Published online Jan 27, 2018. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i1.51

Peer-review started: August 23, 2017

First decision: December 4, 2017

Revised: December 7, 2017

Accepted: December 29, 2017

Article in press: December 29, 2017

Published online: January 27, 2018

To investigate clinical, etiological, and prognostic features in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who were followed-up from 2001 to 2011 were included in the study. The diagnosis was established by histopathological and/or radiological criteria. We retrospectively reviewed clinical and laboratory data, etiology of primary liver disease, imaging characteristics and treatments. Child-Pugh and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage was determined at initial diagnosis. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was done to find out treatment effect on survival. Risk factors for vascular invasion and overall survival were investigated by multivariate Cox regression analyses.

Five hundred and forty-five patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were included in the study. Viral hepatitis was prevalent and 68 patients either had normal liver or were non-cirrhotic. Overall median survival was 16 (13-19) mo. Presence of extrahepatic metastasis was associated with larger tumor size (OR = 3.19, 95%CI: 1.14-10.6). Independent predictor variables of vascular invasion were AFP (OR = 2.95, 95%CI: 1.38-6.31), total tumor diameter (OR = 3.14, 95%CI: 1.01-9.77), and hepatitis B infection (OR = 5.37, 95%CI: 1.23-23.39). Liver functional reserve, tumor size/extension, AFP level and primary treatment modality were independent predictors of overall survival. Transarterial chemoembolization (HR = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.28-0.51) and radioembolization (HR = 0.36, 95%CI: 0.18-0.74) provided a comparable survival benefit in the real life setting. Surgical treatments as resection and transplantation were found to be associated with the best survival compared with loco-regional treatments (log-rank, P < 0.001).

Baseline liver function, oncologic features including AFP level and primary treatment modality determines overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Core tip: Hepatocellular carcinoma is a leading cause of cancer-related death with curative treatment options limited to orthotopic liver transplantation, surgical resection and local ablation. Our study confirmed that liver functional reserve, tumor extension and alfa-fetoprotein level are among the most important determinants of patient survival. Survival benefit of non-curative treatments including transarterial chemoembolization and Yttrium-90 radioembolization remains an area of uncertainty. In this study we showed that transarterial chemoembolization and Yttrium-90 radioembolization provided a significant and comparable survival benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the real-life setting. We concluded that primary modality of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma is a major determinant of patient survival that should be incorporated while estimating prognosis.

- Citation: Ekinci O, Baran B, Ormeci AC, Soyer OM, Gokturk S, Evirgen S, Poyanli A, Gulluoglu M, Akyuz F, Karaca C, Demir K, Besisik F, Kaymakoglu S. Current state and clinical outcome in Turkish patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2018; 10(1): 51-61

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v10/i1/51.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i1.51

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is among the most frequently diagnosed cancers worldwide, and it comprises 70%-85% of all primary liver malignancies[1]. HCC is a leading cause of cancer-related death in the world, which is estimated to be more than 600000 deaths per year[2]. A unique characteristic of HCC is that most patients have liver cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis. Even in the absence of liver cirrhosis, HCC almost always develops within the spectrum of a chronic liver disease[3]. A variety of important risk factors for the development of HCC have been identified including but not limited to hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, hereditary hemochromatosis, and cirrhosis of almost any cause[3]. Etiological risk factors associated with the development of HCC are also important due to their relationship with their implications for treatment and prognosis of the disease. In addition to these etiological factors, tumor related factors including histological grade, size and number of nodules, and patient related factors as age, severity of underlying liver cirrhosis and performance status of the patient play a crucial role in determining the outcome of the disease[4]. Therefore, several prognostic scoring systems were developed to predict the prognosis for patients with HCC, and to individualize treatment by matching best therapeutic option with the patient who is most likely to benefit. Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification which is the most widely used system, comprises four stages that are based on the number and size of nodules, vascular invasion and extrahepatic metastasis, Child-Pugh score (CPS) and performance status of the patient[5]. BCLC system also provides a treatment algorithm to be applied for each stage in patients with HCC. Nevertheless, there are still many problems in determining disease prognosis and selecting patients for appropriate treatment. No classification is completely satisfactory as a result of many other risk factors, including tumor histology, serum alfa-fetoprotein (AFP) level, presence of variant estrogen receptors and diabetes mellitus, which also influence patient survival. Besides, primary treatment modality, which is among the most important determinants of patient outcome, has not been evaluated as a prognostic indicator in relation to other determinants of survival.

Despite the advances in screening, diagnosis and treatment of HCC, a substantial amount of patients are diagnosed at a later stage of the disease which may preclude curative treatment options. Therefore, novel strategies to facilitate early diagnosis and a better estimation of prognosis are needed to improve patient survival. In the present study, we investigated clinical, etiological, and prognostic features in our large, single center cohort of patients with HCC who were diagnosed, treated and followed-up in the last decade. Primary objective of the study was to define potential factors that have influence on prognosis, specifically to determine survival benefit associated with primary treatment modality of HCC in a real life setting. Secondary objective of the study was to find out the relationship between pre-diagnosis screening characteristics, clinical stage of the disease at diagnosis and overall survival.

