Abstract

Flavonoids are widely distributed as secondary metabolites produced by plants and play important roles in plant physiology, having a variety of potential biological benefits such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activity. Different flavonoids have been investigated for their potential antiviral activities and several of them exhibited significant antiviral properties in in vitro and even in vivo studies. This review summarizes the evidence for antiviral activity of different flavonoids, highlighting, where investigated, the cellular and molecular mechanisms of action on viruses. We also present future perspectives on therapeutic applications of flavonoids against viral infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Throughout human history, thousands of biologically active plants have been identified and used in medicine. Virtually all cultures around the world continue to rely on medicinal plants for primary health care. According to the World Health Organization report, about 80% of the world’s population depend on medicinal plants to satisfy their health requirements [30]. Furthermore, there are currently hundreds of modern drugs based on active compounds isolated from plants. Plants have the ability to produce a wide range of compounds including flavonoids, phytoalexins, lignans, and tannins, which are responsible for key functions in plant growth and development. Flavonoids or polyphenolics comprise the largest group of secondary metabolites found in vegetables, fruits, seeds, nuts, spices, stems as well as in red wine and tea (Table 1) [88]. These compounds are synthesized in response to various abiotic stress conditions such as ultraviolet radiation and play an important role as defense agents against plant pathogens and insects [9, 84]. The first evidence of a biological activity of flavonoids was reported by Albert Szent-Gyorgyii in 1938, who showed that citrus peel flavonoids prevent capillary bleeding and fragility associated with scurvy [109]. Since then, a broad spectrum of biological activities such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, anticancer, and neuroprotective has been described for flavonoids [40, 53, 65, 95, 137]. Research for antiviral agents isolated from plants started in 1950s, when the activity of 288 plants against influenza A virus was evaluated in embryonated eggs [14]. During the last 60 years, several plants and plant-derived compounds with antiviral properties were identified. In this article, we review the results of both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrating the antiviral activity of flavonoids, especially focusing on those classes of flavonoids that have been extensively investigated.

Chemistry of flavonoids

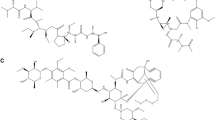

There are now more than 6000 varieties of flavonoids that have been structurally identified [35]. All these compounds comprise a flavan nucleus and a fifteen-carbon skeleton consisting of two benzene rings (A- and B-rings, as shown in Fig. 1) connected via a heterocyclic pyrene ring (C-ring, as shown in Fig. 1). Flavonoids are divided into several classes such as anthocyanidins, flavones, flavonols, flavanones, flavan, isoflavanoids, biflavanoids, etc (Table 1) [24]. The various classes of flavonoids differ in the level of oxidation and pattern of substitution of the pyrene ring, whereas individual compounds within the classes differ in the pattern of substitution of benzene rings. While in flavonoids the B-ring links to the C-ring at the C2 position, the B-ring of isoflavonoids is substituted at position C3 (Fig. 1). Biflavonoids comprise of two identical or non-identical flavonoid units conjoined through an alkyl- or alkoxy-based linker (Fig. 1).

In plants, flavonoids generally occur as aglycones, glycosides and methylated derivatives. They are biosynthesized through the phenylpropanoid pathway, transforming phenylalanine into 4-coumaroyl-CoA, which then enters the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway [32]. Depending on the plant species, a group of enzymes, such as hydroxylases and reductases, modify the basic flavonoid skeleton, resulting in the different flavonoid classes. Finally, transferases modify the flavonoid skeleton with sugar, methyl groups and acyl moieties. These modifications alter the solubility and reactivity of flavonoids [6]. A large body of evidence supports the role of light in the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis [156].

Antiviral activity of flavones

Flavones constitute a major class in the flavonoid family based on a 2-phenyl-1-benzopyran-4-one backbone. Natural flavones include apigenin, baicalein, chrysin, luteolin, scutellarein, tangeritin, wogonin and 6-hydroxyflavone. The antiviral activity of flavones is known from the 1990s, when it was showed that the simultaneous application of apigenin with acyclovir resulted in an enhanced antiviral effect on herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) in cell culture [92]. Apigenin is most commonly isolated in abundance from the family Asteraceae. The organic and aqueous extracts from Asteraceae plants with apigenin as a major compound were found to be active against HSV-1, poliovirus type 2 and hepatitis C virus (HCV) [85, 127]. Apigenin isolated from sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) showed a potent antiviral activity against adenoviruses (ADV) and hepatitis B virus in vitro [17]. Besides these DNA viruses, apigenin was found to exert antiviral effect against African swine fever virus (ASFV), by suppressing the viral protein synthesis and reducing the ASFV yield by 3 log [46]. Apigenin is also active against RNA viruses. For picronaviruses, it has been shown that apigenin is able to inhibit viral protein synthesis through suppressing viral IRES activity [82, 107]. Furthermore, apigenin affects enterovirus-71 (EV71) translation by disrupting viral RNA association with trans-acting factors regulating EV71 translation [153]. Shibata et al. [115] showed that apigenin has antiviral effect on HCV through the reduction of mature microRNA122, a liver-specific microRNA which positively regulates HCV replication.

Among flavones, baicalein and luteolin have been also extensively investigated with respect to their antiviral activity. Baicalein significantly reduced the levels of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) early and late proteins, as well as viral DNA synthesis, although it had no effect on viral polymerase activity [23, 31]. Baicalein impaired avian influenza H5N1 virus replication in both human lung epithelial cells and monocyte-derived macrophages by interfering with neuraminidase activity [116]. Other studies showed that oral administration of baicalein to BALB/c mice infected with influenza H1N1 virus decreased the lung virus titer and increased the mean time to death [139]. Similar effects were recorded on mice infected with Sendai virus [28]. These inhibitory effects in vivo were mediated by serum baicalin, a metabolite of baicalein which has a glucose residue [26]. Baicalin alone exerts its anti-influenza activity by modulating the function of NS1 protein, which down-regulates IFN induction [99]. Further studies indicated that baicalin can directly induce IFN-γ production in human CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells and act as a potent inducer of IFN-γ during influenza virus infection [19]. Recently, novel baicalein analogs with B-rings substituted with bromine atoms demonstrated extremely potent activity against influenza H1N1 Tamiflu-resistant virus, indicating that baicalein and its analogs can be favorable alternatives in the management of Tamiflu-resistant viruses [21]. In vitro replication of HIV-1 was suppressed by baicalin when infected cells were treated during the early stage of the virus replication cycle [66]. HIV-1 envelope protein was found to be the target site of baicalin’s antiviral action via the interference of interactions between the virus structural protein and specific host immune cells [75]. Baicalein and baicalin were also investigated against dengue virus (DENV). They exerted a significant virucidal effect on extracellular viral particles and interfered with different steps of DENV-2 replication [91, 148, 150]. In silico studies revealed that baicalein has strong binding affinity with DENV NS3/NS2B protein (-7.5 kcal/mol), and baicalin may interact closely with the virus NS5 protein at a binding affinity of -8.6 kcal/mol [47]. For baicalin, computational studies also showed a high binding affinity (-9.8 kcal/mol) against chikungunya virus (CHIKV) nsP3 protein, suggesting that baicalin can potentially interfere with CHIKV infection [114].

It was found that luteolin has antiviral effect on HIV-1 reactivation by blocking both clade B- and C-Tat-driven LTR transactivation [87]. Luteolin also showed significant inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation in cells [133]; it suppressed the activities of the immediate-early genes Zta and Rta by deregulating transcription factor Sp1 binding. Xu et al. [142] tested 400 highly purified natural compounds for inhibition of EV71 and coxsackievirus A16 infections and found that luteolin exhibited the most potent inhibition through disruption of viral RNA replication. Besides these antiviral activities, luteolin or luteolin-rich fractions showed antiviral effects against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), rhesus rotavirus, CHIKV and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) [33, 67, 94, 146].

