Abstract

Businesses are gradually reopening as lockdown measures for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic are being relieved in many places across the globe. It is challenging but imperative for businesses to manage the risk of infection in the workplace and reopen safely. Drawing on risky decision-making theory and the job demands-resource model of workplace safety, we examined the influences of employees’ COVID-19 risk perception on their safety performance at work. On the one hand, COVID-19 risk perception motivates employees to perform safely; on the other hand, COVID-19 risk perception could also undermine safety performance through triggering anxiety. In an effort to find ways that alleviate the negative implications of risk perception, we also tested a cross-level interaction model where the risk perception–anxiety relation is weakened with a favorable team safety climate as well as low abusive supervision. Our data were collected from car dealership employees located in China in March 2020, when businesses just started to reopen in locations where these data were collected. Results showed that COVID-19 risk perception was positively related to anxiety, which in turn undermined safety performance. This negative effect canceled out the direct positive effects of COVID-19 risk perception on safety performance. In addition, cross-level interaction results showed that the buffering effect of team safety climate on the risk perception–anxiety relation was diminished with an abusive supervisor. Our findings provide valuable and timely implications on risk management and workplace safety during a public health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

It has been more than a year into the pandemic caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19; World Health Organization, 2021). With vaccines rolling out and hospitalization reduced, the pandemic is still ongoing and the risk of COVID-19 infection is still lingering. As many areas have eased lockdown measures and businesses that were put on hold during the lockdown have gradually begun to reopen, it is imperative for businesses to prepare themselves and their workers for the potential outbreak of COVID-19 so as to reduce the impact of the pandemic on businesses, workers, customers, and the public (US Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], 2020). Employees who have to return to working on site are still faced with the risk of COVID-19 infection, in which condition adhering to relevant safety procedures becomes especially important. Preparing for safe reopening under the risks of an ongoing pandemic, however, could be challenging for businesses.

While employees may be motivated to implement and adhere to relevant safety procedures when perceived COVID-19 risks are high, such risks could also elicit strong negative affective states such as anxiety, which may nevertheless undermine safety performance as coping with these negative affective states requires mental resources that could have been devoted to performing safely (Rudolph et al., 2021; Wells et al., 1999). Such a dilemma has raised an important question for organizational researchers and practitioners: How to alleviate the potential negative effects caused by the perceived risks of COVID-19 so that they trigger more (rather than less) safety behavior toward containing the spread of the COVID-19 virus during the pandemic?

Partly responding to this issue, research in risky decision making (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992) and the job demands-resources (JD-R) model of workplace safety (Beus, et al., 2016; Nahrgang et al., 2011) has suggested that building up a favorable safety climate is critical. Applying the concept of safety climate (Christian et al., 2009; Zohar, 2003) to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we argue that a COVID-19 safety climate should reflect the shared perceptions of workplace safety policies, practices, and procedures aimed at mitigating the spread of COVID-19. A favorable safety climate would buffer the extent to which COVID-19 risk perception leads to anxiety, as it provides organizational and social resources to support employees in dealing with such risks (Nahrgang et al., 2011) and a strong situation that channels individuals’ attention and behaviors toward safety maintenance rather than staying anxious and panicking (Meyer et al., 2010; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). Indeed, recent scholarly discussions have suggested that the safety climate could be an important protection mechanism through which organizations can alleviate the negative influences of COVID-19 (e.g., Rudolph et al., 2021; Sinclair et al., 2020). These propositions, however, have not been empirically tested, to the best of our knowledge. Moreover, although the safety climate could provide a contextual protection mechanism for employees to deal with COVID-19 risks, we argue that employees’ capacity to benefit from a favorable safety climate largely depends on their experiences with supervisors. Supervisors are among the people in the workplaces with whom employees work most closely on a daily basis. Past research has pointed out that having a positive relationship with a supervisor not only directly influences employee safety performance, but also interacts with the safety climate to further enhance safety performance (e.g., Hofmann et al., 2003). While research has also shown that negative experience with a supervisor (i.e., abusive supervision) influences safety performance (e.g., Yang et al., 2020), little is known about whether and how abusive supervision influences safety performance in conjunction with the safety climate. Given the challenges of a public health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, it is likely that the supervisor could be an important contextual boundary condition for whether and when the safety climate serves as an effective protection mechanism for employees. As such, we deem it important to examine the interaction between abusive supervision and the safety climate to better understand how to optimize the benefit of the safety climate.

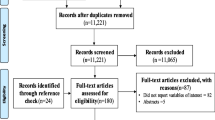

In this study, we seek to address these issues with a multilevel model (Fig. 1). We propose that COVID-19 risk perception influences safety performance both directly and indirectly through anxiety. Specifically, the extent to which COVID-19 risk perception leads to anxiety depends on the team safety climate, which further depends on abusive supervision. In our research, we intend to make two major contributions. First, we provide a better understanding of the psychological mechanism of risky decision making at work by examining anxiety as an affective reaction to an employee’s perceived risks of COVID-19.

Hypothesized Model. Notes. H = hypothesis (e.g., H1 = Hypothesis 1). A plus ( +) sign in parentheses indicates that we expect a positive bivariate relation or an enhancement-type interaction. A minus (-) sign in parentheses indicates that we expect a negative bivariate relation or an attenuation-type interaction

Further introducing a mental resource perspective (Wells et al., 1999) to risky decision making, we argue that anxiety drains mental resources and therefore serves as a counteracting force to the positive effect of COVID-19 risk perception on safety performance. Second, echoing recent proposals (Rudolph et al., 2021; Sinclair et al., 2020), we not only empirically test the safety climate as a situational buffer of the COVID-19 risk perception–anxiety relation, but also set up abusive supervision as a boundary condition for the moderating effect of the safety climate. In other words, we extend current research on the safety climate by examining three-way interactions between risk perception, team safety climate, and abusive supervision in influencing safety outcomes.

Results from these interactional models will advance our knowledge about whether and when the safety climate could be beneficial. In the broader context of a global pandemic where both individual efforts and collective actions are needed, knowledge about these boundary conditions would be especially helpful for both researchers and organizations to better design policies and allocate resources to ensure that the economy opens safely during the ongoing pandemic.

