Abstract

Infection with West Nile virus and dengue virus, two mosquito-borne flaviviruses, is enhanced by two calcium-dependent lectins: dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN), and its related molecule (DC-SIGNR). The present study examined the relationship between Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection and three lectins: DC-SIGN, DC-SIGNR, and liver sinusoidal endothelial cell lectin (LSECtin). Expression of DC-SIGNR resulted in robust JEV proliferation in a lymphoid cell line, Daudi cells, which was otherwise non-permissive to infection. DC-SIGN expression caused moderate JEV proliferation, with effects that varied according to the cells in which JEV was prepared. LSECtin expression had comparatively minor, but consistent, effects, in all cell types used in JEV preparation. While DC-SIGN/DC-SIGNR-mediated JEV infection was inhibited by yeast mannan, LSECtin-mediated infection was inhibited by N-acetylglucosamine β1-2 mannose. Although involvement of DC-SIGN/DC-SIGNR in infection seems to be a common characteristic, this is the first report on usage of LSECtin in mosquito-borne flavivirus infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is maintained by a transmission cycle between pigs/birds and mosquitoes. Incidental infection of humans and horses causes Japanese encephalitis (JE) [1]. The virus belongs to the genus Flavivirus of the family Flaviviridae. West Nile virus (WNV), dengue virus (DV), yellow fever virus and JEV are representatives of the mosquito-borne viruses in the genus [1].

Based on studies performed in rodent models [2, 3], the following pattern has been proposed for the propagation in the human body of Murray Valley encephalitis virus (MVEV) and St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), two other members of the genus Flavivirus: MVEV or SLEV is injected during a bite from an infected mosquito and first infects dendritic cells (DCs) in the skin; the infected DCs move to a draining lymph node, which is an initial replication site; from the draining lymph node, MVEV/SLEV enters into circulation via the efferent lymphatic system, which permits its spread to visceral organs and viremia. While it is known that MVEV and SLEV cause encephalitis, by gaining access to neurons in the central nervous system through the infection of an olfactory nerve or the penetration of the blood-brain barrier, the molecular mechanisms of MVEV/SLEV infection of cells such as DCs, lymph nodes, visceral organs, nerves, and blood endothelium remain unknown. In the case of JEV, histopathological changes are observed in the lung, kidney, and liver of JE patients [4], but there is no evidence that JEV follows an infectious sequence in the human body that is similar to that of MVEV or SLEV in rodents.

Calcium-dependent (C-type) lectins are transmembrane proteins that are displayed primarily on antigen-presenting cells, where the molecules exhibit calcium-dependent recognition of specific carbohydrates on glycoconjugates. C-type lectins recognize endogenous ligands, mediating cell-cell interactions during immune responses and contributing to the maintenance of endogenous glycoprotein homeostasis [5]. In cooperation with Toll-like receptors, C-type lectins also function as pathogen recognition receptors for the innate and adaptive immune responses [5]. In some contexts, however, C-type lectins have been reported as receptors used by pathogens including viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi for the invasion of cells [6].

One of the best-characterized C-type lectins is DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN); a molecule that is expressed in immature DCs and a subpopulation of macrophages [7]. Usage of DC-SIGN in viral infection has been reported for WNV [8], DV [9–11], and other viruses. Furthermore, nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter region of the DC-SIGN-encoding gene are associated with the severity of diseases caused by DV [12], indicating an important role of DC-SIGN in DV pathogenesis. Given that WNV and DV are mosquito-borne viruses, the use of DC-SIGN as a receptor is most likely to occur following a mosquito bite, when the immature DCs residing in the skin become infected. It is also reported that the two viruses use DC-SIGNR [8, 11], which shares 77 % amino acid sequence identity with DC-SIGN, to infect the endothelium of lymph nodes and liver sinusoids [7]. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell lectin (LSECtin) is a recently-identified C-type lectin [13] that is involved in the infections of a number of viruses, including filoviruses, SARS coronavirus, Lassa virus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [14–16].

