Abstract

The human anterior insula is anatomically and functionally heterogeneous, containing key nodes within distributed speech–language and viscero-autonomic/social–emotional networks. The frontotemporal dementias selectively target these large-scale systems, leading to at least three distinct clinical syndromes. Examining these disorders, researchers have begun to dissect functions which rely on specific insular nodes and networks. In the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia, early-stage frontoinsular degeneration begets progressive “Salience Network” breakdown that leaves patients unable to model the emotional impact of their own actions or inactions. Ongoing studies seek to clarify local microcircuit- and cellular-level factors that confer selective frontoinsular vulnerability. The search for frontotemporal dementia treatments will depend on a rich understanding of insular biology and could help clarify specialized human language, social, and emotional functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

How critical is the anterior insula to our most valued social, emotional, and cognitive functions? Clinical neuroscience has begun to provide insights into this question, and no neurological disease has become more relevant than frontotemporal dementia (FTD). FTD refers to a family of clinical syndromes caused by underlying frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) pathology (reviewed in Seeley 2008). The major FTD clinical subtypes include a behavioral variant (bvFTD), semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA), which typically begin in the sixth decade of life. As detailed in subsequent sections and in Table 1, bvFTD is associated with dramatic changes in social–emotional processing which result from targeted medial frontal and frontoinsular degeneration. Semantic dementia presents with early disintegration of word, object, person-specific, and emotional meaning (Hodges et al. 1994; Seeley et al. 2005) followed by striking behavioral changes akin to bvFTD (Kertesz et al. 2005; Seeley et al. 2005; Snowden et al. 2001). The accompanying anatomical pattern begins in the temporal pole and amygdala before spreading to subgenual cingulate, frontoinsular, ventral striatal, and upstream posterior temporal regions (Brambati et al. 2007a). PNFA is associated with effortful, nonfluent, often agrammatic speech, at times accompanied by speech apraxia or dysarthria, and largely spares behavior. This symptom complex reflects dominant frontal operculum and dorsal anterior insula injury (Gorno-Tempini et al. 2004; Josephs et al. 2006; Nestor et al. 2003). Any of these syndromes, but most often bvFTD, may be accompanied by motor neuron disease, which truncates an already rapid and lethal disease course (Roberson et al. 2005).

At autopsy, FTLD features synaptic degeneration, gliosis, and neuronal loss (Brun et al. 1995), with subtypes defined by neuronal and glial disease protein aggregates that may contain either tau (FTLD-tau), the TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43, FTLD-TDP), or the newly identified FTLD disease protein, fused in sarcoma (FUS, FTLD-FUS) (Mackenzie et al. 2010). In health, tau is localized to the axon and stabilizes microtubles, facilitating axonal transport (Ebneth et al. 1998). Although both TDP-43 and FUS are nuclear DNA/RNA binding proteins, TDP-43 regulates transcription within the nucleus through its impact on exon splicing (Ayala et al. 2005), whereas FUS appears to help target-specific mRNAs to dendritic spines where they participate in activity-dependent spine remodeling (Fujii et al. 2005). Although most FTD occurs in the absence of a known genetic mutation, each FTD clinical syndrome bears a different relationship to the FTLD genetic and molecular subtypes (Table 1). It should be noted, however, that these associations remain a topic of vigorous investigation and debate (Hodges et al. 2004; Mesulam et al. 2008).

Clarifying insular biology and function will accelerate FTD research, bringing patients closer to treatments and cures. At the same time, FTD-related focal degenerations provide unique lesion models for understanding the insula and carry the potential to delineate network-, layer-, and even cell type-specific contributions to insular function. These approaches could, in turn, elucidate key aspects of other common neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, anxiety states, autism, eating disorders, and substance abuse (to name a few) whose pathophysiologies seem embedded within the insula and its core network affiliates (Di Martino et al. 2009; Fornito et al. 2009; Naqvi and Bechara 2009; Rotge et al. 2008; Schienle et al. 2009; Uddin and Menon 2009).

Anatomical considerations

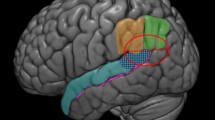

Understanding FTD-related insula degeneration requires a modern functional–anatomical framework. Using cytoarchitectonic approaches, the anterior insula can be divided into no less than two but more likely several distinct subregions (Mesulam and Mufson 1982a; Rose 1928; von Economo and Kosinkas 1925) (Butti and Hof 2010; Kurth et al. 2010). The two major subdivisions prove most relevant to understanding FTD. First, at the basal transition from orbitofrontal cortex to insula stretches the frontoinsular cortex [Area Frontoinsulare, or “FI” of von Economo (von Economo and Kosinkas 1925)], a ventral agranular region distinguished in humans, apes, most cetaceans, and elephants by large, conspicuous, Layer 5 bipolar neurons called von Economo neurons (VENs) also found in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Allman et al. 2010) (Hakeem et al. 2009; Hof and Van der Gucht 2007; Nimchinsky et al. 1999; von Economo 1926). Second, dorsal to the major lateral convexity of the anterior insula, a dorsal dysgranular region extends toward the frontal operculum. Here, VENs quickly transition from rare to absent. More posteriorly, but anterior to the central insular sulcus, the dorsal dysgranular insula continues beneath the frontal operculum (Mesulam and Mufson 1982a). These subregions feature distinct connectivity patterns in monkeys (An et al. 1998; Mesulam and Mufson 1982b) as well as in humans, as revealed by recent functional (Taylor et al. 2009) and structural (Nanetti et al. 2009) connectivity approaches to insular parcellation (Fig. 1a). In monkeys, the ventral agranular insula connections ally preferentially with temporal pole, limbic, and brainstem regions (An et al. 1998; Mesulam and Mufson 1982b), whereas the dorsal dysgranular anterior insula bears unique axonal connections to frontal opercular and ventrolateral frontal regions.

