Abstract

Higher levels of testosterone (T) are thought to promote aggressive and/or antisocial behavior as a means of achieving or maintaining social status. However, recent research has begun to explore the association between T and more prosocial behaviors relevant to social status. Reconciliation after conflict is a prosocial behavior that has become ritualized in sporting contexts. T and cortisol (C) increase in association with athletic competition, but the relationship between these hormones and the willingness to reconcile with one’s opponent after athletic competition has never been tested. Members of a women’s soccer team gave saliva samples associated with two intercollegiate competitions, one victory and one defeat. Samples were subsequently assayed for T and C. Before giving the final saliva sample after each match, participants completed a questionnaire designed to measure willingness to reconcile with a recent opponent – the Attitudes Towards Opponents (ATO) questionnaire. T and C levels increased during competition, but decreased in the 30-min period after the end of play. ATO scores were higher, on average, after the win compared to the loss. ATO scores showed a strong positive correlation with after-game changes in T level in both matches. Win or lose, women whose T remained relatively high after the end of the match were more willing to reconcile with their opponent than women whose T levels declined more precipitously. There were no relationships between C and ATO scores. At least in women, T may motivate after-competition behaviors that promote status through social cohesion rather than overt aggression or dominance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Having social status, power, or dominance over others increases an individual’s access to limited resources and, thus, has noted survival advantages (for review, Cheng et al. 2013; Hamilton et al. 2015). Individuals seeking dominance may do so through various forms of aggression (e.g., Buss and Shackelford 1997; Coie et al. 1982; Vaillancourt and Hymel 2006). However, there are multiple ways other than aggression by which individuals achieve and maintain social status and power including those that may seem prosocial in nature (Cheng et al. 2013; Hawley 1999). Anderson and Kilduff (2009), in review of research on the strategies for status attainment in social groups among humans, highlight the role of making social connections and being cooperative. Specifically, individuals gain status by “enhancing their value in the eyes of fellow group members – that is, by acting in ways that signal task competence, generosity, and commitment” (p.296). Good leaders who possess abundant social influence are often individuals that are well liked (Hogg 2005) and develop positive relationships by being “sensitive, responsive, and caring” towards their followers (Popper 2005, p.47). Accordingly, prosocial behavior may serve as an important pathway to power.

Testosterone (T), a steroid hormone produced in men and in lesser amounts in women, has been linked to social status, implicit power motivation, and behaviors in which social status is contested – being higher in high-status or power-motivated individuals and increasing in response to some laboratory social competitions in winners (for review, Archer 2006; Eisenegger et al. 2011; Hamilton et al. 2015; Mazur and Booth 1998; Stanton and Schultheiss 2009). T also increases substantially over the course of athletic competition seemingly independent of match outcome (e.g., Bateup et al. 2002; Casto et al. 2014; Edwards et al. 2006; Edwards and Kurlander 2010; Gonzalez-Bono et al. 1999; Hamilton et al. 2009; Suay et al. 1999, but see Jiménez et al. 2012). Cortisol (C), a steroid hormone related to physiological and psychological stress, may be inversely related to social status (for review, Hamilton 2015) and increase in response to losing a dominance contest in power-motivated individuals (Wirth et al. 2006). But, C has been shown to increase significantly during athletic competition independent of match outcome (e.g., Bateup et al. 2002; Casto et al. 2014; Edwards et al. 2006; Edwards and Kurlander 2010; Filaire et al. 2009; Gonzalez-Bono et al. 1999). Relatively high levels of C appear to reduce or eliminate the relationship between T and dominance/status seeking behavior in experimental settings (Mehta and Josephs 2010) and T and status relationships among teammates in women athletes (Edwards and Casto 2013). Relatively high baseline C levels also appear to reduce T reactivity to athletic competition (Edwards and Casto 2015) and social stress (Bedgood et al. 2014). Thus, both T and C may be relevant to status-seeking and/or competitive behavior.

