Abstract

Purpose

We examine the association between prior C-section and subsequent pre-eclampsia; and describe the effect of gestational age at prior C-section, and obesity status on this association.

Methods

The study population included women with two subsequent singleton births in Missouri between 1998 and 2005. The risk for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia was assessed among women with and without prior cesarean delivery. The two groups were followed to their second pregnancy and the occurrence of pre-eclampsia was documented. Additionally, the history of pre-eclampsia, prior cesarean at preterm, and obesity status were examined for their differential effects on the risk of pre-eclamsia.

Results

Women with prior C-section were 28% more likely to have pre-eclampsia in their subsequent pregnancy [OR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.20–1.37]. However, this result was not significant when women with pre-eclampsia in their first pregnancy were excluded. After this exclusion, a more than threefold increased risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia was observed in women with prior early C-section [OR = 3.15; 95% CI= 2.43–4.08], while the level of risk did not change in the prior late C-section group [OR = 0.90; 95% CI= 0.82–1.00]. Subgroup analysis suggested that obesity status modified the risk of prior early C-section but did not affect the risk for prior late C-section.

Conclusion

Preterm C-section in the first pregnancy may be associated with subsequent pre-eclampsia regardless of prior pre-eclampsia status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rate of cesarean delivery in the United States has continued to increase over the past decade, and this is a major concern as cesarean deliveries have been associated with higher risks for adverse maternal and infant health outcomes as compared to vaginal births [1–5]. Importantly, a number of adverse pregnancy outcomes have been associated with previous cesarean sections, and include higher risks of abnormalities of placentation, uterine scar dehiscence, uterine rupture, and unexplained fetal death in subsequent pregnancies [5–7].

The risk of pre-eclampsia in the second pregnancy following prior cesarean delivery has not received sufficient attention. In the study conducted by Daltveit et al. [8] in Norway, about threefold increased risk for pre-eclampsia following cesarean delivery was noted. Although the magnitude of risk decreased when women with prior pre-eclampsia were included in the model as potential confounders, the risk still remained statistically significant. Thus, the authors cautioned that any analysis of complications in pregnancies following a cesarean delivery should adjust for prior obstetric history [8]. However, the quoted study did not examine the relationship between prior cesarean section and subsequent pre-eclampsia by gestational age that the procedure was done and by obesity status, a variable that has been shown by us and others to be of immense importance in terms of risk estimation for adverse pregnancy outcomes, especially in population-based studies [9–14]. In this study, we explored the link between exposure to cesarean section in the first pregnancy and subsequent risk for pre-eclampsia in the second pregnancy by obesity status and gestational age at prior cesarean.

Materials and methods

We used the Missouri maternally linked cohort data file which covers the period from 1989 through 2005. The study included all women who delivered their first and second singleton infant in Missouri between 1989 and 2005. The Missouri data contain information on both live birth and fetal death for each sibling, and provides a platform for a longitudinal study of maternal complications and birth outcomes for each pregnancy. Unique identifiers were used to link siblings to their biologic mothers. Previous researchers have detailed the methods and algorithm used in linking birth data into sibships [15] and the dataset has been adopted as “gold standard” to validate U.S. national datasets that involve matching and linking procedures [16].

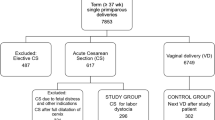

We selected in this study women with first and second singleton pregnancies within the gestational age range of 20–44 weeks (n = 476,173). We excluded 12,342 (2.6%) records with missing pre-eclampsia, eclampsia or implausible birth weight values, 320 (<0.1%) cases with inter-pregnancy interval <28 days and 129,767 (27.3%) cases that were not sibling pairs. A final sample of 166,712 women was then classified into an exposed group that included women who delivered by cesarean section in the first pregnancy and an unexposed group that comprised mothers who had vaginal delivery in their first pregnancy. Previous studies have observed that prior cesarean section affects fetal and maternal outcomes differently by gestational age of prior cesarean [17]. It is based on this published source that we further classified women with prior cesarean section according to the gestational age of the procedure into two groups: cesarean section before 34 weeks of gestation or prior early cesarean section and cesarean section at ≥34 weeks of gestation or prior late cesarean section.