Functional–anatomical background for understanding insula degeneration in FTD (a) Nanetti and colleagues used a data-driven, k-means clustering approach, applied to diffusion-weighted structural connectivity imaging data to decompose the insula into 3–4 distinct subregions, including dorsal and ventral anterior insula. Figure adapted with permission from (Nanetti et al. 2009). b–c These anterior subregions feature distinct functional affiliations, as demonstrated by Mutschler et al. in a large-scale meta-analysis of functional imaging studies. These authors linked the dorsal anterior insula to speech and language functions (b). The ventral anterior insula (c), in contrast, was activated by autonomic/interoceptive tasks, and subregions (inset) showed amygdalar co-activation during social–emotional processing. Figure adapted, with permission, from (Mutschler et al. 2009)

Not surprisingly, insular subregion functions reflect the distinctive connectional associations outlined above. In humans, the ventral agranular frontoinsula responds to diverse viscero–autonomic–nociceptive challenges and co-activates with the amygdala and pregenual ACC during scores of social–emotional paradigms (Fig. 1b) (Critchley 2005; Kurth et al. 2010; Mutschler et al. 2009; Singer et al. 2009). The dominant dorsal anterior insula, in contrast, activates in response to speech and language fluency tasks (Mutschler et al. 2009) and lesions in the nearby dorsal mid-insula produce speech apraxia (Ackermann and Riecker 2004; Dronkers 1996). Although functions of the non-dominant dorsal anterior insula–frontal opercular network remain uncertain, existing data suggest a possible role in response suppression and task switching and maintenance functions (Aron et al. 2004; Dosenbach et al. 2006). These cytoarchitectonic, connectional, and functional profiles provide a foundation for understanding FTD behavioral and language syndromes.

The emerging link between the insula and FTD

For decades, the insula lingered in obscurity to most FTD researchers, just as it evaded the attention of many studying social, emotional, and behavioral function. But the potential significance of the insula was noted by many of the pioneer functional anatomists (Mesulam and Mufson 1982a; Mesulam and Mufson 1982b; Nauta 1971; Penfield and Faulk 1955; Rose 1928; von Economo 1926), whose writings anticipated more recent models of the anterior insula as a central hub within human emotional awareness and behavioral guidance networks (Craig 2009; Damasio 1999). Likewise, groundbreaking FTLD pathological studies by Brun and coworkers noted significant, if topologically heterogeneous involvement of the anterior insula and its paralimbic counterpart, the ACC (Brun and Gustafson 1978).

Defining a comprehensive FTD topography in autopsy materials, however, proved laborious and few studies could capture early-stage disease. Based primarily on patients with bvFTD, Broe et al. (2003) clustered postmortem brains into very mild (Stage 1), mild (Stage 2), moderate (Stage 3), and severe (Stage 4) cases and found that Stage 1 showed atrophy limited to dorsomedial frontal cortex (including ACC) and posterior orbitofrontal cortex where it meets the frontoinsula. These seminal observations were reinforced by a transition from region-of-interest based volumetric neuroimaging to unbiased, whole-brain, statistical parametric mapping techniques. A host of studies came forth, using voxel-based morphometric (Boccardi et al. 2005; Rosen et al. 2002), cortical thickness (Richards et al. 2009), perfusion (Varrone et al. 2002), metabolic (Ibach et al. 2004), and neurochemical (Franceschi et al. 2005) imaging to identify anterior insula and ACC (both pre- and sub-genual parts), along with ventral striatum, medial thalamus, and frontopolar cortex, as the most consistent targets in bvFTD (Schroeter et al. 2006) and shared targets in bvFTD and SD (Rosen et al. 2002).

The diversity of FTD-related insula involvement has also been newly appreciated, as researchers now more rigorously separate patients according to clinical syndrome. These studies have revealed that bvFTD involves both ventral and dorsal anterior insula by the time of early clinical presentation (Seeley et al. 2008; Fig. 3), especially on the non-dominant side. The first-affected insular subregion in bvFTD has yet to be resolved. Semantic dementia begins as a left or right temporal pole disease but spreads preferentially to ventral anterior insula (Pereira et al. 2009; Rohrer et al. 2009), whereas in PNFA the dominant dorsal anterior insula receives the brunt of the injury (Gorno-Tempini et al. 2004; Nestor et al. 2003; Rohrer et al. 2009). Moreover, anterior insula involvement stands out whether the patient’s FTD syndrome is due to underlying FTLD-tau or FTLD-TDP (Pereira et al. 2009; Whitwell et al. 2005). Efforts to use antemortem imaging to differentiate pathological FTLD from Alzheimer’s disease have also emphasized the anterior insula, ACC, and ventral striatum as the sole regions to show significantly greater MR atrophy among those later diagnosed with FTLD at autopsy (Rabinovici et al. 2007).

