Using Visual Arts to Encourage Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder to Communicate Their Feelings and Emotions ()

1. Introduction

This paper reports the findings of a Bachelor of Education Honours thesis conducted in one Australian University and completed in 2016. The aim of the research was to tell in-depth stories of the lives of two children living with Autism and the ways in which their Art making impacted on the communication of their feelings and emotions.

Initially the inspiration for this research is presented, along with a brief review of pertinent literature, an outline of the methodological approach taken, and the parameters for the ethical collection of data. As data, including detailed observations of eleven Art making sessions, and many dozens of photos of participant Art works, were so extensive, it is not possible to present these in their entirety here. Rather, data from five selected sessions, those with the most powerful observations of participants and their associated Art works, are presented and discussed here. These data and the broader findings of the research are subsequently reflected upon and discussed.

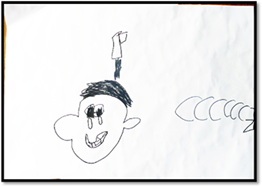

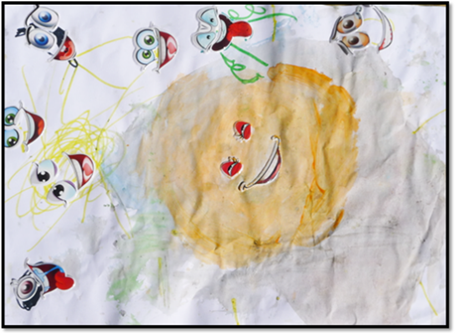

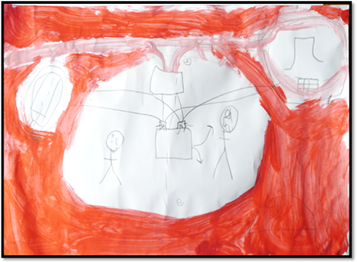

The idea for this research project developed when two of my (first author’s) son’s friends died in 2014. This was his first experience with death, and having severe Autism, he found this difficult to understand. Numerous visits to a psychiatrist and psychologist did not appear to help because he needed a way to express his grief and sadness without relying on verbal means to communicate. So we began drawing about his feelings (Artwork 1 and Artwork 2) together as a way of healing. He also expressed this grief in his “Minecraft”TM world (Artwork 3).

Artwork 1. Missing my friends (Ryan).

Artwork 2. Em in heaven (Ryan).

Artwork 3. In the virtual world of Minecraft™, visiting Ebony and Emily in heaven with a ladder structure that allowed him to return home when he is ready (Son of the first named author).

2. Literature

The American Psychiatric Association [APA] describes Autism as a neurological disorder, characterised by impairments in social interactions, communication and restricted, repetitive behaviour, interests and activities. Autism also affects a person’s sensory processing capabilities, their cognitive functioning and emotional regulation [2]. The Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.) identifies 3 levels of Autism ranging from level1 requiring the lowest level of support to level 3 requiring the most support [2]. Without support from family and teachers, individuals at Level 1 will have noticeable impairments in social communication and expressing emotions, and could experience difficulties in initiating or maintaining social interactions and understanding social cues [2]. The implications for their educational experiences means they may feel isolated from their peers, confused and overwhelmed by what expressions are expected and in turn, may be vulnerable to depression [3].

Individuals at Level 2 have marked deficits in social communication, including verbal and non-verbal skills. Even with supports in place, these individuals typically struggle with normal back and forth conversations; have limited sharing of interests and emotions, limited initiation of social interaction and poor social imitation [2]. The consequence to this may result in the child communicating their frustrations through inappropriate behaviours such as outbursts or tantrums [4].

Individuals at Level 3 have severe deficits in social communication and in expressing emotions which impact on all aspects of their functioning. These individuals seldom initiate social interaction and have very poor social imitation skills [2]. The implications for their education means they may never develop words to describe how they are feeling [5]. The consequence of this may lead to frustration, aggression or self-injury [6].

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has concluded that there was a 79% increase of people with Autism from 2009 to 2012; equating to a diagnosis of Autism for one in every 100 Australians [7]. Autism is a lifelong disability with no known cause. Studies have indicated that early intervention will improve the outcome and quality of life for individuals on the Autism spectrum [8] [9] [10] [11]. Today there are an abundance of empirically supported interventions in use for ASD including those used to assist the development of communication skills in individuals on the Autism spectrum, and Art therapy, although not a well-established intervention, is one of these.