Patients with HCC who were followed-up in the Department of Gastroenterohepatology, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University between January 2001 and August 2011 were included in this single center, retrospective cohort study. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and it was approved by the ethics committee of Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University. The diagnosis of HCC was based on the recommendations reported by the EASL panel of experts in 2001[6]. According to these recommendations; the diagnosis was established by histopathological and/or radiological criteria. CPS was calculated at baseline in cirrhotic patients as previously described[7]. BCLC stage was determined in every patient with HCC at initial diagnosis according to the extent of tumor, performance status, CPS, vascular invasion and extrahepatic spread[5]. We reviewed demographic, clinical and staging characteristics, laboratory data, etiology of primary liver disease, imaging characteristics and treatments of HCC patients. Number and size of nodules, total tumor diameter (TTD), type of tumor (single nodule, multinodular or diffuse-infiltrative), presence of major vascular involvement and extrahepatic metastasis were determined according to baseline imaging records. Survival data of all patients were updated as of November 2011.

All patients with a suspicion of primary liver cancer were evaluated by clinical, laboratory and imaging studies including a 4-phase computerized tomography (CT) scan or dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The diagnosis was made if there were radiologic hallmarks of HCC as arterial hypervascularity and venous/late phase wash out. In the absence of radiologic hallmarks of HCC or if findings were inconsistent on contrast enhanced CT or MRI, a biopsy was obtained and assessed by an expert hepatopathologist. Extrahepatic metastasis was screened by a contrast-enhanced chest CT and whole-body bone scan.

All patients with a diagnosis of HCC had baseline physical examination, and results of standard laboratory investigations including complete blood count, renal and liver function tests, screening tests for hepatitis viruses (hepatitis B surface antigen-HBsAg, hepatitis B core antibody-anti-HBc total and hepatitis C antibody-anti-HCV) and AFP. If HBsAg or anti-HCV was detected to be positive further tests [HBeAg, anti-HBe, HBVDNA (PCR), and anti-Delta total (plus HDVRNA when positive) or HCVRNA, respectively] were obtained. Most patients with HCC already had a diagnosis of a chronic liver disease, and remaining patients with unrecognized liver disease had undergone detailed evaluations to assess the presence of other etiologies including alcoholic liver disease, hemochromatosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and autoimmune liver diseases. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed to evaluate the presence of esophageal or gastric varices in each patient.

Treatment of HCC was guided by BCLC classification, however most patients were listed for OLT using the expanded criteria after 2001 as previously described[8]. Treatment options included surgical resection, OLT, percutaneous ablation (RFA or ethanol/acetic acid ablation), TACE, Yttrium-90 radioembolization and systemic therapy using sorafenib. Curative partial hepatectomy was performed in patients with tumors confined to one lobe of the liver that shows no radiographic evidence of invasion of the hepatic vasculature, no evidence of portal hypertension and adequate liver functional reserve. All candidates for surgical resection underwent indocyanine green test to determine operative risk before hepatectomy. Percutaneous ablation was selected in patients who did not meet resectability criteria and had a single tumor ≤ 3 cm in diameter. Patients without a suitable living-donor were listed for OLT. Listed patients who had an anticipated time to OLT more than 6 mo underwent percutaneous ablation, TACE or Yttrium-90 radioembolization decided by physician’s discretion according to tumor characteristics and hepatic reserve. Patients with advanced stage HCC who were not candidates for curative treatments underwent TACE, Yttrium-90 radioembolization or sorafenib therapy. In terminal stage, patients were followed-up under natural course with best supportive care.

Twenty-seven patients were suitable for hepatic resection and underwent surgery. Twelve patients who had 1 or 2 small (≤ 3 cm) nodules underwent percutaneous ablation with RFA, and 5 patients with a single nodule ≤ 2 cm underwent percutaneous acetic acid/ethanol injection. Two-hundred and sixty-seven patients who were ineligible for surgical resection or percutaneous ablation, but had tumor characteristics that are compatible with expanded criteria were listed for OLT. A total of 56 patients (47 within expanded criteria) with HCC underwent OLT during the follow-up period, due to the shortage of cadaveric organs or unavailability of a suitable living donor. The number of patients who underwent TACE was 172. Among them 90 patients underwent 1 session, 53 patients underwent 2 sessions, and 29 patients underwent ≥ 3 sessions of TACE. The distribution of treatment modalities in the remaining patients were as follows: 19 patients underwent Yttrium-90 radioembolization, 16 patients received systemic therapy with sorafenib, and 238 patients received no treatment until the end of the follow-up. Treatment characteristics of patients with HCC were summarized in Table 1.

| Treatment modality | Pts within expanded criteria, n (%) | Pts within Milan criteria, n (%) | Total, n | BCLC stage | Survival, n (%) | |||

| 0-A | B | C | D | |||||

| Surgical resection | 24 (89) | 19 (70) | 27 | 18 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 16 (59) |

| OLT | 47 (84) | 41 (73) | 56 | 24 | 13 | 7 | 12 | 56 (100) |

| Percutaneous ablation | 16 (94) | 15 (88) | 17 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 10 (59) |

| TACE | 118 (69) | 99 (58) | 172 | 81 | 47 | 34 | 10 | 80 (46) |

| Yttrium-90 | 11 (58) | 10 (53) | 19 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 10 (53) |

| Sorafenib | 3 (19) | 2 (13) | 16 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 8 (50) |

