Abstract

Climate change will likely affect several of the dimensions that determine people’s food security status in Bangladesh, from crop production to the availability and accessibility of food products. Crop diversification is a form of adaptation to climate change that reduces exposure to climate-related risks and has also been shown to increase diet diversity, reduce micronutrient deficiencies, and positively affect agro-ecological systems. Despite these benefits, the level of crop diversification in Bangladesh remains extremely low, requiring an examination of the factors that support uptake of this practice. This paper explores whether women’s empowerment, measured using the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI), leads to increased diversification in the use of farmland. Our results reveal that some aspects of women’s empowerment in agriculture, but not all, lead to more diversification and to a transition from cereal production to other crops like vegetables and fruits. These findings suggest a possible pathway for gender-sensitive interventions that promote crop diversity as a risk management tool and as a way to improve the availability of nutritious crops.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Despite recent reductions in poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition remain serious problems in Bangladesh. As of 2014, a quarter of the population, 40 million people, were food insecure and 11 million of them suffered from acute hunger (Osmani et al. 2016). Remarkably high levels of stunting are observed in children under the age of five, with 36% suffering from chronic malnutrition and 14% from acute malnutrition (USAID 2018).

It is in this challenging context that climate change will take place with potentially significant adverse effects for the agriculture sector. The existing literature indicates that climate change will affect people’s food security and livelihoods by deteriorating the general conditions in which farmers operate and by reducing the availability of food products. In particular, climate change is expected to adversely reduce rice production in each of the country’s three growing seasons and have significant negative impacts on fisheries due to the increased intensity and frequency of extreme events, such as coastal cyclones and flooding (Ruane et al. 2013; Ara et al. 2016). In addition to the direct effects on crop productivity, climate change will also affect the nutritional value of food products (Fanzo et al. 2017). Consequently, Bangladesh’s geographical exposure and intensive rice monoculture make it one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change.

A rich body of literature explores the strategies that farmers can use to cope with climate change (FAO 2017; Owen 2020) and climate adaptation is already underway in Bangladesh, particularly in the drought-prone areas where farmers have recently begun to change cropping systems and calendars, crop varieties, and agronomic practices, and started adopting improved animal husbandry (Kabir et al. 2017). We focus on crop diversification as a form of adaptation. Crop diversification refers to those ecologically diversified production systems that depart from monocropping and single cereal-based farming systems. The leading advantage of crop diversification is the redundancy that different species build into the production system (Vandermeer et al. 1998; Lin 2011). The different sensitivity of multiple species to environmental fluctuations means that effects of the failure or underperformance of one crop can be mitigated by the performance of another. In combination with agricultural practices, such as rotations, intercropping, and agroforestry, crop diversification has the potential to increase productivity, improve farmers’ livelihoods, increase biodiversity, and support the provision of ecosystem services (Asfaw et al. 2019; Tittonell et al. 2016; McCord et al. 2015). In several contexts, diversified cropping systems have indeed been found to be more robust, better suited to cope with future climate risks (Werners et al. 2007; Smit and Skinner 2002), and capable of stabilizing and increasing income from production under climatic shocks (Makate et al. 2016).

There are other possible benefits generated by crop diversification that contribute to the broader capacity of a household to adapt to climate change, particularly in the presence of poorly functioning markets. Among these benefits are increasing opportunities to engage with local markets because of the greater variety of farm products (McCord et al. 2015; Keleman et al. 2013), a potential for greater dietary diversity (Fraval et al. 2019; Bellon et al. 2016), and reduced micronutrient deficiencies and malnutrition (Carletto et al. 2015; Islam et al. 2018). Despite all these benefits, crop diversification must be evaluated carefully in the context in which it takes place. The efficient production and sale of staple or cash crops can improve households’ incomes with the ultimate effect of increasing adaptation capacity and diversifying and stabilizing consumption (Darrouzet-Nardi and Masters 2015; Passarelli et al. 2018). In some contexts, diversification can lead to inefficiencies and losses in dietary diversity due to foregone income (Sibhatu et al. 2015). Yet, in a recent study on rural livelihoods across sub-Saharan Africa, Fraval et al. (2019) recommend that interventions designed to improve food access through income generation should also promote crop and livestock production diversity.

An important and growing area of inquiry is related to women's participaton in climate change adaptation efforts and particularly to the role of women's empowerment. Knowledge about the effects of climate change on women (Jost et al. 2016; Chanana-Nag and Aggarwal 2020) and their vulnerable status (Perez et al. 2015; Huyer et al. 2015) is mounting. However, while it is now established that gender-related barriers can limit households’ capacity to adapt to climate change (McKinley et al. 2018; Huyer and Partey 2020), more attention must be given to women’s active role in adaptation. Women’s empowerment is documented to influence agricultural technical efficiency and spending choices, the sourcing and preparing of foods, diet quality and dietary diversity, and households’ nutrition outcomes (Seymour 2017; Ruel et al. 2018; Seymour et al. 2019). The use of the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI)—an index-based approach to measuring women’s agency and involvement in agriculture—has enabled a deeper examination of the linkages between empowerment and development outcomes (Alkire et al. 2013).

This paper explores the relationship between women’s empowerment and crop diversification. While diversification plans in Bangladesh already include expanding areas allocated to wheat and maize at the expense of rice, we are particularly interested in non-cereals given their contribution to climate change adaptation for reasons that go beyond direct effect on incomes. Growing vegetables and fruits would add physiological diversity in the field providing additional protection against climate change risks and would have positive implications for diets and nutrition. In many countries it is common to find that men and women traditionally control different crops. The conventional wisdom is that men, being responsible for the family income, grow cash and export crops, while women, who are responsible for feeding the family, prefer to grow crops that satisfy the household’s needs (Safilios-Rothschild 1990; Carr 2008). It is generally difficult to discern whether women grow different crops due to insufficient access to land, resources, and information; or because of time constraints; or due to differences in preferences compared to men (Doss 2002). We do not resolve this dispute, but by investigating the connection between women’s empowerment and crop diversification, we open additional areas of inquiry about the role of women in climate change adaptation and reveal intervention pathways relevant to reaching greater levels of adaptation.