Art therapy can be described as using the creative process to explore inner feelings, foster self-awareness, manage behaviours and reduce anxiety [12]. The main purpose of Art therapy is to enable individuals to express what they cannot say verbally through paintings, drawings, or other Art forms [13]. Research has indicated that Art therapy can be effective for children on the Autism spectrum as it can be tailored to the individual’s preference for visual information, difficulties with verbal communication, behaviour and sensory sensitivities but can also develop positive relationships [5]. Art therapy is particularly useful for individuals with Autism because it is a form of self-expression that requires little or no verbal interaction [14].

Even though the application of Art therapy for individuals with ASD is not new, there is very little research in this area, however [15] has acknowledged a small but steady increase of research in this field. [5] aimed to use “pre-representational drawing activities…as a foundation for the development of communication skills” (p. 101). [16] sought to develop communication skills through co-constructive experiences of positive relationships and social interaction by reintroducing spontaneity and improvisation in shared Art making sessions. They found the subjective role of the therapist added an interactive element to the Art making sessions, referring to this as the “Interactive Square” model. This model is an approach to art therapy that “shifts the therapist role from spectator or observer to an active participant” [16] within an art-making session. It was our intention that this research project specify and study only the area of communicating emotions and feelings by adapting and developing Bragge and Fenner’s co-creative approach with Evans and Dubowski’s [5] foundational model for developing communication skills for children with Autism.

3. Methods

The intention of this research was to tell in-depth stories of the lives of two children living with Autism and how Art making impacted on their communication of feelings and emotions. In line with this aim and the observation of [17] that Art therapy research typically uses qualitative methods, a case study design was employed. [18] writes that case study is applicable when a study requires a “close examination of people” (p. 218) gathered from multiple perspectives. The results are presented in a narrative form, telling a story by interpreting the children’s educational experiences, and incorporating first-person accounts with reference to the images created. All participants in this research have been provided with pseudonyms in order to protect their identity.

Approval to conduct the research was granted by the Tasmanian Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (SSHREC). Consent for participation was given by the child when they had the capacity to make that decision, and also from the parents or guardians on their child’s behalf. For the duration of the project, ongoing communication with the parents was facilitated to ensure the voluntary nature of their child’s participation and to ensure they were comfortable with the process. Parents were given the option of attending the Art making sessions.

This research used purposive sampling [19] [20] [21] to recruit the two child participants. To be eligible, participants needed to:

1) Have had a formal diagnosis of ASD prior to the study;

2) Be aged between six and twelve years old inclusive (Prep to Year six);

3) Be attending a Tasmanian primary school (South);

4) Have demonstrated a willingness to be involved in Art making (i.e. no strong sensory aversion to Art materials/colours/smells etc.) regardless of their technical ability; and

5) Have the physical capacity (i.e. sight, motor coordination in hands) necessary to engage in Art making.

Two boys, Ryan and James, participated in this study. At the time of this study, Ryan was a seven-year-old boy with Level 1 ASD living with his father, mother and older brother. The mother was a part-time lecturer at the University. Ryan attended an all-boys, independent school situated in a high socio-economic area, and was in a Prep class part-time with a teacher aide (Ms. A). James was a 10-year-old boy living with his mother and younger brother. His mother worked as a volunteer for a Christian social welfare organisation and cared for her children full-time, and his father had frequent access to both boys. James was described by his mother as having Level 2 ASD, mild Cerebral Palsy, motor dyspraxia and a Chromosome Abnormality. At the time of this study James attended various interventions and therapies including speech therapy, occupational therapy, physiotherapy and a psychologist. James was able to adequately communicate his feelings through verbal means but either “kept his emotions bottled up or would clam up” (James’ Mother).

Throughout October 2015, the first author attended the participants’ classrooms as a “helper” to establish a rapport with them. These sessions were approximately one hour in duration, twice a week for two weeks and were not Art therapy related. In November the first author began fieldwork, commencing Art making sessions and collecting data. There were a total of eleven Art making sessions (five with Ryan and six with James), and for some of these sessions co-creation of Art took place with the participant and the first author and sometimes with the Teacher’s Aide. This co-creative approach was based on Bragge and Fenner’s model of the “Interactive Square” [16].

4. The Art Making Experiences

As discussed earlier it is not possible to present all data from the two participants, and indeed to summarise data would over-simplify the complexity and individuality of each Art making experience. Thus the two most powerful and creatively linked sessions from Ryan are presented here?his second and third Art making sessions, and three linked and powerful sessions from James are presented?his third, fourth and fifth, all in edited and reduced format.

4.1. Ryan

Before the session, Ms. A had informed me that Ryan had had another “up and down” morning. They had just finished rehearsals for the end of year Christmas performance. Apparently the noise and excitement had “wired” Ryan up and he was finding it difficult to sit and concentrate. Ryan was eager to get started, and I decided to use visual prompts in this session in order to enable his communication (Figure 1).

“What’s dis?” he asked as he pointed to the emotions wheel. “It’s a wheel with pictures of feelings on it so that you can show me how you feel when you look at these pictures here.” I showed him a visual prompt of a boy holding his hands to his ears (Figure 2), I explained that his ears were hurting from loud noises. I then asked how loud noises made Ryan feel. He turned the wheel to sad. He picked up the black marker and drew himself in the centre and noises that distress him (Artwork 4). On the right hand side was a megaphone and above his head was a gun (in reference to the athletics carnival he had participated in the week before). He drew sunglasses over his eyes with tears dripping down his face. He assured me that his mouth was not smiling but clenching from the noises.

![]()

Figure 1. Visual prompt: Emotions wheel.

![]()

Figure 2. Visual prompt: Loud noise response.

Artwork 4. Feeling sad from loud noises (Ryan).

The next visual prompt picture I showed Ryan was a crowded environment (Figure 3).

Ms. A commented on the picture and said it looked a lot like the recent school fun fair. He immediately picked up the emotions wheel and turned to the happy face as well as the sad face. As he was drawing the jumping castle he proclaimed that he liked rides but did not like the crowds (Artwork 5).

![]()

Figure 3. Visual prompt: Crowded environment.

Artwork 5. Feeling happy and sad in a crowded environment (Ryan).

Ryan saw the visual prompt picture of a boy playing with toys (Figure 4). “Dhat (that) one” he said pointing to the picture.

“How does it make you feel to play with your toys Ryan?” I asked. “Happy!” He began drawing a small figure in the centre. “Dhat’s me!” His face had a large smile and the eyes were looking up at his toy which was twice the size of him. “Who is that?” I asked. “Optimus Prime” (a Transformer toy) he said as he jumped out of his seat. Optimus Prime was his current favourite toy and playing with him made him happy (Artwork 6).

The last visual prompt I showed Ryan was a boy with someone inside a thought bubble to represent missing a person (Figure 5). I was aware that Ryan’s mother was currently overseas at a conference.

“Mummy! I miss mummy!” he yelled. “Can you show me how you feel when you miss mummy?” I queried. Ryan leaned his head onto his left arm and began to draw himself on the right-hand side of the picture (Artwork 7).

He found the sticker eyes that best represented sad and stuck them down on to his face. He did the same for his brother (far left-hand side). The figure in the middle is his father and has one of his arms on his brother’s shoulder appearing

![]()

Figure 4. Visual prompt: Playing with toys.

![]()

Figure 5. Visual prompt: A missing person.

Artwork 6. Feeling happy playing with optimus prime (Ryan).

Artwork 7. Missing mum and feeling sad (Ryan).

happy. Likewise with the dog in the bottom right-hand corner. “You and your brother miss mummy, Ryan?” “Yes” he whispered.

In the following session Ryan requested to paint on an A2 piece of paper. He stood up out of his chair and organised the paint pots in a row. With intense concentration he began to paint large circles with orange. “This is dad happy because mum is home” he said as he placed the stickers in the middle of the paper (Artwork 8). He continued to add more people. “Who are all these people Ryan?” I asked. “This is mum (top right), this is me (top left), this is my brother (bottom left) and the rest are my grandads and grandmas” he replied.

As he was applying the finishing touches to his painting, Ryan took a step back, had a look at the picture he created and said “My family is happy”.

4.2. James

As we were walking over to the Art room, I asked James how his morning had been. He sighed and said “Well, not so good and I was really angry at one point. I was playing Octopus (a ball game) with the class and I always get targeted by Gavin (pseudonym) because I’m slow. I immediately felt angry but I didn’t want to get into a fight so I told Mr S”. I asked James whether he could “shake off” the comments Gavin made. To which he replied, “No, not at all and I will go to bed thinking about it tonight which is why I like Tuesdays and Fridays because I get to do painting with you and it makes me feel better.” James wanted to start with a self-portrait of being angry. He picked up the smallest brush in the pile and chose to paint the plaster face red, James’ angry colour (Artwork 9). With tiny strokes, he began to cover the face. Although he was still talking to me about the incident, he sat very still.

