Abstract

The corals Acropora palmata and A. cervicornis are important Caribbean reef-builders that have faced significant mortality in recent decades. While many studies have focused on the recent demise of these species, data from areas where Acropora spp. have continued to thrive are limited. Understanding the genetic diversity, recruitment, and temporal continuity of healthy populations of these threatened Acropora spp. and the hybrid they form (“Acropora prolifera”) may provide insights into the demographic processes governing them. We studied three reef sites with abundant A. cervicornis, A. palmata, and hybrid Acropora populations offshore of Ambergris Caye, Belize at Coral Gardens, Manatee Channel, and Rocky Point. Samples were collected from all three Acropora taxa. We used microsatellite markers to determine: (1) genotypic diversity; (2) dominant reproductive mode supporting local recruitment; (3) minimum and maximum genet age estimates for all three acroporids; and (4) the history of hybrid colonization at these sites. We found that Acropora populations were highly clonal with local recruitment primarily occurring through asexual fragmentation. We also estimated the ages of 10 Acropora genets using recent methodology based on somatic mutation rates from genetic data. Results indicate minimum ages of 62–409 yr for A. cervicornis, 187–561 yr for A. palmata, and 156–281 yr for the Acropora hybrids at these sites. Our data indicate that existing A. cervicornis, A. palmata, and Acropora hybrid genets persisted during the 1980s Caribbean-wide Acropora spp. collapse, suggesting that these sites have been a refuge for Caribbean Acropora corals. Additionally, our data suggest that formation of extant hybrid Acropora genets pre-dates the widespread collapse of the parent taxa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global decline of shallow coral populations in response to increasing sea-surface temperatures, overfishing, rising sea level, disease, eutrophication, sedimentation, and ocean acidification has been well documented (Hughes 1994; Hughes et al. 2003; Bellwood et al. 2004; Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2007; Kuffner et al. 2015). Caribbean populations of Acropora cervicornis and A. palmata (Fig. 1), two of the most important Caribbean reef framework-builders, have experienced up to 98% mortality over just a few decades in response to increasing environmental stress and disease prevalence (Gladfelter 1982; Aronson and Precht 2001; Pandolfi 2002; Gardner et al. 2003; Eakin et al. 2010; Randall and van Woesik 2015). Consequently, these were the first two coral species listed as threatened under the US Endangered Species Act (NOAA 2005).

Despite Caribbean-wide declines, relatively abundant A. cervicornis and A. palmata populations have been reported in Honduras (Keck et al. 2005; Purkis et al. 2006), the Dominican Republic (Lirman et al. 2010), Mexico (Larson et al. 2014), Florida (Fort Lauderdale area; Vargas-Angel et al. 2003), and Belize (Peckol et al. 2003; Brown-Saracino et al. 2007; Macintyre and Toscano 2007; Busch et al. 2016). These studies have variably included general habitat surveys, quantification of percentage of algal and live coral coverage, Acropora colony sizes, number of Acropora colonies, fish and invertebrate population densities, image-based spatial characterization, and disease prevalence, but none included genetic data.

Genotypic diversity (the number of distinct genotypes or clones per species per site) is a critical factor when assessing the long-term population trends and evolutionary potential of these sites because Caribbean acroporids do not self-fertilize and thus sexual reproduction requires the presence of several genotypes (Szmant 1986; Baums et al. 2005a, 2006; Fogarty et al. 2012). Clonal reproduction is also an important process in many populations. Caribbean acroporids experience frequent breakage due to physical impacts such as storms and anchor damage. Branches are genetically identical to their donor colonies (i.e., ramets of the same genet) and can re-attach to the benthos. Once re-attached they grow into new colonies, usually within tens of meters of the donor colony (Highsmith 1982; Lirman 2000; Baums et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2008). This sometimes results in large areas of a reef dominated by a single genotype (Baums et al. 2006). Genotypic diversity of foundation fauna has been associated with overall population health and has been predicted to have a positive relationship with persistence during adverse conditions by providing a diverse set of alleles to the population (Altizer et al. 2003; Reed and Frankham 2003; Reusch et al. 2005; Downing et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2014). However, recent findings show that genotypic diversity in Acropora populations does not necessarily increase their sustainability over short time scales as predicted (Williams et al. 2014). Thus, the role of genotypic diversity in persistence remains unclear.

Acropora cervicornis and A. palmata hybridize to form “Acropora prolifera”, the only known scleractinian hybrid in the Caribbean (Fig. 1; van Oppen et al. 2000; Vollmer and Palumbi 2002; Willis et al. 2006 ). The hybrid has not been found in the fossil record (Budd et al. 1994) and has been reported as rare compared to its parents (Lang et al. 1998; Willis et al. 2006; Fogarty 2010, 2012). However, recently it has been observed more frequently and in higher abundance in Florida (Wheaton et al. 2006), Curaçao (Fogarty 2010), Honduras (Keck et al. 2005), the Lesser Antilles (Japaud et al. 2014), and Belize (Fogarty 2010; Fogarty et al. 2012; Richards and Hobbs 2015). The apparent recent increase in the hybrid may suggest either that hybridization is now occurring more frequently, or that hybridization has always occurred, but environmental conditions now favor maturation of hybrid larvae over those of the diminishing parent species (Willis et al. 2006).

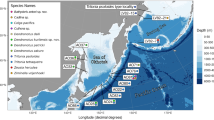

In this study, we analyzed genetic data of A. cervicornis, A. palmata, and the hybrid from Coral Gardens, Manatee Channel, and Rocky Point, sites offshore of Ambergris Caye, Belize, where acroporids are highly abundant (Table 1; Fig. 2). Our specific objectives were to: (1) determine genotypic diversity of Acropora taxa; (2) calculate the degree to which sexual vs asexual recruitment has occurred; (3) estimate the age of Acropora genets; and (4) determine the history and nature of hybrid colonization. We analyzed data from microsatellite loci to identify genets and ramets and subsequently draw inference about the genotypic diversity, as well as the degree of asexual vs sexual reproduction in recruitment to these sites (Baums et al. 2005b). We refer to a “genet” as an assemblage of genetically identical colonies (clones) that are descendants of a single zygote (Harper 1977; Hughes 1989; Carvalho 1994), and a genet’s component colonies as “ramets” (Kays and Harper 1974) or clone mates. A method based on accumulation of somatic mutations in clonal organisms (Weiher et al. 1999; Eriksson 2000; Ally et al. 2008; de Witte and Stocklin 2010), recently adapted to study Acropora genets (Devlin-Durante et al. 2016) was applied to estimate clonal age and assess the history of Acropora spp. and A. prolifera hybrid persistence at these sites. We analyzed clonal age data for all Acropora taxa to determine persistence and, for the hybrid at our study sites, to elucidate the history of its emergence and spread.

Materials and methods

Study site

The three reef sites sampled lie within roughly a 50-km distance between Caye Caulker to the south and the northern end of Ambergris Caye in Belize (Fig. 2). Coral Gardens (17°50′00.36″N, 87°59′32.45″W; Table 1; Fig. 1) is a shallow-water back reef setting with a maximum depth of ~7 m. It is comprised of lagoonal patch reefs dominated by interconnected thickets of A. cervicornis, large peripheral colonies of A. palmata, and small hybrid colonies. The Acropora thickets are interspersed with mixed coral stands dominated by Orbicella, Agaricia, Porites, and Millepora species, and areas of sandy bottom. Peckol et al. (2003) and Brown-Saracino et al. (2007) reported live coral cover (all species) in this area exceeding 43%. More recently, Busch et al. (2016) reported an average value of ~ 30% live A. cervicornis coral cover (species specific) in the Acropora thickets sampled in this study. The extent of live Acropora thickets in the greater Coral Gardens area exceeded 7.5 ha in 2015, making it one of the largest documented sites of its kind in the Caribbean (Busch et al. 2016).

Manatee Channel (17°47′58.08″N, 87°59′45.57″W; Table 1; Fig. 2) is approximately 1–2 m deep and located just inside the reef crest. It is comprised of patch reefs dominated by thickets of the hybrid and scattered stands of A. cervicornis and A. palmata. Acroporid thickets and colonies are surrounded by mixed coral stands dominated by Orbicella, Agaricia, Porites, and Millepora species, and sandy bottom. Manatee Channel has been previously described in the literature by Fogarty (2012) as “north Caye Caulker.”

Rocky Point, (18°12′37.95″N, 87°82′60.64″W; Table 1; Fig. 2), approximately 2–3 m depth, is dominated by individual colonies and small patches of the hybrid, both parent species, and some colonies of Orbicella, Porites, and Siderastrea species (Figs. 2, 3). Rocky Point lies within the Bacalar Chico National Park and Marine Reserve and is the only site among our study locations with marine protected area (MPA) status.

Sampling

Live coral samples of approximately 1 cm3 were collected from Acropora branch tips using surgical bone cutters. Samples were preserved in 95% ethanol and refrigerated prior to DNA extractions. Coral tissue samples were collected from Coral Gardens in June of 2013 and 2014, and from Manatee Channel and Rocky Point in June 2014. In 2013, coral tissue was collected at Coral Gardens from haphazardly selected A. cervicornis colonies (n = 60) within the reef boundary, and each observed colony of A. palmata (n = 78) and the hybrid (n = 48) was sampled. Additional sampling in 2014 was designed to increase the likelihood of sampling ramets of the same genet. At Coral Gardens, A. cervicornis samples (n = 158) were collected from 5-m radius plots in which a center point was designated and samples were collected along four randomly generated headings (at least 5° apart) every 1 m for a total of 20 samples per plot. The likelihood that the same colonies were sampled in 2013 and 2014 is small. At Manatee Channel, hybrid samples (n = 80) were collected using the same circle plot method, with four plots (20 samples per plot) placed at areas of largest abundance and never overlapping. All observed colonies of A. cervicornis (n = 20) and A. palmata (n = 15) across the entire site were also sampled. We defined a colony as a continuous, upright entity of living coral attached to a base or seafloor. At Rocky Point the hybrid was sampled haphazardly (n = 32) due to irregular patch shape. Acropora cervicornis and A. palmata were not sampled at this site.

