Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the study is to evaluate the feasibility of a self-help web-based intervention to alleviate sexual problems and fertility distress in adolescents and young adults with cancer.

Methods

Twenty-three persons with cancer (19 women and 4 men, age 18–43, 1–5 years post-diagnosis of lymphoma, breast, gynecologic, central nervous system, or testicular cancer) were recruited to test a 2-month web-based program targeting sexual problems or fertility distress. The programs were organized in modules with educational and behavior change content, including texts, illustrations, exercises, and video vignettes. The program also included a discussion forum and an “ask the expert” forum. In addition, the sexuality program offered two telephone consultations. Feasibility (regarding demand, acceptability, preliminary efficacy, and functionality) was evaluated with the website system data, telephone interviews, continuous online evaluations, and study-specific measures.

Results

Fifteen participants completed four modules or more. Most of the program features were used and well accepted by these “committed users.” The web-based format enabled flexible use by participants with diverse needs. Preliminary efficacy was indicated by self-reported increased knowledge and skill in handling sexual problems and fertility distress. The website was easy to use and functioned well technically.

Conclusions

The present study indicated that this web-based intervention was feasible for adolescents and young adults with cancer. The effectiveness of the intervention in decreasing sexual problems and fertility distress will be tested in a population-based randomized controlled trial for adolescents and young adults with cancer.

Trial registration: ISRCTN36621459.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The majority of adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer will experience a negative impact on their sexuality or fertility in the aftermath of their cancer treatment [1, 2]. The extent of the problems depends on the type of cancer and treatment and age at diagnosis, as well as time since diagnosis. Commonly reported sexual problems include lack of desire, orgasm and arousal difficulties, vaginal dryness (women), pain, and erection and ejaculatory dysfunction (men) [3]. Existing results indicate that up to 50% of young men [4] and women [5] treated for cancer experience a negative impact on their sexual life and intimacy. Among survivors of cancer at a young age, the overall probability of parenthood is reduced by 23–50% [6, 7]. In a study by Gorman et al. [8], 65% of female survivors reported moderate or high levels of distress related to concerns about their fertility potential, personal health, health risks of potential future children, and disclosure issues. Importantly, reproductive concerns were associated with consistent long-term depressive symptoms. Furthermore, it is described that AYAs with cancer in contact with health care professionals receive insufficient information and support related to sexuality and reproduction [9, 10]. In a population-based study of survivors who had received cancer treatment at age 18–45, 48% of the women and 20% of the men reported not having received any information about treatment-related risks of infertility [11].

In health care, web-based interventions have the potential to increase participants’ sense of autonomy (control over one’s life), perceived efficacy (competence), and relatedness (“I am not alone with these problems”) [12]. Web-based interventions are increasingly being used to provide education and support to mitigate psychosocial problems in AYAs with cancer [13]. However, such interventions in the areas of sexual and reproductive health for young cancer patients are scarce. One educational program that provided information about risk of treatment-induced infertility and having children after breast cancer has been positively evaluated [14]. Additionally, Schover et al. [15] reported promising results from an efficacy trial that tested an intervention for cancer-related sexual dysfunction. However, none of the participants in the trial were younger than the age of 35, and young women were more likely to drop out of the study. This result underscores the need to develop an intervention that takes the preferences and needs of young persons with cancer into account, which was the rationale for building a comprehensive self-help program that included several key components of successful web-based interventions.

The Fertility and Sexuality Following Cancer (Fex-Can) Project

The present study is part of the Fertility and Sexuality Following Cancer (Fex-Can) research project, aiming at investigating and treating sexual problems and fertility distress among AYAs with cancer. The project is being conducted in several steps, including the development of a self-help web-based program in collaboration with a group of patient research partners [16] and the present evaluation of the program’s feasibility. Subsequent steps include a population-based cohort study of sexual problems and fertility distress in 16- to 40-year-old AYAs with cancer with an embedded randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing the effectiveness of the self-help web-based intervention (ISRCTN36621459).

