Abstract

We present a multi-wavelength photometric catalog in the COSMOS field as part of the observations by the Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey. The catalog is based on Hubble Space Telescope Wide Field Camera 3 (HST/WFC3) and Advanced Camera for Surveys observations of the COSMOS field (centered at R.A.:  , Decl.:

, Decl.: ). The final catalog has 38671 sources with photometric data in 42 bands from UV to the infrared (

). The final catalog has 38671 sources with photometric data in 42 bands from UV to the infrared ( ). This includes broadband photometry from HST, CFHT, Subaru, the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy, and Spitzer Space Telescope in the visible, near-infrared, and infrared bands along with intermediate- and narrowband photometry from Subaru and medium-band data from Mayall NEWFIRM. Source detection was conducted in the WFC3 F160W band (at 1.6 μm) and photometry is generated using the Template FITting algorithm. We further present a catalog of the physical properties of sources as identified in the HST F160W band and measured from the multi-band photometry by fitting the observed spectral energy distributions of sources against templates.

). This includes broadband photometry from HST, CFHT, Subaru, the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy, and Spitzer Space Telescope in the visible, near-infrared, and infrared bands along with intermediate- and narrowband photometry from Subaru and medium-band data from Mayall NEWFIRM. Source detection was conducted in the WFC3 F160W band (at 1.6 μm) and photometry is generated using the Template FITting algorithm. We further present a catalog of the physical properties of sources as identified in the HST F160W band and measured from the multi-band photometry by fitting the observed spectral energy distributions of sources against templates.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

1. Introduction

The Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey (CANDELS: PI. S. Faber and H. Ferguson; see Grogin et al. 2011 and Koekemoer et al. 2011) is the largest Multi-Cycle Treasury program ever approved on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), with more than 900 orbits, and it was designed to use deep observations by the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) and Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) instruments to study galaxy formation and evolution throughout cosmic time in five fields in many different bands. The observations were done by the HST/WFC3 as the main mode with ACS observations in parallel. The CANDELS images are publicly available, and multi-wavelength photometric catalogs are made available by the CANDELS team following the release of the images. All CANDELS photometric catalogs were selected based on the WFC3 F160W band and this is the reference image for all the other HST and non-HST data. This provides a data set with consistent photometry and physical properties across all the fields targeted as part of the survey. The CANDELS catalogs for the first two observed fields of UDS and GOODS-S (Galametz et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013) are already publicly available31 and the three fields of COSMOS (this work), EGS (M. Stefanon et al. 2017, in preparation), and GOODS-N (G. Barro et al. 2017, in preparation) are in progress. The CANDELS observations are aimed at achieving several major science goals that could only be attained with data at the depth and resolution of CANDELS. These include studying the most distant objects in the universe at the epoch of reionization in the cosmic dawn (e.g., Finkelstein et al. 2012a; Grazian et al. 2012; Yan et al. 2012; Lorenzoni et al. 2013; Oesch et al. 2013; Duncan et al. 2014; Bouwens et al. 2015; Caputi et al. 2015; Finkelstein et al. 2015; Giallongo et al. 2015; Mitchell-Wynne et al. 2015; Roberts-Borsani et al. 2016; Song et al. 2016), understanding galaxy formation and evolution during the peak epoch of star formation in the cosmic high noon (e.g., Bell et al. 2012; Bruce et al. 2012; Kocevski et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2013; Wuyts et al. 2013; Barro et al. 2014; Hemmati et al. 2014, 2015; Whitaker et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2015), and studying star formation from deep UV observations and cosmological studies from supernova observations (e.g., Jones et al. 2013; Teplitz et al. 2013; Rodney et al. 2014, 2016; Strolger et al. 2015). These main science goals are described in more detail by Grogin et al. (2011) and Koekemoer et al. (2011).

One of the major goals of modern observational cosmology is to study the formation and evolution of galaxies with cosmic time. Recent advances in this frontier have been enabled by the availability of observations in different wavelengths, targeting different populations of galaxies (e.g., York et al. 2000; Wolf et al. 2003; Bell et al. 2004; Giavalisco et al. 2004; Skrutskie et al. 2006; Faber et al. 2007; Lawrence et al. 2007; Scoville et al. 2007b; Ilbert et al. 2013; Khostovan et al. 2015; Shivaei et al. 2015; Hemmati et al. 2017; Vasei et al. 2016). The advent of HST benefited many such studies by making it possible to have the deepest observations of the sky in multiple bands. In particular the installation of the WFC3 on board HST initiated a new stage for studying galaxy evolution at new extremes (McLeod et al. 2015; Oesch et al. 2016).

Galaxy populations at different look-back times range from very blue star-forming galaxies to red dusty or very old systems. Understanding the evolution of these populations relies on the availability of multi-wavelength photometric data from the bluest to the reddest bands possible. The CANDELS multi-wavelength catalogs combine the best and deepest observations by HST with the deepest ground-based observations and Spitzer Space Telescope data (Galametz et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013). These catalogs of tens of thousands of extragalactic sources, consistently measured across many bands from  , bring a unique opportunity to study galaxy evolution.

, bring a unique opportunity to study galaxy evolution.

The Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS; Scoville et al. 2007b) centered at R.A.:  , Decl.:

, Decl.:  ) is a 2 deg2 field located near the celestial equator. It was initially picked to maximize the visibility from observatories from both hemispheres and was specifically chosen to avoid any bright X-ray, UV, or radio sources (Scoville et al. 2007b) and to be large enough for studies of large-scale structure (e.g., Scoville et al. 2007a, 2013; Kovač et al. 2010; Darvish et al. 2014, 2015b).

) is a 2 deg2 field located near the celestial equator. It was initially picked to maximize the visibility from observatories from both hemispheres and was specifically chosen to avoid any bright X-ray, UV, or radio sources (Scoville et al. 2007b) and to be large enough for studies of large-scale structure (e.g., Scoville et al. 2007a, 2013; Kovač et al. 2010; Darvish et al. 2014, 2015b).

The COSMOS field was targeted by CANDELS in a north–south strip, lying within the central ultra-deep strip of the UltraVISTA imaging (McCracken et al. 2012) and hence also the Spitzer SEDS imaging (Ashby et al. 2013) in order to ensure the best possible supporting data at longer near-infrared wavelengths. The HST observations cover an area of  arcmin2 in the WFC3/IR with parallel ACS observations. The catalog was selected in the HST/WFC3 F160W band and has multi-band data for 38671 objects from ∼0.3 to 8 μm. These fluxes are measured consistently across all these bands and in agreement with photometry measurement techniques adopted by all CANDELS catalogs. We use the unprecedented depth and resolution provided by the HST for measuring the flux of the faintest targets across all bands. By fitting this multi-waveband information with template libraries, we also measured photometric redshift and stellar mass for each object.

arcmin2 in the WFC3/IR with parallel ACS observations. The catalog was selected in the HST/WFC3 F160W band and has multi-band data for 38671 objects from ∼0.3 to 8 μm. These fluxes are measured consistently across all these bands and in agreement with photometry measurement techniques adopted by all CANDELS catalogs. We use the unprecedented depth and resolution provided by the HST for measuring the flux of the faintest targets across all bands. By fitting this multi-waveband information with template libraries, we also measured photometric redshift and stellar mass for each object.

The paper is organized as follow. Section 2 presents the data used to compile the catalog. Section 3 describes our photometry of the HST, Spitzer, and ground-based bands. Section 4 is devoted to data quality checks for our TFIT photometry. Physical parameter estimation using the measured photometry is presented in Section 5. In Section 6 we investigate the applications of our deep photometry on studies of high-redshift star-forming and quiescent galaxies. We summarize our results in Section 7. Throughout this paper we assume a cosmological model with  ,

,  , and

, and  . All magnitudes are in the AB system where

. All magnitudes are in the AB system where  (Oke & Gunn 1983).

(Oke & Gunn 1983).

The CANDELS COSMOS photometry catalog will be publicly available through the CANDELS Web site32 along with the physical properties estimates and all the documentations. These will also be available on the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST),33 via the online version of the catalog and through Centre de Donnees astronomiques de Strasbourg (CDS). We will also make these data available through the Rainbow Database34 (Pérez-González et al. 2008; Barro et al. 2011).