Pre-eclampsia during the second pregnancy was the outcome of interest and was defined as a new onset of hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) after 20 weeks of gestation accompanied by proteinuria (0.3 g or greater in a 24-h urine specimen) or eclampsia (defined as the occurrence of generalized convulsion and/or coma in the setting of pre-eclampsia, with no other neurological condition) [18] as noted in the Missouri database. For ease of presentation and discussion, we will refer to all cases of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia as “pre-eclampsia” in this paper. To investigate confounding effect of women with prior pre-eclampsia in our analysis, two models were generated; Model 1 (study population including women with prior pre-eclampsia) and Model 2 (study population excluding women with prior pre-eclampsia).

Gestational age in the Missouri database was computed in weeks as the interval between the date of last menstrual period and the date of delivery of the baby. When menstrual estimate of gestational age and birth weight (e.g. low birth weight and birth weight at term) were inconsistent, a clinical estimate of the gestational age was used [19]. A validation study was performed on this method of computing the gestational age, with an 84.2% agreement between date of last menses among cases (very low birth weight infants or neonatal deaths) and a randomly selected non-case population [20]. Hence, the use of both methods in this study is reasonably acceptable.

Because certain maternal characteristics (e.g., age of the mother) could influence outcomes in general and since the end-point of interest (namely, pre-eclampsia in the subsequent pregnancy) was more likely to be influenced by maternal characteristics in the second pregnancy than in the first, we compared the following socio-demographic characteristics between the two groups in the second pregnancy, and also adjusted for them in subsequent multivariable analyses. The covariates include: maternal age [<35 years vs. ≥35 years old], marital status [married vs. not married], educational status [<12 years vs. ≥12 years of education], maternal smoking during pregnancy [yes vs. no], maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) defined as maternal pre-pregnancy weight/height (m)2 as reported during the first prenatal visit [categorized as <30 or non-obese vs. ≥30 kg/m2 or obese], adequacy of prenatal care utilization [adequate care vs. inadequate care], gender of the infant [male vs. female] and year of birth of the infant. Adequacy of prenatal care was assessed using the revised graduated index algorithm [21, 22], which was based on three variables (trimester prenatal care began, number of visits, and the gestational age of the infant at birth).

Selected maternal complications in the second pregnancy (anemia, cardiac disease, type-1 diabetes, other types of diabetes, chronic hypertension, placental abruption, placenta previa, and renal disease) were compared between the two groups (prior cesarean section vs. prior vaginal birth) and were included in the multivariable model as a composite variable (anemia, cardiac disease, type-1 diabetes, other types of diabetes, chronic hypertension, placental abruption, placenta previa, and renal disease).

Chi-square test was used to compare baseline characteristics between women with prior cesarean section and women with prior vaginal birth. Unconditional logistic regression (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, version 9.2) was used to model history of cesarean section as a determinant of subsequent pre-eclampsia. Odds ratios (OR) were adjusted for maternal socio-demographic characteristics and the composite variable for pregnancy complications. The exposure of interest, prior cesarean delivery, was examined as a dichotomous variable (yes/no), as well as a variable with three levels of exposure (prior early cesarean, prior late cesarean, vs. prior vaginal birth [referent category]). The effect modification by obesity status was examined in the logistic regression models by including interaction terms between obesity status and prior cesarean (yes/no), and between obesity status and a variable that includes prior early cesarean, prior late cesarean and prior vaginal (referent category) deliveries [23]. All tests of hypothesis were two-tailed with a type 1 error rate fixed at 5%. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of South Florida.

Results

Of the 166,712 women in the Missouri database covering the period from 1989 to 2005 that met the inclusion criteria, 34,339 (20.6%) had cesarean section deliveries in their first pregnancy and 132,373 (79.4) had vaginal birth. Among women with a history of cesarean delivery, 1,450 had prior early cesarean and the remaining 32,889 women had prior late cesarean section delivery. Table 1 depicts results of crude frequency comparison of some selected maternal characteristics and pregnancy complications in the second pregnancy between the two groups. The exposed group (prior cesarean section) was more likely to be older, obese, educated, non-smokers, had higher proportion of adequate prenatal care, white and married compared to the unexposed group (prior vaginal birth) that had a larger proportion of blacks.