Artwork 8. The whole family is happy because mum is back (Ryan).

Artwork 9. Being the target and feeling angry (James).

For the next activity, James began by sketching out an intricate map of an imaginary city with lead pencil (Artwork 10). He stated that because the world was overpopulated he would like to escape and go to the moon and stay there. The map included a rocket landing pad, an underground metro system, a railway that connected with the metro, an industrial and residential area, a theme park and the town centre for everyone to gather.

While painting with the largest brush he could find, James would stand up and pace while he was thinking of his ideas. In order to communicate the structure of his ideas, he chose to talk to me using his peripheral vision or he was unable to focus. As the drawing of the town emerged, he discussed complex issues surrounding the rich and poor. “This is the industrial area” he said as he pointed to the orange area on the right hand side “which is why I am putting the poor people here because rich people don’t like smoke and dirt. The poor people won’t have any train connections either because they don’t have any money anyway, so they can just walk everywhere. Rich people like to be entertained, so I will put a theme park near the rich residential area” (the gold glitter area on the lower left hand side). “Why do you think these people are poor, James?” I asked as I pointed to the orange area. “Because they used all of their savings to try to get here (to the moon) and now they have nothing” he replied. He continued the conversation with reference to refugees and the former Australian Prime Minister, Tony Abbott’s policy in this area, the refugees in Syria and Islamic State.

“So James, how are you feeling today?” I asked at the start of the next session. “Great because I didn’t have PE, so I haven’t been a target today” he replied. He looked up and his eyes appeared to have dark circles. “Are you feeling tired James?” I asked. “Yes, I have been up all night ‘You Tubing’ and didn’t go to sleep until 1am. My Melatonin wasn’t working”.

Artwork 10. Getting out of here and going to the moon! (James).

James expressed an interest in continuing with the same theme from the last Art session. However, this time, instead of painting humans colonising the moon, it was robot scientists invading the dwarf planet “Sedna”. He began sketching out the town plan in lead pencil (Artwork 11). James was sitting still, apart from the occasional movement of biting his tongue when concentrating. Although he was calm, his eyes were darting back and forth. As he was talking to me, he was fiddling with the buttons on his shirt. There appeared to be too much information that he needed to get out. He began to speak about what would happen if chaos broke out on Sedna. Apparently, if this red dwarf planet had problems with bully robots, their microchips would be removed and they would be re-programmed until they “were nice to others”.

For part of the next session, one of my goals was for me to co-create with James and to enable him to express his feelings about being bullied in PE. I asked James if he thought it was a good idea if we painted a picture together (Artwork 12). He agreed and shuffled his chair closer. “Do you remember the other day James, when you told me about how you felt you were being targeted in P.E?” I said. “Let’s draw what happened that day, and think of what you could do next time it happens” I continued. I began sketching people in the far left-hand side of the picture. James leaned over and drew faces on two of them. “There are always two that target me” he said as he drew aggressive faces on them. He continued to paint his face in blue Texta, James’ sad colour. I noticed him sitting on the edge of the seat as though he was trying to remove himself from the situation. So I decided to change tactics. “What could you do to make yourself feel better?” I asked. “Tell Mr S” he replied. I began sketching his teacher when he reminded me that he wore glasses and did not have much hair. “Like this?” I sought approval for a Mr S look-a-like. James laughed hysterically. “Yes, exactly like that” he said as he moved closer to the table. “I’ll draw myself down here talking to him, ok?” he said. James informed me that after telling Mr S, he felt angry and then sick (the red and green circles).

Artwork 11. The year 2205: 90377 Sedna will be colonised [half complete] (James).

Artwork 12. Ways to feel better (James, co-construction with first author).

“So how can you get back to being happy?” I asked James. James proceeded to make a “happy list” on the far right-hand side of the page. After he wrote “leaving the room”, it triggered a memory from the other week when his class had a relief teacher. “All I wanted to do was run out of the room because everyone was so loud” he said. He then continued in great depth about his three levels of noise tolerance. “I was definitely at level three this day. That’s when I can’t cope and my brain literally shuts down. I can’t talk, I can’t think, I can’t tell anyone how I feel”. “Wow James” I said, acknowledging his pain. “Why can’t you wear headphones in that instance?” I asked. “I’m not allowed to” he said as he stared into space. He slumped in his chair again. He said he was thinking about the two boys that target him again.

