Abstract

The international corporate tax system is considered a network. Just like for transportation, “shortest” paths are computed, which minimize tax payments for multinational enterprises when they repatriate profits. We include corporate income tax rates, withholding taxes on dividends, double tax treaties, and double taxation relief methods. We find that treaty shopping leads to an average potential reduction of the tax burden on repatriated dividends of about 6% points. An indicator for centrality in the tax network identifies the UK, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands as the most important conduit countries. Low-tax havens do not have a crucial role in reducing dividend repatriation taxes. By contrast, tax haven financial centres do. In the regressions we find that the centrality measures are robustly significant explanatory variables for bilateral FDI stocks. This also holds for our treaty shopping indicator.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Preventing the Granting of Treaty Benefits in Inappropriate Circumstances, BEPS Action 6—2015 Final Report.

An early paper of Gerard and Gillard (2004) applies a related approach to only three countries.

We do use the withholding tax rates on royalties as explanatory variables in the regressions. Due to the strong correlation between the withholding tax rates for royalties and interest, we only include the former.

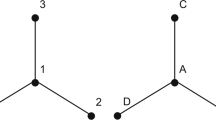

For further discussion of the network algorithm and its tax application, see Appendix C1.

Thus no-relief-at-all, which does occur sparingly, is ignored.

With an indirect tax credit both the host corporate income tax and the withholding tax are credited. With a direct tax credit only the withholding tax can be credited. We ignore the latter.

Altshuler and Grubert (2002) also use the term ‘repatriation tax’. They analyse the repatriation decision, which we take as given.

Alternative approaches are discussed in Appendix C1.

Given that the undiverted investment also would have taken place without the treaty shopping, this implies that the host country loses tax revenue. This is usually the case, and the OECD concludes that treaty shopping is a harmful tax practice (OECD 1998). IMF (2014) warns that treaty shopping is particularly harmful for developing countries.

See, for instance, Minieka (1978).

For a simple network that has ten countries and is complete, meaning that all direct pairwise connections exist, there are almost 10 million simple routes.

In an alternative exercise, in collaboration with the OECD, bilateral weights were constructed based on sparsely available but reported bilateral dividend flows and FDI stocks; see Van ‘t Riet et al. (2015).

World Bank Atlas method, based on 2013 GNI per capita data.

We have ignored lowest tax rates which only apply to non-profit organizations, such as pension funds and government institutions.

OECD Tax Database and KPMG Tax Tools and Resources.

The number refers to treaties where at least one of the bilateral withholding tax rates has been reduced.

European Union (1990). Next to the 27 EU member countries in 2013, also Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland are included.

World average taxation equals 1 − (1 − 0.17)(1 − 0.29) ≅ 0.41.

An example of a tax inversion was the planned 160 billion USD merger of the pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and Allergan, announced in November 2015. Pfizer is American but the legal residence of Allergan is in Ireland, which is also where the new company was supposed to reside. Measures in April 2016 taken by the US Treasury made the tax benefits of the merger uncertain and the merger plan was abandoned. US tax reform plans in 2017 would remove the tax incentive for inversion.

0.475 = 1 − (1 − 0.30) * (1 − 0.25).

0.188 = (0.391 − 0.25)/(1 − 0.25); see Sect. 3 for the formula of this tax rate.

The EU’s Parent–Subsidiary directive alone is responsible for (27 + 3) * (27 + 3 − 1) = 870 zero cells.

Luxembourg and the Netherlands are attractive for other tax reasons too. Liquidation of a company in Luxembourg is treated as a capital transaction and is not subject to a dividend withholding tax. The Netherlands has a general rate of zero on royalties and interest. Such characteristics have not been taken into account in the analysis. To avoid arbitrariness we stick to the bare tax parameters.

We take the ranking with range = 0.005 and penalty = 0.00499 as reference. Experimental rankings were generated with a higher range (0.05, 0.0499) and with a lower penalty (0.005, 0.002). These rankings yield Kendall’s (tau) correlation coefficients of 0.918 and 0.934, respectively.

Kendall’s (tau) rank correlation coefficients with BTWNS are 0.85 for OCCUR, 0.83 for STRCT and 0.82 for UNWTD.

This analysis builds upon a huge empirical literature on macro-FDI and taxation. See for some surveys De Mooij and Ederveen (2003) and Feld and Heckemeyer (2011). Besides there are various papers estimating the effect of bilateral tax treaties on FDI (Blonigen and Davies 2004, 2005; Egger et al. 2006; Sauvant and Sachs 2009; Blonigen et al. 2014).

See the definition of SPEs in Sect. 1.

We have used the average of the six governance indicators for this purpose.

Our empirical specification resembles Hong (2017). He also uses an OLS estimator in a cross section with the same geographic variables. We add the level of institutional quality and add more tax variables, such as the withholding tax rates on royalties and the bilateral withholding tax rate on dividends. Moreover, we combine the bilateral gains from treaty shopping and the centrality indicators in one specification. Another difference is our choice of using 2013 IMF/CDIS data, inclusive of SPEs, whereas Hong (2017) primarily uses 2012 UNCTAD data.

Many of these bilateral FDI stocks have the USA, Luxembourg, or the Netherlands as resident or host country. This corresponds to the ordering of aggregated inward and outward FDI stocks in Table 1.

Statistics and results for the non-tax variables, other than GDP, are presented in Appendix D1.

The results are available upon request. We have also eliminated BWHT and RCIT. Then the coefficient for GAIN is − 2.721 and statistically significant.

After correcting for missing values for GDP, institutions, and geographic variables, we have 10609 observations in the full sample. 4187 observations do not have a value for the bilateral FDI stock (about 40%). 1902 observations have a zero value for the FDI stock (18%). In the smaller OECD sample we miss 719 observations of the possible 3502 observations which is 20%. The number of zero values for FDI is 484, 14% of the total.

We use in the main regressions the network centrality indicator Betweenness which is double GDP-weighted. The weighting involves all bilateral flows except those with the country concerned as a starting or endpoint. Therefore, own GDP is not part of the measure and there is no endogeneity problem.

See, for instance, Minieka (1978).

This is the commutative property.

Strictly speaking it is not a metric, since, for instance, the property of symmetry is not satisfied.

This is the indirect tax credit system; see below.

Specifically, the world average CIT excludes the one of the countries under consideration.

References

Altshuler, R., & Grubert, H. (2002). Repatriation taxes, repatriation strategies and multinational financial policy. Journal of Public Economics, 87(2002), 73–107.

Avi-Yonah, R. S., & Panayi, C. H. J. I. (2011). Rethinking treaty shopping: Lessons for the European Union. In M. Lang, P. Stone, J. Schuch, C. Staringer, A. Storck, & M. Zagler (Eds.), Tax treaties: Building bridges between law and economics (pp. 21–50). Amsterdam: IBFD.

Barrios, S., Huizinga, H., Laeven, L., & Nicodème, G. (2012). International taxation and multinational firm location decisions. Journal of Public Economics, 96(2012), 946–958.

Benassy-Quere, A., Coupet, M., & Mayer, T. (2007). Institutional determinants of foreign direct investment. The World Economy, 30(5), 764–782.

Blonigen, B. A., & Davies, R. B. (2004). The effects of bilateral tax treaties on U.S. FDI activity. International Tax and Public Finance, 11, 601–622.

Blonigen, B., & Davies, R. B. (2005). Do bilateral tax treaties promote foreign direct investment? In E. Kwan Choy & J. Harrigan (Eds.), Handbook of international trade: Economic and legal analysis of laws and institutions. New York: Blackwell.

Blonigen, B. A., Davies, R. A., Waddell, G. R., & Naugthon, H. T. (2007). FDI in space: Spatial autoregressive relationships in foreign direct investment. European Economic Review, 51, 1303–1325.

Blonigen, B. A., Oldenski, L., & Sly, N. (2014). The differential effects of bilateral tax treaties. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(2), 1–18.