2. Data

The COSMOS field (Scoville et al. 2007b) has been observed in many different wavelengths from the X-ray to the far-infrared. There are observations from the CFHT/MegaPrime in the u*, g*, r*, i*, and z* (Gwyn 2012), from the Subaru/Suprime-Cam in the B,  , V,

, V,  ,

,  , and

, and  (Taniguchi et al. 2007), from the VLT/Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) in the Y, J, H, and Ks bands (McCracken et al. 2012), from Spitzer in the four IRAC bands (Sanders et al. 2007; Ashby et al. 2013), VLA (Schinnerer et al. 2007), XMM (Cappelluti et al. 2007; Hasinger et al. 2007), Chandra (Elvis et al. 2009; Civano et al. 2016), and GALEX (Schiminovich et al. 2005). There are also numerous medium- and narrowband observations available in the COSMOS from Mayall NEWFIRM (Whitaker et al. 2011) and Subaru Suprime-Cam (Taniguchi et al. 2015). The full COSMOS field has been observed with HST in F814W (Koekemoer et al. 2007) and contains more than 2 million galaxies with multi-band data from the UV to the far-IR (Capak et al. 2007; Mobasher et al. 2007; Ilbert et al. 2009, 2013). Furthermore, COSMOS has been followed up spectroscopically by the larger and most sensitive telescopes/instruments like VLT/VIMOS (e.g., Lilly et al. 2009; Le Fèvre et al. 2015) and Keck/DEIMOS and MOSFIRE among others.35

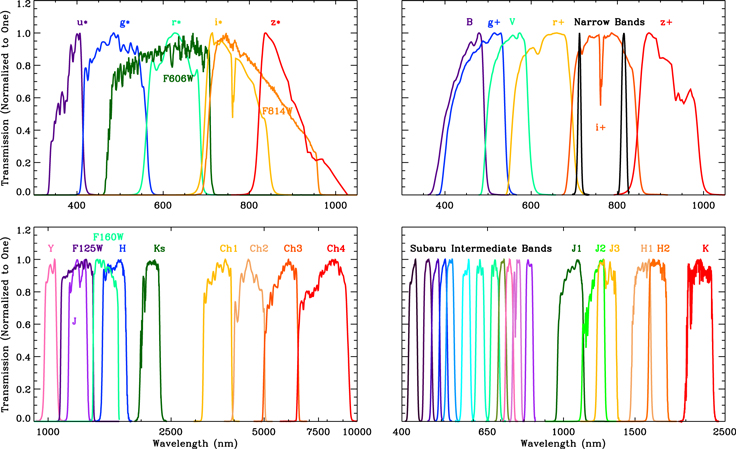

This makes it possible to study different populations of galaxies from blue and young systems at shorter wavelengths to red dusty or old objects at longer wavelengths. These ancillary data are accompanied by high-resolution observations from CANDELS using the HST in both visible and near-infrared. Figure 1 shows the transmission curves for all bands included in the CANDELS COSMOS catalog.

(Taniguchi et al. 2007), from the VLT/Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) in the Y, J, H, and Ks bands (McCracken et al. 2012), from Spitzer in the four IRAC bands (Sanders et al. 2007; Ashby et al. 2013), VLA (Schinnerer et al. 2007), XMM (Cappelluti et al. 2007; Hasinger et al. 2007), Chandra (Elvis et al. 2009; Civano et al. 2016), and GALEX (Schiminovich et al. 2005). There are also numerous medium- and narrowband observations available in the COSMOS from Mayall NEWFIRM (Whitaker et al. 2011) and Subaru Suprime-Cam (Taniguchi et al. 2015). The full COSMOS field has been observed with HST in F814W (Koekemoer et al. 2007) and contains more than 2 million galaxies with multi-band data from the UV to the far-IR (Capak et al. 2007; Mobasher et al. 2007; Ilbert et al. 2009, 2013). Furthermore, COSMOS has been followed up spectroscopically by the larger and most sensitive telescopes/instruments like VLT/VIMOS (e.g., Lilly et al. 2009; Le Fèvre et al. 2015) and Keck/DEIMOS and MOSFIRE among others.35

This makes it possible to study different populations of galaxies from blue and young systems at shorter wavelengths to red dusty or old objects at longer wavelengths. These ancillary data are accompanied by high-resolution observations from CANDELS using the HST in both visible and near-infrared. Figure 1 shows the transmission curves for all bands included in the CANDELS COSMOS catalog.

Figure 1. Transmission curves for the CFHT and ACS visible (top left), Subaru optical broadband and narrowband (top right), WFC3 and UltraVISTA near-infrared and Spitzer infrared (bottom left) and the Subaru intermediate- and NEWFIRM medium-band filters (bottom right) used in the COSMOS CANDELS TFIT catalog. These cover observations at ∼0.3–8 μm in 42 filters. The filters are adopted from http://cosmos.astro.caltech.edu/page/filterset. The effective wavelength of the filters are reported in Tables 1 and 2.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image2.1. CANDELS HST Observations

The CANDELS COSMOS field was observed by the WFC3 in F125W and F160W (J125 and H160) and in parallel by the ACS in the F606W and F814W filters (V606 and i814). The WFC3 observations covered a rectangular grid of 4 × 11 tiles ( ) running north to south, allowing for maximum contiguous coverage in the near-infrared. The field was observed over two epochs with each tile observed for one orbit in each epoch. The one-orbit observations were divided into two exposures in F125W (

) running north to south, allowing for maximum contiguous coverage in the near-infrared. The field was observed over two epochs with each tile observed for one orbit in each epoch. The one-orbit observations were divided into two exposures in F125W ( orbit depth) and F160W (

orbit depth) and F160W ( orbit depth) along with parallel ACS observations in the F606W and F814W (Grogin et al. 2011; Koekemoer et al. 2011). The exposures in each orbit were dithered using a small-scale pattern providing half-pixel subsampling of the PSF and also ensuring that the hot pixels and persistences were moved around. The output is a calibrated and astrometry-corrected mosaics of all the exposures in the four individual HST bands. The astrometry is based on the CFHT/MegaCam i* imaging supplemented by deep Subaru/Suprime-Cam

orbit depth) along with parallel ACS observations in the F606W and F814W (Grogin et al. 2011; Koekemoer et al. 2011). The exposures in each orbit were dithered using a small-scale pattern providing half-pixel subsampling of the PSF and also ensuring that the hot pixels and persistences were moved around. The output is a calibrated and astrometry-corrected mosaics of all the exposures in the four individual HST bands. The astrometry is based on the CFHT/MegaCam i* imaging supplemented by deep Subaru/Suprime-Cam  imaging with absolute astrometry registered to the VLA 20 cm survey of the COSMOS field (Schinnerer et al. 2007; see also Koekemoer et al. 2007). This is also the adopted reference grid by the COSMOS team (Capak et al. 2007). All the ground-based and Spitzer data (described in the next Section) were aligned to the HST data astrometry using SWARP. For the present work we used the V0.5 release of the HST/ACS and WFC3 data available from the CANDELS website.36

The observation depth, effective wavelength, and the PSF information for each of the HST filters are summarized in Table 1.

imaging with absolute astrometry registered to the VLA 20 cm survey of the COSMOS field (Schinnerer et al. 2007; see also Koekemoer et al. 2007). This is also the adopted reference grid by the COSMOS team (Capak et al. 2007). All the ground-based and Spitzer data (described in the next Section) were aligned to the HST data astrometry using SWARP. For the present work we used the V0.5 release of the HST/ACS and WFC3 data available from the CANDELS website.36

The observation depth, effective wavelength, and the PSF information for each of the HST filters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the CANDELS COSMOS Broadband Data

| Instrument | Filtera | Effective | PSF | 5σ limiting depthc | Version | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelengthb | FWHM | |||||

| (Å) | (arcsec) | (AB Magnitude) | ||||

| CFHT/MegaPrime | ua | 3817 | 0.93 | 27.31 | July 2009 | Gwyn (2012) |

| ga | 4860 | 1.08 | 27.69 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| ra | 6220 | 0.84 | 27.18 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| ia | 7606 | 0.85 | 27.23 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| za | 8816 | 0.84 | 26.18 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| Subaru/Suprime-Cam | B | 4448 | 0.95 | 27.98 | V2 | Taniguchi et al. (2007) |

|

4761 | 1.58 | 26.78 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| V | 5470 | 1.33 | 26.86 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

|

6276 | 1.05 | 27.18 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

|

7671 | 0.95 | 26.95 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

|

9096 | 1.15 | 25.55 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| HST/ACS | F606W | 5919 | 0.10 | 28.34 | V0.5 | Koekemoer et al. (2011) |

| F814W | 8060 | 0.10 | 27.72 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| HST/WFC3 | F125W | 12486 | 0.14 | 27.72 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| F160W | 15369 | 0.17 | 27.56 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| VISTA/VIRCAM | Y | 10210 | 1.17 | 25.47 | DR1 | McCracken et al. (2012) |

| J | 12524 | 1.07 | 25.26 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| H | 16431 | 1.00 | 24.87 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| Ks | 21521 | 0.98 | 24.83 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| Spitzer/IRAC | 3.6 μm | 35569 | 1.80 | 24.41 | V1.2 | Ashby et al. (2013) |

| 4.5 μm | 45020 | 1.86 | 24.40 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| 5.8 μm | 57450 | 2.13 | 21.28 | V2 | Sanders et al. (2007) | |

| 8.0 μm | 79158 | 2.29 | 21.20 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