The Fex-Can intervention

The Fex-Can intervention consists of two web-based programs, one targeting sexual problems and one targeting fertility distress. Both programs are organized in consecutive modules (eight for fertility and six for sexuality), delivered over a period of 2 months. For an overview of the content, see Table 1.

Each module targeted a specific aspect of sexuality or fertility after cancer and includes short articles (educational and behavior change content), exercises, photos, illustrations, and video vignettes with AYAs with cancer narrating their experiences with the topics discussed. The exercises in the sexuality program were aimed at increasing sexual pleasure and functioning, by targeting body awareness and acceptance, for example. Similarly, the exercises in the fertility program were aimed at helping users find new ways of handling their threatened or lost fertility by improving problem-solving skills, mindfulness, and acceptance, for example. The program also included an online-moderated discussion forum, where users could interact with other users, and an expert forum, where participants could post questions and receive tailored feedback from experts in different fields. In addition, the sexuality program offered telephone consultations at the beginning and end of the program. The combination of educational and behavior change content, multimedia, interactive online activities, and partial feedback support (key components defined by Barak [17]) was intended to increase the persuasiveness of the program and encourage users’ active participation. Much effort was devoted to make the intervention technically functional, esthetic, and easy to use. The intervention was created with a responsive design and therefore could be used on computers, tablets, and smartphones.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the feasibility of a self-help web-based intervention to alleviate sexual problems and fertility distress in adolescents and young adults with cancer.

Methods

Design

Feasibility studies are part of the development of complex interventions [18] with the aim to prepare for a full-scale RCT [19] and are particularly important for web-based interventions that commonly suffer from high dropout rates and non-usage [20, 21]. The present feasibility study evaluated the demand (how much the intervention was used), the acceptability (how well the intervention was accepted), the preliminary efficacy (preliminary indices of the intervention being effective), and the functionality (technical functionality and user-friendliness) of the intervention.

Participants

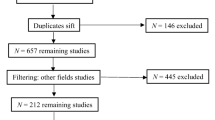

Participants were recruited through social media, newspapers, and notice boards at oncology and hematology clinics and patient organizations and through physicians and nurses in cancer care. We aimed at recruiting AYAs with cancer who were 16 to 40 years old, 1–5 years after diagnosis of selected cancers (breast, cervical, ovarian, testicular, central nervous system [CNS], or lymphoma), had self-reported sexual problems or fertility distress, were able to read and speak Swedish, and had access to an Internet connection.

In addition to the participants who tested the intervention, two members (male and female) of the Swedish organization Young Cancer for young persons with cancer (16–30 years of age) provided written and oral feedback on the content of the intervention. They received access to the sexuality and fertility programs but did not participate in the intervention.

Measures

Feasibility testing

Feasibility was evaluated regarding the following aspects: demand (use of the intervention), acceptability (the relevance and adequacy of the content, layout, and language), preliminary efficacy (perceived increase in knowledge and improved skills for handling sexual problems or fertility distress), and functionality (technical functioning, organization, and usability). Data were collected via the website system, telephone interviews, continuous online evaluations, and a post-intervention scale.

Website system data

Login and logout data, the number of modules completed, as well as use of the discussion and expert forums, were documented to evaluate the intervention demand and functionality.

Telephone interviews

Each participant was contacted for two semi-structured telephone interviews: a 10min midpoint interview 1 month after the start of the intervention, to evaluate use (demand) and functionality, and a 30–60min exit interview a week after the participants completed the program. The latter interview evaluated the program content (acceptability) and participants’ use and experiences of different program features (demand, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy), as well as participants’ experiences of the program structure and functionality. The midpoint interviews were documented by the interviewers, and the exit interviews were recorded and transcribed. The same research team member (either author MW or JS) conducted both interviews with individual participants.

Continuous online evaluations

At the end of each module, the participants were presented with online items (four close-ended questions and one open-ended comment box) regarding the relevance of the content of the module, whether the content had evoked sadness or distress (acceptability and preliminary efficacy), whether the information and language had an acceptable level of difficulty (acceptability), and use and experience of exercises (demand and acceptability).