Chisik, R., & Davies, R. B. (2004). Asymmetric FDI and tax-treaty bargaining: Theory and evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1119–1148.

Davies, R. B. (2004). Tax treaties and foreign direct investment: Potential versus performance. International Tax and Public Finance, 11, 775–802.

De Mooij, R. A., & Ederveen, S. (2003). Taxation and foreign direct investment: A synthesis of empirical research. International Tax and Public Finance, 10, 673–693.

Deloitte. (2013). Deloitte international tax source | Country guides and highlights.

Dharmapala, D., & Hines, J. R., Jr. (2009). Which countries become tax havens? Journal of Public Economics, 93, 1058–1068.

Dyreng, S. D., Lindsey, B. P., Markle, K. S., & Shackelford, D. A. (2015). The effect of tax and nontax country characteristics on the global equity supply chains of U.S. multinationals. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 59(2–3), 182–202.

Egger, P., Larch, M., Pfaffermayr, M., & Winner, H. (2006). The impact of endogenous tax treaties on foreign direct investment: Theory and evidence. Canadian Journal of Economics, 39(3), 901–931.

Egger, P., Loretz, S., Pfaffermayr, M., & Winner, H. (2009). Bilateral effective tax rates and foreign direct investment. International Tax and Public Finance, 16, 822–849.

European Union. (1990). Council Directive 90/435/EEC of 23 July 1990 on the common system of taxation applicable in the case of parent companies and subsidiaries of different Member States.

European Union. (2016). Council Directive (EU) 2016/1164 of 12 July 2016 laying down rules against tax avoidance practices that directly affect the functioning of the internal market (ATAD).

EY. (2013). Worldwide corporate tax guide 2013.

Feld, L. P., & Heckemeyer, J. (2011). FDI and taxation: A meta study. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(2), 233–272.

Gerard, M., & Gillard, M.-F. (2004). Taxation, financial intermodality and the least taxed path for circulating income within a multinational enterprise. Annales d’Economie et de Statistiques, 75/76, 89–107.

Gravelle, J. G. (2013). Tax havens: International tax avoidance and evasion. Congressional Research Service.

Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity equations workhorse toolkit and cookbook. In G. Gopinath, E. Helpman, & K. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of international economics (pp. 131–195). New York: Elsevier.

Hines, J. R., Jr., & Rice, E. M. (1994). Fiscal paradise: Foreign tax havens and American business. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 149–182.

Hong, S. (2017). Tax treaties and foreign direct investment: A network approach. International Tax and Public Finance (forthcoming).

IMF. (2014). Spillovers in international corporate taxation, IMF policy paper, May 9 2014.

Loyens & Loeff. (2013). Holding regimes 2013—Comparison of selected countries.

Minieka, E. (1978). Optimization algorithms for networks and graphs. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.

Mintz, J. M., & Weichenrieder, A. J. (2010). The indirect side of direct investment—Multinational company finance and taxation, CESifo Book Series.

OECD. (1998). Harmful tax competition: An emerging global issue.

OECD. (2013). Addressing base erosion and profit shifting.

OECD. (2015). Final BEPS package for reform of the international tax system to tackle tax avoidance.

Polak, S. (2015). Algorithms for the network analysis of bilateral tax treaties, Master Thesis University of Amsterdam, under supervision of Guido Schäfer, CWI Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica Amsterdam. https://esc.fnwi.uva.nl/thesis/centraal/files/f1020945453.pdf.

Santos-Silva, J. M. C., & Terenyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 641–658.

Sauvant, K. P., & Sachs, L. E. (Eds.). (2009). The effects of treaties on foreign direct investment: Bilateral investment treaties, double tax treaties, and investment flows. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van ‘t Riet, M., & Lejour, A. (2014). Ranking the stars; Network analysis of bilateral tax treaties. CPB discussion paper 290.

Van ‘t Riet, M., Lejour, A., & Hanappi, T. (2015). Network analysis of tax treaty shopping using dividend-based weights. CPB Notitie August 28, 2015.

Weyzig, F. (2013). Tax treaty shopping: Structural determinants of Foreign Direct Investment routed through the Netherlands. International Tax and Public Finance, 20(6), 910–937.

World Bank. (2016). Worldwide governance indicators.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Leon Bettendorf, Sijbren Cnossen, Egbert Jongen, Simon Loretz, Guido Schäfer, Eric Vermeulen, and Hendrik Vrijburg for helpful comments and feedback. Celine Azemar, Steven Brakman, Julia Braun, Marcel Gérard, Fuad Hasanov, David Saltzman, and Marcel Timmer are thanked for their discussions of our work. Moreover, we thank the participants of the Bank of Italy workshop in Perugia, ZEW Public Finance Conference in Mannheim, Economic Conference on International Taxation and Information Exchange in Mons, IIPF Conference in Dublin, and NTA Conference in Boston, all in 2015, and the IIPF conference in Tokyo 2017. Ali Aouragh, Arie ten Cate, Sara Delgado, and Sven Polak are thanked for programming and data compilation. We thank two anonymous referees and Ron Davies for their constructive comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A1: Collected tax data 2013—108 jurisdictions

Tax variable (unit) | CIT rate (%) | Relief method | Treaty relief method | CFC rule (dummy) | WHTdiv (%) | DTT (no.) | Tax haven (dummy) | GDP weight (% point) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

Albania | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 26 | 0 | 0.03 |

Algeria | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 23 | 0 | 0.34 |

Angola | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.16 |

Argentina | 35 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 14 | 0 | 0.94 |

Aruba | 28 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 |

Australia | 30 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 40 | 0 | 1.23 |

Austria | 25 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 25 | 66 | 0 | 0.45 |

Azerbaijan | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 29 | 0 | 0.12 |

Bahamas | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.01 |

Bahrain | 46 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0.04 |

Barbados | 25 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 23 | 1 | 0.01 |

Belarus | 18 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 44 | 0 | 0.19 |

Belgium | 34 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 25 | 70 | 0 | 0.53 |

Bermuda | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.01 |

Botswana | 22 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7.5 | 8 | 0 | 0.04 |

Brazil | 34 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 15 | 35 | 0 | 2.97 |

Brunei Darussalam | 20 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.03 |

Bulgaria | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 50 | 0 | 0.13 |

Canada | 26.3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 25 | 75 | 0 | 1.88 |

Cayman Islands | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 |

Chile | 20 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 24 | 0 | 0.40 |

China | 25 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 61 | 0 | 15.66 |

Colombia | 25 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0.63 |

Costa Rica | 30 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 0.07 |

Croatia | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 44 | 0 | 0.10 |

Curacao | 27.5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

Cyprus | 12.5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 1 | 0.03 |

Czech Republic | 19 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 66 | 0 | 0.36 |

Denmark | 25 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 27 | 61 | 0 | 0.27 |

Dominican Rep. | 29 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0.12 |

Ecuador | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0.19 |

Egypt | 25 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0.68 |

Equatorial Guinea | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 0.02 |

Estonia | 21 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 0.04 |

Finland | 24.5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 24.5 | 59 | 0 | 0.25 |

France | 34.3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 30 | 80 | 0 | 2.84 |

Gabon | 35 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 0.03 |

Germany | 30.2 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 25 | 71 | 0 | 4.04 |

Greece | 26 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 42 | 0 | 0.35 |

Guernsey | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 |

Hong Kong | 16.5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 0.47 |

Hungary | 19 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 47 | 0 | 0.25 |

Iceland | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 18 | 38 | 0 | 0.02 |

India | 34 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 5.91 |

Indonesia | 25 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 20 | 52 | 0 | 1.54 |

Ireland | 12.5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 20 | 53 | 1 | 0.24 |

Isle of Man | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.01 |

Israel | 25 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 20 | 43 | 0 | 0.31 |

Italy | 31.4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 20 | 69 | 0 | 2.31 |

Jamaica | 25 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 33.33 | 15 | 0 | 0.03 |