“Would you like to paint what they look like?” I asked. James began with drawing a large circle in the centre with black Texta (Artwork 13). His teeth were tightly clenched onto his tongue. James had morphed two people into, what looked like, one monster. “How are you feeling James?” I asked quietly. “Sad, because I know they will always target me” he replied. I could sense his unhappiness by how quiet he was. I remembered reading an Art strategy which could help victims of bullying gain a sense of control over their situation and relieve anxieties. So I suggested drawing toxic slime spewing of or their mouth/s. He half laughed.

Artwork 13. The Bullies (James, co-construction with first author).

Suddenly James’s face changed. He was becoming uncomfortable. “Why don’t you finish your Sedna painting?” I suggested. James immediately shot up in his chair and started talking about Space again. As he was drawing the “portal colours” (orange and blue) his mind was escaping to planet Sedna (Artwork 14). I was relieved when his excessive talking returned. I informed the school about the bullying that the Art making had surfaced, they were already dealing with it.

5. Reflections and Discussion

Ryan and James’ Art making sessions contribute to the argument that the processes of Art making can be an effective intervention for children on the Autism spectrum as it can be tailored to the individual’s preference for visual information, difficulties with verbal communication, behaviour and sensory sensitivities but can also develop positive relationships [5]. Similar to previous research in this field, including [16], [5], [22], [1], and [23], we found that the Art making process was associated with improved speech, communication, and social interaction. Key themes which were not anticipated in this research included indications of: 1) increased self-esteem and general wellbeing; and 2) increased concentration, sensory regulation and flexibility to change. Also, both participants experienced the process in markedly different ways, including an increase in anxiety levels associated with the co-creating process for James.

The findings from this research study suggest that the Art making sessions were an enjoyable and beneficial experience for both Ryan and James. Given the diversity of personalities across the Autism spectrum, not surprisingly, the outcomes from this study were very different for the two participants. Drawing from the work of [15], it is possible that numerous factors may have contributed to these differences, such as their developmental ages, personal circumstances and levels of diagnoses.

Ryan was only six at the time of this study and although he had a Level 1 diagnosis of Autism, he also had Apraxia of speech. This communication disorder

![]()

Artwork 14. The Year 2205: 90377 [complete] (James).

affected his ability to produce words correctly when communicating. The Art making sessions provided the opportunity for him to practice his sounds while painting in a non-threatening environment. At the time of this study, Ryan’s mother was also away attending a conference overseas. In previous years when this occurred, his teacher’s aide stated that his mother’s absence would leave him “quiet and withdrawn”. However, through the Art making sessions, Ryan was able to express his sadness through his paintings but also paint ways that he could feel better.

In contrast to Ryan’s experience, James was pre-pubescent at the time of this study and his situation was far more complex with the social dynamics surrounding his peers at school. He was very much aware of his Autism and in particular his Cerebral Palsy. James identified his Cerebral Palsy in order to explain why he was bullied and admitted that he was unable to verbalise his feelings when he felt distressed. The Art making sessions provided the opportunity for James to escape the realities of his diagnosis and his bullies. This was evident in remarks he made about how well he was sleeping because he was able to “get it (his feelings) out”. Even though Ryan and James had verbal language, in times of distress they were unable to physically find the words to express their feelings [5] [13]. These Art making sessions provided both boys the opportunity to express what they could not say in words.

Although James did not explicitly state that he was depressed by being bullied, he constantly mentioned his sleep was affected by the negative thoughts and anxieties surrounding his tormentors. On several occasions James reported a positive attitude towards the way he felt about himself and that his sleeping improved as a result of the Art making sessions. This finding is similar to [23] literature review in which she stated the Art making process enhanced the lives of individuals with ASD by increasing their general-wellbeing.

Ryan and James were both identified as having sensory issues. This in turn affected their ability to sit still and concentrate. For Ryan, this meant swaying his head from side to side if he needed a break or was becoming agitated. He was also overly responsive to loud, deep sounds. James was overly responsive to certain objects and sounds and would pace back and forth if he felt overwhelmed. As the Art making sessions progressed through the weeks, both participants showed an increase in concentration and as such, a reduction of the stereo- typical behaviours of pacing or swaying. This was similar to [24] case study and [23] literature review, the findings of which indicated positive behaviours associated with sensory difficulties during and after Art making sessions.

