Abstract

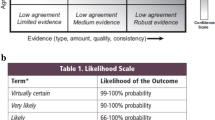

Tackling climate change is a global challenge and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the organisation charged with communicating the risks, dangers and mechanisms underlying climate change to both policy makers and the general public. The IPCC has traditionally used words (e.g., ‘likely’) in place of numbers (‘70 % chance’) to communicate risk and uncertainty information. The IPCC assessment reports have been published in six languages, but the consistency of the interpretation of these words cross-culturally has yet to be investigated. In two studies, we find considerable variation in the interpretation of the IPCC’s probability expressions between the Chinese and British public. Whilst British interpretations differ somewhat from the IPCC’s prescriptions, Chinese interpretations differ to a much greater degree and show more variation. These results add weight to continuing calls for the IPCC to make greater use of numbers in its forecasts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The IPCC translates its reports into the six official languages of the United Nations (English, Chinese, Arabic, French, Spanish, Russian). There have, however, been a number of additional, unofficial, translations of the IPCC reports (see http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/publications_and_data_reports.shtml#6)

In the present studies, we did not provide participants with the numerical ranges specified by the IPCC, as we were interested in participants’ natural interpretations. Moreover, in such short studies, experimental pragmatics might ensure consistency with IPCC prescriptions, but in the context of reading hundreds of pages of technical reports, a closer fit with natural interpretations is likely to be highly beneficial. The lack of consistency between the IPCC’s guidelines and participants’ interpretations when provided with the information in the IPCC’s typical format (Budescu et al. 2009, 2012) demonstrates this.

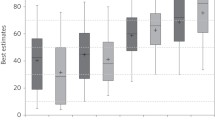

Although participants’ responses are on an interval scale, we chose to present medians and IQRs to maintain consistency with related research (e.g., Budescu et al. 2009). Given the interval nature of our data, however, we use parametric analyses in our inferential statistics.

All these results also hold if age is included as a covariate in the analysis, as is the case in Section 2.

These analyses were conducted through an ANOVA in which the effects were calculated sequentially, using Type 1 sum of squares, such that gender and educational attainment were added to the model before location, with age included as a covariate.

References

Beyth-Marom R (1982) How probable is probable? A numerical translation of verbal probability expressions. J Forecast 1:257–269

Box GEP (1954) Some theorems on quadratic forms applied in the study of analysis of variance problems: I. Effect of inequality of variance in the one-way classification. Ann Math Stat 25:484–498

Brun W, Teigen KH (1988) Verbal probabilities: ambiguous, context- dependent, or both? Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 41:390–404

Budescu DV, Wallsten TS (1985) Consistency in interpretation of probabilistic phrases. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 36:391–405

Budescu DV, Broomell S, Por H (2009) Improving communication of uncertainty in the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Psychol Sci 20:299–308

Budescu DV, Por H-H, Broomell SB (2012) Effective communication of uncertainty in the IPCC reports. Clim Chang 113:181–200

Davidson RA, Chrisman HH (1993) Interlinguistic comparison of International Accounting Standards: the case of uncertainty expressions. Int J Account 28:1–16

Davidson RA, Chrisman HH (1994) Translations of uncertainty expressions in Canadian accounting and auditing standards. J Int Account Audit Tax 3:187–203

Doupnik TS, Richter M (2003) Interpretation of uncertainty expressions: a cross- national study. Acc Organ Soc 28:15–35

Doupnik TS, Richter M (2004) The impact of culture on the interpretation of ‘in context’ verbal probability expressions. J Int Account Res 3:1–20

Fischer K, Jungermann H (1996) Rarely occurring headaches and rarely occurring blindness: is rarely = rarely? Meaning of verbal frequentistic labels in specific medical contexts. J Behav Decis Mak 9:153–172

Geall S (2011) Climate change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation. International Media Support. [Retrieved from https://s3.amazonaws.com/cd.live/uploads/content/file_en/4289/climatejournalism__1_.pdf March 26th, 2013]

Harris AJL, Corner A (2011) Communicating environmental risks: clarifying the everity effect in interpretations of verbal probability expressions. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 37:1571–1578

Harris AJL, Corner A, Hahn U (2009) Estimating the probability of negative events. Cognition 110:51–64

Howell DC (1997) Statistical methods for psychology, 4th edn. Wadsworth, Belmont

Hulme M (2010) Why we disagree about climate change: understanding controversy, inaction and opportunity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007) Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/syr/en/contents.html March 26th, 2013]

Lau L-Y, Ranyard R (1999) Chinese and English speakers’ linguistic expression of probability and probabilistic thinking. J Cross-Cult Psychol 30:411–421

Mastrandrea MD, Field CB, Stocker TF, Edenhofer O, Ebi KL, Held H, et al. (2010) Guidance note for lead authors of the IPCC fifth assessment report on consistent treatment of uncertainties. IPCC cross-working group meeting on consistent treatment of uncertainties, Jasper Ridge, CA. [retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/supporting-material/uncertainty-guidance-note.pdf August 14th, 2013]/

Patt A, Dessai S (2005) Communicating uncertainty: lessons learned and suggestions for climate change assessment. Compt Rendus Geosci 337:425–441

Sirota, M., & Juanchich, M. (2012). Risk communication on shaky ground. Science, 338, 1286-1287.

Smithson M, Budescu DV, Broomell SB, Por H-H (2012) Never say “not:” impact of negative wording in probability phrases on imprecise probability judgments. Int J Approx Reason 53:1262–1270

Teigen KH, Juanchich M, Riege AH (2013) Improbable outcomes: infrequent or extraordinary? Cognition 127:119–139

Wallsten TS, Budescu DV, Zwick R (1993) Comparing the calibration and coherence of numerical and verbal probability judgments. Manag Sci 39:176–190

Weber EU (1994) From subjective probabilities to decision weights: the effect of asymmetric loss functions on the evaluation of uncertain outcomes and events. Psychol Bull 115:228–242

Weber EU, Hilton DJ (1990) Contextual effects in the interpretations of probability words: perceived base rate and severity of events. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 16:781–789

Witteman C, Renooij S (2003) Evaluation of a verbal-numerical probability scale. Int J Approx Reason 33:117–131

Acknowledgments

We thank Melinda Soh, Jia Li, Lingxiao Guo, Yanmei Zhang, Qin Zhang, Qi Guan, Lina Bai and Zhen Xiao for assistance with data collection, Daniel Chu for assistance with translation, Tobias Gerstenberg for assisting with graphs and Nigel Harvey and Matthias Gobel for comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author contributions

AJLH conceived and designed the studies, and analysed the data. JX assisted in designing the studies and oversaw the translation of materials into Chinese. AJLH, JX and XD ran Study 1. AJLH and XD ran Study 2. AJLH and AC wrote the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 39 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, A.J.L., Corner, A., Xu, J. et al. Lost in translation? Interpretations of the probability phrases used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in China and the UK. Climatic Change 121, 415–425 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0975-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0975-1