Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine the associations between self-reported spiritual/religious concerns and age, gender, and emotional challenges among cancer survivors who have completed a 5-day rehabilitation course at a rehabilitation center in Denmark (the former RehabiliteringsCenter Dallund (RC Dallund)).

Methods

The data stem from the so-called Dallund Scale which was adapted from the NCCN Distress Thermometer and comprised questions to identify problems and concerns of a physical, psychosocial, and spiritual/religious nature. Descriptive statistics were performed using means for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Odds ratios were calculated by logistic regression.

Results

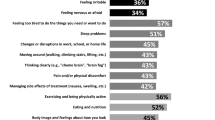

In total, 6640 participants filled in the questionnaire. Among participants, 21% reported one or more spiritual/religious concerns, the most reported concerns related to existence and guilt. Having one or more spiritual/religious concerns was significantly associated with age (OR 0.88), female gender (OR 1.38), and by those reporting emotional problems such as being without hope (OR 2.51), depressed (OR 1.49), and/or anxious (OR 1.95). Among participants, 8% stated they needed help concerning spiritual/religious concerns.

Conclusions

Cancer patients, living in a highly secular country, report a significant frequency of spiritual/religious and existential concerns. Such concerns are mostly reported by the young, female survivors and by those reporting emotional challenges. Spiritual/religious and existential concerns are often times tabooed in secular societies, despite being present in patients. Our results call for an increased systemic attention among health professionals to these concerns, and a particular focus on identifying and meeting the spiritual/religious and existential concerns of women, the young and those challenged by hopelessness, depression, and anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. National Academies Press

Henoch I, Danielson E (2008) Existential concerns among patients with cancer and interventions to meet them: an integrative literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 18(3):225–236

Assing Hvidt E (2015) The existential cancer journey: travelling through the intersubjective structure of homeworld/alienworld. Health. 21:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459315617312

Park CL (2012) Meaning making in cancer survivorship. In: Wong PTP (ed) The human quest for meaning. Theories, research and applications, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Breitbart W (2002) Spirituality and meaning in supportive care: spirituality- and meaning-centered group psychotherapy interventions in advanced Cancer. Support Care Cancer 10(4):272–280

Kristeller JL, Rhodes M, Cripe LD, Sheets V (2005) Oncologist assisted spiritual intervention study (OASIS): patient acceptability and initial evidence of effects. Int J Psychiatry Med 35(4):329–347

Zuckerman P (2008) Society without God : what the least religious nations can tell us about contentment. New York University Press, New York

Gundelach P (2011) Små og store forandringer danskernes værdier siden 1981. Hans Reitzels Forlag, Copenhagen

Rosen I (2009) I'm a believer - but I'll be damned if I’m religious. In: Belief and religion in the Greater Copenhagen area - a focus group study. Lund studies in Sociology of Religion. Lunds Universitet

Assing Hvidt E, Iversen HR, Hansen HP (2013) “Someone to hold the hand over me”: the significance of transpersonal “attachment” relationships of Danish cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care 22(6):726–737

Assing Hvidt E (2013) Sources of ‘relational homes’ - a qualitative study of cancer survivors’ perceptions of emotional support. Ment Health Relig Cult 16(6):617–632

Johannessen-Henry CT, Deltour I, Bidstrup PE, Dalton SO, Johansen C (2013) Associations between faith, distress and mental adjustment – a Danish survivorship study. Acta Oncol 52(2):364–371. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.744141

Hvidtjorn D, Hjelmborg J, Skytthe A, Christensen K, Hvidt NC (2014) Religiousness and religious coping in a secular society: the gender perspective. J Relig Health 53(5):1329–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9724-z

Trzebiatowska M, Bruce S (2012) Why are women more religious than men? 1st edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dein S, Cook CC, Koenig H (2012) Religion, spirituality, and mental health: current controversies and future directions. J Nerv Ment Dis 200(10):852–855. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31826b6dle

World Health Organization. International classification of functioning disability and health (ICF). 2001. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/. Accessed 23.10.13 2013.

Manning-Walsh J (2005) Spiritual struggle: effect on quality of life and life satisfaction in women with breast cancer. J Holist Nurs 23(2):120–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010104272019

Pargament KI, Desai KM, McConnell KM (2006) Spirituality: a pathway to posttraumatic growth or decline? In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG (eds) Handbook of posttraumatic growth : research and practice. Mahwah, N.J. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp 121–137

Fitchett G, Risk JL (2009) Screening for spiritual struggle. J Pastoral Care Counsel 63(1–2):4–1-12

Hansen H, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T (2008) Cancer rehabilitation in Denmark: the growth of a new narrative. Med Anthropol Q 22(4):360–380

Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T, Hansen HP (2013) The ritualization of rehabilitation. Med Anthropol 32(3):266–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2011.637255

Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, Peabody E, Scher HI, Holland JC (1998) Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma. Cancer 82(10):1904–1908. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-X

Donovan KA, Grassi L, McGinty HL, Jacobsen PB (2014) Validation of the distress thermometer worldwide: state of the science. Psycho-Oncology. 23(3):241–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3430

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN distress thermometer and problem list. 2018. https://www.nccn.org/about/permissions/thermometer.aspx. Accessed 04 Nov 2018.