Japan | 37 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 47 | 0 | 5.84 |

Jersey | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.01 |

Jordan | 14 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0.05 |

Kazakhstan | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 35 | 0 | 0.29 |

Korea Republic | 24.2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 20 | 67 | 0 | 2.04 |

Kuwait | 15 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 15 | 40 | 0 | 0.19 |

Latvia | 15 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 45 | 0 | 0.05 |

Lebanon | 15 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 13 | 1 | 0.08 |

Libya | 20 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.10 |

Liechtenstein | 12.5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0.00 |

Lithuania | 15 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 44 | 0 | 0.08 |

Luxembourg | 29.2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 57 | 1 | 0.05 |

Macao | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.06 |

Malaysia | 25 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0.63 |

Malta | 35 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 1 | 0.01 |

Mauritius | 15 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 0.03 |

Mexico | 30 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 2.22 |

Mongolia | 25 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 20 | 27 | 0 | 0.02 |

Namibia | 34 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 9 | 0 | 0.02 |

Netherlands | 25 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 74 | 0 | 0.89 |

New Zealand | 28 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 36 | 0 | 0.17 |

Nigeria | 30 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 0.57 |

Norway | 28 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 25 | 64 | 0 | 0.35 |

Oman | 12 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0.11 |

Pakistan | 35 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 31 | 0 | 0.65 |

Panama | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 14 | 1 | 0.07 |

Peru | 30 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4.1 | 3 | 0 | 0.41 |

Philippines | 30 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 29 | 0 | 0.54 |

Poland | 19 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 19 | 64 | 0 | 1.01 |

Portugal | 31.5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 25 | 53 | 0 | 0.31 |

Puerto Rico | 30 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 |

Qatar | 10 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 36 | 0 | 0.24 |

Romania | 16 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 66 | 0 | 0.35 |

Russian Federation | 20 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 59 | 0 | 3.17 |

Saudi Arabia | 20 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 18 | 0 | 1.14 |

Serbia and Mont. | 15 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 20 | 42 | 0 | 0.10 |

Seychelles | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 12 | 1 | 0.00 |

Singapore | 17 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 1 | 0.41 |

Slovak Republic | 23 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 0 | 0.17 |

Slovenia | 17 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 46 | 0 | 0.07 |

South Africa | 28 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 15 | 55 | 0 | 0.74 |

Spain | 30 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 21 | 71 | 0 | 1.78 |

Suriname | 36 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 0.01 |

Sweden | 22 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 67 | 0 | 0.50 |

Switzerland | 21.1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 35 | 71 | 1 | 0.46 |

Taiwan Province | 17 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 20 | 19 | 0 | 1.14 |

Thailand | 20 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 34 | 0 | 0.82 |

Trinidad and Tob. | 25 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 16 | 0 | 0.03 |

Tunisia | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 0.13 |

Turkey | 20 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 15 | 59 | 0 | 1.42 |

Ukraine | 19 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 56 | 0 | 0.42 |

United Arab Emirates | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0.34 |

UK | 23 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 51 | 0 | 2.95 |

USA | 39.1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 54 | 0 | 19.79 |

Uruguay | 25 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0.07 |

Venezuela | 34 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 34 | 28 | 0 | 0.51 |

Virgin Islands USA | 38.5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 |

Virgin Islands UK | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 |

Appendix A2: Tax havens

The first three columns give the intersection of the Gravelle (2013) list of 50 tax havens with our selection of 108 jurisdictions. The first column presents the low-tax havens, i.e. those with a corporate income tax rate in 2013 of 12.5% or less. Most of them are islands. Malta could have been included in the list of low-tax havens because the effective rate may be reduced to 10% or even less by a refund mechanism, although it has a nominal rate of 35% (Loyens and Loeff 2013). We refrain from using such characteristics and stick to the bare tax parameters (Table 14).

The second column indicates the five countries from the Gravelle list that we have treated differently with respect to the CFC rules. We believe these five countries are not subjected to the same anti-abuse scrutiny as are the jurisdictions in the first and third column. The Gravelle list is based on an overview of other papers classifying tax havens. The first four appear only in the list of Dharmapala and Hines (2009) and Hines and Rice (1994), and Singapore is often considered as another financial centre, different from other tax havens (OECD “grey” list).

The third column contains the other tax havens in our analysis that are deprived of preferential tax relief by those countries indicated to apply CFC rules. These are neither low-tax havens nor financial centres. The fourth column contains, for comparison, the other countries in the country set with a low tax rate, i.e. a CIT of 12.5% or less.

Appendix B1: Average dividend repatriation for home countries

Tax variables (unit) | Avg. BWHT inward (%) | Direct routes (%) | Optimal routes (%) | Gain TS (%) | Rank optimal (no.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Albania | 13.72 | 13.76 | 1.64 | 12.12 | 29 |