Theory and Hypothesis Development

Risk Perception and Anxiety under COVID-19

To develop our model, we start with understanding the effect of COVID-19 risk perception on anxiety. According to the “risk of feelings” perspective in risky decision making (Loewenstein et al., 2001), risk perception includes both people’s emotional reactions toward a hazard and the cognitive evaluations about the hazard (e.g., Dryhurst et al., 2020; Sjöberg, 1998) such as COVID-19. For instance, the emotional reactions about the risks of COVID-19 reflect the extent to which people are worried about getting COVID-19 (referred to as worry hereafter). In comparison, the cognitive evaluations often refer to the likelihood that people think they would contract COVID-19 (referred to as likelihood hereafter). Moreover, the “risk as feelings” perspective hypothesizes that emotional reactions to a risky situation could diverge from cognitive evaluations about the risks (Loewenstein et al., 2001). Indeed, past research has shown that worry and likelihood are independent dimensions and they each capture unique variance in the judgments about risks (e.g., Shiloh et al., 2013; Sjöberg, 1998).

COVID-19 has caused hundreds of millions of identified cases and millions of casualties around the world since the disease was first identified in late 2019 (World Health Organization, 2021). There are, however, still many unanswered questions about this disease, such as how easily the virus is spread and what methods could be most effective in curing the disease. Therefore, COVID-19 is widely perceived to be a very risky event given the severity of its consequences and the uncertainty surrounding the disease (Dryhurst et al., 2020). Because of such severity and uncertainty, high levels of risk perception can trigger strong affective reactions, especially anxiety (e.g., Morrow & Crum, 1998; Pauley et al., 2008; Turner et al., 2006). We expect that anxiety would be linked to risk perceptions related to health and safety, and more broadly, to risk perceptions about hazards that are unknown and could render negative, severe consequences. However, due to the study design in this paper, we focus on workplace health and safety concerning COVID-19 risk.

Anxiety refers to a state of fear, nervousness, discomfort, etc., induced by situations perceived as dangerous (Loewenstein et al., 2001; Sheeran et al., 2014).Footnote 1 As businesses reopen during the pandemic, employees who have to come back to work likely feel anxious if they perceive COVID-19 to pose risk. The JD-R model of workplace safety (Nahrgang et al., 2011) suggests similar relations. According to this model, risks and hazards at work are categorized as job demands, which lead to negative worker well-being, including anxiety. Risk perceptions about COVID-19 therefore cast additional job demands for which employees will have to spend additional resources to deal with, on top of their normal job tasks, and they will feel anxious if they do not have enough resources in this situation. As such, we propose that:

COVID-19 risk perception is positively related to anxiety.

Anxiety as a Mediator in the Risk Perception–Safety Performance Relation

One of the most concerning consequences of risk-induced anxiety is its potential harm to safety performance. Analogous to the task versus contextual distinction regarding job performance, safety performance includes safety compliance and safety citizenship behavior (Neal & Griffin, 2004). Safety compliance reflects “the core safety activities that need to be carried out by individuals to maintain workplace safety” (Neal & Griffin, 2004, p. 349). In comparison, safety citizenship behavior reflects voluntary behaviors aimed at improving the safety performance of the organization and of other colleagues (Hofmann et al., 2003). In this study, we focused on COVID-specific safety performance to better understand workplace safety during the pandemic.Footnote 2 An employee can, for instance, display safety compliance by wearing personal protective equipment (e.g., masks) at work and sanitizing the workspace regularly. An employee may also display safety citizenship by helping a busy colleague to sanitize the workspace or voicing suggestions to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection in the organization.

As both types of safety performance are aimed at preventing or reducing the risks of COVID-19, it should be intuitive that safety performance is directly linked to employees’ perceptions about the risks of COVID-19. Indeed, theoretically, risk perception is argued to be positively related to safety compliance as people seek safety to avoid risky situations (e.g., Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). Empirically, however, studies only found a positive but weak relation between risk perception and safety compliance (e.g., Taylor & Snyder, 2017; Xia et al., 2017) or health-related preventative behaviors in general (e.g., Sheeran et al., 2014). One explanation could be that anxiety, as a direct result of risk perception, undermines safety performance.Footnote 3 Neuroscience evidence has shown that anxiety drains people’s mental resources and reduces their ability to exert cognitive and behavioral control (Bishop et al., 2004; Fox et al., 2005). The lack of mental resources makes it hard for people to make optimal decisions about the risk, e.g., anxious people may forget or refuse to take preventative measures to reduce the risk of diseases even if these measures are what should have been best for them in such situations (Slovic et al., 2007). Moreover, people also tend to be reluctant to take preventative measures as these measures remind them about the existence of the risks. Research in health psychology, for instance, found that women who feel anxious about the risk of breast cancer are more reluctant to take breast self-examination (e.g., Murray & McMillan, 1993).

Similarly, according to the JD-R model of workplace safety (Nahrgang et al., 2011), risk perception poses a job demand that makes employees anxious due to increased psychological costs, which in turn leads to more unsafe behaviors, accidents, and injuries. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, risk perception about COVID-19 makes employees anxious while working during the pandemic, which further drains their mental resources, leaving limited resources available for them to devote additional effort to comply with the safety requirements at work (safety compliance). Moreover, for those who are already anxious and resource drained, it would be difficult for them to exert even more mental and physical resources to go above and beyond to help or advise others about improving safety measures (safety citizenship behaviors). In sum, whereas risk perception elicits higher levels of anxiety, anxiety nevertheless undermines safety performance. In this vein, anxiety displays a suppression effect between risk perception and both safety compliance and safety citizenship behavior. As such, we propose that:

Anxiety mediates the effects of COVID-19 risk perception on (a) safety compliance and (b) safety citizenship behavior, such that COVID-19 risk perception is positively related to anxiety, which then negatively relates to safety compliance and safety citizenship behavior.

Team Safety Climate as a Buffer in the Risk Perception–Anxiety Relation

Given that anxiety was proposed was a suppressing mediator of the relation between risk perception and safety performance, to encourage safety performance during the pandemic, it is important for organizations to help employees reduce the level of anxiety elicited by the risks of COVID-19 (Van Bavel et al., 2020). One solution serving this purpose will be building up a positive team safety climate at work. Given that risk perception and anxiety are experienced by individual employees nested within teams, the relation between these variables may also vary across teams with different levels of safety climate. Therefore, as an important contextual resource for coping with risks at work, the safety climate is expected to mitigate the effect of COVID-19 risk perception on anxiety.