Antiviral activity of flavonols

Flavonols are characterized by a 3-hydroxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one backbone. Among flavonols the antiviral effect of quercetin was the most extensively investigated. Early in vivo studies showed that oral treatment with quercetin protected mice from lethal Mengo virus [44, 125]. Furthermore, an enhanced protection was observed when quercetin was administered in combination with murine type I interferon (IFN) [125]. Quercetin also demonstrated a dose-dependent antiviral activity against poliovirus type 1, HSV-1, HSV-2, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in cell cultures [60, 83]. Epimedium koreanum Nakai, which contains quercetin as the major active component, has been shown to induce secretion of type I IFN, reducing the replication of HSV, Newcastle disease virus (NDV), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) in vitro, as well as influenza A subtypes (H1N1, H5N2, H7N3 and H9N2) in vivo [18]. Hung et al. [51] have suggested possible mechanisms whereby quercetin may exert its anti-HSV activity. They revealed that quercetin inhibits the infection of HSV-1, HSV-2 and acyclovir-resistant HSV-1 mainly by blocking viral binding and penetration to the host cell. They also reported that quercetin suppresses NF-κB activation, which is essential for HSV gene expression. Recent investigations also pointed out the antiviral activity of quercetin against a wide spectrum of influenza virus strains. It interacts with influenza hemagglutinin protein, thereby inhibiting viral-cell fusion [136]. In addition, in silico analysis revealed that quercetin may be a potential inhibitor of the neuraminidase of influenza A H1N1 and H7N9 viruses [79, 80]. Molecular docking analysis also found that quercetin may interact with HCV NS3 helicase, NS5B polymerase and p7 proteins [34, 86]. These results correlate with experimental studies showing the anti-HCV activity of quercetin through inhibition of NS3 helicase and heat shock proteins [4, 81]. Besides these viruses, the inhibitory activity of quercetin and its derivatives have been reported for other viruses, including ADVs, arthropod-borne Mayaro virus, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, canine distemper virus, JEV, DENV-2, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, and equid herpesvirus 1 [11, 16, 27, 38, 41, 59, 118, 149]. Quercetin also possesses anti-rhinoviral effects by inhibiting endocytosis, transcription of the viral genome and viral protein synthesis [37]. In mice infected with rhinovirus, quercetin treatment decreased viral replication and attenuated virus-induced airway cholinergic hyper-responsiveness [37].

Kaempferol is another flavonol extracted from different medicinal herbs. Kaempferol and its derivatives bearing acyl substituents have shown inhibitory activity against HCMV [89]. Kaempferol derivatives isolated from Ficus benjamina leaves were more effective against HSV-1 and HSV-2 than their aglycon form [145]. Kaempferol derivatives with rhamnose residue turned out to be potent inhibitors of the 3a channel of coronavirus, which is involved in the mechanism of virus release [112]. One of the kaempferol derivative, kaempferol 3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside, obtained from Zanthoxylum piperitum was shown to significantly inhibit the replication of influenza A virus in vitro [45]. Behbahani et al. found that kaempferol and kaempferol-7-O-glucoside have strong HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitory activity [5]. These compounds exerted their effects, at a concentration of 100 μg/ml, on the early stage of HIV replication in target cells. Recently, kaempferol-3,7-bisrhamnoside isolated from Chinese medicinal Taxillus sutchuenensis was shown to have potent in vitro activity on HCV NS3 protease function [144]. Antiviral activity of kaempferol on the influenza viruses H1N1 and H9N2 were mentioned in a study conducted by a group of researchers in South Korea. Mechanistic and structural studies suggested that the compound acts on the virus neuraminidase protein and specific functional groups are responsible for kaempferol’s efficacy [57]. A study comparing the antiviral activities of kaempferol and an isoflavone, daidzein, showed that kaempferol exerted more potent inhibitory activities on JEV replication and protein expression, than daidzein. JEV’s frameshift site RNA (fsRNA) has been proposed as the target site for kaempferol’s inhibitory activity against this flavivirus [152]. Seo et al. conducted a study comparing the potency of different classes of flavonoids against two RNA viruses, namely murine norovirus and feline calicivirus. Their findings demonstrated that, among the flavonoids tested, kaempferol exhibited the most potent inhibitory activity against these two viruses [113].

There are number of other flavonols and derivatives acting as antivirals. For example, sulfated rutin, which is modified from glycoside rutin, demonstrated significant activity against different HIV-1 isolates [123]. This compound inhibited HIV-1 infection by blocking viral entry and virus-cell fusion, likely by interacting with HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. Rutin at 200 μM concentration was shown to inhibit EV71 infection by suppressing the activation of MEK1-ERK signal pathway, which is required for EV71 replication of [129]. Rutin and fisetin also inhibited the replication of EV-A71 by affecting the enzymatic activity of the 3C protease [76]. Fisetin treatment caused a dose-dependent decrease in the production of CHIKV nonstructural proteins and inhibition of viral infection [73]. Moreover, Zandi et al. showed that DENV-2 RNA copy number was significantly reduced following addition of fisetin to infected cells [149]. Yu et al. found that myricetin may serve as chemical inhibitor of SARS-coronavirus because it affects the ATPase activity of the viral helicase [147].

Antiviral activity of flavans

Flavans are characterized by a 2-phenyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-chromene skeleton. These compounds include flavan-3-ols, flavan-4-ols and flavan-3,4-diols. Among flavan-3-ols, the antiviral activity of catechin and its derivatives epicatechin, epicatechin gallate, epigallocatechin (EGC), and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), which are found in tea, has been largely investigated [122]. Among different viruses studied as potential targets, influenza virus has received the most attention after an initial report by Nakayama et al. showing that tea catechins, particularly EGCG, are able to bind to the haemagglutinin of influenza virus, preventing its adsorption to Madin-Darby canine kidney cells [98]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that EGCG may be able to damage the physical properties of the viral envelope, resulting in the inhibition of hemifusion events between influenza virus and the cellular membrane [66]. Recently, Colpitts and Schang reported that EGCG competes with sialic acid for binding to influenza A virus, thereby blocking the primary low-affinity attachment to cells [22]. Another tea catechin, EGC, exerted the inhibitory effect on the acidification of endosomes and lysosomes, thereby reducing viral entry via clathrin-mediated endocytosis [52]. A structure-function relationship analysis of tea catechins revealed the important role of the 3-gallolyl group of the catechin skeleton for its antiviral activity [120]. The results also showed that modification of the 3-hydroxyl position significantly affected the antiviral activity. Catechin derivatives containing carbon chains at 3-hydroxyl position demonstrated potent anti-influenza activity in vitro and in ovo [121].

Several reports have demonstrated that tea catechins have an antiviral effect against HIV infection. Among tea catechins, EGCG is the most effective because it exerts its antiviral effect throughout several steps of the HIV-1 life cycle. It directly binds to CD4 molecules with consequent inhibition of gp120 binding, an envelope protein of HIV-1 [62, 134]. These studies identified Trp69, Arg59 and Phe43 of CD4 as potential sites for interaction with the galloyl moiety of EGCG. The same residues are involved in interaction with viral gp120 [135]. Furthermore, early studies from Nakane and Ono showed that EGCG and ECG were effective at inhibiting HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in vitro [96, 97]. Tillekeratne et al. modified the molecular structure of EGCG to determine the minimum structural characteristics necessary for HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibition [124]. In their study, the gallate ester moiety was found to be important for inhibition. Besides these effects, EGCG has the ability to reduce viral production in chronically infected monocytoid cells [143]. The inhibitory effect was increased by approximately 25%, when EGCG was modified with lyposomes.