In the present study, as a first step towards characterizing the in vivo dynamics of JEV, we have examined the relationship between JEV infection in vitro and three human C-type lectins: DC-SIGN, DC-SIGNR, and LSECtin. While each of these lectins conferred susceptibility to JEV infection to cells, they each produced distinct effects.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Murine anti-DC-SIGN(R) (clone 120612), murine anti-LSECtin (SOTO-1) and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 were purchased from R&D Systems, Santa Cruz Biotech, and Molecular Probes, respectively. Murine anti-feline CD2 (clone SKR2) was reported previously [17]. D1-4G2-4-15 (against flavivirus group antigen, [18]) hybridoma, yeast mannan, and N-acetylglucosamine β1-2 mannose (GlcNAcβ1-2Man disaccharide) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Sigma, and Dextra Laboratories, respectively.

Cells and virus

Vero9013 (Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank 9013), A549 (ATCC CCL-185), HeLa (ATCC CCL-2), 293 (ATCC CRL1573), HT1080 (ATCC CCL121) and C6/36 (ATCC CRL1660) cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma). Daudi (ATCC CCL-213) and Jurkat (Clone E6-1, TIB-152) cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Sigma). Both media were supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) and the antibiotics penicillin and streptomycin. C6/36 cells were incubated at 28 °C; other cell lines were incubated at 37 °C. This study used a genotype I strain of JEV (JEV/sw/Chiba/88/2002), which had been isolated from a pig in Japan in 2002. Titration was performed as a conventional plaque assay with Vero9013 cells [19].

Expression of C-type lectin genes

The genes encoding human lectins were expressed using lentiviral vectors as described previously [20]. A lentivirus harboring a gene encoding the feline CD2 molecule without its cytoplasmic tail (fCD2∆CT) [17] was used as a control vector. Daudi cells infected with the lentiviral vectors were maintained in the presence of 0.3 μg of puromycin (InvivoGen) per ml.

Flow cytometry

Cells were washed once with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 2 % FCS and 0.1 % sodium azide (wash buffer) and incubated with antibodies on ice for 20 min. After washing in wash buffer, the cells were further incubated with secondary antibodies. Stained cells were analyzed by Cyflow space with FloMax software (Partec). For the virus-binding assay, cells were incubated with JEV on ice for 90 min before staining with antibodies. For intracellular staining of viral proteins, reactions with antibodies were performed in the presence of 0.1 % saponin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Indirect fluorescence assay

Cells were washed with PBS, smeared on glass slides, and then fixed with acetone. The cells were incubated with antibodies for 30 min at 37 °C and washed with PBS. The cells were then further incubated with secondary antibodies for 30 min at 37 °C and washed with PBS. The stained cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Carbohydrates of JEV proteins

Reactivity with plant lectins and susceptibility to endoglycosidases of JEV proteins were analyzed using a DIG Glycan Differentiation Kit (Roche Applied Science) or by using endoglycosidase H and PNGase F (New England Biolabs) and western blotting.

Results

Growth of JEV in primate cell lines

To explore the relationship between JEV infection and human C-type lectins, we compared JEV growth in six human cell lines (293, HeLa, HT1080, A549, Jurkat, and Daudi) and one monkey cell line (Vero9013). The primate cells were infected with JEV prepared in mosquito cells (C6/36), at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.02. With the exception of the Daudi cells, JEV titers in the cell lines reached over 106 plaque-forming units (PFUs)/ml by 72 hours postinfection (hpi; Fig. 1). In contrast, JEV was undetectable in Daudi cells during the culture period (Fig. 1; the detection limit is 5 PFUs/ml). Daudi cells were thus selected for use as a non-permissive host for the following experiments, which tested the role of exogenously expressed C-type lectins.