More recently, disease-oriented neuroimaging research has moved toward more dynamic assessments of network connectivity, confirming an idea that has long been suspected: that each focal neurodegenerative syndrome targets a specific large-scale distributed network. Evidence supporting this hypothesis for FTD came from an experiment in which Seeley et al. (2009) profiled the atrophy patterns in five neurodegenerative syndromes and compared these patterns to normal networks defined in healthy controls with intrinsic connectivity network or “resting-state” fMRI and structural covariance analyses. Intrinsic connectivity networks reflect temporally coherent fMRI signal fluctuations within subjects, whereas structural covariance networks emerge from correlating regional gray matter volumes across large groups of healthy individuals. The results showed that bvFTD, semantic dementia, and PNFA each produce an atrophy pattern that mirrors a distinct healthy brain network, and these networks, in turn, feature contrasting links to the anterior insula, as described above and predicted by the known primate insular connectivity patterns.

Early-stage frontoinsular degeneration in bvFTD: an update

The remaining sections focus primarily on bvFTD, whose investigation seems poised to provide an unprecedented window into the anatomical underpinnings of specialized human social–emotional capacities.

Clinical features

The full-blown bvFTD syndrome includes poor judgment, loss of initiative, deficient self-control (at times with overeating or substance abuse), compulsive rituals or stereotypies, and a profound loss of interpersonal warmth, caring, tact, and empathy (Miller et al. 1993; Snowden et al. 2001). The earliest symptoms, however, are subtle and may be mistaken for psychiatric illness or a “mid-life crisis”. One mother with preclinical bvFTD seemed unbothered when her adolescent son fled home for 3 days after an argument. A salesman could not anticipate that his client (a single mother at home with young children) would become afraid and then outraged by his repeated knocks on her door at 10:00 p.m. on a Tuesday. A third patient was hospitalized for severe dehydration after wearing a down parka outdoors on a hot summer day. Though anecdotal, these scenarios and countless others like them suggest that during incipient bvFTD the brain can no longer (1) represent the personal significance of ambient (internal or external) conditions or (2) use these representations to guide behavior. Often loved ones demand medical evaluation only after patients have been overlooked for expected promotions, lost or changed jobs, spent excessive sums on frivolities or solicitations, or have entered couples’ counseling for marital disinterest or infidelity. Encouragingly, a growing body of well-designed experiments, rooted in the modern methods of behavioral neuroscience (see below), has begun to isolate and characterize the specific social and emotional functions lost in early bvFTD, many of which remain spared in Alzheimer’s disease (Seeley et al. 2007a).

Regional and network features

BvFTD was once viewed as a diffuse frontotemporal disorder, perhaps due to the impressive but misleading textbook images of late-stage, postmortem gross brain specimens, which too often taught researchers that bvFTD destroys the entire rostral forebrain. This misconception can now be discarded thanks to overwhelming evidence that bvFTD represents a specific neural system disease (Boccardi et al. 2005; Schroeter et al. 2006; Seeley et al. 2008, 2009). In the mildest clinical phases, atrophy can be seen within the anterior insula (dorsal and ventral, especially on the right), ACC, and a network of subcortical and thalamic regions (Fig. 2) (Seeley et al. 2008). As intimated above, the atrophy pattern features remarkable spatial similarity to a large-scale distributed human brain network anchored by the right frontal insula, which Seeley et al. described using intrinsic functional connectivity mapping in healthy controls and have referred to as the “Salience Network” for its role in processing diverse homeostatically relevant internal or external stimuli (Seeley et al. 2007b, 2009). With advancing clinical severity, bvFTD atrophy spreads throughout this Salience Network and into neighboring supervisory executive-control (Fig. 2) (Brambati et al. 2007b; Seeley et al. 2008) and possibly temporopolar emotional–semantic systems in some patients (Whitwell et al. 2009a). BvFTD anatomical heterogeneity (Whitwell et al. 2009b) may help to further dissociate subsystems within this Salience Network, but this possibility has yet to be explored with network-based imaging methods. Intriguingly, Salience Network regions show striking volume loss in schizophrenia (Fornito et al. 2009), in which patients exhibit abnormal right anterior insula/ventrolateral prefrontal cortex responses to stimulus salience (Walter et al. 2009).

Stage-specific atrophy patterns in bvFTD. Fifteen patients with bvFTD were identified as having very mild (CDR = 0.5), mild (CDR = 1), or moderate to severe (CDR > 2) functional impairment. Voxel-based morphometry comparisons between each severity group and healthy controls revealed early-stage atrophy most notable in the pregenual ACC (pACC) and anterior insula, including the frontoinsular (FI) and dorsal anterior (dAI) subregions featured in Fig. 1. Striatal, thalamic, and frontopolar (FP) nodes were also affected. Data adapted, with permission, from (Seeley et al. 2008)

How does the bvFTD Salience Network injury take hold? What factors “bring” the disease to this system, and where does the disease process exert its greatest effects on network connectivity? Recently, Zhou and colleagues charted Salience Network connectivity disruptions in bvFTD (Zhou et al. 2010), using the same intrinsic connectivity mapping techniques used to define this network in healthy individuals (Beckmann et al. 2005; Seeley et al. 2007b, 2009). The analysis revealed significant connectivity reductions between the overall network and its anterior insular, cingulate, striato–pallido–thalamic, limbic, and brainstem nodes (Fig. 3a), including the amygdala, periaqueductal gray, and parabrachial nucleus, a known autonomic relay between spinal cord and thalamus (Saper and Loewy 1980). Strikingly, bvFTD clinical severity correlated with connectivity disruption in only one Salience Network region: the right frontoinsula (Fig. 3b). This intimate link between right frontoinsular connectivity and disease severity may suggest that this region acts as a critical Salience Network “hub”, which, when injured, de-stabilizes network synchrony (Palop et al. 2006), disrupts network-based neurotrophic mechanisms (Salehi et al. 2003), or seeds the transneuronal spread of misfolded disease protein throughout the distributed neural system with which the right frontoinsula communicates (Frost and Diamond 2009).