2 Background and context

Records show that in Bangladesh from 1948 to 2011, yearly mean temperatures have risen by 0.64 °C. Temperatures in the pre-monsoon and monsoon seasons rose by 6 and 11%, respectively (Ahasan et al. 2010; Bari et al. 2016), and projections based on several global circulation models indicate this trend is expected to continue. Mean temperatures are projected to increase about 1.4 °C by 2050 and 2.4 °C by 2100 from the 1960 baseline (USAID 2012). A survey of four different climate models (De Pinto et al. 2017) reveals that by 2050, changes in the mean daily maximum temperature of the warmest month—one of the standard indicators of potential heat stress for agriculture—are projected to range from 1.9 to 4.7 °C nationally and changes in mean annual rainfall from 164 to 352 mm.

Changes in growing conditions are expected to have significant effects on crop production. Simulations obtained using a crop model (DSSAT, Jones et al. 2003) and four different climate models show that the effects on yields of all major crops are generally negative, although the magnitude of the effects varies across crops (De Pinto et al. 2017). In addition, by being located in a predominantly low-lying region at the intersections of the Ganga, Meghna, and Brahmaputra rivers, Bangladesh is one of the most vulnerable countries to flooding due to a combination of storm surge, sea level rise, and higher precipitation (Karim and Mimura 2008). Flooding is not the only threat to agricultural production; salinization from intruding sea water in coastal areas also limits crop yields and reduces agricultural land availability (Rabbani et al. 2013). The combination of reduced yields and flooding is also expected to have an overall negative impact on land value (Hossain et al. 2020).

In contexts, such as Bangladesh, where rice monocropping is predominant, crop diversification has the potential to help with adaptation on multiple fronts, including improving diets and people’s nutritional status (Headey and Hoddinott 2015). Crop diversification is an important component of agricultural policies in Bangladesh and is recognized as a mechanism for improving food and nutrition security, relieving pressure on the environment and promoting economic growth and rural development (Rahman 2009; Akanda 2010; Islam and Ullah 2012; Islam et al. 2018). Despite the policy support from the government, the level of crop diversification in the country increased only slightly between 1970 and 2010 (Islam and Rahman 2012; Islam and Hossein 2015). A few studies have identified the reasons for such low uptake. High input cost, high volatility in market opportunities, susceptibility to pests, and irrigation systems geared to rice production are all barriers to greater diversification (Metzel and Ateng 1993; Mahmud et al. 1994). Rahman (2004) also found that current levels of education, experience, and farm asset ownership affect the propensity of farmers to diversify.

A robust literature exists on the factors influencing household-level responses to climate change. Increasingly, this literature delves into how gender relations shape household-level responses (Jost et al. 2016; Twyman et al. 2014). Bryan et al. (2017) highlight four types of gender differences that are likely to affect how households adapt to climate change: preferences for technology and investment options; household roles and responsibilities; access to resources (including information, assets, financial capital, natural resources, and labor); and institutions (including group membership, market access, and social norms). Studies of the gender dimensions of climate change adaptation in Bangladesh find that women face greater vulnerabilities due to climate change and have more limited adaptive capacity (Ahmad 2012). Despite these challenges, women do participate in climate change adaptation in distinct ways when they have access to information and social networks, typically through NGO programs (Khalil et al. 2019). Women’s preferences for climate-smart practices tend to relate to their gendered roles in agriculture, such as homestead garden production, livestock care, grain and food preservation and storage, and planting roadside trees (Chaudhury et al. 2012; Corcoran-Nantes and Roy 2018).

Gender relations in Bangladesh are highly patriarchal, and women often lack access to resources and remain dependent on men for their basic needs (Kabeer 2011). Norms in the country largely limit women’s economic and agricultural activities to those tasks that can be carried out around the homestead, most often subsistence farming or post-harvest processing, for which they receive no remuneration (Heintz et al. 2018). Despite the existence of laws granting women the right to own and inherit land, the transmission of property through the male line often persists in practice, resulting in women being largely excluded from landownership (Kieran et al. 2015). Women’s access to and control over income, assets, credit, agricultural inputs, and extension services are also severely limited (Quisumbing et al. 2013). Nonetheless, in recent years, new pathways for women’s empowerment have emerged thanks to increases in opportunities outside the home in new industries, such as garment factories (Heath and Mobarak 2015; Mottaleb and Sonobe 2011), greater engagement in agricultural wage labor (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) 2018), and the expansion of women’s social networks through community groups (Kabeer 2017). These recent advancements highlight the importance of exploring the role of women’s empowerment in the context of climate change.

3 Methods

Economists have borrowed metrics from biology and ecology to quantify crop diversification. Among the most common are those based on Shannon’s entropy measure and on the Simpson index (also known as the Herfindahl index). Indexes based on Shannon’s entropy (\( H=-\sum \limits_{i=1}^J{s}_i\ln {s}_i \), where s is the share of farmland allocated to a particular crop or crop category and i indicates one of the 1…. J possible crops or crop categories grown by farmers) can be used to measure the diversity and evenness of observed land allocations. Other indexes emphasize other aspects of diversity. For example, the Simpson index (\( SI=\sum \limits_{i=1}^J{s}_i^2 \)) compares the proportional abundance of a series of crops but puts a greater emphasis on dominant crops (see Magurran 2004 for a review of measures of diversity).

These indexes can be used to explore the relationship between women’s empowerment and crop diversification using many different econometric techniques, including simple ordinary least square (OLS). However, there are limits to the insights gained by investigating crop diversification using such methods since the index hides the possible transitions across crops that lead to an increase or decrease in diversification. Alternative approaches can provide greater insights into the changes in land allocations that lead to changes in crop diversification. With this in mind we build a behavioral economic model of farmland allocations, the underlying parameters of which can be estimated using a discrete choice model. Discrete choice models are econometric models particularly suited to handle decision-making process that produce discrete or categorical outcomes and have been used before in analyses of farmland allocations (Wu and Segerson 1995; Carpentier and Letort 2014; De Pinto et al. 2019).

We consider an agricultural production system in which each one of the n households can allocate their land of size A to a series of J competing different crops. Producers are risk-neutral price takers who make land allocation decisions that maximize the utility of farming their landFootnote 1:

where aj is the area allocated to crop j, Πj is the plot-level gross profit for that crop, and C identifies the household-specific acreage management costs, which act as binding constraints on acreage choices and capture the effects of limiting quantities of quasi-fixed inputs (Carpentier and Letort 2014). The acreage management costs are dependent on a combination of factors that can affect the monetary and non-monetary costs of managing alternative crop allocations. These factors include quasi-fixed inputs, such as agricultural machinery, that can limit the land that can be devoted to a given crop, incompatible planting and harvesting dates of alternative crops, and women’s time constraints, which create potentially large differentials in the opportunity cost of alternative crop allocations.

Thus, there is an optimal area allocation \( {a}_j^{\ast }=F\left[\Pi, C,A\right] \) to each use that solves the farmer’s utility maximization problem.Footnote 2 We assume that \( \kern0.5em {a}_j^{\ast }=F\left[\Pi, C,A\right] \) can be expressed as \( {a}_j^{\ast }=A\ast f\left[\Pi, C,A\right]. \)Footnote 3 Accordingly, for each use j there is an optimal share allocation function:

Note that since \( \sum \limits_{j=1}^J{a}_j=A \), it follows that \( \sum \limits_{j=1}^J{s}_j= \)1. The outcome of the utility maximization process, i.e., farmland allocations, is observable either through remote sensing or recorded in household surveys, and it allows us to set up the problem in terms of choice probabilities as follows. The probability that a farmer chooses to grow a particular crop j is given by Pj = Pr (Uj > Ui ∀ j ≠ i) which can be rewritten in terms of the share s of farmland allocated to use j: \( {s}_j=\frac{1}{A}\left[A\ast \mathit{\Pr}\left({U}_j>{U}_i\forall j\ne i\right)\right] \). Acknowledging that U = V + ξ where V represents a knowable-by-all component of the utility function while ξ is known to the farmer but unobserved by the researcher and assuming that ξ has an iid Type 1 EV distribution, then the probability of observing sj is given by a multinomial logit (MNL) formula:

and, given our modeling settings, the optimal share allocation function can be written as:

For our modeling purposes, we group the j crops into broad crop categories, cereals, vegetables, and fruits, while cash crops are lumped into an additional category that includes all other uses (Table 1). These broad categories are based on the role that crops play in Bangladeshi agriculture and their different physiological and nutritional characteristics. Our increasing understanding of the importance of fruit consumption in healthy diets (Springmann et al. 2016), particularly in the presence of climate change, motivates our decision to dedicate a category to fruit crops. The grouping of the cash crops together with other uses is for modeling reasons. Our model estimation relies on identifying a stream of monetary benefits for all land allocations, but our dataset only provides information about the gains accruing from crop production. By joining cash crops with other uses, we assume that the benefits generated by these crops are a sufficient proxy for those generated by all other land utilizations. We experimented with alternative land categorizations. For example, in one specification, we swapped the role of fruit crops and other crops. Fruit crops were included in the “other uses” category, while cash crops were modeled with a dedicated category, as in the case of cereals and vegetables. This change did not significantly alter qualitatively the estimated parameters.

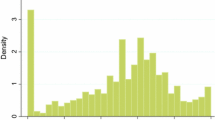

The empirical analysis begins by looking at the direct relationship between women’s empowerment and crop diversification using an OLS regression (model 1). In this regression, the dependent variable is a crop diversification index based on Shannon’s entropy that considers that share s of each crop category normalized by the natural logarithm of the total number J of categories considered (\( H=-\frac{\sum \limits_{i=1}^J{s}_i\ln {s}_i}{\ln J} \)) so that the value of the function is bounded below by zero and above by unity. We explored the use of other indexes like the Simpson index, but there are no substantial differences in the results obtained using these alternatives.

To understand with more specificity how women’s empowerment might affect land allocations and potentially draw land away from the highly predominant cereal production, we use the fractional MNL model implied by Eq. 4. To estimate this model, we assumed that the optimal share function for each crop can be approximated by a linear-in-parameter combination of explanatory variables (see the appendix for an example of this linearization) such that \( \ln \left(\frac{s_{jn}}{s_{0n}}\right)={\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\boldsymbol{j}}{\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{j}\boldsymbol{n}}+{\boldsymbol{\xi}}_{\boldsymbol{j}} \), where Xjn is a vector of explanatory variables, βj is a vector of parameter to be estimated, ξj is an error term, and the subscript 0 in s0 indicates a reference crop category.

The parameters βj are estimated using a pseudo-maximum likelihood method as proposed by Mullahy (2015). Given the optimal share allocation function \( {s}_j^{\ast } \) (Eq.Undefined control sequence \varPi4), and the observed land allocations \( \left({s}_{jn}^O\right) \), the quasi-log-likelihood function to be maximized with respect to the parameters βj is:

We refer readers to Mullahy (2015) for the calculation of the score equation and the parameters’ asymptotic variance.

4 Data

The data used for our analysis comes from the Bangladesh Integrated Household Survey (BIHS), collected in 2015 under the supervision of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI 2016). Covering the 2015 crop year, the survey provides information on land allocations among crops and crop-specific revenues, but only limited information about costs of production. It covers 6500 households and is statistically representative of rural Bangladesh. The BIHS provides information on crop-specific land allocations and revenues for each of the three growing seasons: Kharif 1 (mid-March to mid-July), Kharif 2 (mid-July to mid-November), and Rabi (mid-November to mid-March). A significant number of farmers do not report any planted area in the survey, and another key information for the regression is at time missing (e.g., information on women empowerment or on crop area, prices and production costs). Excluding households that do not own or operate farmland and those with the missing information, the sample size used for the empirical analysis is 3010 households.

4.1 Land allocation

Recorded land allocations are based on the primary crop grown on the plot. Table 1 shows land allocation proportions by large crop categories, as well as allocations to land used for non-agricultural purposes. Given that it is common practice in Bangladesh for crops to be grown year-round, we aggregate across the three growing seasons. Thus, the denominator for the land allocations in Table 1 is the total land owned or operated by a farmer during the 2015 agricultural year. The survey indicates that sampled farmers on average allocate 66% of their land to cereals. Vegetables occupy 9% of land, other crops (mostly cash crops, such as jute or sugarcane) account for 8%, and fruits less than 1%. However, when present on the farm, cash crops and fruit crops occupy a similar percentage of farmland, about 30%.