Tea catechins are also effective against herpesviruses. EGCG has been shown to block EBV lytic cycle by inhibiting expression of viral genes including Rta, Zta and EA-D [13]. Further studies indicated that one of the mechanisms by which EGCG may inhibit EBV lytic cycle involves the suppression of MEK/ERK1/2 and PI3-K/Akt signaling pathways, which are involved in the EBV lytic cycle cascade [78]. Isaacs et al. found that EGCG can inactivate HSV virions by binding to the envelope glycoproteins gB and gD, which are essential for HSV infectivity [54]. The EGCG digallate dimers theasinensin A, P2, and theaflavin-3,3’-digallate inactivated HSV-1 and HSV-2 more effectively than did monomeric EGCG [55]. These dimers are stable at vaginal pH, indicating their potential to be antiviral agents against HSV infections.

The inhibitory effect of green tea extracts against HBV has been reported [140]. In HepG2.117 cells, EGCG inhibited HBV replication through impairing HBV replicative intermediates of DNA synthesis, thereby reducing the production of HBV covalently closed circular DNA [48]. In contrast, Huang et al. found that EGCG decreased HBV entry into immortalized human primary hepatocytes by more than 80% but had no effect on HBV genome replication [50]. Furthermore, EGCG is able to enhance lysosomal acidification, which is an unfavorable condition for HBV replication [155].

Besides these viruses, EGCG has been found to exert antiviral activity against HCV by preventing the attachment of the virus to the cell surface and suppressing RNA replication steps [8, 15]. A recent study also showed inhibitory activity of EGCG against another flavivirus, Zika virus (ZIKV): in this study, foci forming unit reduction assays were performed to evaluate the antiviral activity of EGCG on ZIKV at different stages of virus replication. Foci observed showed more than 90% inhibition when the cells were treated with EGCG during virus entry [10]. Similarly, EGCG is able to block CHIKV attachment to target cells, but has no effect on other stages of infection [132].

Antiviral activity of other flavonoids

Naringenin, which belongs to the flavanones class, has been shown to reduce the replication of a neurovirulent strain of Sindbis virus in vitro [102]. It also reduced Sindbis virus- and Semliki Forest virus-induced cytopathic effect in virus yield experiments [105]. Interestingly, naringin, the glycoside form of naringenin did not have anti-Sindbis virus activity, indicating that the rutinose moiety of this flavanone blocks its antiviral effect. Naringenin is also able to block the assembly of intracellular HCV particles and long-term treatment leads to 1.4 log reduction in HCV [39, 64]. The alphavirus CHIKV was effectively inhibited when infected Vero cells were treated with naringenin at the post-entry stage. In the same study, hesperetin, another flavanone which is found richly in citrus fruits, was found to exert most potent anti-CHIKV effect during the virus intracellular replication, with an IC50 of 8.5 µM [1]. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies by Oo et al. also revealed strong and stable interactions between hesperetin and CHIKV non-structural protein 2 (nsP2) as well as non-structural protein 3 (nsP3), suggesting that these proteins may be the target of hesperetin’s anti-CHIKV activity [101].

Genistein is an isoflavonoid found in a number of plants including soybeans and fava beans. As a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein reduced bovine herpesvirus type 1 and New World arenavirus Pichinde replication, by preventing the phosphorylation of viral proteins [2, 126]. Kinase inhibitor cocktails containing genistein displayed a broad-spectrum antiviral activity against arenaviruses and filoviruses [68]. Genistein was shown to inhibit HIV infection of resting CD4 T cells and macrophages through interference with HIV-mediated actin dynamics [42]. Furthermore, it may act against HIV ion channel since it has the ability to block the viral Vpu protein, which is believed to form a cation-permeable ion channel in infected cells [110]. Genistein also exerted its antiviral effects on the replication of HSV-1, HSV-2, and avian leucosis virus subgroup J, by inhibiting virus transcription [3, 106]. The antiviral activity of other flavonoids is presented in Table 2.

Future perspectives

In spite of the wide range of biological health benefits which flavonoids possess, in addition to their high availability in humans’ daily diets, there are challenges ahead for researchers before these natural compounds can be applied as therapeutic options in the clinical setting. Bioavailability, defined by the US Food and Drug Administration as “the rate and extent to which the active ingredient or active moiety is absorbed from a drug product and becomes available at the site of action”, has been the main stumbling block to further advances in the potential use of flavonoids in the medical community. Intake of metabolic derivatives of flavonoids from various food sources leads to relatively large differences in the final amount being successfully absorbed and utilized by humans [71]. Factors such as molecular sizes, glycosylation, esterification, lipophilicity, interactions with the enteric microorganisms, pKa, and other metabolic conjugations along the alimentary tract, affect the absorption and bioavailability of flavonoids in humans [49, 56, 69, 90, 93, 111, 133]. Hence, efforts in enhancing the bioavailability of flavonoids upon intake by humans are vitally necessary in order to develop these natural compounds into potential antiviral drugs. The following are a few examples of efforts being carried out to tackle this issue which can be used as platforms for further successes in the future.

In the past, researchers have looked into alternative methods to improve the compounds’ solubility or to switch the site of absorption in the gut, with the aim of enhancing their bioavailability. A structural modification to hesperetin-7-glucoside, which resulted in a change in site of absorption from the large to the small intestine, has successfully yielded a higher plasma level of hesperetin in healthy subjects [100]. Wang et al. [130] formulated a way to increase the oral bioavailability of flavonols extracted from sea buckthorn, by forming a phospholipid complex via solvent evaporation method. Relative to the parent compounds, oral bioavailability of the tested flavonols was 172% - 242% higher when the phospholipid complex was administered into rats [130]. Flavonoids loaded in engineered nanoparticles have also been tested for their bioavailability following oral consumption. Improved stability of catechin and EGCG in chitosan nanoparticles have been shown to result in a higher rate of intestinal absorption [29]. Poly (D, L-Lactide) (PLA) nanoparticles and polymeric micelles contributed to a more sustainable release of quercetin, which has poor bioavailability and undergoes substantial first-pass metabolism, as well as of the poorly absorbed apigenin [70, 124, 151]. Self-Microemulsifying Drug Delivery System (SMDDS) is another technology which has been used to overcome the problem of low bioavailability of hydrophobic molecules. Upon entering the lumen of the intestine, an oil-in-water microemulsion containing the drug will be formed. The microemulsion increases the intestinal absorption of the drug or compound by avoiding the dissolution process [60, 108]. Puerarin, an isoflavone isolated from the root of Pueraria lobata, exhibited 2.6-fold higher bioavailability when prepared using SMDDS [154].

However, it is worth noting that while the bioavailability of flavonoids can be increased via different methodologies, it is vital that their biological efficacies are not affected, but maintained or enhanced. For instance, phosphorylated icariin has been found to inhibit duck hepatitis virus A more effectively than the parent compound [138]. Isorhamnetin is a methylated flavonol derived from the structure of quercetin. Dayem et al. investigated the antiviral potency of isorhamnetin against influenza A H1N1 virus and discovered that the methyl group on the B ring enhances its antiviral activity compared with the other tested flavonoids [25]. The efficacy of isorhamnetin against influenza virus was also shown when in vivo and in ovo models were tested [25]. Improvement in bioavailability will definitely enhance the efficacy of different biological effects of all classes of flavonoids. Hence, in addition to discovering the hidden potentials of flavonoids, scientists should also aim to identify ways to increase the amount of flavonoids available for the health benefits of human beings.

