-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sidra Goldman-Mellor, Alice M. Gregory, Avshalom Caspi, HonaLee Harrington, Michael Parsons, Richie Poulton, Terrie E. Moffitt, Mental Health Antecedents of Early Midlife Insomnia: Evidence from a Four-Decade Longitudinal Study, Sleep, Volume 37, Issue 11, 1 November 2014, Pages 1767–1775, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4168

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Insomnia is a highly prevalent condition that constitutes a major public health and economic burden. However, little is known about the developmental etiology of adulthood insomnia.

We examined whether indicators of psychological vulnerability across multiple developmental periods (psychiatric diagnoses in young adulthood and adolescence, childhood behavioral problems, and familial psychiatric history) predicted subsequent insomnia in adulthood.

We used data from the ongoing Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a population-representative birth cohort study of 1,037 children in New Zealand who were followed prospectively from birth (1972–1973) through their fourth decade of life with a 95% retention rate.

Insomnia was diagnosed at age 38 according to DSM-IV criteria. Psychiatric diagnoses, behavioral problems, and family psychiatric histories were assessed between ages 5 and 38.

In cross-sectional analyses, insomnia was highly comorbid with multiple psychiatric disorders. After controlling for this concurrent comorbidity, our results showed that individuals who have family histories of depression or anxiety, and who manifest lifelong depression and anxiety beginning in childhood, are at uniquely high risk for age-38 insomnia. Other disorders did not predict adulthood insomnia.

The link between lifelong depression and anxiety symptoms and adulthood insomnia calls for further studies to clarify the neurophysiological systems or behavioral conditioning processes that may underlie this association.

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia is a highly prevalent condition that affects 10% to 20% of adults and constitutes a major public health and economic burden.1–5 The pathogenesis of adult insomnia, however, is incompletely understood. Preexisting mental health problems appear to constitute one important risk indicator. Insomnia and other psychiatric disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, are highly comorbid in cross-sectional samples.3,6,7 The mechanisms underlying this comorbidity are still uncertain and likely to be complex in nature. Many studies show that individuals with insomnia are more likely to develop future psychiatric disorders.8–10 Researchers have also reported, however, that psychopathology—most notably the internalizing disorders of depression and anxiety—may manifest prior to and increase risk for the development of adult insomnia.11–16

This developmental vulnerability to insomnia may involve more psychopathologies and begin earlier than previous studies have been able to examine. Cross-sectional associations have been reported between poor sleep and externalizing disorders, especially alcohol dependence17,18 and delinquent behavior or attention deficit disorder in children or adolescents.19,20 Whether externalizing disorders during development convey long-term risk for adult insomnia is not known. In general, the extent to which insomnia is predicted by early-emerging psychopathological difficulties remains unclear.

In this study, we make use of data from a four-decade-long New Zealand birth cohort to examine the link between multiple mental health problems across the lifecourse—including both internalizing and externalizing disorders—and subsequent insomnia in early midlife. In examining lifecourse mental health problems, we focused on three developmental periods: childhood, when behavioral problems predictive of later psychological disorder first emerge; adolescence, when severe cases of diagnosable disorder become apparent; and young adulthood, when incidence of psychological disorder reaches its peak and psychiatric problems may become entrenched. We also examined study members' familial history of psychological disorders, which can serve as both a proxy for genetic risk and as a useful indicator of clinical prognosis.21–23 We hypothesized that internalizing disorders across development would be the strongest predictors of adult insomnia, but that externalizing disorders would also convey excess insomnia risk. We further hypothesized that any association between internalizing or externalizing disorders and adult insomnia would exhibit a dose-response relationship, with more cumulative lifetime diagnoses predicting higher insomnia risk.

We focus on individuals diagnosed with insomnia at early midlife, in their late 30s. People between 35 and 45 have some of the highest rates of insomnia of any age group.1,24 Furthermore, midlife adults are consolidating their careers and serving as the main economic provider for their families. These responsibilities require substantial energy and productivity, which may be undermined by sleeping problems.1,25 The public health burden of insomnia may therefore be greatest among people in their 30s and 40s.