Kristensen T. Dallundskalaen. [Visitation of cancer patients to a rehabilitation, Project anno 2004] Visitation af kræftpatienter til rehabilitering, projekt årgang 2004. Søndersø: RehabiliteringsCenter Dallund2005.

Kristensen T, Hjortebjerg U, Larsen S, Mark K, Tofte J, Piester CB (2004) Rehabilitation after Cancer: 30 statements evaluated by more than 1.000 patients. Psycho-Oncology. 13:178 (poster)

Armstrong RA (2014) When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 34(5):502–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12131.

Strang P (1997) Existential consequences of unrelieved cancer pain. Palliat Med 11:299–305

Hansen HP, Tjornhoj-Thomsen T, Johansen C (2011) Rehabilitation interventions for cancer survivors: the influence of context. Acta Oncol 50(2):259–264. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2010.529460

Rosedale M (2009) Survivor loneliness of women following breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 36(2):175–183

Assing Hvidt E, Iversen HR, Hansen HP (2012) Belief and meaning orientations among Danish cancer patients in rehabilitation. A Taylorian perspective. Spiritual Care 1(3):1–22

la Cour P (2008) Existential and religious issues when admitted to hospital in a secular society: patterns of change. Ment Health Relig Cult 11(8):769–782

Strang S, Strang P, Ternestedt BM (2002) Spiritual needs as defined by Swedish nursing staff. J Clin Nurs 11(1):48–57. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00569.x

Klemm P, Miller MA, Fernsler J (2000) Demands of illness in people treated for colorectal cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 27(4):633–639

Fitchett G, Murphy PE, Kim J, Gibbons JL, Cameron JR, Davis JA (2004) Religious struggle - prevalence, correlates and mental health risks in diabetic, congestive heart failure, and oncology patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 34(2):179–196

King SD, Fitchett G, Murphy PE, Pargament KI, Martin PJ, Johnson RH, Harrison DA, Loggers ET (2017) Spiritual or religious struggle in hematopoietic cell transplant survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 26(2):270–277

Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D (2002) Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 24(1):49–58

Crockett A, Voas D (2006) Generations of decline: religious change in 20th-century britain. J Sci Study Relig 45(4):567–584

Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P (2005) Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs 49(6):616–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x

Eakin EG, Strycker LA (2001) Awareness and barriers to use of cancer support and information resources by HMO patients with breast, prostate, or colon cancer: patient and provider perspectives. Psychooncology. 10(2):103–113

Koenig HG (1994) Religion and hope. Religion in aging and health: theoretical foundations and methodological frontiers, pp 18–51

Hvidt NC, Hvidtjørn D, Christensen K, Nielsen JB, Sondergaard J (2016) Faith moves mountains-mountains move faith: two opposite epidemiological forces in research on religion and health. J Relig Health 56:294–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0300-1

Ahrenfeldt LJ, Möller S, Andersen-Ranberg K, Vitved AR, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Hvidt NC (2017) Religiousness and health in Europe. Eur J Epidemiol 32(10):921–929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0296-1

la Cour P, Hvidt NC (2010) Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Soc Sci Med 71(7):1292–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.024

Assing Hvidt E, Søndergaard J, Gulbrandsen P, Ammentorp J, Timmermann C, Hvidt NC (2018) ‘We are the barriers’: Danish general practitioners’ interpretations of why the existential and spiritual dimensions are neglected in patient care. Commun Med 14(2):108–120. https://doi.org/10.1558/cam.32147

Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, Epstein-Peterson ZD, Tseng YD, Mitchell C et al. Nurse and Physician Barriers to Spiritual Care Provision at the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.020

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Danish Cancer Society for the many decades they have financed the Rehabilitation Centre Dallund, where all data of this study was collected, and to thank all the cancer survivors who participated in the study. We also wish to thank Tom Kristensen who developed the Dallund scale.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hvidt, N.C., Mikkelsen, T.B., Zwisler, A.D. et al. Spiritual, religious, and existential concerns of cancer survivors in a secular country with focus on age, gender, and emotional challenges. Support Care Cancer 27, 4713–4721 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04775-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04775-4