Notes.

aFilters adopted from http://cosmos.astro.caltech.edu/page/filterset. bCalculated as with

with  the filter response function (Tokunaga & Vacca 2005).

cThe 5σ limiting magnitude calculated within a circular aperture with a radius

the filter response function (Tokunaga & Vacca 2005).

cThe 5σ limiting magnitude calculated within a circular aperture with a radius  of the PSF in each filter.

of the PSF in each filter.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

2.2. Ground-based Observations

The full COSMOS field was targeted by the Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) 3.6 m telescope MegaPrime instrument in the u*, g*, r*, i*, and z* optical bands as part of the CFHT Legacy Survey37 with COSMOS being in the second Deep field. The MegaCam/MegaPrime camera used for the observations has a pixel scale of 0.187 arcsec pixel−1 (Boulade et al. 2003). The final images are from MegaPipe38 (Gwyn 2008) with zero-point adjustments. The image processing and stacking of the data is further described by Gwyn (2012). In this work we used the CFHTLS D2 mosaics 2009.39

The COSMOS field was also observed by the Subaru/Suprime-Cam in the B,  , V,

, V,  ,

,  and

and  broadband filters. The Suprime-Cam has a field of view of

broadband filters. The Suprime-Cam has a field of view of  with a pixel scale of 0.202 arcsec pixel−1. The data were processed using the IMCAT package.40

The individual frames were combined, flat-fielded, and photometry and astrometry calibrated. We refer the reader to Capak et al. (2007) and Taniguchi et al. (2007, 2015) for further description of the observations and data processing. There is also further observations of the COSMOS field by Subaru/Suprime-Cam in twelve intermediate bands along with narrowband data across two filters (Capak et al. 2007; Taniguchi et al. 2007, 2015) covering the wavelength range of

with a pixel scale of 0.202 arcsec pixel−1. The data were processed using the IMCAT package.40

The individual frames were combined, flat-fielded, and photometry and astrometry calibrated. We refer the reader to Capak et al. (2007) and Taniguchi et al. (2007, 2015) for further description of the observations and data processing. There is also further observations of the COSMOS field by Subaru/Suprime-Cam in twelve intermediate bands along with narrowband data across two filters (Capak et al. 2007; Taniguchi et al. 2007, 2015) covering the wavelength range of  . These observations were processed similarly to the broadband optical data discussed above (Taniguchi et al. 2015). Although slightly shallower than the optical broadband observations, these filters have higher resolving power than the former (with

. These observations were processed similarly to the broadband optical data discussed above (Taniguchi et al. 2015). Although slightly shallower than the optical broadband observations, these filters have higher resolving power than the former (with  Taniguchi et al. 2015), equivalent to low-resolution spectroscopy in the optical. The resolving power is even higher for the two narrowband filters (

Taniguchi et al. 2015), equivalent to low-resolution spectroscopy in the optical. The resolving power is even higher for the two narrowband filters ( Taniguchi et al. 2015) although with smaller wavelength coverage. This provides a unique data set for studying emission-line galaxies and high-redshift systems such as Lyα emitters (Shimasaku et al. 2006; Iwata et al. 2009; Koyama et al. 2014). Table 2 summarizes the Subaru intermediate and narrowband observations. We used the Subaru V2 mosaics for broadband and NB816 observations and V1 mosaics for intermediate and NB711 data available from the IRSA41

in this work.

Taniguchi et al. 2015) although with smaller wavelength coverage. This provides a unique data set for studying emission-line galaxies and high-redshift systems such as Lyα emitters (Shimasaku et al. 2006; Iwata et al. 2009; Koyama et al. 2014). Table 2 summarizes the Subaru intermediate and narrowband observations. We used the Subaru V2 mosaics for broadband and NB816 observations and V1 mosaics for intermediate and NB711 data available from the IRSA41

in this work.

Table 2. Summary of the CANDELS COSMOS Medium-band and Narrowband Data

| Instrument | Filter | Effective | PSF | 5σ Limiting Depth | Version | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength | FWHM | |||||

| (Å) | (arcsec) | (AB Magnitude) | ||||

| Subaru/Suprime-Cam | IA484 | 4849 | 1.14 | 26.34 | V1 | Taniguchi et al. (2007, 2015) |

| IA527 | 5261 | 1.60 | 26.04 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IA624 | 6232 | 1.05 | 26.21 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IA679 | 6780 | 1.58 | 25.65 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IA738 | 7361 | 1.08 | 25.94 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IA767 | 7684 | 1.65 | 25.33 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IB427 | 4263 | 1.64 | 25.91 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IB464 | 4635 | 1.89 | 25.66 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IB505 | 5062 | 1.44 | 25.82 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IB574 | 5764 | 1.71 | 25.66 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IB709 | 7073 | 1.58 | 25.79 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| IB827 | 8244 | 1.74 | 25.44 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| NB711 | 7120 | 0.79 | 25.56 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| NB816 | 8149 | 1.00 | 26.10 | V2 | ⋯ | |

| Mayall/NEWFIRM | J1 | 10460 | 1.19 | 24.60 | DR1 | Whitaker et al. (2011) |

| J2 | 11946 | 1.17 | 24.32 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| J3 | 12778 | 1.12 | 24.26 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| H1 | 15601 | 1.03 | 23.86 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| H2 | 17064 | 1.24 | 23.45 | ⋯ | ⋯ | |

| K | 21700 | 1.08 | 23.80 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

The ground-based near-infrared observations are from the VISTA (Emerson & Sutherland 2010) 4.1 m telescope VIRCAM large-format array camera (Dalton et al. 2006) in the Y, J, H, and Ks bands with mean pixel scale of 0.34 arcsec pixel−1. The complete contiguous  of UltraVISTA observations were done using a stripes pattern with

of UltraVISTA observations were done using a stripes pattern with  of the field observed with longer exposure (in four stripes) separating the observations into deep and ultra-deep regions (McCracken et al. 2012) with the CANDELS HST observations inside one of the ultra-deep stripes. The data were pre-processed at CASU,42

which includes dark subtraction, flat fielding, gain normalization, and initial sky subtraction (Irwin et al. 2004; McCracken et al. 2012). The data were further processed at TERAPIX using an iterative sky-background removal technique and resampled to a pixel scale of 0.15 arcsec pixel−1. McCracken et al. (2012) give more details on the data processing. We used the final DR1 mosaics of the UltraVISTA data for the CANDELS multi-wavelength catalog.43

of the field observed with longer exposure (in four stripes) separating the observations into deep and ultra-deep regions (McCracken et al. 2012) with the CANDELS HST observations inside one of the ultra-deep stripes. The data were pre-processed at CASU,42

which includes dark subtraction, flat fielding, gain normalization, and initial sky subtraction (Irwin et al. 2004; McCracken et al. 2012). The data were further processed at TERAPIX using an iterative sky-background removal technique and resampled to a pixel scale of 0.15 arcsec pixel−1. McCracken et al. (2012) give more details on the data processing. We used the final DR1 mosaics of the UltraVISTA data for the CANDELS multi-wavelength catalog.43

The COSMOS field also has been observed by the NOAO Extremely Wide-Field Infrared Imager (NEWFIRM) on the Mayall 4 m telescope as part of the NEWFIRM Medium Band Survey44

(NMBS; Whitaker et al. 2011). The NEWFRIM observations in the COSMOS cover an area of  encompassing the CANDELS HST observations. The observations are over five medium-band filters of J1, J2, J3, H1, and H2 covering the wavelength of

encompassing the CANDELS HST observations. The observations are over five medium-band filters of J1, J2, J3, H1, and H2 covering the wavelength of  and the K filter centered at 2.2 μm. The three medium-band J1, J2, and J3 filters are a single broadband J filter split into three and the two medium-band H1 and H2 filters combine into a single broadband H (van Dokkum et al. 2009; Whitaker et al. 2011). The final mosaic has a pixel scale of 0.3 arcsec pixel−1. Whitaker et al. (2011) further discuss the data processing. Here we used the first data release of the NMBS data (DR1) of the COSMOS field available from the NOAO science archive.45

and the K filter centered at 2.2 μm. The three medium-band J1, J2, and J3 filters are a single broadband J filter split into three and the two medium-band H1 and H2 filters combine into a single broadband H (van Dokkum et al. 2009; Whitaker et al. 2011). The final mosaic has a pixel scale of 0.3 arcsec pixel−1. Whitaker et al. (2011) further discuss the data processing. Here we used the first data release of the NMBS data (DR1) of the COSMOS field available from the NOAO science archive.45

2.3. Spitzer Infrared Observations

The COSMOS field was observed by the Spitzer Space Telescope IRAC instrument (Fazio et al. 2004) at 3.6 μm, 4.5 μm, 5.8 μm, and 8.0 μm as part of the S-COSMOS (Sanders et al. 2007). The 3.6 μm and 4.5 μm bands have much deeper data from the Spitzer Extended Deep Survey46

(SEDS; Ashby et al. 2013). The SEDS observations cover a strip of  oriented north–south coinciding with the deep VISTA data mentioned above and incorporate previous 3.6 μm and 4.5 μm data from the S-COSMOS providing a uniform depth of 26 mag (3σ) for all observations (Ashby et al. 2013). The 5σ limiting magnitude and FWHM size of the PSF in each IRAC band are reported in Table 1. In this work we used the SEDS first data release (V1.2) (Ashby et al. 2013) available from https://www.cfa.harvard.edu/SEDS/data.html for photometry measurements in the 3.6 μm and 4.5 μm bands and the S-COSMOS Spitzer/IRAC 5.8 μm and 8.0 μm GO2 (V2) data (Sanders et al. 2007) available from http://irsa.ipac.caltech.edu/data/SPITZER/S-COSMOS/. Figure 2 shows the sky coverage of the different ground-based and space data in the COSMOS CANDELS.

oriented north–south coinciding with the deep VISTA data mentioned above and incorporate previous 3.6 μm and 4.5 μm data from the S-COSMOS providing a uniform depth of 26 mag (3σ) for all observations (Ashby et al. 2013). The 5σ limiting magnitude and FWHM size of the PSF in each IRAC band are reported in Table 1. In this work we used the SEDS first data release (V1.2) (Ashby et al. 2013) available from https://www.cfa.harvard.edu/SEDS/data.html for photometry measurements in the 3.6 μm and 4.5 μm bands and the S-COSMOS Spitzer/IRAC 5.8 μm and 8.0 μm GO2 (V2) data (Sanders et al. 2007) available from http://irsa.ipac.caltech.edu/data/SPITZER/S-COSMOS/. Figure 2 shows the sky coverage of the different ground-based and space data in the COSMOS CANDELS.

Figure 2. Sky coverage of data in the COSMOS field. The WFC3 F160W mosaics are shown as the grey shaded region. The entire WFC3 footprint is covered by the CFHT, Subaru, and UltraVISTA observations (which are much larger than the scales of this figure).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image3. Catalog Photometry

In generating the multi-wavelength catalog, the high-resolution data (HST/ACS and WFC3) were treated differently from the low-resolution data (ground-based and Spitzer/IRAC).

3.1. HST Photometry

We performed photometry on the high-resolution (ACS + WFC3) data using SExtractor software version 2.8.6 (Bertin & Arnouts 1996) in dual mode with the WFC3 F160W as the detection band consistently with the multi-wavelength catalogs in the other four CANDELS fields (Galametz et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013). SExtractor software was modified in several ways to enhance the sky measurement, add a new cleaning procedure, and fix isophotal-corrected magnitude calculations as discussed by Galametz et al. (2013). In order to measure the photometry in the visible bands we PSF-matched the ACS and WFC3 images and extracted the photometry from the matched images in dual mode.

As shown in the photometric studies of the CANDELS UDS and CANDELS GOODS-S fields (Galametz et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013), it is impossible to identify all galaxies using a single set of parameters (signifying the area, signal to noise, background, etc.) for the extraction. The challenge is to detect the brightest targets while avoiding blending and also detect the faintest objects without introducing spurious sources into the catalog. To this end we used two sets of SExtractor input parameters. One set of parameters is aimed at bright source detection with a focus on deblending extended sources (cold mode), and a second set on faint galaxies (hot mode). The two catalogs generated by the hot and cold parameters were then combined following a routine adopted from GALAPAGOS47 (Barden et al. 2012). The combined catalog includes all the sources from the cold-mode catalog plus sources in the hot-mode catalog that do not exist in the cold mode as identified by the Kron ellipse of a cold mode detected source as discussed by Galametz et al. (2013). Figure 3 shows the 1σ detection limit of the combined catalog computed over a circular aperture with a radius of 1 arcsec along with the cumulative distribution of the detection area and the exposure time distribution in the F160W band. Figure 4 shows the magnitude distribution of the sources in the hot, cold, and combined catalogs along with the comparison of the F160W combined counts with the CANDELS UDS (Galametz et al. 2013) and 3D-HST (Skelton et al. 2014). Table 3 gives the number counts in magnitude bins for the combined catalog along with the associated Poissonian uncertainties.

Figure 3. Left: the 1σ limiting magnitude distribution (per bin of 0.01) in the WFC3 F160W detection band in each pixel normalized to an area of 1 arcsec2. Middle: cumulative distribution of the area with a sensitivity greater than a given 1σ limiting magnitude. Right: distribution of the exposure time.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 4. Left: the number of galaxies in the CANDELS COSMOS catalog in bins of F160W magnitude (black filled circles). The number counts of the cold-mode selected galaxies (bright sample) and hot-mode-only selected galaxies (faint sample) are shown in blue and red, respectively. The uncertainties associated with the total counts are Poisson errors. The counts and the associated uncertainties are reported in Table 3. Right: number counts of the combined CANDELS COSMOS catalog compared to the CANDELS UDS (Galametz et al. 2013) and the 3D-HST COSMOS (Skelton et al. 2014).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 3. HST/WFC3 F160W Number Counts from the Combined Hot+Cold Catalog

| WFC3 F160Wa | N( ) ) |

Poisson Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|

| 15.25 | 70 | 50 |

| 15.75 | 387 | 117 |

| 16.25 | 563 | 141 |

| 16.75 | 633 | 149 |

| 17.25 | 1196 | 205 |

| 17.75 | 1653 | 241 |

| 18.25 | 2638 | 305 |

| 18.75 | 3166 | 334 |

| 19.25 | 4960 | 418 |

| 19.75 | 6965 | 495 |

| 20.25 | 9990 | 593 |

| 20.75 | 13789 | 696 |

| 21.25 | 17377 | 782 |

| 21.75 | 27086 | 976 |

| 22.25 | 33735 | 1089 |

| 22.75 | 44956 | 1257 |

| 23.25 | 62720 | 1485 |

| 23.75 | 82841 | 1707 |

| 24.25 | 106200 | 1933 |

| 24.75 | 133426 | 2166 |

| 25.25 | 156045 | 2343 |

| 25.75 | 178769 | 2508 |

| 26.25 | 201810 | 2664 |

Note.

aBin center magnitude.Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

At this stage we also assigned a photometry flag to every object in the catalog. The flagging system is the same as that adopted by the other CANDELS fields (Galametz et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013) and discussed in detail by Galametz et al. (2013). We use a zero for a good photometry in the flagging and assigned a value of one for bright stars and spikes associated with those stars as photometry for objects contaminated by this would be unreliable. A photometric flag of two is associated with the edges of the image as measured from the F160W rms maps.

3.2. Ground-based and Spitzer Photometry

In order to measure the photometry in the ground-based and Spitzer bands, we used the Template FITting method (TFIT; Laidler et al. 2007) similarly to the other CANDELS multi-wavelength catalogs (Galametz et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013, M. Stefanon et al. 2017, in preparation). TFIT is a robust algorithm for measuring photometry in mixed-resolution data sets. Sources that are well separated in the high-resolution image (HST) could be blended in the low-resolution image (ground-based or Spitzer). TFIT uses position and light profiles from the high-resolution image to calculate templates that are used to measure the photometry in the low-resolution image. It does that by smoothing the high-resolution image to match the PSF of the low-resolution image using a convolution kernel (Galametz et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013). Fluxes in the low-resolution image are then measured using these templates while fitting the sources simultaneously.

TFIT requires some pre-processing of low-resolution image in terms of orientation and pixel scale. The individual steps taken are as follows.

Background Subtraction: The low-resolution images must be background subtracted before running TFIT. We used a background subtraction routine with several iterations that included a first estimate through smoothing the image on large scales followed by PSF smoothing and source masking that led to a noise map that was interpolated to determine the background (Galametz et al. 2013).

Image Scale: TFIT requires the low-resolution image pixel scale to be an integer multiple of the high-resolution detection image (0.06 arcsec pixel−1 for the F160W) and that both images have the same orientation. Furthermore, the astrometry of the low-resolution images must be consistent with the high-resolution observations. We used SWARP to resample low-resolution data sets to the next larger pixel scale that is an integer multiple of the WFC3 mosaic and also used it for astrometry and image alignment.

Point-spread Function and Kernel: The point-spread function of both the high-resolution and low-resolution images are needed for the TFIT pre-processing. We constructed the PSF by stacking isolated and unsaturated stars in each band using custom IDL routines. We also constructed a kernel to convolve the high-resolution templates to the low-resolution ones. The kernel was constructed using a Fourier space analysis technique similar to Galametz et al. (2013), which takes the ratio of the Fourier transform of each PSF. This gives the Fourier transform of the kernel, which is then transformed back into normal space generating the kernel. As discussed by Galametz et al. (2013) a low passband filter is applied in the Fourier space to cancel the high-frequency fluctuations and remove the effect of noise. For Spitzer/IRAC, which has the largest difference in resolution from HST, one could use the PSFs directly as the convolution kernel (Galametz et al. 2013). We generated a model PSF by averaging a set of oversampled PSFs that measure PSF variations across the detector. The final PSF is a boxcar kernel smoothed and flux normalized model, which also incorporates all the PAs associated with different Astronomical Observation Requests (AORs). We refer the reader to Galametz et al. (2013) and Guo et al. (2013) for more detail.