| No treatment | 88 (37) | 61 (26) | 238 | 24 | 28 | 54 | 132 | 39 (16) |

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (range) while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (%). Differences between frequencies were evaluated using Pearson χ2 or Fisher’s exact test when necessary. Predictor variables of vascular invasion and extrahepatic metastasis were investigated by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Univariate Cox regression analyses were performed to find out factors associated with overall survival of patients with HCC. Variables which showed a significant influence (P < 0.05) were included in a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model to find out independent prognostic factors that affect overall survival. The results of the model were presented as a hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We performed Kaplan-Meier analyses to determine cumulative survival probabilities and treatment effect on overall survival. Log-rank test was used for the statistical comparison of Kaplan-Meier curves. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS v20 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A two tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 545 patients (449 male, mean age 59.5 ± 10) with HCC who were diagnosed and followed-up between January 2001 and August 2011 were included in the study. The diagnosis of HCC was established by CT or MRI in 459 patients, and the remaining patients underwent liver biopsy due to inconsistent findings in radiological examinations. The number of patients with underlying chronic liver disease was 532, 13 (2.3%) patients had normal liver without any identifiable risk factor for the development of HCC. 350 (66%) of patients with chronic liver disease were already aware of their underlying liver disease at the time of the diagnosis of HCC. However, only 110 patients (31.4%) were under regular follow-up with a combined use of scheduled liver ultrasonography and AFP measurement. The mean estimated duration of chronic liver disease was 69 ± 60 mo (range, 3-420 mo).

The number patients according to underlying etiology for chronic liver disease were as follows: 287 patients with chronic HBV, 120 patients with chronic HCV, 37 patients with chronic delta hepatitis, 10 patients with co-infection of HBV and HCV, 39 patients with cryptogenic liver disease, 21 patients with alcoholic liver disease, 10 patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, 5 patients with autoimmune liver disease, 2 patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome and 1 patient with hemochromatosis. Among patients with chronic viral hepatitis, there were 24 patients who had significant alcohol consumption (> 210 g/wk) which may contribute to the severity of underlying liver disease. The majority of patients with chronic liver disease had cirrhosis at different stages (CPS A, 247 patients; CPS B, 140 patients; CPS C, 90 patients), and 68 patients (12.5%) were pre-cirrhotic based on clinical and/or histopathological examinations. Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

| Characteristics | |

| Number of patients (%) | 545 (100) |

| Male, n (%) | 449 (82) |

| Female, n (%) | 96 (18) |

| Age (yr) | |

| Mean ± SD | 59.5 ± 10 |

| Median (range) | 60 (19-85) |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 532 (97.6) |

| Chronic viral hepatitis, n (%) | 454 (83.3) |

| HBV (monoinfection) | 287 (52.6) |

| HCV (monoinfection) | 120 (22) |

| Hepatitis D | 37 (6.7) |

| HBV + HCV co-infection | 10 (1.8) |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 477 (87.5) |

| Child A | 247 (45.3) |

| Child B | 140 (25.7) |

| Child C | 90 (16.5) |

| Diagnostic method for HCC, n (%) | |

| CT | 26 (4.8) |

| MRI | 433 (79.4) |

| Liver biopsy | 86 (15.8) |

| Treatment, n (%) | |

| No treatment | 238 (43.7) |

| Hepatic resection | 27 (5) |

| OLT | 56 (10.3) |

| TACE | 172 (31.5) |

| Yttrium-90 radioembolization | 19 (3.5) |

| RFA | 12 (2.2) |

| Ethanol/acetic acid ablation | 5 (0.9) |

| Sorafenib | 16 (2.9) |

The number of patients with a single tumor was 333 (61%), and the remaining patients had multinodular (191 patients, 35%) or diffuse HCC (21 patients, 3.9%). Median AFP level was 62 ng/mL (range, 1-223169 ng/mL), and 241 (44.2%) patients had an AFP level > 100 ng/mL. At the time of the diagnosis, the number of patients within Milan and expanded criteria were 247 (45%) and 307 (56%), respectively. The distribution of patients according to BCLC classification was as follows: BCLC 0, 14 patients (2.6%); BCLC A, 152 patients (27.9%); BCLC B, 105 patients (19.2%); BCLC C, 115 patients (21.1%); BCLC D, 159 patients (29.2%). Extrahepatic metastasis and macroscopic vascular invasion were diagnosed in 26 (4.8%) and 37 (6.8%) patients, respectively. The only predictor variable for the presence of extrahepatic metastasis at initial diagnosis was TTD (TTD ≥ 5 cm; OR = 3.19, 95%CI: 1.14-10.6, P = 0.029). Stage of liver disease, tumor type, HBV infection, number of nodules, presence of vascular invasion and AFP level did not predict extrahepatic metastasis (Table 3). Univariate logistic regression analyses showed that HBV infection, multinodular and diffuse-infiltrative HCC, TTD, and AFP level were associated with vascular invasion at initial diagnosis of HCC. At multivariate analysis, independent predictor variables of vascular invasion were found to be AFP > 200 ng/mL (OR = 2.95, 95%CI: 1.38-6.31, P = 0.005), TTD > 5 cm (OR = 3.14, 95%CI: 1.01-9.77, P = 0.047) and HBV infection (OR = 5.37, 95%CI: 1.23-23.39, P = 0.025) (Table 4).

