Brain: Decoding the infrastructure of the cerebellum

Our brains must constantly juggle and combine a multitude of daily tasks, such as talking while walking, or planning our next move. These seemingly mundane actions rely on complex brain networks that interact through anatomical hubs formed of several types of cells. For example, a brain structure called the cerebellum is connected to various networks in the lower and higher brainstem, which it uses to help coordinate conscious and unconscious movements as well as cognitive processes like decision-making (Gao et al., 2018; Chabrol et al., 2019). The cerebellum is divided into a series of compartments known as cerebellar nuclei, which are split into multiple groups of cells (Teune et al., 2000). Some of these cell groups have overlapping or related roles, making it difficult to determine which structures in the cerebellum are linked to specific tasks (Romano et al., 2020).

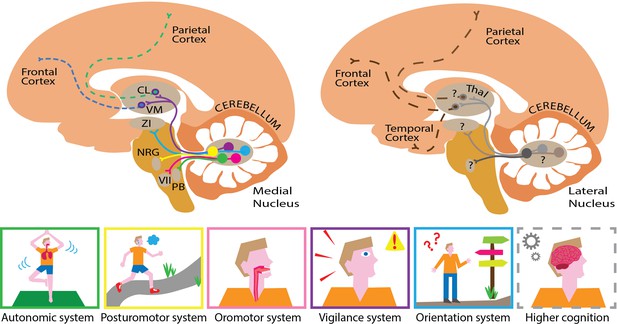

For instance, the medial and lateral cerebellar output nuclei, which share many anatomical targets, show both similarity and differences in their connections (or ‘projections’) to these sites (Middleton and Strick, 1997; Teune et al., 2000). Indeed, recent physiological studies suggest that these medial and lateral compartments, respectively, play a role in simple and complex forms of motor planning (Gao et al., 2018; Chabrol et al., 2019). However, both studies used manipulations that were not cell-specific, making it difficult to establish detailed conclusions on the origin of control. This illustrates why it is important to disentangle how individual groups of cells within the two nuclei connect to downstream brain networks involved in planning actions. Now, in eLife, Hirofumi Fujita, Sascha du Lac and Takashi Kodama from Johns Hopkins University report a new cell-specific approach, presenting the most comprehensive, functional connectivity study of any cerebellar nucleus to date (Fujita et al., 2020).

The team used single-cell gene expression analysis and immunohistochemistry to explore the different groups of cells present in the medial cerebellar nucleus of mice. This revealed five distinct subgroups of cells: four groups differed based on molecular expression patterns, including one which could be split into two further subgroups based on anatomical location.

Next, Fujita et al. carried out a series of tracer experiments to map how each of the five identified subgroups was connected to different areas of the brain. This approach used viral transneuronal tracers, which exploit the ability for certain viruses to ‘jump’ across the junction that connects two neurons. The resulting input-output maps were nearly completely segregated. This highlighted that each subgroup in the nucleus had divergent projection patterns and was anatomically connected to separate, large-scale networks that play different roles in voluntary or involuntary ‘autonomic’ functions (Figure 1). The constitution of these networks suggest that some may be predisposed to transmit fast signals, while others transmit signals more slowly. This is a crucial step for understanding how different cell groups in the medial nucleus may play specific roles, and how they may work together to integrate different types of responses (Romano et al., 2020).

Mapping the substructures and projections of the medial and lateral cerebellar nuclei.

Five different cell groups can be identified in the medial cerebellar nucleus (left). Each projects to a specific downstream network of targets, which serve a set of related functions (bottom panel). For example, cells that project to the zona incerta (ZI; blue pathway) help control orientation, while cells that project to the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (NRG; yellow pathway) are involved in regulating posture. The projections highlighted here form only a small part of the actual elaborate networks shown by Fujita and colleagues. This approach could also be used to elucidate pathway-specific cell groups in the lateral cerebellar nucleus (right). This compartment presumably projects to similar parts of the cerebral cortex (dashed lines) through different hubs that probably serve higher cognitive functions. This illustrates how the medial and lateral cerebellum might complement each other, targeting similar, but distinct hubs that relay signals to partially overlapping areas in the brain. The cortex is shown in light orange, the cerebellum in dark orange, the brainstem in mustard and the thalamus (Thal) in light brown. CL refers to the centrolateral nucleus of the thalamus, PB to the parabrachial nucleus, VM to the ventromedial nucleus of the thalamus, and VII to the facial motor nucleus.

Image credit: Chris I. De Zeeuw, Willem S. van Hoogstraten and Valentina Riguccini (CC BY 4.0).

There are, however, potential caveats associated with the individual high-end technical methods harnessed in this study. For example, the approaches used to genetically engineer the labels used in the viral transneuronal tracing experiments may allow some neurons to be tagged by accident, and for brain cells to be misidentified as being part of the output network the nucleus connects to (Sjulson et al., 2016; Song and Palmiter, 2018; Zingg et al., 2017). It was therefore reassuring that Fujita et al. used multiple approaches to confirm their major high-tech observations, and that they only reported projections previously identified by conventional tracing. These decisions reduced the likelihood of false-positive interpretations – that is, incorrectly reporting neurons as belonging to the network.

