Abstract

Objective

To review the last thirty years of studies that, using Swedish population registers, have added to our understanding of the aetiology of schizophrenia

Sample Included/Methods

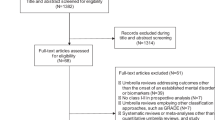

A literature search was performed to systematically review all studies that using Swedish Population based registers have investigated the aetiology of schizophrenia. Key authors in the field, predominately from Swedish institutions, were additionally contacted and key journals hand searched, for missing references. A quality assessment methodological review was then conducted on each study. Data was extracted and tabulated on identified aetiological themes

Results

61 articles were included corresponding to 10 identified aetiological themes. Although the majority of included studies were retrospective cohort studies, case control studies were also included where they used population based registers. Confirming previous research, schizophrenia was found to have a multi-factorial aetiological basis with pregnancy and birth factors, parental age, social adversity, genetics, substance misuse, migration and ethnicity, personality, non-psychiatric co-morbidity, psychiatric history and poor cognitive performance all found to be significantly associated with an increased risk of later schizophrenia.

Conclusions

Although some difficulties exist in analysing the interplay between each of these factors, the Swedish population registers have added considerably to our understanding of each of the presented individual aetiological themes. The ability to study the whole population over several decades has been particularly useful in determining the timing of exposures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Body Mass Index.

References

World Health Organisation (2015) Schizophrenia

Knapp M, Mangalore R, Simon J (2004) The global costs of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull 30(2):279–293

White E, Hunt JR, Casso D (1998) Exposure measurement in cohort studies: the challenges of prospective data collection. Epidemiol Rev 20(1):43–56

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P (2010) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Hultman CM et al (1999) Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for schizophrenia, affective psychosis, and reactive psychosis of early onset: case-control study. BMJ Br Med J 318(7181):421–426

Gunnell D et al (2003) Patterns of fetal and childhood growth and the development of psychosis in young males: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 158(4):291–300

Nilsson E et al (2005) Fetal growth restriction and schizophrenia: a Swedish twin study. Twin Res Hum Genet 8(4):402–408

Abel KM et al (2010) Birth weight, schizophrenia, and adult mental disorder: is risk confined to the smallest babies? Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(9):923–930

Gunnell D et al (2005) The association of fetal and childhood growth with risk of schizophrenia. Cohort study of 720,000 Swedish men and women. Schizophrenia Res 79(2):315–322

Nosarti C et al (2012) Preterm birth and psychiatric disorders in young adult life. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(6):610–617

Dalman C et al (1999) Obstetric complications and the risk of schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of a national birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56(3):234–240

Gunawardana L et al (2011) Pre-conception inter-pregnancy interval and risk of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 199(4):338–339

Fouskakis D et al (2004) Is the season of birth association with psychosis due to seasonal variations in foetal growth or other related exposures? a cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109(4):259–263

Svensson E et al (2013) Schizophrenia susceptibility and age of diagnosis—a frailty approach. Schizophrenia Res 147(1):140–146

Karlsson H et al (2012) Maternal antibodies to dietary antigens and risk for nonaffective psychosis in offspring. Am J Psychiatry 169(6):625–632

Class QA et al (2014) Offspring psychopathology following preconception, prenatal and postnatal maternal bereavement stress. Psychol Med 44(1):71–84

Stalberg K et al (2007) Prenatal ultrasound scanning and the risk of schizophrenia and other psychoses. Epidemiology 18(5):577–582

Dalman C et al (2001) Signs of asphyxia at birth and risk of schizophrenia. Population-based case-control study. Br J Psychiatry 179:403–408

Dalman C, Allebeck P (2002) Paternal age and schizophrenia: further support for an association. Am J Psychiatry 159(9):1591–1592

Zammit S et al (2003) Paternal age and risk for schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 183:405–408

Sipos A et al (2004) Paternal age and schizophrenia: a population based cohort study. BMJ 329(7474):22

Frans EM et al (2011) Advanced paternal and grandpaternal age and schizophrenia: a three-generation perspective. Schizophrenia Res 133(1–3):120–124

Svensson AC et al (2012) Familial aggregation of schizophrenia: the moderating effect of age at onset, parental immigration, paternal age and season of birth. Scand J Public Health 40(1):43–50

Ekeus C, Olausso PO, Hjern A (2006) Psychiatric morbidity is related to parental age: a national cohort study. Psychol Med 36(2):269–276

Ek M et al (2014) Advancing paternal age and schizophrenia: the impact of delayed fatherhood. Schizophr Bull: First published online 4 Nov 2014. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu154

Ek M et al (2012) Adoptive paternal age and risk of psychosis in adoptees: a register based cohort study. PLoS ONE 7(10):e47334

Wicks S et al (2005) Social adversity in childhood and the risk of developing psychosis: a national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 162(9):1652–1657

Wicks S, Hjern A, Dalman C (2010) Social risk or genetic liability for psychosis? a study of children born in Sweden and reared by adoptive parents. Am J Psychiatry 167(10):1240–1246

Hjern A, Wicks S (2004) Dalman C (2004) Social adversity contributes to high morbidity in psychoses in immigrants–a national cohort study in two generations of Swedish residents. Psychol Med 34(6):1025–1033

Westman J, Johansson LM, Sundquist K (2006) Country of birth and hospital admission rates for mental disorders: a cohort study of 4.5 million men and women in Sweden. Eur Psychiatry 21(5):307–314

Lewis G et al (1992) Schizophrenia and city life. Lancet 340(8812):137–140

Zammit S et al (2010) Individuals, schools, and neighborhood: a multilevel longitudinal study of variation in incidence of psychotic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(9):914–922

Sariaslan A et al (2014) Does population density and neighborhood deprivation predict schizophrenia? a nationwide Swedish family-based study of 2.4 million individuals. Schizophr Bull, Advance access, published online 22 July 2014: doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu105

Sundquist K et al (2008) Subsequent risk of hospitalization for neuropsychiatric disorders in patients with rheumatic diseases: a nationwide study from Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65(5):501–507

Lichtenstein P et al (2006) Recurrence risks for schizophrenia in a Swedish national cohort. Psychol Med 36(10):1417–1425

Lichtenstein P et al (2009) Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet 373:234–239

Larsson H et al (2013) Risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in relatives of people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry 203:103–106

Ludvigsson JF et al (2007) Coeliac disease and risk of schizophrenia and other psychosis: a general population cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol 42(2):179–185

Cederlöf M et al (2014) The association between Darier disease, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia revisited: a population-based family study. Bipolar disorders

Johansson V et al (2014) Multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders: comorbidity and sibling risk in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Mult Scler 20(14):1881–1891

David A et al (1995) Are there neurological and sensory risk factors for schizophrenia? Schizophr Res 14(3):247–251

Fors A et al (2013) Hearing and speech impairment at age 4 and risk of later non-affective psychosis. Psychol Med 43(10):2067–2076

Zammit S et al (2007) Height and body mass index in young adulthood and risk of schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of 1,347,520 Swedish men. Acta Psychiatr Scand 116(5):378–385

Harrison G et al (2006) Risk of schizophrenia and other non-affective psychosis among individuals exposed to head injury: case control study. Schizophr Res 88(1–3):119–126

Andreasson S et al (1987) Cannabis and schizophrenia. A longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Lancet 2(8574):1483–1486

Andreasson S, Allebeck P, Rydberg U (1989) Schizophrenia in users and nonusers of cannabis. A longitudinal study in Stockholm County. Acta Psychiatr Scand 79(5):505–510

Allebeck P et al (1993) Cannabis and schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of cases treated in Stockholm County. Acta Psychiatr Scand 88(1):21–24

Zammit S et al (2002) Self-reported cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia in Swedish conscripts of 1969: historical cohort study. BMJ 325(7374):1199

Manrique-Garcia E et al (2012) Cannabis, schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses: 35 years of follow-up of a population-based cohort. Psychol Med 42(6):1321–1328

Giordano GN et al (2015) The association between cannabis abuse and subsequent schizophrenia: a Swedish national co-relative control study. Psychol Med 45(02):407–414

Andreasson S, Allebeck P (1991) Alcohol and psychiatric illness: longitudinal study of psychiatric admissions in a cohort of Swedish conscripts. Int J Addict 26(6):713–728

Lewis G et al (2000) Non-psychotic psychiatric disorder and subsequent risk of schizophrenia. Cohort study. Br J Psychiatry 177:416–420

Giordano GN et al (2014) The association between cannabis abuse and subsequent schizophrenia: a Swedish national co-relative control study. Psychol Med 3:1–8 (online)

Harrison G et al (2003) Association between psychotic disorder and urban place of birth is not mediated by obstetric complications or childhood socio-economic position: a cohort study. Psychol Med 33(4):723–731

Leao TS et al (2006) Incidence of schizophrenia or other psychoses in first- and second-generation immigrants: a national cohort study. J Nerv Ment Dis 194(1):27–33

Malmberg A et al (1998) Premorbid adjustment and personality in people with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 172:308–313

Zammit S et al (2010) Examining interactions between risk factors for psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 197(3):207–211

Song J et al (2014) Bipolar disorder and its relation to major psychiatric disorders: a family-based study in the Swedish population. Bipolar Disord 13(10):12242

Zammit S et al (2004) A longitudinal study of premorbid IQ Score and risk of developing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, and other nonaffective psychoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61(4):354–360

David AS et al (1997) IQ and risk for schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study. Psychol Med 27(06):1311–1323

Gunnell D et al (2002) Associations between premorbid intellectual performance, early-life exposures and early-onset schizophrenia. Cohort study. Br J Psychiatry 181:298–305

MacCabe JH, Lambe MP, Cnattingius S, Torrång A, Björk C, Sham PC, David AS, Murray RM, Hultman CM (2008) Scholastic achievement at age 16 and risk of schizophrenia and other psychoses: a national cohort study. Psychol Med 38(8):1133–1140

MacCabe JH et al (2013) Decline in cognitive performance between ages 13 and 18 years and the risk for psychosis in adulthood: a Swedish longitudinal cohort study in males. JAMA Psychiatry 70(3):261–270

Dalman C et al (2002) Young cases of schizophrenia identified in a national inpatient register. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol 37(11):527–531

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harper, S., Towers-Evans, H. & MacCabe, J. The aetiology of schizophrenia: what have the Swedish Medical Registers taught us?. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50, 1471–1479 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1081-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1081-7