Dilation Correction for High Resolution Images: TFIT uses the area of the Galaxy identified from the high-resolution HST bands to measure the photometry. These are pixels defined by the high-resolution segmentation maps and are fed into TFIT in the form of the isophotal areas of the high-resolution image. However, as demonstrated by Galametz et al. (2013) and previously by De Santis et al. (2007), SExtractor usually underestimates the isophotal area of faint or small galaxies, and this leads to an underestimate of the flux for such systems. Galametz et al. (2013) performed extensive tests to quantify and correct for this effect, the so-called "dilation correction," by refining and applying the public dilate code (De Santis et al. 2007). These simulations showed that the correction factor is negligible for objects with large isophotal areas and that it is largest for objects with area <60 pixels. The original isophotal area size from SExtractor hence defines the dilation factor applied. We used the same criteria to correct our high-resolution SExtractor segmentation maps as outlined by Galametz et al. (2013) and refer the reader to this work for further details. Even after this correction, the total flux measurement is always bound by uncertainties incorporated into the above assumptions and this constitutes one of the limitations of photometry estimation.

We ran TFIT in two stages. During the first step TFIT measured any remaining misalignment in the form of distortion or mis-registration between the high-resolution and low-resolution images in the form of shifted kernels (Laidler et al. 2007; Galametz et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2013). In the second step, TFIT used the kernels measured from the first step to correct the misalignment and construct a difference residual map of the low-resolution bands. Figure 5 shows the TFIT residual maps in the low-resolution visible, near-infrared, and infrared bands along with the high-resolution F160W detection band. The residual maps in the visible and near-infrared are close to zero and only show residuals in the center of very bright objects. However, as argued by Guo et al. (2013), the residual maps are qualitative representations of the TFIT photometry measurements, and we later show in our data quality checks that the photometry is properly measured for these bright objects. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the PSF FWHMs used for the high- and low-resolution images.

Figure 5. WFC3 F160W source selection band (top left) along with TFIT residual maps in the optical (top right), near-infrared (bottom left) and IRAC infrared (bottom right). The maps all show the same area as the WFC3 F160W band, are in μJy/pixel units, and are all scaled linearly as shown by the respective color bars. The background noise for the Subaru V, UltraVISTA Y, and IRAC 3.6 μm are at the levels of 0.001 μJy, 0.004 μJy, and 0.006 μJy, respectively (images are background subtracted as discussed in Section 3). The arrow marked on the WFC3 maps shows a reference object at a flux density of 74 μJy.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe final F160W SExtractor catalog has 38671 sources over the 216 arcmin2 area of the CANDELS COSMOS field with WFC3 F160W observations. TFIT keeps the original F160W SExtractor ID and coordinates for each object in the combined hot+cold catalog and therefore we only need to combine corresponding entries from the high-resolution and low-resolution catalogs. Figure 6 shows the 5σ limiting depth for all the filters in the catalog as computed and tabulated in Tables 1 and 2. We further derive and report a weight for each target in the catalog calculated from the F160W rms maps at the SExtractor positions for each object as described in Guo et al. (2013).

Figure 6. 5σ limiting magnitude of the different observations in the CANDELS COSMOS (Tables 1 and 2) as a function of the wavelength. The symbol sizes are proportional to the filter response function widths.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4. Data Quality Checks

We checked the TFIT measured photometry by comparing it with other independently measured photometry in the field. Additionally we checked the colors of point sources in the catalog against model predictions and color–color plots.

4.1. Stars Color Checks

The color of stars changes as a function of their spectral type, which in turn depends on the mass (and hence temperature) among other parameters (Kurucz 1979; Vandenberg 1985; Baraffe et al. 1998). Using this, we could compare the measured color of the point-like objects in our catalog against predictions of the colors of stars derived from stellar physics. The predicted colors of stars were computed from the stellar library of BaSeL (Lejeune et al. 1997; Westera et al. 2002) to measure the model stellar colors. We present the comparisons on color–color plots using several observed filters. To measure the predicted photometry from the templates, we integrated the model stellar SED over the wavelength range of each filter taking into account the filter response functions. This provides the predicted colors of point sources. Figure 7 shows our TFIT measured colors for the point-like objects compared to the colors from the BaSeL stellar library. The color trend of our point-like objects agrees with the general distribution of colors predicted by the stellar models. This further confirms our measured photometry, specifically for the brighter sources, and shows no systematic bias in the photometry. The scatter at the redder color is mostly associated with the fainter sources in the catalog and also due to the intrinsic scatter of colors inherent to the library because of the degeneracies among the different populations of stars.

Figure 7. Color–color diagrams showing the TFIT color of stars (determined from SExtractor as objects with  and

and  mag) in CANDELS COSMOS (blue) and model stars from the BaSeL library (black) (Lejeune et al. 1997; Westera et al. 2002). The model colors of stars were computed in each filter by integrating the model SED of stars from the library over the filter transmission curves while the observed colors of the stars are directly from the TFIT catalog with no SED inferred zero-point corrections (Table 5) applied. The filters used are from http://cosmos.astro.caltech.edu/page/filterset.

mag) in CANDELS COSMOS (blue) and model stars from the BaSeL library (black) (Lejeune et al. 1997; Westera et al. 2002). The model colors of stars were computed in each filter by integrating the model SED of stars from the library over the filter transmission curves while the observed colors of the stars are directly from the TFIT catalog with no SED inferred zero-point corrections (Table 5) applied. The filters used are from http://cosmos.astro.caltech.edu/page/filterset.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4.2. Infrared Color Validation Check

A validation check of the infrared colors of objects in the catalog was done by using the Spitzer/IRAC TFIT measured photometry of galaxies to identify luminous active galactic nuclei (AGNs). Mid-infrared observations of galaxies have been used extensively to identify and study AGN host galaxies (e.g., Laurent et al. 2000; Farrah et al. 2007; Petric et al. 2011; Yan et al. 2013; Lacy et al. 2015). Several recent studies have used wide and deep observations in the mid-infrared by Spitzer/IRAC to successfully identify large samples of AGNs using flux ratios (Lacy et al. 2004, 2007; Stern et al. 2005, 2012; Donley et al. 2012; Messias et al. 2012). These color selections are based on the power-law behavior of the mid-infrared continuum of luminous AGNs caused by heated dust, producing a thermal continuum (Neugebauer et al. 1979; Ivezić et al. 2002; Donley et al. 2012; Messias et al. 2012).

Figure 8 shows the TFIT-measured IRAC color distributions of galaxies in our catalog that have a  in all four channels. According to these selections the red IRAC colors are expected to be dominated by emission from AGN-heated dust, as also predicted by previous studies of SDSS and radio-selected quasars (Lacy et al. 2004), whereas any stellar components usually shifts the

in all four channels. According to these selections the red IRAC colors are expected to be dominated by emission from AGN-heated dust, as also predicted by previous studies of SDSS and radio-selected quasars (Lacy et al. 2004), whereas any stellar components usually shifts the  ratio to bluer colors. The Donley et al. (2012) criteria are more conservative in selecting AGNs by removing star-forming and quiescent galaxies identified through other selection methods from optical and near-infrared observations (such as the BzK and LBG selections; Madau et al. 1996; Giavalisco 2002). Figure 8 also shows the IRAC color distribution of the X-ray detected sources in COSMOS (Cappelluti et al. 2007) along with the IRAC color distribution of point sources. The majority of the X-ray detected AGNs have IRAC color distributions consistent with the selections by Lacy et al. (2004) and Donley et al. (2012). As discussed by Donley et al. (2012), not all the X-ray luminous and IRAC detected sources are identified by AGN color criteria. In fact, Donley et al. (2012) argue that the X-ray-detected QSOs that fall outside the color criteria seem to be more heavily obscured with lower luminosity AGNs such that the host galaxy contributes more to the optical-near-IR flux. The stellar sources and the general population, however, follow different IRAC color distributions as demonstrated by Lacy et al. (2004) and Donley et al. (2012). We also present a check of stellar colors using IRAC 3.6 μm and 4.5 μm bands in Section 6.2 and Figure 22, where our photometry is found to be consistent with synthetic colors.

ratio to bluer colors. The Donley et al. (2012) criteria are more conservative in selecting AGNs by removing star-forming and quiescent galaxies identified through other selection methods from optical and near-infrared observations (such as the BzK and LBG selections; Madau et al. 1996; Giavalisco 2002). Figure 8 also shows the IRAC color distribution of the X-ray detected sources in COSMOS (Cappelluti et al. 2007) along with the IRAC color distribution of point sources. The majority of the X-ray detected AGNs have IRAC color distributions consistent with the selections by Lacy et al. (2004) and Donley et al. (2012). As discussed by Donley et al. (2012), not all the X-ray luminous and IRAC detected sources are identified by AGN color criteria. In fact, Donley et al. (2012) argue that the X-ray-detected QSOs that fall outside the color criteria seem to be more heavily obscured with lower luminosity AGNs such that the host galaxy contributes more to the optical-near-IR flux. The stellar sources and the general population, however, follow different IRAC color distributions as demonstrated by Lacy et al. (2004) and Donley et al. (2012). We also present a check of stellar colors using IRAC 3.6 μm and 4.5 μm bands in Section 6.2 and Figure 22, where our photometry is found to be consistent with synthetic colors.