Daudi cells were infected separately with lentiviral vectors that encoded fCD2∆CT (control), DC-SIGN, DC-SIGNR, or LSECtin and cultured in the presence of puromycin. Flow cytometric analysis revealed greater than 98 % positivity for each molecule and similar levels of DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR (data not shown). The Daudi cells were infected with C6/36-derived JEV at an MOI of 0.02 and cultured. The culture supernatants were then titrated. As shown in Fig. 2A, growth of JEV was detectable in DC-SIGN-, DC-SIGNR-, and LSECtin-expressing Daudi cells, but not in control-molecule-expressing Daudi cells. Titers plateaued at 24 hpi in DC-SIGN-expressing Daudi cells and at 36 hpi in DC-SIGNR-expressing Daudi cells. In LSECtin-expressing Daudi cells, titers were low at early hpi but continued to increase. At 72 hpi, titers were higher than those in DC-SIGN-expressing cells. At each time point, titers were higher in Daudi cells harboring DC-SIGNR than in those harboring DC-SIGN or LSECtin.

Growth of JEV in fCD2∆CT-, DC-SIGN-, DC-SIGNR-, and LSECtin-expressing Daudi cells. A. Daudi cells were infected with C6/36-derived virus at a multiplicity of infection of 0.02, and culture supernatants were then titrated in Vero9013 cells. *, undetectable (the detection limit is 5 PFUs/ml). Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). B. Intracellular viral antigens were examined by indirect fluorescence assay with 4G2 antibody. hpi, hours postinfection

JEV antigen in the inoculated Daudi cells was detected by indirect fluorescence assay with the anti-envelope antibody 4G2 [18]. In control-molecule-expressing Daudi cells, JEV antigen was not detectable at any time point (Fig. 2B, uppermost panels). A small population of DC-SIGN-expressing Daudi cells (less than 1 %) was antigen positive at 24 hpi, but no apparent increase in the frequency of JEV positivity was observed thereafter (Fig. 2B, second upper panels). Approximately 30 % of DC-SIGNR-expressing Daudi cells were positive for JEV antigen at 24 hpi; the frequency of JEV positivity increased at 48 and 72 hpi in these cells (Fig. 2B, second lower panels). In LSECtin-expressing Daudi cells, a small population became antigen-positive at 24 hpi, and the positivity gradually increased as the culture period progressed (Fig. 2B, lowest panels).

These results indicated two things: (1) that both DC-SIGNR and LSECtin expression led to proliferation of JEV in Daudi cells (to differing degrees); and (2) that DC-SIGN expression conferred susceptibility to infection by C6/36-derived JEV, but not Daudi-derived JEV, in Daudi cells.

Comparison of JEV grown in insect and mammalian cells

To focus on early events during JEV infection in Daudi cells, inoculation of C6/36-derived JEV was performed at an MOI of 2, and antigen levels within the cells were analyzed at 12 hpi by flow cytometry. As expected, Daudi cells expressing any of the three lectins showed an increase in JEV antigen-positive cell numbers after inoculation with C6/36-derived JEV (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the increase was highest in DC-SIGNR-expressing Daudi cells, followed in order by DC-SIGN- and LSECtin-expressing cells (Fig. 3A). This is consistent with the JEV growth curves in Daudi cells during the early phase at 12-36 hpi (Fig. 2A).

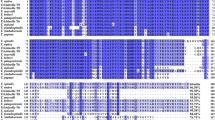

Infectivity in Daudi cells of JEV prepared in various cell lines. JEV was grown in C6/36 (A), Vero (B), A549 (C), and 293 (D) cell lines and used for infection. Infection was performed at a multiplicity of infection of 2, and intracellular viral antigen was detected 12 hours postinfection by flow cytometry. Data for each of the infected cell types were compared to values obtained for mock-infected cells and are shown as % positivity. Results from three independent experiments are indicated

