Abstract

The frequently observed discrepancy between estimations of N2O emissions at regional or global scale based either on field data or inventories (bottom-up) or on direct atmospheric observations (top-down) suggests that riparian areas and river surfaces play a significant role as hot spots of emission. We developed a modeling procedure to assess N2O emissions occurring during the transfer of water masses from the subroot water pool of the watershed to the outlet of the river drainage network, including their passage through riparian wetlands. The model was applied to three river basins of increasing size located in the sedimentary geological area of the Paris basin (France) and validated by its capability to predict river N2O concentrations and fluxes across the river–atmosphere interface. At the scale of the Seine watershed, indirect emissions, i.e. emissions linked to agricultural practices but occurring elsewhere than directly at the field plot, are estimated to represent approximately 20% of the direct emissions from the watershed soils, in good agreement with previous estimates based on empirical accounting approaches. Denitrification in riparian zones is responsible for the largest share of these indirect emissions. The model results are very sensitive to the value of the ratio of N2O versus (N2 + N2O), in the final products of denitrification in rivers and wetlands. By calibration on river N2O concentrations, a value of 0.015 ± 0.05 is proposed for this ratio, in agreement with recent studies. This represents the main uncertainty factor of the model. In basins with conditions prone to increasing the value of this ratio, higher proportions of indirect N2O emissions might possibly be observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Direct N2O emission from agricultural land is a major anthropogenic source of greenhouse gas affecting climate change (Myhre et al. 2013), as well as posing a threat to the stratospheric ozone layer (Ravishankara et al. 2009). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2006) guidelines based on data compiled by Bouwman (1996) and Bouwman et al. (2002) recommend estimating these direct emissions at approximately 1.25% of applied synthetic fertilizers and manure. However, lower emission factors (EF) have been reported under various regional contexts from temperate (Gabrielle et al. 2006) to Mediterranean climates (Cayuela et al. 2016). On the other hand, there is evidence that emission response to increasing N inputs is exponential rather than linear (Shcherbak et al. 2014). Thus, quantifying direct N2O emission from agriculture remains uncertain at both regional and global scales.

In addition to these direct agricultural emissions, “indirect” processes, occurring far away from agricultural fields, also contribute, but their estimation [roughly 0.75% of leached nitrogen according to IPCC (2006) guidelines, revised to 1.1% in the IPCC (2019) report] is still a subject of controversy. Using a top–down approach based on the observed N2O increase in atmospheric concentration (rather than the bottom–up approach extrapolating from land-based data as recommended by the IPCC), Crutzen et al. (2008) estimated that 3–5% of anthropogenically produced reactive nitrogen at the global scale is actually emitted as N2O, implying a much higher overall emission factor compared with the IPCC factor.

Other authors using top–down approaches at regional scales based on tall tower trace gas measurements (Corazza et al. 2011; Thomson et al. 2011; Griffis et al. 2013) came to the same conclusion. Later on, Davidson (2009) and Reay et al. (2012) tried to reconcile the top–down and bottom–up methodologies by considering that N2O emitted by recycled nitrogen, such as manure nitrogen, as well as emissions from nitrate-contaminated semi-natural environments, contributes more to global N2O emissions than agricultural soils themselves. Syakila and Kroeze (2011), revisiting the global nitrous oxide budget, confirmed that the observed increase in atmospheric N2O cannot be explained by inventories based on the current IPCC guidelines, highlighting the significance of poorly constrained indirect anthropogenic emissions linked to the nitrogen cascade.

There is in fact no comprehensive and formalized vision of the cascade of processes responsible for indirect N2O emissions. Systematic measurements at the landscape scale show the existence of N2O emission hot spots in wetlands and riparian areas, in places where nitrate-enriched groundwater comes into contact with the biogeochemically active upper soil layers (Clement et al. 2002; Oehler et al. 2007; Vilain et al. 2010, 2012; Anderson et al. 2014). However, given the limited areal extent of riparian wetlands, their contribution to agricultural N2O emission, though significant, was lower than direct emissions.

Rivers and streams appear as other hotspots of N2O emissions to the atmosphere. Garnier et al. (2009) and Outram et al. (2012) showed that surface waters in agricultural drainage networks are systematically oversaturated with respect to atmospheric concentration, particularly in small stream orders, showing that rivers in general and headwaters in particular are significant N2O emitters. Interestingly, domestic wastewater-impacted rivers are also major emitters (Garnier et al. 2007, 2009; Tallec et al. 2006). Beaulieu et al (2011) directly measured N2 and N2O emission using whole-stream 15NO3 -tracer experiments in 72 headwater streams draining different land-use types across the United States. Extrapolating their results, they concluded that river network emissions can represent about 10% of global anthropogenic N2O emissions. Turner et al. (2015) reported measurements of N2O fluxes across the water–atmosphere interface of streams of different Strahler order in the Mississippi basin and suggested that taking into account headwater streams (including episodic zero-order microflow stream channels or tile drain collectors) can more than double the agricultural N2O budget compared with bottom–up estimates based on IPCC guidelines.

River emission results from two processes: (i) degassing of N2O produced in soils and aquifers once groundwater reaches surface water, and (ii) in-stream production of N2O in oxygen-depleted sectors either in the water column or in the benthos, through both nitrification and denitrification (Mulholland et al. 2008). In contrast to the former, the latter processes are particularly significant in large river stretches and estuaries, as reported by Barnes and Owens (1999), Kroeze et al. (2005), Garnier et al. (2006, 2007, 2009), and Rodrigues et al. (2007).