Women who were exposed had on average, longer inter-pregnancy interval as compared with the control group (mean ± standard deviation = 893 ± 700 days vs. 863 ± 686 days, respectively; p < 0.01). Overall, prevalence of any pregnancy complication as defined by a composite measure was 6.3%; 8.4% in the exposed group versus 5.7% in the unexposed group (p < 0.01). Most of the individual obstetric/medical complications (i.e., cardiac disease, type I diabetes and other forms of diabetes, chronic hypertension, placental abruption and placenta previa) were more frequent among women with a history of cesarean section delivery. The prevalence of anemia and renal disease did not differ between the two groups (Table 1).

A total of 5,000 pre-eclamptic women were identified in the second pregnancy. Pre-eclampsia developed among 6.7% women with prior cesarean; and among 2.2% women with prior vaginal birth (p < 0.01). The rate of pre-eclampsia was 155 per 1,000 live births in women that had prior early cesarean section and 36 per 1,000 in women that had prior late cesarean section (p value < 0.01). The adjusted estimates for the risk of pre-eclampsia in women with prior cesarean section are presented in Table 3. Women in the cesarean group were 28% more likely to have pre-eclampsia in their subsequent pregnancy compared to the vaginal group [OR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.20–1.37] (Table 2; Model 1). When women with prior cesarean delivery were further classified according to the gestational age at which the procedure was performed, a more than fivefold increased risk of subsequent pre-eclampsia was observed in women with prior early cesarean section [OR = 5.36; 95% CI = 4.61–6.24] compared to only 12% increased risk in women with prior late cesarean section (Table 2; Model 1).

When 11,297 (6.8%) women with pre-eclampsia in their first pregnancy were removed from the analysis, no difference in risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia was observed in the cesarean group compared to the vaginal group overall. After this exclusion, a more than threefold increased risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia was observed in women with prior early C-section [OR = 3.15; 95% CI = 2.43–4.08], while the level of risk did not change in the prior late C-section group [OR = 0.90; 95% CI = 0.82–1.00]. (Table 2; Model 2).

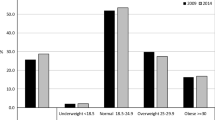

In the entire study population, 20.6% of the women were obese, while the remaining 79.4% were non-obese. Women who were obese were about 2 times more in the prior C-section group compared to the prior vaginal group (26.4 vs. 15.6%) [p value < 0.01]. This ratio stayed the same even when women with prior pre-eclampsia were excluded from the analysis (24.5 vs. 15.6%) [p value < 0.01]. Figure 1 shows the rates of pre-eclampsia in obese versus non-obese women by prior early and late cesarean delivery among mothers without previous history of pre-eclampsia.

A multiple logistic model that includes an interaction between obesity status and prior cesarean was statistically significant [deviance p value = <0.01], and between obesity status and prior cesarean delivery categorized as prior early cesarean, prior late cesarean and prior vaginal delivery was significant [deviance p value < 0.01]. The same result was observed even when women with prior pre-eclampsia were not included in the analysis. This subgroup analysis by obesity status suggested that obese mothers had higher odds for subsequent pre-eclampsia when compared to non-obese mothers irrespective of their prior delivery status and the model used (the respective confidence intervals did not intersect) [Table 3]. Also noted in this study was the reduced odds for pre-eclampsia in non-obese women with late cesarean delivery compared to their counterparts who had prior vaginal delivery. Although the risk in obese women who had prior late C-section was lower, it did not reach statistical significance. A similar result was observed when women with prior pre-eclampsia were removed from the study population (Table 3; Model 2).

Discussion

We observed a 28% increased risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia in women with prior cesarean delivery. When these women were categorized according to the gestational age at the time of the procedure, there was a 12% increased risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia in women with prior late cesarean and a more than fivefold increased risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia in women with prior early cesarean delivery. However, exclusion of women with pre-eclampsia in their first pregnancy revealed that only the sub-category of women with prior early cesarean had increased risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia. Consequently, the increased risk for pre-eclampsia in women with prior late cesarean delivery could be explained by the presence of pre-eclampsia in the first pregnancy. Previous authors have established that pre-eclampsia in previous pregnancy is a risk factor for pre-eclampsia and other adverse pregnancy outcomes in subsequent pregnancies [24–27].