Conclusion

Natural compounds have been the center of attention among researchers working in various fields, including those related with antiviral drug development, due to their high availability and low side effects. The phytochemicals flavonoids, which are abundantly found in our daily diets of fruits and vegetables, have been actively studied as potential therapeutic options against viruses of different taxa in the past decade. Numerous positive findings have been reported on the in vitro efficacy of flavonoids, but less promising results have been obtained for most compounds in in vivo studies. Multiple factors contributed to this scenario, and in vivo studies must be prioritized by researchers. It is well-known that flavonoids possess enormous potential to be included in the daily prescriptions by physicians treating illnesses ranging from infectious and oncogenic to inflammatory and chronic degenerative diseases. However, it is time for researchers worldwide to take the initiative in making these compounds a success not only in the in vitro stage of research, but also in animal models, as well as in subsequent clinical studies. Biochemistry and mechanistic studies on the flavonoids’ inhibitory activities can improve our understanding of how these natural compounds work and, on the other hand, identify the stumbling block that is hindering further improvements in flavonoids antiviral research.

References

Ahmadi A, Hassandarvish P, Lani R, Yadollahi P, Jokar A, Bakar SA, Zandi K (2016) Inhibition of chikungunya virus replication by hesperetin and naringenin. RSC Adv 6:69421–69430. doi:10.1039/C6RA16640G

Akula SM, Hurley DJ, Wixon RL, Wang C, Chase CC (2002) Effect of genistein on replication of bovine herpesvirus type 1. Am J Vet Res 63(8):1124–1128

Argenta DF, Silva IT, Bassani VL, Koester LS, Teixeira HF, Simões CM (2015) Antiherpes evaluation of soybean isoflavonoids. Arch Virol 160(9):2335–2342. doi:10.1007/s00705-015-2514-z

Bachmetov L, Gal-Tanamy M, Shapira A, Vorobeychik M, Giterman-Galam T, Sathiyamoorthy P, Golan-Goldhirsh A, Benhar I, Tur-Kaspa R, Zemel R (2012) Suppression of hepatitis C virus by the flavonoid quercetin is mediated by inhibition of NS3 protease activity. J Viral Hepat 19(2):e81–e88. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01507.x

Behbahani M, Sayedipour S, Pourazar A, Shanehsazzadeh M (2014) In vitro anti-HIV-1 activities of kaempferol and kaempferol-7-O-glucoside isolated from Securigera securidaca. Res Pharm Sci 9(6):463–469

Bowles D, Isayenkova J, Lim EK, Poppenberger B (2005) Glycosyltransferases: managers of small molecules. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8(3):254–263. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2005.03.007

Bullock AN, Debreczeni JÉ, Fedorov OY, Nelson A, Marsden BD, Knapp S (2005) Structural basis of inhibitor specificity of the human protooncogene proviral insertion site in moloney murine leukemia virus (PIM-1) kinase. J Med Chem 48:7604–7614. doi:10.1021/jm0504858

Calland N, Albecka A, Belouzard S, Wychowski C, Duverlie G, Descamps V, Hober D, Dubuisson J, Rouillé Y, Séron K (2012) (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate is a new inhibitor of hepatitis C virus entry. Hepatology 55(3):720–729. doi:10.1002/hep.24803

Carletti G, Nervo G, Cattivelli L (2014) Flavonoids and Melanins: a common strategy across two kingdoms. Int J Biol Sci 10(10):1159–1170

Carneiro BM, Batista MN, Braga ACS, Nogueira ML, Rahal P (2016) The green tea molecule EGCG inhibits Zika virus entry. Virology 496:215–218. doi:10.7150/ijbs.9672

Carvalho OV, Botelho CV, Ferreira CG, Ferreira HC, Santos MR, Diaz MA, Oliveira TT, Soares-Martins JA, Almeida MR, Silva A Jr (2013) In vitro inhibition of canine distemper virus by flavonoids and phenolic acids: implications of structural differences for antiviral design. Res Vet Sci 95(2):717–724. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.04.013

Castrillo M, Córdova T, Cabrera G, Rodríguez-Ortega M (2015) Effect of naringenin, hesperetin and their glycosides forms on the replication of the 17D strain of yellow fever virus. Avan Biomed 4:69–78

Chang LK, Wei TT, Chiu YF, Tung CP, Chuang JY, Hung SK, Li C, Liu ST (2003) Inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle by (−)-epigallocatechin gallate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 301(4):1062–1068

Chantrill BH, Coulthard CE, Dickinson L, Inkley GW, Morris W, Pyle AH (1952) The action of plant extracts on a bacteriophage of Pseudomonas pyocyanea and on influenza A virus. J Gen Microbiol 6:74–84. doi:10.1099/00221287-6-1-2-74

Chen C, Qiu H, Gong J, Liu Q, Xiao H, Chen XW, Sun BL, Yang RG (2012) (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits the replication cycle of hepatitis C virus. Arch Virol 157(7):1301–1312. doi:10.1007/s00705-012-1304-0

Chiang LC, Chiang W, Liu MC, Lin CC (2003) In vitro antiviral activities of Caesalpinia pulcherrima and its related flavonoids. J Antimicrob Chemother 52(2):194–198. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg291

Chiang LC, Ng LT, Cheng PW, Chiang W, Lin CC (2005) Antiviral activities of extracts and selected pure constituents of Ocimum basilicum. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 32:811–816. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04270.x

Cho WK, Weeratunga P, Lee BH, Park JS, Kim CJ, Ma JY, Lee JS (2015) Epimedium koreanum Nakai displays broad spectrum of antiviral activity in vitro and in vivo by inducing cellular antiviral state. Viruses 7(1):352–377. doi:10.3390/v7010352

Chu M, Xu L, Zhang MB, Chu ZY, Wang YD (2015) Role of Baicalin in anti-influenza virus A as a potent inducer of IFN-gamma. Biomed Res Int 2015:263630. doi:10.1155/2015/263630

Chu SC, Hsieh YS, Lin JY (1992) Inhibitory effects of flavonoids on Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase activity. J Nat Prod 55(2):179–183

Chung ST, Chien PY, Huang WH, Yao CW, Lee AR (2014) Synthesis and anti-influenza activities of novel baicalein analogs. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 62(5):415–421

Colpitts CC, Schang LM (2014) A small molecule inhibits virion attachment to heparan sulfate- or sialic acid-containing glycans. J Virol 88(14):7806–7817. doi:10.1128/JVI.00896-14

Cotin S, Calliste CA, Mazeron MC, Hantz S, Duroux JL, Rawlinson WD, Ploy MC, Alain S (2012) Eight flavonoids and their potential as inhibitors of human cytomegalovirus replication. Antiviral Res 96(2):181–186. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.09.010

Croft KD (1998) The chemistry and biological effects of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Ann N Y Acad Sci 854:435–442

Dayem AA, Choi HY, Kim YB, Cho S-G (2015) Antiviral effect of methylated flavonol isorhamnetin against influenza. PLoS One 10:e0121610. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121610

Ding Y, Dou J, Teng Z, Yu J, Wang T, Lu N, Wang H, Zhou C (2014) Antiviral activity of baicalin against influenza A (H1N1/H3N2) virus in cell culture and in mice and its inhibition of neuraminidase. Arch Virol 159(12):3269–3278. doi:10.1007/s00705-014-2192-2

dos Santos AE, Kuster RM, Yamamoto KA, Salles TS, Campos R, de Meneses MD, Soares MR, Ferreira D (2014) Quercetin and quercetin 3-O-glycosides from Bauhinia longifolia (Bong.) Steud. show anti-Mayaro virus activity. Parasit Vectors 7:130. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-7-130

Dou J, Chen L, Xu G, Zhang L, Zhou H, Wang H, Su Z, Ke M, Guo Q, Zhou C (2011) Effects of baicalein on Sendai virus in vivo are linked to serum baicalin and its inhibition of hemagglutinin-neuraminidase. Arch Virol 156(5):793–801. doi:10.1007/s00705-011-0917-z