Figure 8. IRAC color–color diagram and the AGN selection criteria from Lacy et al. (2004; dashed magenta line) and Donley et al. (2012; solid magenta line). Black circles are galaxies from the catalog with  in all four IRAC bands. Sources with

in all four IRAC bands. Sources with  and

and  are shown by yellow circles. X-ray point-like detected sources from XMM-Newton wide-field observations of COSMOS (Brusa et al. 2010) are shown by large blue circles.

are shown by yellow circles. X-ray point-like detected sources from XMM-Newton wide-field observations of COSMOS (Brusa et al. 2010) are shown by large blue circles.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4.3. Validation Checks with Public Photometry

We also checked the TFIT photometry by comparing it with the public photometry available from the 3D-HST survey48

(Skelton et al. 2014). The 3D-HST photometry was measured by SExtractor on PSF-matched combined HST/WFC3 images in three bands (F125W, F140W, and F160W) as the detection (Skelton et al. 2014). The HST images were reduced similarly to CANDELS using the same pixel scale and tangent point (Skelton et al. 2014). Photometry on the low-resolution bands was performed using the MOPHONGO code (Labbé et al. 2005, 2006; Wuyts et al. 2007; Labbé et al. 2013), which takes into account the variations in the PSF size across different filters and in particular the source confusion problem in the low-resolution images by using a combined PSF-matched WFC3 images as a high-resolution image prior for photometry estimation (Labbé et al. 2005; Skelton et al. 2014). The 3D-HST adjusted the AUTO fluxes by an aperture correction derived from growth curves and furthermore performed Galactic extinction corrections. The Galactic extinction correction was measured at the center of each filter and was based on Finkbeiner et al. (1999). These corrections are relatively small ( Table 5 in Skelton et al. 2014). We took this into account when comparing our fluxes with that of the 3D-HST. All fluxes in the 3D-HST catalogs were converted to AB magnitudes using a zero-point of 25 (Skelton et al. 2014).

Table 5 in Skelton et al. 2014). We took this into account when comparing our fluxes with that of the 3D-HST. All fluxes in the 3D-HST catalogs were converted to AB magnitudes using a zero-point of 25 (Skelton et al. 2014).

Figure 9 shows the comparison between TFIT measured photometry and the public photometry from the 3D-HST. For the source matching we used a radius equal to the FWHM size of the PSF in the F160W ( ). We find good agreement between the measured fluxes in our catalog and that of the 3D-HST. The offset is generally

). We find good agreement between the measured fluxes in our catalog and that of the 3D-HST. The offset is generally  mag. There is, however, a magnitude-dependent trend when comparing the CANDELS and 3D-HST photometry. This is related to the difference in the photometry extraction between the CANDELS (TFIT) and the 3D-HST (aperture photometry with fixed apertures for each band; Tables 4–8 of Skelton et al. 2014). Figure 10 shows the comparison between CANDELS COSMOS TFIT measured

mag. There is, however, a magnitude-dependent trend when comparing the CANDELS and 3D-HST photometry. This is related to the difference in the photometry extraction between the CANDELS (TFIT) and the 3D-HST (aperture photometry with fixed apertures for each band; Tables 4–8 of Skelton et al. 2014). Figure 10 shows the comparison between CANDELS COSMOS TFIT measured  color and the corresponding colors of sources measured from the 3D-HST catalog (Skelton et al. 2014) as a function of the F160W magnitude. For both catalogs the F160W band is taken as the reference band for measuring the color. While comparing the

color and the corresponding colors of sources measured from the 3D-HST catalog (Skelton et al. 2014) as a function of the F160W magnitude. For both catalogs the F160W band is taken as the reference band for measuring the color. While comparing the  color for the different fields as a function of photometric redshift, we noticed a deviation of ∼0.6 mag between the colors in the COSMOS and GOODS-S fields for the red objects in the Spitzer 8.0 μm band. There is an offset (though smaller) in similar color between the 3D-HST COSMOS and GOODS-S fields. Looking at the variation of this color difference between the CANDELS COSMOS and 3D-HST as a function of the F160W, we notice that most of the difference is associated with objected fainter than ∼22 mag, which is similar to our 5σ detection limit.

color for the different fields as a function of photometric redshift, we noticed a deviation of ∼0.6 mag between the colors in the COSMOS and GOODS-S fields for the red objects in the Spitzer 8.0 μm band. There is an offset (though smaller) in similar color between the 3D-HST COSMOS and GOODS-S fields. Looking at the variation of this color difference between the CANDELS COSMOS and 3D-HST as a function of the F160W, we notice that most of the difference is associated with objected fainter than ∼22 mag, which is similar to our 5σ detection limit.

Figure 9. Photometry comparison between CANDELS and 3D-HST (Skelton et al. 2014). The grayscale density map shows all sources and the magenta shows point sources (identified with SExtractor  and

and  mag). The thick and thin cyan lines show the median of the distribution and the corresponding 1σ confidence intervals. The number reported in each panel represents the median of the offset for the bright end of the distribution between the CANDELS and the 3D-HST photometry (arbitrarily chosen to be

mag). The thick and thin cyan lines show the median of the distribution and the corresponding 1σ confidence intervals. The number reported in each panel represents the median of the offset for the bright end of the distribution between the CANDELS and the 3D-HST photometry (arbitrarily chosen to be  mag).

mag).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 10. Color comparison of the CANDELS COSMOS and the 3D-HST (Skelton et al. 2014) as a function of the F160W magnitude. Each panel shows the difference of the (Band-F160W) color between CANDELS and 3D-HST (with F160W being the reference band for calculating the colors in both). The cyan lines show the median and 1σ variations in the color difference. Point sources in the plot are shown as magenta data points and the median of the offset is reported at the bottom left of each panel.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5. Photometric Redshift and Stellar Mass Estimates

The methods we used to measure the photometric redshifts and stellar masses are presented in Dahlen et al. (2013) and Mobasher et al. (2015), respectively. Measurements of these parameters are carried out for other CANDELS fields, including CANDELS UDS, CANDELS GOODS-S (Santini et al. 2015), CANDELS EGS (M. Stefanon et al. 2017, in preparation), and CANDELS GOODS-N (G. Barro et al. 2017, in preparation).

5.1. Photometric Redshifts

We provided the CANDELS COSMOS photometric catalog to individual teams in the collaboration. The teams were asked to estimate photometric redshifts to galaxies using a calibrating sample containing spectroscopic redshifts. The spectroscopic redshifts were taken from the zCOSMOS compilation (Lilly et al. 2007). Only redshifts for sources in the CANDELS COSMOS area with clear emission-line features were used with uncertain redshifts left out. The spectroscopic redshifts used here are all in public domain. However, for training purposes, a larger sample of unpublished spectroscopic redshifts were used from zCOSMOS (M. Salvato 2016, private communication). Measurements from different teams are in good agreement and also agreed with an independent sample of 448 high-quality spectroscopic redshifts not used to calibrate the photometric redshift methods. A total of six individuals participated. Methods included various fitting codes using minimum  and MCMC along with varying Star Formation Histories (SFH). The details of these methods are outlined in Table 7 in the Appendix. Using simulations, we showed that one could determine redshifts to an accuracy of 0.025 in

and MCMC along with varying Star Formation Histories (SFH). The details of these methods are outlined in Table 7 in the Appendix. Using simulations, we showed that one could determine redshifts to an accuracy of 0.025 in  . For each galaxy, we derived the median redshift from different methods and considered that as the redshift estimate for that galaxy. The confidence intervals were measured by combining the intervals from different methods, following the procedure used by Dahlen et al. (2013). Taking the median of the photometric redshifts does not necessarily produce a better measurement as this depends heavily on the codes and templates used in calculating the redshift and the corresponding scatter when compared to the spectroscopic redshifts. Comparing with an independent sample of spectroscopic redshifts not used for photometric redshift training, we find that while taking the median reduces the outlier fractions compared to some of the individual codes, marginally lower outlier fractions are obtained using only a subset of the codes (those of Wuyts, Gruetzbach, and Salvato for this field). Given the relatively small number of spectroscopic redshifts available for this test (262), we do not consider the difference significant and choose to report the median of all the codes as our recommended best photometric redshift. Figure 11 shows a direct comparison between the photometric and spectroscopic redshifts for galaxies in the CANDELS COSMOS field, only using high quality spectroscopic redshifts. The training was done using a larger sample of spectroscopic redshifts in CANDELS COSMOS area from the zCOSMOS survey. These do not overlap with the comparison sample here, which is a smaller subsample that is in public domain. Figure 12 shows the spectroscopic redshift distributions of the training and comparison samples. The high-quality spectroscopic redshifts used for the training of the photometric redshifts are available over the range