Although there are multiple strategies to achieving and maintaining social status, T is perhaps best known for its relationship with aggressive forms of status-seeking (behavior directed towards another with the intent to cause harm; for reviews, see Archer 2006; Book et al. 2001; Carré and Olmstead 2015). However, high levels of T are also associated with high implicit power/dominance motivation and social status in men and (sometimes) in women in the absence of overt aggression (for review, Eisenegger et al. 2011; Stanton and Schultheiss 2009). Recent research has begun to explore the relationship between T and prosocial behaviors that may facilitate social status. Edwards et al. (2006) found that among women athletes, pre-competition levels of T were positively correlated to a self-report measure social-group connectedness among teammates. That social cohesion has benefits for status is consistent with the fact that individual differences in social-group connectedness were also positively related to players’ ranking of leadership abilities by teammates. In an experimental study of prosocial behavior, Eisenegger et al. (2010) gave a single large dose of T to women and asked them to play the ultimatum bargaining game – a laboratory task in which a participant, in the role of proposer, decides how money units should be allocated between herself and a responder who can accept or reject the offer. Participants who were given T made significantly more fair/generous offers than those who were given a placebo. Thus, at least for women, T may preserve status by motivating choices designed to “prevent social affront (Eisenegger et al. 2010, p.358)”. However, Boksem et al. (2013) showed that in a similar game of “trust,” women participants who were given a large dose of T and acting as an “investor” gave significantly less money to an anonymous partner, the trustee, who would decide how much of that investment, tripled, to return. But, when subsequently acting as the trustee, participants who were given the dose of T returned significantly more to the investor when entrusted with a generous offer – a sign of reciprocity. T administration has also been found to increase cooperative behavior in women (only if the second-to-fourth right hand digit ratio indicated low levels of prenatal T exposure; van Honk et al. 2012). Taken together, these studies suggest that, at least in certain contexts, T influences prosocial behavior in women. For men, although some studies have found a link between T administration and behaviors such as reduced lying (Wibral et al. 2012), there is less empirical evidence to support a hypothesized relationship between T and prosocial behavior (e.g., Dabbs and Morris 1990).

Reconciliation, a prosocial post-conflict behavior, is defined as a friendly reunion of former opponents not long after confrontation has occurred (Aureli et al. 2002; de Waal 2000). Reconciliation acknowledges the end of conflict and facilitates the repair of social relationships with a recent adversary (Dovidio et al. 2010). In various non-human socially cohesive primate species, reconciliation after a contest between two or more individuals is common (Aureli et al. 2002) and important for decreasing social tension, preventing future aggressive encounters, and repairing relationships (e.g., Aureli and van Schaik 1991; de Waal 1986; Silk 2002). In one of the few laboratory studies of reconciliation in humans (McCullough et al. 2014), conciliatory gestures increased forgiveness and reduced post-conflict anger and exploitation risk towards a transgressor, provided the relationship with a transgressor was valued. Because reconciliation behaviors reduce the likelihood of post-conflict social reprisals, they may also function more broadly to elevate or maintain social status, but this hypothesis has not been tested empirically. It has, however, been noted in observations of non-human primates that the initiation of post-conflict reconciliation is more common in high status individuals than lower status individuals (de Waal 1984). As indicated in McCullough et al. (2014), “the functional and proximate bases for peacemaking and reconciliation in humans…have been both understudied and under theorized (p. 11,216).”

Athletic competition is a formalized physical and psychological contest to gain status over an opponent. But, ritualized reconciliation behaviors in the form of shaking or slapping hands after sports competitions are intended to foster sportsmanship, that is, fairness, respect, and graciousness in winning and losing, particularly in behaviors towards an opponent. T and C increase substantially over the course of competition and then begin to decline immediately afterwards (e.g., Casto and Edwards 2015; Elias 1981). But the relationship between these changes and after-competition attitudes towards reconciliation has never been tested. The present study was designed to examine the relationship, if any, between basal and dynamic levels of T and C and athletes’ willingness to reconcile with an opponent after competition. The Attitudes Towards Opponents (ATO) questionnaire was specially designed to measure a participant’s attitudes regarding reconciliation with a recent opponent following an athletic competition. T and C levels from saliva samples obtained at pre-warm-up baseline, after warm-up, immediately after competition, and 30 min after each of two intercollegiate soccer matches were analyzed in relation to women athlete’s after-competition responses to the ATO. In contrast to other studies involving the exogenous administration of T and contrived experimental circumstances, in this study, we explore the relationship between prosocial attitudes and endogenous levels of T and C during and after a naturalistic competition – a setting in which women are highly motivated for the social reward of gaining status over their opponent, i.e., winning.