Dube A, Nicolazzo JA, Larson I (2010) Chitosan nanoparticles enhance the intestinal absorption of the green tea catechins (+)-catechin and (−)-epigallocatechin gallate. Eur J Pharm Sci 41:219–225. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2010.06.010

Ekor M (2014) The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol 4:177. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00177

Evers DL, Chao CF, Wang X, Zhang Z, Huong SM, Huang ES (2005) Human cytomegalovirus-inhibitory flavonoids: studies on antiviral activity and mechanism of action. Antiviral Res 68(3):124–134. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.08.002

Falcone Ferreyra ML, Rius SP, Casati P (2012) Flavonoids: biosynthesis, biological functions, and biotechnological applications. Front Plant Sci 3:222. doi:10.3389/fpls.2012.00222

Fan W, Qian S, Qian P, Li X (2016) Antiviral activity of luteolin against Japanese encephalitis virus. Virus Res 220:112–116. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2016.04.021

Fatima K, Mathew S, Suhail M, Ali A, Damanhouri G, Azhar E, Qadri I (2014) Docking studies of Pakistani HCV NS3 helicase: a possible antiviral drug target. PLoS One 9(9):e106339. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106339

Ferrer JL, Austin MB, Stewart C Jr, Noel JP (2008) Structure and function of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids. Plant Physiol Biochem 46(3):356–370. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.12.009

French CJ, Towers GN (1992) Inhibition of infectivity of potato virus X by flavonoids. Phytochemistry 31:3017–3020

Ganesan S, Faris AN, Comstock AT, Wang Q, Nanua S, Hershenson MB, Sajjan US (2012) Quercetin inhibits rhinovirus replication in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res 94(3):258–271. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.03.005

Gao J, Xiao S, Liu X, Wang L, Ji Q, Mo D, Chen Y (2014) Inhibition of HSP70 reduces porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication in vitro. BMC Microbiol 14:64. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-14-64

Goldwasser J, Cohen PY, Lin W, Kitsberg D, Balaguer P, Polyak SJ, Chung RT, Yarmush ML, Nahmias Y (2011) Naringenin inhibits the assembly and long-term production of infectious hepatitis C virus particles through a PPAR-mediated mechanism. J Hepatol 55(5):963–971. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.011

Gorlach S, Fichna J, Lewandowska U (2015) Polyphenols as mitochondria-targeted anticancer drugs. Cancer Lett 366(2):141–149. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.004

Gravina HD, Tafuri NF, Silva Júnior A, Fietto JL, Oliveira TT, Diaz MA, Almeida MR (2011) In vitro assessment of the antiviral potential of trans-cinnamic acid, quercetin and morin against equid herpesvirus 1. Res Vet Sci 91(3):e158–e162. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.11.010

Guo J, Xu X, Rasheed TK, Yoder A, Yu D, Liang H, Yi F, Hawley T, Jin T, Ling B, Wu Y (2013) Genistein interferes with SDF-1- and HIV-mediated actin dynamics and inhibits HIV infection of resting CD4 T cells. Retrovirology 10:62. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-10-62

Guo Q, Zhao L, You Q, Yang Y, Gu H, Song G, Lu N, Xin J (2007) Anti-hepatitis B virus activity of wogonin in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res 74:16–24. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.01.002

Güttner J, Veckenstedt A, Heinecke H, Pusztai R (1982) Effect of quercetin on the course of mengo virus infection in immunodeficient and normal mice. A histologic study. Acta Virol 26(3):148–155

Ha SY, Youn H, Song CS, Kang SC, Bae JJ, Kim HT, Lee KM, Eom TH, Kim IS, Kwak JH (2014) Antiviral effect of flavonol glycosides isolated from the leaf of Zanthoxylum piperitum on influenza virus. J Microbiol 52(4):340–344. doi:10.1007/s12275-014-4073-5

Hakobyan A, Arabyan E, Avetisyan A, Abroyan L, Hakobyan L, Zakaryan H (2016) Apigenin inhibits African swine fever virus infection in vitro. Arch Virol 161(12):3445–3453. doi:10.1007/s00705-016-3061-y

Hassandarvish P, Rothan HA, Rezaei S, Yusof R, Abubakar S, Zandi K (2016) In silico study on baicalein and baicalin as inhibitors of dengue virus replication. RSC Advances 6:31235–31247. doi:10.1039/C6RA00817H

He W, Li LX, Liao QJ, Liu CL, Chen XL (2011) Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits HBV DNA synthesis in a viral replication—inducible cell line. World J Gastroenterol 17(11):1507–1514. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i11.1507

Hollman PC, Bijsman MN, van Gameren Y, Cnossen EP, de Vries JH, Katan MB (1999) The sugar moiety is a major determinant of the absorption of dietary flavonoid glycosides in man. Free Radic Res 31:569–573

Huang HC, Tao MH, Hung TM, Chen JC, Lin ZJ, Huang C (2014) (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits entry of hepatitis B virus into hepatocytes. Antiviral Res 111:100–111. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.09.009

Hung PY, Ho BC, Lee SY, Chang SY, Kao CL, Lee SS, Lee CN (2015) Houttuynia cordata targets the beginning stage of herpes simplex virus infection. PLoS One 10(2):e0115475. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115475

Imanishi N, Tuji Y, Katada Y, Maruhashi M, Konosu S, Mantani N, Terasawa K, Ochiai H (2002) Additional inhibitory effect of tea extract on the growth of influenza A and B viruses in MDCK cells. Microbiol Immunol 46(7):491–494

Iranshahi M, Rezaee R, Parhiz H, Roohbakhsh A, Soltani F (2015) Protective effects of flavonoids against microbes and toxins: the cases of hesperidin and hesperetin. Life Sci 137:125–132. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2015.07.014

Isaacs CE, Wen GY, Xu W, Jia JH, Rohan L, Corbo C, Di Maggio V, Jenkins EC Jr, Hillier S (2008) Epigallocatechin gallate inactivates clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52(3):962–970. doi:10.1128/AAC.00825-07

Isaacs CE, Xu W, Merz G, Hillier S, Rohan L, Wen GY (2011) Digallate dimers of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate inactivate herpes simplex virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55(12):5646–5653. doi:10.1128/AAC.05531-11

Jaganath IB, Jaganath IB, Mullen W, Edwards CA, Crozier A (2006) The relative contribution of the small and large intestine to the absorption and metabolism of rutin in man. Free Rad Res 40:1035–1046

Jeong HJ, Ryu YB, Park S-J, Kim JH, Kwon H-J, Kim JH, Park KH, Rho M-C, Lee WS (2009) Neuraminidase inhibitory activities of flavonols isolated from Rhodiola rosea roots and their in vitro anti-influenza viral activities. Bioorg Med Chem 17:6816–6823. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.036

Ji S, Li R, Wang Q, Miao WJ, Li ZW, Si LL, Qiao X, Yu SW, Zhou DM, Ye M (2015) Anti-H1N1 virus, cytotoxic and Nrf2 activation activities of chemical constituents from Scutellaria baicalensis. J Ethnopharmacol 176:475–484. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.018

Johari J, Kianmehr A, Mustafa MR, Abubakar S, Zandi K (2012) Antiviral activity of baicalein and quercetin against the Japanese encephalitis virus. Int J Mol Sci 13(12):16785–16795. doi:10.3390/ijms131216785

Kang BK, Lee JS, Chon SK, Jeong SY, Yuk SH, Khang G, Lee HB, Cho SH (2004) Development of self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems (SMEDDS) for oral bioavailability enhancement of simvastatin in beagle dogs. Int J Pharm 274:65–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.12.028