| Univariate | |||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Total tumor diameter | |||

| ≥ 5 cm | 3.19 | 1.18-8.59 | 0.022 |

| Tumor type | |||

| Solitary HCC | Reference | - | - |

| Multinodular HCC | 1.17 | 0.52-2.66 | 0.71 |

| Diffuse-infiltrative HCC | 1.06 | 0.13-8.43 | 0.96 |

| Vascular invasion | 1.86 | 0.53-6.51 | 0.33 |

| HBV infection | 1.76 | 0.73-4.26 | 0.21 |

| Number of nodules | 1.21 | 0.92-1.59 | 0.18 |

| Stage of liver disease | |||

| Normal or precirrhotic liver | Reference | - | - |

| Child-Pugh A | 2.29 | 0.51-10.2 | 0.28 |

| Child-Pugh B | 1.22 | 0.23-6.47 | 0.81 |

| Child-Pugh C | 1.14 | 0.19-7.01 | 0.89 |

| AFP level | |||

| > 100 ng/mL | 1.30 | 0.59-2.85 | 0.52 |

| > 200 ng/mL | 1.59 | 0.72-3.50 | 0.25 |

| > 400 ng/mL | 1.48 | 0.64-3.39 | 0.36 |

| > 1000 ng/mL | 1.91 | 0.81-4.52 | 0.14 |

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| TTD ≥ 5 cm | 6.56 | 2.29-18.79 | < 0.001 | 3.14 | 1.01-9.77 | 0.047 |

| Tumor type | ||||||

| Solitary HCC | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Multinodular HCC | 2.07 | 1.01-4.25 | 0.047 | 1.54 | 0.72-3.30 | 0.270 |

| Diffuse-infiltrative HCC | 6.63 | 2.14-20.51 | 0.001 | 2.71 | 0.82-8.94 | 0.100 |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 1.86 | 0.53-6.51 | 0.330 | |||

| Etiology of liver disease | ||||||

| Hepatitis C | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Hepatitis B | 6.29 | 1.48-26.76 | 0.013 | 5.37 | 1.23-23.39 | 0.025 |

| Other (non-viral) | 4.52 | 0.89-22.91 | 0.069 | 3.76 | 0.72-19.74 | 0.120 |

| Stage of liver disease | ||||||

| Normal or precirrhotic liver | Reference | - | - | |||

| Child-Pugh A | 0.60 | 0.24-1.53 | 0.290 | |||

| Child-Pugh B | 0.53 | 0.18-1.52 | 0.240 | |||

| Child-Pugh C | 0.62 | 0.20-1.94 | 0.420 | |||

| AFP level | ||||||

| > 100 ng/mL | 3.77 | 1.79-7.96 | < 0.001 | |||

| > 200 ng/mL | 4.18 | 2.05-8.52 | < 0.001 | 2.95 | 1.38-6.31 | 0.005 |

| > 400 ng/mL | 2.81 | 1.43-5.52 | 0.003 | |||

| > 1000 ng/mL | 3.54 | 1.78-7.05 | < 0.001 | |||

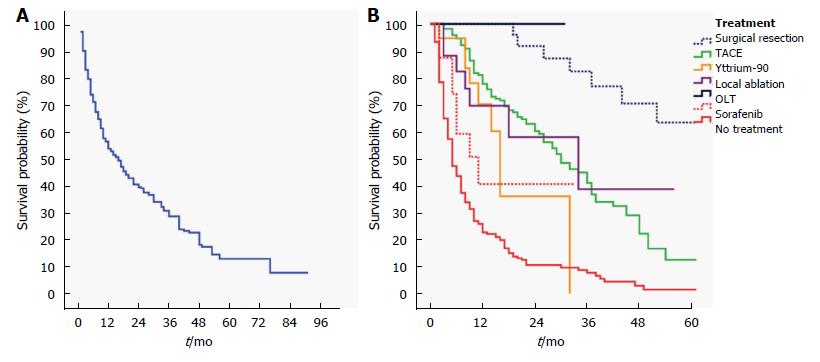

Cumulative overall median survival was 16 (13-19) mo in the whole cohort (Figure 1A). The best survival outcome was achieved in patients with HCC who underwent surgical treatments as OLT and hepatic resection (HR = 0.07, 95%CI: 0.04-013, P < 0.001, Figure 1B). Treatment modalities including TACE, Yttrium-90 radioembolization, RFA were also found to be associated with improved overall survival (Table 5). Sorafenib therapy demonstrated a survival benefit, yet with a borderline significance. Univariate Cox regression analyses showed that tumor related factors associated with overall survival of patients with HCC were TTD, tumor-type, vascular invasion, extrahepatic metastasis, and AFP level (Table 5). Patient-related factors including age and gender did not have significant influence on overall survival, yet stage of liver disease significantly predicted overall survival. HBV (HR = 1.28, 95%CI: 0.98-1.66, P = 0.074) and non-viral etiologies (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.002-1.989, P = 0.049) were found to have a borderline influence on patient survival compared to HCV. In multivariate Cox proportional hazard model, stage of liver disease, tumor-related factors including TTD, vascular invasion, extrahepatic metastasis, and AFP level retained significance regarding their influence on overall survival. Treatments including OLT/hepatic resection, RFA, TACE, and Yttrium-90 radioembolization were independently associated with improved overall survival). TACE and Yttrium-90 radioembolization provided a comparable survival benefit (Table 5).