For Ryan, the Art making process stimulated changes of behaviour, similar to those reported by [1] in their clinical case study reviews into Art therapy with children with ASD. The creative process increased his flexibility to quickly alternate between activities. Ryan verbalised to Ms. A and the first author that he found the co-creating process exciting. Furthermore, [16] found this approach increased language and confidence, as well as facilitated the use of humour. Perhaps the focus on positive formative experiences and being together with family provided an ideal reference point for a co-creating Art making process.

Unfortunately for James, the co-creative process proved to be too intrusive and impeded the Art making process. In contrast to [16]’s research, working alongside James in a co-creative way increased his anxiety levels. Whilst creating the bully paintings together with the first author he became quiet and withdrawn. Sensing this anxiety, I immediately ceased co-creating and offered him the choice of returning to his “escape painting”. James’ response to co-creation was probably explained by the emotional impact of the topic being explored: the recent experiences of bullying. It seemed that creating artworks by himself whilst simultaneously talking to me proved to be more beneficial for James and during this creating, only seemed to need an empathic presence from me. The unexpected increase in anxiety levels for James whilst co-creating demonstrates that caution must be taken with practices surrounding children with Autism (and indeed neuro-typical children) and complex cases such as bullying.

The Art making process provided an alternative outlet for self-expression at school. This process may reduce the challenges individuals with Autism face, therefore improving the quality of life for them as well as their families and teachers. The main issue that this study addressed was the communication difficulty children with ASD endure at school and at home. The diversity of the Autism spectrum means no two individuals are alike, and unsurprisingly the outcomes from this study were very different for the two participants. Reflections on the Art making process in this study did, however, lend support to the idea that the processes of Art making can easily be diversified to suit individuals with Autism, regardless of their level of diagnosis. This means the inclusion of an Art making program could be implemented in schools by social workers, Art therapists or school psychologists to reduce behavioural issues associated with communication difficulties for children with Autism. Furthermore, the Gunawirra program (2016), in rural New South Wales, state it is possible that a specific Art making program in a pre-school or school setting could also meet the increasing needs of other children who require more assistance than the classroom teacher can reasonably be expected provide; for example, with children who are emotionally disturbed, suffer from trauma, mental health or are exposed to abuse or domestic violence. But there may also be opportunities for classroom teachers to embed similar Art making for all their students, such as when designing activities to develop students’ “Personal and Social Capabilities” [25], for which identifying, communicating, and managing emotions is central.

Communication and self-expression are a fundamental part of how we exist and interact with the world around us [26]. Ryan and James were given the opportunity to express their emotions to others about what makes them happy and sad. If an individual was unable to communicate their feelings and emotions, a change in behaviour may escalate until a teacher or a parent does take notice.

The social interaction between the two individual participants and myself increased as the Art making sessions progressed. Creating artwork in a non-threatening environment allowed both boys to relax and remain calm and in turn offered me a glimpse into their unique personalities. Parents with children on the Autism spectrum often feel that they cannot connect or interact meaningfully with their child [27]. Making Art together can provide parents the opportunity to improve back and forth interactions with their child and increase the child’s desire to want to communicate socially.

This Art making process was associated with improvements in Ryan’s and James’s sensory issues, concentration levels, and in their flexibility to change. This finding suggests that specific art-based activities could help teachers and teacher aides manage a student’s behaviour relating to sensory issues and in turn increase classroom concentration. The Art making process may also support the transitions between classroom activities by increasing their tolerance and flexibility to change; something that individuals with ASD generally find difficult [28].

There were several limitations identified for this research study. The most obvious limitation was the small number of participants involved. Ideally, a greater number of participants could have provided more insight into the experiences created by the Art making sessions. [29] stated a small sample size may not accurately reflect the experiences of the general population; however, the aim for this research study was not to produce results with quantifiable outcomes but rather to gather in-depth data pertaining to individual experiences. Recruiting sufficient participants also presented a challenge and disrupted this research study’s timetable significantly, thereby reducing the Art making sessions to five instead of six and making it necessary to cancel Ryan’s follow-up session.

Future research could include standardised measures of self-esteem, anxiety levels and stereo-typical behaviours and monitoring these changes over a substantial period of time. In her book, “Art therapy, research and evidenced-based practice”, [15] discusses quantitative methodologies that could generate evidence and increase confidence in Art therapy research.

Research with students in different age groups would provide additional information on this topic. Also, future research could include group Art making sessions in schools and how teachers could support their students on the Autism spectrum to communicate feelings and emotions through art. Similarly, further research into Art making and family group sessions could facilitate or enhance understanding, communication and emotional relatedness between all family members [30].