Abstract

Many countries, in an effort to address the problem that many retirees have too little saved up, impose mandatory contributions into retirement accounts, that too, in an age-independent manner. This is puzzling because such funded pension schemes effectively mandate the young, the natural borrowers, to save for retirement. Further, present-biased agents disagree with the intent of such schemes and attempt to undo them by reducing their own saving or even borrowing against retirement wealth. We establish a welfare case for mandating the middle-aged and the young to contribute to their retirement accounts, even with age-independent contribution rates. We find, somewhat counterintuitively, that even though the young responds by borrowing more, that too at a rate higher than offered by pension savings, their lifetime utility increases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It has been documented that, among Americans 40–45 years of age, the median retirement account balance is just $14,500—less than 4% of what the median-income worker will require in savings to meet his retirement needs. (Ghilarducci and James 2018). Gillers et al. (2018) cite a Wall Street Journal analysis that finds “more than 40 percent of households headed by people aged 55 through 70 lack sufficient resources to maintain their living standard in retirement.”

Recent work by Aguiar and Hurst (2013) challenges “retirement-consumption” puzzle and shows that the decline in consumption at retirement belies important heterogeneity across different types of consumption goods—a large part of the consumption decline at retirement is driven by declines in food and work-related expenses suggesting agents substitute away from market expenditures toward household production as the opportunity cost of time declines post retirement. See Olafsson and Pagel (2018) for an updated take on this puzzle. Our analysis is not about this puzzle. If anything, it suggests how government initiatives may prevent any consumption declines.

Myopia means the agent places less weight on the future than his true preferences does. Time-inconsistent preferences imply preference reversal: the relative weight placed by the current self on current versus future utility changes as the life cycle proceeds.

Goda et al. (2015) present evidence on the ubiquity of present-biasedness (roughly, 55%) seen in Americans. They also find a robust negative relationship between retirement savings and the extent of present bias.

Many countries (Australia, Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Mexico, Norway, Poland, Singapore, and many others) have mandatory pension schemes, either mandated by law or via labor market negotiations or contracts, requiring individuals to contribute a certain fraction of their income during their entire work career toward their own retirement. (OECD 2015). These range from 6% in New Zealand to 33% in Italy, once employer and employee mandates are added up. The contribution rates are typically age-independent, and are, therefore, the same for the young, the middle-aged and those close to retirement. One exception is Switzerland which has employee pension contribution rates increasing with age (four age groups) rising from 7% for individual in the age group 25–34 to 18% for the age group 55–65 (55–64 for women). Bateman et al. (2001) contains a detailed review of mandatory saving schemes across OECD countries.

See Fig. 3.2 in Coeurdacier et al. (2015) for data on the USA

The agents at the zero savings corner look a lot like the hand-to-mouth consumers in Kaplan et al. (2014) who “spend all of their available resources in every pay period.” To avoid discontinuities, Findley and Caliendo (2016) “smooth” away the interest rate spread. This allows them to stay away from zero-saving corners. In other words, the agents in their model cannot be “passive” in the sense of Chetty et al. (2014) as each one of them would actively respond to changes in the policy.

Cremer and Pestieau (2011) consider a PAYG scheme in a two-period model with homogeneous agents where, in the absence of a no-borrowing constraint, there is no welfare case for such pensions. Their concern is more about redistribution via a PAYG scheme (seen most clearly, in the case where all agents are non-myopic) and not about whether such schemes solve the present-bias problem.

One interpretation of “passive savers” is that they behave like agents at the zero-saving corner alluded to above; there may be other interpretations. It bears emphasis that when we say the zero-saving corner, we have in mind zero savings for life-cycle purposes. These people may have positive levels of savings for other reasons. Chetty et al. (2014) stay away from these nitty-gritties.

In an online working paper version, we allow \(R_{b}\) to depend on the amount borrowed. That is, if s is the amount saved, then

$$\begin{aligned} R(s)=\left\{ \begin{array}[c]{l} R\quad \text { for }s\ge 0\\ R(s)>R\quad \text { for }s<0,\;R^{\prime }(s)>0 \end{array} \right. . \end{aligned}$$The government is assumed to pre-commit to these contribution rates. For an insightful analysis of these issues in the absence of such precommittment, see Findley and Caliendo (2015).