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Patient related factors | ||||||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.360 | |||

| Gender | 0.82 | 0.60-1.10 | 0.180 | |||

| Etiology of liver disease | ||||||

| Hepatitis C | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Hepatitis B | 1.28 | 0.98-1.66 | 0.074 | 0.98 | 0.74-1.30 | 0.900 |

| Other (non-viral) | 1.41 | 1.002-1.99 | 0.049 | 1.12 | 0.78-1.60 | 0.540 |

| Stage of liver disease | ||||||

| Normal or precirrhotic liver | Reference | - | - | Reference | - | - |

| Child-Pugh A | 1.52 | 0.99-2.30 | 0.051 | 1.29 | 0.84-1.99 | 0.250 |

| Child-Pugh B | 3.16 | 2.04-4.88 | < 0.001 | 1.81 | 1.13-2.89 | 0.013 |

| Child-Pugh C | 10.46 | 6.57-16.66 | < 0.001 | 5.35 | 3.24-8.83 | < 0.001 |

| Tumor related factors | ||||||

| Total tumor diameter ≥ 5 cm | 3.07 | 2.40-3.93 | < 0.001 | 1.74 | 1.30-2.33 | < 0.001 |

| Multinodular or diffuse-infiltrative | 2.02 | 1.61-2.53 | < 0.001 | 1.23 | 0.95-1.59 | 0.120 |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 2.53 | 1.63-3.93 | < 0.001 | 2.17 | 1.37-3.45 | 0.001 |

| Vascular invasion | 3.48 | 2.42-5.01 | < 0.001 | 2.74 | 1.84-4.06 | < 0.001 |

| AFP level > 200 ng/mL | 2.59 | 2.07-3.23 | < 0.001 | 2.19 | 1.72-2.80 | < 0.001 |

| Treatment modalities vs no treatment | ||||||

| Surgical treatments (OLT, hepatic resection) | 0.07 | 0.04-0.13 | < 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.06-0.24 | < 0.001 |

| TACE | 0.24 | 0.19-0.31 | < 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.28-0.51 | < 0.001 |

| Yttrium-90 adioembolization | 0.37 | 0.19-0.72 | 0.003 | 0.36 | 0.18-0.74 | 0.005 |

| RFA | 0.12 | 0.04-0.38 | < 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.05-0.57 | 0.004 |

| Ethanol/acetic acid ablation | 0.60 | 0.22-1.63 | 0.318 | 0.79 | 0.28-2.22 | 0.660 |

| Sorafenib | 0.51 | 0.25-1.04 | 0.063 | 0.52 | 0.25-1.10 | 0.088 |

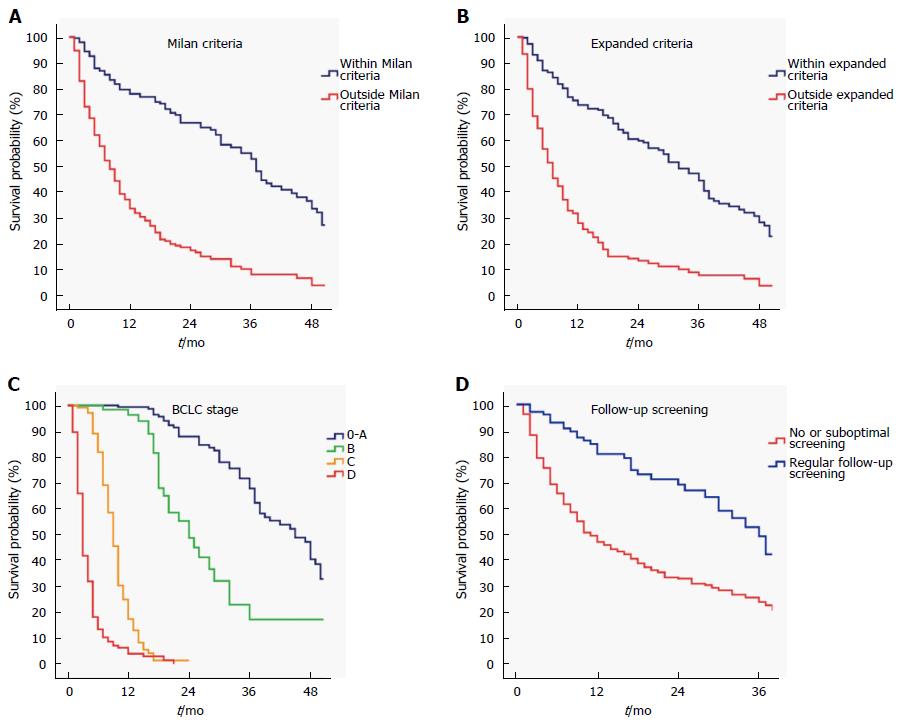

Among patients with chronic liver disease (532 patients), regular follow-up screening for HCC was performed in 110 (21%) patients. The remaining patients either were not aware of the underlying liver disease or did not have adequate access to health care services due to social, economic or cultural issues. Patients who had regular follow-up and screening with AFP-ultrasonography were diagnosed at an earlier BCLC stage (stage 0-A; 63/110, 57% vs 135/422, 32%, P < 0.001). The number of patients within Milan (69/110, 63% vs 177/422, 42%, P < 0.001) and expanded criteria (85/110, 77% vs 220/422, 52%, P < 0.001) was significantly higher in patients who underwent regular screening follow-up compared to patients who did not. Patients within Milan or expanded criteria, patients who were diagnosed at earlier BCLC stages and patients who had regular follow-up screening for HCC had a significantly better survival (Figure 2; log-rank, P < 0.001).

In this retrospective, single center, observational cohort study, we investigated possible risk factors including patient, tumor and treatment-related determinants of overall survival in patients with HCC. Most patients had cirrhosis and viral etiologies, especially HBV infection, were prevalent in our cohort. Two-third of patients with chronic liver disease was aware of their liver condition, and only one-third of them were under regular surveillance for early diagnosis of HCC. Implementation of regular surveillance was associated with diagnosis at earlier stages of HCC, in which curative treatments were amenable. Approximately, a half of the cohort was suitable for OLT according to Milan or expanded criteria, but only a minority of those patients could undergo OLT due to cadaveric organ shortage and absence of a suitable living donor.