Genotypic analysis

Nuclear DNA was extracted from tissue of 3–5 polyps using the Qiagen DNEasy kit (Qiagen, Germany) and protocol with the following modifications: (1) we performed proteinase K digestion overnight at 56 °C in a stationary water bath; and (2) precipitates were dissolved in Buffer AL for 10 min at 56 °C in a stationary water bath. We amplified five microsatellite loci (166, 181, 182, 192, 207) via polymerase chain reaction in two multiplexes following methods described by Baums et al. (2005a). Locus 192 does not amplify in A. cervicornis and amplifies only the A. palmata allele in the hybrid (making the marker appear homozygous). Fragment lengths were determined using an ABI 3730 (Gene Scan 500-Liz, Applied Biosystems), and electropherograms were scored using GeneMapper Software 3.0 (Applied Biosystems).

Data analyses

Genotypic diversity

We used data from highly polymorphic microsatellite loci to identify unique genotypes (genets). Samples were considered ramets of the same genet, i.e., genotypically identical colonies arisen from fragmentation, if they have identical genotypes across all five or four loci, or if they have identical genotypes across all five or four (A. cervicornis) loci with an additional allele(s). Because of the smaller number of loci retrieved for A. cervicornis the power to distinguish clonemates from closely related individuals is lower for A. cervicornis (average Pgen = 1.11−04) than the other taxa (A. palmata average Pgen = 2.99−07, hybrid average Pgen = 2.74−05). Nevertheless, using MLGSim 2.0 (Stenberg et al. 2003), we determined that each of the identified genets, regardless of taxon, was highly likely to be the product of random mating within the population (Psex, p < 0.05 for each genet).

In addition, samples with matching genotypes across four or three (A. cervicornis) loci were also considered to be ramets of a single genet if the fifth or fourth (A. cervicornis) locus only differed by single- or double-step mutations. Such genotypic differences among ramets were assumed to arise via mutations in somatic cell lines that can accumulate with age (Devlin-Durante et al. 2016; see below). We calculated diversity metrics following methods described in Baums et al. (2006) as adapted from Stoddart and Taylor (1988). Observed genotypic diversity (G o ) within and among sampling sites for each species was calculated as:

where g i is the relative frequency of an observed genotype among all (k) genotypes. Expected genotypic diversity under the condition of exclusively sexual reproduction (G e ) is assumed equal to the number of colonies sampled (i.e., sample size, n), since only one sample was collected from each separate colony. Thus, the ratio G o /G e provides an index of genotypic diversity within the population that captures the relative degree to which sexual reproduction contributes to recruitment. Genotypic evenness is represented as the ratio of observed genotypic diversity versus genotypic richness (G o /N g ), where N g is the number of unique genets in the sample. Finally, we calculated standardized genotypic richness among and within sites relative to sample size (N g /n). Baums et al. (2006) used these metrics to draw conclusions about the demography of local recruitment, classifying sites with high clonality as “asexual” (most colony recruitment arising from fragmentation) and those with low clonality as “mostly sexual” (recruitment arising from sexual reproduction and settlement of planulae). We used values for these metrics from this study and those from Baums et al. (2006) to make relative inferences about clonal structure and recruitment of Acropora at our sites compared to others in the Caribbean.

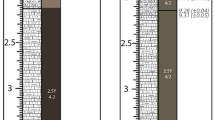

Somatic mutations

Genotypes accumulate somatic mutations over time. Assuming a constant mutation rate, the number of somatic mutations can be used to estimate the age of the genome by applying coalescent methods (Ally et al. 2008). Microsatellites are ideal for estimating genetic divergence because they have high mutation rates and low technical error rates. Hence, they can provide adequate resolution of somatic mutations. A ramet was identified as having a somatic mutation if there was an amplification of an additional allele/s, but alleles were otherwise identical at all five or four (A. cervicornis) loci (Devlin-Durante et al. 2016). While the appearance of an additional allele at a locus (rendering an individual polyploid instead of diploid at this locus) may seem odd, it has been deemed common in A. palmata, and predicted to occur due to genomes accumulating somatic duplications over time.