In a cohort of 637,497 women in Norway, Daltveit et al. [8] observed a 70% increased risk of pre-eclampsia in the second pregnancy in women who had prior cesarean section compared to women that had prior vaginal delivery even when women with pre-eclampsia in the first pregnancy were excluded from the study. The discrepancy between the Norwegian study and ours might be due to differences in the indications for previous cesarean section. It is known that the rate of cesarean section in Scandinavian countries in general is significantly lower than in the US [3, 8], an indication that perhaps cesarean sections in Norway will be generally performed for more severe morbidity, and thus more likely lead to pre-eclampsia in a subsequent pregnancy, as these morbidities may share similar risk factors as pre-eclampsia.

Unique to this study is the observation that women with prior early cesarean delivery were at an increased risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia even when women with pre-eclampsia in the first pregnancy were excluded from the study. Previous studies have established a link between prior preterm delivery and subsequent pre-eclampsia [24]. The prevalence of overall complication (anemia, cardiac disease, type-1 diabetes, other types of diabetes, chronic hypertension, placental abruption, placenta previa, and renal disease) in the first pregnancy was 19.7% in women with prior early cesarean delivery, 7.5% in women with prior late cesarean delivery and 4.1% in women with prior vaginal birth. These complications have been shown to be associated with subsequent pre-eclampsia [28–30]. The high prevalence of complications in the previous pregnancy in women with prior early cesarean delivery could explain the increased risk for subsequent pre-eclampsia in this group of women. Furthermore, prior cesarean sections have been shown to be an important risk factor for subsequent complications including placental vasculopathies [31], and since pre-eclampsia is etiologically a placental disease [32], this might be additional explanation for our findings.

Subgroup analysis revealed obesity status as an effect modifier between prior cesarean section and pre-eclampsia. Interestingly, we did not observe any significant odds for pre-eclampsia in obese women with prior late cesarean section compared to their counterparts with prior vaginal birth. Additionally, the odds for pre-eclampsia was modified in normal weight women with prior late C-section. This also strengthens the earlier argument that if C-section is to be performed, it should occur after 34 weeks of gestation.

The findings in this study should be interpreted bearing certain limitations in mind. Our results could have been biased due to the long period of follow-up of the Missouri dataset (1998–2005), since we analyzed data from different cohorts of women. However, because we controlled for year of birth in the model, this bias was reduced to a minimum. The strength in this study includes a large sample size that is population-based, unique information on racial disparity regarding subsequent risk for pre-eclampsia following prior cesarean section, and stratified analyses based on gestational age at cesarean section in the prior pregnancy.

In summary, we found cesarean section (specifically before 34 weeks) in the first pregnancy to be a risk factor for subsequent pre-eclampsia regardless of prior pre-eclampsia status. This information is potentially useful to care providers for counseling women who have been exposed to cesarean section, and for ante-partum surveillance in subsequent pregnancies.

References

Allen VM, O’Connell CM, Liston RM, Baskett TF (2003) Maternal morbidity associated with cesarean delivery without labor compared with spontaneous onset of labor at term. Obstet Gynecol 102(3):477–482

Belizán JM, Althabe F, Cafferata ML (2007) Health consequences of the increasing caesarean section rates. Epidemiology 18(4):485–486

Declercq E, Barger M, Cabral HJ et al (2007) Maternal outcomes associated with planned primary cesarean births compared with planned vaginal births. Obstet Gynecol 109(3):669–677

Miesnik SR, Reale BJ (2007) A review of issues surrounding medically elective cesarean delivery. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 36(6):605–615

Gilliam M (2006) Cesarean delivery on request: reproductive consequences. Semin Perinatol 30(5):257–260

Smith GC, Pell JP, Dobbie R (2003) Caesarean section and risk of unexplained stillbirth in subsequent pregnancy. Lancet 362(9398):1779–1784

Spong CY, Landon MB, Gilbert S, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network et al (2007) Risk of uterine rupture and adverse perinatal outcome at term after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 110(4):801–807

Daltveit AK, Tollånes MC, Pihlstrøm H, Irgens LM (2008) Cesarean delivery and subsequent pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 111(6):1327–1334

Salihu HM, Weldeselasse HE, Rao K, Marty PJ, Whiteman VE (2011) The impact of obesity on maternal morbidity and feto-infant outcomes among macrosomic infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med [Epub ahead of print]

Mbah AK, Kornosky JL, Kristensen S et al (2010) Super-obesity and risk for early and late pre-eclampsia. BJOG 117(8):997–1004 [Epub 2010 May 19]

Salihu HM, Lynch O, Alio AP, Kornosky JL, Clayton HB, Mbah AK (2009) Extreme obesity and risk of placental abruption. Hum Reprod 24(2):438–444 (Epub 2008 Dec)