Post-intervention evaluation

A study-specific scale with nine items was used to evaluate the relevance and adequacy of the content (acceptability), as well as increased knowledge and improved skills for handling sexual problems or fertility distress (preliminary efficacy). Responses were given on a 4-point Likert scale (“Completely agree,” “Partly agree,” “Partly disagree,” and “Completely disagree”). The scale items are presented in Fig. 1.

Baseline assessment

Participants responded to a baseline postal questionnaire that included validated standardized instruments and study-specific items. Sexual problems were assessed with the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sexual Function and Satisfaction (PROMIS Sex-FS) [22]. Fertility distress was assessed with the Reproductive Concerns After Cancer (RCAC) scale [23] with 18 items (scores 1–5) that form six subscales (mean subscale scores ≥4 indicate high levels of distress). The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of participants, as well as questions regarding received information, were measured with study-specific items.

Procedure

The feasibility testing of the web-based intervention lasted for 2 months (60 days for the sexuality program and 70 days for the fertility program), with a new module accessible every 10th day.

Information about the study was sent by post together with a baseline questionnaire that included validated standardized instruments and study-specific items. Participants received access to one of the programs after the participant had completed the informed consent form and the baseline questionnaire. Participants could receive only one of the programs (based on their preference). Personal login details were sent by e-mail together with information about how to use the intervention. E-mail reminders were sent out when new modules became accessible.

One month after the program started, all participants were contacted by text message with an invitation to participate in a short telephone interview regarding their use of the intervention and the intervention’s functionality.

At the end of the allotted time for completing the program (60 and 70 days for the sexuality program and the fertility program, respectively), the participants received a postal post-intervention questionnaire that included the same instruments as those at baseline and a study-specific scale to evaluate the content of the intervention and the participants’ perceived benefits of participating in terms of increased knowledge and skills. Participants were also invited to participate in an exit telephone interview.

Results

Participants

Twenty-three participants completed the baseline questionnaire and started the intervention: 9 (8 women, 1 man) in the fertility program and 14 (11 women, 3 men) in the sexuality program. The median age was 30 years (range 18–43), and the median time since diagnosis was 2 years. Two individuals older than 40 years were accepted for inclusion in the sexuality program. One third of the participants were still receiving cancer treatment. Of the nine who started the fertility program, all rated high levels of distress on at least one of the RCAC subscales. The subscales in which most participants rated high distress concerned fertility potential (n = 7), partner disclosure (n = 6), and health of future children (n = 6). Of the 14 participants who started the sexuality program, 11 had been sexually active the previous month, and all but one (who later dropped out of the study) reported some or severe sexual problems (decreased sexual interest, n = 10; vaginal dryness, n = 6; pain/discomfort, n = 6; orgasm problems, n = 5). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 2.

The results regarding the feasibility of the Fex-Can intervention are based on website system data, telephone interviews, continuous online evaluations, and the post-intervention scale. The post-intervention scale and most of the exit interviews were completed by the participants with a high level of activity (referred to as “committed users”), while the continuous online evaluations and the midpoint interviews were also completed by participants who were less active in the program.

Demand

Demand was evaluated with the website system data, as well as the continuous online evaluations and the telephone interviews. All 23 participants logged in at least once. Fifteen participants (9/14 in the sexuality program and 6/9 in the fertility program) completed four or more of the modules in the program and will hereafter be referred to as “committed users.” Reasons reported for not completing the program included lack of time, receiving other treatment, or not having problems in all the areas covered by the program.

Most of the committed users performed at least one exercise during the program. Based on the interview data, participants in the sexuality program appeared to appreciate and use the exercises to a large extent. In the fertility program, the exercises were highly appreciated by some but were generally used to a lesser extent, and some participants mentioned having already learned mindfulness and problem-solving skills during their cancer treatment. Those who had not attempted to use any of the exercises (both fertility and sexuality) reported that they presently did not perceive a need. Even those who did not use the exercises themselves were generally positive about the inclusion of the exercises in the program.