To make voluntary and mandatory savings non-perfect substitutes, Gale and Scholz (1994) presents a three-period OLG model with income uncertainty in period 2. This creates a legitimate precautionary demand for saving that mandated pensions do not satisfy. Chetty et al. (2014) introduce a specific utility gain from the flexibility available with voluntary saving. This is discussed in the online working paper version.

In reality, it may be that pension wealth is not accepted as collateral by lenders. We touch on this below.

The alternative case has so-called naive myopics, who do not perceive the upcoming change in their preferences. In an online working paper version, we briefly consider this case and argue that results remain unchanged qualitatively.

As an online working paper makes clear, if \(R_{b}\) is permitted to smoothly vary with borrowing (and is equal to R at zero borrowing), then the corner is removed; all our results go through in this case.

Of course, if \(\tau _{y}=\tau _{m}=0\), the middle-aged will save at any R to ensure some consumption when old.

Also, as mentioned in the introduction, the zero retirement saving corner refers to zero voluntary saving for retirement purely due to a life-cycle motive. The online working paper makes clear that our results go through even if other motives for saving, such as a need for flexibility (as in Chetty et al. 2014) are included, in which case there would be positive voluntary saving on net but none for life-cycle reasons.

Obviously, this holds for \(w_{y}=0\). However, we need a positive wage income for Self 1so as to be able to pose the question, does it make sense for the young to be mandated to save for pensions.

The different saving decisions of the middle-aged under choice and true preferences is because \({\widetilde{\delta }}\ne \) \(\delta ^{*}\). The borrowing decisions when young are also different, not only because \({\widetilde{\delta }}\ne \) \(\delta ^{*}\) but also the sophisticated young under choice preferences is cognizant that his middle-aged self will attempt to undo his action, a concern the young under true preferences does not have to contend with.

In the limit, letting \(R_{b}\rightarrow \infty \) (no borrowing allowed, as in most of the literature discussed in the introduction) eliminates borrowing. In that case, the optimal saving level can always be implemented.

Guo and Caliendo (2014) argue that a time-inconsistent mandated saving policy, one which deviates from the stated \(\left( \tau _{y},\tau _{m}\right) \) and “misleads” the middle-aged as to their required contribution rate, may deliver the optimal (\(b_{y}^{*},s_{m}^{*}\)).

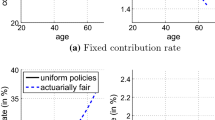

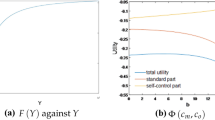

The parameters chosen are \(\delta ^{*}=0.9,\) \(\delta =0.85,\) \(\beta =0.8,\) \(w_{y}=4,\) \(w_{m}=8,\) \(R=1.5,\) and \(R_{b}=1.75.\)

In practice, governments could simply exempt those who can show adequate saving-for-retirement from the scheme.

Caliendo and Findley (2019) study the issue of multiple-self Pareto efficiency and find that much depends on the frequency of choice—if large, as in a full-blown life-cycle model, it is more likely that the commitment allocation is preferred by later selves. It would be interesting—an issue we leave to future research—to compute the possible set of commitment allocations that satisfy multi-self Pareto efficiency.

This was not the case in Andersen and Bhattacharya (2011) where the alternative to private saving was return-dominated unfunded social security. As such, as private capital got crowded out, its return rose, thereby preventing agents from hitting the zero-capital corner. There too, sufficient myopia was needed to get a welfare role for PAYG pensions.