In the present study we evaluated patient, tumor and treatment-related prognostic factors associated with overall survival by univariate and multivariate analyses. Among patient-related factors only the stage of liver disease was found to be associated with overall survival. Age, gender and etiology of liver disease did not predict mortality in multivariate analysis. Except, HBV infection was independently associated with vascular invasion in our study, which is consistent with the earlier reports showing a more aggressive and infiltrative behavior[9], and more frequent vascular invasion in HBV-related HCC[10]. However, the role of liver disease etiology in determining prognosis of patients with HCC is controversial. There are a number of studies with conflicting results. In an early study, HBV-related HCC was shown to have a poor prognosis compared with HCV-related tumors, which becomes statistically significant only in patients with advanced HCC[11]. In this study, patients underwent surgery (OLT or resection) and loco-regional (ablation or TACE) treatments or received no therapy. In another study, patients with HCV infection were reported to have a higher cumulated recurrence rate after hepatic resection for small HCC (≤ 3 cm) than in patients with HBV infection. In a subsequent study by Bozorgzadeh et al[12], HCV-positive and negative patients who underwent OLT were retrospectively reviewed, and HCV infection was found to have a negative impact on tumor-free and overall survival. Franssen et al[13] similarly found that survival and recurrence rates after both OLT and resection were better in HBV than in HCV-related HCC. There are also other studies confirming that HCV infection has a bad influence on overall and disease-free survival if a curative surgical treatment is applied[14-18]. Contrarily, the results of cohort studies which included HCC patients treated with loco-regional (RFA, TACE, etc.) modalities or best supportive care, either demonstrated no relationship between etiology and prognosis or showed a slightly negative influence on survival in HBV-related HCC[11,19-21]. In the era of regular surveillance, early diagnosis can suppress the effect of etiology in determining prognosis of HCC.

Our results were consistent with previous reports proving the association between tumor burden/extension and mortality. Total tumor size predicted mortality independent from the number of nodules which may suggest the up to 3 nodules criteria is too strict for selection of OLT candidates. This concept was also highlighted in recent studies showing combination of total tumor volume and AFP are better criteria to increase the number of OLT candidates with an acceptable post-transplant tumor-free survival[22,23]. Other tumor-related factors including extrahepatic metastasis and vascular invasion were also found to be independent prognostic factors.

AFP cannot be considered a sensitive diagnostic marker having a reported sensitivity of 60% when 20 ng/mL is chosen as a cut-off value for the diagnosis of HCC[24]. However, it can provide important prognostic implications even in different patient and treatment settings. Serum AFP level at presentation was clearly shown to correlate with tumor size and extent[25]. There is also substantial relationship between tumor growth and rise in serum AFP level[26]. In the present study, significantly elevated AFP level (> 100 ng/mL) was detected in less than half of the cohort, but it was found to be an independent predictor of both vascular invasion and mortality. Interestingly, we did not find any relationship between serum AFP level and presence of extrahepatic metastasis at diagnosis. Extrahepatic metastasis was only associated with total tumor diameter. To date, a number of studies indicated that AFP level is associated with overall and recurrence-free survival in HCC patients who received OLT[27] or underwent surgical resection[13,28-30]. With this regard, a model including AFP level in addition to Milan criteria was suggested recently by Duvoux et al[31] to improve patient selection for OLT in HCC. AFP can also be used to guide treatment decision in patients with early-stage HCC. In a study by Ebara et al[26], risk factors for exceeding the Milan criteria and overall survival after successful RFA in patients with early-stage HCC were investigated. It was reported that an AFP level higher than 100 ng/mL and local recurrence within 1 year of initial successful RFA were associated with earlier recurrence and overall survival. In a subsequent study by Suh et al[32], it was shown that the combination of AFP and prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II can be a useful marker to select patients with high recurrence risk after RFA for early-stage HCC (< 3 cm).

There are several other studies that investigated predictors of survival in patients undergoing curative and non-curative therapies[11,19,33-35]. The common finding among all studies is that tumor volume/extension, baseline liver function and serum AFP level are independent predictors of prognosis, which are also confirmed by our results. However, primary mode of treatment was not appropriately included in the multivariate analysis in any of those studies. In our study, we showed that liver functional reserve, tumor extension, and baseline AFP level influences overall survival regardless of the primary treatment modality, which is another decisive factor for survival in patients with HCC. Therefore, it should be incorporated into the clinical decision making for the selection of initial treatment option. Our study showed that the choice among initial treatment options has an utmost importance that substantially influence prognosis of patients with HCC. In the present study, surgical treatments and RFA were found to be far better than other loco-regional treatments and systemic therapy with sorafenib. Ethanol/acetic acid ablation was not associated with any survival benefit. TACE and Yttrium-90 radioembolization performed similar efficacy which is demonstrated by comparable hazard ratios after adjustment of confounding factors. Systemic treatment with sorafenib was associated with a survival advantage at a borderline significance compared with no treatment, which can be explained by low number of patients receiving systemic therapy.