The results described above (Figs. 2, 3A) suggested that the degree of JEV proliferation in the inoculated cells was not only dependent on the specific lectin expressed, but also on the cell line that had been used to prepare JEV. Consequently, JEV was grown for use in infection in three mammalian cells: Vero9013 (monkey), A549 (human), and 293 (human). The results were generally similar when C6/36-derived JEV was compared with Vero9013- and A549-derived JEVs (Fig. 3B, C). When 293-derived JEV was used, both DC-SIGN and LSECtin expression resulted in an increase in the number of antigen-positive Daudi cells, but the effect was the opposite of that observed for infection with JEV derived from C6/36, Vero9013, and A549 cells. LSECtin-expressing Daudi cells showed a greater increase in the number of antigen-positive cells than DC-SIGN-expressing Daudi cells when infected with JEV derived from 293 cells (Fig. 3D). However, when infected with JEV derived from C6/36, Vero, and A549 cells, LSECtin-expressing Daudi cells showed less of an increase in the number of antigen-positive cells than DC-SIGN-expressing Daudi cells in each of three independent experiments (Fig. 3A-C). Thus, while each of the three lectins increased the susceptibility of Daudi cells to JEV infection, the host cells in which JEV was prepared affected the degree of susceptibility.

Comparison of surface proteins of JEV grown in C6/36 and 293 cells

The effects of C-type lectins on infection are generally based on the recognition of carbohydrates on the virion surface by the carbohydrate-recognition domains (CRDs) of C-type lectins. The results shown in Fig. 3 led us to examine the glycosylation of the major envelope (E, approximately 50 kDa) and minor precursor M (prM, approximately 25 kDa) proteins of purified JEVs that had been grown in C6/36 and 293 cells [21]. Western blotting with Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA) lectin, which binds high-mannose N-glycan structures, detected proteins with a molecular weight (MW) of approximately 50 kDa (Fig. 4A). The detected bands were confirmed to be E proteins by the use of an E-specific antibody (Fig. 4B). No reactivity to E proteins was observed for the other plant lectins that were examined, namely Sambucus nigra agglutinin, Peanut agglutinin, and Datura stramonium agglutinin (data not shown). A small amount of uncleaved prM on JEV particles may have the potential to be involved in C-type-lectin-mediated viral infection due to N-glycosylation motifs within its deduced peptide sequence [21]. Molecules corresponding in size to prM (25 kDa) were not detected with any of the four plant lectins. Further analysis of carbohydrate modifications focused on the E protein because a JEV prM-specific antibody was not available. Pretreatment with either endoglycosidase H (to remove high-mannose or hybrid N-linked oligosaccharides) or PNGase F (to remove all N-linked oligosaccharides), reduced the MW of the E proteins of C6/36-derived JEV, as observed by western blotting. However, the effect of endoglycosidase H was very small (Fig. 4C, left panel). A similar reduction in the MW of the E protein after endoglycosidase treatment was observed with 293-derived JEV (Fig. 4C, right panel).

Characterization of surface proteins of JEV prepared in C6/36 and 293 cell lines. A. Reactivity with Galanthus nivalis agglutinin specific for high-mannose N-glycan structures. B. Molecular weights of envelope (E) proteins detected by anti-E antibody. C. Molecular weights of E proteins pretreated with EndoH or PNGaseF (Endo+ and PNGaseF+). EndoH− and PNGaseF− indicate mock-treatment in buffers specific for each glycosidase

These results indicated that, although JEV E proteins prepared in C6/36 and 293 cells were of different MW, suggesting a different modification of E in each of the two cell lines, both had N-linked, high-mannose structures. The results also indicate that prM carrying high-mannose structures was absent or undetectable in C6/36- and 293-derived JEV preparations.

Sugar effects on JEV binding/infection in lectin-expressing Daudi cells

The enhanced binding of viral particles to the cell surface is a known effect of DC-SIGN- and/or DC-SIGNR expression that occurs in human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and Ebola virus infections [22–24]. We therefore used flow cytometry to examine whether the enhanced growth of JEV in Daudi cells caused by lectin expression (Fig. 2A) was associated with viral binding. Daudi cells were first incubated on ice with C6/36-derived JEV at an MOI of 0, 1, 10, 100, or 1,000. JEV antigens on the cell surface were then detected using the 4G2 antibody. As shown in Fig. 5A (second upper and second lower panels), JEV binding was detected with DC-SIGN- and DC-SIGNR-expressing Daudi cells at MOIs of 100 and 1,000, with higher positivity observed in DC-SIGNR-expressing Daudi cells than in DC-SIGN-expressing Daudi cells. JEV binding was not measureable in LSECtin-expressing Daudi cells (Fig. 5A, lower panels).

JEV binding/infection and carbohydrates. A. Daudi cells were incubated on ice with JEV at the indicated multiplicity of infection, and viral antigen on the cell surface was analyzed by flow cytometry. Gating for % positivity was set to make the value less than 1 % in normal cells without virus. B. DC-SIGN- and DC-SIGNR-expressing Daudi cells were preincubated with carbohydrates at the indicated concentrations and used for the virus binding assay by flow cytometry. Calculation of % control was as follows: (mean fluorescence intensity in the presence of carbohydrate)/(mean fluorescence intensity in the absence of carbohydrate) × 100. Data are means of duplicate experiments. C. Cells were preincubated with 100 μg of the indicated carbohydrates per ml and used for infection at a multiplicity of infection of 2. Intracellular viral antigen was detected at 12 hours postinfection by flow cytometry. % control was calculated as follows: (% positivity in the presence of carbohydrate)/(% positivity in the absence of carbohydrate) × 100. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments

DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR bind specific carbohydrates of glycoconjugates, mainly high-mannose structures. Their binding can be blocked by mannan, a polymer of mannose [5]. To examine whether the observed binding between JEV and DC-SIGN/DC-SIGNR was carbohydrate specific, Daudi cells were pre-incubated on ice for 30 min with mannan or GlcNAcβ1-2Man (a target specific for LSECtin) at the indicated concentrations and used for virus binding assays. As shown in Fig. 5B, the binding between JEV and DC-SIGN/DC-SIGNR was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by mannan, but not by the control carbohydrate. The concentrations needed to inhibit binding were higher for DC-SIGNR than they were for DC-SIGN.

Daudi cells pre-treated with 100 μg of mannan or GlcNAcβ1-2Man per ml were inoculated with JEV at an MOI of 2, and analyzed for the presence of antigen-positive cells at 12 hpi by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 5C, DC-SIGN- and DC-SIGNR-mediated infection was dramatically reduced by treatment with mannan, but not GlcNAcβ1-2Man. In contrast, LSECtin-mediated infection was reduced by treatment with GlcNAcβ1-2Man, but not mannan (Fig. 5C). Thus, it is likely that the effects of DC-SIGN/DC-SIGNR on JEV infection were due to the enhanced binding of JEV on lectin-expressing cells via specific carbohydrates. Although binding of the virus to LSECtin-expressing cells was not detected, the observed inhibition of infection by GlcNAcβ1-2Man strongly suggested that the effect of LSECtin on JEV infection was caused by a direct interaction with a specific carbohydrate(s) on JEV surface proteins.

Discussion

The effects of C-type lectins on infection are generally based on the recognition of carbohydrates on the surface of viral particles. JEV has two surface glycoproteins, the major protein E and the minor protein prM [1]. To our knowledge, all but one of the JEV isolates whose E- and prM-encoding sequences have been determined have one N-glycosylation motif in each deduced peptide sequence. The one known exception is Indonesia isolate JKT6468, which harbors two motifs in its predicted prM protein [25]. Furthermore, in the present study, the JEV-infection-enhancing effects of three C-type lectins (DC-SIGN, DC-SIGNR, and LSECtin) were inhibited by cognate carbohydrates. Thus, even though only a single JEV isolate was used, the involvement of the three C-type lectins in JEV infection reported here can likely be considered to be a general characteristic of JEV.

