Abstract

Background

Decades of persuasive messages have reinforced the importance of traditional screening mammography at regular intervals. A potential new paradigm, risk-based screening, adjusts mammography frequency based on a woman’s estimated breast cancer risk in order to maximize mortality reduction while minimizing false positives and overdiagnosis. Women’s views of risk-based screening are unknown.

Objective

To explore women’s views and personal acceptability of a potential risk-based mammography screening paradigm.

Design

Four semi-structured focus group discussions about screening mammography and surveys before provision of information about risk-based screening. We analyzed coded focus group transcripts using a mixed deductive (content analysis) and inductive (grounded theory) approach.

Participants

Convenience sample of 29 women (40–74 years old) with no personal history of breast cancer recruited by print and online media in New Hampshire and Vermont.

Results

Twenty-seven out of 29 women reported having undergone mammography screening. All participants were white and most were highly educated. Some women accepted the idea that early cancer detection with traditional screening was beneficial—although many also reported hearing inconsistent recommendations from clinicians and mixed messages from media reports about mammography. Some women were familiar with a risk-based screening paradigm (primarily related to cervical cancer, n = 8) and thought matching screening mammography frequency to personal risk made sense (n = 8). Personal acceptability of risk-based screening was mixed. Some believed risk-based screening could reduce the harms of false positives and overdiagnosis (n = 7). Others thought screening less often might result in missing a dangerous diagnosis (n = 14). Many (n = 18) expressed concerns about the feasibility of risk-based screening and questioned whether breast cancer risk estimates could be accurate. Some suspected that risk-based mammography was motivated by a desire to save money (n = 6).

Conclusion

Some women thought risk-based screening made sense. Willingness to abandon traditional screening for the new paradigm was mixed. Broad acceptability of risk-based screening will require clearer communication about its rationale and feasibility and consistent messages from the health care team.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

For decades, public health agencies, health care organizations, and patient advocacy groups have sent a clear message to women to convince them of the importance of screening mammography at regular intervals.1, 2 These messages also reinforce the screening imperative: “early detection is the best protection.” Though there are ongoing debates about the age at which to initiate mammography screening and screening intervals, all screening guidelines issued by major organizations (e.g., the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and American Cancer Society) for women with average breast cancer risk recommend routine mammography screening in women aged 50–74 years.3 Moreover, hospitals and clinics routinely send out reminders—or even schedule yearly exams (often without involving a woman’s health care provider)—to maximize compliance with quality measures that are based on those screening guidelines (e.g., the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set assesses women 50–74 years of age who had at least one mammogram in the past 2 years4). Not surprisingly, the majority of women report annual screening.5

Recently, a new paradigm of risk-based screening—adjusting recommendations for when to start and how often to test, based on a woman’s estimated risk of breast cancer—has received increasing attention.3, 6, 7 Mounting evidence documents the harms of screening: frequent false positive results that lead to a cascade of testing, biopsies, anxiety, and overdiagnosis.8,9,10 These harms increase with more frequent screening. While mammography screening reduces breast cancer mortality,10 the absolute benefit is greater for women at higher risk of developing breast cancer. In contrast to a traditional “one-size-fits-all” approach, risk-based screening would personalize recommendations in order to minimize harms and maximize benefits of screening. This would involve tailoring screening initiation and frequency to a woman’s individual risk profile (e.g., age, breast density, genetics, family cancer history) through use of a validated risk model and consideration of women’s preferences (e.g., values and beliefs).3, 11, 12

Currently, there are no guidelines for clinicians on how to evaluate and incorporate patients’ individual breast cancer risks (beyond age) and preferences in shared decision making regarding mammography screening. Implementing risk-based screening may be challenging. Women will be asked to change their routine screening habits, understand the rationale for this new approach, and believe it is in their best interest. In this context, our objective was to explore women’s views of risk-based mammography and the acceptability of this potential screening paradigm.

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study consisting of four semi-structured focus groups. All study materials and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Dartmouth College.

Participant Sampling and Recruitment

We recruited women through local newspaper ads, a listserv, postings on Facebook, and flyers on information bulletin boards in a teaching hospital and several supermarkets in New Hampshire and Vermont. Women interested in participating were eligible if they were 40–74 years old and did not have a history of breast cancer.

Focus Group Procedure

We developed a focus group interview guide to cover: reasons for having screening for breast cancer, knowledge of breast cancer risk factors, perceptions of risk, and reactions to the idea of risk-based screening. One author (KS), an experienced qualitative researcher and focus group facilitator, drafted the focus group guide based on the overall goal to obtain women’s views on the idea of risk-based mammography screening. This guide was then reviewed by three other authors (XH, EO, AT) who are experienced researchers in breast cancer and health services, to ensure relevance of the questions (see Appendix 1). We conducted four focus groups based on guidance for reaching thematic saturation13 and ensured consistency by having all the focus groups conducted by one author (KS). Two additional researchers (EO and HX) were present to assist in facilitation and as note-takers. We obtained verbal informed consent before each session and offered participants a $30 gift card.

At the beginning of each focus group, participants completed a brief written survey about their perceived risk of developing breast cancer and its impact on their screening decisions. We then began the focus group discussion by asking women about their prior mammography experiences, knowledge of breast cancer risk factors, and concepts of breast cancer risk. Women were then asked to read an information sheet that proposed the idea of a risk-based mammography recommendation (Appendix 2) and to discuss their reactions to it. The information sheet included: (1) a list of breast cancer risk factors, (2) current mammography screening recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) screening guidelines which recommend biennial screening mammography for women aged 50–74 years and screening mammography for women prior to age 50 as an individual decision14, (3) concerns about current screening recommendations (e.g., overdiagnosis), and (4) a description of a risk-based screening approach. The risk-based screening approach was described as having women with higher than average breast cancer risk get a mammogram every year and women with lower than average risk get a mammogram every 3 years.

Qualitative Analysis

Each focus group was audiotaped, transcribed, and imported into Dedoose, a qualitative data analysis program.15 Two authors (HX and KS) developed the codebook, themes, and analytic strategy through a mixed deductive (content analysis) and inductive (grounded theory) approach.16 Specifically, we pre-determined some codes based on the multilevel ecological perspective. Previous research on routine mammography screening has shown that screening uptake is influenced by multilevel factors, such as individual demographic and behavioral factors, social relationships (e.g., family recommendation or opposition), community characteristics (e.g., poverty, linguistic isolation, public transportation), health provider/team practice, and state and national policies and guidelines.17,18,19 Understanding the interaction of multilevel factors of influence can enhance the precision of the targeted efforts in cancer control.20, 21 We, therefore, wanted to explore women’s preferences and understanding of tradeoffs between benefits and harms of mammography through this multilevel model that has been shown to be important for communication.22, 23 We then developed additional codes based on an iterative review of the data and emerging themes. The codes were reviewed by the four additional authors and revised to incorporate their feedback.

Disagreements on coding were discussed and resolved through consensus by at least three researchers. The two researchers (HX and KS) then grouped the codes into themes and discussed these with the rest of the research team to reach congruency. Subsequently, themes were further grouped into levels according to the multilevel ecological perspective.24, 25

Results

A total of 29 women without a personal history of breast cancer participated in four focus group sessions. They were all white and had health insurance; most were highly educated; nearly half had a family history of breast cancer and two-thirds reported undergoing annual mammography screening (Table 1).

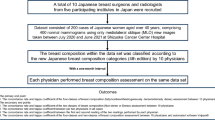

Figure 1 schematically illustrates how we conceptualized the multi-level forces that shape women’s views on risk-based screening. Screening recommendations determine policy, insurance coverage, health care practice patterns, the initiation, and frequency of mammography. They are also the backdrop for external (e.g., breast cancer awareness campaigns and mammography news stories) and personal (e.g., interactions with health care provider/team, family/friends/co-workers, and financial costs) influences on a woman’s beliefs and perceptions about breast cancer risk and the benefits and harms of mammography, which ultimately determines women’s attitudes and acceptability of risk-based screening.

Views of Traditional Screening

Nearly half of the women were confused about current mammography guidelines, including when to start or how often to go (Appendix 3). Few understood why screening guidelines changed (e.g., “You know it’s always changing and we really don’t know what they base it on or what their group is that they’re making those decisions on.”) and some questioned motivations for changes. Flip-flopping news stories (e.g., “I think there’s mixed messages in the media too about how often, what age you should begin. It’s like coffee, today it’s healthy for you, tomorrow it’s not.”) and ineffective doctor-patient communication contributed to this confusion and eroded trust in providers and the medical system (e.g., “I only know that [screening guidelines changes] from the news. It was never communicated to me by my doctor and personally I’m suspicious of the whole medical/industrial complex where it’s all about getting paid a lot of money to use this fancy equipment and that still people don’t, it doesn’t get caught.”).

Factors that appeared to increase desire for mammography at regular intervals included adequate insurance coverage, perceived norms of routine screening, automatic reminders, convenient scheduling, and less painful screening procedures (Appendix 3). Not surprisingly, women who did not have these supports or experiences (e.g., had painful screening experiences) expressed more difficulty in accessing or less desire to have mammograms at regular intervals.

Views on Risk-Based Mammography Screening

Some women were familiar with a risk-based screening paradigm although typically for other cancers (Table 2). For example, one woman said, “so changing the recommendation to a little more high risk versus low risk, to me makes more sense. And you know it’s sort of like the pap smears and stuff. You know they, every year and now it’s every three years, whatever. I think that it’s very individual.”

Despite very limited awareness of this paradigm for breast cancer, some women reported risk-based screening practices (e.g., low-risk women not being screened every year). Some (n = 8) thought the concept of matching screening frequency to personal risk made sense (e.g., “I think that this plan makes sense to me… I think it’s crazy to treat the whole population like we’re all the same and we all have the same risks. We don’t.”).

External and personal influences were similar for traditional and risk-based screening—with the exception of insurance coverage. Insurance appears to encourage screening at whatever interval it covers (e.g., a low-risk women explained, “if my insurance is gonna pay for it…I can’t think of any reason not to go every year.”).

Women’s Acceptability of Risk-Based Mammography Screening

Personal acceptability of risk-based screening was mixed. Some women believed that risk-based screening could reduce the harms of routine screening and seemed willing to reduce screening frequency. Fear and fatigue from false positive results (n = 13) made risk-based screening more appealing (e.g. “I just think there is an awful lot of false positives here… So what do you do? Yeah, it makes me think, like me who say, ‘oh I will go every year’, it makes me pause at that now, … thinking, maybe I’ll go every two years.”).

Others were not very accepting of risk-based screening for themselves. Many (n = 14) were concerned that screening less often might result in missing a dangerous diagnosis (e.g., “I was scared out of my mind when I thought I might have breast cancer, and I probably would still pay for it and go every year.”; “the doctor did say … ‘we don’t need to do this on you until five years’, and I’m like so between now and the next time, I could get cancer, oh well. I’m like, seriously?”). Fear of missing consequential diagnoses outweighed the dislike of false positive results. For some, enthusiasm for routine annual screening was not curbed by the experience of having false positive results—even when it required a biopsy. Others were simply determined to continue their habit of annual mammography (e.g., “I mean I get one every year and so why would I change it now? …everything’s good and why not stay good. So, I’ll just keep going.”).

Many of the participants (n = 18) expressed concerns about the feasibility of estimating personal breast cancer risk. Some questioned whether breast cancer risk estimates were accurate—either because they might not remember personal risk factors (e.g., age of first menses) or because they distrusted or were confused about how risk would be calculated. Some women were skeptical that their providers would adequately explain their risk especially when they believed prior explanations about mammography were inadequate.

Finally, some women (n = 6) raised concerns that risk-based mammography screening was motivated by a desire to save money rather than reduce screening harms. Greater suspicion about motivation was often accompanied by greater determination to continue annual screening (e.g. “…my PCP who I’ve been seeing for years…said to me ...it’s not necessary to have it every year…you start to wonder, well is it anything to do with trying to save money…? Or is it because I’m getting older… I don’t know, so I’ve chosen to continue to have it.”).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to explore women’s views on risk-based mammography screening in the USA. Some women felt risk-based screening made sense. However, willingness to abandon traditional screening for the new paradigm was mixed. Some women valued its ability to reduce the harms of false positives and overdiagnosis. Others were more concerned that less-frequent screening was dangerous. Many expressed concerns about their ability to make sense of their breast cancer risk and whether these estimates would be accurate. Women were skeptical about the motivation for risk-based screening, believing that it was about money rather than reducing screening harms. Skepticism that this paradigm could be implemented was heightened by concerns about poor communication between women and their health care providers.

Our findings are consistent with prior qualitative studies and surveys which found that USPSTF’s updated mammography guidelines recommending less screening had limited impact on women’s screening decisions26, 27 and that women’s familiarity with the concept of overdiagnosis was limited.27,28,29 Our findings were also consistent with prior work finding that women feared underdiagnosis more than overdiagnosis, were suspicious of the underlying reasons for guideline changes, and viewed routine screening as a personal obligation.30, 31 Prior work also shows that women experienced cognitive dissonance when presented with evidence-based mammography information that conflicted with their pre-existing beliefs.32, 33

Our study highlights challenges to offering risk-based screening: the lack of clear communication about guidelines, inconsistent screening recommendations from national bodies and healthcare teams, distrust towards screening guidelines and the healthcare system, and norms promoted by society and personal relationships. For instance, research has shown that even when providers were willing to follow screening guidelines, they sometimes received resistance from their patients or were worried about malpractice.23, 34 Physician specialty also influences recommendations: gynecologists were more likely to recommend mammography screening to younger and older patients than internists and family physicians.35, 36 Guideline inconsistency already exists across major medical groups, including the USPSTF, American Cancer Society, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.37,38,39

At the same time, for women who are already confused by current screening guideline changes, choosing screening frequency based on personal risk may be cognitively overwhelming given lack of information or validated risk-assessment tools.40, 41 Confusion about or resistance to risk-based screening will be exacerbated if there is distrust of doctors and the healthcare industry, which we found in the present study. For instance, some participants questioned if guideline changes and the proposal of risk-based screening (especially the proposal of reducing screening frequency when individual risk is low) were driven by financial concerns rather than scientific evidence, which made them resistant to risk-based screening.25 To better promote risk-based mammography screening, more efforts need to be devoted to building patients’ trust at interpersonal as well as systemic levels.42, 43

Our study has several limitations. Given its exploratory nature and the convenience sample of white, highly educated women, we may not have fully captured the breadth of views on risk-based screening. Women with less formal education and different ethnicities may have additional views that we did not capture. Moreover, women who chose to participate in our focus groups may hold stronger opinions or have greater interest in mammography screening than non-participants. While these focus group findings point to issues that must be addressed for risk-based breast cancer screening to be successfully implemented, future studies among socioeconomically and ethnically diverse women are needed to better understand how women in the USA think about risk-based mammography screening. Fortunately, this study is the foundation for a larger, population-based study of women’s attitudes and perceptions towards risk-based screening that is being developed by the authors. Information gained will help inform how to implement a risk-based screening program.

Broad acceptability of risk-based screening will require clearer interactive communication about its rationale and feasibility supported by consistent messages from the health care team as well as breast cancer awareness campaigns, news stories, and medical organizations. Public health messages, the media, and healthcare professionals need to communicate both the benefits and harms of routine (annual or biennial) screening in a clear and balanced way. Realistic understanding of the benefit and harms is essential prerequisites for communicating risk-based screening.

References

Silverman E, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Byram SJ, Welch HG, Fischhoff B. Women’s Views on Breast Cancer Risk and Screening Mammography: A Qualitative Interview Study. Med Decis Making. 2001;21(3):231–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X0102100308.

Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. The Benefits and Harms of Mammography Screening: Understanding the Trade-offs. JAMA. 2010;303(2):164–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.2007.

Onega T, Beaber EF, Sprague BL, Barlow WE, Haas JS, Tosteson ANA, et al. Breast cancer screening in an era of personalized regimens: A conceptual model and National Cancer Institute initiative for risk-based and preference-based approaches at a population level. Cancer. 2014;120(19):2955–2964. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28771.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016 with Charterbook on Long-term Trends in Health. Hyattsville, MD. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus16.pdf#070. Accessed Feb 3, 2018.

Breast Cancer. (n.d.). Retrieved May 25, 2018, from http://www.ncqa.org/report-cards/health-plans/state-of-health-care-quality/2017-table-of-contents/breast-cancer

Trentham-Dietz A, Kerlikowske K, Stout NK, Miglioretti DL, Schechter CB, Ergun MA , et al. Tailoring Breast Cancer Screening Intervals by Breast Density and Risk for Women Aged 50 Years or Older: Collaborative Modeling of Screening Outcomes. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-0476.

Pace LE, Keating NL. A Systematic Assessment of Benefits and Risks to Guide Breast Cancer Screening Decisions. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1327–1335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.1398.xh

Myers ER, Moorman P, Gierisch JM, Havrilesky LJ, Grimm LJ, Ghate S, et al. Benefits and Harms of Breast Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1615–1634. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.13183.

Spring LM, Marshall MR, Warner ET. Mammography decision making: Trends and predictors of provider communication in the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2011 to 2014. Cancer. 2017;123(3):401–409. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30378

Bleyer A. Screening Mammography. Academic Radiology. 2015;22(8):949–960. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2015.03.003.

Meads C, Ahmed I, Riley RD. A systematic review of breast cancer incidence risk prediction models with meta-analysis of their performance. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(2):365–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1818-2

Cuzick J, Brentnall A, Dowsett M. SNPs for breast cancer risk assessment. Oncotarget 2017;8(59):99211–99212. doi:https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.22278

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Final Recommendation Statement: Breast Cancer: Screening - US Preventive Services Task Force. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/breast-cancer-screening1. Accessed May 23, 2018.

Dedoose Version 7.0.23, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data (2016). Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. Available at www.dedoose.com. Accessed February 6, 2018.

Corbin J, Strauss AL. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage Publications Inc.; 2008.

Akinyemiju TF, Soliman AS, Yassine M, Banerjee M, Schwartz K, Merajver S. Healthcare access and mammography screening in Michigan: a multilevel cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(16). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-16

Coughlin SS, Leadbetter S, Richards T, Sabatino SA. Contextual analysis of breast and cervical cancer screening and factors associated with health care access among United States women, 2002. Soc Sci Med. 2008; 66(2):260–275. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.09.009

Hubbard RA, O’Meara ES, Henderson LM, Henderson LM, Hill D, Braithwaite D, et al. Multilevel factors associated with long-term adherence to screening mammography in older women in the U.S. Prev Med. 2016; 89:169–177. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.034

Rosenberg L, Wise LA, Palmer JR, Horton NJ, Adams-Campbell LL. A multilevel study of socioeconomic predictors of regular mammography use among African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(11): 2628–2633. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0441

McCaffery KJ, Jansen J, Scherer LD, Thornton H, Hersch J, Carter SM, et al. Walking the tightrope: Communicating overdiagnosis in modern healthcare. BMJ 2016;352:I348. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i348

Taplin SH, Price RA, Edwards HM, Edwards HM, Foster MK, Breslau ES, et al. Introduction: Understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;44:2–10. doi: doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs008

Stange KC, Breslau ES, Dietrich AJ, Glasgow RE. State-of-the-art and future directions in multilevel interventions across the cancer control continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;44:20–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs006

Zapka J, Taplin SH, Ganz P, Grunfeld E, Sterba K. Multilevel Factors Affecting Quality: Examples From the Cancer Care Continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):11–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs005.

Allen JD, Bluethmann SM, Sheets M, Opdyke KM, Gates-Ferris K, Hurlbert M, et al. Women’s responses to changes in U.S. preventive task force’s mammography screening guidelines: results of focus groups with ethnically diverse women. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1169.

Kiviniemi MT, Hay JL. Awareness of the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommended changes in mammography screening guidelines, accuracy of awareness, sources of knowledge about recommendations, and attitudes about updated screening guidelines in women ages 40–49 and 50+. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-899.

Ghanouni A, Meisel SF, Renzi C, Wardle J, Waller J. Survey of public definitions of the term “overdiagnosis” in the UK. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010723. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010723.

Moynihan R, Nickel B, Hersch J, Doust J, Barratt A, Beller E, et al. What do you think overdiagnosis means? A qualitative analysis of responses from a national community survey of Australians. BMJ open. 2015;5(5):e007436. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007436

Nagler RH, Franklin Fowler E, Gollust SE. Women’s Awareness of and Responses to Messages About Breast Cancer Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment: Results From a 2016 National Survey. Medical Care. 2017;55(10):879. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000798.

Waller J, Douglas E, Whitaker KL, Wardle J. Women’s responses to information about overdiagnosis in the UK breast cancer screening programme: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):e002703. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002703.

Toledo-Chávarri A, Rué M, Codern-Bové N, Carles-Lavila M, Perestelo-Pérez L, Pérez-Lacasta MJ, et al. A qualitative study on a decision aid for breast cancer screening: Views from women and health professionals. Eur J Cancer Care. 2017;26(3):n/a. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12660.

Henriksen MJV, Guassora AD, Brodersen J. Preconceptions influence women’s perceptions of information on breast cancer screening: a qualitative study. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8:404. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1327-1.

Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press; 1962.

Haas JS, Sprague BL, Klabunde CN, Tosteson ANA, Chen JS, Bitton A, et al. Provider Attitudes and Screening Practices Following Changes in Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. J GEN INTERN MED. 2016;31(1):52–59. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3449-5.

Corbelli J, Borrero S, Bonnema R, McNamara M, Kraemer K, Rubio D, et al. Physician Adherence to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Mammography Guidelines. Women’s Health Issues. 2014;24(3):e313-e319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2014.03.003.

Yasmeen S, Romano PS, Tancredi DJ, Saito NH, Rainwater J, Kravitz RL. Screening mammography beliefs and recommendations: a web-based survey of primary care physicians. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-32.

Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2886

Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R, et al. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk: 2015 Guideline Update From the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12783

Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice Bulletin Number 179: Breast Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening in Average-Risk Women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):e1-e16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002158

Hersch J, Barratt A, Jansen J, et al. Use of a decision aid including information on overdetection to support informed choice about breast cancer screening: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2015;385(9978):1642–1652. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60123-4

Ivlev I, Hickman EN, McDonagh MS, Eden KB. Use of patient decision aids increased younger women’s reluctance to begin screening mammography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J GEN INTERN MED. 2017;32(7):803–812. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4027-9

Yang T-C, Matthews SA, Hillemeier MM. Is health care system distrust a barrier to breast and cervical cancer screening? Evidence from Philadelphia. American journal of public health. 2011;101(7):1297. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300061

Fotaki M. Can consumer choice replace trust in the National Health Service in England? Towards developing an affective psychosocial conception of trust in health care. Sociology of Health & Illness. 36(8):1276–1294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12170

Acknowledgements

We also wish to express our gratitude to the focus group participants who shared their valuable insights and experiences.

Funding

This study was supported in part by funding from the National Cancer Institute (R25CA134286, P01CA154292, and P30CA023108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All study materials and procedures were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College.

Conflicts of interest

Drs. Schwartz and Woloshin have served as medical experts in testosterone litigation and were the cofounders of Informulary, Inc., a company that provided data about the benefits and harms of prescription drugs, which ceased operations in December 2016. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

He, X., Schifferdecker, K.E., Ozanne, E.M. et al. How Do Women View Risk-Based Mammography Screening? A Qualitative Study. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1905–1912 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4601-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4601-9