Kaul TN, Middleton E, Ogra PL (1985) Antiviral effect of flavonoids on human viruses. J Med Virol 15:71–79

Kawai K, Tsuno NH, Kitayama J, Okaji Y, Yazawa K, Asakage M, Hori N, Watanabe T, Takahashi K, Nagawa H (2003) Epigallocatechin gallate, the main component of tea polyphenol, binds to CD4 and interferes with gp120 binding. J Allergy Clin Immunol 112(5):951–957. doi:10.1016/S0091

Keum Y-S, Jeong Y-J (2012) Development of chemical inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus: viral helicase as a potential target. Biochem Pharm 84:1351–1358. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2012.08.012

Khachatoorian R, Arumugaswami V, Raychaudhuri S, Yeh GK, Maloney EM, Wang J, Dasgupta A, French SW (2012) Divergent antiviral effects of bioflavonoids on the hepatitis C virus life cycle. Virology 433(2):346–355. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2012.08.029

Khan N, Syed DN, Ahmad N, Mukhtar H (2013) Fisetin: a dietary antioxidant for health promotion. Antioxid Redox Signal 19(2):151–162. doi:10.1089/ars.2012.4901

Kim M, Kim SY, Lee HW, Shin JS, Kim P, Jung YS, Jeong HS, Hyun JK, Lee CK (2013) Inhibition of influenza virus internalization by (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Antiviral Res 100(2):460–472. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.08.002

Knipping K, Garssen J, van’t Land B (2012) An evaluation of the inhibitory effects against rotavirus infection of edible plant extracts. Virol J 9:137. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-9-137

Kolokoltsov AA, Adhikary S, Garver J, Johnson L, Davey RA, Vela EM (2012) Inhibition of Lassa virus and Ebola virus infection in host cells treated with the kinase inhibitors genistein and tyrphostin. Arch Virol 157(1):121–127. doi:10.1007/s00705-011-1115-8

Kumar S, Pandey AK (2013) Chemistry and biological activities of flavonoids: an overview. Sci World J 2013:162750. doi:10.1155/2013/162750

Kumari A, Yadav SK, Pakade YB, Singh B, Yadav SC (2010) Development of biodegradable nanoparticles for delivery of quercetin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 80:184–192. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.06.002

Landete J (2012) Updated knowledge about polyphenols: functions, bioavailability, metabolism, and health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 52:936–948. doi:10.1080/10408398.2010.513779

Lani R, Hassandarvish P, Chiam CW, Moghaddam E, Chu JJH, Rausalu K, Merits A, Higgs S, Vanlandingham D, Bakar SA (2015) Antiviral activity of silymarin against chikungunya virus. Sci Rep 5:11421. doi:10.1038/srep11421

Lani R, Hassandarvish P, Shu MH, Phoon WH, Chu JJ, Higgs S, Vanlandingham D, Abu Bakar S, Zandi K (2016) Antiviral activity of selected flavonoids against Chikungunya virus. Antiviral Res 133:50–61. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.07.009

Lee HS, K-s Park, Lee C, Lee B, Kim D-E, Chong Y (2010) 7-O-Arylmethylgalangin as a novel scaffold for anti-HCV agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 20:5709–5712. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.012

Li BQ, Fu T, Dongyan Y, Mikovits JA, Ruscetti FW, Wang JM (2000) Flavonoid baicalin inhibits HIV-1 infection at the level of viral entry. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 276:534–538. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3485

Lin YJ, Chang YC, Hsiao NW, Hsieh JL, Wang CY, Kung SH, Tsai FJ, Lan YC, Lin CW (2012) Fisetin and rutin as 3C protease inhibitors of enterovirus A71. J Virol Methods 182(1–2):93–98. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.03.020

Liu A-L, Wang H-D, Lee SM, Wang Y-T, Du G-H (2008) Structure-activity relationship of flavonoids as influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitors and their in vitro anti-viral activities. Bioorg Med Chem 16:7141–7147. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.06.049

Liu S, Li H, Chen L, Yang L, Li L, Tao Y, Li W, Li Z, Liu H, Tang M, Bode AM, Dong Z, Cao Y (2013) (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus spontaneous lytic infection involves ERK1/2 and PI3-K/Akt signaling in EBV-positive cells. Carcinogenesis 34(3):627–637. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgs364

Liu Z, Zhao J, Li W, Shen L, Huang S, Tang J, Duan J, Fang F, Huang Y, Chang H, Chen Z, Zhang R (2016) Computational screen and experimental validation of anti-influenza effects of quercetin and chlorogenic acid from traditional Chinese medicine. Sci Rep 6:19095. doi:10.1038/srep19095

Liu Z, Zhao J, Li W, Wang X, Xu J, Xie J, Tao K, Shen L, Zhang R (2015) Molecular docking of potential inhibitors for influenza H7N9. Comput Math Methods Med 2015:480764. doi:10.1155/2015/480764

Lu N, Khachatoorian R, French SW (2012) Quercetin: bioflavonoids as part of interferon-free hepatitis C therapy? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 10(6):619–621. doi:10.1586/eri.12.52

Lv X, Qiu M, Chen D, Zheng N, Jin Y, Wu Z (2014) Apigenin inhibits enterovirus 71 replication through suppressing viral IRES activity and modulating cellular JNK pathway. Antiviral Res 109:30–41. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.06.004

Lyu SY, Rhim JY, Park WB (2005) Antiherpetic activities of flavonoids against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) in vitro. Arch Pharm Res 28(11):1293–1301

Mandal SM, Chakraborty D, Dey S (2010) Phenolic acids act as signaling molecules in plant-microbe symbioses. Plant Signal Behav 5(4):359–368

Manvar D, Mishra M, Kumar S, Pandey VN (2012) Identification and evaluation of antihepatitis C virus phytochemicals from Eclipta alba. J Ethnopharmacol 144(3):545–554. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2012.09.036

Mathew S, Fatima K, Fatmi MQ, Archunan G, Ilyas M, Begum N, Azhar E, Damanhouri G, Qadri I (2015) Computational docking study of p7 Ion channel from HCV genotype 3 and genotype 4 and its interaction with natural compounds. PLoS One 10(6):e0126510. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126510

Mehla R, Bivalkar-Mehla S, Chauhan A (2011) A flavonoid, luteolin, cripples HIV-1 by abrogation of tat function. PLoS One 6(11):e27915. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027915

Middleton E Jr, Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC (2000) The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev 52(4):673–751

Mitrocotsa D, Mitaku S, Axarlis S, Harvala C, Malamas M (2000) Evaluation of the antiviral activity of kaempferol and its glycosides against human cytomegalovirus. Planta Med 66(4):377–379. doi:10.1055/s-2000-8550

Moco S, Fo-PJ Martin, Rezzi S (2012) Metabolomics view on gut microbiome modulation by polyphenol-rich foods. J Proteome Res 11:4781–4790. doi:10.1021/pr300581s

Moghaddam E, Teoh BT, Sam SS, Lani R, Hassandarvish P, Chik Z, Yueh A, Abubakar S, Zandi K (2014) Baicalin, a metabolite of baicalein with antiviral activity against dengue virus. Sci Rep 4:5452. doi:10.1038/srep05452

Mucsi I, Gyulai Z, Béládi I (1992) Combined effects of flavonoids and acyclovir against herpesviruses in cell cultures. Acta Microbiol Hung 39(2):137–147

Mullen W, Edwards CA, Crozier A (2006) Absorption, excretion and metabolite profiling of methyl-, glucuronyl-, glucosyl-and sulpho-conjugates of quercetin in human plasma and urine after ingestion of onions. Br J Nutr 96:107–116