In conclusion, surgical treatments and RFA are best options to achieve optimal survival rates in the long-term, and there is still a need for improvement of current surveillance methods for earlier detection of HCC to facilitate those curative treatments for most of the patients. Instead of being a diagnostic marker, baseline AFP level should be considered as a prognostic marker to identify those patients with dismal prognosis. Primary treatment modality of HCC should be considered as a prognostic indicator and should be taken into account while estimating overall survival.

HCC is a leading cause of cancer-related death with curative treatment options limited to orthotopic liver transplantation, surgical resection and local ablation. Several prognostic scoring systems were developed to predict the prognosis for patients with HCC, and to individualize treatment by matching best therapeutic option with the patient who is most likely to benefit. Nevertheless, no classification is completely satisfactory because of many other risk factors which also influence patient survival.

Primary treatment modality, which must be among the most important determinants of patient outcome, has not been evaluated as a prognostic indicator in relation to other determinants of survival until now. Therefore, the authors investigated the association between established prognostic factors of HCC and treatment to show how chosen treatment modality affects the prognosis.

Primary objective of the study was to define potential factors that have influence on prognosis, specifically to determine survival benefit associated with primary treatment modality of HCC in a real-life setting. Secondary objective of the study was to find out the relationship between pre-diagnosis screening characteristics, clinical stage of the disease at diagnosis and overall survival.

In the present study, the authors investigated clinical, etiological, and prognostic features in a large, single-center cohort of patients with HCC who were diagnosed, treated and followed-up in the last decade. The diagnosis was established by histopathological and/or radiological criteria that was based on the recommendations reported by the EASL panel of experts in 2001. The authors reviewed demographic, clinical and staging characteristics, laboratory data, etiology of primary liver disease, imaging characteristics and treatments of HCC patients. Number and size of nodules, total tumor diameter (TTD), type of tumor, presence of major vascular involvement and extrahepatic metastasis were determined according to baseline imaging records. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to find out factors associated with overall survival of patients with HCC.

A total of 545 patients with HCC who were diagnosed and followed-up between January 2001 and August 2011 were included in the study. Predictor variables of vascular invasion and extrahepatic metastasis were investigated by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. The authors showed that HBV infection, multinodular and diffuse-infiltrative HCC, TTD, and AFP level were associated with vascular invasion at initial diagnosis of HCC. At multivariate analysis, independent predictor variables of vascular invasion were found to be AFP > 200 ng/mL, TTD > 5 cm and HBV. The only predictor variable for the presence of extrahepatic metastasis at initial diagnosis was TTD. Stage of liver disease, tumor type, HBV infection, number of nodules, presence of vascular invasion and AFP level did not predict extrahepatic metastasis. The best survival outcome was achieved in patients with HCC who underwent surgical treatments as OLT and hepatic resection. Treatment modalities including TACE, Yttrium-90 radioembolization, RFA were also found to be associated with improved overall survival. Ethanol/acetic acid ablation was not associated with any survival benefit. Systemic treatment with sorafenib was associated with a survival advantage at a borderline significance compared with no treatment, which can be explained by low number of patients receiving systemic therapy. Patients who had regular follow-up and screening with AFP-ultrasonography were diagnosed at an earlier BCLC stage and had a significantly better survival.

It has been known that liver functional reserve, tumor extension and alfa-fetoprotein level are among the most important determinants of patient survival. The authors showed that in addition to patient and tumor related factors, initial choice of treatment is a strong and independent predictor of survival. Survival benefit of non-curative treatments including transarterial chemoembolization and Yttrium-90 radioembolization has been an area of uncertainty. Transarterial chemoembolization and Yttrium-90 radioembolization provided a significant and comparable survival benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the real-life setting.