That the related lectins DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR were found to enhance binding of JEV to cells and viral proliferation in the cells, and that the enhancing effects of DC-SIGN, but not DC-SIGNR, were found to depend on the cell type in which the virus was grown is reminiscent of the characteristics of WNV and DV [8, 26]. In the case of WNV and DV, DC-SIGN usage has been shown to be strongly related to cell origin. Insect-cell-derived, but not mammalian-cell-derived, viruses efficiently use DC-SIGN in infection. This difference is caused by carbohydrate modifications that differ according to the origin of the virus-producing cells [8, 26]. One exception is that WNV grown in Vero cells uses DC-SIGN [8]. In the present study, JEV prepared in an insect cell line used DC-SIGN efficiently, as did JEV prepared in some mammalian cell lines (including Vero and A549). Usage of DC-SIGN by mammalian-cell-derived JEV (Fig. 3B, C) may indicate the existence of specific cell types in the human body that produce JEV with the ability to use DC-SIGN in infection. However, because the glycan structures and glycosylation levels exhibited by tumor cells frequently differ from those of normal cells [27], DC-SIGN usage by mammalian-cell-derived JEV/WNV might not be observed in vivo. Studies with primary cell cultures from various human organs will be required to better characterize the effects of carbohydrate modifications on viral infectivity. Nevertheless, the carbohydrate status of the viral surface proteins of JEV prepared in insect C6/36 cells and mammalian 293 cells was tentatively compared to clarify their relationship to DC-SIGN usage. The results that were obtained suggest that while DC-SIGN usage by JEV is mediated by high-mannose structures on the E protein, the interaction between DC-SIGN and high-mannose structures could have been inhibited by structural hindrance of other modifications of the E protein or other unknown mechanisms. The prM protein does not seem to be significantly involved in DC-SIGN usage, due to the lack of a high-mannose structure and its absence within the JEV virion.

DC-SIGN is expressed in immature DCs and a subpopulation of macrophages [7]. Our finding that insect-cell-derived JEV efficiently binds to and infects DC-SIGN-expressing cells, suggests that JEV injected by mosquito bites goes toward DC-SIGN-expressing DCs/macrophages in the skin as a first target of infection, which is similar to WNV and DV [8, 26]. DC-SIGNR is typically detected in liver and lymph node sinusoidal endothelial cells and in alveolar and placental endothelial cells [7, 28]. Our results indicate that such cells can be highly susceptible to JEV infection produced from a range of hosts and cell types, and therefore that they might be major replication sites for JEV before brain invasion in vivo. Abortion and histopathological changes in the liver and lung caused by infection [4], virus isolation from the liver and placenta [29], and placenta susceptibility to infection in vitro [30] may occur due to the distribution of DC-SIGNR. Liver and lymph node sinusoidal endothelial cells also express LSECtin [13], which was shown by the authors to enhance JEV infection. The infection-enhancing effects of DC-SIGNR and LSECtin were mediated by distinct N-glycans, high-mannose and GlcNAcβ1-2Man, respectively. Thus, in the case of JEV infection, the two lectins are able to function synergistically on liver and lymph node sinusoidal endothelial cells.

A major characteristic of JE observed in JEV-infected humans and horses is encephalitis, but none of the three C-type lectins described here are known to be expressed in the brain. The three C-type lectins perhaps contribute to viscero-organ tropisms and/or proliferation before brain invasion. Furthermore, we could not detect expression of any of the lectins in mammalian Vero, A549, HeLa, 293, and HT1080 cell lines in which JEV proliferated well (Fig. 1). C-type lectin-independent infection seems to be mediated by many molecules, such as laminin receptors, heat shock (cognate) receptors, and αVβ3 integrin [31].