According to the JD-R model, whereas perceived risk about safety poses additional job demands that employees have to spend additional resources to deal with, the safety climate could function as both social and mental resources that support employees in dealing with such risks (Nahrgang et al., 2011). It has been proposed that a positive safety climate at work is an important protection mechanism through which organizations and managers can support frontline employees with necessary resources and boost their capabilities to deal with the risks of COVID-19 infection (Beus et al., 2016; Rudolph et al., 2021). COVID-19 poses a public threat where collective actions are required to reduce the risk of virus transmission. A favorable safety climate signals that the team takes COVID-19 risks seriously and that its members are required to follow relevant safety protocols and engage in safety-keeping behaviors to keep everyone safe at work. In such a favorable safety climate, safety behaviors are encouraged, safety protocols are followed, and, as such, an employee who perceives COVID-19 to be risky would feel more protected. Employees would feel that they have more resources in dealing with the risks and hence are less likely to be anxious.

In comparison, in an environment with a low level of safety climate, people do not feel that the company values safety procedures or complies with COVID-19 safety guidelines. In situations like this, employees would feel that they are always on their own and do not have the necessary resources in dealing with the risks of COVID-19. As a result, with a low level of safety climate, risk perception is more likely to elicit anxiety. Conversely, a favorable safety climate can also reduce the likelihood of anxiety by building up a strong situation (Meyer et al., 2010; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992) where employees pay more attention to workplace safety and risk reduction rather than staying anxious and panicking about COVID-19 infection. As such, we propose that:

The team safety climate moderates the COVID-19 risk perception-anxiety relation. This relation is weaker when the team safety climate is high than when it is low.

A Boundary Condition of Safety Climate’s Buffering Effect

Although the safety climate generally reduces the levels of anxiety induced by COVID-19 risks, we argue that this moderating effect depends on a vital player—supervisors at work. We posit that the safety climate is less effective in serving as a protection mechanism that prevents employees from feeling anxious if such a climate is implemented by an abusive supervisor. In other words, we propose that abusive supervision serves as a critical boundary condition for the moderating effect of the safety climate.

Abusive supervision refers to supervisors’ engagement in the display of nonphysical, hostile verbal, and nonverbal behaviors (Tepper, 2000). According to the JD-R model, experience of abusive supervision adds additional job demands that employees have to spend resources to deal with. Targets of abusive supervision are more likely to feel emotionally exhausted, anxious, and dissatisfied, as they are faced with higher cognitive and emotional demands trying to cope with such hostility from their supervisor (Tepper et al., 2004; Whitman et al., 2014). Moreover, abusive supervision would also distract employees from the resources that are supposed to support them in dealing with other job demands as abusive supervision signals to an employee that they are not a valued team member (Yang et al., 2020). Specifically, abusive supervision breaks the protection mechanism of the safety climate as such a toxic situation makes it harder for the safety climate to compensate for the resources needed to cope with the emotional and cognitive demands that an employee already faces due to the risks of COVID-19. Victims of abusive supervision would also feel that they are treated unfairly compared to the other members of the team and hence are excluded from receiving the resources or protections provided by the safety climate in the team. In other words, the safety climate should only buffer the relation between risk perception and anxiety for employees who experience low levels of abusive supervision. As such, we propose that:

Abusive supervision moderates the negative interactive effect of the safety climate and COVID-19 risk perception on anxiety in such a way that this interaction only occurs when abusive supervision is low.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Employees from a car dealership group were recruited via email. Employees were asked to complete two online surveys with approximately one-month in between each administration. The surveys were administered to employees in the car dealership’s retail branches across China, in March and April 2020. The timing of the data collection provided a unique context for us to examine workplace safety as businesses were going through the reopening phase during an ongoing pandemic. At the time when our data were collected, the lockdown restrictions were lifted and businesses were starting to reopen in most places in China, yet it was also around the same time when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic (Timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2021).

It was hence important for the reopened businesses in China to prepare themselves and their employees for the possibility of potential worsening outbreak conditions during the pandemic. In addition, the sample of car dealership employees were also appropriate for testing our hypotheses in that car dealers may often have contacts with the general public as potential customers, which could expose these employees to higher risks of COVID-19 infection when there was ongoing community transmission. As such, our sample provided a unique but appropriate context for us to test our hypotheses.

The final sample consisted of 390 employees within 82 teams (i.e., branches) with team size ranging from two to 13, representing 98% of all participants who consented to participate in the study and 65% of all the employees contacted for participation. Participants were 59% male, ranging from 18 to 56 years old (M = 29.04, SD = 6.04). On average, participants worked in the focal company for 2.81 years (SD = 2.32). Participants answered questions about demographics (e.g., age, sex), COVID-19 risk perception, safety climate, and abusive supervision at Time 1. Four weeks later, at Time 2, anxiety and safety performance (including safety compliance and safety citizenship behavior) were measured. The surveys were originally written in English and then translated into Chinese using the back-translation procedure recommended by Brislin (1970). Surveys were matched between waves using employee ID numbers.

Measures

COVID-19 risk perception

Following previous research (e.g., Shiloh et al., 2013; van der Linden, 2015), our measure of COVID-19 risk perception reflects both its emotional aspect: worry (“How worried are you about getting COVID-19?” 1 = not at all worried, 5 = very worried) and its cognitive aspect: likelihood (“How likely do you think you would contract COVID-19?” 1 = not at all likely, 5 = very likely). In comparing across these two dimensions, we found that whereas most employees believed it was unlikely that they would get infected (median = 2, mean = 2.01), most of them were worried about COVID-19 infection (median = 4, mean = 3.62). The difference between the cognitive and emotional risk perceptions seems to have been the reason for the low correlation between these dimensions (rworry—likelihood = 0.22). Based on these results, we decided that it was more appropriate to treat them as separate constructs. As such, in the current study we analyzed and reported the results for the worry and likelihood dimensions separately.

Abusive supervision

Abusive supervision was measured by Mitchell and Ambrose’s (2007) 5-item scale. Participants responded to a 5-point frequency scale (1 = Never; 5 = Always) about their perceptions of their direct manager (e.g., “My manager puts me down in front of others.” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93). This variable was log transformed before the regression analyses as its distribution was right-skewed (skewness = 3.11).