Algeria | 13.35 | 35.01 | 26.23 | 8.78 | 103 |

Angola | 17.39 | 46.31 | 36.06 | 10.25 | 107 |

Argentina | 14.76 | 17.83 | 8.19 | 9.65 | 90 |

Aruba | 17.38 | 17.38 | 1.64 | 15.74 | 12 |

Australia | 6.38 | 8.01 | 1.77 | 6.24 | 78 |

Austria | 4.82 | 4.82 | 1.65 | 3.17 | 58 |

Azerbaijan | 13.93 | 14.08 | 1.63 | 12.45 | 10 |

Bahamas | 17.39 | 17.39 | 1.64 | 15.75 | 22 |

Bahrain | 15.35 | 27.11 | 23.26 | 3.86 | 98 |

Barbados | 9.87 | 10.27 | 1.64 | 8.63 | 21 |

Belarus | 9.96 | 10.09 | 1.64 | 8.45 | 43 |

Belgium | 4.28 | 5.56 | 1.65 | 3.91 | 62 |

Bermuda | 17.38 | 17.38 | 1.64 | 15.75 | 14 |

Botswana | 16.56 | 34.92 | 23.28 | 11.64 | 99 |

Brazil | 15.08 | 17.84 | 7.20 | 10.64 | 88 |

Brunei Darussalam | 16.60 | 16.60 | 1.64 | 14.97 | 26 |

Bulgaria | 6.69 | 6.72 | 1.64 | 5.08 | 40 |

Canada | 6.25 | 6.40 | 1.57 | 4.83 | 5 |

Cayman Islands | 17.38 | 17.38 | 1.64 | 15.74 | 15 |

Chile | 14.71 | 26.60 | 1.62 | 24.98 | 7 |

China | 7.74 | 8.59 | 1.01 | 7.58 | 1 |

Colombia | 16.44 | 16.88 | 1.65 | 15.23 | 64 |

Costa Rica | 17.10 | 41.46 | 6.55 | 34.91 | 84 |

Croatia | 11.74 | 11.94 | 1.64 | 10.30 | 38 |

Curacao | 17.38 | 17.38 | 1.64 | 15.74 | 16 |

Cyprus | 7.52 | 7.52 | 1.64 | 5.88 | 27 |

Czech Republic | 5.41 | 6.70 | 1.64 | 5.06 | 55 |

Denmark | 4.20 | 4.58 | 1.64 | 2.94 | 48 |

Dominican Rep. | 17.26 | 18.12 | 1.63 | 16.50 | 8 |

Ecuador | 15.27 | 33.91 | 23.28 | 10.63 | 100 |

Egypt | 9.71 | 17.85 | 1.65 | 16.20 | 65 |

Equatorial Guinea | 17.38 | 46.30 | 36.06 | 10.24 | 108 |

Estonia | 6.56 | 6.72 | 1.64 | 5.08 | 30 |

Finland | 3.38 | 3.65 | 1.64 | 2.01 | 46 |

France | 3.29 | 4.91 | 1.69 | 3.23 | 74 |

Gabon | 16.71 | 44.29 | 16.30 | 27.99 | 96 |

Germany | 4.66 | 6.08 | 1.71 | 4.37 | 76 |

Greece | 11.29 | 11.75 | 1.64 | 10.11 | 53 |

Guernsey | 17.38 | 17.38 | 1.64 | 15.74 | 17 |

Hong Kong | 13.80 | 13.80 | 1.65 | 12.15 | 60 |

Hungary | 5.63 | 5.79 | 1.64 | 4.15 | 47 |

Iceland | 6.42 | 6.56 | 1.64 | 4.92 | 23 |

India | 10.56 | 13.57 | 7.56 | 6.01 | 89 |

Indonesia | 9.23 | 9.64 | 1.66 | 7.97 | 71 |

Ireland | 5.53 | 5.58 | 1.64 | 3.94 | 45 |

Isle of Man | 17.38 | 17.38 | 1.64 | 15.75 | 18 |

Israel | 9.54 | 10.17 | 1.64 | 8.53 | 50 |

Italy | 5.56 | 7.00 | 1.68 | 5.32 | 73 |

Jamaica | 10.23 | 20.30 | 1.64 | 18.66 | 31 |

Japan | 5.99 | 7.73 | 3.56 | 4.17 | 82 |

Jersey | 17.38 | 17.38 | 1.64 | 15.75 | 19 |

Jordan | 15.42 | 25.30 | 6.56 | 18.74 | 85 |

Kazakhstan | 7.51 | 7.67 | 1.63 | 6.04 | 9 |

Korea Republic | 6.66 | 7.10 | 1.57 | 5.53 | 3 |

Kuwait | 12.05 | 25.24 | 16.40 | 8.85 | 97 |

Latvia | 6.24 | 6.31 | 1.64 | 4.67 | 33 |

Lebanon | 17.39 | 28.82 | 1.64 | 27.18 | 36 |

Libya | 17.36 | 33.81 | 6.56 | 27.25 | 86 |

Liechtenstein | 16.32 | 16.32 | 1.64 | 14.68 | 20 |

Lithuania | 6.25 | 6.31 | 1.64 | 4.67 | 37 |

Luxembourg | 4.03 | 4.03 | 1.64 | 2.39 | 34 |

Macao | 17.39 | 27.31 | 13.44 | 13.86 | 94 |

Malaysia | 11.81 | 11.81 | 1.65 | 10.16 | 63 |

Malta | 6.59 | 6.59 | 1.64 | 4.95 | 24 |

Mauritius | 14.78 | 14.86 | 1.64 | 13.22 | 28 |

Mexico | 4.12 | 32.88 | 31.10 | 1.78 | 104 |

Mongolia | 13.30 | 23.59 | 1.64 | 21.95 | 25 |

Namibia | 15.55 | 18.10 | 6.99 | 11.11 | 87 |

Netherlands | 3.39 | 3.39 | 1.65 | 1.74 | 67 |

New Zealand | 8.46 | 9.46 | 1.64 | 7.82 | 41 |

Nigeria | 16.06 | 17.07 | 1.78 | 15.30 | 79 |

Norway | 7.01 | 7.77 | 1.64 | 6.12 | 54 |

Oman | 16.11 | 16.16 | 1.64 | 14.52 | 39 |

Pakistan | 10.68 | 13.89 | 8.27 | 5.63 | 91 |

Panama | 15.56 | 36.67 | 26.23 | 10.44 | 101 |

Peru | 16.61 | 17.76 | 1.79 | 15.97 | 80 |

Philippines | 11.49 | 12.57 | 1.76 | 10.81 | 77 |

Poland | 6.26 | 6.29 | 1.66 | 4.64 | 68 |

Portugal | 8.51 | 9.66 | 1.64 | 8.01 | 49 |

Puerto Rico | 17.39 | 18.38 | 1.80 | 16.58 | 81 |

Qatar | 14.59 | 20.20 | 1.64 | 18.55 | 44 |

Romania | 7.46 | 7.54 | 1.64 | 5.89 | 51 |

Russian Federation | 6.49 | 6.68 | 1.53 | 5.15 | 2 |

Saudi Arabia | 12.96 | 22.62 | 1.66 | 20.96 | 70 |

Serbia and Mont. | 13.04 | 13.12 | 1.64 | 11.48 | 11 |

Seychelles | 16.35 | 43.96 | 34.10 | 9.86 | 106 |

Singapore | 10.84 | 10.84 | 1.65 | 9.19 | 56 |

Slovak Republic | 5.60 | 13.05 | 1.64 | 11.41 | 42 |

Slovenia | 6.42 | 6.51 | 1.64 | 4.87 | 35 |

South Africa | 5.44 | 6.63 | 1.65 | 4.98 | 66 |

Spain | 6.50 | 6.76 | 1.67 | 5.09 | 72 |

Suriname | 17.38 | 20.69 | 9.77 | 10.91 | 92 |

Sweden | 3.48 | 3.83 | 1.65 | 2.18 | 61 |

Switzerland | 4.92 | 4.92 | 1.65 | 3.27 | 59 |

Taiwan Province | 14.95 | 15.18 | 1.66 | 13.52 | 69 |

Thailand | 10.00 | 18.47 | 1.57 | 16.90 | 4 |

Trinidad and Tob. | 9.56 | 9.96 | 1.64 | 8.32 | 32 |

Tunisia | 11.44 | 38.01 | 31.15 | 6.86 | 105 |

Turkey | 10.58 | 10.91 | 1.59 | 9.32 | 6 |

Ukraine | 6.24 | 6.37 | 1.65 | 4.73 | 57 |

United Arab Emirates | 13.19 | 13.19 | 1.64 | 11.54 | 52 |

UK | 3.75 | 3.75 | 1.69 | 2.06 | 75 |

USA | 6.29 | 16.67 | 14.61 | 2.06 | 95 |

Uruguay | 16.05 | 37.04 | 26.23 | 10.81 | 102 |

Venezuela | 7.95 | 10.86 | 6.49 | 4.37 | 83 |

Virgin Islands USA | 17.38 | 22.18 | 13.23 | 8.95 | 93 |

Virgin Islands UK | 17.38 | 17.38 | 1.64 | 15.74 | 13 |

Appendix B2: Average dividend repatriation tax rates for host countries

Tax variables (unit) | Avg. BWHT outward (%) | Min. BWHT outward (%) | Direct routes (%) | Optimal routes (%) | Gain TS (%) | Rank optimal (no.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Albania | 9.00 | 0 | 19.91 | 5.40 | 14.51 | 45 |