References

Lindenbach BD, Murray CL, Thiel HJ, Rice CM (2013) Flaviviridae. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM (eds) Fields virology, 6th edn. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 712–746

McMinn PC, Dalgarno L, Weir RC (1996) A comparison of the spread of Murray Valley encephalitis viruses of high or low neuroinvasiveness in the tissues of Swiss mice after peripheral inoculation. Virology 220:414–423

Monath TP, Cropp CB, Harrison AK (1983) Mode of entry of a neurotropic arbovirus into the central nervous system. Lab Invest 48:399–410

Mukherji AK, Biswas SK (1976) Histopathological studies of brains (and other viscera) from cases of JE virus encephalitis during 1973 epidemic at Bankura. Indian J Med Res 64:1143–1149

van Kooyk Y (2009) C-type lectin receptors on dendritic cells. In: Vasta GR, Ahmed H (eds) Animal lectins. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Florida, pp 351–361

van den Berg LM, Gringhuis SI, Geijtenbeek TBH (2012) An evolutionary perspective on C-type lectins in infection and immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1253:149–158

Soilleux EJ (2003) DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific ICAM-grabbing non-integrin) and DC-SIGN-related (DC-SIGNR): friend or foe? Clin Sci (Lond) 104:437–446

Davis CW, Nguyen HY, Hanna SL, Sánchez MD, Doms RW, Pierson TC (2006) West Nile virus discriminates between DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR for cellular attachment and infection. J Virol 80:1290–1301

Hacker K, White L, de Silva AM (2009) N-linked glycans on dengue viruses grown in mammalian and insect cells. J Gen Virol 90:2097–2106

Navarro-Sanchez E, Altmeyer R, Amara A, Schwartz O, Fieschi F, Virelizier JL, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Desprès P (2003) Dendritic-cell-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin is essential for the productive infection of human dendritic cells by mosquito-cell-derived dengue viruses. EMBO Rep 4:723–728

Tassaneetrithep B, Burgess TH, Granelli-Piperno A, Trumpfheller C, Finke J, Sun W, Eller MA, Pattanapanyasat K, Sarasombath S, Birx DL, Steinman RM, Schlesinger S, Marovich MA (2003) DC-SIGN (CD209) mediates dengue virus infection of human dendritic cells. J Exp Med 197:823–829

Sakuntabhai A, Turbpaiboon C, Casadémont I, Chuansumrit A, Lowhnoo T, Kajaste-Rudnitski A, Kalayanarooj SM, Tangnararatchakit K, Tangthawornchaikul N, Vasanawathana S, Chaiyaratana W, Yenchitsomanus P, Suriyaphol P, Avirutnan P, Chokephaibulkit K, Matsuda F, Yoksan S, Jacob Y, Lathrop GM, Malasit P, Desprès P, Julier C (2005) A variant in the CD209 promoter is associated with severity of dengue disease. Nat Genet 37:507–513

Liu H, Chiou SS, Chen WJ (2004) Differential binding efficiency between the envelope protein of Japanese encephalitis virus variants and heparan sulfate on the cell surface. J Med Virol 72:618–624

Gramberg T, Hofmann H, Möller P, Lalor PF, Marzi A, Geier M, Krumbiegel M, Winkler T, Kirchhoff F, Adams DH, Becker S, Münch J, Pöhlmann S (2005) LSECtin interacts with filovirus glycoproteins and the spike protein of SARS coronavirus. Virology 340:224–236

Shimojima M, Ströher U, Ebihara H, Feldmann H, Kawaoka Y (2012) Identification of cell surface molecules involved in dystroglycan-independent Lassa virus cell entry. J Virol 86:2067–2078

Shimojima M, Kawaoka Y (2012) Cell surface molecules involved in infection mediated by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein. J Vet Med Sci 74:1363–1366

