Abstract

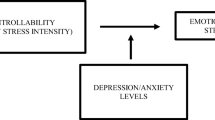

Recent research on vulnerabilities to depression and anxiety has begun to de-emphasize cognitive content in favor of the responsiveness of the individual to variations in situational context in arriving at explanations of events (explanatory flexibility) or attempts to cope with negative events (coping flexibility). The present study integrates these promising avenues of conceptualization by assessing the respective contributions of explanatory and coping flexibility to current levels of depression and anxiety symptoms. Results of structural equation modeling support a model of partial mediation in which both explanatory flexibility and coping flexibility independently contribute to the prediction of latent negative affect, with coping flexibility partially mediating the influence of explanatory flexibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cohen’s (1988) effect size f is used in ANOVA analyses and has small, medium, and large conventions of .10, .25, and .40 respectively.

Stone et al. (1991) and others highlight a number of limitations of extant self-report coping measures, particularly those based on the transactional model of coping. In a recent critique of self-report coping measures, Coyne and Racioppo (2000) argued that more situation-specific inventories would produce more meaningful results than traditional self-reported coping measures. The CSFI was designed to circumvent the limitations of coping measures that do not specify a time period for coping or the type of situations on which respondents are reporting and that have respondents rate their use of coping strategies in response to a single stressful situation. Finally, the CSFI was designed to provide a functional assessment of coping aims (i.e., the underlying purpose of coping) to circumvent difficulties associated with attempting to discern the function of coping based on the specific strategies or tactics that individuals endorse on self-report inventories.

The unselected college student sample had overall low levels of distress. On the BAI, 55% of the sample scored in the minimal range (0–7); 38% scored in the mild range (8–15); and 7% scored in the moderate range. On the BDI-II, as a total score, 84% scored in the minimal range (0–13); 12% scored in the mild range (14–19); and 4% scored in the moderate range. The restricted range of the manifest anxiety and depression symptom variables, and the subsequent latent negative affectivity variable, may have attenuated the relations between coping flexibility, explanatory flexibility, and negative affectivity in this sample.

Path analysis models with either BDI-II or BAI as dependent manifest variables, as well as a structural model in which the latent negative affect variable was assessed only with the BDI-II and BAI indicators, were also examined and produced comparable results. These results are available upon request of the corresponding author.

The Sobel test provides a test of the extent to which the mediator significantly carries the influence of an independent variable to a dependent variable (i.e., the indirect path). A significant Sobel z indicates that the mediator does significantly carry the influence from the IV to the DV. Freedman and Schatzkin (1992) provide a test of the difference between the adjusted and unadjusted regression coefficient (i.e., the change in the direct path with the inclusion of the mediator in the model). MacKinnon et al. (2002) provide evidence from a Monte Carlo study that compared 14 methods to testing mediation that the Sobel (1982) and Freedman and Schatzkin (1992) tests have the most power and the most accurate Type I error rates for statistically testing mediation in most situations.

References

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74.

Amirkhan, J. H. (1990). A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The coping strategy indicatory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1066–1074.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Beck, A. T., & Clark, D. A. (1997). An information processing model of anxiety: Automatic and strategic processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 49–58.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 56, 893–897.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: 25 years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100.

Brosschot, J. F. & Thayer, J. F. (2004). Worry, Perseverative Thinking and Health. In Nyklicek, I., Temoshok, L., Vingerhoets, A. (Eds.). Emotinal expression and health: Advances in theory, assessment, and clinical application (pp. 99–114). Hove, East Sussex, England: Brunner-Routledge.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283.

Coyne, J. C., & Racciopo, M. (2000). Never the twain shall meet? Closing the gap between coping research and clinical intervention research. American Psychologist, 55, 655–664.

Freedman, L. S., & Schatzkin, A. (1992). Sample size for studying intermediate endpoints within intervention trials of observational studies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 136, 1148–1159.

Fresco, D. M., Rytwinski, N. K., & Craighead, L. W. (in press). Explanatory flexibility and negative life events interact to predict depression symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology.

Fresco, D. M., Heimberg, R. G., Abramowitz, A., & Bertram, T. L. (2006a). The effect of a negative mood priming challenge on dysfunctional attitudes, explanatory style, and explanatory flexibility. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 167–183.

Fresco, D. M., Schumm, J. A. & Dobson, K. S. (2006b). Explanatory flexibility and explanatory style: Modality-specific mechanisms of change when comparing behavioral activation with and without cognitive interventions. Submitted for publication.

Gotlib, I. H., McLachlan, A. L., & Katz, A. N. (1988). Biases in visual attention in depressed and nondepressed individuals. Cognition and Emotion, 2, 185–200.

Isen, A. M., & Daubman, K. A. (1984). The influence of affect on categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1206–1217.

Johnsen, B. H., Thayer, J. F., Laberg, J. C., Wormnes, B., Raadal, M., Skaret, E., Kvale, G., Berg, E. (2003). Attentional and physiological characteristics of patients with dental anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17, 75–87.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

McCabe, S. B., Gotlib, I. H., & Martin, R. A. (2000). The deployment-of-attention task and vulnerability to depression: Sad mood induction and history of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 427–444.

McCabe, S. B., & Toman, P. E. (2000). Stimulus exposure duration in a deployment-of-attention task: Effects on dysphoric, recentlydysphoric, and nondysphoric individuals. Cognition and Emotion, 14, 125–142.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104.

Miller, S. M., Shoda, Y., & Hurley, K. (1996) Applying cognitive-social theory to health-protective behavior: Breast self-examination in cancer screening. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 70–94.

Peterson, C., Semmel, A., von Baeyer, C., Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1982). The attributional style questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6, 287–300.

Rosenbaum, M., & Ben-Ari, K. (1985). Learned helplessness and learned resourcefulness. Effects of noncontingent success and failure on individuals differing in self-control skills. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 198–215.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In Leinhardt, S. (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1982 (pp. 290–312). Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Stone, A. A., Greenberg, M. A., Kennedy-Moore, E., & Newman, M. G. (1991). Self-report, situation-specific coping questionnaires: What are they measuring? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 648–658.

Thayer, J. F. & Lane, R. D. (2002). Perseverative thinking and health: Neurovisceral concomitants. Psychology and Health, 17, 685–695.

Williams, N. L. (2002). The cognitive interactional model of appraisal and coping: Implications for anxiety and depression. Fairfax, VA: Dissertation. George Mason University.

Williams, N. L. (2006). Coping styles and coping flexibility as vulnerabilities to emotional disorders. Submitted for publication.

Wilson, K. G., & Murrell, A. R. (2004). Values work in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Setting a course for behavioral treatment. In S. C., Hayes, V. M., Follette, & M., Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the cognitive behavioral tradition (pp. 120–151). New York: Guilford Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fresco, D.M., Williams, N.L. & Nugent, N.R. Flexibility and Negative Affect: Examining the Associations of Explanatory Flexibility and Coping Flexibility to Each Other and to Depression and Anxiety. Cogn Ther Res 30, 201–210 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9019-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9019-8