All of the committed users engaged in the discussion forum in some way; all read, and many posted something at least once. However, the overall activity in this forum was low. Most committed users also read and/or posted questions in the “ask the expert” forum.

Participants in the sexuality program were offered two telephone consultations as part of the intervention, one in the beginning and one at the end of the intervention. Three participants used the consultation option only in the beginning, and one used it in the beginning and the end of the program. These participants were satisfied with the counseling sessions. Reasons for not using this feature included not wanting to discuss such things over the phone or not understanding how to book a counseling session online.

Acceptability

Based on the results from the continuous online evaluations, telephone interviews, and the post-intervention scale (Fig. 1), the majority of the committed users in both programs thought the content was relevant, informative, and focused on important issues. Many expressed satisfaction with having such comprehensive information gathered in one place. The structure of the program, with a mix of articles, exercises, and short video vignettes in every module, was generally appreciated by the participants. In addition, the web-based format was well accepted. In the interviews, some participants emphasized that they had reduced concentration or energy but that the flexible format, in which they could choose when and how to use the program, enabled them to go through the intervention. They described reading a short section of a text and then taking a break before continuing or reading certain texts repeatedly. One participant had been hospitalized during the launch of some of the modules but had been able to catch up with the program later. In addition, a few busy participants with full schedules described going through the intervention in larger and smaller chunks, e.g., reading short sections on a smartphone while waiting for a bus.

Most participants thought the content was easy to understand, but some participants felt overwhelmed by too much information (Fig. 1). The interviews further revealed that this referred to perceiving some texts as too long, especially by participants with self-reported cognitive impairment or reading and writing difficulties.

Some participants spontaneously said they liked that the texts were written in an inclusive way, for example, without assumptions the reader was heterosexual or had a partner. One participant thought that there was too much focus on being in a relationship, and one participant pointed out that the fertility program lacked information suitable for homosexual men. Most of the participants liked the photos. Some said spontaneously the photos were nice and appropriate, although one participant thought there were too many couples in the photos. In addition, the illustrations (i.e., anatomical pictures) were generally appreciated among those who commented on them.

The video vignettes were appreciated by the majority of the participants (Fig. 1). Participants saw the videos as a nice break from the more informative texts and liked that the videos starred real persons with real stories to which the participants could relate. Some mentioned the lack of videos that included men. A few participants mentioned that they themselves had a need for medical facts rather than videos with others’ stories, but it was good to have a mixture of content to meet diverse needs among users. The exercises and forums were appreciated by most of the participants, although the activity varied. However, the answers in the ask the expert forum were perceived by some as too general, due to the experts’ lack of specific knowledge regarding the questioner’s medical history, current or previous medication, etc. As for the discussion forum, the opportunity to connect with others in the same situation was appreciated. The moderation of the discussion forum and the anonymity were pointed out as important features.

Preliminary efficacy

Results from the continuous online evaluations, telephone interviews, and the post-intervention scale (Fig. 1) indicated the preliminary efficacy of the intervention. The majority of the 15 participants who completed the post-intervention scale thought they had received information that helped them handle their sexual problems or fertility distress, as well as emotional problems, to some extent or completely (Fig. 1). Most participants also agreed or partially agreed with the statement “the intervention helped me to see different solutions to my problem”. However, a few participants described a temporary increase in distress or sadness at some point during their participation in the program (continuous online evaluations and interviews). This experience was described as unavoidable when learning and thinking about common problems related to sexuality or fertility following cancer. Some participants experienced that their increased knowledge in total led to personal growth or increased strength (e.g., feeling more self-confident).

Functionality

Functionality was evaluated with the website system data and telephone interviews. The intervention generally functioned well technically and was used on computers, tablets, and smartphones. The website was described as “professional” in its design and functioning, except for unsatisfactory sound quality on some of the videos. In addition, one participant pointed out that the text lines had more letters than what is recommended on websites. Most of the participants thought the program was easy to use after having tested it for the first time. Some described initial uncertainties about the website structure or the consecutive opening of articles. There were some minor technical problems: temporary login or logout problems, difficulties finding the forums, problems watching or hearing the videos, and problems related to e-mail distribution or content. When technical problems occurred, participants and researchers communicated through e-mail. Support was provided within 24 h.

