Published online Sep 22, 2014. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v4.i3.62

Revised: June 17, 2014

Accepted: July 12, 2014

Published online: September 22, 2014

AIM: To study the degree of stigmatization among trainee psychiatrists, individual characteristics potentially leading to higher associative stigma, and coping mechanisms.

METHODS: Two hundred and seven trainee psychiatrists in Flanders (Belgium), all member of the Flemish Association of Trainee Psychiatrists, were approached to participate in the survey. A non-demanding questionnaire that was specifically designed for the purpose of the study was sent by mail. The questionnaire consisted of three parts, each emphasizing a different aspect of associative stigma: devaluing and humiliating interactions, the focus on stigma during medical training, and identification with negative stereotypes in the media. Answers were scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The results were analyzed using SPSS Version 18.0.

RESULTS: The response rate of the study was 75.1%. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was good, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.71. Seventy-five percent of all trainee psychiatrists confirmed hearing denigrating or humiliating remarks about the psychiatric profession more than once. Additionally, more than half of them had had remarks about the incompetence of psychiatrists directed at them. Only 1.3% remembered having stigma as a topic during their psychiatric training. Trainees who had been in training for a longer period of time had experienced a significantly higher level of stigmatization than trainees with fewer years of experience (mean total stigma scores of 16.93 ± SD 7.8 vs 14.45 ± SD 6.1, t = -2.179 and P < 0.05). In addition, senior trainees effectively kept quiet about their profession significantly more often than their junior colleagues (mean item score 0.44 ± SD 0.82 vs 0.13 ± SD 0.48, t = 2.874, P < 0.01). Comparable results were found in trainees working in adult psychiatry as were found in those working in child or youth psychiatry (mean item score 0.38 ± SD 0.77 vs 0.15 ± SD 0.53, t = -2.153, P < 0.05). Biologically oriented trainees were more inclined to give preventive explanations about their profession, which can be seen as a coping mechanism used to deal with this stigma (mean item score 2.05 ± SD 1.05 vs 1.34 ± SD 1.1, t = -3.403, P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION: Associative stigma in trainee psychiatrists is underestimated. More attention should be paid to this potentially harmful phenomenon in training.

Core tip: Associative stigma is an extension of psychiatric stigma to those who care for patients, including psychiatrists. Scientific evidence on associative stigma among trainee psychiatrists is scarce although theoretical considerations are abundant. This study tried to evaluate the degree to which trainees experience stigmatization related to their profession. The results suggest that associative stigmatization is a marked problem for psychiatrists in training. Trainee psychiatrists in Flanders mention feelings of stigmatization within society in general and the medical environment in particular. A better understanding of this complex phenomenon is certainly warranted, to prevent the further evolution of the mental health gap.

- Citation: Catthoor K, Hutsebaut J, Schrijvers D, De Hert M, Peuskens J, Sabbe B. Preliminary study of associative stigma among trainee psychiatrists in Flanders, Belgium. World J Psychiatr 2014; 4(3): 62-68

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v4/i3/62.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v4.i3.62

Stigma is defined as a discrediting or disgracing mark[1-5], usually leading to negative behavior on the part of its bearer[6-10]. Different approaches have been used to conceptualize psychiatric stigma[1-5]. In his modified labeling theory, Link[1] states that labeling leads to higher vulnerability to relapse and that labeled people use coping strategies to avoid discrimination and low self-esteem. The definition and conceptualization of psychiatric stigma are still evolving. Aspects such as devaluation, discrimination, decreased self-esteem, self-restricted behavior, and dysfunctional coping are almost always mentioned[1-4]. Most studies have consistently reported that patients with psychotic disorders[7-12], affective disorders, and alcohol dependence[13] experience stigmatization as a serious hindrance in daily life.

Associative stigma is an extension of psychiatric stigma to those who care for patients, such as family members and mental healthcare workers, including psychiatrists[14,15]. Multiple factors may contribute to the substantial associative stigma among psychiatrists. Basic assumptions regarding psychiatric treatments vary. They may be viewed as helpful, questionably efficient, or harmful[16,17]. Moreover, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) still has a negative image[18], the effectiveness of psychotherapy is often highly overrated, and misconceptions regarding the negative effects of psychopharmacology are widespread[19]. Furthermore, the general public is largely unaware of the medical background of psychiatrists and the intensity and duration of their training; the portrayals of psychiatrists in the media, for example, in cartoons and movies[20,21], are mostly stereotypical and ridiculous, thus enhancing feelings of stigma.