References

Aguiar, M., Hurst, E.: Deconstructing life cycle expenditure. J. Polit. Econ. 121(3), 437–492 (2013)

Alessie, R., Angelini, V., Van Santen, P.: Pension wealth and household savings in Europe: evidence from SHARELIFE. Eur. Econ. Rev. 63, 308–328 (2013)

Andersen, A.L., Christensen, A.M., Nielsen, N. F., Koob, S. A., Oksbjerg, M., Kaarup, R.: Income and debt for families, Danish Central Bank. Q. Rev. 2012.2—part 2, 1–40 (2012)

Andersen, T.M., Bhattacharya, J.: On myopia as rationale for social security. Econ. Theory 47, 135–158 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-010-0528-z

André, C.: Household Debt in OECD Countries: Stylised Facts and Policy Issues, Economics Department WP no. 1277. OECD, Paris (2016)

Attanasio, O.P., Weber, G.: Consumption and saving: models of intertemporal allocation and their implications for public policy. J. Econ. Lit. 48(3), 693–751 (2010)

Basu, K.: A behavioral model of simultaneous borrowing and saving. Oxford Econ. Pap. 68(4), 1166–1174 (2016)

Bateman, H., Kingston, G., Piggott, J.: Forced Saving: Mandating Private Retirement Incomes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2001)

Bernheim, B. D.: Taxation and saving. In: Handbook of Public Economics, vol. 3, pp. 1173–1249. Elsevier, New York (2002)

Blau, D.M.: Pensions, household saving, and welfare: a dynamic analysis of crowd out. Quant. Econ. 7(1), 193–224 (2016)

Caliendo, F.N., Findley, T.S.: Commitment and welfare. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 159, 210–234 (2019)

Chetty, R.: Behavioral economics and public policy: a pragmatic perspective. Am. Econ. Rev. 105(5), 1–33 (2015)

Chetty, R., Friedman, J.N., Leth-Petersen, S., Nielsen, T.H., Olsen, T.: Active vs. passive decisions and crowd-out in retirement savings accounts: evidence from Denmark. Q. J. Econ. 129(3), 1141–1219 (2014)

Coeurdacier, N., Guibuad, S., Keyu, J.: Credit constraints and growth in a global economy. Am. Econ. Rev. 105(9), 2838–2881 (2015)

Cremer, H., Pestieau, P.: Myopia, redistribution and pensions. Eur. Econ. Rev. 55, 165–175 (2011)

Cremer, H., De Donder, P., Maldonado, D., Pestieau, P.: Designing a linear pension scheme with forced savings and wage heterogeneity. Int. Tax Public Finance 15(5), 547–562 (2008)

Danish Ministry for Economic and Interior Affairs: The economic situation for families: distribution, poverty, and incentives. Copenhagen (2014)

Diamond, P.: A framework for social security analysis. J. Public Econ. VIII, 275–298 (1977)

Diamond, P., Köszegi, B.: Quasi-hyperbolic discounting and retirement. J. Public Econ. 87, 1839–1872 (2003)

Eckstein, Z., Eichenbaum, M.S., Peled, D.: Uncertain lifetimes and welfare enhancing properties of annuity markets and social security. J. Public Econ. 26, 303–326 (1985)

Engelhardt, G.V., Kumar, A.: Employer matching and 401 (k) saving: evidence from the health and retirement study. J. Public Econ. 91(10), 1920–1943 (2007)

Engen, E.M., Gale, W.G., Scholz, J.K.: The illusory effects of saving incentives on saving. J. Econ. Perspect. 10(4), 113–138 (1996)

Feldstein, M.: The optimal level of social security benefits. Q. J. Econ. 100(2), 303–320 (1985)

Feldstein, M., Leibman, J.: Social security. In: Auerbach, A., Feldstein, M. (eds.) Chapter 32: Handbook of Public Economics, vol. 4. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2002)

Findley, T.S., Caliendo, F.N.: Time inconsistency and retirement choice. Econ. Lett. 129, 4–8 (2015)

Findley, T.S., Caliendo, F.N.: Time-Inconsistent Preferences, Borrowing Costs, and Social Security. mimeo Utah State University (2016)

Gale, W.G.: The effects of pensions on household wealth: a reevaluation of theory and evidence. J. Polit. Econ. 106(4), 706–723 (1998)

Gale, W.G., Scholz, J.K.: Intergenerational transfers and the accumulation of wealth. J. Econ. Perspect. 8(4), 145–160 (1994)

Ghilarducci, T., James, T.: Americans Haven’t Saved Enough for Retirement. What Are We Going to Do About It? Harvard Business Review (2018)

Gillers, H., Tergessen, A., Scism, L.: A generation of americans is entering old age the least prepared in decades. Wall Street J. (2018)

Goda, G.S., Levy, M., Manchester, C.F., Sojourner, A., Tasoff, J.: The Role of Time Preferences and Exponential-Growth Bias in Retirement Savings (No. 15-04). National Bureau of Economic Research (2015)

Gul, F., Pesendorfer, W.: Temptation and self-control. Econometrica 69(6), 1449–76 (2001)

Gul, F., Pesendorfer, W.: Self-control and the theory of consumption. Econometrica 72, 119–158 (2004)

Guo, N.L., Caliendo, F.N.: Time-inconsistent preferences and time-inconsistent policies. J. Math. Econ. 51, 102–8 (2014)

Hubbard, R.G., Skinner, J.S.: Assessing the effectiveness of saving incentives. J. Econ. Perspect. 10(4), 73–90 (1996)

Imrohoroglu, A., Imrohoroglu, S., Joines, D.H.: Time-inconsistent preferences and social security. Q. J. Econ. 118(2), 745–784 (2003)

Kaplan, G., Violante, G.L.: A model of the consumption response to fiscal stimulus payments. Econometrica 82(4), 1199–1239 (2014)

Kaplan, G., Violante, G.L., Weidner, J.: The wealthy hand-to-mouth. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2014(1), 77–138 (2014)

Kaplow, L.: The Theory of Taxation and Public Economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2008)

Kumru, Ç.S., Thanopoulos, A.C.: Social security and self control preferences. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 32(3), 757–778 (2008)

Laibson, D.: Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Q. J. Econ. 112, 443–77 (1997)

Laibson, D., Repetto, A., Tobacman, J., Hall, R., Gale, W., Akerlof, G.: Self-control and saving for retirement. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 1998(1), 91–196 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-019-01228-1

Lindbeck, A., Persson, M.: The gains from pension reform. J. Econ. Lit. XLI, 74–112 (2003)

Liu, L., Niu, Y., Wang, Y., Yang, J.: Optimal consumption with time-inconsistent preferences. Economic Theory 1–31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-019-01228-1

Luttmer, E., Mariotti, T.: Efficiency and equilibrium when preferences are time-inconsistent. J. Econ. Theory 132(1), 493–506 (2007)

Malin, B.A.: Hyperbolic discounting and uniform savings floors. J. Public Econ. 92, 1986–2002 (2008)

Morduch, J.: Borrowing to save. J. Glob. Dev. 1(2), 1–11 (2010)

Nielsen, C.K.: Rational overconfidence and social security: subjective beliefs, objective welfare. Econ. Theory 65(2), 179–229 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-016-1022-z

O’Donoghue, T., Rabin, M.: Doing it now or later. Am. Econ. Rev. 89(1), 103–24 (1999)

OECD: Improving Financial Education and Awareness on Insurance and Private Pensions. OECD, Paris (2008)

OECD: Pensions at a Glance. OECD, Paris (2015)

Olafsson, A., Pagel, M.: The retirement-consumption puzzle: new evidence from personal finances (No. w24405). National Bureau of Economic Research (2018)

Pestieau, P., Possen, U.: Prodigality and myopia—two rationales for social security. Manch. Sch. Econ. 76(6), 629–652 (2008)

Poterba, J.M.: Retirement security in an aging population. Am. Econ. Rev. 104(5), 1–30 (2014)

Poterba, J., Venti, S.F., Wise, D.A.: How retirement saving programs increase saving. J. Econ. Perspect. 10(4), 91–112 (1996)

St-Amant, P.-A.B., Garon, J.-D.: Optimal redistribitive pensions and the costs of self-control. Int. Tax Public Finance 22, 723–740 (2015)

Statistics Denmark: Statistics on Labour, Income and Wealth (2017). www.statistikbanken.dk, series: Formue7 accessed June 18th 2017)

Summers, L.H.: Some simple economics of mandated benefits. Am. Econ. Rev. 79(2), 177–183 (1989)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The paper has benefitted tremendously from the generous and constructive comments of an anonymous referee. The authors graciously acknowledge financial support from the Danish Council for Independent Research (Social Sciences) under the Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation.