Here we develop a comprehensive modeling framework embracing the whole N cascade from cropland to river waters in order to relate direct N2O emission from agricultural soils and the indirect processes listed above. Several mechanistic models have been developed to calculate N2O emissions from agricultural soil profiles, such as DNDC (Li et al. 1992; Beheydt et al. 2007), DayCENT (Parton et al. 1996, 2001; Del Grosso et al. 2005), NOE (Hénault et al. 2005), and STICS (Bessou et al. 2010). These models perform well for estimating emissions linked to given pedo-climatic context and agricultural practices, but their one-dimensional (vertical) character prevents them from assessing the landscape interactions responsible for indirect emissions. A number of models were developed to simulate nitrogen cycling at the landscape scale (see the review by Cellier et al. 2011): these tools are able to calculate nitrate transfers and associated N2O emissions through the different compartments of a small terrestrial landscape (typically 1–10 km2) at very fine spatial and temporal resolution, but they require a comprehensive and detailed data set on topography, hydrology, soil conditions, and farming practices.

Our approach requires far fewer data; it is closely connected to our modeling approach of nitrate elimination at the river–watershed interface (Billen et al. 2018). It is applied here to three temperate watersheds of increasing size, characterized by intensive agriculture: the Orgeval, the Haut Loir, and the Seine. The purpose of this work is to assess, using a coherent modeling procedure, the share and location of the different processes responsible for indirect N2O emissions in the land- and waterscape of agricultural basins of different sizes.

Modeled watersheds

The Orgeval is a small catchment (106 km2) in the Brie Laitière agricultural region located approximately 70 km east of Paris, nested in the Seine basin. Agricultural land, mainly devoted to cereal cropping, occupies 82% of the total area, while forests represent 17%, hence with very few grasslands and livestock left. Active riparian wetlands, defined as potential wetlands covered by grasslands or forests, represent 3.2% of the watershed. In all, 90% of the agricultural area is equipped with tile drains. The geological, hydrological, and land use features are described in detail by Garnier et al. (2014, 2016). Direct N2O emissions from the main cropping systems have been measured with manual and automatic chambers by Vilain et al. (2010, 2011, 2012) and Benoit et al. (2014, 2015a, b) for 10 years. Annual mean values integrated over crop rotation cycles ranged between 0.65 and 0.9 kgN/ha/yr. N2O concentrations in groundwater (piezometers) and surface water have been regularly measured in parallel (Vilain et al. 2011; Garnier et al. 2007, 2009). The basin is part of the OZCAR network of experimental watersheds (https://ozcar-ri.prod.lamp.cnrs.fr/oracle/).

The Haut Loir basin (3600 km2, upstream from Chateaudun) drains two distinct agricultural regions with contrasting geological and pedological substrates. The western part of the basin is representative of the Perche region, with clayey soils, heavily tile-drained, and a dense tributary network, while the eastern part is representative of the Beauce region, with a very low river drainage density mainly fed by a deep groundwater system. Direct N2O emissions were regularly measured with manual chambers at two locations. Annual mean emission was approximately 1–2 kgN/ha/yr. The main crop rotations in the whole watershed and their N budget were recorded (see Billen et al. 2018).

N2O concentration in surface water, as well as emission fluxes at the water–atmosphere interface, were measured throughout the 2017–2018 period by Grossel et al. (in preparation).

The Seine watershed, upstream from Caudebec (73,500 km2, including the freshwater estuary), has been described in detail by Meybeck et al. (1998) and Flipo et al. (2019). Its land use comprises 57% cropland, 26% forest, 10% grassland, and 7% urban or artificialized areas. The current structure of its agricultural system is described in detail by Le Noë et al. (2017) and Billen et al. (2019). Direct and indirect N2O emissions were estimated by Garnier et al. (2009, 2019) using bottom–up methodologies. Numerous measurements of N2O concentrations in the drainage network are available. They show a clear stream order structure, with higher concentrations in headwaters, decreasing to near-saturation values in third- to fifth-order streams, then increasing again in higher-order rivers (Garnier et al. 2009).

The model described below was run on these three watersheds for three contrasting hydrological years: 2016, 2017, and 2018. The first is characterized by a relatively atypical flood in June, while the other two years present a more usual temperate regime, with high flow in winter and low flow from June to October. The average specific runoff over the 3 years was 175, 112, and 145 mm/yr for the Orgeval, Haut Loir, and Seine watersheds, respectively.

Model description

The model of N2O fluxes developed in this paper closely relies on the description of nitrate flow from cropland subroot zone to river outlet, including transfer through riparian wetlands, recently published by Billen et al. (2018). In brief, this model first assesses a fixed nitrate concentration to subroot water from each land use class of the basin, based on the N balance of typical crop rotations. This concentration is assigned to pre-calculated subsurface and base flow runoff. Unless tile drainage allows some fraction of the subsurface runoff to bypass riparian zones, the nitrate flow issued from the watershed has to cross an active denitrification area before reaching surface water. The resulting nitrate reduction that occurs there is calculated taking into account the extent of riparian wetlands in each elementary watershed, their potential denitrification rate, and the seasonal variations in temperature. Other processes affecting nitrate in the river drainage include algal uptake, water column, and benthic nitrification and denitrification as described in the RIVE model (www.fire.upmc.fr/rive), as well as inputs from urban point sources.

The same approach is considered here to model the corresponding flows of N2O. The model: (1) assigns a N2O concentration to subroot water for each land use class in the watershed; (2) assesses N2O production and emission in the riparian wetlands; and (3) calculates in-stream N2O production and the resulting emissions across the water–atmosphere interface (Fig. 1).