. For each galaxy, we derived the median redshift from different methods and considered that as the redshift estimate for that galaxy. The confidence intervals were measured by combining the intervals from different methods, following the procedure used by Dahlen et al. (2013). Taking the median of the photometric redshifts does not necessarily produce a better measurement as this depends heavily on the codes and templates used in calculating the redshift and the corresponding scatter when compared to the spectroscopic redshifts. Comparing with an independent sample of spectroscopic redshifts not used for photometric redshift training, we find that while taking the median reduces the outlier fractions compared to some of the individual codes, marginally lower outlier fractions are obtained using only a subset of the codes (those of Wuyts, Gruetzbach, and Salvato for this field). Given the relatively small number of spectroscopic redshifts available for this test (262), we do not consider the difference significant and choose to report the median of all the codes as our recommended best photometric redshift. Figure 11 shows a direct comparison between the photometric and spectroscopic redshifts for galaxies in the CANDELS COSMOS field, only using high quality spectroscopic redshifts. The training was done using a larger sample of spectroscopic redshifts in CANDELS COSMOS area from the zCOSMOS survey. These do not overlap with the comparison sample here, which is a smaller subsample that is in public domain. Figure 12 shows the spectroscopic redshift distributions of the training and comparison samples. The high-quality spectroscopic redshifts used for the training of the photometric redshifts are available over the range  and hence photometric redshifts reported are most reliable for that redshift range. The values of the redshift difference, as defined in Dahlen et al. (2013), along with the outlier fractions are listed in Table 4. As mentioned above, reliable spectroscopic redshifts are available out to

and hence photometric redshifts reported are most reliable for that redshift range. The values of the redshift difference, as defined in Dahlen et al. (2013), along with the outlier fractions are listed in Table 4. As mentioned above, reliable spectroscopic redshifts are available out to  and the numbers listed in Table 4 are only representative for galaxies in this range.

and the numbers listed in Table 4 are only representative for galaxies in this range.

Figure 11. Comparison between photometric redshift and spectroscopic redshift for the CANDELS, COSMOS (Ilbert et al. 2013), and the 3D-HST (Skelton et al. 2014). The CANDELS photometric redshift correspond to the median value measured by the different methods.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 12. Spectroscopic redshift distributions of the training set used to calibrate the photometric redshifts (in blue) and the independent comparison set (in red).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 4. Spectroscopic Redshift Comparison Table

| Survey | OLFa |

b

b

|

c

c

|

d

d

|

Number of Galaxiese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CANDELS COSMOS | 0.008 | 0.035 | 0.011 | 0.016 | 506 |

| COSMOS Team | 0.05 | 0.071 | 0.008 | 0.017 | 504 |

| 3D-HST | 0.012 | 0.045 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 499 |

Notes.

aDefined as fraction of objects with where

where  (Dahlen et al. 2013).

b

(Dahlen et al. 2013).

b

.

c

.

c

.

d

.

d

after removing the outliers.

ewith reliable spectroscopic redshift used for the comparison. This is for objects with

after removing the outliers.

ewith reliable spectroscopic redshift used for the comparison. This is for objects with  and hence the reported numbers are valid for this redshift range where high quality spectroscopic redshifts are available.

and hence the reported numbers are valid for this redshift range where high quality spectroscopic redshifts are available.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

We cross-compared the CANDELS photometric redshift catalog with those from COSMOS (Ilbert et al. 2013) and 3D-HST (Skelton et al. 2014). Figure 11 shows the comparison between the photometric and spectroscopic redshifts in the COSMOS and 3D-HST catalogs. The rms values are listed in Tableapjsaa53b1t4 4 and show similar trends as CANDELS COSMOS. We compare photometric redshifts between the CANDELS COSMOS and those from the COSMOS (Ilbert et al. 2013) and 3D-HST (Skelton et al. 2014) catalogs, in Figure 13. The two photometric redshift comparison plots present the full scatter ( ), the normalized median absolute deviation (

), the normalized median absolute deviation ( ) and the scatter after excluding outliers (

) and the scatter after excluding outliers ( ) as well as the outlier fraction (defined as fraction of objects with

) as well as the outlier fraction (defined as fraction of objects with  ). There is consistency in the photometric redshift measurements for the majority of galaxies. The spread seen in Figure 13, is due to log-binning of the histograms and does not indicate any large inconsistency. Table 5 shows the photometric offsets measured from SED fitting for different bands. The offsets are measured through the SED fitting, simultaneously with photometric redshifts. Different independent SED fitting methods estimated the offsets and they agreed fairly well. The magnitude offsets were then used in the photometry to estimate the final photometric redshifts. The photometric redshifts have the correction for the photometric offsets, but the photometry presented here is not corrected for the offset.

). There is consistency in the photometric redshift measurements for the majority of galaxies. The spread seen in Figure 13, is due to log-binning of the histograms and does not indicate any large inconsistency. Table 5 shows the photometric offsets measured from SED fitting for different bands. The offsets are measured through the SED fitting, simultaneously with photometric redshifts. Different independent SED fitting methods estimated the offsets and they agreed fairly well. The magnitude offsets were then used in the photometry to estimate the final photometric redshifts. The photometric redshifts have the correction for the photometric offsets, but the photometry presented here is not corrected for the offset.

Figure 13. Photometric redshift comparison plots of CANDELS COSMOS with 3D-HST (left) and COSMOS (right) catalogs. The comparison is shown in the form of a 2D histogram with logarithmic bins to help see the small outlier fraction. The sub-panels in both plots show  as a function of CANDELS photometric redshifts, where

as a function of CANDELS photometric redshifts, where  for photometric redshift measurements.

for photometric redshift measurements.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 5. SED Fitting Measured Photometric Offsets

| Filter | Median Offseta |

|---|---|

| (AB Mag) | |

| CFHT-u* | 0.041 |

| CFHT-g* | −0.044 |

| CFHT-r* | −0.005 |

| CFHT-i* | −0.025 |

| CFHT-z* | 0.000 |

| Subaru-B | −0.004 |

Subaru-

|

−0.071 |

Subaru-

|

−0.074 |

Subaru-

|

−0.150 |

| ACS-F606W | 0.072 |

| ACS-F814W | 0.019 |

| WFC3 F125W | 0.104 |

| WFC3 F160W | 0.091 |

| UVISTA-Y | −0.027 |

| UVISTA-J | 0.046 |

| UVISTA-H | 0.067 |

| UVISTA-Ks | −0.031 |

| IRAC-3.6 μm | −0.061 |

| IRAC-4.5 μm | −0.176 |

| IRAC-5.8 μm | −0.069 |

| IRAC-8.0 μm | −0.697 |

| NEWFIRM-J1 | −0.061 |

| NEWFIRM-J2 | −0.027 |

| NEWFIRM-J3 | 0.000 |

| NEWFIRM-H1 | −0.025 |

| NEWFIRM-H2 | −0.060 |

| NEWFIRM-K | −0.073 |

Note.

aPositive offset: measured flux fainter than expected from template.Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

One method for estimating the photometric redshift uncertainties that is specially useful for fainter flux limits where not enough spectroscopic redshift information is available is the pair statistics estimates (Quadri & Williams 2010; Dahlen et al. 2013; Huang et al. 2013; Hsu et al. 2014). The method, as outlined in Dahlen et al. (2013), relies on the fact that spatially close pairs (defined as objects with separation less than 15 arcsec) have a high probability of being associated with each other and therefore being at similar redshifts (Dahlen et al. 2013). This close-pair association would show up as excess power at small separations when compared to the distribution based on random galaxies (Dahlen et al. 2013). Figure 14 shows the random and close-pair photometric redshift difference distribution along with the excess distribution of the close pairs in photometric redshift after subtracting the photometric redshift distribution of the random galaxies. By fitting a Gaussian function to this excess distribution we measured an uncertainty of 0.017 ( ) in the photometric redshift distribution.

) in the photometric redshift distribution.