Appendices

Appendix

Borrowing by the young

The savings decision of the middle-aged (\(s_{m}\)) depends on borrowing as young (\(b_{y}\)), and this is perceived by the (sophisticated) young. Hence, the two decisions are interconnected. The main text works with the case where agents in the absence of mandatory pension savings are borrowers as young (\(b_{y}>0\)) and savers as middle-aged (\(s_{m}>0\)), since this is the case where the welfare rationale for mandatory savings (especially for the young) may be called into question. If the young are savers, there is no essential difference between being young and middle-aged.

In the absence of mandatory savings, it is trivial that the middle-aged are saving (\(s_{m}>0\)) since this is the only way of ensuring consumption when old. From the main text—see Eq. (10), we have that

If \(\frac{\partial \Omega }{\partial b_{y}}\mid _{b_{y}=0}>0\) it follows that \(b_{y}>0\) which in turn requires

or using \({\widetilde{\delta }}Ru^{\prime }\left( Rs_{m}\right) =u^{\prime }\left( w_{m}-s_{m}\right) ,\)

Note that \({\widetilde{\delta }}R_{b}-\left( \delta -{\widetilde{\delta }}\right) \frac{\partial s_{m}}{\partial b_{y}}<\delta R_{b}\) since \(\frac{\partial s_{m}}{\partial b_{y}}>-R_{b}\). Thus, a sufficient condition ensuring \(b_{y}>0\) is

where \(s_{m}\) is determined from \(u^{\prime }\left( w_{m}-s_{m}\right) =R{\widetilde{\delta }}u^{\prime }\left( Rs_{m}\right) \); hence \(0<s_{m}<w_{m}\). Hence, condition (18) holds if the wage as young is not too high, i.e.,

Overborrowing by the young and undersaving by the middle-aged

This appendix proves that agents “overborrow” when young (\(b_{y}>b_{y}^{*} \)) and “undersave” when middle-aged (\(s_{m}<s_{m}^{*}\)) in the absence of any pension scheme (\(\tau _{y}=\tau _{m}=0\)). The savings decision of the middle-aged is determined by: \(-u^{\prime }\left( w_{m}-R_{b}b_{y} -s_{m}\right) +{\widetilde{\delta }}Ru^{\prime }\left( Rs_{m}\right) =0\) and since \(u^{\prime }\left( Rs_{m}\right) \rightarrow \infty \) for \(s_{m} \rightarrow 0\), it follows that \(s_{m}>0\). Intuitively, the only way by which the individual can ensure consumption as old is by saving as middle-aged. Under the true preferences we have that savings is determined by \(-u^{\prime }\left( w_{m}-R_{b}b_{y}^{*}-s_{m}^{*}\right) +\delta ^{*} Ru^{\prime }\left( Rs_{m}^{*}\right) =0\). The savings as middle-aged depends on borrowing as young and we have \(s_{m}=\psi (b_{y}),\) \(s_{m}^{*}=\psi ^{*}(b_{y}^{*})\). Notice, that \(\psi (b_{y})<\psi ^{*}(b_{y})\) since \({\widetilde{\delta }}R<\delta ^{*}R\), and both functions are decreasing in their argument.

The first-order condition for the borrowing decision by the young (11)

can by use of \(u^{\prime }(c_{m})={\widetilde{\delta }}Ru^{\prime }\left( c_{o}\right) \) be written

denote the solution by \(b_{y}^{c}\).

For the true preferences, lifetime utility depends on borrowing as young as

Evaluate this derivative, for the borrowing decision of the young under the choice preferences \(b_{y}^{c}\)

Note that the largest possible value of \(-\frac{\partial D\left( b_{y}\right) }{\partial b_{y}}=R_{b}\) which implies

Since \(\psi ^{*}(b_{y})>\psi (b_{y})\Leftrightarrow \) \(u^{\prime }\left( w_{m}-R_{b}b_{y}-\psi (b_{y})\right) <u^{\prime }\left( w_{m}-R_{b}b_{y} -\psi ^{*}(b_{y})\right) ,\) using (21) in (20) yields

It follows \(b_{y}^{*}<b_{y}\) and, therefore, by implication \(s_{m}^{*}>s_{m}\).

Appendix: Age-dependent contribution rates

The following considers whether the young should be mandated to contribute to pension savings, when the middle-aged are doing so (\(\tau _{m}>0\)). To this end, we first need to establish that it is optimal to make the middle-aged contribute, and next consider whether the young should. Similar to above, define \({\underline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\) and \({\overline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\) as the critical contribution rates which delineates the positive savings, savings corner and negative savings for the middle-aged, i.e.,

Case I Middle-aged are saving (\(s_{m}>0\))

When the middle-aged are savers (\(s_{m}>0\)), we have that savings (\(b_{y} ,s_{m}\)) for \(\tau _{y}=0\),\(\tau _{m}>0\) are determined by

This system determines borrowing as young \(b_{y}\) and total savings as middle-aged \(D\equiv s_{m}+\tau _{m}w_{m}\), hence \(\frac{\partial s_{m} }{\partial \tau _{m}}=-w_{m}\) as long as \(s_{m}>0\) holds, and therefore \(\frac{\partial \left( s_{m}+\tau _{m}w_{m}\right) }{\partial \tau _{m}}=0\) which in turn implies \(\frac{\partial b_{y}}{\partial \tau _{m}}=0\). To obtain the comparative statics with respect to \(\tau _{y},\) differentiate each of the optimality conditions above. Tedious algebra shows

from where the signs of \(\frac{\partial b_{y}}{\partial \tau _{y}}\) and \(\frac{\partial s_{m}}{\partial \tau _{y}}\) are established.

Case II Middle-aged at the corner (\(s_{m}=0\))

For \({\underline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\le \tau _{m}\le {\overline{\tau }}_{m}^{a},s_{m}=0\) and a change in the contribution rate for the middle-aged affect true lifetime utility as

Assessing the marginal welfare effect for \(\tau _{m}={\underline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\) using \(u^{\prime }(c_{m})=R{\widetilde{\delta }}u^{\prime }(c_{o})\) we find

i.e., true welfare can be improved by setting a contribution rate \(\tau _{m}>{\underline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\).

Case III Middle-aged as borrowers (\(s_{m}<0\))

Assume that \(\tau _{m}^{*}>{\overline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\) in this case the middle-aged are borrowers. The lifetime utility as perceived when young reads

and the first-order condition reads

by use of \(u^{\prime }\left( c_{m}\right) ={\widetilde{\delta }}R_{b}u^{\prime }\left( c_{o}\right) \) it can be written

where

Note that

implying that \(\frac{\partial s_{m}}{\partial b_{y}}>-R_{b},\) and hence it follows that \(0<\Lambda _{b}<\delta R_{b}R_{b}{\widetilde{\delta }}\). With homothetic preferences \(\Lambda _{a}\) is independent of \(c_{m}\) and \(c_{o} \).

Writing the first-order condition for the borrowing and savings decisions, we have

Differentiating w.r.t \(\tau _{y}\) yields

and w.r.t \(\tau _{m}\)

Writing this in matrix form we have

implying

It follows from the expressions above

Since \(\frac{\partial b_{y}}{\partial \tau _{m}}<0\) it follows that \(-w_{m}-R_{b}\frac{\partial b_{y}}{\partial \tau _{m}}-\frac{\partial s_{m} }{\partial \tau _{m}}<0\) and \(w_{m}R+R_{b}\frac{\partial s_{m}}{\partial \tau _{m}}<0\). Next note

and hence \(\frac{\partial \Omega ^{*}}{\partial \tau _{m}}<0\) for \(\tau _{m}>{\overline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\). This proves the optimal \(\tau _{m}\in \left[ {\underline{\tau }}_{m}^{a},{\overline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\right] \).

1.1 Pension contributions by the young

Assume that the optimal \(\tau _{m}^{*}\in \left[ {\underline{\tau }}_{m} ^{a},{\overline{\tau }}_{m}^{a}\right] .\) Can welfare be improved by setting a \(\tau _{y}>0\)? We have (recall \(s_{m}=0\)) or

Since \(u^{\prime }(c_{y})={\widetilde{\delta }}R_{b}u^{\prime }(c_{m})\) it follows that

and therefore

since \(\frac{\partial b_{y}}{\partial \tau _{y}}<w_{y}\). Hence a sufficient condition that \(\frac{\partial \Omega ^{*}}{\partial \tau _{y}}>0\) is

or

This inequality holds if

For the middle-aged to at the zero savings corner we require

and hence a sufficient condition that \(\frac{\partial \Omega ^{*}}{\partial \tau _{y}}>0\) is

1.2 Implementing (\(b_{y}^{*},s_{m}^{*}\))

Is it possible to implement the optimal choice under the true preferences (\(b_{y}^{*},s_{m}^{*}\))and the associated consumption levels (\(c_{y}^{*},c_{m}^{*},c_{o}^{*}\)) by some choice of \(\tau _{y}\) and \(\tau _{m}\)? To address this question, first write the consumption levels for the optimal choices under the true preferences, i.e.,

and under the choice preference for given values of \(\tau _{y}\) and \(\tau _{m} \).

For \(c_{y}\) \(=c_{y}^{*}\), we require

or

For \(c_{m}=c_{m}^{*}\) we require

or

Finally, for \(c_{o}=c_{o}^{*}\) we require

or

or \(R\tau _{y}w_{y}=R_{b}\left( b_{y}-b_{y}^{*}\right) \) and using (22) this requires \(R\tau _{y}w_{y}=R_{b}\tau _{y}w_{y}\) which cannot hold for \(R<R_{b}\), showing that it is not possible to implement (\(b_{y}^{*},s_{m}^{*}\))and the associated consumption levels (\(c_{y}^{*},c_{m}^{*},c_{o}^{*}\)) by some choice of \(\tau _{y}\) and \(\tau _{m}\).

Age-independent contribution rates

When the middle-aged are savers, savings decisions are determined by

where

Note that \(0<\Lambda _{I}<RR_{b}\delta {\widetilde{\delta }}\) and \(\Lambda _{I} \) is independent of \(b_{y}\) and \(s_{m}\) under homothetic preferences.

Hence, differentiating the optimality conditions above with respect to \(\tau \), we get

implying

To solve for \(\frac{\partial s_{y}}{\partial \tau }\) and\(\frac{\partial s_{m} }{\partial \tau }\) the above expression can be written in matrix form as which implies that

implying

From this, it can be inferred by use of the above sign-relations: \(w_{y} -\frac{\partial b_{y}}{\partial \tau }>0;\) \(w_{m}+R_{b}\frac{\partial b_{y} }{\partial \tau }+\frac{\partial s_{m}}{\partial \tau }>0;\) \(R\frac{\partial s_{m}}{\partial \tau }+R^{2}w_{y}+Rw_{m}<0\). Considering the welfare effects from a change in \(\tau \) we have

and it follows that \(\frac{\partial \Omega ^{*}}{\partial \tau }<0\) for \(\tau <{\underline{\tau }}\).

Consider next \(\tau \in \left[ {\underline{\tau }},{\overline{\tau }}\right] \) where the middle-aged are at a corner. In this case, borrowing as young is determined by

and the corner condition reads

It follows straightforwardly that

Note for later

For \(\tau \in \left[ {\underline{\tau }},{\overline{\tau }}\right] \) and thus \(s_{m}=0\) we have that welfare is affected by a change in the contribution rate as:

evaluated for \({\underline{\tau }}\) and using \(u^{\prime }(c_{m} )={\widetilde{\delta }}Ru^{\prime }(c_{o})\) we get

or

where

Consider the term

Since \(\frac{u^{\prime \prime }\left( c_{y}\right) }{u^{\prime \prime }\left( c_{y}\right) +{\widetilde{\delta }}R_{b}^{2}u^{\prime \prime }\left( c_{m}\right) }<1\) it follows that

Hence, this expression is positive if \(\delta ^{*}R-{\widetilde{\delta }} R_{b}>0\), and it follows that a sufficient condition that\(\frac{\partial \Omega ^{*}}{\partial \tau }\mid _{{\underline{\tau }}}>0\) is \(\delta ^{*}R-{\widetilde{\delta }}R_{b}>0\).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, T.M., Bhattacharya, J. Why mandate young borrowers to contribute to their retirement accounts?. Econ Theory 71, 115–149 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-019-01235-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-019-01235-2