Method

Participants

Participants for the study were the twenty-five consenting members (age 18–22) of the 2013 Emory University varsity women’s soccer team. This research was approved by Emory’s Institutional Review Board and athletes gave written informed consent prior to participation. As part of the consent procedure women were asked to respond “yes” or “no” to the question “Are you currently using an oral contraceptive?” and to one other: “Are you currently using any injected, implanted, or patch-delivered hormone contraceptive?” Of the 25 participants that gave consent, only 17 would go onto play in the first game and 15 in the second game. Because athletes who play have markedly different after-competition levels of T and C than those who never enter the match in this study (Casto and Edwards 2015) and in previous studies (e.g., Edwards et al. 2006), only data for women who played were used in analyses involving hormone values other than baseline.

Saliva Samples and Hormone Assays

As a part of a larger study (Casto and Edwards 2015), participants gave four samples in association with each of two intra-conference NCAA soccer competitions, one week apart. For each match, participants gave a saliva sample 10–15 min before the start of an hour-long warm-up, another sample immediately after warm-up (a few minutes before the start of the match), a third sample immediately after match completion, and a final sample 30 min later. Participants were provided with a piece of sugar-free gum (Trident®, original flavor) to stimulate saliva production and they gave whole saliva samples by drool exactly according to the protocol used for athletes in other sports (e.g., Edwards and Casto 2013). Although the use of chewing gum to stimulate salivation and speed collection of saliva samples is common, this practice has been recently questioned in reports that some brands and flavors of chewing gum may distort salivary T levels relative to unstimulated samples (van Anders 2010). In the present study, all participants chewed Trident® original flavor gum, not tested in the van Anders (2010) study. Provided individuals chew for more than one minute before they begin to deliver the sample, this particular gum does not appear to affect salivary T level relative to what is assayed from unstimulated samples (Dabbs 1991; Granger et al. 2004). All saliva samples were collected between 1 and 5 PM, with both matches beginning around 2:30 PM.

Samples were chilled on ice after collection and then stored at −80 °C within the hour. Samples were assayed in duplicate for T and C on a single thaw by the Biomarkers Core laboratory of the Yerkes Primate Center (Atlanta, GA) using competitive enzyme immunoassay kits from Salimetrics (State College, PA). The average intra-assay CV percents for T and C were 6.1 % and 7.2 %, respectively. The average inter-assay CV percents for T and C were 8.1 % and 6.26 %, respectively.

Attitudes Towards Opponents

Consenting participants completed the ATO questionnaire approximately 20 min after the end of each competition, immediately before giving their 30-min-after-competition sample. The questionnaire consisted of 11 items (Table 1) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree”, 5 = “Strongly Agree”) designed to measure an athlete’s willingness to reconcile with her recent opponent. Items phrased in the negative (items 4 and 9) were reverse scored before analysis. The internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha) for the total scale was 0.87. In general, participants responded systematically higher to 3 items, 3, 6, and 9 (M = 3.6, SD = 0.01) that appear to relate more to the desire to be perceived as a good sport, than the rest of the items (M = 2.33, SD = 0.21). However, removal of these three items reduced internal consistency to 0.82. For the purpose of analysis, participants’ total mean scores on the ATO were used. As there are no pre-existing measures of after-competition attitudes towards reconciliation, these items were developed through qualitative interviews with athletes and selected based on face-validity. Distribution of this measure to a larger sample of 39 women after participating in intramural sporting events resulted in an overall mean score of 4.22/5 (SE = 0.08), significantly higher (i.e., more willing to reconcile) than athletes competing against rival opponents in the present study.

Competitions

The first of the two matches was played at the participants’ home field against Washington University and the second game was played away from home against the University of Chicago. The home match was a narrow 0–1 loss with the one goal scored by the opponents in the 15th minute of the first half. The away match was a narrow 2–0 victory, with the first of two goals scored in the 51st minute of play and the second goal, to secure the win, scored in the final minute of play (89th minute). Both opponents were intra-conference rivals and ranked, along with Emory, in the top 25 NCAA (Division III) teams nationally. Playing at home versus away from home did not appear to influence T and C responses to competition in these athletes (Casto and Edwards 2015).

Statistical Analyses, Hormone Measures, and Transformations

The SPSS statistical package was used for calculation of a repeated-measures t-test (two-tailed) for the difference in ATO score for the game that was lost compared to the game that was won. Correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to test the relationship between ATO score and absolute levels of T and C as well as the percent change in T and C associated with the period of competition and the 30 min period after competition. Relative (percent change) instead of absolute change was used as the primary metric of change because the levels of T and C before and after-competition are influenced by psychologically relevant preceding events (warm-up and competition, respectively, Casto and Edwards 2015). However, some studies use absolute difference to measure hormone change (e.g. Mehta and Josephs 2006). In keeping with this, data for absolute change are included.

Across all participants, baseline T, but not C, levels were normally distributed. For participants included in analyses involving competition and after-competition T and C levels (those who played in each match), data for the change in C after competition for the first match and change in T after competition for the second match were positively skewed. Natural log-transformations were used to normalize the distributions for these hormone measures. In all cases, analysis of transformed data produced the same overall results as analysis of the raw data. Due to the number of correlations conducted, where appropriate, significance was determined after controlling for false discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995).

Results

T and C Change Associated with Competition and the 30 minutes After Competition

Means and standard deviations for T and C associated with each match are shown in Table 2. As reported elsewhere (Casto and Edwards 2015), T and C levels in these athletes significantly increased over the course of warm-up and competition in both games (Table 3). Within the 30 minutes after competition, T levels decreased following both matches, but the decrease was significantly larger following the match that was won compared to the match that was lost (Table 3). However, because the game that was lost was played at home and the game that was won was played away from home, effects due to winning and losing may be confounded with any competition or after-competition effects of venue. C levels remained relatively high for at least 30 minutes after both matches, but decreased more after the match that was won compared to match that was lost (Table 3). T and C changes associated with the competition and after-competition periods were not different for OC users compared to non-users.

ATO Responses

One participant gave incomplete responses to the ATO after the first game. Data for this individual were removed from the Game 1 analyses leaving a total N = 16. For the second game, one participant’s change in T within the 30 minutes after competition exceeded 3 SD of the mean. Data for this individual were removed from the Game 2 analysis leaving a total N = 14, but results for both Winsorization and removal of this outlier are included for reference. There were thirteen women who played in and gave complete ATO responses for both matches.

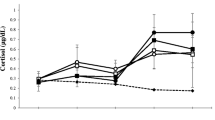

For the thirteen athletes who played in both games, mean ATO score was significantly lower after the game that was lost (M = 2.36, SE = 0.19) than the game that was won (M = 3.35, SE = 0.19), t (12) = −5.31, p < 0.001, d = 1.99. ATO score was not related to T change during competition or C change during or after competition in either match. Additionally, ATO score was not related to absolute levels of T or C at any point. As shown in Fig. 1, in both matches, the percent change in T after competition was significantly and positively correlated with mean score on the ATO (Game 1, loss: r (16) = 0.64, p = 0.007; Game 2 win: r (14) = 0.70, p = 0.005). That is, the higher an athlete’s T remained after competition, the more willing she was to reconcile with her opponent. For the participant whose post-competition T change exceeded 3 SDs from the mean for the second match, Winsorization produced similar results (Game 2 win: r (15) = 0.52, p = 0.046). Using absolute change, instead of percent change, the positive relationship between T and ATO score remains, but is no longer significant for the second of the two games (Game 1, loss: r (16) = 0.51, p = 0.044; Game 2 win: r (14) = 0.37, p = 0.188).

Due to the small sample size for each competition, there is insufficient statistical power to test the potential moderating effect of C on the relationship between T and reconciliation. For the game that was won, only four individuals showed increases in C within the 30 minutes after competition whereas seven individuals increased in C within the 30 minutes after competition following a loss (Fig. 1). The relationship between after-competition T change and mean ATO score does not appear different for these individuals compared to those who decreased in C after competition (Fig. 1).

Discussion

As described in a companion study (Casto and Edwards 2015), for the women soccer players included in this research, intercollegiate competition was associated with a substantial increase in salivary levels of T and C. For T, this increase began with warm-up and continued through to the end of competition. C levels were stable during warm-up, but increased dramatically during competition. Increases in T were seen for both matches and in every one of the women participating in this study, with increases ranging from 10 to 130 % relative to before-warm-up baseline. Similarly, increases in C were seen in a vast majority of the athletes, with levels typically doubling over the course of competition. These findings are consistent with more than a decade of research on hormonal responses to athletic competition in highly-trained women across a wide array of sports (e.g., Bateup et al. 2002; Casto et al. 2014; Edwards et al. 2006; Edwards and Kurlander 2010; Gonzalez-Bono et al. 1999; Hamilton et al. 2009; Suay et al. 1999). The implications and potential function of short-term increases in T and C during competition are discussed elsewhere (Casto et al. 2014; Casto and Edwards 2015).

Win or lose, T typically decreased after the end of competition, reduced by as much as forty percent from peak levels seen 30 minutes earlier. After-competition changes in C were less predictable, and differences between T and C in this regard are discussed elsewhere (Casto and Edwards 2015). But, whether for T or C, the magnitude and direction of the after-competition change in hormone level was highly variable from athlete to athlete – in some individuals, competition-related peak levels of T and/or C were sustained for at least 30 min after the end of competition, in others, hormone levels decreased more quickly. Importantly, after-competition variability in the extent to which T (but not C) was sustained was significantly correlated with an athletes’ willingness to reconcile with an opponent as measured by mean response to the ATO questionnaire. More specifically, the closer an athlete’s 30-min post competition level of T was to her end-of-competition peak, the more willing she was to reconcile with her opponent, and this was true in both victory and defeat.

Although the relationship between T and willingness to reconcile was apparent following both victory and defeat, ATO scores were, on average, significantly lower following defeat than following victory. The dampened desire to engage socially with one’s opponent after a defeat may be due to reduced mood following a sports competition loss (e.g., Gonzalez-Bono et al. 1999). Indeed, mood has a demonstrated influence over various socially-oriented cognitions and behaviors (e.g., Forgas 1984; Isen 1987). Although the emotional reactions to winning and losing are quite different, the relationship between T and individual differences in willingness to reconcile holds for both outcomes.

It is important to note that the relationship between T and reconciliation is one that has to do with hormone kinetics rather than absolute levels of hormones. Absolute levels of T per se were not associated with ATO score for any of the time points sampled. Rather, a woman with an after-competition T level that remained higher relative to her own end-of-competition peak (no matter whether either of those levels were high or low relative to other players) was, typically, more willing to reconcile than a woman whose T level declined more quickly from its end-of-competition peak. Timing is also important. T levels in women’s athletic competition are constantly changing, increasing during warm-up and competition and then decreasing after the end of competition (Casto and Edwards 2015; Casto et al. 2014; Edwards and Kurlander 2010). But, the only period for which change in T level predicted willingness to reconcile was the interval within the 30 minutes after the end of competition – a time when actions towards reconciliation would be most appropriate. Our findings, apparently the first to show a relationship between T and prosocial attitudes towards reconciliation after competition, are in accordance with previous research demonstrating that T administration results in increases in prosocial behavior in women studied in other, more “experimental” contexts (Eisenegger et al. 2010; Boksem et al. 2013; van Honk et al. 2012, but see Zak et al. 2009).

Reconciliation serves a number of functions – to prevent group instability, reduce future aggression, decrease anxiety, and meet the basic psychological need of removing moral/ethical inferiority (for review, Aureli et al. 2002; de Waal 2000; Dovido et al. 2010). Reconciliation may also function as a prosocial means of achieving and/or maintaining social status. Indeed, other prosocial means of achieving status are well documented (Anderson and Kilduff 2009; Cheng et al. 2012; Hawley 1999) and the particular strategy, antisocial or prosocial, likely depends on the social context (e.g., organized sport, a prison cell block, corporate boardroom, high school lunchroom). Athletic competition is a context where sportsmanship and other cultural norms govern expectations for social niceties, particularly after the competition has ended. Consequently, status may be benefited more through acts of social cohesion rather than direct aggression or antisocial behavior following a formal sports contest. And as a result, the relationship between T and the desire to reconcile with an opponent after competition is consonant with the notion that T relates to behavior intended to achieve or maintain social status and individual power-motivation (e.g., Stanton and Schultheiss 2009; Mehta and Josephs 2010; Edwards and Casto 2013; for review, Hamilton et al. 2015). Thus, in influencing or being influenced by social status, relatively higher levels of T may produce a wide range of behaviors so long as they are reinforced with access to power or influence.

In addition to social context, gender/sex could also play a role in determining whether relatively higher levels of T relate to prosocial or antisocial behavior, but current evidence is inconclusive. Although, both men and women use prosocial strategies to attain status (Anderson and Kilduff 2009; Cheng et al. 2012; Hawley 1999), studies that demonstrate a positive relationship between T and antisocial behavior have been mostly conducted with men (e.g. Dabbs and Morris 1990; for review, Archer 2006) and studies that demonstrate a positive relationship between T and prosocial behavior have been mostly conducted with women (e.g., Boskem et al. 2013; Eisenegger et al. 2010; van Honk et al. 2012) – a bias that may inappropriately lead researchers to predict a sex difference. The present study was conducted with women. Whether the same prosocial relationship between changing levels of after-competition T and reconciliation holds true for men remains to be determined.

Some reports are seemingly inconsistent with the finding that T relates to prosocial behaviors like reconciliation. For example, basal T appears inversely related to the ability to accurately infer the thoughts and feelings of others (Ronay and Carney 2013), colleagues’ ratings of one’s leadership abilities (Ronay and Carney 2013), and performance in cooperative competition (Mehta et al. 2009). In women, administration of T appears to reduce behaviors thought to reflect empathy (Hermans et al. 2006; van Honk and Schutter 2007; van Honk et al. 2011) and, in one study, increased egocentric decision-making (Wright et al. 2012). However, the desire to reconcile with an opponent and attempts to do so are probably not motivated by inherently altruistic motives (Eisenegger et al. 2010) or necessarily benefitted by the ability to infer minute emotional dispositions. Reconciliation can be self-serving (e.g., a strategy for promoting one’s status) and, at the same time, beneficial to others (i.e., prosocial), but none of these effects seem obviously served by empathy. Additionally, when considering studies that may or may not agree on hormone-behavior relationships, it is also important to distinguish between the effects or correlates of basal/baseline levels of hormones and the effects or correlates of dynamic/rapidly changing levels of hormones (Carré and Olmstead 2015, p.172). The long and short-term influence of hormones on behavior and physiology are distinct and in some instances even opposing (e.g. Crewther et al. 2011; Stanton and Schultheiss 2007; Edwards and Casto 2013). Additionally, differences in the effects of endogenous hormone levels (basal or rapidly fluctuating) compared to exogenously administered supraphysiological doses are not well-understood. Studies exploring the relationship between T and social behavior would only be truly contradictory if presenting opposing effects that were at least matched on whether or not the hormone levels reflect an endogenous or exogenous source and whether or not the endocrine metric reflected basal or dynamic levels.

Interpretation of the results from the present study is limited by the small sample size. Despite the small number of participants, this study was conducted in a naturalistic competition setting and across two separate matches. Importantly, the principal effect for this study is demonstrated on two separate occasions, a victory and a defeat. But, it is imperative that future research explore the relationship between T and reconciliation and the interaction between T and C in predicting reconciliation behavior with a larger sample size in both real-world settings and in competitive laboratory contexts.

Conclusion

For a competing woman athlete, T typically increases over the course of competition. The degree to which after-competition T levels are sustained reflects her willingness to reconcile with a recent opponent in victory and defeat. Sustained high levels of T may motivate reconciliation and other prosocial behavior at times when status is benefitted more through social cohesion rather than overt aggression. In review of the history of research on conflict resolution among non-human primates, de Waal (2000) describes how decades of research centered around an individual model of aggression led to an impoverished understanding of behavior, its antecedents, and consequences. Instead, de Waal argues that a more comprehensive understanding requires a model of the individual that is socially integrated as, for example, “high-ranking individuals are not necessarily the strongest, but the ones that can mobilize the most support” (de Waal 2000, p. 586). In keeping with this, the demonstration of a positive relationship between T and reconciliation in the present study should encourage studies of the link between T and status striving that extend beyond the aggressively power-motivated individual to the socially embedded context in which that individual achieves and maintains his or her status.

References

Anderson, C., & Kilduff, G. J. (2009). The pursuit of status in social groups. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 295–298.

Archer, J. (2006). Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30, 319–345.

Aureli, F., & van Schaik, C. P. (1991). Post-conflict behaviour in long-tailed macaques (macaca fascicularis): II coping with the uncertainty. Ethology, 89, 101–114.

Aureli, F., Cords, M., & van Schaik, C. P. (2002). Conflict resolution following aggression in gregarious animals: a predictive framework. Animal Behaviour, 64, 325–343.

Bateup, H. S., Booth, A., Shirtcliff, E. A., & Granger, D. A. (2002). Testosterone, cortisol, and women’s competition. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 181–192.

Bedgood, D., Boggiano, M. M., & Turan, B. (2014). Testosterone and social evaluative stress: the moderating role of basal cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 47, 107–115.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B, 57, 289–300.

Boksem, M. A. S., Mehta, P. H., Van der Bergh, B., van Son, V., Trautmann, S. T., et al. (2013). Testosterone inhibits trust but promotes reciprocity. Psychological Science, 24, 2306–2314.

Book, A. S., Starzyk, K. B., & Quinsey, V. L. (2001). The relationship between testosterone and aggression: a meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6, 579–599.

Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (1997). Human aggression in evolutionary psychological perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 605–619.