According to the survey (Table 2), about 17% of total land area is not in some agricultural use. This is likely an overestimation because the BIHS’ agriculture production module excludes questions on homestead gardening and does not collect information about the crops grown on pieces of land rented or leased out to other farmers. Non-agricultural land can largely be attributed to land currently kept fallow and non-arable, derelict, or commercial/residential land.

4.2 Prices, productivity shifters, and management costs

The 2015 BIHS reports crop-specific farm-gate prices, the cost of hired labor, and the unit cost of fertilizers. We control for household-specific factors that can affect productivity by using the reported value of off-farm revenues and the highest level of education achieved in a household. To control for the implicit acreage management cost, we include the number of household members which can affect the availability of labor, the value of farming tools and machinery present on the farm (value of agricultural assets), and the total size of the household landholdings. In addition, to control for gender-specific effects, we include metrics derived from the WEAI.

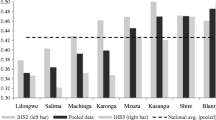

4.3 Women’s empowerment in agriculture index

The WEAI is a survey-based index collected from the primary male and female decision-makers within the same households to measure respondents’ empowerment across five domains (production decision-making, control over resources, control over income, leadership, and time allocation) within the agriculture sector (Alkire et al. 2013). We use four variables derived from the WEAI. The first is the empowerment score, which is an aggregate measure of empowerment based on ten weighted indicators across the five domains (see Table 3 for detailed descriptions and weights). Each indicator takes a value of one if a woman achieves adequacy according to cut-offs defined by Alkire et al. (2013) or zero otherwise.

Since previous studies have found that different aspects of women’s empowerment can have opposite effects on nutrition and education outcomes (Malapit et al. 2019), we examine the influence of three variables derived from sub-components of the WEAI (ownership of assets, group membership, and input in productive decisions). The first represents the number of productive assets for which the woman reports having sole or joint ownership. The second shows whether the respondent participates in at least one economic or social group in their community. The third is the proportion of agricultural activities for which the woman reports having input into most or all of the decisions. Greater asset ownership and participation in groups were chosen because previous studies have suggested that these indicators represent the largest gaps in women’s empowerment in the context of Bangladesh (Sraboni et al. 2014). We included the indicator for women’s involvement in agricultural decision-making given that this may directly influence household decisions about farm diversity.

Table 4 provides an overview of the explanatory variables used in the models and their descriptive statistics.

5 Results

The OLS regression only partially sheds light on the determinants of crop diversification. The parameter estimates of Model 1 (Table 5) for the effect of crop prices on diversification generally meet our expectations. An increase in the price of vegetables and of other uses leads to greater diversification while an increase in the price of cereals has the opposite effects. However, only the price of vegetables is statistically significant. Surprisingly, an increase in the price of fruits appears to lower diversification but the parameter is statistically insignificant. Two more variables appear to lead to greater diversification: farm size and value of farm assets. The effect of increasing the farm size is somewhat expected, and the parameter estimate is statistically significant. All the remaining variables seem to reduce crop diversification. Most importantly, the parameter for the composite women’s empowerment score is negative and indicates that an increase in women empowerment does not lead to greater crop diversification. However, this estimate is not statistically significant.Footnote 4

We now turn to the results of the fractional MNL model, estimated using two specifications: one that uses the composite women’s empowerment score (model 2) and one that uses 3 selected sub-indicators (model 3).Footnote 5 Table 6 reports the average marginal effects (AMEs), i.e., how a unit change in one variable (ceteris paribus) changes allocation choices, because they are simpler to interpret than the parameter estimates. AMEs are calculated as the average of the marginal effect calculated for each observation.

Across the two specifications, the signs of the AMEs are consistent, and the estimates for the crop price, for which we have strong prior hypotheses, meet our expectations. An own-price increase leads to an increase in the land allocated to cereals, vegetables, and fruits. There are qualitative differences in the effects that some estimated parameters have on diversification between OLS and multinomial logit models. Most of the variables, however, including education level, household size, the value of farm assets, off-farm revenues, and the prices of urea and labor, confirm the findings of the OLS estimation.

Interestingly, the AME that links women’s empowerment to crop diversification in model 2 appears to support the OLS finding. Model 2 shows that an increase in the women’s empowerment score is associated with an increase in land allocated to fruits but also to cereals. Given that most of the farmland is already allocated to cereals, the result is an even higher concentration of land in cereal production and a decreased crop diversity. Only the AME for fruits is statistically significant, but taken together, models 1 and 2 suggest that, in the aggregate, women’s empowerment does not lead to greater crop diversification.

Model 3 reveals a more complex picture and shows that different components of women’s empowerment have opposite effects on land allocation decisions. Two aspects of women’s empowerment appear to drive greater crop diversification: women’s participation in agricultural decisions and women’s participation in community groups. As women’s role in decision-making increases, less land is allocated to cereals and more land is allocated to vegetables and fruits (parameter estimates are statistically significant for cereals and fruits). A similar, statistically significant, result is found for women’s group membership. Women’s participation in economic or social groups appears to favor a greater allocation of land to vegetables and fruits and less to cereals. On the other hand, the AMEs for the assets-controlled-by-women variable suggest that as women’s share of household assets increases, more land is allocated to cereals and fruits and less land is allocated to vegetables. As explained earlier, given the existing predominance of cereals, this is equivalent to a reduction in crop diversification.

Several further insights are provided by the MNL specifications. These can be particularly useful for those aspects of adaptation related to the health of households that rely on the consumption of on-farm products for their vitamin and micronutrient intake or on the availability in local markets of foods rich in nutrients. An increase in labor costs appears to discourage the allocation of land to both vegetables and fruits, leading to an even greater concentration on cereals. A similar effect is estimated for increasing off-farm revenues and household size. An increase in the value of farm assets has the opposite effect, leading farmers to shift land away from cereals in favor of vegetables and fruits. Higher levels of education appear to favor an increase in allocation of land to vegetables and fruits even though the overall effects on crop diversification is to decrease it.Footnote 6

6 Discussion and conclusion

The results suggest a complex association between women’s empowerment and crop diversification. Although the relationship is not straightforward, it confirms that women play a role in climate change adaptation and that this role can be positive. While the use of a composite index of women’s empowerment suggests that increasing empowerment does not lead to greater levels of crop diversification, additional analysis reveals a deeper and more complex relationship between specific components of empowerment and farmland allocation decisions. Increases in women’s participation in production decisions have a positive effect on crop diversification. This reveals that women may choose a more diversified portfolio of crops when they have enough bargaining power. A similar effect can be attributed to expanding women’s social relationships outside the home via group membership, which increases women’s access to information and their bargaining power within the household. These results confirm what other studies have found, that genders have different priorities for the use of farmland (De Pinto et al. 2019) and that gender influences the management of landscapes (Villamor et al. 2015).

On the other hand, women’s control over assets seems to lead to less diversification. While this finding deserves additional exploration, we can offer an explanation based on existing evidence that suggests that in Bangladesh the poorest women are more willing to defy local norms and accept work outside the home, such as agricultural wage work (Heintz et al. 2018). Therefore, women with fewer assets may be more engaged in agricultural production activities and influence land allocation towards crops for which they provide more labor, such as vegetables, pulses, and cash crops (Rahman 2000), or those they produce for household consumption purposes. Conversely, women with greater wealth may choose to limit their involvement in agriculture given the stigma associated with working in agriculture (Kabir et al. 2019), thereby increasing men’s say in production decisions.

The complex relationship between crop diversification and women’s empowerment illustrated by our results is consistent with other research in Bangladesh that shows how different aspects of empowerment affect outcomes in different ways (Malapit et al. 2018). Although more research into these processes and additional methods of analysis should be deployed to better understand what women’s empowerment means for rural women in Bangladesh, our findings are consistent with the broader research on gender and climate change adaptation. This research suggests that although constrained by social norms, women are important determinants and contributors to households’ resilience to climate change and they can play a key role in decision-making in agriculture (Ahmad 2012; Fisher and Carr 2015; Khalil et al. 2019).

Our findings are therefore relevant for the design of gender-sensitive interventions that promote crop diversification as a form of climate change adaptation and as a way to improve households’ adaptation capacity. More broadly, the analysis makes clear how a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying women’s choices and gender relationships is essential to make gender-sensitive interventions more impactful. Gender-informed climate adaptation interventions could build upon and reinforce a history of successful work by NGOs aimed at removing the constraints that limit women’s involvement in agriculture and at promoting the adoption of rewarding agricultural technologies, such as improved varieties for homestead gardening and polyculture fish (Birner et al. 2010; Hallman et al. 2007).

Finally, work on gender issues is increasingly becoming common among practitioners and researchers alike, and the use of the WEAI in applied research is growing. Our study provides further evidence that the WEAI offers important and nuanced insights into the links between aspects of women’s empowerment and well-being outcomes. Moreover, we show that the decomposability of the WEAI is a key feature that must be utilized whenever possible. While different levels of analysis, aggregated and disaggregated, may produce similar results (Sraboni et al. 2014), ours and previous analyses show that is not always the case (Sraboni and Quisumbing 2018). Disregarding the multi-dimensional nature of women’s empowerment can lead to spurious conclusions, and the differences in the magnitude and effects associated with various domains of empowerment should not be overlooked because they provide important nuance for contextualizing overall results.

Notes

We assume that profits are a sufficient proxy for all the benefits that households derive from farming their land.

We drop the household subscript for readability.

Wu and Segerson (1995) assume that the land use function \( {a}_j^{\ast }=F\left[\Pi, A\right] \) is linear homogenous of degree one in area. However, this assumption is not necessary to obtain \( {a}_j^{\ast }=A\ast F\left[\Pi, A\right] \), and by retaining total farm size among the arguments of the optimal share function, one can in principle account for differences risk-spreading decisions available to farmers that manage farms of different sizes and the potential effect of economies or diseconomies of scale.

A similarly non-statistically significant result is found when the model is estimated using the three components of women’s empowerment.

We used a Hausman test to evaluate if our specification suffered from the IIA assumption. The results of the test indicate that the IIA assumption is not violated

Even though the statistically significant parameter for vegetables suggest that land allocated to their production should increase, so does land allocated to cereal inducing an even higher concentration of land on cereals. One can use the estimates marginal effects to evaluate the changes in the two diversity indexes considered. For example, considering the estimates for the education level in model 2 (Table 6: 0.0007; 0.0004; 0.0002) and sample mean of all land allocations (Table 1: 0.66, 0.09, 0.005, 0.245), the Shannon’s diversity index decreases from 0.496 to 0.495.

See Beattie, Bruce R. and C. Robert Taylor. The Economics of Production. Malabar: Krieger Publishing Company, 1993, page 248

References

Ahasan MN, Chowdhary Md AM, Quadir (2010) Variability and trends of summer monsoon rainfall over Bangladesh. J Hydrol Meteorol 7(1):1–17

Ahmad N (2012) Gender and climate change in Bangladesh the role of institutions in reducing gender gaps in adaptation program. Social development papers; no. 126. Social inclusion Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/559391468340182699/Gender-and-climate-change-in-Bangladesh-the-role-of-institutions-in-reducing-gender-gaps-in-adaptation-program. Accessed: July 10 2020

Akanda AI (2010) Rethinking crop diversification under changing climate, hydrology and food habit in Bangladesh. J Agric Environ Int Dev 104(1–2):3–23

Alkire S, Meinzen-Dick R, Peterman A, Quisumbing A, Seymour G, Vaz A (2013) The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Dev 52:71–91

Ara I, Lewis M, Ostendorf B (2016) Spatio-temporal analysis of the impact of climate, cropping intensity and means of irrigation: an assessment on rice yield determinants in Bangladesh. Agric Food Secur 5:12

Asfaw S, Scognamillo A, Di Caprera G, Sitko N, Ignaciuk A (2019) Heterogenous impact of livelihood diversification on household welfare: cross-country evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev 117:278–295

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). 2018. 2017 Statistical Year Book Bangladesh. Available at: http://bbs.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bbs.portal.gov.bd/page/9ead9eb1_91ac_4998_a1a3_a5caf4ddc4c6/CPI_January18.pdf. Accessed: June 10 2019

Bari SH, Rahman MTU, Hoque MA, Hussain MM (2016) Analysis of seasonal and annual rainfall trends in the northern region of Bangladesh. Atmos Res 176–177:148–158

Bellon MR, Ntandou-Bouzitou GD, Caracciolo F (2016) On-farm diversity and market participation are positively associated with dietary diversity of rural mothers in Southern Benin, West Africa. PLoS One 11(9):e0162535

Birner R, Quisumbing AR, Ahmed N (2010) Cross-cutting issues: governance and gender. Washington, DC, USA: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1048.6083&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Bryan E, Theis S, Choufani J, De Pinto A, Meinzen-dick R, Ringler C (2017) Agriculture for improved nutrition in Africa south of the Sahara. In: De Pinto A (ed) 2017 Annual trends and outlook report (ATOR). A thriving agricultural sector in a changing climate: the contribution of climate-smart agriculture to Malabo and sustainable development goals. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D.C., pp 114–135

Carletto G, Ruel M, Winters P, Zezza A (2015) Farm-level pathways to improved nutritional status: introduction to the special issue. J Dev Stud 51:945–957

Carpentier A, Letort E (2014) Multicrop production models with multinomial logit acreage shares. Environ Resour Econ 59:537–559

Carr ER (2008) Men’s crops and women’s crops: the importance of gender to the understanding of agricultural and development outcomes in Ghana’s central region. World Dev 36(5):900–915

Chanana-Nag N, Aggarwal PK (2020) Woman in agriculture, and climate risks: hotspots for development. Clim Chang 158:13–27

Chaudhury M, Kristjanson P, Kyagazze F, Naab JB, Neelormi S (2012) Participatory gender-sensitive approaches for addressing key climate change-related research issues: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ghana, and Uganda. Working Paper 19. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Available at https://ccafs.cgiar.org/sites/default/files/assets/docs/ccafs-wp-19-participatory_gender_approaches.pdf. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Corcoran-Nantes Y, Roy S (2018) Gender, climate change, and sustainable development in Bangladesh. Balancing individualism and collectivism. Springer, Cham, pp 163–179

Darrouzet-Nardi AF, Masters WA (2015) Urbanization, market development and malnutrition in farm households: evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys, 1986–2011. Food Sec 7:521–533

De Pinto A, Meinzen-Dick R, Choufani J, Theis S, Bhandary P (2017) Climate change, gender, and nutrition linkages. Research Priorities for Bangladesh. IFPRI, GCAN Policy Note 4. Available at: http://gcan.ifpri.info/files/2017/08/Research-Priorities-for-Bangladesh-Policy-Note.pdf. Accessed: June 10, 2019

De Pinto A, Smith VH, Robertson RD (2019) The role of risk in the context of climate change, land use choices and crop production: evidence from Zambia. Clim Res 79(1):39–53

Doss CR (2002) Men’s crops? Women’s crops? The gender patterns of cropping in Ghana. World Dev 30(11):1987–2000

Fanzo J, McLaren R, Davis C, Choufani J (2017) Climate change and variability. What are the risks for nutrition, diets, and food systems? IFPRI Discussion Paper 1645. Accessed June 10 2019

FAO. Climate Smart Agriculture Sourcebook [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jun 20]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture-sourcebook/en/. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Fisher M, Carr ER (2015) The influence of gendered roles and responsibilities on the adoption of technologies that mitigate drought risk: the case of drought-tolerant maize seed in eastern Uganda. Glob Environ Chang 35:82–92

Fraval S, Hammond J, Bogard JR, Ng'endo M, van Etten J, Herrero M, Oosting SJ, de Boer IJM, Lannerstad M, Teufel N, Lamanna C, Rosenstock TS, Pagella T, Vanlauwe B, Dontsop-Nguezet PM, Baines D, Carpena P, Njingulula P, Okafor C, Wichern J, Ayantunde A, Bosire C, Chesterman S, Kihoro E, Rao EJO, Skirrow T, Steinke J, Stirling CM, Yameogo V, van Wijk MT (2019) Food access deficiencies in sub-Saharan Africa: prevalence and implications for agricultural interventions. Front Sustain Food Syst 3:104

Hallman K, Lewis D, Begum S (2007) Assessing the impact of vegetable and fi shpond technologies on poverty in rural Bangladesh. In: Adato M, Meinzen-Dick R (eds) Agricultural research, livelihoods, and poverty: studies of economic and social impacts in six countries. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Headey DD, Hoddinott JF (2015) “Agriculture, Nutrition, and the Green Revolution in Bangladesh.” IFPRI Discussion Paper 01423. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D.C.

Heath R, Mobarak AM (2015) Manufacturing growth and the lives of Bangladeshi women. J Dev Econ 115:1–15

Heintz J, Kabeer N, Mahmud S (2018) Cultural norms, economic incentives and women’s labour market behaviour: empirical insights from Bangladesh. Oxf Dev Stud 46(2):266–289

Hossain MS, Arshad M, Qian L, Kächele H, Khan I, Islam MDI, Mahboob MG (2020) Climate change impacts on farmland value in Bangladesh. Ecol Indic 112:106181

Huyer S, Partey S (2020) Weathering the storm or storming the norms? Moving gender equality forward in climate-resilient agriculture. Clim Chang 158:1–12

Huyer S, Twyman J, Koningstein M, Ashby J, Vermeulen SJ (2015) Supporting women farmers in a changing climate: five policy lessons. Copenhagen, Denmark. Available at https://cgspace.cgiar.org/rest/bitstreams/60479/retrieve. Accessed 6 August 2020

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) (2016) Bangladesh Integrated Household Survey (BIHS) 2015. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC

Islam MM, Hossein E (2015) Crop diversification in Bangladesh: constraints and potentials. Bangladesh economic association conference paper. Available at: https://bea-bd.org/site/images/pdf/057.pdf. Accessed: December 12, 2019

Islam N, Rahman MM (2012) An assessment of crop diversification in Bangladesh: a spatial analysis. Appl Econ Lett 19:29–33

Islam S, Ullah MR (2012) The impacts of crop diversity in the production and economic development in Bangladesh. Int J Econ Finance 4(6):169–180

Islam AHMS, von Braun J, Thorne-Lyman AL, Ahmed AU (2018) Farm diversification and food and nutrition security in Bangladesh: empirical evidence from nationally representative household panel data. Food Security 10:701–720

Jones JW, Hoogenboom G, Porter CH, Boote KJ, Batchelor WD, Hunt LA, Wilkens PW, Singh U, Gijsman AJ, Ritchie JT (2003) DSSAT cropping system model. Eur J Agron 8:235–265

Jost C, Kyazze F, Naab J, Neelormi S, Kinyangi J, Zougmore R et al (2016) Understanding gender dimensions of agriculture and climate change in smallholder farming communities. Clim Dev 8(2):1–12

Kabeer N (2011) Between affiliation and autonomy: navigating pathways of women’s empowerment and gender justice in rural Bangladesh. Dev Chang 42(2):499–528

Kabeer N (2017) Economic pathways to women’s empowerment and active citizenship: what does the evidence from Bangladesh tell us? J Dev Stud 53(5):649–663

Kabir J, Alauddin M, Crimp S (2017) Farm-level adaptation to climate change in Western Bangladesh: an analysis of adaptation dynamics, profitability and risks. Land Use Policy 64:212–224

Kabir MS, Markovi’c M, Radulovi’c, D. (2019) The determinants of income of rural women in Bangladesh. Sustainability 11:5842

Karim MF, Mimura N (2008) Impacts of climate change and sea-level rise on cyclonic storm surge floods in Bangladesh. Glob Environ Chang 18(3):490–500

Keleman A, Hellin J, Flores D (2013) Diverse varieties and diverse markets: scale-related maize ‘profitability crossover’ in the Central Mexican highlands. Hum Ecol 41(5):683–705

Khalil MB, Jacobs BC, McKenna K, Kuruppu N (2019) Female contribution to grassroots innovation for climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Climate and Development 12(7):664–676

Kieran C, Sproule K, Doss CR, Quisumbing AR, Kim SM (2015) Examining gender inequalities in land rights indicators in Asia. Agric Econ 46:1–20

Lin BB (2011) Resilience in agriculture through crop diversification: Adaptive management for environmental change. BioScience 61(3):183–193

Magurran AE (2004) Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell, Oxford, United Kingdom

Mahmud W, Rahman SH, Zohir S (1994) Agricultural growth through crop diversification in Bangladesh. Food policy in Bangladesh working paper, no. 7. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, D.C

Makate C, Wang R, Makate M, Mango N (2016) Crop diversification and livelihoods of smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe: adaptive management for environmental change. SpringerPlus 5(1):1135

Malapit HJL, Sraboni E, Quisumbing AR, Ahmed AU (2018) Intrahousehold empowerment gaps in agriculture and children's well-being in Bangladesh. Dev Policy Rev 37:176–203

Malapit Hazel J, Sraboni Esha, Quisumbing Agnes R, Ahmed Akhter U (2019) Intrahousehold empowerment gaps in agriculture and children’s well-being in Bangladesh. Development Policy Review 37(2):176–203

McCord PF, Cox M, Schmitt-Harsh M, Evans T (2015) Crop diversification as a livelihood strategy within semi-arid agricultural systems near Mount Kenya. Land Use Policy 42:738–750

McKinley J, Adaro C, Rutsaert P, Pede VO, Sander BO (2018) Gender differences in climate change perception and adaptation strategies: the case of three provinces in Vietnam’s Mekong River Delta. In Gender dimension of climate change research in agriculture: case studies in Southeast Asia. Wageningen, the Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Available at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/76928/CCAFS%20Info%20Note_PIRCCA.pdf. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Metzel J, Ateng B (1993) Constraints to diversification in Bangladesh: a survey of farmers' views. Bangladesh Dev Stud 21(3):39–71 Crop Diversification in Bangladesh

Mottaleb KA, Sonobe T (2011) An inquiry into the rapid growth of the garment industry in Bangladesh. Econ Dev Cult Chang 60(1):67–89

Mullahy J (2015) Multivariate fractional regression estimation of econometric share models. J Econom Methods 4(1):71–100

Osmani SR, Ahmed T, Hossain N, Huq S (2016) Strategic review of food security and nutrition in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: World Food Programme (WFP). https://www.wfp.org/content/food-and-nutrition-security-bangladesh. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Owen G (2020) What makes climate change adaptation effective? A systematic review of the literature. Glob Environ Chang 62:102071

Passarelli S, Mekonnen D, Bryan E, Ringler C (2018) Evaluating the pathways from small-scale irrigation to dietary diversity: evidence from Ethiopia and Tanzania. Food Secur 10(4):981–997

Perez C, Jones EM, Kristjanson P, Cramer L, Thornton PK, Fuerch W, Barahona C (2015) How resilient are farming households and communities to a changing climate in Africa? A gender-based perspective. Glob Environ Chang 34:95–107

Quisumbing AR, Roy S, Njuki J, Tanvin K, Waithanji E (2013) Can dairy value-chain projects change gender norms in rural Bangladesh? Impacts on assets, gender norms, and time use. IFPRI Discussion Paper 1311. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/127982. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Rabbani G, Rahman A, Mainuddin K (2013) Salinity induced loss and damage to farming households in coastal Bangladesh. Int J Global Warming 5(4):400–415

Rahman S (2000) Women’s employment in Bangladesh agriculture: composition, determinants and scope. J Rural Stud 16(4):497–507

Rahman S (2008) Determinants of crop choices by Bangladeshi farmers: A bivariate probit analysis. Asian J Agric Dev 5:30–14

Rahman S (2009) Whether crop diversification is a desired strategy for agricultural growth in Bangladesh. Food Policy 34(4):340–349

Ruane AC, Major DC, Yu WH, Alam M, Hussain SKG, Khan AS, Hassan A, Al Hossain BMT, Goldberg R, Horton RM, Rosenzweig C (2013) Multi-factor impact analysis of agricultural production in Bangladesh with climate change. Glob Environ Chang 23(1):338–350

Ruel MT, Quisumbing AR, Balagamwala M (2018) Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: what have we learned so far? Global Food Secur 17(June):128–153

Safilios-Rothschild C (1990) Socio-economic determinants of the outcomes of women’s income-generation in developing countries. In: Stichter S, Parpart J (eds) Women, employment and the family in the international division of labour. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Seymour G (2017) Women’s empowerment in agriculture: implications for technical efficiency in rural Bangladesh. Agric Econ 48(4):513–522

Seymour G, Masuda YJ, Williams J, Schneider K (2019) Household and child nutrition outcomes among the time and income poor in rural Bangladesh. Global Food Secur 20:82–92

Sibhatu KT, Krishna VV, Qaim M (2015) Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(34):10657–10662

Smit B, Skinner MW (2002) Adaptation options in agriculture to climate change: a typology. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 7:85–114

Springmann M, Mason-D'Croz D, Robinson S, Tara G, Charles H, Godfray J, Gollin D et al (2016) Global and regional health effects of future food production under climate change: a modelling study. Lancet 387 no. 10031

Sraboni E, Quisumbing AR (2018) Women’s empowerment in agriculture and dietary quality across the life course: evidence from Bangladesh. Food Policy 81:21–36

Sraboni E, Malapit HJ, Quisumbing AR, Ahmed AU (2014) Women’s empowerment in agriculture: what role for food security in Bangladesh? World Dev 61:11–52

Tittonell P, Klerkx L, Baudron F, Félix GF, Ruggia A, van Apeldoorn D, Dogliotti S, Mapfumo P, Walter AHR (2016) Ecological intensification: local innovation to address global challenges. In: Lichtfouse E (ed) Sustainable agriculture reviews. Springer Science+Business Media, Berlin, pp 1–34

Twyman J, Green M, Bernier Q, Kristjanson P, Russo S, Tall A, Ampaire E, Nyasimi M, Mango J, McKune S, Mwongera C, Ndourba Y (2014) Gender and climate change perceptions, adaptation strategies, and information needs preliminary Results from four s ites in Africa. CCAFS Working Paper no. 83. CGIAR research program on climate change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Copenhagen, Denmark. Available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org (6) (PDF) Adaptation Actions in Africa: Evidence that Gender Matters. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280573500_Adaptation_Actions_in_Africa_Evidence_that_Gender_Matters. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

USAID (2012) Climate change adaptation plan. Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1865/Agency%20Climate%20Change%20Adaptation%20Plan%202012.pdf. Accessed: July 30 2020

USAID (2018) Bangladesh: nutrition profile. United States Agency for International Development, Washington, D.C. Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/Bangladesh-Nutrition-Profile-Mar2018-508.pdf. Accessed: June 10 2019

Vandermeer J, van Noordwijk M, Anderson J, Ong C, Perfecto I (1998) Global change and multi-species agroecosystems: Concepts and issues. Agric Ecosyst Environ 67:1–22

Villamor GB, Afiavi Dah-gbeto P, Bell A, Pradhan U, van Noordwijk M (2015) Gender-specific spatial perspectives and scenario building approaches for understanding gender equity and sustainability in climate-smart landscapes. In: Minang PA, van Noordwijk M, Freeman OE, Mbow C, de Leeuw J, Catacutan D (eds) Climate-smart landscapes: multifunctionality in practice. World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), Nairobi, pp 211–225

Werners SE, Incerti F, Bindi M, Moriondo M, Cots F (2007) Diversification of agricultural crops to adapt to climate change in the Guadiana River Basin. In Proceedings from the international conference on climate change, Hong Kong, p. 115. Available at: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/45091160/Diversification_of_Agricultural_Crops_to20160426-19153-zbwwuw.pdf?1461656542=&responsecontentdisposition=inline%3B+filename%3DDiversification_of_agricultural_crops_to.pdf&Expires=1605525207&Signature=Ph14ZnaI7Vpar7nFk56Bd1e8wzj~M53vfHZKswUQVP0j-QnQR9Jpolzu9ttQ50h~lt8Cfg1OlUCBmvF3CxuEy9UNIgwlAQfKRNFr6dZDd4GeggIAkieRmoT9LuBWRdr1SWHV6M1cNvqR98AhkSzOVZFgWsIpCC6Xt~74LEnX-sfg75x-1Z529JO3HCHikhudM21WY2rEtES0-Jv4kw5bt14vlPmDg7c~lb2neks~tYuo0Cumx~OVmkaNSridI-BZho4DCB31Yrq-QHSUbaSHluH6tyHvz7TNGTygWI8QpFTWPU-9U7aUuP3j8yBxeCMnSiSpJZibc4eKsgcetXyw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Wu J, Segerson K (1995) The impact of policies and land characteristics on potential groundwater pollution in Wisconsin. Am J Agric Econ 77(4):1033–1047

Funding

This work was undertaken as part of the Gender, Climate Change and Nutrition Integration Initiative (GCAN) funded by USAID and is associated with the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), which is carried out with support from CGIAR Fund Donors and through bilateral funding agreements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ADP, GS, EB, and PB developed the outline and provided input to the writing of the manuscript.

GS and PB prepared the relevant dataset.

ADP performed the econometric modeling.

ADP, GS, and EB performed the analysis of results.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

We assume that n producers have equal access to k available inputs I with price wk which can be combined to obtain output quantities Qj for 1….J crops that are sold at price pj. The production technology farmers use to produce each crop can be represented by a Cobb-Douglas functional form:

Where \( {G}_n=\left({\prod}_{\lambda =1}^{\Lambda}{G}_{\lambda}^{\varphi_n}\right) \) is a multiplicative combination of Λ household-specific features that affect the level of output Q.

Following Beattie and Taylor (1993) we write the indirect profit function ensuing from eq.A1 to express the maximum per-hectare profit as a function of the output and input prices.Footnote 7

where:γ = 1 − ∑kαk.

Equation A2 can be linearized by taking the log:

and rewritten as

where:

The acreage cost function is a linear combination of l household-specific factors that can affect the monetary and non-monetary costs of managing alternative crop allocations: Cn = ∑lcnl.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De Pinto, A., Seymour, G., Bryan, E. et al. Women’s empowerment and farmland allocations in Bangladesh: evidence of a possible pathway to crop diversification. Climatic Change 163, 1025–1043 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02925-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02925-w