Murali KS, Sivasubramanian S, Vincent S, Murugan SB, Giridaran B, Dinesh S, Gunasekaran P, Krishnasamy K, Sathishkumar R (2015) Anti-chikungunya activity of luteolin and apigenin rich fraction from Cynodon dactylon. Asian Pac J Trop Med 8(5):352–358. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60343-6

Nabavi SF, Braidy N, Habtemariam S, Orhan IE, Daglia M, Manayi A, Gortzi O, Nabavi SM (2015) Neuroprotective effects of chrysin: from chemistry to medicine. Neurochem Int 90:224–231. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2015.09.006

Nakane H, Ono K (1989) Differential inhibition of HIV-reverse transcriptase and various DNA and RNA polymerases by somecatechin derivatives. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 21:115–116

Nakane H, Ono K (1990) Differential inhibitory effects of some catechin derivatives on the activities of human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and cellular deoxyribonucleic and ribonucleic acid polymerases. Biochemistry 29(11):2841–2845

Nakayama M, Suzuki K, Toda M, Okubo S, Hara Y, Shimamura T (1993) Inhibition of the infectivity of influenza virus by tea polyphenols. Antiviral Res 21(4):289–299

Nayak MK, Agrawal AS, Bose S, Naskar S, Bhowmick R, Chakrabarti S, Sarkar S, Chawla-Sarkar M (2014) Antiviral activity of baicalin against influenza virus H1N1-pdm09 is due to modulation of NS1-mediated cellular innate immune responses. J Antimicrob Chemother 69(5):1298–1310. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt534

Nielsen ILF, Chee WS, Poulsen L, Offord-Cavin E, Rasmussen SE, Frederiksen H, Enslen M, Barron D, Horcajada M-N, Williamson G (2006) Bioavailability is improved by enzymatic modification of the citrus flavonoid hesperidin in humans: a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. J Nutr 136:404–408

Oo A, Hassandarvish P, Chin SP, Lee VS, Bakar SA, Zandi K (2016) In silico study on anti-Chikungunya virus activity of hesperetin. PeerJ 4:e2602. doi:10.7717/peerj.2602

Paredes A, Alzuru M, Mendez J, Rodríguez-Ortega M (2003) Anti-Sindbis activity of flavanones hesperetin and naringenin. Biol Pharm Bull 26(1):108–109

Pasetto S, Pardi V, Murata RM (2014) Anti-HIV-1 activity of flavonoid myricetin on HIV-1 infection in a dual-chamber in vitro model. PLoS One 9:e115323. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115323

Patel J, Choubisa B, Dholakiya B (2011) Plant derived compounds having activity against P388 and L1210 leukemia cells. J Chem Sci 1:1–16

Pohjala L, Utt A, Varjak M, Lulla A, Merits A, Ahola T, Tammela P (2011) Inhibitors of alphavirus entry and replication identified with a stable Chikungunya replicon cell line and virus-based assays. PLoS One 6(12):e28923. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028923

Qian K, Gao AJ, Zhu MY, Shao HX, Jin WJ, Ye JQ, Qin AJ (2014) Genistein inhibits the replication of avian leucosis virus subgroup J in DF-1 cells. Virus Res 192:114–120. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2014.08.016

Qian S, Fan W, Qian P, Zhang D, Wei Y, Chen H, Li X (2015) Apigenin restricts FMDV infection and inhibits viral IRES driven translational activity. Viruses 7(4):1613–1626. doi:10.3390/v7041613

Rogerio AP, Dora CL, Andrade EL, Chaves JS, Silva LF, Lemos-Senna E, Calixto JB (2010) Anti-inflammatory effect of quercetin-loaded microemulsion in the airways allergic inflammatory model in mice. Pharmacol Res 61:288–297. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2009.10.005

Samuelsson G (1999) Drugs of natural origin. Swedish Pharmaceutical Press, Stockholm

Sauter D, Schwarz S, Wang K, Zhang R, Sun B, Schwarz W (2014) Genistein as antiviral drug against HIV ion channel. Planta Med 80(8–9):682–687. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1368583

Scalbert A, Morand C, Manach C, Rémésy C (2002) Absorption and metabolism of polyphenols in the gut and impact on health. Biomed Pharmacother 56:276–282

Schwarz S, Sauter D, Wang K, Zhang R, Sun B, Karioti A, Bilia AR, Efferth T, Schwarz W (2014) Kaempferol derivatives as antiviral drugs against the 3a channel protein of coronavirus. Planta Med 80(2–3):177–182. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1360277

Seo DJ, Jeon SB, Oh H, Lee B-H, Lee S-Y, Oh SH, Jung JY, Choi C (2016) Comparison of the antiviral activity of flavonoids against murine norovirus and feline calicivirus. Food Control 60:25–30. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.07.023

Seyedi SS, Shukri M, Hassandarvish P, Oo A, Muthu SE, Abubakar S, Zandi K (2016) Computational approach towards exploring potential anti-Chikungunya activity of selected flavonoids. Sci Rep 6:24027. doi:10.1038/srep24027

Shibata C, Ohno M, Otsuka M, Kishikawa T, Goto K, Muroyama R, Kato N, Yoshikawa T, Takata A, Koike K (2014) The flavonoid apigenin inhibits hepatitis C virus replication by decreasing mature microRNA122 levels. Virology 462–463:42–48. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2014.05.024

Sithisarn P, Michaelis M, Schubert-Zsilavecz M, Cinatl J Jr (2013) Differential antiviral and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of the flavonoids biochanin A and baicaleinin H5N1 influenza A virus-infected cells. Antiviral Res 97(1):41–48. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.004

Song J-H, Kwon B-E, Jang H, Kang H, Cho S, Park K, Ko H-J, Kim H (2015) Antiviral activity of chrysin derivatives against Coxsackievirus B3 in vitro and in vivo. Biomol Ther 23:465. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2015.095

Song JH, Shim JK, Choi HJ (2011) Quercetin 7-rhamnoside reduces porcine epidemic diarrhea virus replication via independent pathway of viral induced reactive oxygen species. Virol J 8:460. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-460

Song JH, Choi HJ (2011) Silymarin efficacy against influenza A virus replication. Phytomedicine 18(10):832–835. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2011.01.026

Song JM, Lee KH, Seong BL (2005) Antiviral effect of catechins in green tea on influenza virus. Antiviral Res 68(2):66–74. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.06.010

Song JM, Park KD, Lee KH, Byun YH, Park JH, Kim SH, Kim JH, Seong BL (2007) Biological evaluation of anti-influenza viral activity of semi-synthetic catechin derivatives. Antiviral Res 76(2):178–185. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.07.001

Song JM, Seong BL (2007) Tea catechins as a potential alternative anti-infectious agent. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 5(3):497–506. doi:10.1586/14787210.5.3.497

Tao J, Hu Q, Yang J, Li R, Li X, Lu C, Chen C, Wang L, Shattock R, Ben K (2007) In vitro anti-HIV and -HSV activity and safety of sodium rutin sulfate as a microbicide candidate. Antiviral Res 75(3):227–233. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.03.008

Tillekeratne LM, Sherette A, Grossman P, Hupe L, Hupe D, Hudson RA (2001) Simplified catechin-gallate inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 11(20):2763–2767

Veckenstedt A, Güttner J, Béládi I (1987) Synergistic action of quercetin and murine alpha/beta interferon in the treatment of Mengo virus infection in mice. Antiviral Res 7(3):169–178

Vela EM, Bowick GC, Herzog NK, Aronson JF (2008) Genistein treatment of cells inhibits arenavirus infection. Antiviral Res 77(2):153–156. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.09.005