Salience Network connectivity disruption in bvFTD. a Twelve patients with mild bvFTD (mean CDR = 1.0) showed intrinsic connectivity reductions compared to age-matched healthy control subjects in distributed Salience Network nodes, including the frontoinsula (FI), lateral orbitofrontal cortex (lOFC), dorsal anterior insula (dAI), midcingulate cortex (MCC), ventral striatum (VStr), basolateral amygdala (blAmy), thalamus, substantial nigra/ventral tegmental area (SN/VTA), periaqueductal gray (PAG), and dorsal pons and parabrachial nuclei (PBN). b Of these regions, however, only the right FI correlated with functional severity, as measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, sum of boxes score. Data from Zhou et al. (2010), adapted with permission from Oxford University Press

Microanatomical features

But a specific molecular, cellular, or microcircuit signature must exist within the Salience Network that confers selective vulnerability to this system in bvFTD. Noting the unique presence of VENs in ACC and the frontoinsula, Seeley et al. hypothesized that these specialized neurons might confer selective vulnerability due to some as yet unknown but distinctive biological feature. To test this notion, these investigators quantified left ACC VENs, correcting for neighboring neuron loss, and found VENs 69% reduced in bvFTD compared with controls (Seeley et al. 2006). Patients with Alzheimer’s disease, in contrast, showed no selective VEN vulnerability. But scant published data exist on whether and how early bvFTD targets frontoinsular VENs (Seeley et al. 2007a) or whether loss of these neurons may correlate with core bvFTD symptoms. Future studies should seek to fill these gaps, build a detailed spatiotemporal model of VEN degeneration in the context of overall bvFTD anatomical progression, and quantify relationships between neuronal vulnerability and specific subcellular pathogenic events, such as disease protein misfolding, mislocalization, hyperphosphorylation, and aggregation (Fig. 4). Furthermore, molecular-genetic and physiological studies may provide insights into which distinctive VEN biological feature confers accentuated vulnerability in bvFTD.

Frontoinsular VEN degeneration in bvFTD. This patient with early-stage bvFTD died of motor neuron disease and showed frequent TDP-43 neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in frontoinsular von Economo neurons. Here, a cluster of dysmorphic right FI VENs (arrowheads) shows TDP-43 redistribution from the nucleus to speckled cytoplasmic inclusions. A neighboring VEN (arrow) exemplifies a more normal morphology, and surrounding layer 5 pyramidal neurons show normal nuclear TDP-43 localization. TDP-43 immunohistochemistry with hematoxylin counterstain. Scale bar 20 µm. Immunohistochemistry courtesy S. Gaus

FTD as a model for understanding anterior insula contributions to speech, language, and social–emotional functions

Complex language-related functions lost in PNFA and semantic dementia have now been carefully disentangled using elegant language assessment tools, developed through decades of aphasia research on patients with vascular or other focal brain lesions. For example, consistent with a finding from the stroke literature (Dronkers 1996), patients with PNFA and apraxia of speech show focal dorsal anterior-to-middle insula/frontal opercular dysfunction (Nestor et al. 2003). Semantic dementia has provided the major disease model linking the temporal poles to domain-general semantic knowledge (Hodges et al. 2000) and has helped to reveal distinct temporal lobe subregion contributions to category-specific semantic processing (Brambati et al. 2006). Historically, the “social brain” assessment toolbox has remained much less well-developed, leaving researchers with limited means to define the functions lost in bvFTD. Exciting recent studies, however, have begun to implement controlled laboratory-based experiments and validated social neuroscientific instruments to outline the early bvFTD social–emotional deficit profile.

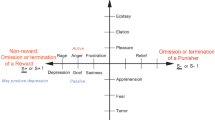

Considering the anatomical focality of early bvFTD, we should expect that early bvFTD functional deficits might exhibit commensurate selectivity within the broad social–emotional function spectrum. Recent work by Levenson and coworkers underscores this principle and has begun to create a list of candidate functions for which the frontoinsula and its unique cellular constituents might prove critical. Most interestingly, bvFTD does not take away all autonomic and emotional functions. For example, peripheral autonomic responses to asocial stressors, such as handgrip and startle, persist in early bvFTD (Sturm et al. 2006, 2008), perhaps because these responses rely on brainstem central pattern generators (Saper 2002). Even basic autonomic and facial affective responses to emotional film stimuli endure in controlled laboratory settings despite symptoms that might seem to suggest otherwise (Werner et al. 2007). Breakdowns in emotional processing become overt, however, when the stimulus-context milieu requires self-referential social processing. So not startle itself, but the embarrassment that results from the startle response, is abolished in bvFTD (Sturm et al. 2006). Not singing karaoke, but watching one’s self singing karaoke on videotape (before an audience) reveals patients’ blunted autonomic and behavioral responses (Sturm et al. 2008). Perhaps for analogous reasons, selected patients with bvFTD have been shown to keep eating, compulsively, despite reporting satiety (Woolley et al. 2007). In this experiment, the sandwich volume patients consumed (given unrestricted access) correlated inversely with right frontoinsular and striatal volume (Fig. 5). This finding may suggest that it is not the interoceptive satiety signals themselves [which may rely on posterior insular cortex (Wang et al. 2008)] but the emotional–behavioral impact (salience) of those signals that is disrupted by right frontoinsular damage. In this way, overeating patients with bvFTD may lack the unpleasantness of feeling overly full, which no longer prevents them from picking up the next sandwich. Whether this “evaluative interoception” deficit begins as domain-specific (social salience only, for example) or more domain-general (social, olfactory–gustatory, viscero-autonomic, and nociceptive salience) remains uncertain, but careful lesion–deficit correlations in bvFTD may help to clarify how the anterior insula organizes its role in monitoring all aspects of the internal milieu.

Right frontoinsular damage associated with binge eating. In this laboratory-based experiment, right frontoinsular atrophy (a) correlated with the number of quarter sandwiches consumed by patients when given unrestricted food access (b). Adapted from data reported in (Woolley et al. 2007)

In related social neuroscience experiments from other groups, patients with bvFTD have shown profound deficits in empathy (Lough et al. 2006; Rankin et al. 2006) and interpersonal warmth (Sollberger et al. 2009), both specifically linked to right frontoinsular and temporopolar degeneration. Related capacities, including theory of mind (Eslinger et al. 2005) and social conceptual knowledge (Zahn et al. 2009) have further shown deficits in bvFTD. Mendez and colleagues have shown that bvFTD undermines emotional aspects of morality despite sparing cognitive moral reasoning (Mendez et al. 2005; Mendez and Shapira 2009), suggesting that a core unifying deficit in bvFTD may be capacity to feel or care about the social impact of one’s own behavior. Considering the unique phylogeny of the VENs (Allman et al. 2010), it is worth noting that some authors view the functions lost in bvFTD as the unique province of large-brained, highly social mammals (Dunbar and Shultz 2007; Gallup 1982). In light of this view, it seems reasonable to question whether and how VENs enhance the human Salience Network in a way that facilitates or augments social–emotional functioning in our highly social species (Seeley 2008).

This review has focused on bvFTD deficits with potential links to the anterior insula. This emphasis has not been intended to suggest, however, that the anterior insula provides the modular neural instantiation of all complex social–emotional functions disrupted in bvFTD. As emphasized in previous sections, bvFTD targets a distributed large-scale Salience Network before spreading into related dorsolateral prefrontal executive-control or temporopolar emotional–semantic networks. Within the Salience Network, dynamic interactions between the frontoinsula and medial cingulofrontal, frontopolar, orbitofrontal, striatal, and other subcortical sites no doubt prove critical for the functions lost in bvFTD, and damage to any of these extra-insular regions (whatever the cause) may give rise to a subset of the same behaviors associated with frontoinsular damage. For example, right frontoinsular injury may produce disadvantageous social behaviors by degrading interoceptive guidance cues, but similar disinhibited behaviors may result from lesions to medial or lateral orbitofrontal regions (or to their striatal projection targets) if these lesions disrupt critical reward or response suppression mechanisms (Kringelbach and Rolls 2004; Rosen et al. 2005). Furthermore, faulty network–network interactions could explain important facets of the bvFTD profile, especially since one function of the right frontoinsula may be to initiate organized switching between large-scale distributed networks (Sridharan et al. 2008).

Pathways toward new discoveries

The search for FTD treatments, and even the treatments themselves, could bring new insights into the anterior insula’s role in human social–emotional processing. Until a disease-arresting therapy is identified, increasingly sophisticated human neuroimaging and postmortem studies could begin to forge links between specific networks, regions, layers, and cell types, on the one hand, and well-defined clinical deficits on the other. But the pace of discovery in basic FTD research is hastening, and one can now begin to imagine a more uplifting set of experiments. Some day, we will learn spectacular new lessons about human speech, language, and social–emotional functions by documenting our patients’ treatment-related recoveries.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Anterior cingulate cortex

- FTD:

-

Frontotemporal dementia

- FTLD:

-

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- FTLD-TDP:

-

FTLD with TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa inclusions

- FTLD-FUS:

-

FTLD with fused in sarcoma inclusions

- PNFA:

-

Progressive nonfluent aphasia

- VEN:

-

von Economo neuron

References

Ackermann H, Riecker A (2004) The contribution of the insula to motor aspects of speech production: a review and a hypothesis. Brain Lang 89(2):320–328

Allman JM, Tetreault NA, Hakeem AY, Manaye KF, Semendeferi K, Erwin JM, Park S, Goubert V, Hof PR (2010) The von Economo neurons in frontoinsular and anterior cingulate cortex in great apes and humans. Brain Struc Func 214(5–6). doi:10.1007/s00429-010-0254-0 (this issue)

An X, Bandler R, Ongur D, Price JL (1998) Prefrontal cortical projections to longitudinal columns in the midbrain periaqueductal gray in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol 401(4):455–479

Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA (2004) Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 8(4):170–177

Ayala YM, Pantano S, D’Ambrogio A, Buratti E, Brindisi A, Marchetti C, Romano M, Baralle FE (2005) Human, Drosophila, and C. elegans TDP43: nucleic acid binding properties and splicing regulatory function. J Mol Biol 348(3):575–588

Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, Smith SM (2005) Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360(1457):1001–1013

Boccardi M, Sabattoli F, Laakso MP, Testa C, Rossi R, Beltramello A, Soininen H, Frisoni GB (2005) Frontotemporal dementia as a neural system disease. Neurobiol Aging 26(1):37–44

Brambati SM, Myers D, Wilson A, Rankin KP, Allison SC, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML (2006) The anatomy of category-specific object naming in neurodegenerative diseases. J Cogn Neurosci 18(10):1644–1653

Brambati SM, Rankin KP, Narvid J, Seeley WW, Dean D, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Ashburner J, Gorno-Tempini ML (2007a) Atrophy progression in semantic dementia with asymmetric temporal involvement: a tensor-based morphometry study. Neurobiol Aging

Brambati SM, Renda NC, Rankin KP, Rosen HJ, Seeley WW, Ashburner J, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML (2007b) A tensor based morphometry study of longitudinal gray matter contraction in FTD. Neuroimage 35(3):998–1003

Broe M, Hodges JR, Schofield E, Shepherd CE, Kril JJ, Halliday GM (2003) Staging disease severity in pathologically confirmed cases of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 60(6):1005–1011

Brun A, Gustafson L (1978) Limbic lobe involvement in presenile dementia. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 226(2):79–93

Brun A, Liu X, Erikson C (1995) Synapse loss and gliosis in the molecular layer of the cerebral cortex in Alzheimer’s disease and in frontal lobe degeneration. Neurodegeneration 4(2):171–177

Butti C, Hof PR (2010) The insular cortex: a comparative perspective. Brain Struc Func 214(5–6). doi:10.1007/s00429-010-0264-y (this issue)

Craig AD (2009) How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci 10(1):59–70

Critchley HD (2005) Neural mechanisms of autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration. J Comp Neurol 493(1):154–166

Damasio AR (1999) The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Harcourt, Orlando, FL

Di Martino A, Ross K, Uddin LQ, Sklar AB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP (2009) Functional brain correlates of social and nonsocial processes in autism spectrum disorders: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 65(1):63–74

Dosenbach NU, Visscher KM, Palmer ED, Miezin FM, Wenger KK, Kang HC, Burgund ED, Grimes AL, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE (2006) A core system for the implementation of task sets. Neuron 50(5):799–812

Dronkers NF (1996) A new brain region for coordinating speech articulation. Nature 384(6605):159–161

Dunbar RI, Shultz S (2007) Evolution in the social brain. Science 317(5843):1344–1347

Ebneth A, Godemann R, Stamer K, Illenberger S, Trinczek B, Mandelkow E (1998) Overexpression of tau protein inhibits kinesin-dependent trafficking of vesicles, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol 143(3):777–794

Eslinger PJ, Dennis K, Moore P, Antani S, Hauck R, Grossman M (2005) Metacognitive deficits in frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76(12):1630–1635

Fornito A, Yucel M, Patti J, Wood SJ, Pantelis C (2009) Mapping grey matter reductions in schizophrenia: an anatomical likelihood estimation analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Schizophr Res 108(1–3):104–113

Franceschi M, Anchisi D, Pelati O, Zuffi M, Matarrese M, Moresco RM, Fazio F, Perani D (2005) Glucose metabolism and serotonin receptors in the frontotemporal lobe degeneration. Ann Neurol 57(2):216–225

Frost B, Diamond MI (2009) Prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 11(3):155–159

Fujii R, Okabe S, Urushido T, Inoue K, Yoshimura A, Tachibana T, Nishikawa T, Hicks GG, Takumi T (2005) The RNA binding protein TLS is translocated to dendritic spines by mGluR5 activation and regulates spine morphology. Curr Biol 15(6):587–593

Gallup GG Jr (1982) Self-awareness and the emergence of mind in primates. Am J Primatol 2:237–248

Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, Ogar JM, Phengrasamy L, Rosen HJ, Johnson JK, Weiner MW, Miller BL (2004) Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 55(3):335–346

Hakeem AY, Sherwood CC, Bonar CJ, Butti C, Hof PR, Allman JM (2009) Von Economo neurons in the elephant brain. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 292(2):242–248

Hodges JR, Patterson K, Tyler LK (1994) Loss of semantic memory: implications for the modularity of mind. Cogn Neuropsychol 11(5):505–542

Hodges J, Bozeat S, Ralph M, Patterson K, Spatt J (2000) The role of conceptual knowledge in object use evidence from semantic dementia. Brain 123(9):1913–1925

Hodges JR, Davies RR, Xuereb JH, Casey B, Broe M, Bak TH, Kril JJ, Halliday GM (2004) Clinicopathological correlates in frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol 56(3):399–406

Hof PR, Van der Gucht E (2007) Structure of the cerebral cortex of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae (Cetacea, Mysticeti, Balaenopteridae). Anat Rec (Hoboken) 290(1):1–31

Ibach B, Poljansky S, Marienhagen J, Sommer M, Manner P, Hajak G (2004) Contrasting metabolic impairment in frontotemporal degeneration and early onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 23(2):739–743

Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, Layton KF, Parisi JE, Hauser MF, Witte RJ, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Dickson DW, Jack CR Jr, Petersen RC (2006) Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain 129(Pt 6):1385–1398

Kertesz A, McMonagle P, Blair M, Davidson W, Munoz DG (2005) The evolution and pathology of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 128(Pt 9):1996–2005

Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET (2004) The functional neuroanatomy of the human orbitofrontal cortex: evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology. Prog Neurobiol 72(5):341–372

Kurth F, Zilles K, Fox PT, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB (2010) A link between the systems: functional differentiation and intergration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Struc Func 214(5–6). doi:10.1007/s00429-010-255-z (this issue)

Lough S, Kipps CM, Treise C, Watson P, Blair JR, Hodges JR (2006) Social reasoning, emotion and empathy in frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia 44(6):950–958

Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Alafuzoff I, Kril J, Kovacs GG, Ghetti B, Halliday G, Holm IE, Ince PG, Kamphorst W, Revesz T, Rozemuller AJ, Kumar-Singh S, Akiyama H, Baborie A, Spina S, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Mann DM (2010) Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update. Acta Neuropathol 119(1):1–4

Mendez MF, Shapira JS (2009) Altered emotional morality in frontotemporal dementia. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 14(3):165–179

Mendez MF, Anderson E, Shapira JS (2005) An investigation of moral judgement in frontotemporal dementia. Cogn Behav Neurol 18(4):193–197

Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ (1982a) Insula of the old world monkey: I. Architectonics in the insulo-orbito-temporal component of the paralimbic brain. J Comp Neurol 212(1):1–22

Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ (1982b) Insula of the old world monkey. III: efferent cortical output and comments on function. J Comp Neurol 212(1):38–52

Mesulam M, Wicklund A, Johnson N, Rogalski E, Leger GC, Rademaker A, Weintraub S, Bigio EH (2008) Alzheimer and frontotemporal pathology in subsets of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 63(6):709–719

Miller BL, Chang L, Mena I, Boone K, Lesser IM (1993) Progressive right frontotemporal degeneration: clinical, neuropsychological and SPECT characteristics. Dementia 4(3–4):204–213

Mutschler I, Wieckhorst B, Kowalevski S, Derix J, Wentlandt J, Schulze-Bonhage A, Ball T (2009) Functional organization of the human anterior insular cortex. Neurosci Lett 457(2):66–70

Nanetti L, Cerliani L, Gazzola V, Renken R, Keysers C (2009) Group analyses of connectivity-based cortical parcellation using repeated k-means clustering. Neuroimage 47(4):1666–1677

Naqvi NH, Bechara A (2009) The hidden island of addiction: the insula. Trends Neurosci 32(1):56–67

Nauta WJ (1971) The problem of the frontal lobe: a reinterpretation. J Psychiatr Res 8(3):167–187

Nestor PJ, Graham NL, Fryer TD, Williams GB, Patterson K, Hodges JR (2003) Progressive non-fluent aphasia is associated with hypometabolism centred on the left anterior insula. Brain 126(Pt 11):2406–2418

Nimchinsky EA, Gilissen E, Allman JM, Perl DP, Erwin JM, Hof PR (1999) A neuronal morphologic type unique to humans and great apes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96(9):5268–5273

Palop JJ, Chin J, Mucke L (2006) A network dysfunction perspective on neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443(7113):768–773

Penfield W, Faulk ME Jr (1955) The insula: further observations on its function. Brain 78(4):445–470

Pereira JM, Williams GB, Acosta-Cabronero J, Pengas G, Spillantini MG, Xuereb JH, Hodges JR, Nestor PJ (2009) Atrophy patterns in histologic vs clinical groupings of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 72(19):1653–1660

Rabinovici GD, Seeley WW, Kim EJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rascovsky K, Pagliaro TA, Allison SC, Halabi C, Kramer JH, Johnson JK, Weiner MW, Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Dearmond SJ, Miller BL, Rosen HJ (2007) Distinct MRI atrophy patterns in autopsy-proven Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 22(6):474–488

Rankin KP, Gorno-Tempini ML, Allison SC, Stanley CM, Glenn S, Weiner MW, Miller BL (2006) Structural anatomy of empathy in neurodegenerative disease. Brain 129(Pt 11):2945–2956

Richards BA, Chertkow H, Singh V, Robillard A, Massoud F, Evans AC, Kabani NJ (2009) Patterns of cortical thinning in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging 30(10):1626–1636

Roberson ED, Hesse JH, Rose KD, Slama H, Johnson JK, Yaffe K, Forman MS, Miller CA, Trojanowski JQ, Kramer JH, Miller BL (2005) Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology 65(5):719–725

Rohrer JD, Warren JD, Modat M, Ridgway GR, Douiri A, Rossor MN, Ourselin S, Fox NC (2009) Patterns of cortical thinning in the language variants of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 72(18):1562–1569

Rose M (1928) Die inselrinde des menschen und der tiere. J Psychol Neurol 37:468–624

Rosen HJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Goldman WP, Perry RJ, Schuff N, Weiner M, Feiwell R, Kramer JH, Miller BL (2002) Patterns of brain atrophy in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. Neurology 58(2):198–208

Rosen HJ, Allison SC, Schauer GF, Gorno-Tempini ML, Weiner MW, Miller BL (2005) Neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural disorders in dementia. Brain 128(Pt 11):2612–2625

Rotge JY, Guehl D, Dilharreguy B, Cuny E, Tignol J, Bioulac B, Allard M, Burbaud P, Aouizerate B (2008) Provocation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a quantitative voxel-based meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. J Psychiatry Neurosci 33(5):405–412

Salehi A, Delcroix JD, Mobley WC (2003) Traffic at the intersection of neurotrophic factor signaling and neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci 26(2):73–80

Saper CB (2002) The central autonomic nervous system: conscious visceral perception and autonomic pattern generation. Annu Rev Neurosci 25:433–469

Saper CB, Loewy AD (1980) Efferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. Brain Res 197(2):291–317

Schienle A, Schafer A, Hermann A, Vaitl D (2009) Binge-eating disorder: reward sensitivity and brain activation to images of food. Biol Psychiatry 65(8):654–661

Schroeter ML, Raczka K, Neumann J, von Cramon DY (2006) Neural networks in frontotemporal dementia—a meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging 29(3):418–426

Seeley WW (2008) Selective functional, regional, and neuronal vulnerability in frontotemporal dementia. Curr Opin Neurol 21(6):701–707

Seeley WW, Bauer AM, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML, Kramer JH, Weiner M, Rosen HJ (2005) The natural history of temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 64(8):1384–1390

Seeley WW, Carlin DA, Allman JM, Macedo MN, Bush C, Miller BL, Dearmond SJ (2006) Early frontotemporal dementia targets neurons unique to apes and humans. Ann Neurol 60(6):660–667

Seeley WW, Allman JM, Carlin DA, Crawford RK, Macedo MN, Greicius MD, Dearmond SJ, Miller BL (2007a) Divergent social functioning in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease: reciprocal networks and neuronal evolution. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 21(4):S50–S57

Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Greicius MD (2007b) Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci 27(9):2349–2356

Seeley WW, Crawford R, Rascovsky K, Kramer JH, Weiner M, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML (2008) Frontal paralimbic network atrophy in very mild behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol 65(2):249–255

Seeley WW, Crawford RK, Zhou J, Miller BL, Greicius MD (2009) Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron 62(1):42–52

Singer T, Critchley HD, Preuschoff K (2009) A common role of insula in feelings, empathy and uncertainty. Trends Cogn Sci 13(8):334–340

Snowden JS, Bathgate D, Varma A, Blackshaw A, Gibbons ZC, Neary D (2001) Distinct behavioural profiles in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 70(3):323–332

Sollberger M, Stanley CM, Wilson SM, Gyurak A, Beckman V, Growdon M, Jang J, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Rankin KP (2009) Neural basis of interpersonal traits in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropsychologia 47(13):2812–2827

Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V (2008) A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105(34):12569–12574

Sturm VE, Rosen HJ, Allison S, Miller BL, Levenson RW (2006) Self-conscious emotion deficits in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain 129(Pt 9):2508–2516

Sturm VE, Ascher EA, Miller BL, Levenson RW (2008) Diminished self-conscious emotional responding in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Emotion 8(6):861–869

Taylor KS, Seminowicz DA, Davis KD (2009) Two systems of resting state connectivity between the insula and cingulate cortex. Hum Brain Mapp 30(9):2731–2745

Uddin LQ, Menon V (2009) The anterior insula in autism: under-connected and under-examined. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33(8):1198–1203

Varrone A, Pappata S, Caraco C, Soricelli A, Milan G, Quarantelli M, Alfano B, Postiglione A, Salvatore M (2002) Voxel-based comparison of rCBF SPET images in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease highlights the involvement of different cortical networks. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 29(11):1447–1454

von Economo C (1926) Eine neue Art Spezialzellen des Lobus cinguli und Lobus insulae. Z Ges Neurol Psychiatr 100:706–712

von Economo C, Kosinkas GN (1925) Die Cytoarchitektonik der Hirnrinde des Erwachsenen Menschen. Springer, Berlin

Walter H, Kammerer H, Frasch K, Spitzer M, Abler B (2009) Altered reward functions in patients on atypical antipsychotic medication in line with the revised dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 206(1):121–132

Wang GJ, Tomasi D, Backus W, Wang R, Telang F, Geliebter A, Korner J, Bauman A, Fowler JS, Thanos PK, Volkow ND (2008) Gastric distention activates satiety circuitry in the human brain. Neuroimage 39(4):1824–1831

Werner KH, Roberts NA, Rosen HJ, Dean DL, Kramer JH, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Levenson RW (2007) Emotional reactivity and emotion recognition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 69(2):148–155

Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, Rossor MN, Stevens JM, Revesz T, Holton JL, Al-Sarraj S, Godbolt AK, Fox NC, Warren JD (2005) Magnetic resonance imaging signatures of tissue pathology in frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol 62(9):1402–1408

Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr, Senjem ML, Parisi JE, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Josephs KA (2009a) MRI correlates of protein deposition and disease severity in postmortem frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurodegener Dis 6(3):106–117

Whitwell JL, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, Ivnik RJ, Vemuri P, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Shiung MM, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr, Josephs KA (2009b) Distinct anatomical subtypes of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia: a cluster analysis study. Brain 132(Pt 11):2932–2946

Woolley JD, Gorno-Tempini ML, Seeley WW, Rankin K, Lee SS, Matthews BR, Miller BL (2007) Binge eating is associated with right orbitofrontal–insular–striatal atrophy in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 69(14):1424–1433

Zahn R, Moll J, Iyengar V, Huey ED, Tierney M, Krueger F, Grafman J (2009) Social conceptual impairments in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with right anterior temporal hypometabolism. Brain 132(Pt 3):604–616

Zhou J, Greicius MD, Gennatas ED, Growdon ME, Jang JY, Rabinovici GD, Kramer JH, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Seeley WW (2010) Divergent network connectivity changes in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 133(Pt 5):1352–1367

Acknowledgments

I thank my patients, their families, and my colleagues for their contributions to this work. Research reviewed here was supported by NIA grant numbers AG027086, AG19724, AG033017, and AG1657303; the James S. McDonnell Foundation; John Douglas French Foundation; and the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Seeley, W.W. Anterior insula degeneration in frontotemporal dementia. Brain Struct Funct 214, 465–475 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-010-0263-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-010-0263-z