Algeria | 11.67 | 0 | 13.99 | 5.34 | 8.66 | 22 |

Angola | 10.00 | 10 | 11.72 | 10.88 | 0.83 | 98 |

Argentina | 30.42 | 10 | 31.73 | 14.84 | 16.89 | 104 |

Aruba | 9.96 | 5 | 28.53 | 10.04 | 18.48 | 89 |

Australia | 10.77 | 0 | 15.14 | 4.69 | 10.45 | 13 |

Austria | 6.79 | 0 | 11.26 | 5.42 | 5.84 | 70 |

Azerbaijan | 9.58 | 5 | 15.29 | 10.13 | 5.16 | 92 |

Bahamas | 0.00 | 0 | 26.37 | 5.40 | 20.98 | 39 |

Bahrain | 0.00 | 0 | 20.57 | 4.89 | 15.67 | 16 |

Barbados | 9.78 | 0 | 28.77 | 5.40 | 23.37 | 38 |

Belarus | 10.05 | 0 | 15.60 | 5.41 | 10.20 | 57 |

Belgium | 6.19 | 0 | 9.10 | 3.46 | 5.64 | 6 |

Bermuda | 0.00 | 0 | 26.37 | 5.40 | 20.97 | 35 |

Botswana | 7.29 | 5 | 13.29 | 10.12 | 3.16 | 90 |

Brazil | 7.01 | 0 | 8.71 | 4.61 | 4.10 | 11 |

Brunei Darussalam | 0.00 | 0 | 11.21 | 5.40 | 5.81 | 43 |

Bulgaria | 4.00 | 0 | 17.46 | 5.40 | 12.06 | 55 |

Canada | 8.76 | 5 | 12.93 | 9.48 | 3.44 | 86 |

Cayman Islands | 0.00 | 0 | 26.37 | 5.40 | 20.97 | 30 |

Chile | 27.86 | 0 | 29.58 | 10.15 | 19.43 | 94 |

China | 9.41 | 5 | 13.77 | 10.70 | 3.07 | 97 |

Colombia | 0.00 | 0 | 7.70 | 5.43 | 2.28 | 75 |

Costa Rica | 14.83 | 5 | 32.41 | 19.16 | 13.25 | 107 |

Croatia | 8.63 | 0 | 13.75 | 5.40 | 8.34 | 53 |

Curacao | 0.00 | 0 | 6.65 | 5.31 | 1.33 | 21 |

Cyprus | 0.00 | 0 | 19.93 | 5.40 | 14.54 | 44 |

Czech Republic | 7.50 | 0 | 14.37 | 5.42 | 8.95 | 67 |

Denmark | 7.24 | 0 | 12.71 | 5.41 | 7.30 | 62 |

Dominican Rep. | 10.00 | 10 | 12.72 | 11.89 | 0.83 | 100 |

Ecuador | 0.00 | 0 | 9.67 | 5.37 | 4.30 | 23 |

Egypt | 0.00 | 0 | 7.56 | 5.43 | 2.13 | 76 |

Equatorial Guinea | 25.00 | 15 | 26.45 | 25.76 | 0.69 | 108 |

Estonia | 0.00 | 0 | 10.07 | 5.40 | 4.67 | 48 |

Finland | 5.87 | 0 | 11.69 | 5.41 | 6.28 | 61 |

France | 5.23 | 0 | 8.07 | 3.41 | 4.65 | 4 |

Gabon | 15.00 | 15 | 16.65 | 15.87 | 0.78 | 106 |

Germany | 8.11 | 0 | 11.18 | 4.76 | 6.42 | 14 |

Greece | 6.72 | 0 | 9.91 | 5.42 | 4.49 | 66 |

Guernsey | 0.00 | 0 | 26.37 | 5.40 | 20.97 | 31 |

Hong Kong | 0.00 | 0 | 23.37 | 5.42 | 17.95 | 72 |

Hungary | 0.00 | 0 | 11.35 | 5.41 | 5.94 | 60 |

Iceland | 7.66 | 0 | 14.06 | 5.40 | 8.66 | 40 |

India | 0.00 | 0 | 3.86 | 2.97 | 0.88 | 3 |

Indonesia | 11.05 | 0 | 14.54 | 5.48 | 9.06 | 81 |

Ireland | 2.66 | 0 | 16.20 | 5.41 | 10.79 | 59 |

Isle of Man | 0.00 | 0 | 26.37 | 5.40 | 20.97 | 32 |

Israel | 12.24 | 0 | 14.76 | 5.41 | 9.35 | 63 |

Italy | 8.04 | 0 | 10.60 | 4.33 | 6.27 | 9 |

Jamaica | 20.06 | 0 | 23.36 | 5.40 | 17.96 | 46 |

Japan | 7.25 | 0 | 9.24 | 2.48 | 6.77 | 2 |

Jersey | 0.00 | 0 | 26.37 | 5.40 | 20.97 | 36 |

Jordan | 0.00 | 0 | 14.96 | 5.40 | 9.57 | 33 |

Kazakhstan | 8.56 | 5 | 15.04 | 10.14 | 4.90 | 93 |

Korea Republic | 8.89 | 0 | 12.21 | 9.95 | 2.26 | 87 |

Kuwait | 10.10 | 0 | 17.26 | 5.38 | 11.88 | 24 |

Latvia | 5.62 | 0 | 15.35 | 5.40 | 9.95 | 49 |

Lebanon | 9.47 | 0 | 29.30 | 5.40 | 23.90 | 51 |

Libya | 0.00 | 0 | 11.19 | 5.40 | 5.80 | 37 |

Liechtenstein | 0.00 | 0 | 24.15 | 5.40 | 18.75 | 34 |

Lithuania | 6.64 | 0 | 16.10 | 5.40 | 10.69 | 52 |

Luxembourg | 1.79 | 0 | 6.92 | 4.86 | 2.06 | 15 |

Macao | 0.00 | 0 | 24.26 | 5.39 | 18.86 | 27 |

Malaysia | 0.00 | 0 | 7.61 | 5.43 | 2.19 | 74 |

Malta | 0.00 | 0 | 16.89 | 4.90 | 11.99 | 17 |

Mauritius | 0.00 | 0 | 23.62 | 5.40 | 18.23 | 42 |

Mexico | 0.00 | 0 | 4.86 | 4.05 | 0.81 | 7 |

Mongolia | 13.73 | 0 | 15.14 | 5.40 | 9.74 | 41 |

Namibia | 9.49 | 5 | 11.25 | 7.64 | 3.61 | 85 |

Netherlands | 4.47 | 0 | 10.05 | 5.44 | 4.61 | 77 |

New Zealand | 12.90 | 0 | 17.80 | 5.19 | 12.61 | 18 |

Nigeria | 9.31 | 7.5 | 11.67 | 9.96 | 1.71 | 88 |

Norway | 10.64 | 0 | 11.94 | 5.20 | 6.74 | 19 |

Oman | 0.00 | 0 | 16.32 | 5.40 | 10.92 | 54 |

Pakistan | 8.12 | 3.75 | 10.27 | 6.79 | 3.48 | 83 |

Panama | 15.61 | 0 | 32.98 | 5.39 | 27.60 | 25 |

Peru | 4.10 | 4.1 | 8.12 | 7.30 | 0.82 | 84 |

Philippines | 13.04 | 10 | 14.52 | 12.60 | 1.92 | 102 |

Poland | 7.80 | 0 | 13.75 | 5.45 | 8.31 | 78 |

Portugal | 9.28 | 0 | 12.00 | 4.22 | 7.78 | 8 |

Puerto Rico | 10.00 | 10 | 12.44 | 11.61 | 0.83 | 99 |

Qatar | 6.13 | 0 | 19.15 | 5.41 | 13.74 | 58 |

Romania | 8.74 | 0 | 14.83 | 5.42 | 9.41 | 65 |

Russian Federation | 8.62 | 5 | 15.20 | 10.29 | 4.91 | 96 |

Saudi Arabia | 4.78 | 0 | 12.71 | 5.46 | 7.26 | 80 |

Serbia and Mont. | 13.04 | 5 | 18.75 | 10.13 | 8.62 | 91 |

Seychelles | 13.00 | 0 | 30.82 | 5.40 | 25.43 | 28 |

Singapore | 0.00 | 0 | 13.00 | 5.42 | 7.58 | 68 |

Slovak Republic | 0.00 | 0 | 8.79 | 5.41 | 3.39 | 56 |

Slovenia | 6.75 | 0 | 14.98 | 5.40 | 9.58 | 50 |

South Africa | 6.68 | 0 | 10.42 | 5.22 | 5.20 | 20 |

Spain | 7.84 | 0 | 9.88 | 4.69 | 5.19 | 12 |

Suriname | 24.86 | 7.5 | 26.32 | 12.49 | 13.83 | 101 |

Sweden | 5.97 | 0 | 12.50 | 5.42 | 7.08 | 73 |

Switzerland | 7.31 | 0 | 13.03 | 5.42 | 7.61 | 71 |

Taiwan Province | 17.71 | 0 | 21.29 | 5.46 | 15.83 | 79 |

Thailand | 10.00 | 10 | 15.56 | 14.70 | 0.86 | 103 |

Trinidad and Tob. | 8.95 | 0 | 12.95 | 5.40 | 7.55 | 47 |

Tunisia | 0.00 | 0 | 5.39 | 4.56 | 0.83 | 10 |

Turkey | 10.29 | 0 | 15.05 | 10.20 | 4.85 | 95 |

Ukraine | 7.14 | 0 | 14.19 | 5.42 | 8.77 | 69 |

United Arab Emirates | 0.00 | 0 | 22.59 | 5.41 | 17.18 | 64 |

UK | 0.00 | 0 | 8.92 | 5.55 | 3.37 | 82 |

USA | 10.26 | 0 | 11.99 | 2.20 | 9.79 | 1 |

Uruguay | 6.75 | 0 | 11.79 | 5.39 | 6.41 | 26 |

Venezuela | 14.12 | 0 | 16.03 | 3.44 | 12.59 | 5 |

Virgin Islands USA | 11.00 | 11 | 29.35 | 15.35 | 14.00 | 105 |

Virgin Islands UK | 0.00 | 0 | 26.37 | 5.40 | 20.97 | 29 |

Appendix B3: Centrality measures

BTWNS | OCCUR | STRCT | UNWTD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