We viewed abusive supervision as an individual-level, rather than team-level construct, for both theoretical and empirical reasons. Although all employees in the same team have the same supervisor, the supervisor may exhibit different levels of abusive supervision toward different subordinates. This is also why abusive supervision is dominantly conceptualized and measured at the individual level in the literature, reflecting how a subordinate views their supervisor’s behavior to them (Fischer et al., in press). A further look at the ICC values further supported that abusive supervision is not appropriate to be viewed as a team-level construct, as between-team variance only accounted for a trivial amount of the total variance in abusive supervision (ICC(1) = 0.01, ICC(2) = 0.05).

Team safety climate about COVID-19

We adapted the wordings of Huang et al.’s (2017) four-item team safety climate measure to make it COVID-19-specific (e.g., “My manager frequently talks about COVID-19 safety issues throughout the work week.” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95). Participants rated the items on a five-point scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree”; 5 = “Strongly Agree”).

In support of aggregating individual scores of safety climate to the team level, we assessed within-team reliability and agreement using three measures: the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs), including both ICC(1) and ICC(2), and rwg(j) (James et al., 1984; LeBreton & Senter, 2008). The ICC(1) value was 0.14, indicating that team membership accounted for 14% of the variance in individual ratings of safety climate. ICC(2) ranged from 0.24 (team size = 2) to 0.67 (team size = 13), with ICC(2) = 0.39 for a median team size of four. The relatively low ICC(2) values, which indicate that mean scores may not reliably distinguish across teams, could be due to the small numbers of members per team (Bliese, 1998). We also obtained an rwg(j) of 0.95 across teams based on a uniform null distribution of random responses (expected error variance = 2.00) and of 0.92 based on a distribution slightly skewed by response bias (expected error variance = 1.33). There was, however, considerable variability in rwg(j) across teams, as shown by the frequency distribution plots of rwg(j) (Fig. 2). Thus, we decided to aggregate individual scores of safety climate up to the team level, yet we also recognized that there was between-team variability in the within-team agreement of climate scores. Such variability also supported the potential of examining the three-way interactions as we have proposed in the current study.

We calculated the correlations between team size and team-level anxiety, safety compliance, and safety citizenship behaviors. None of the correlations were significantly different from zero: r = -0.13 for the team size–anxiety relation, r = 0.08 for the team size–safety compliance relation, and r = 0.11 for the team size–safety citizenship behaviors relation. These results showed that team size did not account for the variance in anxiety, safety compliance, and safety citizenship behaviors.

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured with six items from Daniels et al. (1997). Participants responded about how frequently (1 = Never; 5 = Always) they experienced the emotional states described in each item (e.g., anxious, tense) during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84).

COVID-19-Specific Safety Compliance

We adapted the wordings of Griffin and Neal’s (2000) four-item safety compliance scale to make it COVID-19-specific (e.g., “I use all the necessary equipment to avoid exposure to COVID-19 when doing the job.” Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). Participants responded to a 5-point scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree”; 5 = “Strongly Agree”).

COVID-19-Specific Safety Citizenship Behavior

We adapted Hofmann et al.’s (2003) safety citizenship behavior measure to make it COVID-19-specific, which captures both safety helping (four items) and safety voice (six items). Sample items include “I volunteer for COVID-19 safety committees” for safety helping and “I make COVID-19 safety recommendations about work activities” for safety voice (1 = “Strongly Disagree”; 5 = “Strongly Agree”). These two sub-dimensions were highly correlated (r = 0.75, p = 0.00), so we decided to combine them into one construct (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90).

Control variables

Sex and age were controlled as risk perception and risk-aversive behaviors such as safety performance tend to vary depending on sex and age (e.g., Byrnes et al., 1999; Mata et al., 2011).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Measurement Model

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables. Echoing previous research in health psychology that found weak relations between risk perception and safety behaviors (e.g., Brewer et al., 2007; Sheeran et al., 2014), our results showed that the risk perception of worry had small correlations with safety compliance (r = -0.01) and safety citizenship behaviors (r = 0.05), both of which were nonsignificant. The risk perception of likelihood had small-to-medium negative correlations with safety compliance (r = -0.14) and safety citizenship behaviors (r = -0.12), with both correlations being significantly different from zero. These results set the basis for us to further examine the suppression effects of anxiety between risk perception and both types of safety performance.Footnote 4

Table 2 presents the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results to test the factor structure of the overall measurement model. We used the lavaan R package (Rosseel, 2012) and used maximum-likelihood estimation (MLM) with robust standard errors. Model fit was assessed with the \({\upchi }^{2}\) statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The initial results revealed that the seven-factor model had the best fit with the observed data, compared to other CFA models. This model, however, did not present a satisfactory fit compared to the data based on Hu and Bentler’s (1999) recommended cutoff values. A detailed examination of results suggested that the three reversed-loaded items in anxiety had low factor loadings (0.28, 0.31, and 0.38, respectively) on the latent factor of anxiety, which contributed to the non-satisfactory model fit (Courtright et al., 2014; Richards & Schat, 2011). We then examined an alternative seven-factor model without these reversed-coded items, and results suggested a satisfactory model fit. These results provided evidence of the discriminant validity of all latent constructs.Footnote 5

Direct and Indirect Effects

Table 3 presents the hierarchical linear modeling results for Hypotheses 1 to 4. Supporting Hypothesis 1, the COVID-19 risk perception of worry was positively related to anxiety (γ = 0.13, p = 0.00), and the COVID-19 risk perception of likelihood was positively related to anxiety (γ = 0.09, p = 0.04).

In support of Hypothesis 2, anxiety was negatively related to COVID-19 safety compliance (γ = -0.40, p = 0.00) and COVID-19 safety citizenship behavior (γ = -0.15, p = 0.00) after taking the COVID-19 risk perceptions (both worry and likelihood) into account. Monte Carlo simulation was then performed using the mediation R package (Imai et al., 2010; Tingley et al., 2014) to further test the indirect effect of the COVID-19 risk perceptions of worry and likelihood on safety performance through anxiety. Monte Carlo results based on 5,000 simulations indicated that anxiety mediated the effects of worry on safety compliance (indirect effect = -0.06, 95% CI = [-0.09, -0.03]) and on safety citizenship behavior (indirect effect = -0.05, 95% CI = [-0.07, -0.02]). Similarly, results from the Monte Carlo simulations indicated that anxiety mediated the effects of likelihood on safety compliance (indirect effect = -0.05, 95% CI = [-0.09, -0.02]) and on safety citizenship behavior (indirect effect = -0.04, 95% CI = [-0.07, -0.01]).