Carré, J. M., & Olmstead, N. A. (2015). Social neuroendocrinology of human aggression: examining the role of competition-induced testosterone dynamics. Neuroscience, 286, 171–186.

Casto, K. V., & Edwards, D. A. (2015). Before, during, and after: how phases of competition differentially affect testosterone, cortisol, and estradiol levels in women athletes. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology. doi:10.1007/s40750-015-0028-2.

Casto, K. V., Elliott, C. M., & Edwards, D. A. (2014). Intercollegiate cross country competition: effects of warm-up and racing on salivary levels of cortisol and testosterone. International Journal of Exercise Science, 7, 318–328.

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 103–125.

Coie, J., Dodge, K., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: a cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570.

Crewther, B. T., Cook, C., Cardinale, M., Weatherby, R. P., & Lowe, T. (2011). Two emerging concepts for elite athletes: the short-term effects of testosterone and cortisol on the neuromuscular system and the dose-response training role of these endogenous hormones. Sports Medicine, 41, 103–123.

Dabbs, J. M. (1991). Salivary testosterone measurements: collecting, storing, and mailing saliva sample. Physiology & Behavior, 49, 815–817.

Dabbs, J. M., & Morris, R. (1990). Testosterone, social class, and antisocial behavior in a sample of 4,462 men. Psychological Science, 1, 209–211.

de Waal, F. B. M. (1984). Coping with social tension: sex differences in the effect of food provision to small rhesus monkey groups. Animal Behaviour, 32, 765–773.

de Waal, F. B. M. (1986). The integration of dominance and social bonding in primates. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 61, 459–479.

de Waal, F. B. M. (2000). Primates: a natural heritage of conflict resolution. Science, 289, 586–590.

Dovidio, J. F., Johnson, J. D., Gaertner, S. L., Pearson, A. R., Saguy, T., & Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2010). Empathy and intergroup relations. In M. Mikulincer, & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior (pp. 393–429). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Edwards, D. A., & Casto, K. V. (2013). Women’s intercollegiate athletic competition: cortisol, testosterone, and the dual-hormone hypothesis as it relates to status among teammates. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 153–160.

Edwards, D. A., & Casto, K. V. (2015). Baseline cortisol moderates testosterone reactivity to women’s intercollegiate athletic competition. Physiology & Behavior, 142, 48–51.

Edwards, D. A., & Kurlander, L. S. (2010). Women’s intercollegiate volleyball and tennis: effects of warm-up, competition, and practice on saliva levels of cortisol and testosterone. Hormones and Behavior, 58, 606–613.

Edwards, D. A., Wetzel, K., & Wyner, D. R. (2006). Intercollegiate soccer: saliva cortisol and testosterone are elevated during competition, and testosterone is related to status and social connectedness with teammates. Physiology & Behavior, 87, 135–143.

Eisenegger, C., Naef, M., Snozzi, R., Heinrichs, M., & Fehr, E. (2010). Prejudice and truth about the effect of testosterone on human bargaining behavior. Nature, 463, 356–361.

Eisenegger, C., Haushofer, J., & Fehr, E. (2011). The role of testosterone in social interaction. Trends in Cognitive Neuroscience, 15, 263–271.

Elias, M. (1981). Serum cortisol, testosterone, and testosterone-binding globulin responses to competitive fighting in human males. Aggressive Behavior, 7, 215–224.

Filaire, E., Alix, D., Ferrand, C., & Verger, M. (2009). Psychophysiological stress in tennis players during the first single match of a tournament. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34, 150–157.

Forgas, J. P. (1984). The influence of mood on perceptions of social interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 20, 497–513.

Gonzalez-Bono, E., Salvador, A., Serrano, M. A., & Ricarte, J. (1999). Testosterone, cortisol, and mood in a sports team competition. Hormones and Behavior, 35, 55–62.

Granger, D. A., Shirtcliff, E. A., Booth, A., Kivlighan, K. T., & Schwartz, E. B. (2004). The “trouble” with salivary testosterone. Psychoneurocrinology, 29, 1229–1240.

Hamilton, L. D., van Anders, S. M., Cox, D. N., & Watson, N. V. (2009). The effect of competition on salivary testosterone in elite female athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 4, 538–542.

Hamilton, L. D., Carré, J. M., Mehta, P. H., Olmstead, N., & Whitaker, J. D. (2015). Social neuroendocrinology of status: a review and future directions. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 1, 202–230.

Hawley, P. H. (1999). The ontogenesis of social dominance: a strategy-based evolutionary perspective. Developmental Review, 19, 97–132.