Shimojima M, Nishimura Y, Miyazawa T, Kato K, Nakamura K, Izumiya Y, Akashi H, Tohya Y (2002) A feline CD2 homologue interacts with human red blood cells. Immunology 105:360–366

Henchal EA, Gentry MK, McCown JM, Brandt WE (1982) Dengue virus-specific and flavivirus group determinants identified with monoclonal antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence. Am J Trop Med Hyg 31:830–836

Ohno Y, Sato H, Suzuki K, Yokoyama M, Uni S, Shibasaki T, Sashika M, Inokuma H, Kai K, Maeda K (2009) Detection of antibodies against Japanese encephalitis virus in raccoons, raccoon dogs and wild boars in Japan. J Vet Med Sci 71:1035–1039

Shimojima M, Ikeda Y, Kawaoka Y (2007) The mechanism of Axl-mediated Ebola virus infection. J Infect Dis 196:S259–S263

Kim JM, Yun SI, Song BH, Hahn YS, Lee CH, Oh HW, Lee YM (2008) A single N-linked glycosylation site in the Japanese encephalitis virus prM protein is critical for cell type-specific prM protein biogenesis, virus particle release, and pathogenicity in mice. J Virol 82:7846–7862

Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Middel J, Cornelissen IL, Nottet HS, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y (2000) DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell 100:587–597

Lozach PY, Lortat-Jacob H, de Lacroix de Lavalette A, Staropoli I, Foung S, Amara A, Houlès C, Fieschi F, Schwartz O, Virelizier JL, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Altmeyer R (2003) DC-SIGN and L-SIGN are high affinity binding receptors for hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E2. J Biol Chem 278:20358–20366

Alvarez CP, Lasala F, Carrillo J, Muñiz O, Corbí AL, Delgado R (2002) C-type lectins DC-SIGN and L-SIGN mediate cellular entry by Ebola virus in cis and in trans. J Virol 76:6841–6844

Han KK, Martinage AM (1992) Possible relationship between coding recognition amino acid sequence motif or residue(s) and post-translational chemical modification of proteins. Int J Biochem 24:1349–1363

Dejnirattisai W, Webb AI, Chan V, Jumnainsong A, Davidson A, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton G (2011) Lectin switching during dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis 203:1775–1783

Dube DH, Bertozzi CR (2005) Glycans in cancer and inflammation–potential for therapeutics and diagnostics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4:477–488

Jeffers SA, Tusell SM, Gillim-Ross L, Hemmila EM, Achenbach JE, Babcock GJ, Thomas WD Jr, Thackray LB, Young MD, Mason RJ, Ambrosino DM, Wentworth DE, DeMartini JC, Holmes KV (2004) CD209L (L-SIGN) is a receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:15748–15753

Chaturvedi UC, Mathur A, Chandra A, Das SK, Tandon HO, Singh UK (1980) Transplacental infection with Japanese encephalitis virus. J Infect Dis 141:712–715

Bhonde RR, Wagh UV (1985) Susceptibility of human placenta to Japanese encephalitis virus in vitro. Indian J Med Res 82:371–373

Thongtan T, Wikan N, Wintachai P, Rattanarungsan C, Srisomsap C, Cheepsunthorn P, Smith DR (2012) Characterization of putative Japanese encephalitis virus receptor molecules on microglial cells. J Med Virol 84:615–623

Acknowledgments

JEV/sw/Chiba/88/2002 was kindly provided by Dr. Tomohiko Takasaki (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan). This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (21580374) and Young Scientists (B) (23780294) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and by a grant for Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (H20-Shinko-Ippan-003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shimojima, M., Takenouchi, A., Shimoda, H. et al. Distinct usage of three C-type lectins by Japanese encephalitis virus: DC-SIGN, DC-SIGNR, and LSECtin. Arch Virol 159, 2023–2031 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-014-2042-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-014-2042-2