As shown in Table 3, we did not find a significant two-way interaction between abusive supervision and risk perception in influencing anxiety. Moreover, our three-way interaction results provided further evidence why the two-way interaction might be nonsignificant. Our results showed that abusive supervision only exacerbated the risk perception–anxiety relation when the safety climate was also high. As shown in the three-way interaction results (e.g., right-hand side of Figs. 3 and 4), the risk perception–anxiety relation was strong and positive when abusive supervision and safety climate were both high; in comparison, the relation was small (and almost turned negative) when abusive supervision was high but the safety climate was low. These results suggested that abusive supervision functioned very differently under high versus low conditions of the safety climate, and such divergent relationships were masked in the two-way interaction results. It is worth pointing out that, after taking anxiety into consideration, the risk perception of worry had a positive direct effect on safety compliance (γ = 0.08, p = 0.01), whereas likelihood had a negative direct effect on safety compliance (γ = -0.12, p = 0.02). In comparison, worry had a positive direct effect on safety citizenship behavior (γ = 0.06, p = 0.01), whereas likelihood had a nonsignificant direct effect on safety citizenship behavior (γ = -0.07, p = 0.06).

As such, although anxiety mediated the effects of both the worry and likelihood dimensions of risk perception on safety performance, it only displayed a suppression mediating effect between worry and safety performance, but not between likelihood and safety performance. In other words, our results indicated that the cognitive and affective aspects of COVID-19 risk perceptions have divergent effects on safety performance.

Cross-Level Interactions

Next, we performed cross-level interaction analyses using the nlme R package (Pinheiro et al., 2022).Footnote 6 As shown in Table 3, the team safety climate did not significantly moderate the worry–anxiety relation (γ = 0.06, p = 0.40) or the likelihood–anxiety relation (γ = 0.00, p = 0.99). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was not supported.

We then examined the three-way interaction effects of abusive supervision. Overall, our results supported Hypothesis 4. As shown in Table 3, the interactive effect of worry, safety climate, and abusive supervision on anxiety was significantly positive (γ = 0.68, p = 0.00). To further probe this interaction effect, we performed simple slope analyses for each regression line under different levels of abusive supervision, to compare the different moderating effects of safety climate in each condition (Aiken et al., 1991).

Specifically, under conditions of low abusive supervision, the risk perception of worry significantly predicted anxiety when the safety climate was low (γ = 0.19, p = 0.00), but it did not predict anxiety when the safety climate was high (γ = 0.09, p = 0.11). In comparison, under conditions of high abusive supervision, the risk perception of worry did not predict anxiety when safety climate was low (γ = -0.01, p = 0.88), but it significantly predicted anxiety when safety climate was high (γ = 0.22, p = 0.00). The interaction patterns among these variables are illustrated in Fig. 3.

As shown in Table 3, the interactive effect of the risk perception of likelihood, safety climate, and abusive supervision on anxiety was positive (γ = 1.04, p = 0.00). Moreover, simple slope analyses showed that, under conditions of low abusive supervision, the risk perception of likelihood significantly predicted anxiety when safety climate was low (γ = 0.19, p = 0.04), but it did not predict anxiety when safety climate was high (γ = -0.05, p = 0.61). Under conditions of high abusive supervision, risk perception of likelihood did not predict anxiety when safety climate was low (γ = 0.00, p = 0.99), but it significantly predicted anxiety when safety climate was high (γ = 0.27, p = 0.00). The interaction patterns are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Discussion

Using the data collected from a sample of car dealership employees when businesses just started to reopen in China in March 2020, we tested a multilevel model where the COVID-19 risk perception–anxiety relation was expected to be weakened with a favorable team safety climate as well as low abusive supervision. Results showed that COVID-19 risk perception was positively related to anxiety, which in turn undermines safety performance. This negative effect canceled out the direct positive effects of COVID-19 risk perception on safety performance. In addition, cross-level interaction results showed that the buffering effect of team safety climate on the risk perception-anxiety relation was diminished with an abusive supervisor. Our findings provide valuable and timely implications on risk management and workplace safety during a public health crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, as we discuss below.

Research Implications

In this study, we examined the risk perceptions about COVID-19 and its effect on employees’ affective reactions and COVID-19-related safety performance during the pandemic. By simultaneously examining the effects of the emotional and cognitive dimensions of risk perception on anxiety and safety performance, our results provide robust evidence for the “risk as feelings” perspective on risky decision making (Loewenstein et al., 2001). Echoing this perspective, we only found a medium correlation between worry and likelihood (r = 0.22). We also showed that worry and likelihood displayed different patterns of effects on safety performance.

As such, these different patterns of effects for the emotional and cognitive aspects of risk perception demonstrate the diverging but complementary roles of the emotional and cognitive systems, respectively, in risky decision making (Loewenstein et al., 2001; Sjöberg, 1998). The different patterns of effects for worry and likelihood may also relate to the differences between levels of worry and likelihood that we observed in our sample. Our data were from employees located in areas of China outside of Hubei province, where COVID-19 had just rendered a month-long lockdown nation-wide (hence the high perceptions of worry) but was largely under control in March 2020 when the data were collected (hence the low perception of likelihood).

The low likelihood perception may also partly be due to optimism bias that underestimates the likelihood of bad things happening to oneself (e.g., van Bavel et al., 2020; Weinstein, 2000). Given the perceived low likelihood of infection, people might not have considered it necessary to take safety measures, which may explain why we found that likelihood did not influence, or even weakly undermined, safety performance. On the contrary, the high levels of worry perceptions kept people wary of the potential harms of COVID-19, and hence, we observed a positive effect of worry on both types of safety performance in the regression results (Table 3). In this vein, our findings demonstrate the importance of keeping an appropriate level of worry and wariness in maintaining workplace safety as businesses reopened after the strict lockdown.

Keeping an appropriate level of wariness, however, does not suggest that anxiety is beneficial. Echoing previous theoretical propositions (e.g., van Bavel et al., 2020), our results demonstrate that anxiety, a strong but negative affective state, could bias people’s information processing about health risks and hence undermine safety performance. Specifically, we found a negative relation between anxiety and safety performance during the pandemic, i.e., a higher level of anxiety is related to more risk taking. Although this may seem contrary to what is typically depicted in past research where higher anxiety is related to less risk taking (e.g., Loewenstein et al., 2001), our finding shared the same the underlying core with the previous findings: strong but negative affective states such as anxiety undermine people’s mental resources and biases their risky decision making (e.g., Schwarz, & Clore, 1983; Slovic et al., 2007). As a result, in the work domain and under the context of a global pandemic, anxiety leads people to act less safely, even if acting safely is the more optimal choice. Given that anxiety stands at the center of such a heuristic, preventing such strong but negative emotions is the key to alleviating the unwanted effect of these negative emotions on risk taking.

To this end, by examining the buffering effect of safety climate in the risk perception–anxiety relation, we have not only echoed theoretical propositions about the importance of workplace safety climate during a public health crisis (e.g., Rudolph et al., 2021; Sinclair et al., 2020), but have expanded upon prior research by offering abusive supervision as a boundary condition of the positive roles of safety climate. Going beyond previous research that found a negative relation between abusive supervision and safety climate (e.g., He et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2016), we further showed that abusive supervision interacts with safety climate in influencing safety performance. Based on different experiences of abusive supervision, employees interpret and react differently to the team’s safety climate. Employees who experienced both a high safety climate and abusive supervision may be more anxious, probably because they feared making mistakes when implementing the strict safety protocols and, as a result, drawing the attention or even criticism from the abusive supervisor. These employees may also be anxious because, compared to other colleagues, they received less support from the supervisor and had to be on their own when implementing the strict safety rules.

Overall, our findings showed that the benefits of safety climate would also depend on how safety protocols are implemented and how safety climate is reinforced, in both of which supervisors would play an important role. More research should thus be conducted on what supervisors should or should not do when implementing safety procedures and promoting safety climate to enhance safety at work.

Practical Implications

Our findings also provide substantial practical implications, particularly regarding managing the risk of COVID-19 as businesses reopen during an ongoing pandemic. With the risk of COVID-19 infection still lingering, businesses should care about whether and to what extent the perceived risk of COVID-19 would elicit employees’ emotional reactions such as anxiety. Moreover, measures should be taken to buffer the negative impacts of COVID-19 risk perception such that employees are not overly anxious about the risk of COVID-19.

One important measure, then, would be to build up a favorable safety climate where employees can feel protected and supported while coming back to work. Businesses and employers could, for instance, make sure that they and their employees are updated with the official COVID-19 safety guidelines for workplaces (e.g., US Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], 2020; U.S. Centers of Disease Control, 2021) and that their daily operations fully comply with these guidelines. Businesses may also build up a favorable safety climate by setting up policies, incentives, and norms such that employees feel safe to be tested or self-isolated without worrying about being punished or losing their jobs due to these safety measures. As vaccines become available, a favorable safety climate could also include policies or incentives that encourage employees to be vaccinated.

Finally, our findings suggest that businesses and employers should note that safety climate could be less beneficial or even detrimental when a supervisor communicates and reinforces safety policies to some team members in an abusive way. Threatening a pregnant employee that she would be fired if she chooses not to be vaccinated before coming back to work, for instance, would exacerbate the employee’s anxiety even if vaccination is intended to build up a favorable safety climate in the workplace during the pandemic.

Collective efforts are essential in a public health crisis involving infectious diseases. As such, rather than forcing COVID-19-related safety procedures and policies unilaterally onto employees, it would be important for employers and supervisors to collaborate with all employees to designate effective means of implementing and communicating these safety procedures and policies during the pandemic.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study has a few limitations that could open avenues for future research. First, because the pandemic is unprecedented, in the current study, we adapted the existing measures of safety performance, assuming that these assessments could be applicable to all workplace hazards, including infectious diseases such as COVID-19 and influenza. To better understand workplace safety during a public health crisis and help businesses better prepare for infectious diseases, however, it may be helpful to develop thorough assessments of safety performance that are specific to infectious diseases.

One promising starting point is to build upon the list of infection prevention measures that US Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA] (2020) provided and use objective or other reported assessments to examine the extent to which these measures have been followed by employees. Moreover, combating infectious diseases requires the collective efforts of businesses, employees, and the public. As such, pandemic-specific safety citizenship behaviors may involve behaviors aimed at not only colleagues and employers, but also the community where the business is embedded.

Future research may also test whether and how risk perception relates to risk-reduction behaviors during the pandemic, as our findings also revealed that the COVID-19 risk perception of worry to be positively linked to both safety compliance and safety citizenship behavior after accounting for anxiety as a mediator. For instance, based on the “risk as feelings” perspective, researchers could examine the influences of risk perception, especially its emotional aspect such as worry, on people’s cognitive evaluations during the pandemic, and whether how such cognitive evaluations diverge from emotional reactions such as anxiety. For example, they could examine whether and how the risk perceptions of worry and likelihood may influence employees’ evaluations about the benefits of workplace safety protocols against infectious diseases, such as hand washing and mask wearing. Researchers could also examine whether and to what extent employees’ cognitive and emotional risk perceptions would influence how they weight the benefits of safety protocols in their decisions to comply.

Of relevance here is health psychology research that has shown that perceived self-efficacy in dealing with the risk would interact with the risk perception in influencing the intention and the actions for risk reduction (e.g., Schwarzer, 2008; Sheeran et al., 2014). In this vein, future research could also examine whether and how the perceived effectiveness and accessibility of protective equipment and other safety protocols would contribute to the perceived self-efficacy.

Moreover, both risk perception and risky decision making are often influenced by individual differences such as one’s propensity to take or avoid risks (e.g., Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). It would therefore be important to examine the impacts of such individual differences, or at least control for their potential impacts, when examining risk perception and risky behaviors during the pandemic. Findings from these lines of research could not only help researchers to better understand the roles of cognitive and emotional systems in risky decision making, but also help businesses to better educate and communicate to their employees about the importance of safety measures during a public health crisis such as COVID-19.