The division of the intervention into modules, launched every 10th day, was appreciated by most participants. Two participants preferred 14 days between the launch of new modules, and another two preferred that all the material had been available from the beginning. Some mentioned realizing the advantages of working with consecutive modules after a while. Other ideas for improvement included links to the program in the automatic e-mails, addition of a search function for the website, and notifications for new postings in the forums.

Discussion

Overall, the study results indicate that the Fex-Can intervention was feasible for AYAs with cancer, regarding demand, acceptability, preliminary efficacy, and functionality. Many participants in the sexuality and fertility programs expressed satisfaction with the intervention as a whole. The participants who went through more than four modules in the program—the committed users—often went through the whole program and used most of its features. The information, the mix of texts, videos, and exercises, the flexibility regarding how and when to use the program, and the opportunity to interact with others in the same situation were features that were generally appreciated. Most participants were also satisfied with the language and the tone of the texts, as well as the general organization of the intervention. We originally developed the intervention in close collaboration with other AYAs with cancer, which might have contributed to making the intervention feasible for this patient group [16].

Generally, the participants’ opinions did not differ between the sexuality and fertility programs. However, use and appreciation of the exercises diverged between the programs. Motivation to use the exercises might have been higher in the sexuality program due to expectations of improvement in sexual function. The exercises in the fertility program aimed at managing a situation of threatened or lost fertility and may have seemed more demanding and less attractive. As most of the participants were still generally positive about the inclusion of the exercises in the program, they will be kept unchanged for the future RCT.

Despite some technical problems and low activity, the discussion forum was appreciated by the participants who used it, and the feature will be kept for the future RCT. However, the design will be revised to improve the forum’s visibility on the site, and notifications for new postings will be added.

Regarding the ask the expert forum, most participants used this function to some extent, and many posed their own questions. However, the relatively high amount of work behind this feature for the research group and external experts did not match the outcome for the participants. The nature of the questions asked also indicated that the participants already had satisfactory contact with their physicians in charge and posed questions to get a second opinion. Therefore, this feature will not be retained for the larger RCT.

The present study has strengths, as well as limitations. In this feasibility study of a comprehensive program, 15 of the 23 participants remained active throughout the whole intervention (2 months). The study had a limited representation of men (4 out of 23), but in other aspects, the participants appeared well matched to the future target group, representing different ages, diagnoses, and treatments, and all expressing sexual problems or fertility-related distress. Due to the small number of participants in each program, scores for sexual function and fertility distress were reported only at the group level to ensure confidentiality. Although sexuality and fertility are considered important issues among AYAs with cancer [9, 10], it was not easy to recruit participants for the study. This might be due to the sensitive nature of the topic and the recruitment strategy, as those who were willing to participate had to actively contact the researchers on their own initiative. The low number of men in our study is in line with previous reports of low representation of men in survey studies concerning health issues [24] and men’s reluctance to seek help for both medical and psychological health problems [25, 26]. However, while the demand for the intervention appeared to be lower among male patients, there were no indications that the intervention was less feasible for men. As for the results, a general methodological consideration is that participants may have had difficulty expressing negative opinions in the interviews. Participants who remained throughout the intervention and participated in the exit interviews shared positive and negative experiences of using the program, and the opinions expressed in the interviews were in line with the results from the post-intervention questionnaires. However, it is possible that some negative experiences were not expressed and that those participants who did not complete the program or participate in the evaluations had different views.

In conclusion, the present study indicated that this web-based intervention was feasible for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Considering the fact that men constituted a minority of the study participants and committed users, our conclusions about the feasibility of the intervention for male patients are limited. Based on these findings, the effectiveness of the intervention to decrease sexual problems and fertility distress will be tested in a population-based RCT for AYAs with cancer. To the extent that the intervention proves to be effective, this program could be implemented in the regular care of AYAs with cancer in Sweden as the web-based format is cost-effective irrespective of geographic distance. Another clinical implication could be to give health care providers in cancer care access to parts of the program to increase the providers’ competence in these issues.