Principles of the model of N2O production and transfer through the land–river continuum. (Cbas, Crip and Criv stand for N2O concentration in the water phase of basin soil, riparian soil and river respectively; Sbas, Srip, Sriv are the suface area of watershed, riparian wetlands and river network.; Ebas, Erip, Eriv stand for the N2O emission from watershed soils, riparian wetlands and river surface, respectively. kvs is the gas transfer coefficient from soil to atmosphere; kr is the gas transfer coefficient from river water to the atmosphere)

N 2 O concentration in subroot water

Initialization of the model of N2O transfer requires an assessment of a representative N2O concentration to subroot water of each land use class considered in the watershed. Direct measurement of this concentration is technically extremely difficult. However, N2O concentration could be measured in groundwater collected from piezometer or groundwater resurgences, and showed large over-saturation with respect to atmospheric partial pressure. In fact, this level of over-saturation is the very driver of direct emission of N2O from soils to the atmosphere. As mentioned above, this latter flux is commonly measured using manual or automatic chambers, or can be estimated at an annual time scale through empirical relationships involving agricultural practices and climatic features, such as the one proposed by Garnier et al. (2019). An average N2O concentration of soil water (Cbas, in µgN-N2O/l) can therefore be associated with the average annual N2O direct emission from watershed soil to the atmosphere (Ebas, in mgN-N2O/m2/h), considering a simple soil water–atmosphere transfer coefficient (kvs):

where Ceq (mgN-N2O/m3) is the N2O concentration at equilibrium with the atmospheric partial pressure at the mean annual temperature, i.e. 0.33 mgN-N2O/m3 à 12 °C (Weiss and Price 1980). The parameter kvs (m/h) is defined as an average apparent ventilation coefficient between the soil water phase and the atmosphere. It can be calibrated on situations where both the flux of soil nitrous oxide emission and the soil water concentration are known. This is the case in a few spots in the investigated basins (Table 1), leading to a kvs value of approximately 0.0025 m/h.

N2O production and emission in riparian wetlands

During the water transfer from the watershed to the river across the riparian zone, the process of denitrification, while reducing nitrate concentration of the inflowing water discharge (Q, m3/s), also tends to increase its N2O concentration. The nitrate module of the Riverstrahler model (Billen et al. 2018) explicitly calculates the reduction of nitrate concentration (ΔCNO3denrip) due to denitrification. During this process, nitrate is partly converted into N2, and partly into N2O as an intermediate of denitrification. Although the share of denitrification flux converted to N2O can vary widely according to several factors, including availability of nitrate, organic matter, as well as pH (Weier et al. 1993; Saggar et al. 2013), the assumption is made of a constant fraction (pNden) expressing the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio. Because the value of this ratio is not very well constrained by empirical data, it is considered in the model as an adjustment parameter and a sensitivity analysis toward the chosen value is carried out (see”Discussion” section).

The rate of production of N2O (PN2Odenrip, mg/m3/h) through riparian denitrification can thus be estimated from the corresponding nitrate concentration reduction (ΔCNO3denrip, mg/m3) and the discharge Q (m3/h) flowing through the riparian zone:

As a result of this additional N2O production, a new equilibrium is established in the riparian zone, with increased emission across the riparian soil–atmosphere interface (Erip, mgN-N2O/m2/h), at a rate that can be expressed as:

where kvs is the soil–atmosphere transfer coefficient defined above, and Crip is the average N2O concentration in the riparian zone (here considered as a perfectly mixed reactor).

This new equilibrium concentration (Crip) in the riparian zone can be calculated by considering the material balance equation between input and output of the water flux Q through the riparian reactor, considering production of N2O by specifically riparian processes (PN2Odenrip) as well as by nonspecifically riparian processes, the latter corresponding to the average N2O emission in the watershed soils and thus equal to kvs×Srip×(Cbas-Ceq)) (see Eq. 1):

where Srip (m2) is the area of the riparian zone in the element of watershed considered, and Cbas here is the average N2O concentration in soil water from the watershed resulting from non-riparian processes.

From Eq. 4 it follows that:

Or

This procedure also allows calculation of the emission flux from riparian soil to the atmosphere (Eq. 3), thus providing a complete budget of N2O in the riparian zone.

In-stream processes

Point sources of N2O linked to urban wastewater inputs must be considered in modeling N2O in the river network. Based on a number of surveys of N2O concentration in effluents from different types of wastewater treatment plants, as well as on detailed specific studies (Tallec et al. 2006, 2008), the model considers that wastewater inputs are at near saturation N2O concentration, except when a tertiary treatment of nitrification and/or denitrification treatment is involved, in which case the N2O concentration is 10 times the saturation level.

In-stream production of N2O can also occur by nitrification and denitrification in the river water column and in the benthic phase. These are part of the RIVE module of the Riverstrahler model, described in detail at www.fire.upmc.fr/rive, as well as by Garnier et al. (2006, 2007) for the special case of the lower Seine River. The same parameterization has been used in the present study. Regarding benthic processes, the calculation procedure used is the one resulting from the meta-model established by Billen et al. (2015), which allows calculation of the integrated benthic denitrification flux, from the calculation of the organic carbon deposition, together with the oxygen and nitrate concentrations in the water column. The resulting N2O emission flux from the benthos is assumed to be a fraction pNden of the integrated benthic denitrification.

Transfer of N2O through the water–atmosphere interface is classically represented by a relation linking the flux Eriv (mgN-N2O/m2/h) to the oversaturation of the water phase, with a transfer coefficient krN2O (m/h) depending on the flow velocity (v, m/h), the water column depth (dpth, m), and the slope (dimensionless) (Raymond et al. 2012), as done by Marescaux et al. (2018) (Weiss and Price 1980):

Results

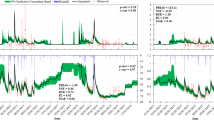

The model was first implemented at the scale of the small watersheds Orgeval and Haut Loir, for which the direct emissions estimated from measurements with static chambers on the main land use and crop rotations were available, thus allowing an estimation of an average subroot N2O concentration used as the main constraint variable of the model. The simulated N2O concentrations in the river network are calculated for different values (from 0 to 0.07) of the adjustable parameter pNden and compared with available observations at a number of stations (Fig. 2). A satisfactory agreement is obtained for a pNden fraction of approximately 0.015. Higher values lead to overestimation of N2O concentrations in all river stations. Lower values strongly underestimate the observations (Fig. 2).

