Wambaya | 1incl | ngawurniji, ngawu | ngurruwani | mirndiyani | |

Yagua | |||||

Yagua | 2 | jiy | jiryéy | sááda | |

2.5 B.5 Other patterns (analysis unclear, but implausible as ABA)

Language | Pron | Numbers | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Singular | Plural | Dual | |||

Austro-Asiatic | |||||

Mlabri | 1excl | ʔoh | ʔah jum, Ɉum | ʔah | |

East Papuan | |||||

Savosavo | 1excl | añi | ave | age | |

Lavukalave | 2 | inu | imi | imil | |

Gunwingguan | |||||

Ngandi | 1excl | ŋaya | njerr | njoworni | |

Mangarayi | |||||

Mangarayi | 1excl | ŋaya | ŋirla | ŋirr | |

Mangarayi | 1incl | ŋi | ŋarla | ŋarr | |

Pama-Nyungan | |||||

Flinders Island | 1incl | ŋayu | ŋalapal | ŋaluntu | |

Flinders Island | 2 | yuntu | yarra | yupala | |

Nyamal | 3 | palura | thanalu | piyalu | |

Nyamal | 3 | palura | thanalu | piyalu | |

Yanyuwa | 3m | (m)yiwa, (w)alhi | alu | wula | |

Sepik-Ramu | |||||

Awtuw | 2 | yen | om | an | |

Yagua | |||||

Yagua | 3 | níí | riy | naada | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, P.W., Moskal, B., Xu, T. et al. Case and number suppletion in pronouns. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 1029–1101 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9425-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9425-0

ABA

ABA ABA

ABA uwayi

uwayi anayi

anayi uwaka

uwaka anaka

anaka uw:rri

uw:rri ana:rri

ana:rri