Similarly, further experiments could also be conducted to avoid potential false-negative labelling – failing to report neurons which connect to subgroups in the medial cerebellar nucleus. In particular, it could be worthwhile to dedicate another line of transneuronal tracing experiments to the hubs in the rest of the brain that the medial cerebellar cell groups connect to. These downstream nuclei display widespread connectivity to other parts of the brain, suggesting that specific cell groups in the medial cerebellar nucleus connect to other networks through particular second-order neurons in these hubs (Wang et al., 2020).

Identifying genetically distinct groups of neurons, combined with elucidating their specific projection networks, may well pave the way for new breakthroughs. For instance, this could be used as a roadmap to alter the function of specific cell groups in the medial nucleus as animals perform tasks of interest. Moreover, the same genetically-driven approach deployed by Fujita et al. could help to identify different subgroups within the lateral cerebellar nucleus, allowing direct functional comparisons with the medial nucleus (Figure 1). This would help to understand the extent to which specific cell groups in the medial and lateral cerebellum overlap or complement one another in controlling autonomic, sensorimotor or cognitive functions (Gao et al., 2018; Chabrol et al., 2019; Romano et al., 2020).

In addition to showing how to alter specific cell types in the medial nucleus at a high spatial resolution, Fujita et al. reveal how to manipulate these cells over time. Their work highlights the proteins required for signals to be transduced quickly or slowly, and it connects the nuclei neurons that express these proteins to fast or slow inhibitory cell inputs. Ultimately, this provides all the knowledge needed to design meaningful functional experiments, offering a bewildering palette of insight that should inspire neuroscientists for many years to come.

References

-

Dentate output channels: motor and cognitive componentsProgress in Brain Research 114:553–566.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63386-5

-

Cell-specific targeting of genetically encoded tools for neuroscienceAnnual Review of Genetics 50:571–594.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035011

-

Detecting and avoiding problems when using the Cre-lox systemTrends in Genetics 34:333–340.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2017.12.008

-

Topography of cerebellar nuclear projections to the brain stem in the ratProgress in Brain Research 124:141–172.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(00)24014-4

-

Zona incerta: an integrative node for global behavioral modulationTrends in Neurosciences 43:82–87.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2019.11.007

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: August 19, 2020 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2020, van Hoogstraten and De Zeeuw

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,545

- views

-

- 287

- downloads

-

- 1

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Primates can recognize objects despite 3D geometric variations such as in-depth rotations. The computational mechanisms that give rise to such invariances are yet to be fully understood. A curious case of partial invariance occurs in the macaque face-patch AL and in fully connected layers of deep convolutional networks in which neurons respond similarly to mirror-symmetric views (e.g. left and right profiles). Why does this tuning develop? Here, we propose a simple learning-driven explanation for mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning. We show that mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning for faces emerges in the fully connected layers of convolutional deep neural networks trained on object recognition tasks, even when the training dataset does not include faces. First, using 3D objects rendered from multiple views as test stimuli, we demonstrate that mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning in convolutional neural network models is not unique to faces: it emerges for multiple object categories with bilateral symmetry. Second, we show why this invariance emerges in the models. Learning to discriminate among bilaterally symmetric object categories induces reflection-equivariant intermediate representations. AL-like mirror-symmetric tuning is achieved when such equivariant responses are spatially pooled by downstream units with sufficiently large receptive fields. These results explain how mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning can emerge in neural networks, providing a theory of how they might emerge in the primate brain. Our theory predicts that mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning can emerge as a consequence of exposure to bilaterally symmetric objects beyond the category of faces, and that it can generalize beyond previously experienced object categories.

-

- Neuroscience

The nucleus incertus (NI), a conserved hindbrain structure implicated in the stress response, arousal, and memory, is a major site for production of the neuropeptide relaxin-3. On the basis of goosecoid homeobox 2 (gsc2) expression, we identified a neuronal cluster that lies adjacent to relaxin 3a (rln3a) neurons in the zebrafish analogue of the NI. To delineate the characteristics of the gsc2 and rln3a NI neurons, we used CRISPR/Cas9 targeted integration to drive gene expression specifically in each neuronal group, and found that they differ in their efferent and afferent connectivity, spontaneous activity, and functional properties. gsc2 and rln3a NI neurons have widely divergent projection patterns and innervate distinct subregions of the midbrain interpeduncular nucleus (IPN). Whereas gsc2 neurons are activated more robustly by electric shock, rln3a neurons exhibit spontaneous fluctuations in calcium signaling and regulate locomotor activity. Our findings define heterogeneous neurons in the NI and provide new tools to probe its diverse functions.