Model-calculated time and space variations of N2O concentration in river water of a the Haut Loir basin and, b the Orgeval basin, for three values of the pNden parameter (representing the fraction of total denitrification emitted as N2O in riparian and stream processes). c Scatter plot of calculated versus observed river N2O concentrations for 3 values of pNden. The r2 of the correlation and the simulation RMSE (normalized to the mean) are indicated for each group of simulations. In all figures, red curves and points correspond to pNden = 0, blue is for pNden = 0.015, green for pNden = 0.07

The model also provides a complete budget of N2O emissions along the continuum from watershed soils to the outlet of the river network (Table 2) and can be mapped at the resolution used for the calculations, i.e. the detailed land-use and potential wetland data within each of the sub-watershed areas and 1-km stretches for the river network (Fig. 3).

In the case of the Haut Loir basin, a number of direct measurements of the emission flux of N2O across the river–atmosphere interface are also available (Grossel et al., in preparation). They range between 0.002 and 0.28 mgN/m2/h (mean 0.11 mgN/m2/h), which fits reasonably with the model estimates of 0.08 mgN/m2/h on average at the same stations for pNden = 0.015.

These results confirm that riparian wetlands as well as river surfaces can indeed be seen as hotspots of N2O emission, with per-area rates of emission sometimes more than twice the average direct emissions from the dominant agricultural land areas in the watershed, depending on the particular structure of the land- and waterscape. However, owing to their somewhat limited share in the total watershed area, these areas contribute to only 2–6% and 0.8–-2%, respectively, of the total emissions. In other words, indirect emissions from riparian and river surfaces together in fact only represent 3–7% of the direct emissions from the soils. The Haut Loir watershed, because of its lower relative areas of wetlands, has the lowest indirect emissions.

The model was also implemented at the scale of the much larger Seine watershed, using the estimates of N2O emission from cropland, grassland, and forest in the different agricultural regions made by Garnier et al. (2019) based on the record of fertilization practices (Le Noë et al. 2017) and regional climate data. Land use was geographically distributed based on Corine Land Cover, and the riparian wetlands were defined from the map of potential wetlands established on the basis of a topographical index (Curie et al. 2007; Berthier et al. 2014; https://geowww.agrocampus-ouest.fr/web/?p=1538), as described by Billen et al. (2018).

The calculated average N2O concentrations for different values of the pNden parameter were compared with those measured since 2012 in water from different Strahler orders (Fig. 4). Some unpublished measurements available in springs or in piezometers were also used for this comparison, the latter being referred to as “zero order,” the former as “subroot.” The measurements collectively show a U-shaped distribution of concentrations versus stream orders (see also Garnier et al. 2009 and Marescaux et al. 2018). The high concentrations at zero order (or subroot water) rapidly decrease with increasing stream orders, down to near saturation levels at order 3–5. N2O concentration increases again at higher orders. This U-shaped distribution is well reproduced by the model, which, however, predicts, on average, larger concentrations in riparian waters and headwaters; this quickly tends toward saturation once exposed to the rapid evasion processes across the water–atmosphere interface in surface river bodies. In-stream processes, fostered by increased point sources of organic pollution, are responsible for the further increase in N2O concentration at higher stream order. The results obtained by simulating N2O distribution with different values for the N2O/(N2O + N2) denitrification ratio (pNden) show again that a value of about 0.015 is the maximum compatible with available observations at the scale of the whole watershed (Fig. 4). A full map of N2O emissions from soils, riparian wetlands, and rivers in the Seine basin, similar to that shown in Fig. 3, can be viewed at address: https://doi.org/10.26047/PIREN.data.N2O.2019.

Model-calculated average N2O concentration in watershed and riparian water, as well as in surface water of different Strahler streams. Comparison with available measurements carried out in the Seine basin since 2012 (Garnier et al. 2009; Marescaux et al. 2018 and unpublished data). The level of N2O saturation with respect to atmospheric concentration for two temperatures is also indicated (blue dotted lines: 0.36 µgN-N2O at 10 °C, 0.21 µgN-N2O at 25 °C)). b Scatter plot of calculated versus observed N2O concentrations for 3 values of the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio (pNden). The r2 of the correlation and the simulation RMSE (normalized to the mean) are indicated for each group of simulations. In both figures, red curves and points correspond to pNden = 0, blue is for pNden = 0.015, green for pNden = 0.07

The complete budget of direct and indirect N2O emission at the scale of the Seine watershed shows that riparian emissions represent 17% of direct watershed emissions, while stream surface emission accounts for only 4%. Thus, indirect emissions represent almost 20% of total watershed emissions (Table 2).

Discussion

The approach developed in this paper pursues the attempt initiated by the introduction of a module of riparian denitrification in the Riverstrahler model (Billen et al. 2018) for describing the N cascade along the continuum from watershed soils to the river outlet within a coherent modeling framework. The model proposed is constrained by the direct N2O emissions from the different land use classes of watershed soils, assumed to be known on a yearly average basis, from either empirical measurements, using e.g. static chambers, or another independent modeling approach such as, for instance, the empirical relationship linking annual N2O emission to fertilizer inputs and climate data established by Garnier et al. (2019) based on data from the literature. From this mean annual direct N2O emission value, the average N2O concentration in groundwater and subsurface runoff is calculated using a simple empirically calibrated transfer coefficient. Riparian denitrification is first calculated by the model in terms of nitrate reduction, based on the hydrological behavior of each sub-basin and on a temperature-dependent denitrification potential of riparian wetlands, the extension of which is defined by topographic information. A fraction pNden of this denitrification is assumed to be converted into N2O, which allows the model to calculate both the enhanced emission from riparian areas and the N2O concentration flowing into surface water. Within the drainage network, the model calculates the in-stream N2O production by benthic and water column processes, including nitrification and denitrification, as well as transfer across the water–atmosphere interface. The model is validated by its capability to predict the distribution of N2O concentration in river water at different places in the river network, as well as the order of magnitude of N2O emission fluxes at the river–atmosphere interface.

The model involves the calibration of two parameters, the soil–atmosphere transfer coefficient (kvs) and the fraction of denitrification emitted as N2O versus N2 (pNden). The meaning and value chosen for these two parameters requires some discussion.

N2O emission by soils is the result of complex and episodic processes, depending on highly transient conditions in a relatively heterogeneous medium (Saggar et al. 2013). This explains the difficulties in measuring and modeling them. The model approach developed here does not intend to describe these processes; it starts from the knowledge of annual emissions, which can be assessed either by in situ measurements or by using an empirical modeling approach (e.g., Garnier et al. 2019) and considers that the soil water pool that generates runoff is buffered to the extent that its average N2O concentration reflects the integrated soil N2O production processes. A soil–atmosphere transfer coefficient (kvs, in m/h) is calibrated on local situations where both the annual N2O emission flux from the soil and the average N2O concentration in the soil water pool are known. The emission values found in two such situations, in the Haut Loir and Orgeval basins, are consistently about 0.0025 m/h (Table 1). Combined with the mean runoff rate (100–270 mm/yr), these values imply that no more than 1–2% of the N2O flux produced in the soil is transferred to the hydrosphere rather than to the atmosphere. This contribution to the indirect emissions is thus somewhat limited.

The larger contributor to indirect emissions, therefore, consists of denitrification processes during the transfer of water from soils to the outlet of the river system, including riparian zones and the rivers themselves. The model calculates these processes by mechanistic modules, well established and validated by their capacity to correctly simulate nitrate and ammonium concentrations (Billen et al. 2018) with, however, one additional calibrated parameter (pNden) representing the fraction of N2O emitted during nitrate reduction through denitrification. This fraction is assumed to be constant in space and time for rivers and riparian wetlands.

N2O emission from denitrification results from an imbalance between the rate of NO3− reduction to N2O and its further reduction into N2. Decreased pH (Rochester 2003; Simek et al. 2002; Simek and Cooper 2002) or increased temperature (Benoit et al. 2015a, b) has been shown to result in higher N2O/(N2 + N2O) ratios in agricultural soils. The review by Rochester (2003) of several studies, as well as the data of Hénault et al. (2005), suggests a consistent relationship between this ratio and the pH, starting at values close to 0.01 at pH 7–8 and increasing up to 0.75 at pH 4–5. The problem with this relationship is that it was established based on laboratory studies in which the pH was manipulated. Only two results included in the relationship of Rochester (2003) come from direct field measurements: they both show a N2O/(N2 + N2O) ratio of 0.01 at a pH of 5.8 and 8.2, respectively. Simek et al. (2002) emphasized the point that the imbalance of microbial or enzymatic activities leading to N2O emission during denitrification can be transient until the readjustment of the rates of the two enzymatic processes (nitrate and N2O reductions) or the adaptation of the microbial consortium. N2O emission can therefore be a transient process linked to changes in pH or temperature rather than controlled by constant conditions of pH and temperature. We therefore limited our literature search to studies reporting pNden values based on measurements carried out under field conditions, i.e., without manipulation of the soil samples, either using 15 N-labelled fertilizer tracing, acetylene block technique on entire core samples or the results of emission chambers combined with estimation of denitrification. Even so, the range of values reported for the N2O/(N2 + N2O) ratio is considerable, varying from less than 0.01 to 0.6, without a clear relationship to pH or any other environmental variables (Denmead et al. 1979; Rudaz et al. 1999; Rochester 2003; Clement et al. 2002; Oehler et al. 2007; Scheer et al. 2009; Autret et al. 2019).

The review by Schlesinger (2009), distinguishing records of N2O/(N2 + N2O) for different types of ecosystems from agricultural soils, soils under natural vegetation or freshwater wetlands shows that the latter (0.08 ± 0.02) are typically much lower than the formers (0.37 ± 0.03 and 0.49 ± 0.07), as also shown by Beaulieu et al (2011). In a more recent paper, Butterbach-Bahl et al (2013) brought arguments showing that part of the data gathered by Schlesinger (2009), based on the use of the acetylene block technique, are subject to a systematic underestimation of N2 production by denitrification, leading to overestimation of the nitrous oxide ratio. Discarding these data leads to an average N2O/(N2 + N2O) ratio of 0.016 ± 0.04 for wetlands and rivers (based however on 5 measurements only). The measurements by Beaulieu et al (2011) obtained by in situ 15 N tracing across 53 US rivers and streams, ranged from 0.0004 to 0.056, with an interquartile range between 0.003 and 0.01.

The pNden value selected in our model calculations (0.015) is in exactly the same range. Figures 2 and 4 show the sensitivity of the model results to the value of this parameter. A more detailed analysis of the model response in terms of riparian and riverine emissions is shown for the case of the Seine watershed in Fig. 5. For pNden set to zero, the emission of riparian wetlands corresponds to the background soil processes, similar to the average of those direct emissions occurring in the watershed, while river indirect emissions consist of the evasion of N2O transferred from watershed soils to surface waters. At increasing pNden values, additional emission occurs from both riparian wetlands and river surfaces precisely due to denitrification processes occurring there. For a pNden value of approximately 0.015, the calculated emissions fit the observed distribution of river concentrations and emission fluxes. Higher values of pNden, e.g., 5 to 10 times higher (0.07—0.15), would clearly result in much higher estimates of indirect N2O emissions by riparian zones and river networks, which would reach values close to the watershed direct emissions themselves. However, such values are not supported by empirical observations of N2O concentration and emission rates available in the investigated watersheds.

The estimate of indirect N2O emissions obtained with the model for the Seine watershed is consistent with previous figures published by Garnier et al. (2009) Marescaux et al. (2018) based on empirical budgeting approaches (Table 3). They do not contradict the default parameters suggested in the IPCC guidelines. However, our estimate of indirect emissions in the Seine watershed does not take into account the possible contribution of ponds, lakes, and other stagnant water bodies.

Our estimated contribution of indirect emissions to total emissions from the Seine watershed is much lower compared with those reported by Turner et al. (2015) for the Mississippi. Our work is based on two different watersheds (Orgeval nested in the Seine basin) sharing the same geological substrate, both characterized by carbonate-rich sedimentary rocks. We cannot exclude that under other contexts and, in particular, in more acidic soils and waters, different values of pNden would apply and lead to much higher N2O emission in both river and riparian wetlands.

Conclusion

The modeling approach developed in this paper offers a coherent framework to model direct and indirect N2O emissions at the scale of the whole continuum from agricultural soils to river system. Its application to three watersheds of increasing size, from a few hundred to nearly 100,000 km2 in a temperate climate and sedimentary rock context, confirms the view that, in spite of high N2O emission rates per surface area in riparian wetlands and headwater streams, indirect emissions represent barely 20% of direct soil emissions when expressed at the scale of the whole watershed area. The largest part of these indirect emissions occurs in riparian areas where nitrate leached from the watershed soils undergoes partial denitrification. Headwaters receiving oversaturated groundwater from the watershed are also significant emitters. Downstream in the large river network, in-stream processes, possibly amplified by point source inputs, may contribute to enhanced emissions through the river–atmosphere interface.

References

Anderson TR, Goodale CL, Groffman PM, Walter MT (2014) Assessing denitrification from seasonally saturated soils in an agricultural landscape: a farm scale mass-balance approach. Agr Ecosyst Environ 189:60–69

Autret B, Mary B, Gréhan E, Ferchaud F, Grandeau G, Rakotovololona L, Bertrand M, Beaudoin N (2019) Can alternative cropping systems mitigate nitrogen losses and improve GHG balance? Results from a 19-yr experiment in Northern France. Geoderma 342:20–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.01.039

Barnes J, Owens NJP (1999) Denitriifcation and N2O concentrations in the Humber Estuary, UK and adjacent coastal zones. Mar Poll Bull 37:247–260

Beaulieu JJ, Tank JL, Hamilton SK, Wollheim WM, Hall RO, Mulholland PJ, Peterson BJ, Ashkenas LR, Cooper LW, Dahm CN, Dodds WK, Grimm NB, Johnson SL, McDowell WH, Poole GC, Valett HM, Arango CP, Bernot MJ, Burgin J, Crenshaw CL, Helton AM, Johnson LT, O’Brien JM, Potter JD, Sheibley RW, Sobota DJ, Thomas SM (2011) Nitrous oxide emission from denitrification in stream and river networks. PNAS 108:214–219. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011464108

Beheydt DPB, Sleutel S, Li C, Van Cleemput O (2007) Validation of DNDC for 22 long-term N2O field emission measurements. Atmos Environ 41:6196–6211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.04003

Benoit M, Garnier J, Anglade J, Billen G (2014) Nitrate leaching from organic and conventional arable crop farms in the Seine Basin (France). Nutrient Cycling in Agrosystems. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-014-9650-9

Benoit M, Garnier J, Billen G, Tournebize J, Gréhan E, Mary B (2015a) Nitrous oxide emissions and nitrate leaching in an organic and a conventional cropping system (Seine basin, France) Agriculture. Ecosystems and Environment 213(2015):131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.07.030

Benoit M, Garnier J, Billen G (2015b) Temperature dependence of nitrous oxide production of a luvisolic soil in batch experiments. Process Biochem 50:79–85

Berthier L, Bardy M, Chenu JP, Guzmova L, Laroche B, Lehmann S, Lemercier B, Martin M, Mérot P, Squividant H, Thiry E, Walter C (2014) Enveloppes des milieux potentiellement humides de la France métropolitaine. Notice d’accompagnement. Programme de modélisation des milieux potentiellement humides de France, Ministère d’Ecologie, du Développement Durable et de l’Energie. https://geowww.agrocampus-ouest.fr/web/?p=1538

Bessou C, Mary B, Leonard J, Roussel M, Grehan E, Gabrielle B (2010) Modelling soil compaction impacts on nitrous oxide emissions in arable fields. Eur J Soil Sci 61:348–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2010.01243.x

Billen G, Garnier J, Silvestre M (2015) A generic algorithm for modelling benthic nutrient fluxes in river systems. Int J Limnol 51:37–47. https://doi.org/10.1051/limn/2014030

Billen G, Ramarson A, Thieu V, Théry S, Silvestre M, Pasquier C, Hénault C, Garnier J (2018) Nitrate retention at the river–watershed interface: a new conceptual modeling approach. Biogeochemistry 139:31–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-018-0455-9

Billen G, Garnier J, Le Noë J, Viennot P, Gallois N, Puech T, Schott C, Anglade J, Mary B, Beaudoin N, Léonard J, Mignolet C, Théry S, Thieu T, Silvestre M, Passy P (2019) The Seine watershed water-agro-food system: long-term Trajectories of C, N and P metabolism. In: Labadie P, Lestel L (eds) Flipo N. The Seine River Basin, Handbook of Environemental Chemistry

Bouwman AF (1996) Direct emissions of nitrous oxide from agricultural soils. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 46:53–70

Bouwman AF, Boumans LJM, Batjes NH (2002) (2002) Modeling global annual N2O and NO emissions from fertilized fields. Global Biogeochem 16:1080. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GB001812

Butterbach-Bahl K, Baggs EM, Dannenmann M, Kiese R, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S (2013) Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: how well do we understand the processes and their controls? Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20130122. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0122

Cayuela ML, Aguilera E, Sanz-Cobena A, Adams DC, Abalos D, Barton L, Ryals R, Silver WL, Alfaro MA, Pappa VA, Smith P, Garnier J, Billen G, Bouwman L, Bondeau A, Lassaletta L (2016) Direct nitrous oxide emissions in Mediterranean climate cropping systems: emission factors based on a meta-analysis of available. AEE. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.10.006

Cellier P, Durand P, Hutchings N, Dragosits U, Theobald M, Drouet JP, Oenema O, Bleeker A, Breuer L, Dalgaard T, Duretz S, Kros J, Loubet B, Olensen J, Merot P, Viaud V, de Vries W, Sutton MA (2011) Nitrogen flows and fate in rural landscapes. In: Sutton MA, Howard CM, Erisman JW, Billen G, Bleeker A, Grennfelt P, van Grinsven H, Grizzetti B (eds) The European Nitrogen Assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 229–248

Corazza M, Bergamaschi P, Vermeulen AT, Aalto T, Haszpra L, Meinhardt F, O’Doherty S, Thompson R, Moncrieff J, Popa E, Steinbacher M, Jordan A, Dlugokencky E, Brühl C, Krol M, Dentener F (2011) Inverse modelling of European N2O emissions: assimilating observations from different networks. Atmos Chem Phys 11:2381–2398. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-2381-2011

Clément JC, Pinay G, Marmonier P (2002) Seasonal Dynamics of Denitrification along Topohydrosequences in Three Different Riparian Wetlands. J Environ Qual 31:1025–1037

Crutzen P, Mosier A, Smith K, Winiwarter W (2008) N2O release from agro-biofuel production negates global warming reduction by replacing fossil fuel. Atmos Chem Phys 8:389–395

Curie F, Gaillard S, Ducharne A, Bendjoudi H (2007) Geomorphological methods to characterizes wetlands at the scale of the Seine watershed. Sci Total Environ 375:59–68

Davidson EA (2009) The contribution of manure and fertilizer N to atmospheric nitrous oxide since 1860. Nat Geosci 2:659–662

Del Grosso SJ, Mosier AR, Parton WJ, Ojima DS (2005) DAYCENT model analysis of past and contemporary soil N2O and net greenhouse gas flux for major crops in the USA. Soil Tillage Res 83:9–24

Denmead OT, Freney JR, Simpson JR (1979) Nitrous oxide emission during denitrification in a flooded field. Soil Sci Soc Am J 43:716–718

Flipo N, Labadie P, Lestel L (2019) The Seine River Basin. Handb Environ Chem. https://doi.org/10.1007/698_2019_393

Gabrielle B, Laville P, Duval O, Nicoullaud B, Germon JC, C. Hénault C (2006) Process-based modeling of nitrous oxide emissions from wheat-cropped soils at the subregional scale. Glob Biogeochem Cycles. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GB002686

Garnier J, Cébron A, Tallec G, Billen G, Sebilo M, Martinez A (2006) Nitrogen behaviour and nitrous oxide emission in the tidal Seine River estuary (France) as influenced by human activities in the upstream watershed. Biogeochemistry 77:305–326

Garnier J, Billen G, Cébron A (2007) Modelling nitrogen transformations in the lower Seine river and estuary (France): impact of waste water release on oxygenation and N2O emission. Hydrobiologia 588:291–302

Garnier J, Billen G, Martinez A, Mounier E, Silvestre M, Vilain G, Toche F (2009) Nitrous oxide (N2O) in the Seine river and basin: observations and budgets. Agr Ecosyst Environ 133:223–233

Garnier J, Billen G, Vilain G, Benoit M, Passy P, Tallec G, Tournebize J, Anglade J, Billy C, Mercier B, Ansart P, Azougui A, Sebilo M, Kao C (2014) Curative vs. preventive management of nitrogen transfers in rural areas: Lessons from the case of the Orgeval watershed (Seine River basin, France). J Environ Manage 144:125–134

Garnier J, Le Noë J, Marescaux A, Sanz-Cobena A, Lassaletta L, Silvestre M, Thieu V, Billen G (2019) Long-term changes in greenhouse gas emissions from French agriculture and livestock (1852–2014): from traditional agriculture to conventional intensive systems. Sci Total Environ 660:1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.048

Griffis TJ, Lee X, Baker JM, Russelle MP, Zhang X, Venterea R, Millet DB (2013) Reconciling the differences between top-down and bottom-up estimates of nitrous oxide emissions for the US Corn Belt. Global Biogeochem Cycles 27(3):746–754. https://doi.org/10.1002/gbc.20066

Grossel, A. et al (in prep). Indirect emissions of nitrous oxide in a cropland watershed presenting contrasted hydrology in Central France.

Hénault C, Bizouard F, Laville P, Gabrielle B, Nicoullaud B, Germon JC, Cellier P (2005) Predicting in situ soil N2O emission using NOE algorithm and soil database. Glob Change Biol 2005(11):115–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00879.x

IPCC (2006). N2O Emissions from Managed Soils, and CO2 Emissions from Lime and Urea Application. AFOLU, vol.4. 54 pp (Chapter 11). , Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

IPCC (2019) Hergoualc’h, K., Akiyama, H., Bernoux, M., Chirinda, N., Del Prado, A., Kasimir, A., MacDonald, D., Ogle, S., Regina, K., van der Weerden, T., 2019. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Volume 5, Chapter 11: N2O emissions from managed soils, and CO2 emissions from lime and urea application. Technical Report. Technical Report 4–88788- 032–4, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Kroeze C, Dumont E, Sitzinger SP (2005) New estimates of global emissions of N2O from rivers and estuaries. Environ Sci 2:159–165

Le Noë J, Billen G, Garnier J (2017) How the structure of agro-food systems shapes nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon fluxes: the generalized representation of agro-food system applied at the regional scale in France. Sci Total Environ 586:42–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.040

Li C, Frolking S, Frolking TA (1992) A model of nitrous oxide evolution from soil driven by rainfall events: I. Model structure and sensitivity. J Geophys Res 97:9759–9776

Marescaux A, Thieu V, Garnier J (2018) Carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide emissions from the human-impacted Seine watershed in France. Sci Total Environ 643:247–259

Meybeck M, de Marsily G, Fustec E (eds) (1998) La Seine en son bassin. Fonctionnement écologique d’un système fluvial anthropisé. Elsevier, Paris, p 749

Mulholland PJ et al (2008) Stream denitrification across biomes and its response to anthropogenic nitrate loading. Nature 452(7184):202–205

Myhre G, Shindell D, Bréon FM, Collins W, Fuglesvedt J, Huang, J, Koch D, Lamarque JF, Lee D, Mendoza B, Nakajima T, Robock A, Stephens G, Takemura T, and Zhang H.(2013). Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing, in: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Solomon,S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K. B., Tignor, M., and Miller, H. L., Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA.

Oehler F, Bordenave P, Durand P (2007) Variations of denitrification in a farming catchment area. Agr Ecosyst Environ 120(2007):313–324

Outram F, Hiscock K (2012) Indirect nitrous oxide emissions from surface water bodies in a lowland arable catchment: a significant contribution to agricultural greenhouse gas budgets? Environ Sci and Technol 46:8156–8163

Parton WJ, Mosier AR, Ojima DS et al (1996) Generalized model for N2 and N2O production from nitrification and denitrification. Global Biogeochem Cycles 10:401–412

Parton WJ, Holland EA, Del Grosso SJ, Hartman MD, Martin E, Mosier AR, Ojima DS, Schimel DS (2001) Generalized model for NOx and N2O emissions from soils. J Geophys Res 106:17403–17419

Ravishankara AR, Daniel JS, Portmann RW (2009) Nitrous oxide (N2O): the dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st century. Science 326(5949):123–125

Raymond PA, Zappa CJ, Butman D, Bott TH, Potter J, Mulholland P, Laursen AE, McDowell WH, Newbold D (2012) Scaling the gas transfer velocity and hydraulic geometry in streams and small rivers. Limnol Oceanogr 2:41–53. https://doi.org/10.1215/21573689-1597669

Reay DS, Davidson EA, Smith KA, Smith P, Melillo JM, Dentener Fand Crutzen PJ (2012) Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nat Clim Change. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE1458

Rochester IJ (2003) Estimating nitrous oxide emissions from flood-irrigated alkaline grey clays. Aust J Soil Res 41:197–206

Rodrigues PPGW, Barnes J, Upstill-Goddard R (2007) Simulating estuarine nitrous oxide production by means of a dynamic model. Mar Poll Bull 54:164–172

Rudaz AO, Walti E, Kyburz G et al (1999) Temporal variation in N2O and N-2 fluxes from a permanent pasture in Switzerland in relation to management, soil water content and soil temperature. Agric Ecosyst Environmt 73:83–91

Saggar S, Jha N, Deslippe J, Bolan NS, Luo J, Giltrap DL, Kim DG, Zaman M, Tillman RW (2013) Denitrification and N2O:N2 production in temperate grasslands: processes, measurements, modelling and mitigating negative impacts. Sci Tot Envir 465:173–194

Scheer C, WassmannButterbach-Bahl RK et al (2009) The relationship between N2O, NO, and N-2 fluxes from fertilized and irrigated dryland soils of the Aral Sea Basin. Uzbekistan Plant Soil 314:273–283

Shcherbak I, Millar N, Robertson GP (2014) Global meta-analysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(25):9199–9204

Schlesinger WH (2009) On the fate of anthropogenic nitrogen. Proc National Acad Sci 106:203–208

Simek M, Cooper JE (2002) The influence of soil pH on denitrification:progress towards the understanding of this interaction over the last 50 years. Eur J Soil Sci 53:345–354

Simek M, Jisova L, Hopkins DW (2002) What is the so-called pH-optimum of denitrification? Soil Biol Biogeochem 34:1227–1234

Syakila A, Kroeze C (2011) The global nitrous oxide budget revisited. Greenh Gas Measure Manage 1:17–26

Tallec G, Garnier J, Billen G, Gousailles M (2006) Nitrous oxide emissions from secondary activated sludge in nitrifying conditions of urban wastewater treatment plants: effect of oxygenation level. Water Res 40:2972–2980

Tallec G, Garnier J, Billen G, Gousailles M (2008) Nitrous oxide emissions from denitrifying activated sludge of urban wastewater treatment plants, under anoxia and low oxygenation. Biores Technol 99:2200–2209

Thompson RL, Gerbig C, Rödenbeck C (2011) A Bayesian inversion estimate of N2O emissions for western and central Europe and the assessment of aggregation errors. Atmos Chem Phys 11:3443–3458. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-3443-2011

Turner PA, Griffis TJ, Lee X, BakerJM VRT, Wood JD (2015) Indirect nitrous oxide emissions from streams within the US Corn Belt scale with stream order. Proc Natl Acad Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1503598112

Vilain G, Garnier J, Tallec G, Cellier P (2010) Effect of slope position and land use on nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions (Seine Basin, France). Agr Forest Meteorol 150:1192–1202

Vilain G, Garnier J, Tallec G, Tournebize J (2011) Indirect N2O emissions from shallow groundwater in an agricultural catchment (Seine Basin, France). Biogeochemistry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-011-9642-7

Vilain G, Garnier J, Passy P, Silvestre M, Billen G (2012) Budget of N2O emissions at the watershed scale: role of land cover and topography (the Orgeval basin, France). Biogeosciences 9(1085–1097):2012

Weier KL, Doran JW, Power JF, Walters DT (1993) Denitrification and the dinitrogen nitrous-oxide ratio as affected by soil–water, available carbon, and nitrate. Soil Sci Soc Am J 571:66–72

Weiss RF, Price BA (1980) Nitrous oxide solubility in water and seawater. Mar Chem 8:347–359

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted within the framework of the HydroGES supported by the Agency for the Environment and Mastery of Energy (ADEME). The PIREN-Seine program and the Fédération Ile-de-France de Recherche pour l’Environnement (FIRE) are also acknowledged for their support. We are grateful to all the technical staff involved in field measurements discussed in this paper: Adeline Ayzac, Christian Lelay, Didier Laloua, Lionel Cottenot at URSols, Orléans, as well as Benjamin Mercier, Anun Matinez, and Sébastien Bosc at UMR Metis, Paris.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Responsible Editor: Adam Langley

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Billen, G., Garnier, J., Grossel, A. et al. Modeling indirect N2O emissions along the N cascade from cropland soils to rivers. Biogeochemistry 148, 207–221 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00654-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-020-00654-x