Begum KS, Sachchithanantham K, De Somsubhra S (2011) Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 38(1):14–20 (Review)

Gunatilake RP, Perlow JH (2011) Obesity and pregnancy: clinical management of the obese gravida. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204(2):106–119 (Review)

Murakami M, Ohmichi M, Takahashi T, Shibata A, Fukao A, Morisaki N, Kurachi H (2005) Prepregnancy body mass index as an important predictor of perinatal outcomes in Japanese. Arch Gynecol Obstet 271(4):311–315 [Epub 2004 Jun 5]

Herman AA, McCarthy BJ, Bakewell JM et al (1997) Data linkage methods used in maternally-linked birth and infant death surveillance datasets from the United States (Georgia, Missouri, Utah and Washington State), Israel, Norway, Scotland and Western Australia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 11(suppl):5–22

Martin J, Curtin S, Saulnier M, Mousavi J (2003) Development of the matched multiple birth file. In: 1995–1998 matched multiple birth dataset. NCHS CD-ROM series 21, no. 13a. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville

Smith GC, Pell JP, Cameron AD, Dobbie R (2002) Risk of perinatal death associated with labor after previous cesarean delivery in uncomplicated term pregnancies. JAMA 287(20):2684–2690

Hernández-Díaz S, Toh S, Cnattingius S (2009) Risk of pre-eclampsia in first and subsequent pregnancies: prospective cohort study. BMJ 338:b2255 doi:10.1136/bmj.b2255

Taffel S, Johnson D, Heuser R (1982) A method of imputing length of gestation on birth certificates. Vital Health Stat 93:1–11

Piper JM, Mitchel EF Jr, Snowden M, Hall C, Adams M, Taylor P (1993) Validation of 1989 Tennessee birth certificates using maternal and newborn hospital records. Am J Epidemiol 137(7):758–768

Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M (1996) Quantifying the adequacy of prenatal care: a comparison of indices. Public Health Rep 3:408–418

Alexander GR, Cornely DA (1987) Prenatal care utilization: its measurement and relationship to pregnancy outcome. Am J Prevent Med 3:243–253

Breslow NE, Day NE (1980) Statistical methods in cancer research, vol. I—The analysis of case-control studies. IARC, Lyon Scientific Publ. No 32

Lykke JA, Paidas MJ, Langhoff-Roos J (2009) Recurring complications in second pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 113(6):1217–1224

Barton JR, Sibai BM (2008) Prediction and prevention of recurrent preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 112(2 Pt 1):359–372

Mostello D, Kallogjeri D, Tungsiripat R, Leet T (2008) Recurrence of preeclampsia: effects of gestational age at delivery of the first pregnancy, body mass index, paternity, and interval between births. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199(1):55.e1–55.e7 [Epub 2008 Feb 15]

Mendilcioglu I, Trak B, Uner M, Umit S, Kucukosmanoglu M (2004) Recurrent preeclampsia and perinatal outcome: a study of women with recurrent preeclampsia compared with women with preeclampsia who remained normotensive during their prior pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 83(11):1044–1048

Tollånes MC (2009) Increased rate of Caesarean sections–causes and consequences. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 129(13):1329–1331

Getahun D, Oyelese Y, Salihu HM, Ananth CV (2006) Previous cesarean delivery and risks of placenta previa and placental abruption. Obstet Gynecol 107(4):771–778

Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP (2001) First-birth cesarean and placental abruption or previa at second birth (1). Obstet Gynecol 97(5 Pt 1):765–769

Hemminki E, Merilainen J (1996) Long-term effects of cesarean sections: ectopic pregnancies and placental problems. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174:1569–1574

Ananth CV, Peltier MR, Chavez MR, Kirby RS, Getahun D, Vintzileos AM (2007) Recurrence of ischemic placental disease. Obstet Gynecol 110(1):128–133

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the James & Esther King Biomedical Research Program (Grant # 09KN-07-23141) to Dr. Alfred Mbah. The funding agencies did not play any role in any aspect of the study.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mbah, A.K., Sharma, P.P., Alio, A.P. et al. Previous cesarean section, gestational age at first delivery and subsequent risk of pre-eclampsia in obese mothers. Arch Gynecol Obstet 285, 1375–1381 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-2161-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-2161-x