Finally, both organizational research and practices would benefit from better understandings about the roles of leadership in times of crisis, especially a public health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings suggest that a favorable team safety climate may not equally benefit all employees as some employees may be unfairly treated (e.g., Gyekye & Haybatollahi, 2014). Traditional research on workplace safety, for instance studies that examine the safety of truck drivers or construction workers, rarely have to take into consideration whether and to what extent the safety outcomes of an employee may influence others around them. COVID-19, however, has posed a unique and novel challenge to organizational researchers and practitioners due to its highly infectious nature. One infected employee may endanger other employees, threaten whether the business can remain open, and even expose the entire community to the attack of the virus. Therefore, both individual and collective efforts are needed to promote workplace safety during the pandemic. Whereas managers and supervisors play important roles in implementing and motivating such efforts, we have demonstrated that mistreatment by a supervisor would nevertheless undermine the effects of collective safety at work.

It would therefore be worthwhile for future research to examine the best way for businesses and managers to support employees with the necessary resources during crisis, to communicate and reinforce safety climate in a way that aligns both individual and collective interests, and to motivate both individual and collective actions to enhance workplace safety during the pandemic.

Notes

Anxiety and worry may sound conceptually similar as both are negative emotional states. We would like to point out, however, that we defined and operationalized anxiety as the experience of anxiety as a general emotional state during the pandemic, rather than the specific anxiety about COVID-19. In other words, people may experience anxiety during the pandemic, partly because of COVID-19 but also because of other factors. In comparison, worry was defined as an emotional dimension of risk perception and reflected people’s emotional reactions specifically about getting COVID-19. As such, the worry element of risk perception is viewed as an antecedent of anxiety during the pandemic, and the purpose of our study was to try to understand the extent to which the risk perception about COVID-19 made people feel anxious during the pandemic.

In the study context, due to the sudden outbreak of the pandemic and the lockdown which interrupted shipments and prevented workers to return to factories, there was a severe shortage of protective equipment (PPE) in China in early 2020 (Burki, 2020). At the time when we collected data in China in March and April 2020, the PPE shortage was gradually improved due to the massive production of PPE and reopening of factories with some safety measures introduced to account for PPE shortages. For instance, to preserve the stock of masks in case of short supply, employees were asked to properly sanitize their masks.

Although our discussions focus on COVID-19 specific safety performance, anxiety may interfere with other aspects of work performance through similar mechanisms. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for pointing this out.

For exploratory purposes, we conducted Steiger’s (1980) z test to compare the anxiety-safety compliance correlation (r = -.35, p = 0.00) and the anxiety-safety citizenship behavior correlation (r = -.24, p = 0.00). We found that anxiety correlated more strongly and negatively with safety compliance than safety citizenship behaviors (z = -2.70, p = 0.00) to provide some preliminary evidence regarding this issue. This finding suggested that it would be difficult for anxious employees to comply with the safety requirements on the job but that carrying out safety citizenship behaviors was probably not as difficult compared to complying with safety rules. One explanation may be that, unlike safety compliance which is required and reinforced at work during the pandemic, safety citizenship behaviors are more voluntary, and it may not be as stressful and hence not resource depleting to carry out safety citizenship compared to complying with safety rules. We would also like to note that this result was exploratory as Steiger’s (1980) z test was intended for comparing between the correlation coefficients but not between the suppression effects which were based on multilevel modeling.

Results reported in subsequent sections were based on the full scale of anxiety, but we conducted all focal analyses again without the three reverse-worded items to validate the results. Results showed that none of the path coefficients changed significance after excluding these reverse-worded items. Therefore, our substantive conclusions hold, with or without these negatively worded items. Detailed results after removing the reverse-coded items can be obtained from the first author.

We followed best-practice advice (Enders & Tofighi, 2007) to center team safety climate around the grand mean. As such, results based on this unit-level variable should be interpreted relative to the mean score across units. We also centered individual-level moderators, including COVID-19 risk perception and abusive supervision, around their group means such that the cross-level interactions are not distorted by between-unit variance in these individual-level moderators.

References

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. London, UK: Sage.

Beus, J. M., McCord, M. A., & Zohar, D. (2016). Workplace safety: A review and research synthesis. Organizational Psychology Review, 6(4), 352–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386615626243

Bishop, S. J., Duncan, J., Brett, M., & Lawrence, A. D. (2004). Prefrontal cortical function and anxiety: Controlling attention to threat-related stimuli. Nature Neuroscience, 7(2), 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1173

Bliese, P. D. (1998). Group size, ICC values, and group-level correlations: A simulation. Organizational Research Methods, 1(4), 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814001

Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., McCaul, K. D., & Weinstein, N. D. (2007). Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychology, 26(2), 136–145.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Brown, T. A. (2015). Methodology in the social sciences: Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Burki, T. (2020). Global shortage of personal protective equipment. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(7), 785–786.

Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367–383.

Christian, M. S., Bradley, J. C., Wallace, J. C., & Burke, M. J. (2009). Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1103–1127. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016172

Courtright, S. H., Colbert, A. E., & Choi, D. (2014). Fired up or burned out? How developmental challenge differentially impacts leader behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 681–696.

Daniels, K., Brough, P., Guppy, A., Peters-Bean, K. M., & Weatherstone, L. (1997). A note on modification to Warr’s measures of affective well-being at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70, 129–138.

Dryhurst, S., Schneider, C. R., Kerr, J., Freeman, A. L., Recchia, G., van der Bles, A. M., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. Journal of Risk Research, 23, 994–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.202.1758193

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

Eysenck, M. W. (1997). Anxiety and cognition: A unified theory. Erlbaum, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Fischer, T., Tian, A. W., Lee, A., & Hughes, D. J. (2021). Abusive supervision: a systematic review and fundamental rethink. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(6), 101540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101540

Fox, E., Russo, R., & Georgiou, G. A. (2005). Anxiety modulates the degree of attentive resources required to process emotional faces. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 5(4), 396–404. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.5.4.396

Griffin, M. A., & Neal, A. (2000). Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.3.347

Gyekye, A. S., & Haybatollahi, M. (2014). Relationship between organizational justice and organizational safety climate: do fairness perceptions influence employee safety behaviour. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 20(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2014.11077045

He, Y., Wang, Y., & Payne, S. C. (2019). How is safety climate formed? A meta-analysis of the antecedents of safety climate. Organizational Psychology Review, 9(2-3), 124–156.

Hofmann, D. A., Morgeson, F. P., & Gerras, S. J. (2003). Climate as a moderator of the relationship between leader-member exchange and content specific citizenship: Safety climate as an exemplar. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 170–178.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, Y.-H., Lee, J., Chen, Z., Perry, M., Cheung, J. H., & Wang, M. (2017). An item-response theory approach to safety climate measurement: The Liberty Mutual Safety Climate Short Scales. Accident; Analysis and Prevention, 103, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2017.03.015

Imai, K., Keele, L., & Tingley, D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 15, 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020761

James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1984). Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of applied psychology, 69(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-901.69.1.85

Kaptein, A. A., van Korlaar, I. M., Cameron, L. D., Vossen, C. Y., van der Meer, F. J. M., & Rosendaal, F. R. (2007). Using the common-sense model to predict risk perception and disease-related worry in individuals at increased risk for venous thrombosis. Health Psychology, 26(6), 807–812. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.807

LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 267–286. 1.1037/0033–2909.127.2.267

MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026595011371

Mata, R., Josef, A. K., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., & Hertwig, R. (2011). Age differences in risky choice: a meta-analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1235, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.0620.x

Meyer, R. D., Dalal, R. S., & Hermida, R. (2010). A review and synthesis of situational strength in the organizational sciences. Journal of Management, 36(1), 121–140.

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1159

Morrow, P. C., & Crum, M. R. (1998). The effects of perceived and objective safety risk on employee outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 53(2), 300–313. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1997.1620

Murray, M., & McMillan, C. (1993). Health beliefs, locus of control, emotional control and women's cancer screening behaviour. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 32(1), 87–100.

Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021484

Neal, A., & Griffin, M. A. (2004). Safety climate and safety at work. In J. Barling & M. R. Frone (Eds.), The psychology of workplace safety (pp. 15–34). American Psychological Association.

Nielsen, M. B., Skogstad, A., Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2016). The importance of a multidimensional and temporal design in research on leadership and workplace safety. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 142–155.

Nye, C. D., & Drasgow, F. (2011). Assessing Goodness of Fit: Simple Rules of Thumb Simply Do Not Work. Organizational Research Methods, 14(3), 548–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110368562

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). (2020). Guidance on preparing workplaces for COVID-19 (OSHA 3990-03 2020). Retrieved online on July 17, 2020 at: https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/OSHA3990.pdf

Pauley, K. A., O’Hare, D., Mullen, N. W., & Wiggins, M. (2008). Implicit perceptions of risk and anxiety and pilot involvement in hazardous events. Human Factors, 50(5), 723–733. https://doi.org/10.1518/001872008X312350

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team (2022). nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1-155, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Richards, D. A., & Schat, A. C. (2011). Attachment at (not to) work: applying attachment theory to explain individual behavior in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020372

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. DOI: https://hdl.handle.net/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rudolph, C. W., Allan, B., Clark, M., Hertel, G., Hirschi, A., Kunze, F., ... & Zacher, H. (2021). Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(1-2), 1–35.

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(3), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.3.513

Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology, 57(1), 1–29.

Sheeran, P., Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2014). Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychological Bulletin, 140(2), 511–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033065

Shiloh, S., Wade, C. H., Roberts, J. S., Alford, S. H., & Biesecker, B. B. (2013). Associations between risk perceptions and worry about common diseases: a between- and within-subjects examination. Psychology & Health, 28(4), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2012.737464

Sinclair, R. R., Allen, T., Barber, L., Bergman, M., Britt, T., Butler, A., ... & Yuan, Z. (2020). Occupational health science in the time of COVID-19: Now more than ever. Occupational Health Science, 4(1), 1–22.

Sitkin, S. B., & Pablo, A. L. (1992). Reconceptualizing the determinants of risk behavior. Academy of Management Review, 17(1), 9–38. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1992.4279564

Sjöberg, L. (1998). Worry and risk perception. Risk Analysis, 18, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb00918.x

Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2007). The affect heuristic. European journal of operational research, 177(3), 1333–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2005.04.006

Steiger, J. H. (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87(2), 245–251.

Taylor, W. D., & Snyder, L. A. (2017). The influence of risk perception on safety: A laboratory study. Safety Science, 95, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.02.011

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–19. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556375

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Hoobler, J., & Ensley, M. D. (2004). Moderators of the relationships between coworkers’ organizational citizenship behavior and fellow employees’ attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 455–465. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-901.89.3.455

Timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic. (2021, March 8). In Wikipedia. Retrieved online November 3, 2021 at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_COVID-19_pandemic

Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L., & Imai, K. (2014). Mediation R package for causal mediation analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 59, 16414. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v059.i05

Turner, M. M., Rimal, R. N., Morrison, D., & Kim, H. (2006). The role of anxiety in seeking and retaining risk information: Testing the risk perception attitude framework in two studies. Human Communication Research, 32(2), 130–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2006.00006.x

US Centers of Disease Control. (2021, March 11). Workplaces and businesses: Plan, prepare, and respond. Retrieved online November 11, 2021 at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/workplaces-businesses/index.html

van Bavel, J. J., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., & Drury, J. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behavior, 4, 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

van der Linden, S. (2015). The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.11.012

Weinstein, N. D. (2000). Perceived probability, perceived severity, and health-protective behavior. Health Psychology, 19(1), 65–74. 1.1037/0278–6133.19.1.65

Wells, J. D., Hobfoll, S. E., & Lavin, J. (1999). When it rains, it pours: The greater impact of resource loss compared to gain on psychological distress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(9), 1172–1182. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672992512010

Whitman, M. V., Halbesleben, J. R., & Holmes, O., IV. (2014). Abusive supervision and feedback avoidance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1852

World Health Organization. (2021, January 22). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved online November 11, 2021 at: https://covid19.who.int

Xia, N., Wang, X., Griffin, M. A., Wu, C., & Liu, B. (2017). Do we see how they perceive risk? An integrated analysis of risk perception and its effect on workplace safety behavior. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 106, 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2017.06.010

Yang, L. Q., Zheng, X., Liu, X., Lu, C. Q., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2020). Abusive supervision, thwarted belongingness, and workplace safety: A group engagement perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(3), 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000436

Zohar, D. (2003). Safety climate: Conceptual and measurement issues. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 123–142). American Psychological Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., He, Y., Sheng, Z. et al. When Does Safety Climate Help? A Multilevel Study of COVID-19 Risky Decision Making and Safety Performance in the Context of Business Reopening. J Bus Psychol 37, 1313–1327 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09805-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09805-3