As somatic gene duplications accumulate, multiple copies of the microsatellite locus become available for replication slippage (Devlin-Durante et al. 2016). For example, consider the case where an unmutated ramet had the ancestral genotype of allele 1 = 160 bp, allele 2 = 172 bp (in short: 160/172) at locus 1, whereas a mutated ramet had alleles of 160/172/175 at locus 1. In this instance, the ramet mutated when its second allele duplicated, and the new third allele underwent a single-step mutation, adding a trinucleotide repeat. Alternatively, one of the alleles may have mutated in some of the cells or polyps without a prior gene duplication event (Devlin-Durante et al. 2016). Because DNA was extracted from multiple polyps, this could also lead to the appearance of three alleles in the electropherograms. A ramet was also identified as having a somatic mutation if it matched a genotype across four or three (A. cervicornis) loci, but at the fifth or fourth (A. cervicornis) locus only differed by single- or double-step mutations.

Next, we required that a genet have at least five ramets, a minimum requirement set by Devlin-Durante et al. (2016) to improve accuracy of aging. The mutation rates established by Devlin-Durante et al. (2016) (lowest = 1.542−05 locus−1 yr−1, highest = 1.195−04 locus−1 yr−1) were then applied to the equation described in Ally et al. (2008) to obtain minimum and maximum ages of each genet. The methods for calculating clonal age using genetic divergence are described in Ally et al. (2008). In brief, there are two statistics, π k and S k , that describe genetic divergence within a clone (Slatkin 1996). We calculated the average number of pairwise differences per locus for the kth clone

where n is the number of sampled ramets and \( s_{ij} \) is the number of genetic differences between ramet i and j averaged across loci (Ally et al. 2008). We chose π k to measure the level of genetic divergence because it has been shown to be more robust to deviations from a starlike phylogeny than S k (the observed proportion of polymorphic loci) (Ally et al. 2008).

Results

Genotypic diversity

Collectively we identified 18 genets among n = 227 individuals of A. cervicornis sampled, 31 genets among n = 92 A. palmata, and 14 genets among n = 147 hybrid samples (Table 2). Acroporids at our study sites showed a range in genotypic diversity suggesting that local recruitment in some locations was predominantly asexual, i.e., supported by fragmentation, while at other sites recruitment was supported to a greater degree by sexual reproduction (Table 2; Fig. 3). At Manatee Channel, all hybrid colonies (n = 70) shared the same genotype and were therefore ramets of a single genet (Table 2; Fig. 3). Thus, recruitment of existing hybrid colonies at Manatee Channel had occurred only through fragmentation from existing colonies. By contrast, A. cervicornis and A. palmata at Manatee Channel showed the highest genotypic diversity (G o /G e = 0.26 and 0.37, respectively) and evenness (G o /N g = 0.62 and 0.69, respectively) among locations,Footnote 1 indicating that a substantial proportion of local recruitment was via sexual reproduction (following Baums et al. 2006; Table 2; Fig. 3). Coral Gardens was characterized by low genotypic diversity across all three taxa, indicating a high degree of asexual recruitment (Table 2; Fig. 3). It is possible but unlikely that a few individual colonies were re-sampled from 2013 to 2014. If so, this could partially contribute to the low genotypic diversity seen at Coral Gardens. Rocky Point, at which only hybrids were sampled, was characterized by low genotypic diversity and predominantly asexual recruitment as well (Table 2; Fig. 3).

Comparison of genotypic diversity and evenness metrics calculated in our study with those calculated by Baums et al. (2006) for Caribbean populations of Acropora palmata, with inference on demography of local recruitment. Values for our locations are labeled by site (MC Manatee Channel, CG Coral Gardens, RP Rocky Point, BZ Belize i.e., all sites combined) and color coded by species (blue: A. cervicornis; red: A. palmata; green: hybrid). Data from Baums et al. (2006) are shown as unfilled circles. Ellipses grouping sites according to relative degree of sexual versus asexual recruitment are redrawn from Fig. 4 in Baums et al. (2006)

When samples were pooled across all three sites, both diversity and evenness metrics were relatively low and indicated predominantly asexual recruitment (Table 2; Fig. 3). Overall, A. palmata showed the highest genotypic diversity (G o /G e = 0.15), evenness (G o /N g = 0.43), and richness (N g /N = 0.34) across all three species (Table 2; Fig. 3). Acropora cervicornis and the hybrid were comparatively much lower in genotypic diversity and richness (Table 2; Fig. 3).

Somatic ages

From our 466 Acropora samples, we were able to calculate preliminary minimum and maximum age estimates for 10 of the 63 genets (Table 3). We were unable to estimate ages for the remaining 53 genets using this method either because we sampled fewer than five ramets of that genet (44 genets) or because there were no observed somatic mutations in the loci amplified (9 genets). In the latter scenario, we concluded these genets lack somatic mutations because they are of recent origin.