References

Rodriguez-Wallberg KA (2012) Principles of cancer treatment: impact on reproduction. Adv Exp Med Biol 732:1–8

Wettergren L, et al. (2016) Cancer negatively impacts on sexual function in adolescents and young adults: the AYA Hope study. Psychooncology

Sanchez Varela V, Zhou ES, Bober SL (2013) Management of sexual problems in cancer patients and survivors. Curr Probl Cancer 37(6):319–352

Arden-Close E, Eiser C, Pacey A (2011) Sexual functioning in male survivors of lymphoma: a systematic review (CME). J Sex Med 8(7):1833–1841

Fobair P et al (2006) Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 15(7):579–594

Madanat LM et al (2008) Probability of parenthood after early onset cancer: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 123(12):2891–2898

Tang SW et al (2016) Birth rates among male cancer survivors and mortality rates among their offspring: a population-based study from Sweden. BMC Cancer 16:196

Gorman JR et al (2015) Experiencing reproductive concerns as a female cancer survivor is associated with depression. Cancer 121(6):935–942

Bibby H et al (2017) What are the unmet needs and care experiences of adolescents and young adults with cancer? A systematic review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 6(1):6–30

Flynn KE et al (2012) Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psychooncology 21(6):594–601

Armuand GM et al (2012) Sex differences in fertility-related information received by young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 30(17):2147–2153

Pingree S et al (2010) The value of theory for enhancing and understanding e-health interventions. Am J Prev Med 38(1):103–109

Richter D et al (2015) Psychosocial interventions for adolescents and young adult cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 95(3):370–386

Meneses K et al (2010) Evaluation of the Fertility and Cancer Project (FCP) among young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 19(10):1112–1115

Schover LR et al (2013) Efficacy trial of an Internet-based intervention for cancer-related female sexual dysfunction. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 11(11):1389–1397

Winterling J et al (2016) Development of a self-help web-based intervention targeting young cancer patients with sexual problems and fertility distress in collaboration with patient research partners. JMIR Res Protoc 5(2):e60

Barak A, Klein B, Proudfoot JG (2009) Defining Internet-supported therapeutic interventions. Ann Behav Med 38(1):4–17

Abbott JH (2014) The distinction between randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and preliminary feasibility and pilot studies: what they are and are not. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 44(8):555–558

Bowen DJ et al (2009) How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med 36(5):452–457

van Bruinessen IR et al (2014) Active patient participation in the development of an online intervention. JMIR Res Protoc 3(4):e59

van Gemert-Pijnen JE et al (2011) A holistic framework to improve the uptake and impact of eHealth technologies. J Med Internet Res 13(4):e111

Weinfurt KP et al (2015) Development and initial validation of the PROMIS((R)) sexual function and satisfaction measures version 2.0. J Sex Med 12(9):1961–1974

Gorman JR et al (2014) A multidimensional scale to measure the reproductive concerns of young adult female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 8(2):218–228

Mindell JS et al (2015) Sample selection, recruitment and participation rates in health examination surveys in Europe—experience from seven national surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 15:78

O'Brien R, Hunt K, Hart G (2005) “It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate”: men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Soc Sci Med 61(3):503–516

Sullivan L, Camic PM, Brown JS (2015) Masculinity, alexithymia, and fear of intimacy as predictors of UK men's attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help. Br J Health Psychol 20(1):194–211

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Doctoral School in Health Care Sciences at Karolinska Institutet, the Cancer Research Foundations of Radiumhemmet (121242), the Swedish Cancer Society (2010/877), the Vårdal Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (ethical approval) and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiklander, M., Strandquist, J., Obol, C.M. et al. Feasibility of a self-help web-based intervention targeting young cancer patients with sexual problems and fertility distress. Support Care Cancer 25, 3675–3682 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3793-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3793-6