Hermans, E. J., Putman, P., & Van Honk, J. (2006). Testosterone administration reduces empathetic behavior: a facial mimicry study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 31, 859–866.

Hogg, M. A. (2005). Social identity and leadership. In D. M. Messick, & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), The psychology of leadership: new perspectives and research (pp. 53–80). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. In G. Meurant (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 20, pp. 203–247). San Diego: Academic Press.

Jiménez, M., Aguilar, R., & Alvero-Cruz, J. R. (2012). Effects of victory and defeat on testosterone and cortisol response to competition: evidence for same response patterns in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37, 1577–1581.

Mazur, A., & Booth, A. (1998). Testosterone and dominance in men. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 21, 353–363.

McCullough, M. E., Pedersen, E. J., Tabak, B. A., & Carter, E. C. (2014). Conciliatory gestures promote forgiveness and reduce anger in humans. Pnas, 111, 11211–11216.

Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2006). Testosterone change after losing predicts the decision to compete again. Hormones and Behavior, 50, 684–692.

Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2010). Testosterone and cortisol jointly regulate dominance: evidence for a dual-hormone hypothesis. Hormones and Behavior, 58, 898–906.

Mehta, P. H., Wuehrmann, E. V., & Josephs, R. A. (2009). When are low testosterone levels advantageous? The moderating role of individual versus intergroup competition. Hormones and Behavior, 56, 158–162.

Popper, M. (2005). Leaders who transform society: what drives them and why we are attracted. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Ronay, R., & Carney, D. R. (2013). Testosterone’s negative relationship with empathic accuracy and perceived leadership ability. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4, 92–99.

Silk, J. B. (2002). The form and function of reconciliation in primates. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31, 21–44.

Stanton, S. J., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2007). Basal and dynamic relationships between implicit power motivation and estradiol in women. Hormones and Behavior, 52, 571–580.

Stanton, S. J., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2009). The hormonal correlates of implicit power motivation. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 942–949.

Suay, F., Salvador, A., González-Bono, E., Sanchís, C., Martínez, M., Martínez-Sanchis, S., Simón, V. M., & Montoro, J. B. (1999). Effects of competition and its outcome on serum testosterone, cortisol and prolactin. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 24, 551–566.

Vaillancourt, T., & Hymel, S. (2006). Aggression and social status: the moderating roles of sex and peer-valued characteristics. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 396–408.

van Anders, S. M. (2010). Chewing gum has large effects on salivary testosterone, estradiol, and secretory immunoglobulin a assays in women and men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35, 305–309.

van Honk, J., & Schutter, D. J. L. G. (2007). Testosterone reduces conscious detection of signals serving social correction implications for antisocial behavior. Psychological Science, 18, 663–667.

van Honk, J., Schutter, D. J., Bos, P. A., Kruijt, A.-W., Lentjes, E. G., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2011). Testosterone administration impairs cognitive empathy in women depending on second-to-fourth digit ratio. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 3448–3452.

van Honk, J., Montoya, E. R., Bos, P. A., van Vugt, M., & Terburg, D. (2012). New evidence on testosterone and cooperation. Nature, 485, E4–E5.

Wibral, M., Dohmen, T., Klingmüller, D., Weber, B., & Falk, A. (2012). Testosterone administration reduces lying in men. PloS One. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046774.

Wirth, M. M., Welsh, K. M., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2006). Salivary cortisol changes in humans after winning or losing a dominance contest depend on implicit power motivation. Hormones and Behavior, 49, 346–352.

Wright, N. D., Bahrami, B., Johnson, E., Di Malta, G., Rees, G., Frith, C. D., & Dolan, R. J. (2012). Testosterone disrupts human collaboration by increasing egocentric choices. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, rspb20112523.

Zak, P. J., Kurzban, R., Ahmadi, S., Swerdloff, R. S., Park, J., et al. (2009). Testosterone administration decreases generosity in the ultimatum game. PloS One, 4, e8330.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Emory University varsity women’s soccer coach, Sue Patberg, assistant coach Rachel Moreland, and the 2013 varsity women’s team for their participation in the research described in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study complies with the laws for research with human subjects in the United States and was approved by Emory University’s IRB. All persons gave written informed consent prior to participation in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Casto, K.V., Edwards, D.A. Testosterone and Reconciliation Among Women: After-Competition Testosterone Predicts Prosocial Attitudes Towards Opponents. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 2, 220–233 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-015-0037-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-015-0037-1