At Coral Gardens, A. cervicornis genets were estimated to be between 62 and 460 yr old (two genets), 179–1337 yr old (one genet), 393–2931 yr old (one genet), and 409–3052 yr old (one genet) (Table 3). Acropora palmata genets at this site were estimated to be between 187 and 1397 yr old (one genet), 219–1636 yr old (one genet), and 561–4191 yr old (one genet) (Table 3). A single hybrid genet at this site was estimated to be between 281 and 2096 yr old (Table 3). At Manatee Channel, no somatic mutations were observed at these loci for any A. cervicornis, A. palmata, or hybrid genets. At Rocky Point, we were able to estimate the age for one hybrid genet to be between 156 and 1164 yr old (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we had the rare opportunity to analyze large living stands of ecologically significant Acropora spp. and the hybrid they form, at a time when the existence of acroporids in the Caribbean is in peril. From our collection and analyses of 466 samples, we determined that acroporids offshore of Ambergris Caye, Belize were mostly clonal, with little sexual recruitment. Although genetic diversity was low, we found that both veteran and more recent genets were represented in all three acroporid taxa at these sites. Furthermore, our data suggested that hybrid colonization at some of these sites pre-dated the widespread Caribbean collapse of the parent acroporid species.

The genotypic diversity and evenness of acroporid populations at our study sites was low overall, with the exception of A. palmata and A. cervicornis at Manatee Channel, which exhibited a relatively high degree of genotypic diversity and evenness. From this information, we deduced that there is minimal input from local sexual reproduction or from ‘upstream’ source populations for all three Caribbean acroporids at Coral Gardens and the hybrid at Manatee Channel and Rocky Point. Only the Manatee Channel A. palmata and A. cervicornis samples in our study indicated substantive inputs from sexual reproduction. This may be due to localized variation in current patterns or subsequent differences in delivery or retention of planulae at these sites. A similar prevalence of asexual recruitment was observed by Baums et al. (2006) at a nearby A. palmata population in Chinchorro, Mexico (~49 km north of our northernmost site, Rocky Point), as well as in most other A. palmata populations at Western Caribbean sites (Baums et al. 2005b). Our results further validate their claim that Western Caribbean Acropora populations exhibit little sexual reproduction.

Previous studies from other abundant Acropora sites predicted that large populations were critical sources of propagules that might contribute to genetic diversity and coral coverage at neighboring sites (Keck et al. 2005; Zubillaga et al. 2008; Lirman et al. 2010; Vargas-Angel et al. 2003). However, because Caribbean acroporids usually do not self-fertilize, production of sexual offspring is a function of the number of genotypes present and not just a function of colony density or size (Levitan and McGovern 2005; Fogarty et al. 2012; Baums et al. 2013; Williams et al. 2014). Our study suggests that while Coral Gardens may be the largest extant acroporid site in the Caribbean (Busch et al. 2016), this may not translate into successful downstream sexual recruitment. Only observation of spawning and gamete-crossing experiments at these sites would provide additional insight into the production of gametes by these stands.

Although the genotypic diversity is generally low, our age estimates of acroporid genets vary. Using a new genetic aging technique, we estimated age ranges for 10 genets in this study. While the uncertainty in the age-range estimates may be considerable (Devlin-Durante et al. 2016), we believe that the more conservative minimum age estimates may be valuable at least in distinguishing new from older genets. Our data suggested that both new (minimal somatic mutations) and veteran (minimum ages 62–561 yr) genets co-exist at these sites and that veteran Belize acroporids pre-date the widespread Caribbean collapse of acroporids. Future determination of microsatellite mutation rates in Acropora coral would help to narrow the currently rather wide range for age estimates.

Two of the veteran genets we identified are from hybrid samples. We estimated that these hybrid genets have existed for at least 156 and 281 yr, respectively. It is thought that the hybrid only recently expanded its presence in Caribbean reef areas (Willis et al. 2006; Fogarty 2010; Richards and Hobbs 2015); however, no data on the ages of extant hybrid genets exist in the literature. Here we show that at least a few hybrid genets originated before the Caribbean-wide acroporid die-off event in the 1980s. It is unclear whether the persistence of A. cervicornis, A. palmata, and hybrid veteran genets at our sites is a function of: (1) their innate ability to rebound from disturbances (Eriksson 2000; Riegl et al. 2009); (2) whether certain colonies were simply lucky and survived environmental changes at random; or (3) whether environmental or oceanographic conditions have been particularly conducive to acroporid persistence at these sites.