METHODS

Sample

Participants are members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal investigation of health and behavior in a complete birth cohort.26 Study members (N = 1,037; 91% of eligible births; 52% male) were all individuals born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand, who were eligible for the longitudinal study based on residence in the province at age 3 and who participated in the first follow-up assessment at age 3. The cohort represents the full range of socioeconomic status in the general population of New Zealand's South Island and is primarily white. Assessments were carried out at birth and at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, and, most recently, 38 years, when 95% of the 1,007 study members still alive took part. At each assessment wave, study members are brought to the research unit for a full day of interviews and examinations. The Otago Ethics Committee approved each phase of the study and informed consent was obtained.

Measures

Insomnia Diagnosis

At the age-38 assessment in 2010-2012, study members were asked how often they had problems sleeping in the past month because they could not get to sleep within 30 minutes, woke up in the middle of the night, woke up in the early morning, or felt that their sleep was unrefreshing. Individuals were diagnosed with insomnia if they reported having ≥ 1 of the 4 sleep difficulties ≥ 3 times per week, and also reported that their sleep problems affected their lives ≥ 3 times per week in at least 1 of the following domains: (a) work, (b) ability to concentrate, (c) memory, (d) daytime sleepiness, (e) levels of energy or fatigue, (f) levels of irritability,27 or (g) staying awake while driving, eating, or engaging in social activity.28 This definition meets the primary diagnostic criteria for insomnia according to the then-current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Version 4 (DSM-IV); however, we did not impose the DSM-IV exclusionary criteria (e.g., presence of comorbid conditions).

Mental Health Correlates

We first assessed cross-sectional comorbidity between insomnia and other psychiatric conditions at age 38. We then assessed whether antecedent mental health issues predicted age-38 insomnia, focusing on the 3 key developmental periods: young adulthood (ages 18-32), when study members were completing their education and starting their careers; adolescence (ages 11-15), which corresponds to study members' secondary school years; and childhood (ages 5-11), which corresponds to study members' primary school years. Sleep difficulties are a criterion symptom in some psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression), and a frequent complaint in other disorders (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).3 Moreover, disorders at age 38 may be a continuation of mental health problems from earlier in life.29,30 To rule out these potential confounds, we used age-38 concurrent disorders as a covariate when testing whether antecedent mental health problems predict early midlife insomnia.

Concurrent psychiatric conditions. At age 38, psychiatric diagnoses were made using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule,31,32 following the DSM-IV criteria with a reporting period of 12 months.33 Prevalence estimates and comparisons to U.S. and New Zealand national surveys have been previously reported.34 Disorders examined at 38 years were major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, any fear or phobia (including panic disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, and simple phobia), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol dependence, cannabis dependence, and hard drug dependence. Hard drugs included stimulants (e.g., amphetamines, speed), sedatives (e.g., tranquillizers, barbiturates), opiates (e.g., heroin, codeine, opium), hallucinogens (e.g., LSD, mescaline), inhalants (e.g., flue, toluene), cocaine or crack, or being on methadone maintenance.

Two of these psychiatric disorders, depression and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), include sleep problems among the diagnostic criteria. Analyses examining associations between these two age-38 disorders and insomnia were re-run, using modified diagnostic criteria that excluded the sleep items. Results were substantively identical (estimates varied by < 4%); therefore, the full standard diagnostic measures were used in all analyses.

Persistent psychiatric conditions in young adulthood. In community cohorts, many young adults experience psychiatric episodes that occur only once and are relatively mild, involve little impairment, and are unlikely to prompt clinical attention. In contrast, adult individuals with persistent disorder are considerably less common, and tend to have severe disorder and need clinical intervention.34 For this reason, we focus on the occurrence of persistent disorder during young adulthood. Study members were considered to have a persistent psychiatric condition if they were diagnosed with a disorder at ≥ 2 assessment occasions across at ages 18, 21, 26, and 32 years. At ages 18 and 21, disorders were diagnosed according to DSM-III-R criteria.35 At ages 26 and 32, diagnoses were made following DSM-IV criteria. Disorder persistence analyses included major depression, any anxiety disorder (i.e., generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], panic disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, and simple phobia), alcohol dependence, and cannabis dependence. (Hard drug dependence and PTSD were only assessed starting at age 26, so were not included in persistence analyses.)

Psychiatric conditions in adolescence. Psychiatric diagnoses at 11, 13, and 15 years of age were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children,36 following the then-current DSM-III criteria.37 Study members were defined as having a diagnosis during adolescence if they met criteria for that diagnosis at any of these assessments. We focused on single diagnoses during the adolescent developmental period because individuals diagnosed with psychiatric disorder during the adolescent period are rare, and their cases tend to be severe and involve substantial impairment.34 Adolescent diagnoses examined for this analysis included depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Adolescent anxiety disorders diagnosed under DSMIII comprised overanxious disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and phobias; the separate disorders were collapsed into one variable.30

Childhood behavioral problems. The Rutter Child Scales38 were administered at ages 5, 7, 9, and 11 years to assess major areas of each participant's behavioral and emotional functioning during the past year. Scales were completed separately by parents and teachers at each age. The relevant items were summed across the 4 ages to derive, separately for parents and teachers, measures indexing the study participants' behavior problems in different settings. These indices were then combined into one measure for each behavior problem. The 3 final measures included internalizing problems (e.g., worries about many things, often appears miserable, unhappy, tearful, and rather solitary), antisocial behavior problems (e.g., bullies other children, frequently fights with other children, often irritable, disobedient, tells lies, destroys own or others' belongings, and has stolen things on one or more occasions), and hyperactivity (e.g., very restless and hardly ever still, squirmy/fidgety, cannot settle into anything for more than a few moments, has poor concentration or short attention span). For ease of interpretation, each of the 3 measures was standardized.

Family History of Psychiatric Disorder

The Dunedin Study family history assessment has been described in detail elsewhere.39 The family history consisted of reports of psychiatric problems provided by study members and both parents for each study member's siblings, parents, and grandparents, using the Family History Screen.40 Here, we report family history for major depression, any anxiety disorder, conduct disorder/antisocial personality disorder (CD/ASPD), and alcohol abuse. The family history was summarized as the proportion of family members in the pedigree who ever had the disorder, adjusted to account for differences in genetic relatedness to the proband of first- and second-degree relatives. For ease of comparison across disorders, family history scores for each disorder were standardized.

Confounding Factors

We controlled for sex and childhood social class in all multivariate analyses. Study members' family social class in childhood was measured with a 6-point scale assessing parents' occupational status.41 Family social class is defined as the average of the highest occupational status level of either parent across study assessments from the study member's birth through 15 years (α = 0.92). To aid interpretation, we used standardized scores.

Statistical Analysis

We used Poisson regression with robust standard errors to model risk ratios estimating associations between lifetime psychiatric variables and adult insomnia. First, to establish the degree of concurrent comorbidity between insomnia and other disorders, we modeled the risk for insomnia associated with each age-38 psychiatric diagnosis. Unadjusted models in this analysis included no covariates; adjusted models controlled for sex and family social class.

We next assessed whether antecedent mental health problems (i.e., persistent psychiatric conditions in young adulthood, psychiatric conditions in adolescence, behavioral problems in childhood, and family history of disorder) predicted insomnia at age 38. In adjusted models for these analyses, we additionally controlled for psychiatric comorbidity at age 38. Concurrent psychiatric morbidity was defined using a single dichotomous covariate that indexed whether the study member received any of the following psychiatric diagnoses at age 38: depression, GAD, PTSD, any fear or phobia, alcohol dependence, cannabis dependence, or hard drug dependence.

Dose-response relationships between cumulative lifecourse psychiatric diagnoses and age-38 insomnia risk were estimated using an ordinal variable corresponding to number of diagnoses received between ages 11 and 38 (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4+ diagnoses with depression); again, Poisson regression with robust standard errors was used to model risk ratios for insomnia.

Lastly, we used interaction terms to test whether associations between earlier psychiatric history variables and age-38 insomnia differed for men and women. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp LP).

RESULTS

Prevalence of Insomnia at Midlife

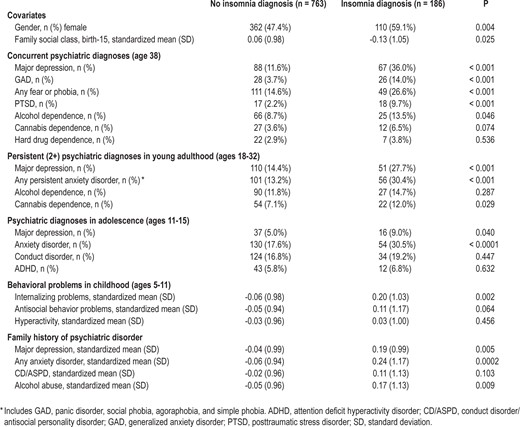

At age 38 years, 19.6% of Dunedin study members (n = 186) were diagnosed with insomnia. Study members with insomnia were more likely than their peers to be female (59.1% vs. 47.4%; χ2 = 8.18, P = 0.004); many also came from lower-class families (F1,942 = 5.02, P = 0.03). Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for study members with and without insomnia.

Sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric history variables in Dunedin study members with and without insomnia at age 38.

Sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric history variables in Dunedin study members with and without insomnia at age 38.

Concurrent Psychiatric Conditions at Age 38

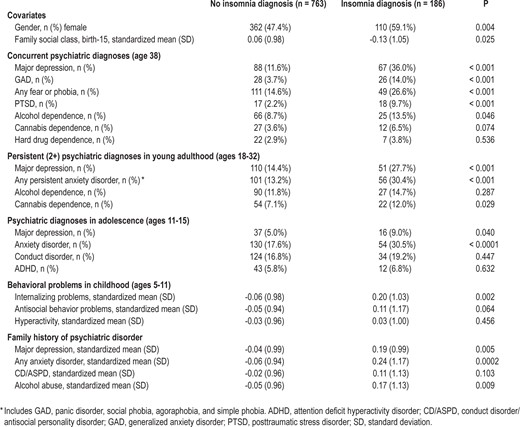

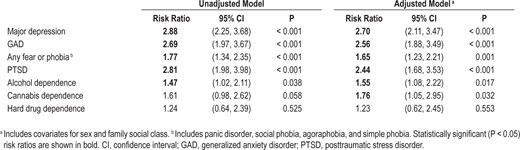

Table 2 shows relative risks between specific psychiatric diagnoses and insomnia, all at age 38. After adjustment for sex and family social class, study members with depression, GAD, fear/phobia, PTSD, alcohol dependence, or cannabis dependence (but not hard drug dependence) were significantly more likely than their peers to have insomnia. Moreover, study members with insomnia had substantially higher burdens of overall age-38 psychiatric morbidity (Figure 1). While fewer than 12% of those without insomnia met criteria for ≥ 2 concurrent psychiatric diagnoses, nearly 30% of insomniac individuals did so.

Insomnia diagnosis status and psychiatric comorbidity at age 38 years. Bars depict, among study members with age-38 insomnia (dark gray bars) and without age-38 insomnia (light gray bars), the percent with zero, one, two, or ≥ 3 concurrent psychiatric conditions (including major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, any fear or phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, alcohol dependence, cannabis dependence, and hard drug dependence).

Antecedent Mental Health Problems

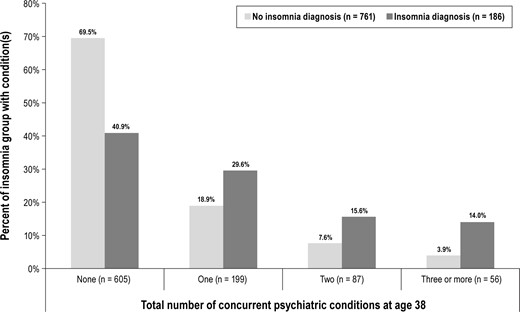

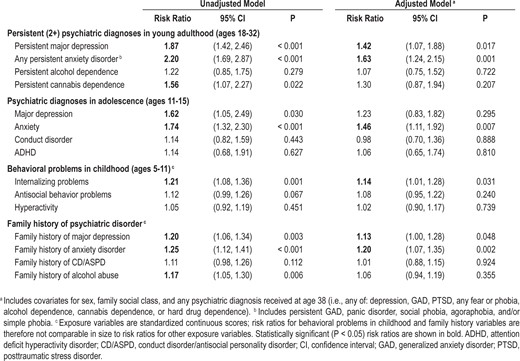

Table 3 shows relative risks between earlier mental health problems and age-38 insomnia.

Persistent psychiatric conditions in young adulthood (ages 18-32). Study members who had been persistently diagnosed with internalizing disorder as young adults were significantly more likely to have insomnia at early midlife. In models adjusted for sex, social class, and age-38 psychiatric comorbidity, young adults with persistent depression were approximately 40% more likely than their peers to have subsequent midlife insomnia, while young adults with persistent anxiety were 60% more likely to have insomnia. Persistent alcohol dependence did not predict subsequent insomnia. Moreover, although bivariate models suggested that young adults with persistent cannabis dependence were also at higher risk for insomnia, in adjusted models this association was attenuated and became nonsignificant.

Psychiatric conditions in adolescence (ages 11-15). We found that, in unadjusted models, adolescent study members diagnosed with internalizing disorder (depression or anxiety) appeared significantly more likely than their peers to have insomnia in early midlife. After adjusting for covariates, however, depressed adolescents no longer had elevated risk for insomnia. Anxiety remained a significant factor: Anxious adolescents were 46% more likely than their peers to be subsequently diagnosed with insomnia. Neither conduct disorder nor ADHD increased risk for age-38 insomnia.

Behavioral problems in childhood (ages 5-11). Childhood internalizing problems also foreshadowed study members' early midlife sleeping problems. Study members who were rated by their parents and teachers as prone to excessive worry, misery, and solitude were at significantly increased risk for insomnia; after adjusting for covariates, a 1-SD increase in these internalizing problems predicted a 14% increased risk of insomnia at age 38. Study member children with higher levels of antisocial behavior or hyperactivity evinced no excess risk for insomnia.

Family history of psychiatric disorder. In unadjusted models, we found that study members whose families had more severe histories of depression, anxiety, and alcohol dependence (but not CD/ASPD) were more likely to have insomnia in early midlife. In models adjusted for sex, social class, and age-38 psychiatric comorbidity, however, only family history of internalizing disorders conveyed excess risk for insomnia. Study members with 1-SD increases in familial depression and familial anxiety were, respectively, 13% and 20% more likely to have insomnia.

Role of Stability of Internalizing Problems

Thus far, we report that internalizing problems in young adulthood, adolescence, and childhood, as well as familial history of internalizing disorder, consistently predict insomnia at early midlife. Mental health problems—including internalizing disorder—exhibit considerable stability over the lifecourse.29,30 It might therefore seem inevitable that internalizing problems at different age periods will produce similar associations with later insomnia, simply because the same individuals have anxiety/depression at each age (as well as a higher likelihood of insomnia). However, additional analyses suggested that this was not the case in our study. Correlations between internalizing disorder measures at different ages were significant, but no correlation exceeded 0.26. This indicates substantial unshared variance between the variables across the years. Therefore, it was not simply the stability of internalizing symptoms over time that was responsible for our findings.

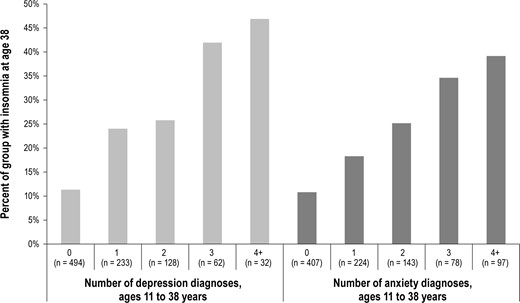

We also tested whether persistent internalizing disorder across the lifecourse, assessed using a variable that separately summed the number of depression and anxiety diagnoses received between adolescence and age 38, predicted early midlife insomnia (Figure 2). In analyses adjusting for sex, social class, and age-38 psychiatric comorbidity, each additional occasion that a study member was diagnosed with depression was associated with a 25% increased risk of insomnia (RR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.15, 1.36; P < 0.001); each additional anxiety diagnosis was associated with a 19% increased risk of insomnia (RR = 1.19; 95% CI = 1.10, 1.29; P < 0.001).

Dose-response relationships between lifecourse internalizing disorders and midlife insomnia. Bars depict percentage of study members diagnosed with insomnia at age 38 years, according to their number of lifetime diagnoses with depression (left-side, light gray bars) and anxiety (right-side, dark gray bars).

This dose-response effect was somewhat stronger among study members whose diagnosable depression episode or anxiety disorder began in adolescence (i.e., between ages 11 and 15 years). Among study members with early-onset depression, each additional depression diagnosis predicted a nearly 70% increased risk (RR = 1.68; 95% CI = 1.12, 2.53; P = 0.013) for later insomnia. Among those without early-onset depression, however, each additional depression diagnosis predicted only 28% increased risk for insomnia (RR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.14, 1.42; P < 0.0001). Similarly, among study members with early-onset anxiety, each additional anxiety diagnosis predicted a 28% increased insomnia risk (RR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.11, 1.47; P = 0.001); but for those individuals whose anxiety began later, each additional anxiety diagnosis was associated with only a 17% increase (RR = 1.17; 95% CI = 1.04, 1.32; P = 0.008) in insomnia risk.

Sex Differences, Adulthood Social Class, Medical Comorbidity, and Presence of an Infant in the Home

We tested whether any of the associations between psychiatric history variables and adulthood insomnia differed for men and women. Except for the association between concurrent PTSD and insomnia in Table 2 (P for interaction = 0.04), none of the sex interaction terms were statistically significant (all other P > 0.15). We also tested whether including a covariate for study members' age-38 socioeconomic status (based on their current or most recent occupation42) made a difference to the associations reported in Tables 2 and 3; results were unaffected.

Because physical health problems may also contribute to insomnia, we wanted to ascertain whether medical comorbidity played a role in our observed associations. To test this, we used a variable indexing how many serious chronic physical health conditions the study member reported at age 38 (mean = 0.48, SD = 0.67, range = 0 to 3). Health conditions included asthma, arthritis, cancer, Crohn disease, hepatitis C, lupus, multiple sclerosis, and obesity (defined as a body mass index ≥ 30). We then re-estimated each model in Tables 2 and 3 controlling for this covariate. Estimates were very slightly reduced in magnitude for some associations, but statistical inference was unaffected in all cases.

Lastly, we wanted to ensure that our results were not confounded by study members who had problems sleeping because of a young infant in the home. Many sleep studies recruit participants who have self-referred to a clinic because of severe problems with sleeping. In a community cohort, however, some false-positive cases of insomnia might arise from individuals with an infant who report sleeping problems. A total of 26 study members reported having an infant ≤ 6 months old at the time of the age-38 data collection (4.3% of study members with insomnia [n = 8]; 2.4% of those without insomnia [n = 18]). We re-estimated each model in Table 3 with an additional covariate indexing the presence of an infant; results were unchanged. Results also remained similar if we altered the infant age criteria to 15 or 24 months, by which point most infants sleep through the night.43

DISCUSSION

The results of this study provide evidence that individuals who struggle with lifecourse anxiety and depression are uniquely susceptible to insomnia in early midlife. Although we found in cross-sectional analyses that study members with both externalizing and internalizing disorders were more likely to report insomnia, when we examined these relationships developmentally (and controlled for the confounds of sex, social class, and age-38 concurrent psychiatric comorbidity), we found that insomnia risk was foreshadowed solely by study members' anxiety and depression. The link between prior internalizing disorder—as measured in young adulthood, adolescence, and childhood, and by familial history—and midlife insomnia was highly consistent, emerged early in life, and followed a dose-response pattern.

Methodological advantages of the study include its use of a representative birth cohort with good retention, a rigorous operational definition of insomnia,4 and our prospective measures of multiple mental health problems spanning nearly 40 years. The study was also strengthened by the inclusion of study members' family history of psychiatric disorder.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the reporting period for insomnia at age 38 was one month, whereas it was 12 months for the other disorders. It was therefore not possible to establish the temporal ordering of insomnia and concurrent psychiatric diagnoses at age 38. In addition, more detailed measures of our study members' sleep habits (such as sleep logs and overnight sleep studies), as well as information on the presence of sleep disorders such as narcolepsy or sleep apnea, were not available. We also found that 19.6% of the Dunedin study members met criteria for a past-month diagnosis of insomnia. This is higher than some previous estimates, in part due to different assessment methods. However, the prevalence of insomnia in our population-representative cohort was largely consistent with that found in samples of North American adults.1–3,44 Our definition of insomnia is in line with the insomnia diagnoses outlined by both DSM-IV and DSM-V, with the caveat that we inquired about sleep problems lasting at least one month (rather than three months as required by DSM-V) because this DSM-V criterion was established subsequent to our age-38 data assessment. Additionally, our insomnia assessment did not include queries about the frequency of insomnia episodes (e.g., number of episodes in the past year) or the age of onset of study members' insomnia symptoms. This would have required assessing long-term retrospective recall of symptoms, which has previously been found to be highly unreliable.34

The chicken-or-the-egg question of whether insomnia antedates psychiatric disorder or disorder antedates insomnia has long been under debate.8–10,14,45 Our paper cannot settle this debate because insomnia symptoms have not been regularly assessed alongside psychiatric disorders in prior waves of the Dunedin study. The study design to settle this question would entail contiguous annual assessments of both insomnia and mental disorders in a cohort as they age from childhood to midlife. However, it is our experience that neither funders nor research participants favor this approach. What our study contributes is the observation that the association emerges with the earliest childhood symptoms of disorder (and even goes back over two generations of family history of internalizing disorder), and that among psychiatric conditions, anxiety and depression are the most important to examine in future research.

Previous work has suggested that the most robust association between insomnia and psychological disorder is with depression,3,14,46 although strong longitudinal links between anxiety and sleep problems have also been reported.7,15,47 Our longitudinal analyses suggested that the magnitudes of the associations between midlife insomnia and lifecourse depression and anxiety were similar. It is possible that depression and anxiety predict insomnia for different reasons, but the overall similarity between the anxiety and depression findings is not surprising given the high degree of longitudinal comorbidity between these disorders and their many shared etiological factors.30,48,49

We found that histories of persistent alcohol or cannabis dependence in young adulthood were not associated with later insomnia. While the physiological effects of alcohol and cannabis appear to have an acute contemporaneous influence on sleep problems, and while sleep problems may predict subsequent relapse in recovering alcoholics,50,51 our study of early midlife adults suggests that alcohol and cannabis dependence are not aspects of individuals' lifecourse histories that need to be considered as predisposing to insomnia. It is possible, however, that as the cohort ages, a longitudinal bidirectional link between insomnia and alcohol dependence will emerge. However, insomnia does not consistently predict subsequent incidence of substance dependence, suggesting that the cross-sectional associations may be more important.52,53

Our findings have implications for understanding the etiology of insomnia. Disturbances in key physiological systems could underpin lifelong and intergenerational susceptibility to both internalizing disorders and sleep problems. Our finding that insomnia risk was especially high among individuals who had family history of internalizing disorder, as well as among those with an early-onset and persistent course of internalizing disorder, is consistent with this notion of shared genetic and biological susceptibility.54–56 Candidate physiological disturbances could include hyperarousal of neural, cardiac, metabolic, and/or neuroendocrine systems,57–60 and dysregulation of the noradrenergic or synaptic systems.61–63

Alternatively, it is also possible that the association between internalizing disorder across the lifecourse and midlife insomnia arises from cognitive and behavioral conditioning processes. For example, experiencing sleep difficulties in the context of a major depressive episode may alter an individual's later perceptions of his or her sleep environment, generating anticipatory anxious rumination and “learned sleep preventing associations”57 which can lead to chronic insomnia.64 Future research should further test these two hypotheses.

Lastly, our findings also have implications for treating insomnia in clinical populations and for ameliorating the public health burden due to insomnia. Clinically, our study adds to the evidence that adults suffering from insomnia are likely to have a history of depression and anxiety. This knowledge can help with clinicians' case conceptualization of people seeking treatment for insomnia. It also indicates that comorbid internalizing disorders may need to be treated in conjunction with the sleeping problems in order to best address patients' complaints. From a public health perspective, the high prevalence of insomnia observed among our study participants lends support to the conclusion that adulthood insomnia is a common and burdensome disorder in its own right.1,3,65 Given the significance of sleep difficulties for multiple areas of functioning, it may be worthwhile providing these individuals with information and skills—such as stress management interventions and sleep promotion techniques—that help prevent symptoms of insomnia. The recognition that individuals who experience persistent internalizing problems during development are at high risk for insomnia in later adulthood may also inform prevention strategies at the population level.

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 1733.

Comments