Figure 14. Top: distribution of the photometric redshift difference for the random pair (black) and the close pairs, defined as objects with separation less than 15 arcsec (blue). Bottom: distribution of the overdensity of the photometric redshift difference for close pairs. The distribution is observed in excess of the photometric redshift difference distribution of random galaxies that are subtracted (top panel; Dahlen et al. 2013). A Gaussian fit to the distribution gives the uncertainties associated with the redshifts. This test only characterizes the core of the photometric redshift errors and not the outlier rate.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5.2. Stellar Masses

Mobasher et al. (2015) studied stellar mass measurement using CANDELS data. With extensive simulations, they explored different sources of uncertainty in stellar mass measurements and estimated the error budget associated with them. The stellar masses were measured from different methods independently and were compared with their expected (input) mass. All methods produced stellar masses in good agreement. We use the median mass (among all the methods) as the reported CANDELS estimate. As we discussed earlier, taking the median does not necessarily produce a more robust mass estimate because the results of individual codes used are not instances of the same stochastic process.

The TFIT multi-waveband photometric catalog for the CANDELS COSMOS field was provided to the CANDELS teams outlined in Tableapjsaa53b1t8 8 and they measured the stellar masses through separate SED fitting techniques. For all the independent measurements, redshifts were fixed to their median values (as described in the previous section). Given that the photometric redshifts are calibrated with a spectroscopic sample with  , the stellar mass estimates are also well calibrated and most robust within this redshift range, as discussed in the previous section, although we report stellar mass estimates out to

, the stellar mass estimates are also well calibrated and most robust within this redshift range, as discussed in the previous section, although we report stellar mass estimates out to  in this catalog. Some of the methods included nebular emission when fitting the SEDs as outlined in Table 8. A total of eight entries were received from different teams. We measured the median stellar mass between different methods. We used the Hodges–Lehmann49

method to estimate the median stellar mass which accounts for the small number of entries when measuring the median value.

in this catalog. Some of the methods included nebular emission when fitting the SEDs as outlined in Table 8. A total of eight entries were received from different teams. We measured the median stellar mass between different methods. We used the Hodges–Lehmann49

method to estimate the median stellar mass which accounts for the small number of entries when measuring the median value.

Figure 15 presents a direct comparison between different methods used to measure stellar masses. Here, we plot estimates from each method against the median from all the rest of the methods. There is good internal consistency between different methods and the tails seen in Figure 15 help identify where the outliers are in each method compared to the rest. These outliers will not bias our measurements as we report the median of all methods for our final stellar mass measurements as demonstrated in Mobasher et al. (2015).

Figure 15. Comparisons of the reported stellar masses using eight different methods outlined in Table 8 vs. the median stellar mass of all the other methods. The plots are shown as 2D histograms with logarithmic bins. We report the variations in the mass difference and the outliers as defined in Section 5.1 in each panel.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe median stellar mass estimates from the CANDELS are compared to those from the COSMOS (Ilbert et al. 2013) and 3D-HST catalogs (Skelton et al. 2014) in Figure 16. In these comparisons, we measure the scatter similarly to the photometric redshift where  and

and  after removing the outliers where outlier fraction is defined as the fraction of objects with

after removing the outliers where outlier fraction is defined as the fraction of objects with  (Mobasher et al. 2015), as shown on Figure 16. The CANDELS stellar mass measurements are consistent with both COSMOS and 3D-HST stellar masses. The stellar mass offsets between CANDELS median measurement and 3D-HST and COSMOS are also plotted as a function of F160W magnitude in Figure 17. As expected, the larger discrepancies between the stellar mass estimates occur at fainter magnitudes. The rms values of the stellar mass estimate offsets as defined above are presented in Table 6 as a function of H-band magnitude, confirming a good agreement at brighter magnitudes and an overall consistency for the majority of galaxies.

(Mobasher et al. 2015), as shown on Figure 16. The CANDELS stellar mass measurements are consistent with both COSMOS and 3D-HST stellar masses. The stellar mass offsets between CANDELS median measurement and 3D-HST and COSMOS are also plotted as a function of F160W magnitude in Figure 17. As expected, the larger discrepancies between the stellar mass estimates occur at fainter magnitudes. The rms values of the stellar mass estimate offsets as defined above are presented in Table 6 as a function of H-band magnitude, confirming a good agreement at brighter magnitudes and an overall consistency for the majority of galaxies.

Figure 16. Stellar mass comparison plots of CANDELS COSMOS with 3D-HST (left) and COSMOS (right) measurements. The comparison is shown in the form of 2D-histogram with logarithmic bins to help see the small outlier fraction. In each panel we report the variations in the mass difference and the outlier fractions as defined in Section 5.1. The sub-panels show  as a function of CANDELS

as a function of CANDELS  where

where  for stellar mass measurement.

for stellar mass measurement.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 17. Stellar mass offsets between CANDELS and 3D-HST (left) and COSMOS (right) as a function of the F160W magnitude. Both plots are in forms of 2D histograms with logarithmic bins, showing the fraction of inconsistent measurements increase at fainter magnitudes.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 6. Variations and Outlier Fractions in Mass Measurements

| Magnitude Cut (AB) | OLFa |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COSMOS | |||||

|

0.032 | 0.307 | 0.124 | 0.149 | |

|

0.048 | 0.309 | 0.138 | 0.153 | |

|

0.077 | 0.384 | 0.179 | 0.175 | |

|

0.172 | 0.549 | 0.251 | 0.204 | |

| 3D-HST | |||||

|

0.049 | 0.597 | 0.133 | 0.131 | |

|

0.054 | 0.463 | 0.138 | 0.144 | |

|

0.089 | 0.563 | 0.148 | 0.148 | |

|

0.138 | 0.687 | 0.201 | 0.179 |

Note.

aDefined as (Mobasher et al. 2015).

(Mobasher et al. 2015).

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

When measuring the stellar mass, we fit the SEDs by fixing redshifts to the median of the photometric redshifts from the CANDELS COSMOS team, as discussed in Section 5.1. Therefore, if the redshifts for the same galaxies are different in those from 3D-HST and COSMOS teams, the effect would propagate to the estimated stellar masses. As a result, the observed offsets between the stellar mass values in Figures 16 and 17 could partly be explained by the discrepancy between the redshifts. To explore this, we studied the residual diagrams between redshifts and stellar masses for the three measurements. For this we look at the ratio of the stellar masses as measured by different methods ( ) as a function of the redshift difference

) as a function of the redshift difference  in Figure 18 showing a 0.25 dex scatter in stellar mass for galaxies with similar redshifts. This is in agreement with results of Mobasher et al. (2015), who measured the combined error budget in stellar mass values due to different parameters. Therefore, the distribution in residual mass here is consistent with the expected uncertainties in the stellar mass measurements (i.e., the vertical scatter). The galaxies with deviant redshifts also have deviant stellar mass estimates, partly explaining the observed scatter between the CANDELS and 3D-HST and CANDELS and COSMOS stellar masses.

in Figure 18 showing a 0.25 dex scatter in stellar mass for galaxies with similar redshifts. This is in agreement with results of Mobasher et al. (2015), who measured the combined error budget in stellar mass values due to different parameters. Therefore, the distribution in residual mass here is consistent with the expected uncertainties in the stellar mass measurements (i.e., the vertical scatter). The galaxies with deviant redshifts also have deviant stellar mass estimates, partly explaining the observed scatter between the CANDELS and 3D-HST and CANDELS and COSMOS stellar masses.

Figure 18. Stellar mass offsets vs. photometric redshifts offsets between CANDELS measurements and those from COSMOS (left) and 3D-HST team (right). The solid red lines show the 1:1 relations.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 19 compares the difference between stellar mass measurements with and without correction for nebular emission lines. This shows a small scatter (0.25 dex) in the stellar mass, consistent with Mobasher et al. (2015), but no significant offset over the whole population over the large redshift range.

Figure 19. Difference of the median of the stellar mass measured with and without nebular emission as a function of the redshift. The dashed red line shows the 1:1 relation. The median and 1σ variations are shown with the light and dark blue respectively. The median is consistent with no evolution as a function of redshift for the two mass estimates.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5.3. Mass Completeness

We use the method introduced by Pozzetti et al. (2010) to estimate the stellar mass completeness limit of the general population of galaxies (see also Ilbert et al. 2013 and Darvish et al. 2015a). Given the magnitude limit of the sample (

limiting magnitude in the F160W detection band), we assigned a limiting stellar mass (

limiting magnitude in the F160W detection band), we assigned a limiting stellar mass ( ) to each galaxy.

) to each galaxy.  is the stellar mass that a galaxy would have at its estimated redshift, if its apparent magnitude was the same as the magnitude limit of our sample (

is the stellar mass that a galaxy would have at its estimated redshift, if its apparent magnitude was the same as the magnitude limit of our sample ( ). This was evaluated by

). This was evaluated by  , where M is the estimated stellar mass of the Galaxy with its apparent magnitude H. This results in a distribution of