Visintini Jaime MF, Redko F, Muschietti LV, Campos RH, Martino VS, Cavallaro LV (2013) In vitro antiviral activity of plant extracts from Asteraceae medicinal plants. Virol J 10:245. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-10-245

Wagoner J, Negash A, Kane OJ, Martinez LE, Nahmias Y, Bourne N, Owen DM, Grove J, Brimacombe C, McKeating JA (2010) Multiple effects of silymarin on the hepatitis C virus lifecycle. Hepatology 51:1912–1921. doi:10.1002/hep.23587

Wang C, Wang P, Chen X, Wang W, Jin Y (2015) Saururus chinensis (Lour.) Baill blocks enterovirus 71 infection by hijacking MEK1-ERK signaling pathway. Antiviral Res 119:47–56. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.04.009

Wang H, Cui Y, Fu Q, Deng B, Li G, Yang J, Wu T, Xie Y (2015) A phospholipid complex to improve the oral bioavailability of flavonoids. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 41:1693–1703. doi:10.3109/03639045.2014.991402

Wang J, Zhang T, Du J, Cui S, Yang F, Jin Q (2014) Anti-enterovirus 71 effects of chrysin and its phosphate ester. PLoS One 9:e89668. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089668

Weber C, Sliva K, von Rhein C, Kümmerer BM, Schnierle BS (2015) The green tea catechin, epigallocatechin gallate inhibits Chikungunya virus infection. Antiviral Res 113:1–3. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.11.001

Williamson G, Clifford MN (2010) Colonic metabolites of berry polyphenols: the missing link to biological activity? Br J Nutr 104:S48–S66. doi:10.1017/S0007114510003946

Williamson MP, McCormick TG, Nance CL, Shearer WT (2006) Epigallocatechin gallate, the main polyphenol in green tea, binds to the T-cell receptor, CD4: Potential for HIV-1 therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 118(6):1369–1374. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.016

Wu H, Myszka DG, Tendian SW, Brouillette CG, Sweet RW, Chaiken IM, Hendrickson WA (1996) Kinetic and structural analysis of mutant CD4 receptors that are defective in HIV gp120binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93(26):15030–15035

Wu W, Li R, Li X, He J, Jiang S, Liu S, Yang J (2015) Quercetin as an antiviral agent inhibits Influenza A virus (IAV) Entry. Viruses. doi:10.3390/v8010006 (pii: E6)

Xia EQ, Deng GF, Guo YJ, Li H (2010) Biological activities of polyphenols from grapes. Int J Mol Sci 11(2):622–646. doi:10.3390/ijms11020622

Xiong W, Ma X, Wu Y, Chen Y, Zeng L, Liu J, Sun W, Wang D, Hu Y (2015) Determine the structure of phosphorylated modification of icariin and its antiviral activity against duck hepatitis virus A. BMC Vet Res 11:1. doi:10.1186/s12917-015-0459-9

Xu G, Dou J, Zhang L, Guo Q, Zhou C (2010) Inhibitory effects of baicalein on the influenza virus in vivo is determined by baicalin in the serum. Biol Pharm Bull 33(2):238–243

Xu J, Wang J, Deng F, Hu Z, Wang H (2008) Green tea extract and its major component epigallocatechin gallate inhibits hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antiviral Res 78(3):242–249. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.11.011

Xu J-J, Liu Z, Tang W, Wang G-C, Chung HY, Liu Q-Y, Zhuang L, Li M-M, Li Y-L (2015) Tangeretin from citrus reticulate inhibits respiratory syncytial virus replication and associated inflammation in vivo. J Agric Food Chem 63:9520–9527. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03482

Xu L, Su W, Jin J, Chen J, Li X, Zhang X, Sun M, Sun S, Fan P, An D, Zhang H, Zhang X, Kong W, Ma T, Jiang C (2014) Identification of luteolin as enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 inhibitors through reporter viruses and cell viability-based screening. Viruses 6(7):2778–2795. doi:10.3390/v6072778

Yamaguchi K, Honda M, Ikigai H, Hara Y, Shimamura T (2002) Inhibitory effects of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate on the life cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Antiviral Res 53(1):19–34

Yang L, Lin J, Zhou B, Liu Y, Zhu B (2016) Activity of compounds from Taxillus sutchuenensis as inhibitors of HCV NS3 serine protease. Nat Prod Res 13:1–5. doi:10.1080/14786419.2016.1190719

Yarmolinsky L, Huleihel M, Zaccai M, Ben-Shabat S (2012) Potent antiviral flavone glycosides from Ficus benjamina leaves. Fitoterapia 83(2):362–367. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2011.11.014

Yi L, Li Z, Yuan K, Qu X, Chen J, Wang G, Zhang H, Luo H, Zhu L, Jiang P, Chen L, Shen Y, Luo M, Zuo G, Hu J, Duan D, Nie Y, Shi X, Wang W, Han Y, Li T, Liu Y, Ding M, Deng H, Xu X (2004) Small molecules blocking the entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into host cells. J Virol 78(20):11334–11339. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.20.11334-11339.2004

Yu MS, Lee J, Lee JM, Kim Y, Chin YW, Jee JG, Keum YS, Jeong YJ (2012) Identification of myricetin and scutellarein as novel chemical inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus helicase, nsP13. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 22(12):4049–4054. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.081

Zandi K, Lim TH, Rahim NA, Shu MH, Teoh BT, Sam SS, Danlami MB, Tan KK, Abubakar S (2013) Extract of Scutellaria baicalensis inhibits dengue virus replication. BMC Complement Altern Med 13:91. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-13-91

Zandi K, Teoh BT, Sam SS, Wong PF, Mustafa MR, Abubakar S (2011) Antiviral activity of four types of bioflavonoid against dengue virus type-2. Virol J 8:560. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-560

Zandi K, Teoh BT, Sam SS, Wong PF, Mustafa MR, Abubakar S (2012) Novel antiviral activity of baicalein against dengue virus. BMC Complement Altern Med 12:214. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-12-214

Zhai Y, Guo S, Liu C, Yang C, Dou J, Li L, Zhai G (2013) Preparation and in vitro evaluation of apigenin-loaded polymeric micelles. Colloids Surf A 429:24–30. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.03.051

Zhang T, Wu Z, Du J, Hu Y, Liu L, Yang F, Jin Q (2012) Anti-Japanese-encephalitis-viral effects of kaempferol and daidzin and their RNA-binding characteristics. PLoS One 7:e30259. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030259

Zhang W, Qiao H, Lv Y, Wang J, Chen X, Hou Y, Tan R, Li E (2014) Apigenin inhibits enterovirus-71 infection by disrupting viral RNA association with trans-acting factors. PLoS One 9(10):e110429. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110429

Zhang Y, Wang R, Wu J, Shen Q (2012) Characterization and evaluation of self-microemulsifying sustained-release pellet formulation of puerarin for oral delivery. Int J Pharm 427:337–344. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.02.013

Zhong L, Hu J, Shu W, Gao B, Xiong S (2015) Epigallocatechin-3-gallate opposes HBV-induced incomplete autophagy by enhancing lysosomal acidification, which is unfavorable for HBV replication. Cell Death Dis 6:e1770. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.136

Zoratti L, Karppinen K, Luengo Escobar A, Häggman H, Jaakola L (2014) Light-controlled flavonoid biosynthesis in fruits. Front Plant Sci 5:534. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00534

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all reviewers whose detailed comments improved the review and apologize to those authors whose contribution to flavonoids antiviral research may have been inadvertently missed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

This study is supported by the RA MES State Committee of Science, in the frames of the research projects 15RF-081 and 16YR-1F064. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zakaryan, H., Arabyan, E., Oo, A. et al. Flavonoids: promising natural compounds against viral infections. Arch Virol 162, 2539–2551 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-017-3417-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-017-3417-y