% | Rank | % | Rank | % | Rank | % | Rank | |

Albania | 0.2 | 55 | 14.9 | 57 | 0.1 | 47 | 0.2 | 57 |

Algeria | 0.0 | 81 | 0.0 | 81 | 0.0 | 84 | 0.0 | 83 |

Angola | 0.0 | 74 | 0.0 | 82 | 0.0 | 85 | 0.0 | 84 |

Argentina | 0.0 | 75 | 0.0 | 83 | 0.0 | 86 | 0.0 | 85 |

Aruba | 0.0 | 73 | 0.0 | 84 | 0.0 | 87 | 0.0 | 74 |

Australia | 1.3 | 35 | 27.1 | 50 | 0.1 | 44 | 0.2 | 56 |

Austria | 2.1 | 22 | 46.8 | 26 | 0.6 | 25 | 3.0 | 18 |

Azerbaijan | 0.1 | 59 | 5.8 | 66 | 0.0 | 64 | 0.0 | 69 |

Bahamas | 0.8 | 41 | 35.7 | 46 | 0.0 | 53 | 2.1 | 30 |

Bahrain | 0.0 | 76 | 0.0 | 85 | 0.0 | 88 | 0.0 | 76 |

Barbados | 0.2 | 56 | 16.5 | 54 | 0.1 | 43 | 1.9 | 37 |

Belarus | 0.1 | 60 | 13.1 | 60 | 0.0 | 60 | 0.1 | 58 |

Belgium | 1.1 | 38 | 36.5 | 38 | 0.1 | 45 | 1.5 | 42 |

Bermuda | 0.8 | 42 | 35.8 | 40 | 0.0 | 54 | 2.1 | 31 |

Botswana | 0.0 | 77 | 0.0 | 86 | 0.0 | 89 | 0.0 | 86 |

Brazil | 0.1 | 61 | 3.4 | 77 | 0.0 | 74 | 0.1 | 65 |

Brunei Darussalam | 2.6 | 18 | 65.1 | 9 | 1.2 | 14 | 2.8 | 20 |

Bulgaria | 2.0 | 23 | 47.8 | 25 | 0.5 | 30 | 2.2 | 29 |

Canada | 0.1 | 62 | 5.8 | 67 | 0.1 | 48 | 0.2 | 55 |

Cayman Islands | 0.8 | 43 | 35.8 | 41 | 0.0 | 55 | 2.1 | 32 |

Chile | 0.0 | 78 | 7.0 | 65 | 0.0 | 71 | 0.0 | 78 |

China | 0.0 | 79 | 5.7 | 70 | 0.0 | 70 | 0.0 | 75 |

Colombia | 1.9 | 27 | 60.5 | 15 | 0.3 | 33 | 2.3 | 23 |

Costa Rica | 0.0 | 80 | 0.0 | 87 | 0.0 | 90 | 0.0 | 87 |

Croatia | 0.4 | 52 | 29.5 | 48 | 0.2 | 39 | 0.6 | 51 |

Curacao | 1.7 | 30 | 61.8 | 14 | 0.3 | 34 | 2.7 | 21 |

Cyprus | 4.5 | 10 | 59.2 | 17 | 1.8 | 10 | 8.1 | 3 |

Czech Republic | 1.4 | 33 | 41.3 | 32 | 0.2 | 35 | 1.4 | 45 |

Denmark | 4.0 | 13 | 55.4 | 19 | 1.1 | 15 | 2.2 | 25 |

Dominican Rep. | 0.1 | 63 | 5.8 | 68 | 0.0 | 77 | 0.0 | 71 |

Ecuador | 0.0 | 82 | 0.0 | 88 | 0.0 | 91 | 0.0 | 88 |

Egypt | 0.4 | 51 | 39.8 | 33 | 0.0 | 61 | 0.4 | 53 |

Equatorial Guinea | 0.0 | 84 | 0.0 | 89 | 0.0 | 92 | 0.0 | 89 |

Estonia | 6.7 | 4 | 76.0 | 3 | 3.1 | 5 | 6.3 | 7 |

Finland | 4.7 | 9 | 63.4 | 11 | 1.6 | 12 | 2.2 | 28 |

France | 1.5 | 32 | 36.4 | 39 | 0.5 | 31 | 2.2 | 27 |

Gabon | 0.0 | 83 | 0.0 | 90 | 0.0 | 93 | 0.0 | 90 |

Germany | 0.8 | 44 | 29.3 | 49 | 0.1 | 51 | 1.0 | 49 |

Greece | 1.7 | 31 | 45.2 | 28 | 0.4 | 32 | 1.4 | 46 |

Guernsey | 0.8 | 45 | 35.8 | 42 | 0.0 | 56 | 2.1 | 33 |

Hong Kong | 2.3 | 19 | 42.8 | 29 | 0.9 | 20 | 4.1 | 12 |

Hungary | 6.2 | 5 | 76.9 | 1 | 2.3 | 7 | 6.9 | 5 |

Iceland | 1.9 | 28 | 48.3 | 24 | 0.6 | 26 | 1.4 | 44 |

India | 0.3 | 53 | 2.6 | 78 | 0.1 | 46 | 0.3 | 54 |

Indonesia | 0.1 | 64 | 8.9 | 62 | 0.0 | 69 | 0.0 | 70 |

Ireland | 5.6 | 7 | 70.1 | 5 | 2.9 | 6 | 3.8 | 14 |

Isle of Man | 0.8 | 46 | 35.8 | 43 | 0.0 | 57 | 2.1 | 34 |

Israel | 0.1 | 65 | 9.8 | 61 | 0.0 | 68 | 0.1 | 62 |

Italy | 0.8 | 47 | 32.2 | 47 | 0.1 | 52 | 0.9 | 50 |

Jamaica | 0.0 | 85 | 4.3 | 74 | 0.0 | 72 | 0.1 | 63 |

Japan | 0.0 | 87 | 0.0 | 91 | 0.0 | 94 | 0.0 | 91 |

Jersey | 0.8 | 48 | 35.8 | 44 | 0.0 | 58 | 2.1 | 35 |

Jordan | 0.0 | 86 | 0.0 | 92 | 0.0 | 95 | 0.0 | 92 |

Kazakhstan | 0.1 | 66 | 5.8 | 69 | 0.0 | 62 | 0.0 | 79 |

Korea Republic | 0.1 | 67 | 7.4 | 63 | 0.0 | 66 | 0.0 | 66 |

Kuwait | 0.0 | 88 | 0.0 | 93 | 0.0 | 96 | 0.0 | 93 |

Latvia | 2.0 | 24 | 49.3 | 22 | 0.6 | 23 | 1.7 | 40 |

Lebanon | 0.0 | 89 | 0.1 | 79 | 0.0 | 97 | 0.0 | 80 |

Libya | 0.0 | 90 | 0.0 | 94 | 0.0 | 98 | 0.0 | 94 |

Liechtenstein | 1.0 | 39 | 37.3 | 36 | 0.2 | 40 | 2.3 | 22 |

Lithuania | 2.3 | 20 | 51.4 | 20 | 0.8 | 21 | 1.7 | 41 |

Luxembourg | 8.4 | 2 | 76.4 | 2 | 7.6 | 2 | 5.2 | 10 |

Macao | 0.0 | 91 | 0.0 | 95 | 0.0 | 99 | 0.0 | 95 |

Malaysia | 4.0 | 14 | 62.7 | 13 | 1.0 | 17 | 5.6 | 8 |

Malta | 4.3 | 12 | 60.5 | 16 | 1.7 | 11 | 6.6 | 6 |

Mauritius | 1.3 | 36 | 36.8 | 37 | 0.2 | 37 | 3.4 | 15 |

Mexico | 0.0 | 92 | 0.0 | 96 | 0.0 | 100 | 0.0 | 96 |

Mongolia | 0.2 | 57 | 13.6 | 59 | 0.0 | 65 | 0.1 | 60 |

Namibia | 0.0 | 93 | 0.0 | 97 | 0.0 | 78 | 0.0 | 97 |

Netherlands | 7.7 | 3 | 66.7 | 8 | 3.5 | 4 | 9.6 | 2 |

New Zealand | 0.2 | 58 | 14.0 | 58 | 0.0 | 67 | 0.1 | 64 |

Nigeria | 0.0 | 94 | 0.0 | 98 | 0.0 | 79 | 0.0 | 98 |

Norway | 2.0 | 25 | 42.7 | 30 | 0.6 | 24 | 1.9 | 38 |

Oman | 2.3 | 21 | 63.4 | 12 | 0.5 | 29 | 3.1 | 16 |

Pakistan | 0.0 | 95 | 0.0 | 99 | 0.0 | 80 | 0.0 | 99 |

Panama | 0.0 | 96 | 0.0 | 100 | 0.0 | 101 | 0.0 | 100 |

Peru | 0.0 | 97 | 0.0 | 101 | 0.0 | 75 | 0.0 | 101 |

Philippines | 0.0 | 98 | 0.0 | 102 | 0.0 | 81 | 0.0 | 102 |

Poland | 1.4 | 34 | 39.8 | 34 | 0.2 | 38 | 1.9 | 39 |

Portugal | 1.0 | 40 | 37.4 | 35 | 0.1 | 42 | 1.0 | 48 |

Puerto Rico | 0.0 | 99 | 0.0 | 103 | 0.0 | 82 | 0.0 | 103 |

Qatar | 1.3 | 37 | 22.6 | 51 | 1.1 | 16 | 3.1 | 17 |

Romania | 1.8 | 29 | 41.6 | 31 | 0.5 | 28 | 2.2 | 26 |

Russian Federation | 0.1 | 68 | 5.1 | 72 | 0.1 | 50 | 0.0 | 67 |

Saudi Arabia | 0.1 | 69 | 15.3 | 56 | 0.6 | 27 | 0.1 | 59 |

Serbia and Mont. | 0.1 | 71 | 5.2 | 71 | 0.2 | 41 | 0.0 | 73 |

Seychelles | 0.0 | 101 | 0.0 | 104 | 0.0 | 102 | 0.0 | 104 |

Singapore | 6.1 | 6 | 67.4 | 7 | 4.3 | 3 | 7.4 | 4 |

Slovak Republic | 5.3 | 8 | 68.2 | 6 | 2.1 | 8 | 4.7 | 11 |

Slovenia | 2.0 | 26 | 49.3 | 23 | 0.7 | 22 | 1.5 | 43 |

South Africa | 0.1 | 72 | 16.1 | 55 | 0.0 | 76 | 0.1 | 61 |

Spain | 3.6 | 15 | 45.7 | 27 | 2.0 | 9 | 5.4 | 9 |

Suriname | 0.0 | 100 | 0.0 | 105 | 0.0 | 103 | 0.0 | 105 |

Sweden | 4.5 | 11 | 57.6 | 18 | 1.4 | 13 | 2.3 | 24 |

Switzerland | 3.2 | 16 | 50.9 | 21 | 1.0 | 19 | 3.0 | 19 |

Taiwan Province | 0.0 | 104 | 4.9 | 73 | 0.0 | 83 | 0.0 | 77 |

Thailand | 0.0 | 102 | 3.5 | 76 | 0.0 | 104 | 0.0 | 82 |

Trinidad and Tob. | 0.1 | 70 | 7.3 | 64 | 0.0 | 63 | 0.4 | 52 |

Tunisia | 0.0 | 103 | 0.0 | 106 | 0.0 | 105 | 0.0 | 106 |

Turkey | 0.6 | 50 | 19.6 | 53 | 0.1 | 49 | 0.0 | 68 |

Ukraine | 0.3 | 54 | 20.9 | 52 | 0.2 | 36 | 1.1 | 47 |

United Arab Emirates | 2.8 | 17 | 64.2 | 10 | 1.0 | 18 | 4.1 | 13 |

UK | 13.4 | 1 | 74.4 | 4 | 13.8 | 1 | 12.8 | 1 |

USA | 0.0 | 106 | 0.1 | 80 | 0.0 | 106 | 0.0 | 81 |

Uruguay | 0.0 | 105 | 0.0 | 107 | 0.0 | 107 | 0.0 | 107 |

Venezuela | 0.0 | 107 | 3.7 | 75 | 0.0 | 73 | 0.0 | 72 |

Virgin Islands USA | 0.0 | 108 | 0.0 | 108 | 0.0 | 108 | 0.0 | 108 |

Virgin Islands UK | 0.8 | 49 | 35.8 | 45 | 0.0 | 59 | 2.1 | 36 |

Appendix C1: The adapted shortest path algorithm

This appendix describes the adaptations to the standard shortest path algorithm required to fit the optimal tax routes. Although this material is mainly theoretical, we also include the results of computations to motivate the choice we made concerning the credit method in conduit situations.

The standard all-pair shortest path problem (APSP) is solved with the Floyd–Warshall algorithm.Footnote 38 The core of this algorithm is the next comparison, where \( d_{ij}^{m} \) is the length of the shortest path from i to j allowing only the first m vertices (countries) as intermediate stations.

The algorithm is initialized with the distance matrix, which contains all the relevant information (\( D^{0} = D \)). By consecutively allowing an additional vertex as intermediate station, the length of the shortest path over the whole network is computed for all possible pairs (\( S = D^{\text{N}} \)). The efficiency of the algorithm is that with a fixed and limited number of additions and comparisons, each of the order \( {\text{N}}^{3} \), hence not polynomial, it completes the job.

The core comparison of the algorithm reflects that in the world of transportation distances simply can be added. This is obviously not the case for tax rates, as the base for taxation with a second rate, are the profits after the first tax. The first adaptation makes the switch to the multiplicative character of taxes and corresponds with deduction as the method for double taxation relief.

The tax rates include the non-resident withholding taxes, which are given for a country pair, i.e. from i to j. The country-specific corporate income taxes (CITs) are included as part of the compounded tax distances for inward income flows (see Sect. 2). This is the second adaption.

There is a convenient consequence of including the CIT of a home country in the tax distances applying to its inward flows. For countries with exemption as their double tax relief method, it amounts to having a CIT of zero. Their actual CIT only matters when these countries are the initial host on a repatriation path.