Primary modality of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma is a major determinant of patient survival that should be incorporated while estimating prognosis in the future trials evaluating benefits of investigational new drugs.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Heo J, Yao HR S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45:529-538. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1764] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1760] [Article Influence: 97.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25175] [Article Influence: 1936.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Sherman M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, surveillance, and diagnosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:3-16. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 287] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Prognostic indicators in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of 72 studies. Liver Int. 2009;29:502-510. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 261] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329-338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2645] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2715] [Article Influence: 108.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, Christensen E, Pagliaro L, Colombo M, Rodés J; EASL Panel of Experts on HCC. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421-430. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646-649. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394-1403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1594] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1583] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Benvegnù L, Noventa F, Bernardinello E, Pontisso P, Gatta A, Alberti A. Evidence for an association between the aetiology of cirrhosis and pattern of hepatocellular carcinoma development. Gut. 2001;48:110-115. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Shijo H, Okazaki M, Koganemaru F, Higashi M, Sakaguchi S, Okumura M. Influence of hepatitis B virus infection and age on mode of growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1991;67:2626-2632. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Cantarini MC, Trevisani F, Morselli-Labate AM, Rapaccini G, Farinati F, Del Poggio P, Di Nolfo MA, Benvegnù L, Zoli M, Borzio F, Bernardi M; Italian Liver Cancer (ITA. LI.CA) group. Effect of the etiology of viral cirrhosis on the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:91-98. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bozorgzadeh A, Orloff M, Abt P, Tsoulfas G, Younan D, Kashyap R, Jain A, Mantry P, Maliakkal B, Khorana A. Survival outcomes in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma, comparing impact of hepatitis C versus other etiology of cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:807-813. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Franssen B, Alshebeeb K, Tabrizian P, Marti J, Pierobon ES, Lubezky N, Roayaie S, Florman S, Schwartz ME. Differences in surgical outcomes between hepatitis B- and hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of a single North American center. Ann Surg. 2014;260:650-656; discussion 656-658. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang YH, Wu JC, Chen CH, Chang TT, Lee PC, Chau GY, Lui WY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Comparison of recurrence after hepatic resection in patients with hepatitis B vs. hepatitis C-related small hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus endemic area. Liver Int. 2005;25:236-241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li Q, Li H, Qin Y, Wang PP, Hao X. Comparison of surgical outcomes for small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B versus hepatitis C: a Chinese experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1936-1941. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sasaki Y, Yamada T, Tanaka H, Ohigashi H, Eguchi H, Yano M, Ishikawa O, Imaoka S. Risk of recurrence in a long-term follow-up after surgery in 417 patients with hepatitis B- or hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;244:771-780. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Roayaie S, Haim MB, Emre S, Fishbein TM, Sheiner PA, Miller CM, Schwartz ME. Comparison of surgical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B versus hepatitis C: a western experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:764-770. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Utsunomiya T, Shimada M, Kudo M, Ichida T, Matsui O, Izumi N, Matsuyama Y, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Ku Y. A comparison of the surgical outcomes among patients with HBV-positive, HCV-positive, and non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide study of 11,950 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;261:513-520. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 100] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Trevisani F, Magini G, Santi V, Morselli-Labate AM, Cantarini MC, Di Nolfo MA, Del Poggio P, Benvegnù L, Rapaccini G, Farinati F, Zoli M, Borzio F, Giannini EG, Caturelli E, Bernardi M; Italian Liver Cancer (ITA. LI.CA) Group. Impact of etiology of cirrhosis on the survival of patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma during surveillance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1022-1031. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen PH, Kao WY, Chiou YY, Hung HH, Su CW, Chou YH, Huo TI, Huang YH, Wu WC, Chao Y. Comparison of prognosis by viral etiology in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:263-273. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Yang JD, Kim WR, Park KW, Chaiteerakij R, Kim B, Sanderson SO, Larson JJ, Pedersen RA, Therneau TM, Gores GJ. Model to estimate survival in ambulatory patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:614-621. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Toso C, Trotter J, Wei A, Bigam DL, Shah S, Lancaster J, Grant DR, Greig PD, Shapiro AM, Kneteman NM. Total tumor volume predicts risk of recurrence following liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1107-1115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 188] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Toso C, Meeberg G, Hernandez-Alejandro R, Dufour JF, Marotta P, Majno P, Kneteman NM. Total tumor volume and alpha-fetoprotein for selection of transplant candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective validation. Hepatology. 2015;62:158-165. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 197] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Trevisani F, D’Intino PE, Morselli-Labate AM, Mazzella G, Accogli E, Caraceni P, Domenicali M, De Notariis S, Roda E, Bernardi M. Serum alpha-fetoprotein for diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease: influence of HBsAg and anti-HCV status. J Hepatol. 2001;34:570-575. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Tangkijvanich P, Anukulkarnkusol N, Suwangool P, Lertmaharit S, Hanvivatvong O, Kullavanijaya P, Poovorawan Y. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis based on serum alpha-fetoprotein levels. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:302-308. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Ebara M, Ohto M, Shinagawa T, Sugiura N, Kimura K, Matsutani S, Morita M, Saisho H, Tsuchiya Y, Okuda K. Natural history of minute hepatocellular carcinoma smaller than three centimeters complicating cirrhosis. A study in 22 patients. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:289-298. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Hakeem AR, Young RS, Marangoni G, Lodge JP, Prasad KR. Systematic review: the prognostic role of alpha-fetoprotein following liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:987-999. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hanazaki K, Kajikawa S, Koide N, Adachi W, Amano J. Prognostic factors after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatitis C viral infection: univariate and multivariate analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1243-1250. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 89] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang CC, Iyer SG, Low JK, Lin CY, Wang SH, Lu SN, Chen CL. Perioperative factors affecting long-term outcomes of 473 consecutive patients undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1832-1842. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 120] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhang Q, Shang L, Zang Y, Chen X, Zhang L, Wang Y, Wang L, Liu Y, Mao S, Shen Z. α-Fetoprotein is a potential survival predictor in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with hepatitis B selected for liver transplantation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:544-552. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Duvoux C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Decaens T, Pessione F, Badran H, Piardi T, Francoz C, Compagnon P, Vanlemmens C, Dumortier J. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model including α-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:986-994.e3; quiz e14-15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 635] [Article Influence: 52.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Suh SW, Lee KW, Lee JM, You T, Choi Y, Kim H, Lee HW, Lee JM, Yi NJ, Suh KS. Prediction of aggressiveness in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma for selection of surgical resection. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1219-1224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Grieco A, Pompili M, Caminiti G, Miele L, Covino M, Alfei B, Rapaccini GL, Gasbarrini G. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with early-intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing non-surgical therapy: comparison of Okuda, CLIP, and BCLC staging systems in a single Italian centre. Gut. 2005;54:411-418. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 197] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | op den Winkel M, Nagel D, Sappl J, op den Winkel P, Lamerz R, Zech CJ, Straub G, Nickel T, Rentsch M, Stieber P. Prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Validation and ranking of established staging-systems in a large western HCC-cohort. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45066. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lee YH, Hsu CY, Hsia CY, Huang YH, Su CW, Lin HC, Chiou YY, Huo TI. A prognostic model for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria undergoing non-transplant therapies, based on 1106 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:551-559. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |