Abstract

To measure the burden caused by hip fracture in Iran and to compare it with other parts of the world, we applied the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) method created by the World Health Organization. The GBD method uses disability-adjusted life years (DALY), which is comprised of years of life lost (YLL) and years of life lived with disability (YLD). To calculate YLD, incidence of hip fracture was obtained from the Iranian Multicenter Study on Accidental Injuries, a large-scale nationwide prospective study. Disability weights were applied to the remaining duration of disease. To calculate YLL, remaining years of potential life at any age at death were calculated using the standard life table. A discount rate of 3% and age weighting were applied. Hip fracture generated 16,708 DALYs, comprising 8,812 (52.7%) YLL and 7,896 (47.3%) YLD. Iran accounted for 0.85% of the global burden of hip fracture and 12.4% of the burden of hip fracture in the Middle East. The female to male ratio in Iran (1.1) was lower than the global (2.2) and the Middle Eastern (1.4) ratios and higher than the ratios in China and India (1.0 and 0.9, respectively). In conclusion, hip fracture is not as much a cause of disease burden in Iran as in the developed regions of the world. We recommend utilization of the standardized GBD method to calculate burden of osteoporosis in different countries and to set local priorities according to these measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Melton LJ 3rd (1996) Epidemiology of hip fractures: implications of the exponential increase with age. Bone 18:121S–125S

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, de Laet C, Dawson A (2001) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12:417–427

Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ 3rd (1992) Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int 2:285–289

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA (1997) World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 7:407–413

Melton LJ 3rd (1993) Hip fractures: a worldwide problem today and tomorrow. Bone 1:S1–S8

Ray NF, Chan JK, Thamer M, Melton LJ 3rd (1997) Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. J Bone Miner Res 12:24–35

Reginster JY, Gillet P, Ben Sedrine W, Brands G, Ethgen O, de Froidmont C, Gosset C (1999) Direct costs of hip fractures in patients over 60 years of age in Belgium. Pharmacoeconomics 15:507–514

Lippuner K, von Overbeck J, Perrelet R, Bosshard H, Jaeger P (1997) Incidence and direct medical costs of hospitalizations due to osteoporotic fractures in Switzerland. Osteoporos Int 7:414–425

Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds) (1996) The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Global Burden of Disease and Injury Series, vol 1. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Murray CJ (1994) Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ 72:429–445

Murray CJ, Acharya AK (1997) Understanding DALYs disability-adjusted life years. J Health Econ 16:703–730

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2004) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:897–902

Coale A, Guo G (1989) Revised regional model life tables at very low levels of mortality. Popul Index 55:613–643

Malek Afzali H (1998) The life expectancy of Iranian men and women in 1996. Hakim Res J 2:107–110

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby AK (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32:468–473

Moayyeri A, Soltani A, Larijani B, Naghavi M, Alaeddini F, Abolhassani F (2006) Epidemiology of hip fracture in Iran: Results from the Iranian Multicenter Study on Accidental Injuries (IMSAI). Osteoporos Int 17:1252–1257

Mathers CD, Vos T, Lopez AD, Salomon J, Ezzati M (2001) Disease modeling using DISMOD. In: National Burden of Disease Studies: A Practical Guide, ed 2.0, Global Program on Evidence for Health Policy. World Health Organization, Geneva, chap 64

Nord E (1995) The person-trade-off approach to valuing health care programs. Med Decis Making 15:201–208

National Osteoporosis Foundation (1998) Osteoporosis: review of the evidence for prevention, diagnosis and treatment and cost-effectiveness analysis. Osteoporos Int 8:S1–S88

Williams A (1999) Calculating the global burden of disease: time for a strategic reappraisal? Health Econ 8:1–8

Johnell O, Borgstrom F, Jonsson B, Kanis J (2006) Latitude, socioeconomic prosperity, mobile phones and hip fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 18:333–337

Murray CJ, Lopez AD (1997) Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 17:1436–1442

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran. We thank Dr. A. Soltani, Dr. F. Alaeddini, Dr. H. Tavakoli Shalmani, and Dr. N. Jafari for their personal assistance in collecting and analyzing the data. Special thanks are extended to the personnel of the Research Council of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education and all health officials who helped us in conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

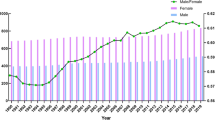

To calculate the number of deaths associated with hip fracture, the following template was applied. As an example, for females at the age of 52, estimated number of deaths among current 52-year-old women experiencing hip fracture this year was summed with the number of deaths of those experiencing hip fracture last year at the age of 51 dying 1 year after fracture and those experiencing hip fracture 2 years ago at the age of 50 dying 2 years after fracture. The appropriate age- and sex-specific mortality rates for each year following fracture were applied to the number of incident hip fractures in Iran for that age and sex after subtracting the estimated number of deaths of the previous years. The proportional excess death after hip fracture (compared to the general population of Sweden) was applied to the mortality rate of the Iranian general population to attain an estimate of the Iranian mortality rate after hip fracture for each age and sex [12, 15]. It was assumed that the proportional excess mortality in Iran was similar to that of Sweden (for each age and sex it was assumed that hip fracture mortality/mortality of the general population for Iran = hip fracture mortality/mortality of the general population for Sweden). For instance, the mortality rate for Iranian patients at the age of 52, two years after a hip fracture was calculated as d = (c/a) * b, as depicted in Figure 1.

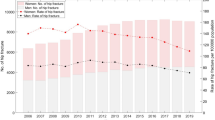

To calculate the number of deaths after hip fracture, the age and sex specific mortality rate for each year following fracture was applied to the estimated number of incident hip fractures for that age and sex after subtracting the estimated number of deaths of the previous year (Fig. 2).

Mortality rates (per 1,000) for the years following a hip fracture occurring at ages 50, 51, and 52 years and the general population.

The following template was used to calculate the number of deaths for all ages and continued until the maximum expected life expectancy.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmadi-Abhari, S., Moayyeri, A. & Abolhassani, F. Burden of Hip Fracture in Iran. Calcif Tissue Int 80, 147–153 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-006-0242-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-006-0242-9