Our study sites are home to acroporid populations observed in high abundances in a time when they are facing Caribbean-wide decline. The existence of Acropora populations like these provides hope that perhaps these species and their hybrid can continue to persist. However, without analyzing the demographic processes of such populations, their potential resilience cannot be known. Here, we studied genotypic diversity and age in unison. The genotypic diversity of acroporids at our study sites was relatively low, which, considered alone, does not bode well for the potential of these populations to combat future environmental stresses (Schmid 1994; Steinger et al. 1996; Reusch et al. 2005; Garcia et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2008). However, we also know that some of the genets in these populations are relatively old and may have survived past environmental stresses, perhaps due to increased (and unknown) fitness attributes. Such veteran populations have hypothesized potential to expand (Noss 2001; Taberlet and Cheddadi 2002; Loarie et al. 2008; Keppel et al. 2012). Thus, we are left with two contradicting conclusions: the populations have low genotypic diversity so they are vulnerable to environmental change; or the populations have veteran genets whose past fitness may indicate that they will continue to survive in the future. In either scenario, these sites have potential to be valuable resources to Acropora spp. recovery initiatives and should be investigated further. We hope that the methods applied here can be useful to future studies that aim to identify sites of conservation priorities.

Notes

Note that although the calculated value for evenness is highest for A. prolifera hybrid at Manatee Channel (G o /N g = 1), this value is not meaningful as all individuals shared the same genotype.

References

Ally D, Ritland K, Otto SP (2008) Can clone size serve as a proxy for clone age? An exploration using microsatellite divergence in Populus tremuloides. Mol Ecol 17:4897–4911

Altizer S, Harvell D, Friedle E (2003) Rapid evolutionary dynamics and disease threats to biodiversity. Trends Ecol Evol 11:589–596

Aronson RB, Precht WF (2001) White-band disease and the changing face of Caribbean coral reefs. Hydrobiologia 460:25–38

Baums IB, Hughes CR, Hellberg MH (2005a) Mendelian microsatellite loci for the Caribbean coral Acropora palmata. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 288:115–127

Baums IB, Miller MW, Hellberg ME (2005b) Regionally isolated populations of an imperiled Caribbean coral, Acropora palmata. Mol Ecol 14:1377–1390

Baums IB, Miller MW, Hellberg ME (2006) Geographic variation in clonal structure in a reef-building Caribbean coral, Acropora palmata. Ecol Monogr 76:503–519

Baums IB, Devlin-Durante MK, Polato NR, Xu D, Giri S, Altman NS, Ruiz D, Parkinson JE, Boulay JN (2013) Genotypic variation influences reproductive success and thermal stress tolerance in the reef building coral, Acropora palmata. Coral Reefs 32:703–717

Bellwood DR, Hughes TP, Folke C, Nystrom M (2004) Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature 429:827–833

Brown-Saracino C, Peckol P, Curran HA, Robbart ML (2007) Spatial variation in sea urchins, fish predators, and bioerosion rates on coral reefs of Belize. Coral Reefs 26:71–78

Budd AF, Stemann TA, Johnson KG (1994) Stratigraphic distributions of genera and species of Neogene to recent Caribbean reef corals. J Paleontol 68:951–957

Busch J, Greer L, Harbor D, Wirth K, Lescinsky H, Curran HA (2016) Quantifying unusually large populations of Acropora spp. corals in Belize using sub-meter multispectral satellite imagery classification. Bull Mar Sci 92:265–283

Carvalho GR (1994) Genetics of aquatic clonal organisms. In: Beaumont AR (ed) Genetics and evolution of aquatic organisms. Chapman and Hall, London, pp 291–323

Devlin-Durante MK, Miller MW, Caribbean Acropora Research, Precht WF, Baums IB (2016) How old are you? Genet age estimates in a clonal animal. Mol Ecol 25:5628–5646

de Witte LC, Stocklin J (2010) Longevity of clonal plants: why it matters and how to measure it. AoB Plants 106:859–870

Downing A, van Nes E, Mooij WM, Scheffer M (2012) The resilience and resistance of an ecosystem to a collapse of diversity. PLoS One 7:e46135

Eakin CM, Morgan JA, Heron SF, Smith TB, Liu G, Alvarez-Filip L, Baca B, Bartels E, Bastidas C, Boucon C, Brandt M, Bruckner AW, Bunkley-Williams L, Cameron A, Causey BD, Chiappone M, Christensen TRL, Crabbe MJC, Day O, Guardia E, Diaz-Pulido G, DiResta D, Gil-Agudelo DL, Gilliam DS, Ginsburg RN, Gore S, Guzman HM, Hendee JC, Hernandez-Delgado EA, HusainE Jeffrey CFG, Jones RJ, Jordan-Dahlgren E, Kaufman LS, Kline DI, Kramer PA, Lang JC, Lirman D, Mallela J, Manfrino C, Marechal JP, Marks K, Mihaly J, Miller WJ, Mueller EM, Muller EM, Toro CAO, Oxenford HA, Ponce-Taylor D, Quinn N, Ritchie KB, Rodriguez S, Ramirez AR, Romano S, Samhouri JF, Sanchez JA, Schmal GP, Shank BV, Skirving WJ, Steiner SCC, Villamizar E, Walsh SM, Walter C, Weil E, Williams EH, Roberson KW, Yusuf Y (2010) Caribbean corals in crisis: record thermal stress, bleaching, and mortality in 2005. PLoS One 5:e13969

Eriksson O (2000) Functional roles of remnant plant populations in communities and ecosystems. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 9:443–449

Fogarty ND (2010) Reproductive isolation and hybridization dynamics in threatened Caribbean acroporid corals. PhD thesis, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

Fogarty ND (2012) Caribbean acroporid coral hybrids are viable across life history stages. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 446:145–159

Fogarty ND, Vollmer SV, Levitan DR (2012) Weak prezygotic isolating mechanisms in threatened Caribbean Acropora corals. PLoS One 7:e30486

Garcia MB, Pico FX, Ehrlen J (2008) Life span correlates with population dynamics in perennial herbaceous plants. Am J Bot 95:258–262

Gardner TA, Cote IM, Gill JA, Grant A, Watkinson AR (2003) Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. Science 301:958–960

Gladfelter WB (1982) White-band disease in Acropora palmata: implications for the structure and growth of shallow reefs. Bull Mar Sci 32:639–643

Harper JL (1977) Population biology of plants. Academic Press, London

Highsmith RC (1982) Reproduction by fragmentation in corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 7:207–226

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Mumby PJ, Hooten AJ, Steneck RS, Greenfield P, Gomez E, Harvell CD, Sale PF, Edwards AJ, Caldeira K, Knowlton N, Eakin CM, Iglesias-Prieto R, Muthiga N, Bradbury RH, Dubi A, Hatziolos ME (2007) Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318:1737–1742

Hughes RN (1989) A functional biology of clonal animals. Chapman and Hall, London and New York

Hughes TP (1994) Catastrophes, phase shifts, and large-scale degradation of a Caribbean coral reef. Science 265:1547–1551

Hughes TP, Baird AH, Bellwood DR, Card M, Connolly SR, Folke C, Grosberg R, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Jackson JBC, Kleypas J, Lough JM, Marshall P, Nystrom M, Palumbi SR, Pandolfi JM, Rosen B, Roughgarden J (2003) Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 301:929–933

Japaud A, Fauvelot C, Bouchon C (2014) Unexpected high densities of the hybrid coral Acropora prolifera (Lamarck 1816) in Guadeloupe Island, Lesser Antilles. Coral Reefs 33:593

Kays S, Harper JL (1974) The regulation of plant and tiller density in a grass sward. J Ecol 63:97–105

Keck J, Houston RS, Purkis S, Riegl BM (2005) Unexpectedly high cover of Acropora cervicornis on offshore reefs in Roatán (Honduras). Coral Reefs 24:509

Keppel G, Val Niel KP, Wardell-Johnson GW, Yates CJ, Byrne M, Mucina L, Schut AGT, Hopper SD, Franklin SE (2012) Refugia: identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 21:393–404

Kuffner IB, Lidz BH, Hudson JH, Anderson JS (2015) A century of ocean warming on Florida Keys coral reefs: historic in situ observations. Estuaries and Coasts 38:1085–1096

Lang JC, Alcolando P, Carricart-Ganivet JP, Chippone M, Curran A (1998) Status of coral reefs in the northern areas of the wider Caribbean. In: Wilkinson CR (ed) Status of coral reefs of the world: 1998. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, pp 123–134

Larson EA, Gilliam DS, Padierna ML, Walker BK (2014) Possible recovery of Acropora palmata (Scleractinia: Acroporidae) within the Veracruz Reef System, Gulf of Mexico: a survey of 24 reefs to assess the benthic communities. Rev Biol Trop 62:75–84

Levitan DR, McGovern TM (2005) The Allee effect in the sea. In: Norse EA, Crowder IB (eds) Marine conservation biology: the science of maintaining the sea’s biodiversity. Island Press, Washington DC, pp 47–57

Lirman D (2000) Fragmentation in the branching coral Acropora palmata (Lamarck): growth, survivorship, and reproduction of colonies and fragments. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 25:41–57

Lirman D, Bowden-Kerby A, Schopmeyer S, Huntington B, Thyberg T, Gough M, Gough T, Gough R, Gough Y (2010) A window to the past: documenting the status of one of the last remaining ‘megapopulations’ of the threatened staghorn coral Acropora cervicornis in the Dominican Republic. Aquat Conserv 20:773–781

Loarie SR, Carter BE, Hayhoe K, McMahon S, Moe R, Knight CA, Ackerly DD (2008) Climate change and the future of California’s endemic flora. PLoS One 3:e2502

Macintyre IG, Toscano MA (2007) The elkhorn coral Acropora palmata is coming back to the Belize Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs 26:757

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) (2005) Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants: 12-month finding on a petition to list elkhorn coral, staghorn coral, and fused-staghorn coral as threatened or endangered. Code Fed Regul 70:13151–13152

Noss RF (2001) Beyond Kyoto: forest management in a time of rapid climate change. Conserv Biol 15:578–590

Pandolfi J (2002) Coral community dynamics at multiple scales. Coral Reefs 21:13–23

Peckol PM, Curran HA, Floyd EY, Robbart ML, Greenstein BJ, Buckman KL (2003) Assessment of selected reef sites in northern and southern-central Belize, including recovery from bleaching and hurricane disturbances (stony corals, algae and fish). Atoll Res Bull 496:146–171

Purkis SJ, Myint SW, Riegl BM (2006) Enhanced detection of the coral Acropora cervicornis from satellite imagery using a textural operator. Remote Sens Environ 101:82–94

Randall CJ, van Woesik R (2015) Contemporary white-band disease in Caribbean corals driven by climate change. Nat Clim Chang 5:375–379

Reed DH, Frankham R (2003) Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity. Conserv Biol 17:230–237

Reusch TBH, Ehlers A, Hammerli A, Worm B (2005) Ecosystem recovery after climatic extremes enhanced by genotypic diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2826–2931

Richards ZT, Hobbs JPA (2015) Hybridisation on coral reefs and the conservation of evolutionary novelty. Curr Zool 61:132–145

Riegl B, Purkis SJ, Keck J, Rowlands GP (2009) Monitored and modeled coral population dynamics and the refuge concept. Mar Pollut Bull 58:24–38

Schmid B (1994) Effects of genetic diversity in experimental stands of Solidago altissima: evidence for the potential role of pathogens as selective agents in plant populations. J Ecol 82:165–175

Slatkin M (1996) Gene genealogies within mutant allelic classes. Genetics 143:579–587

Steinger T, Korner C, Schmid B (1996) Long-term persistence in a changing climate: DNA analysis suggest very old ages of Alpine Carex curvula. Oecologia 105:94–99

Stenberg P, Lundmark M, Saura A (2003) MLGsim: a program for detecting clones using a simulation approach. Mol Ecol Notes 3:329–331

Szmant AM (1986) Reproductive ecology of Caribbean reef corals. Coral Reefs 5:43–53

Stoddart JA, Taylor JF (1988) Genotypic diversity: estimation and prediction in samples. Genetics 118:705–711

Taberlet P, Cheddadi R (2002) Quaternary refugia and persistence of biodiversity. Science 297:2009–2010

van Oppen MJH, Willis BL, Van Vugt H, Miller DJ (2000) Examination of species boundaries in the Acropora cervicornis group (Scleractinia, Cnidaria) using nuclear DNA sequence analyses. Mol Ecol 9:1363–1373

Vargas-Angel B, Thomas JD, Hoke SM (2003) High-latitude Acropora cervicornis thickets off Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA. Coral Reefs 22:464–473

Vollmer SV, Palumbi SR (2002) Hybridization and the evolution of reef coral diversity. Science 296:2023–2025

Weiher E, van der Werf A, Thompson K, Roderick M, Garnier E, Eriksson O (1999) Challenging Theophrastus: a common core list of plant traits for functional ecology. Journal of Vegetation Science 10:609–620

Wheaton J, Callahan M, Brooke S, Beaver C, Wade S, Johnson D, Kupfner S, Kidney J, Bertin M (2006) Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO) long-term monitoring and assessment project. Annual report 2005–2006. Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, St. Petersburg, FL

Williams DE, Miller MW, Kramer KL (2008) Recruitment failure in Florida Keys Acropora palmata, a threatened Caribbean coral. Coral Reefs 27:697–705

Williams DE, Miller MW, Baums IB (2014) Cryptic changes in the genetic structure of a highly clonal coral population and the relationship with ecological performance. Coral Reefs 33:595–606

Willis BL, van Oppen MJH, Miller DJ, Vollmer SJ, Ayre DJ (2006) The role of hybridization in the evolution of reef corals. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 37:489–517

Zubillaga AL, Marquez LM, Croquer A, Bastidas C (2008) Ecological and genetic data indicate recovery of the endangered coral Acropora palmata in Los Roques, Southern Caribbean. Coral Reefs 27:63–72

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. NSF-REU #1358987 to LG, OCE-1537959 to IB, and the Keck Geology Consortium, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute through the Precollege and Undergraduate Science Education Program, as well as the Washington and Lee University Department of Geology, Office of the Provost, Johnson Opportunity Grant, and the Evans Fund for International Student Experiences to AI and LG. We wish to thank Kelly Bezold for laboratory work as well as Ken Mattes and Maureen Gannon at Belize Marine TREC for logistical support of this project. We are grateful for the support of the Belize Fisheries Department and Mr. James Azueta of the Belize Ecosystems Management Unit and Mr. Miguel Alamilla of the Hol Chan Marine Reserve for research permits to facilitate this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Biology Editor Dr. Line K. Bay

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Irwin, A., Greer, L., Humston, R. et al. Age and intraspecific diversity of resilient Acropora communities in Belize. Coral Reefs 36, 1111–1120 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-017-1602-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-017-1602-9