In general, for any tax route, with an initial host \( k = 1 \) and final destination \( k = {\text{n}} \), the full combined effective tax rate equals \( 1 - (1 - t_{1} )\left( {\prod\nolimits_{k = 2}^{n} {(1 - d_{k - 1,k} )} } \right) \). Here \( t_{1} \) denotes the CIT of country 1, and \( d_{1,2} = w_{1,2} \) is the bilateral withholding tax rate from 1 to 2. The other tax distances are either the bilateral withholding tax rates, \( d_{k - 1,k} = w_{k - 1,k} \), when country k applies exemption, or they include the CIT of the intermediate home country k, \( d_{k - 1,k} = 1 - (1 - w_{k - 1,k} )(1 - t_{k} ) \), when it applies deduction as double tax relief. The adapted Floyd–Warshall takes care of the product of the tax distances, in which the order is inconsequential.Footnote 39 Thus, a basic method is defined, with a deduction “metric”, covering both deduction and exemption as double tax relief methods.Footnote 40

Incorporating the credit method introduces a complexity which requires two final adaptations. The question is which taxes can be credited against the corporate tax in the final or intermediate, home country. Roughly three possibilities can be identified: (1) all taxes paid on the preceding tax route are credited, (2) only the taxes actually paid in the last preceding jurisdiction are credited, and (3) the nominal CIT rate of the last preceding jurisdiction is credited, whether this CIT is paid or not. In the latter case also the withholding tax would be credited.Footnote 41

The option of crediting the nominal CIT of the last preceding country, option iii), has the advantage that nothing needs to be known of the route before that last country visited. Moreover, it fits into the method described above, with the definition of tax distance also given in the main text:

The first option may be most in line with the philosophy of the credit method, i.e. capital export neutrality. In practice it may be difficult, or undesirable, to account for all the accumulated taxes paid on a tax route. These total taxes include the treatment of the CIT of the evaluated jurisdiction. However, it must be realized that the treatment of the CIT in the jurisdiction under consideration is based on the initial distance matrix, so that the credit is based on the nominal tax rate of the previous jurisdiction on the path instead of the actual total taxes paid. This excludes implementing the first two options.

Acknowledging that the practice of the credit method is complex and that we have no structural information on the actual operation of the method we decided on the next implementation: we let the world average CIT be credited,Footnote 42 in combination with the actual withholding tax of the last conduit jurisdiction preceding the parent jurisdiction with the credit method.

We believe this solution is the most realistic among possible alternatives. A first alternative approach would be to assume that no taxes at all were paid so that no credits are applied. This would seriously underestimate the potential reduction of the tax burden for MNEs by treaty shopping. We find a world average optimal dividend repatriation tax of 9.87% instead of 5.75%. On the other hand, taking the statutory CIT of a conduit country as the basis for tax credit would overestimate the potential reduction as this CIT is not likely to be paid in full because of double tax relief. Moreover, with this alternative, the optimal tax routes would make use of those conduit countries that apply exemption but which have a high nominal CIT, which then would be credited. The world average optimal rate found for this alternative is 3.26%, reflecting the underestimation compared to the 5.75% when the world average CIT is credited.

Furthermore, it must be observed that the world average tax rate is only applied in those conduit situations where a jurisdiction with the credit method follows a conduit country. When the last preceding jurisdiction is the starting point of a tax route, the corporate income tax is paid in the initial host and is credited in the next stop of a tax route.

This gives rise to the final adaptation of the shortest path algorithm. Let \( d_{ij} \) denote the usual tax distance between i and j when i is the first node of a path, and let \( p_{ij} \) denote the distance between i and j when i is an intermediate node on a path. This second distance incorporates the assumption dealing with the credit method.

Let \( p_{ij}^{N} \) be the output of the Floyd–Warshall algorithm with the deduction “metric” applied to distances for intermediate stations. Thus, all shortest distances are known for the inner work of tax routes, i.e. when the first vertex of the route eventually is the second. Then the outer work of initial vertices (jurisdictions) can be added as follows.

Finally, we briefly discuss two relief options that we have not covered. Instead of allowing both the corporate tax of the host country and the withholding tax to be credited, some countries only allow the withholding tax to be credited against their corporate tax. The latter method is referred to as a direct foreign tax credit whereas the former is the indirect tax credit method. For conduit situations we use the indirect credit method. The direct credit method could also easily have been implemented; it suffices to define the tax distance for i as a first vertex of a tax route; see below. We have, however, not collected information on countries applying direct rather than indirect credits.

Some countries provide no-relief-at-all for double taxation; the combined tax rate for a direct route equals:

In conduit situations problems similar to those with indirect credits occur, although no-relief-at-all is not likely to occur in conduit situations. Nevertheless, we have not covered it.

6.1 Generating all shortest paths, and all those within range

The Floyd–Warshall algorithm is an efficient method to compute the value of the strict shortest paths for all pairs of nodes of a network. With a small addition to the algorithm, the so-called penultimate vertex matrix (PVM) can be maintained. Upon completion of the Floyd–Warshall algorithm, shortest paths for all country pairs can be reconstructed from this matrix. The PVM method generates only a single strict shortest path for a given pair. We, however, require all shortest paths of a given pair, to be able to compute centrality measures. In addition, we are also interested in those paths for a given pair with a length that is within a prespecified admissible range on top of the value of the strictly shortest path. The PVM method is not suitable for generating all those relevant paths.

Instead we implement a branch and bound method. The branching consists of a full, depth-first enumeration of all possible combinations. The bounding is accomplished with the values of the strict shortest paths which were computed with the Floyd–Warshall algorithm, executed beforehand. This implementation is a brute-force approach. It is only possible because the relevant paths are not too long, with a sequence of five or six countries as a maximum. Polak (2015) describes a relative efficient implementation of the brute-force method.

Appendix C2: The betweenness centrality measure and flows

Country—weights \( w_{i} \) are defined as \( w_{i} = GDP_{i} /\sum\limits_{k} {GDP_{k} } \). Of course, \( \sum\limits_{i} {w_{i} } = 1 \).

Double GDP—weights on the flows \( (i,j) \) are:

By construction \( \sum\limits_{i} {\sum\limits_{j \ne i} {w_{ij} = 1} } \). The weights are the flows when 1 euro or dollar is run through the network; they are the shares of the total of the flows.

The measure of betweenness centrality for vertex k, \( B_{k} \), is computed from the number of times vertex k is on a relevant path from i to j, excluding k as start and end point, \( n_{kij} \), as a share in the total number of relevant paths from i to j, \( N_{ij} \), and then these fractions are weighted over all pairs i and j. \( B_{k} = \sum\limits_{i \ne k} {\sum\limits_{j \ne i,k} {w_{ij} \frac{{n_{kij} }}{{N_{ij} }}} } \)

The assumption is that each of the relevant paths between i and j takes the same share, i.e. \( 1/N_{ij} \), of the total flow of the pair ij, whose share is \( w_{ij} \). The weights can be given the interpretation of the relative size of the undiverted bilateral flows. By construction betweenness centrality then measures the share of total undiverted flows that run through a vertex, excluding all the flows that start or end at the given vertex k.

Appendix D1: Gravity variables

This appendix presents summary statistics and results for the gravity variables. GDP and distance (in kilometres) are measured in logs. The indicator for institutional quality is an average of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (World Bank 2016), each ranked between − 2.5 and 2.5. A higher value implies higher institutional quality. The geographic variables are downloaded from CEPII. Countries are only in 3% of the cases close neighbours. Of the country pairs 11% has a common language, 2% has a colonial relation, 26% a common regional trade agreement, and 27% has a common legal system (Table 15).

The coefficients for the gravity variables in the OLS regressions are found in Table 16. GDP in the host and home country has a positive impact on the bilateral FDI stock. This is also the case for institutional quality in both countries. Benassy-Quere et al. (2007) and Egger et al. (2009), among others, use GDP per capita instead of institutional quality. Both variables are heavily correlated. We have chosen for institutional quality because the explanatory power is higher in our sample. Distance has the expected negative effect on the size of the bilateral FDI stock; a common language increases bilateral investments, as is also the case for contiguity, a colonial relationship in the past, OECD membership of both countries and a common legal system. A regional trade agreement RTA and a former common country also increase FDI, but the coefficients of these variables are not significant.

The results for the gravity variables in the robustness analysis are given in Table 17.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van ‘t Riet, M., Lejour, A. Optimal tax routing: network analysis of FDI diversion. Int Tax Public Finance 25, 1321–1371 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-018-9491-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-018-9491-6