The results regarding the perception of psychiatry among medical students are mixed[6]. Psychiatry is presumed to offer low job satisfaction and low respect and prestige as compared to other medical disciplines. Psychiatry is also criticized because of the vagueness of its diagnoses and lack of a solid scientific foundation[22]. Medical students are often confronted with negative remarks about the emotional instability of psychiatrists[23], and they are rarely encouraged to consider psychiatry as a career option[24]. Nevertheless, it is the responsibility of academic instructors to prepare all kinds of physicians for dealing with psychiatric patients[25].

Scientific data on associative stigma among psychiatrists are lacking. However, Gaebel[26,27] presented unpublished data on this topic at the 15th World Congress of the World Psychiatric Association, in 2011. His preliminary results indicate that psychiatrists perceive their stigma more intensely than general practitioners and more frequently report stigmatizing experiences, as well as the need to fight stigmatization. Moreover, the reasons psychiatrists remain in the psychiatric profession appear to be mainly idealistic: improving the psychic wellbeing of their patients, without considering the negative effects of the profession (lower income as compared to other specialists and associative stigma). In addition, a high level of work experience seems to be linked with a low level of stigma perceptions, few discrimination experiences, low burnout rates, and high job satisfaction.

To the best of our knowledge, scientific evidence on the extent of associative stigma among trainee psychiatrists is very scarce. On the other hand, theoretical considerations of this issue are abundant. Therefore, the main aim of the current exploratory, cross-sectional research is to evaluate the degree to which trainee psychiatrists experience stigmatization related to their profession. We also wanted to determine whether specific individual characteristics of trainees can lead to higher levels of associative stigma and which coping mechanisms are prominent.

A total of 207 trainee psychiatrists were approached to participate in this survey. They were all members of the Flemish Association of Trainees in Psychiatry [Vlaamse Vereniging van Assistenten Psychiatrie (VVAP)], an association that keeps records of all trainee psychiatrists in Flanders. Psychiatry training in Flanders requires 5 years of intensive internship under the supervision of an approved senior resident. At least 2 years of the training are fulfilled in a university center, most of which are urban. Peripheral internships are usually rural. Internships provide complementary experience with biological psychiatry, neurology or internal medicine, and psychotherapy. It is worth noting that junior trainees in Flanders are in their first two years of training, with an age span between 25 to 27 years. At the end of their training, their mean age is 30 years, although the ages of the trainee psychiatrists were not included in the socio-demographical part of the study.

Associative stigma was conceptualized as the combined effects of three stigma-related experiences: (1) the frequency and intensity of devaluing and humiliating interactions with significant others generally and within the medical circle in particular[7]; (2) the degree to which psychiatric stigma was a focus of attention during medical and psychiatric training[6]; and (3) the level of identification with negative stereotypes in the media[21].

Because no questionnaires were available for measuring associative stigma among psychiatrists[10] at the time of this survey, we designed one for the specific purpose of this study. Our newly developed questionnaire contained an adaptation of existing instruments, as well as de novo constructed items. The particular stigmatization questionnaire that we used in this survey was composed of 21 questions about stigma from three perspectives. Ten questions were about subjective experiences of humiliation and devaluation and the resulting coping mechanisms[7,15]. This first 10-item section of the questionnaire is an amended version of the Family Interview Schedule (FIS) of the World Health Organization (1992). This interview was developed as a structured instrument for associative stigma among family members of psychiatric patients in order to evaluate the perception of psychiatric problems by others in the patients’ environment and the consequences for both the patient and his or her family (Sartorius and Janca, 1996)[28]. The following six items on the list were paraphrased from the FIS questionnaire for relatives to suit the situational context of trainees: “tendency to conceal”, “secretiveness”, “fear of being avoided or ignored”, “explanation”, “fear over hesitation to marry into the family” and “contact with others”. The following six questions of the questionnaire were about stigma during medical and psychiatric training and were based on topics found in the international literature on stigmatizing experiences of psychiatrists[6,10]. The final five questions were about stereotypical images of psychiatry and psychiatrists in the media[21]. This third part of the questionnaire was based on Pies’s article “Psychiatry in the Media: The Vampire, The Fisher King and the Zaddik” (2001). This article describes how psychiatrists are portrayed in popular films via a number of fixed stereotypes: the evil genius, the crazy doctor, and the miraculous healer. Four of these stereotypes based on characters from well-known films were described in the questionnaire (four items). The last question on the list asked whether trainees were ever subjected to comments about the film One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest when they suggested ECT. Currently, the negative image of this treatment and of psychiatry as a whole is strongly emphasized.

The questionnaire was not particularly demanding and took 10 min to complete. The answers were scored on a Likert scale ranging from “never” (0 points) to “once” (1 point) to “more than once” (2 points) to “often” (3 points). The overall level of stigmatization (total associative stigma) was defined as the sum of the points scored by all the answers given by a single respondent, with a minimum of 0 points and a maximum of 63 points.

A cover letter describing the aim of the study and informed consent, as well as the questionnaire, were sent to all members listed in the Flemish Association of Trainee Psychiatrists (VVAP), an association that keeps record all trainees psychiatrist in Flanders. The ethical committee of the University Center Sint-Jozef Kortenberg gave permission to conduct the survey. The recruitment of trainees took place in a uniform way. The cover letter described the aim of the research and stressed the importance of the anonymous collection of data. In a second mailing, which was sent out two months later, the trainees who had not yet replied to the original survey were again asked to fill in the questionnaire and send it back.

The results were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A student t-test was used to compare the average total associative stigmatization scores of the different subgroups of trainee psychiatrists. The subgroups were composed of independent socio-demographic and educational variables.

In total, 151 of 201 participants (six letters were returned as undeliverable) completed and returned the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 75.1%. The descriptive data of the population of trainee psychiatrists are reported in Table 1. There was a major gender gap in the participating trainees: 49 were male, and 102 were female (67.5%). This corresponds to the male/female ratio of all trainee psychiatrists in Flanders. More than 4 in 5 of the respondents (85.4%) were in a steady relationship at the time, whereas 14.6% were single. Also, 54.3% of trainees taking part in the investigation were senior assistants. Thus, they had more experience in clinical practice. The remaining 45.7% were either first-year or second-year trainees. Of all trainees questioned, 62.9% practiced adult psychiatry, 35.8% practiced child and youth psychiatry, and 1.3% practiced both. A slight majority of trainee psychiatrists (59.6%) had a predominantly psychotherapeutic orientation, 24.5% had a biological orientation, and 12.6% had both. A large number of all trainees had somatic, neurological or liaison experience (66.9%) in addition to their psychiatric experience, whereas only 33.1% had worked exclusively in psychiatric settings.

| n = 151 | |

| Gender | |

| Male/Female | 49 (32.5)/102 (67.5) |

| Position in training | |

| Junior/Senior | 69 (45.7)/82 (54.3) |

| Relationship | |

| Single/Steady relationship | 22 (14.6)/129 (85.4) |

| Type of training | |

| Adult/Children and adolescents | 95 (62.9)/54 (35.8) |

| Both | 2 (1.3) |

| Orientation in training | |

| Biological/Psychotherapeutical | 42 (24.5)/90 (59.6) |

| Both | 19 (12.6) |

| Experience in training | |

| Somatic, neurological, or liaison/Just clinical psychiatry | 101 (66.9)/50 (33.1) |

The Cronbach’s α of the questionnaire used in this investigation was 0.71, showing sufficient internal consistency.

The mean total stigma score (sum of all scores on the individual items) among our large cohort of trainee psychiatrists was 15.8 (SD ± 7.2). The most striking results were the following: 114 trainee psychiatrists (75.5%) claimed to have had denigrating or humiliating remarks about the psychiatric profession directed at them more than once. Also, 98 of them (65%) had had remarks about the incompetence of psychiatrists directed at them, typically related to psychiatrists not being real doctors, and 105 trainees psychiatrists (66.3%) had not been taken seriously by colleagues because of the nature of their profession. Among respondents, 74 (49%) had received discouraging remarks from tutors in university about their career choice. Only seven (1.3%) of these young doctors remembered stigma as a topic during their psychiatric training. In addition, 112 (74.2%) of the trainees had felt stigmatized as psychiatrists within the professional medical environment, although only 43 (28.5%) of them had ever considered a career switch. Questions about cinematic psychiatrist stereotypes showed no significant results. Only the stereotype of the crazy psychiatrist was mentioned by 57 trainees (37.7%). The full results of the stigmatization questionnaire are presented in Table 2.

| Never | Once | > Once | Often | |

| Humiliating remarks about the profession | 24 (15.9) | 13 (8.6) | 87 (57.6) | 27 (17.9) |

| Humiliating remarks about the profession toward family members | 115 (7.1) | 9 (6.0) | 27 (17.2) | 1 (0.7) |

| Ever considered keeping quiet about the profession | 121 (80.1) | 4 (2.6) | 23 (15.2) | 3 (2.0) |

| Ever kept your profession quiet for others | 126 (83.4) | 6 (4.0) | 18 (11.9) | 1 (0.7) |

| Messages about psychiatrists as “not real doctors” | 53 (35.1) | 17 (11.3) | 70 (46.4) | 11 (7.3) |

| Not taken seriously by colleagues because of profession | 46 (30.5) | 12 (7.9) | 65 (43.0) | 28 (18.5) |

| Patient refused to talk to you | 72 (47.7) | 16 (10.6) | 57 (37.7) | 6 (4.0) |

| Ever given an explanation about the profession | 42 (27.9) | 9 (6.0) | 62 (41.1) | 38 (25.2) |

| Ever considered a change of career | 108 (71.5) | 9 (6.0) | 30 (19.9) | 4 (2.6) |

| Warned partner about marrying a psychiatrist | 123 (81.5) | 9 (6.0) | 18 (11.9) | 1 (0.7) |

| Ever discussed the importance of stigmatization with colleagues | 65 (43.0) | 18 (11.9) | 59 (39.1) | 9 (6.0) |

| Stigmatization mentioned during medical training | 138 (91.4) | 2 (1.3) | 9 (6.0) | 2 (1.3) |

| Stigmatization mentioned during psychiatric training | 144 (95.4) | 5 (3.3) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Discouraging remarks from tutors at university | 77 (51.0) | 27 (17.9) | 40 (26.5) | 7 (4.6) |

| Felt stigmatized within the professional medical circle | 39 (25.8) | 24 (15.9) | 69 (45.7) | 19 (12.6) |

| Felt stigmatized within society as a whole | 69 (45.7) | 15 (9.9) | 55 (36.4) | 12 (7.9) |

| Archetype vampire | 126 (83.4) | 13 (8.6) | 12 (7.9) | 0 (0) |

| Archetype fisher king | 126 (83.4) | 14 (9.3) | 11 (7.3) | 0 (0) |

| Archetype zaddik | 137 (90.7) | 8 (5.3) | 6 (4.0) | 0 (0) |

| Archetype crazy psychiatrist | 94 (62.3) | 17 (11.3) | 35 (23.2) | 5 (3.3) |

| Negative image of ECT in movies | 98 (64.9) | 16 (10.6) | 27 (17.9) | 10 (6.6) |

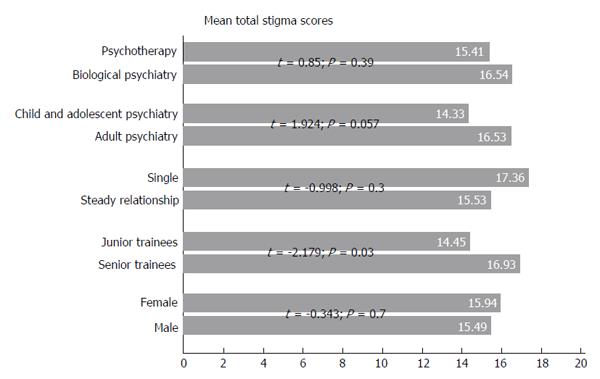

There were no significant differences in mean total stigma scores between male and female trainees (15.49 ± SD 7.9 vs 15.94 ± SD 6.8, t = -0.343 and P > 0.05) or between those who were single and those in steady relationships (17.36 ± SD 8.1 vs 15.53 ± SD 7.0, t = -0.998 and P > 0.05). No differences were found between trainees with a biological orientation and those with a psychotherapeutic background (mean total stigma scores of 16.54 ± SD 6.7 vs 15.41 ± SD 7.0, t = 0.85 and P > 0.05). There was a borderline significant difference between those working with adults and those working with children and adolescents (mean total stigma scores of 16.53 ± SD 7.7 vs 14.33 ± SD 6.0, t = 1.924, P = 0.057). Trainees who had been in training for a longer period of time had experienced a significantly higher level of stigmatization than trainees with fewer years of experience (mean total stigma scores of 16.93 ± SD 7.8 vs 14.45 ± SD 6.1, t = -2.179 and P < 0.05, Figure 1).

The most interesting results revealed on the analysis of the individual coping items on the questionnaire were the following: senior trainees kept quiet about their profession significantly more often than their junior colleagues (mean item score 0.44 ± SD 0.82 vs 0.13 ± SD 0.48, t = 2.874, P < 0.01). Comparable results were found among trainees working in adult psychiatry vs those working in child or youth psychiatry (mean item score 0.38 ± SD 0.77 vs 0.15 ± SD 0.53, t = -2.153, P < 0.05). Biologically oriented trainees were more inclined to give preventive explanations regarding their profession (mean item score 2.05 ± SD 1.05 vs 1.34 ± SD 1.1, t = -3.403, P < 0.01) than those who were more psychotherapeutically oriented. The level of feelings of incompetence in comparison to colleagues working in somatic medicine was marginally higher bur not statistically significant among female trainee psychiatrists than among male trainees (mean item score 1.24 ± SD 1.15 vs 1.62 ± SD 1.08), and the same applied to more senior trainees vs junior trainees (mean item score 1.66 ± SD 1.05 vs 1.3 ± SD 1.17). Significantly more male trainees than female trainees reported being refused by patients during a consultation simply because of their psychiatric profession (mean item score 1.24 ± SD 1.01 vs 0.85 ± SD 0.99, t = 2.246, P < 0.05), whereas the number of biologically oriented trainee psychiatrists who were refused was only marginally higher but not statistically significant than the number of trainee psychotherapists (mean item score 1.32 ± SD 1.1 vs 0.94 ± SD 0.95). Female trainee psychiatrists felt significantly more stigmatized within the professional category of medical doctors than their male counterparts (mean item score 1.2 ± SD 1.02 vs 0.84 ± SD 1.03, t = -2.020, P < 0.05), and the same was true for those who had more years of training compared to junior trainees (mean item score 1.28 ± SD 1.03 vs 0.87 ± SD 0.1, t = 2.337, P < 0.05).

The current study aimed to explore associative stigma among trainee psychiatrists that was related to their professional background. Recent findings from a survey by Gaebel[26,27] show substantially more associative stigma in psychiatrists in various countries all over the world as compared with family practitioners. The results of our study suggest that associative stigmatization is also a marked problem for young psychiatrists in training. Although it is clear that mental illness stigmatization primarily concerns patients and their family members and much should be done to support them in handling this burden, patients also suffer due to the negative image of psychiatrists and the hospitals they work for.

Indeed, trainee psychiatrists in Flanders mentioned feelings of stigmatization within society in general and the medical environment in particular. There is no reason to believe that the results would be different in the French-speaking part of Belgium. The psychiatric training and socio-demographic backgrounds of the trainees are comparable in both regions.

According to the stigma theory of Link[2], a trainee psychiatrist is labeled only because of his or her choice of profession, resulting in negative connotations that ultimately lead to devaluation. This is also supported by the framework of Thornicroft et al[4], in which ignorance of or misinterpretations about the nature and duration of the training of psychiatrists, as well as prejudices about the helpfulness of therapeutic interventions and the vagueness of the job content, are supposedly responsible for associative stigma, at least in part.

Furthermore, trainees who have been in training for a longer period of time experience a significantly higher level of stigmatization than their junior counterparts. This could suggest that stigmatization during the training of psychiatrists is dynamic, with an increasing impact as training proceeds. One possible explanation is the accumulation of devaluating experiences with colleagues, patients, family members, and authority figures during training, together with a lack of support, attention, and understanding on the part of trainers and supervisors. Accordingly, in senior trainees and younger psychiatrists, the accumulating associative stigma seems to fade with time. Some caution is warranted regarding this interpretation because all data have been assessed cross-sectionally and cohort effects cannot be excluded. Although almost 30% of the trainees had considered a career switch at some point, it is not clear whether this has a causal relationship with associative stigma. According to Gaebel[26,27], psychiatrists who consider leaving their profession do so merely because of financial and working conditions, not because of stigma. Thus, further research is needed to better understand this remarkable dynamic tendency of associative stigma in psychiatrists.

The most frequently used coping mechanism in trainees is providing a preventive explanation of their profession. The need to explain the content of the work done in psychiatry is rooted in its generally dubious reputation and could be interpreted as a kind of defense against expected rejection by patients, family members, or colleagues. There is some danger that trainee psychiatrists may be isolated from their colleagues in somatic medicine. Such isolation could prevent the provision of adequate mental healthcare, especially when colleagues in somatic medicine hesitate to make referrals due to prejudice. Hence, a more optimal integration of psychiatric and somatic care could improve the care that we give our patients.

Only a very small minority of trainees remembered that stigmatization in mental healthcare workers was explicitly mentioned during psychiatric training. The problem of stigmatization and its influence on the subjective feeling of well-being seems to be underestimated in university and training hospitals. Although efforts have been made to correct this, it may still result in an even greater diminishment of the number of candidates for mental healthcare in the population of medical students (the so-called mental health gap), which is already visible in several countries, including Belgium[22,29]. Therefore, it could be useful to begin anti-stigma campaigns during medical training in order to avoid a decrease in the number of candidate psychiatrists. The limited technical aspects of the psychiatric profession make the job vulnerable in actual medical practice, in which strict empirical standards rule the daily routine. We also suggest that trainers and supervisors carefully listen to and deal with the doubts, devaluing experiences, and signs of burnout of their trainees.

Our study is limited because we lacked a control group and we used a non-validated questionnaire. However, no appropriate questionnaire was available when we designed the study[10]. Very recently, Gaebel et al[29] published a new validated questionnaire with items about perceived stigma, stereotype agreement, perceived structural discrimination, attitudes toward the profession, discrimination experiences, and stigma outcomes. Our questionnaire and that of Gaebel et al[29] share several items. Future research will certainly aim to validate the questionnaire in our study as well. Moreover, a comparison between the current data and a control group of medical colleagues will be needed to better understand the associative stigma phenomenon. The current study’s strengths are the large study cohort and the high response rate.

In conclusion, the current study clearly demonstrates the presence of substantial feelings of associative stigma in trainee psychiatrists. A better understanding of this complex and multidimensional phenomenon is certainly warranted.

The authors thank the University Centre Sint-Jozef’s support staff for their assistance with survey distribution to the trainee psychiatrists and data collection.

Stigma is defined as a discrediting or disgracing mark, usually leading to negative behavior on the part of its bearer. Different approaches have been used to conceptualize psychiatric stigma, and are still evolving. Aspects such as devaluation, discrimination, decreased self-esteem, self-restricted behavior, and dysfunctional coping are almost always mentioned. Associative stigma is an extension of psychiatric stigma to those who care for patients, such as family members and mental healthcare workers, including psychiatrists. Multiple factors may contribute to the substantial associative stigma among psychiatrists: wrong basic assumptions on psychiatric treatments and limited awareness on the intensity and duration of psychiatry training.

Scientific data on associative stigma among psychiatrists are very scarce, although theoretical considerations are abundant. Scientific evidence on the extent of associative stigma among trainee psychiatrists is lacking in the current literature. There are reasons to believe that medical students are negatively influenced by associative stigma to make the choice for psychiatry as a career. Given the mental health gap, a continuing diminishing number of trainees worldwide would have devastating effects on mental health care in the future.

Trainee psychiatrists in Flanders mention feelings of stigmatization within society in general and the medical environment in particular. Associative stigmatization is thus a marked problem for young psychiatrists in training. They are labeled only because of their choice of profession, resulting in negative connotations that ultimately lead to devaluation. Besides, they develop coming mechanisms to deal with it. This might have a devastating impact not only on their wellbeing, but finally on decreasing number of candidates in psychiatry training.

The problem of stigmatization and its influence on the subjective feeling of well-being seems to be underestimated in university and training hospitals. More efforts have to be made to correct this. It could also be useful to begin anti-stigma campaigns during medical training in order to avoid a decrease in the number of candidate psychiatrists. The authors also suggest that trainers and supervisors carefully listen to and deal with the doubts, devaluing experiences, and signs of burnout of their trainees.

Associative stigma is an extension of psychiatric stigma to those who care for patients, such as family members and mental healthcare workers, including psychiatrists. The mental health care gap is the diminishment of the number of candidates for mental healthcare in the population of medical students. Coping mechanisms are conscious psychological adaptations to environmental stress, in order to obtain more comfort.

This study addresses a critical issue in professional training and clinical practice in the psychiatric field. The article has an important place as starting point for research into the area of stigmatization of trainee psychiatrists, as it made clear that the phenomenon is underestimated and impacts the mental health care gap.

P- Reviewer: Kleinfelder J, Muneoka K, Tcheremissine OV S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Link B, Struening E, Cullen F, Shrout P, Dohrenwend B. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. Am Sociol Rev. 1989;54:400-423. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Link B, Phelan J. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363-385. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Corrigan P. On the stigma of mental illness. Practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, D.C. : American Psychological Association 2005; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A, Sartorius N. Stigma: ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:192-193. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 430] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 371] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, Rowlands OJ. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:4-7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 898] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 798] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sartorius N, Gaebel W, Cleveland HR, Stuart H, Akiyama T, Arboleda-Flórez J, Baumann AE, Gureje O, Jorge MR, Kastrup M. WPA guidance on how to combat stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:131-144. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Phillips MR, Pearson V, Li F, Xu M, Yang L. Stigma and expressed emotion: a study of people with schizophrenia and their family members in China. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:488-493. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 178] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fung KM, Tsang HW, Corrigan PW. Self-stigma of people with schizophrenia as predictor of their adherence to psychosocial treatment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;32:95-104. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373:408-415. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 709] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 652] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, Thornicroft G. Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice and discrimination: a review of measures. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:80. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 233] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sibitz I, Amering M, Unger A, Seyringer ME, Bachmann A, Schrank B, Benesch T, Schulze B, Woppmann A. The impact of the social network, stigma and empowerment on the quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:28-33. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 144] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lysaker PH, Yanos PT, Outcalt J, Roe D. Association of stigma, self-esteem, and symptoms with concurrent and prospective assessment of social anxiety in schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2010;4:41-48. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. “A disease like any other”? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1321-1330. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 684] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 585] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Phelan JC, Bromet EJ, Link BG. Psychiatric illness and family stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:115-126. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 249] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shibre T, Negash A, Kullgren G, Kebede D, Alem A, Fekadu A, Fekadu D, Madhin G, Jacobsson L. Perception of stigma among family members of individuals with schizophrenia and major affective disorders in rural Ethiopia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:299-303. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 156] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kobau R, Diiorio C, Chapman D, Delvecchio P. Attitudes about mental illness and its treatment: validation of a generic scale for public health surveillance of mental illness associated stigma. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:164-176. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Hamre P, Dahl A, Malt U. Public attitudes to the quality of psychiatric treatment, psychiatric patients, and prevalence of mental disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 1994;48:275-281. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Mental health literacy as a function of remoteness of residence: an Australian national study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:92. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Jorm AF. Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:396-401. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 973] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 863] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gabbard G, Gabbard K. Cinematic stereotypes contributing to the stigmatization of psychiatrists. Stigma and mental illness. Washington, D.C. : American Psychiatric Press, Inc 1992; 113-126. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Pies R. Psychiatry in the media: The vampire, the fisher king, and the zaddik. J Mund Beh. 2001; Available from: http: //www.mundanebehavior.org/issues/v2n1/pies.htm. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Brockington I, Mumford D. Recruitment into psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:307-312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Buchanan A, Bhugra D. Attitude of the medical profession to psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:1-5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Holmes D, Tumiel-Berhalter LM, Zayas LE, Watkins R. “Bashing” of medical specialties: students’ experiences and recommendations. Fam Med. 2008;40:400-406. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Xavier M, Almeida JC. Impact of clerkship in the attitudes toward psychiatry among Portuguese medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:56. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gaebel W. Stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatrists: Results of an international study. 2011;18-22. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Gaebel W. Stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatrists: Results of an international study. 2011;. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Sartorius N, Janca A. Psychiatric assessment instruments developed by the World Health Organization. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31:55-69. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gaebel W, Zäske H, Cleveland HR, Zielasek J, Stuart H, Arboleda-Florez J, Akiyama T, Gureje O, Jorge MR, Kastrup M. Measuring the stigma of psychiatry and psychiatrists: development of a questionnaire. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261 Suppl 2:S119-S123. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |