Abstract

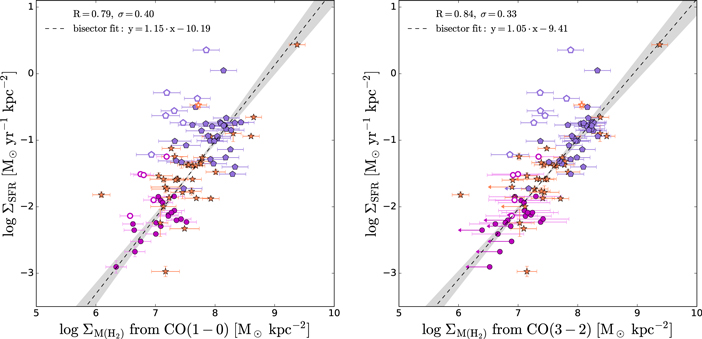

We study the  luminosity line ratio in a sample of nearby (z < 0.05) galaxies: 25 star-forming galaxies (SFGs) from the xCOLD GASS survey, 36 hard X-ray-selected active galactic nucleus (AGN) host galaxies from the BAT AGN Spectroscopic Survey, and 37 infrared-luminous galaxies from the SCUBA Local Universe Galaxy Survey. We find a trend for r31 to increase with star formation efficiency (SFE). We model r31 using the UCL-PDR code and find that the gas density is the main parameter responsible for the variation of r31, while the interstellar radiation field and cosmic-ray ionization rate play only a minor role. We interpret these results to indicate a relation between SFE and gas density. We do not find a difference in the r31 value of SFGs and AGN host galaxies, when the galaxies are matched in SSFR (〈r31〉 = 0.52 ± 0.04 for SFGs and 〈r31〉 = 0.53 ± 0.06 for AGN hosts). According to the results of the UCL-PDR models, the X-rays can contribute to the enhancement of the CO line ratio, but only for strong X-ray fluxes and for high gas density (nH > 104 cm−3). We find a mild tightening of the Kennicutt–Schmidt relation when we use the molecular gas mass surface density traced by CO(3–2) (Pearson correlation coefficient R = 0.83), instead of the molecular gas mass surface density traced by CO(1–0) (R = 0.78), but the increase in correlation is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.06). This suggests that the CO(3–2) line can be reliably used to study the relation between SFR and molecular gas for normal SFGs at high redshift and to compare it with studies of low-redshift galaxies, as is common practice.

luminosity line ratio in a sample of nearby (z < 0.05) galaxies: 25 star-forming galaxies (SFGs) from the xCOLD GASS survey, 36 hard X-ray-selected active galactic nucleus (AGN) host galaxies from the BAT AGN Spectroscopic Survey, and 37 infrared-luminous galaxies from the SCUBA Local Universe Galaxy Survey. We find a trend for r31 to increase with star formation efficiency (SFE). We model r31 using the UCL-PDR code and find that the gas density is the main parameter responsible for the variation of r31, while the interstellar radiation field and cosmic-ray ionization rate play only a minor role. We interpret these results to indicate a relation between SFE and gas density. We do not find a difference in the r31 value of SFGs and AGN host galaxies, when the galaxies are matched in SSFR (〈r31〉 = 0.52 ± 0.04 for SFGs and 〈r31〉 = 0.53 ± 0.06 for AGN hosts). According to the results of the UCL-PDR models, the X-rays can contribute to the enhancement of the CO line ratio, but only for strong X-ray fluxes and for high gas density (nH > 104 cm−3). We find a mild tightening of the Kennicutt–Schmidt relation when we use the molecular gas mass surface density traced by CO(3–2) (Pearson correlation coefficient R = 0.83), instead of the molecular gas mass surface density traced by CO(1–0) (R = 0.78), but the increase in correlation is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.06). This suggests that the CO(3–2) line can be reliably used to study the relation between SFR and molecular gas for normal SFGs at high redshift and to compare it with studies of low-redshift galaxies, as is common practice.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

1. Introduction

Star formation in galaxies is closely related to their gas content. This has been found in the correlation between the star formation rate (SFR) surface density and gas mass surface density (Kennicutt–Schmidt (KS) relation; Kennicutt 1998). The relation between SFR and molecular gas content is stronger than with the total gas content (Bigiel et al. 2008; Leroy et al. 2008; Saintonge et al. 2017). However, there is some scatter in this relation: the SFR surface density can vary by an order of magnitude for the same molecular gas mass surface density, measured from the CO(1–0) luminosity (Saintonge et al. 2012). A possible explanation is that CO(1–0) is a good tracer of the total molecular gas in massive galaxies, but it does not accurately trace the amount of gas located in the dense molecular cores where the formation of stars takes place (e.g., Solomon et al. 1992; Kohno et al. 2002; Shibatsuka et al. 2003). Because stars form in dense molecular clouds, it is reasonable to expect the SFR to correlate better with the amount of dense molecular gas than with the total (dense and diffuse) molecular gas. Commonly used tracers of dense gas are HCN, HCO+, or CS (e.g., Gao & Solomon 2004a, 2004b; Wu et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2014; Tan et al. 2018).

Observations have shown that the HCN(1–0)/CO(1–0) ratio is enhanced in galaxies with high star formation efficiency (SFE = SFR/ ), like luminous infrared galaxies (LIRGs; Gao & Solomon 2004a; Gracia-Carpio et al. 2008; García-Burillo et al. 2012). However, the HCN(1–0) line flux is usually fainter than CO by more than an order of magnitude, making surveys of large samples of normal star-forming galaxies (SFGs) very time consuming. Another option is to use higher CO transitions to trace the mass of dense molecular gas. The ideal transition is CO(3–2): it does not trace low-density gas (critical density ncrit = 3.6 × 104 cm−3, calculated under the optically thin assumption; Carilli & Walter 2013) like the CO(1–0) and CO(2–1) transitions, and at the same time it does not require high temperatures to populate it (the minimum gas temperature needed for significant excitation is Tmin = 33 K; Mauersberger et al. 1999; Yao et al. 2003; Wilson et al. 2009). If the gas density is the key quantity regulating the relation between molecular gas mass and SFR, then we expect to see a correlation between the SFE and the r31

), like luminous infrared galaxies (LIRGs; Gao & Solomon 2004a; Gracia-Carpio et al. 2008; García-Burillo et al. 2012). However, the HCN(1–0) line flux is usually fainter than CO by more than an order of magnitude, making surveys of large samples of normal star-forming galaxies (SFGs) very time consuming. Another option is to use higher CO transitions to trace the mass of dense molecular gas. The ideal transition is CO(3–2): it does not trace low-density gas (critical density ncrit = 3.6 × 104 cm−3, calculated under the optically thin assumption; Carilli & Walter 2013) like the CO(1–0) and CO(2–1) transitions, and at the same time it does not require high temperatures to populate it (the minimum gas temperature needed for significant excitation is Tmin = 33 K; Mauersberger et al. 1999; Yao et al. 2003; Wilson et al. 2009). If the gas density is the key quantity regulating the relation between molecular gas mass and SFR, then we expect to see a correlation between the SFE and the r31 luminosity line ratio, which can be interpreted as an indicator of the gas density.

luminosity line ratio, which can be interpreted as an indicator of the gas density.

The r31 value has been measured in samples of LIRGs (Leech et al. 2010; Papadopoulos et al. 2012), in the central regions of nearby galaxies (Mauersberger et al. 1999; Mao et al. 2010), in submillimeter galaxies (SMGs; Harris et al. 2010), and in nearby galaxies (Wilson et al. 2012). Yao et al. (2003) and Leech et al. (2010) found a trend where r31 increases with increasing SFE in samples of infrared-luminous galaxies and LIRGs. This trend has also been found in spatially resolved observations of M83, NGC 3627, and NGC 5055 (Muraoka et al. 2007; Morokuma-Matsui & Muraoka 2017). Sharon et al. (2016) found a similar trend in a sample of submillimeter galaxies and AGN hosts at redshifts z = 2–3. Most studies of the r31 line ratio focused on extreme objects, like LIRGs, or are limited to small samples. In this work, we collect CO observations for a homogeneous sample of main-sequence galaxies to investigate the r31 line ratio in more "normal" SFGs.

We also analyze a sample of galaxies hosting active galactic nuclei (AGN) to investigate if AGN have an effect on the r31 line ratio of their host galaxy. Several studies of the CO spectral line energy distribution (SLED) of AGN focused on the high-J rotational transition levels. For instance, Lu et al. (2017) studied the CO SLED in the GOALS sample (The Great Observatories All-Sky LIRG Survey; Armus et al. 2009) and found that the presence of an AGN influences only the very high J levels (J > 10). Mashian et al. (2015) found that the CO SLED is not the same in all AGN and that the shape of the CO SLED of a galaxy is more related to the content of warm and dense molecular gas than to the excitation mechanism. Rosenberg et al. (2015) analyzed the CO ladder of 29 objects from the Herschel Comprehensive ULIRG Emission Survey (HerCULES). They find that in objects with a large AGN contribution, the CO ladder peaks at higher J levels, which means that in these objects, the CO excitation is influenced by harder radiation sources (X-rays or cosmic rays). These studies focus mostly on the high J levels (J > 4). Rosario et al. (2018) studied the molecular gas properties, traced by CO(2–1), of a sample of 20 nearby (z < 0.01) hard X-ray-selected AGN hosts from the LLAMA survey and compared it with a control sample of SFGs. They found similar molecular gas fraction and SFE in the central region of AGN and in the control galaxies. Sharon et al. (2016) also compared the r31 values of 15 SMGs and 13 AGN host galaxies at redshifts z = 2–3 and did not find a significant difference.

In this paper, we study the r31 luminosity line ratio in a sample of nearby (z < 0.05) SFGs and AGN. In Sections 2 and 3, we describe the sample and the CO observations. In Section 4, we present the r31 values and analyze the correlation with SFR, SSFR, and SFE. We also compare the r31 values for AGN and SFGs. In Section 5, we use the modeling of the line ratio using a PDR (photodissociation region) code to test which parameters regulate the CO line ratios. Finally, in Section 6, we compare the KS relation with molecular gas masses derived using the CO(1–0) and CO(3–2) line emission.

luminosity line ratio in a sample of nearby (z < 0.05) SFGs and AGN. In Sections 2 and 3, we describe the sample and the CO observations. In Section 4, we present the r31 values and analyze the correlation with SFR, SSFR, and SFE. We also compare the r31 values for AGN and SFGs. In Section 5, we use the modeling of the line ratio using a PDR (photodissociation region) code to test which parameters regulate the CO line ratios. Finally, in Section 6, we compare the KS relation with molecular gas masses derived using the CO(1–0) and CO(3–2) line emission.

Throughout this work, we assume a cosmological model with Ωλ = 0.7, ΩM = 0.3 , and H0 = 70 km s−1 Mpc−1.

2. Sample

2.1. Star-forming Galaxies: xCOLD GASS

The xCOLD GASS survey (Saintonge et al. 2011a, 2017) was designed to observe the CO(1–0) emission for ∼500 galaxies in order to establish the first unbiased scaling relations between the cold gas (atomic and molecular) contents of galaxies and their stellar, structural, and chemical properties. A sample of 25 galaxies from xCOLD GASS also has JCMT observations of the CO(3–2) emission line. The sample was selected based on the following criteria:

- 1.Good detection of the CO(1–0) line (signal-to-noise of the line >3).

- 2.CO(3–2) luminosity high enough to require less than two hours of integration time with the JCMT in band 3 (opacity

). Assuming r31 = 0.5, this requirement corresponds to CO(1–0) luminosities

). Assuming r31 = 0.5, this requirement corresponds to CO(1–0) luminosities  K km s−1 pc2.

K km s−1 pc2. - 3.The targets were selected to span a broad range of specific star formation rates (

,

,  ) and SFEs (

) and SFEs ( /

/ ,

,  ).

).

The galaxies in the sample are in the redshift interval 0.026 < z < 0.049. They have stellar masses in the range 10 < log M*/M⊙ < 11 and SFRs in the range ![$-0.05\,\lt \mathrm{logSFR}/[{M}_{\odot }{\mathrm{yr}}^{-1}]\lt 1.54$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/889/2/103/revision1/apjab6221ieqn12.gif) .

.

All the galaxy properties are taken from the xCOLD GASS catalog (Saintonge et al. 2017). In particular, SFRs are calculated by combining the IR- and UV-based SFR components obtained from Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and GALEX photometry, as described in Janowiecki et al. (2017). Stellar masses come from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) DR7 MPA/JHU catalog.11 The 25 galaxies with CO(3–2) observations are not classified as AGN by the optical emission-line diagnostics BPT diagram (Baldwin et al. 1981; Kewley et al. 2001; Kauffmann et al. 2003). Four objects are classified as composite, one as a LINER, and the remaining galaxies are classified as star-forming. The properties of the sample are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Properties of the xCOLD GASS Sample

| Index | R.A. | Decl. | z | D25 | log M* | log SFR |

|

log M(H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (deg) | (deg) | (arcsec) | (log  ) ) |

(log  yr−1) yr−1) |

|

(log  ) ) |

||

| 522 | 171.07767 | 0.64373 | 0.02637 | 51.7 | 10.08 | 0.40 | 4.35 | 9.13 |

| 1115 | 214.56213 | 0.89111 | 0.02595 | 69.3 | 10.11 | 0.76 | 4.35 | 9.61 |

| 1137 | 215.81121 | 0.97835 | 0.04007 | 38.8 | 10.28 | 0.56 | 4.35 | 9.42 |

| 1221 | 218.85558 | 0.33433 | 0.03455 | 23.4 | 10.20 | 0.84 | 4.35 | 9.73 |

| 3819 | 25.42996 | 13.67579 | 0.04531 | 27.7 | 10.67 | 1.03 | 4.35 | 9.98 |

| 3962 | 30.99646 | 14.31038 | 0.04274 | 46.3 | 10.90 | 0.80 | 4.35 | 10.06 |

| 4045 | 32.88983 | 13.91716 | 0.02651 | 43.5 | 10.47 | 0.66 | 4.35 | 9.71 |

| 7493 | 216.83387 | 2.83838 | 0.02644 | 46.1 | 10.56 | 0.41 | 4.35 | 9.64 |

| 9551 | 216.88492 | 4.82163 | 0.02688 | 60.3 | 10.91 | 0.28 | 4.35 | 9.97 |

| 11112 | 345.66796 | 13.32907 | 0.02765 | 51.6 | 10.81 | 0.46 | 4.35 | 9.85 |

| 11223 | 346.56850 | 13.98231 | 0.03554 | 33.6 | 10.64 | 0.67 | 4.35 | 9.94 |

| 11408 | 350.61417 | 13.81586 | 0.026 | 45.4 | 10.05 | 0.08 | 4.35 | 9.12 |

| 14712 | 139.74192 | 5.88840 | 0.03827 | 35.5 | 10.55 | 0.63 | 4.35 | 9.82 |

| 15155 | 160.22996 | 5.99141 | 0.02773 | 79.6 | 10.19 | 0.57 | 4.35 | 9.88 |

| 22436 | 139.97725 | 32.93328 | 0.04916 | 58.8 | 10.42 | 1.54 | 1.00 | 9.75 |

| 23194 | 158.38929 | 11.87138 | 0.03404 | 41.0 | 10.59 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 9.22 |

| 23245 | 160.91283 | 12.06066 | 0.02623 | 42.9 | 10.11 | −0.05 | 4.35 | 8.76 |

| 24973 | 218.82654 | 35.11868 | 0.0285 | 47.5 | 10.61 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 9.33 |

| 25327 | 203.10100 | 11.10636 | 0.03144 | 41.6 | 10.03 | 1.40 | 1.00 | 9.72 |

| 25763 | 135.79688 | 10.15197 | 0.02962 | 54.0 | 10.11 | 0.22 | 4.35 | 9.39 |

| 26221 | 154.15996 | 12.57738 | 0.03166 | 75.5 | 10.98 | 0.57 | 4.35 | 10.07 |

| 28365 | 235.34412 | 28.22975 | 0.03209 | 56.1 | 10.36 | 0.60 | 4.35 | 9.65 |

| 40439 | 196.06267 | 9.22346 | 0.03501 | 70.8 | 10.95 | 0.73 | 4.35 | 9.89 |

| 42013 | 229.01862 | 6.84763 | 0.03681 | 39.7 | 10.77 | 0.70 | 4.35 | 9.96 |

| 48369 | 167.80421 | 28.71190 | 0.02931 | 20.2 | 10.32 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 9.42 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

2.2. Active Galactic Nuclei: BASS

We include in our study a sample of AGN selected in the hard X-ray from the Swift/BAT 70 Month survey (Baumgartner et al. 2013). We have CO(3–2) observations of 46 BAT AGN at redshift <0.04. In our analysis, we focus on sources for which we also have observations of the CO(2–1) transition. Additionally, we discard from our sample three AGN for which Herschel FIR observations are not available and thus we cannot infer their SFR. Thus, the final BASS sample that we use in our analysis consists of 36 objects. These sources are part of the BAT AGN Spectroscopic Survey (BASS12 ), for which ancillary information from optical and X-ray spectroscopic analysis is available (Koss et al. 2017; Ricci et al. 2017). The AGN are in the redshift range 0.002 < z < 0.040.

The SFR is inferred from the total (8–1000 μm) infrared (IR) luminosity due to star formation given in Shimizu et al. (2017), which was measured by decomposing the IR spectral energy distribution (SED) in the AGN and host galaxy component. We use the following conversion from total IR luminosity (3–1100 μm range) to SFR, calculated assuming a Kroupa IMF (Hao et al. 2011; Murphy et al. 2011; Kennicutt & Evans 2012):

where the SFR is in units of M⊙ yr−1 and LIR is the total IR luminosity in erg s−1.

We use stellar masses measured for BAT AGN host galaxies from N. Secrest et al. (2020, in preparation). They are derived by spectrally deconvolving the AGN emission from stellar emission via SED decomposition, combining near-IR data from the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS), which is more sensitive to stellar emission, with mid-IR data from the AllWISE catalog (Wright et al. 2010), which is more sensitive to AGN emission. The galaxies in the sample have stellar masses in the range  and SFR in the range

and SFR in the range ![$-0.83\lt \mathrm{logSFR}/[{M}_{\odot }{\mathrm{yr}}^{-1}]\lt 1.75$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/889/2/103/revision1/apjab6221ieqn19.gif) . Table 2 lists the properties of this sample.

. Table 2 lists the properties of this sample.

Table 2. Properties of the BASS Sample

| BAT | Name | R.A. | Decl. | z | Rk20 | log M* | log SFR |

|

log M(H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | (deg) | (deg) | (arcsec) | (log  ) ) |

(log  yr−1) yr−1) |

|

(log  ) ) |

||

| 144 | NGC 1068 | 40.66960 | −0.01330 | 0.00303 | 95.0 | 10.54 | ⋯ | 4.35 | 9.79 |

| 173 | NGC 1275 | 49.95070 | 41.51170 | 0.01658 | 62.9 | 11.13 | ⋯ | 4.35 | ⋯ |

| 228 | Mrk 618 | 69.09300 | −10.37600 | 0.03464 | 18.1 | 10.62 | 1.19 | 4.35 | 10.19 |

| 308 | NGC 2110 | 88.04740 | −7.45620 | 0.00739 | 54.9 | 10.56 | 0.15 | 4.35 | 8.62 |

| 310 | MCG +08-11-011 | 88.72340 | 46.43930 | 0.02019 | 54.8 | 10.72 | −0.43 | 4.35 | 9.84 |

| 316 | IRAS 05589 + 2828 | 90.54365 | 28.47205 | 0.03309 | 0.0 | 10.57 | 0.35 | 4.35 | 9.75 |

| 337 | VIIZW 073 | 98.19654 | 63.67367 | 0.04042 | 34.3 | 10.46 | 1.13 | 4.35 | 9.98 |

| 382 | Mrk 79 | 115.63670 | 49.80970 | 0.02213 | 30.9 | 10.49 | 0.46 | 4.35 | ⋯ |

| 399 | 2MASX J07595347 + 2323241 | 119.97280 | 23.39010 | 0.02894 | 21.1 | 10.72 | ⋯ | 4.35 | 10.32 |

| 400 | IC 0486 | 120.08740 | 26.61350 | 0.02656 | 19.9 | 10.57 | 0.49 | 4.35 | 9.75 |

| 404 | Mrk 1210 | 121.02440 | 5.11380 | 0.01354 | 15.2 | 9.93 | −0.18 | 4.35 | ⋯ |

| 405 | MCG +02-21-013 | 121.19330 | 10.77670 | 0.03486 | 19.6 | 10.76 | 0.33 | 4.35 | 10.28 |

| 439 | Mrk 18 | 135.49300 | 60.15200 | 0.01101 | 18.0 | 9.74 | 0.01 | 4.35 | 8.73 |

| 451 | IC 2461 | 139.99200 | 37.19100 | 0.00753 | 40.5 | 10.06 | −0.45 | 4.35 | 9.20 |

| 471 | NGC 2992 | 146.42520 | −14.32640 | 0.00757 | 50.9 | 10.22 | 0.34 | 4.35 | 9.30 |

| 480 | NGC 3081 | 149.87310 | −22.82630 | 0.00763 | 54.3 | 9.96 | −0.33 | 4.35 | 8.85 |

| 497 | NGC 3227 | 155.87740 | 19.86510 | 0.00329 | 92.6 | 10.06 | 0.35 | 4.35 | 9.74 |

| 517 | UGC 05881 | 161.67700 | 25.93130 | 0.02048 | 14.5 | 10.17 | 0.42 | 4.35 | 9.42 |

| 530 | NGC 3516 | 166.69790 | 72.56860 | 0.00871 | 40.8 | 10.65 | −0.28 | 4.35 | 8.73 |

| 532 | IC 2637 | 168.45700 | 9.58600 | 0.02915 | 18.1 | 10.60 | 1.04 | 4.35 | 10.10 |

| 548 | NGC 3718 | 173.14520 | 53.06790 | 0.00279 | 75.5 | 10.03 | −0.83 | 4.35 | 8.49 |

| 552 | Mrk 739E | 174.12200 | 21.59600 | 0.02945 | 20.4 | 10.60 | 0.89 | 4.35 | 9.98 |

| 560 | NGC 3786 | 174.92700 | 31.90900 | 0.00897 | 49.0 | 10.32 | −0.06 | 4.35 | 9.52 |

| 585 | NGC 4051 | 180.79010 | 44.53130 | 0.00203 | 102.6 | 9.82 | 0.17 | 4.35 | 9.80 |

| 588 | UGC 07064 | 181.18060 | 31.17730 | 0.02508 | 21.9 | 10.60 | 0.76 | 4.35 | 10.10 |

| 590 | NGC 4102 | 181.59630 | 52.71090 | 0.00185 | 68.6 | 10.18 | 0.54 | 4.35 | 9.57 |

| 599 | NGC 4180 | 183.26200 | 7.03800 | 0.00700 | 40.0 | 9.96 | 0.17 | 4.35 | ⋯ |

| 608 | Mrk 766 | 184.61050 | 29.81290 | 0.01292 | 25.6 | 10.11 | 0.35 | 4.35 | 9.26 |

| 609 | M106 | 184.73960 | 47.30400 | 0.00168 | 263.9 | 10.22 | −0.10 | 4.35 | 9.29 |

| 615 | NGC 4388 | 186.44480 | 12.66210 | 0.00834 | 92.9 | 10.08 | −0.09 | 4.35 | 7.91 |

| 631 | NGC 4593 | 189.91430 | −5.34430 | 0.00835 | 80.6 | 10.46 | ⋯ | 4.35 | 9.24 |

| 669 | NGC 5100NED02 | 200.24830 | 8.97830 | 0.03259 | 21.9 | 10.71 | 1.19 | 4.35 | ⋯ |

| 670 | MCG -03-34-064 | 200.60190 | −16.72860 | 0.01682 | 25.3 | 10.47 | 0.68 | 4.35 | 9.34 |

| 688 | NGC 5290 | 206.32990 | 41.71260 | 0.00854 | 89.0 | 10.39 | −0.03 | 4.35 | 9.86 |

| 703 | Mrk 463 | 209.01200 | 18.37210 | 0.05015 | 14.0 | 10.59 | ⋯ | 4.35 | ⋯ |

| 712 | NGC 5506 | 213.31190 | −3.20750 | 0.00609 | 74.6 | 9.92 | −0.26 | 4.35 | 8.84 |

| 723 | NGC 5610 | 216.09540 | 24.61440 | 0.01691 | 39.4 | 10.34 | 0.70 | 4.35 | 9.91 |

| 739 | NGC 5728 | 220.59970 | −17.25320 | 0.00990 | 80.4 | 10.31 | 0.19 | 4.35 | 9.34 |

| 766 | NGC 5899 | 228.76350 | 42.04990 | 0.00844 | 67.8 | 10.37 | 0.54 | 4.35 | 9.74 |

| 772 | MCG -01-40-001 | 233.33630 | −8.70050 | 0.02285 | 43.7 | 10.57 | 0.81 | 4.35 | 9.84 |

| 783 | NGC 5995 | 237.10400 | −13.75780 | 0.02442 | 24.3 | 10.87 | 1.04 | 4.35 | 10.18 |

| 841 | NGC 6240 | 253.24540 | 2.40090 | 0.02386 | 39.9 | 11.02 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 10.07 |

| 1042 | 2MASX J19373299–0613046 | 294.38800 | −6.21800 | 0.01036 | 19.8 | 9.97 | −0.17 | 4.35 | 9.29 |

| 1046 | NGC 6814 | 295.66940 | −10.32350 | 0.00576 | 71.7 | 10.32 | 0.14 | 4.35 | 9.16 |

| 1133 | Mrk 520 | 330.17242 | 10.55221 | 0.02753 | 14.4 | 10.33 | ⋯ | 4.35 | ⋯ |

| 1184 | NGC 7479 | 346.23610 | 12.32290 | 0.00705 | 87.9 | 10.41 | 0.57 | 4.35 | 9.86 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

2.3. Infrared-luminous Galaxies: SLUGS

We also include in our analysis a sample of IR-luminous galaxies ( ) from the SCUBA Local Universe Galaxy Survey (SLUGS; Dunne et al. 2000). We include this sample in order to extend the parameter range to galaxies with higher SFRs. We chose this sample over other samples available in the literature because it has beam-matched observations and information about how to scale the total SFR to the SFR within the beam.

) from the SCUBA Local Universe Galaxy Survey (SLUGS; Dunne et al. 2000). We include this sample in order to extend the parameter range to galaxies with higher SFRs. We chose this sample over other samples available in the literature because it has beam-matched observations and information about how to scale the total SFR to the SFR within the beam.

We select the 38 SLUGS galaxies with observations of both CO(3–2) and CO(1–0) available in Yao et al. (2003). These galaxies are in the redshift range 0.006 < z < 0.048. Stellar masses from the SDSS DR7 MPA/JHU catalog are available for only 22 galaxies of this sample and are in the range  .

.

We use the optical emission-line diagnostic (Baldwin et al. 1981; Kewley et al. 2001; Kauffmann et al. 2003) from SDSS DR12 to distinguish between AGN and SFGs. Of the 22 galaxies with stellar masses from SDSS, two are classified as Seyferts (IRAS 10173+0828 and Arp 220), seven as Composite, and 13 as SFGs. We include the galaxies classified as Composite in the SFG sample.

The total SFRs are derived from the total IR luminosities LIR using Equation (1). We measure LIR by integrating the SED, approximated by a modified blackbody (MBB), in the range 8–1000 μm. The parameters of the MBB model are given in Dunne et al. (2000). We calculate the uncertainties on LIR by propagating the uncertainties on the MBB parameters given in Dunne et al. (2000). The SFRs are in the range 0.18 < log SFR/[ yr−1] < 2.15. Yao et al. (2003) also provide the FIR luminosity and SFR corresponding to the 15'' central part of the galaxy (equivalent to the size of the CO beam), obtained by applying a scale factor to the total FIR luminosity. This factor is derived from the original 850 μm SCUBA-2 images. To calculate the SFE, we use the SFR in the 15'' central part of the galaxy, as it matches the beam size of the CO observations.

yr−1] < 2.15. Yao et al. (2003) also provide the FIR luminosity and SFR corresponding to the 15'' central part of the galaxy (equivalent to the size of the CO beam), obtained by applying a scale factor to the total FIR luminosity. This factor is derived from the original 850 μm SCUBA-2 images. To calculate the SFE, we use the SFR in the 15'' central part of the galaxy, as it matches the beam size of the CO observations.

We note that for this sample the molecular gas mass  , and consequently also the SFE, represents only the value in the central 15'' region of the galaxy, as no correction has been applied to extrapolate from the beam area to the total

, and consequently also the SFE, represents only the value in the central 15'' region of the galaxy, as no correction has been applied to extrapolate from the beam area to the total  .

.

2.4. Samples in the SFR–M* Plane

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the xCOLD GASS, BASS, and SLUGS samples in the SFR–M* plane. The position of the star formation main sequence (Saintonge et al. 2016) is shown by the dashed line, and the dotted lines show the 0.4 dex dispersion. The "full xCOLD GASS" sample is shown by the gray points for reference. The three samples cover a similar range in stellar masses. All galaxies from the xCOLD GASS sample are on the main sequence or above, while the IR-luminous galaxies from the SLUGs sample are mostly above the main sequence. The BASS sample spans a broad range of specific star formation rate (SSFR), with ∼8 AGN below the main sequence and the rest of the sample overlapping in the parameter space with the xCOLD GASS galaxies. The right panel of Figure 1 shows the SSFR versus the SFE. The three samples span a similar range of SSFRs (−11 < log SSFR/[yr−1] < −8.5). The galaxies of the xCOLD GASS sample have slightly higher SFEs than the BASS galaxies at the same SSFR, but there is a good overlap with the BASS sample. The IR-luminous galaxies from SLUGS have in general high SSFR and high SFE.

Figure 1. Left: distribution of the xCOLD GASS, BASS, and SLUGS samples in the SFR–M* plane. The position of the star formation main sequence (Saintonge et al. 2016) is shown by the dashed line; the 0.4 dex dispersion is shown by dotted lines. The full xCOLD GASS sample is shown by the gray points, while the subsample with CO(3–2) observations is shown in magenta. Right: SSFR vs. star SFE (SFE = SFR/ ). Galaxies from the BASS sample have in general lower SFE than the xCOLD GASS galaxies at the same SSFR. For the SLUGS sample, we plot only the galaxies with angular diameter D < 100'', as their SFE is measured within the beam, while the SSFR is the total value.

). Galaxies from the BASS sample have in general lower SFE than the xCOLD GASS galaxies at the same SSFR. For the SLUGS sample, we plot only the galaxies with angular diameter D < 100'', as their SFE is measured within the beam, while the SSFR is the total value.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image3. CO Data, Observations, and Data Reduction

3.1. xCOLD GASS

3.1.1. xCOLD GASS: CO(1–0) Data from the Literature

The CO(1–0) line luminosities  are taken from the xCOLD GASS catalog (Saintonge et al. 2017). The CO(1–0) line fluxes are observed with the IRAM 30 m telescope (beam size: 22''). The 25 galaxies from xCOLD GASS selected for the CO(3–2) observations all have signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) > 3 in CO(1–0). We refer to Saintonge et al. (2017) for information about the observations and data reduction.

are taken from the xCOLD GASS catalog (Saintonge et al. 2017). The CO(1–0) line fluxes are observed with the IRAM 30 m telescope (beam size: 22''). The 25 galaxies from xCOLD GASS selected for the CO(3–2) observations all have signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) > 3 in CO(1–0). We refer to Saintonge et al. (2017) for information about the observations and data reduction.

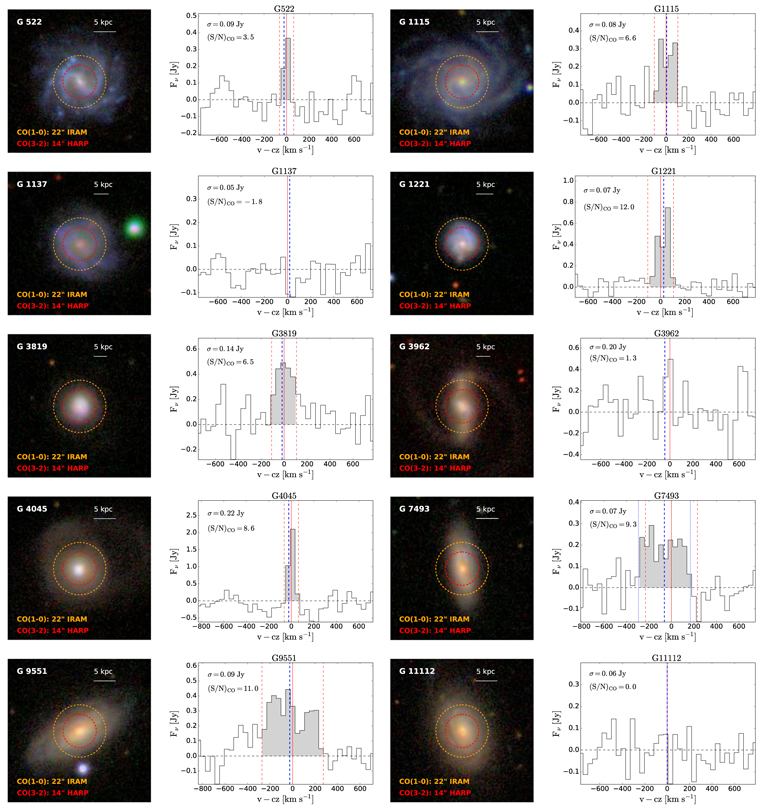

3.1.2. xCOLD GASS: CO(3–2) Observations

The CO(3–2) observations are taken with the HARP instrument (Heterodyne Array Receiver Program, beam size: 14''; Buckle et al. 2009) on the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT; observing program M14AU21, PI: A. Saintonge). These observations took place between January and June 2014. Each CO(3–2) spectrum was observed in a single HARP pointing in "hybrid" mode, which produces two spectra for every scan (in two spectral windows). The spectra were reduced using the Starlink software (Currie et al. 2014). First, the two spectra within each scan were combined, after correcting for any baseline difference, and then all scans were combined together. A linear fit to the continuum was used to remove the baseline and then the spectrum was binned to a resolution of 40 km s−1.

The HARP instrument has 4 × 4 receptors (pixels), each one with a half-power beam width of 14''. We extract the CO(3–2) spectrum only from the pixel that is centered on the galaxy. The technique used to measure the flux from the reduced spectrum is the same used for the main xCOLD GASS survey (Saintonge et al. 2017). We convert the antenna temperature to flux units by applying the point source sensitivity factor 30 Jy K−1 recommended for HARP.13 We measure the velocity-integrated line flux SCO in Jy km s−1 by adding the signal within a spectral window. We initially set the width of the spectral window (WCO) equal to the FWHM of the CO(1–0) given in the xCOLD GASS catalog. In case the CO(3–2) line is clearly wider, we extend WCO to cover the total line emission. We determine the center of the line based on the SDSS spectroscopic redshift. In two cases where the CO(3–2) is clearly shifted with respect to the position determined from the SDSS redshift, we use the redshift of the CO(1–0) line, which is shifted in the same direction as the CO(3–2) line, to center the CO(3–2) line. We measure the baseline rms noise of the line-free channels (σCO) per 40 km s−1 channel in the spectral regions around the CO line.

The beam-integrated CO(3–2) line luminosity in units of K km s−1 pc2 is defined following Solomon et al. (1997) as

where  is the velocity-integrated CO(3–2) line flux within the HARP beam in units of Jy km s−1, νobs is the observed frequency of the CO(3–2) line in GHz, and DL is the luminosity distance in Mpc. The error on the line flux is defined as

is the velocity-integrated CO(3–2) line flux within the HARP beam in units of Jy km s−1, νobs is the observed frequency of the CO(3–2) line in GHz, and DL is the luminosity distance in Mpc. The error on the line flux is defined as

where σCO is the rms noise achieved around the CO(3–2) line in spectral channels with width Δwch = 40 km s−1 and WCO the width (in km s−1) of the spectral window where we integrate the CO(3–2) line flux.

We use a detection threshold of S/N > 3, defined as S/N  , which is the same adopted for the main xCOLD GASS catalog. In 7 of 25 galaxies, the CO(3–2) line is not detected and we use conservative upper limits equal to five times the error:

, which is the same adopted for the main xCOLD GASS catalog. In 7 of 25 galaxies, the CO(3–2) line is not detected and we use conservative upper limits equal to five times the error:  . The 5σ upper limits correspond to a "false negative" fraction of 2%, which is the probability that a source with "true" flux higher than this upper limit is not detected. To calculate

. The 5σ upper limits correspond to a "false negative" fraction of 2%, which is the probability that a source with "true" flux higher than this upper limit is not detected. To calculate  we use the FWHM of the CO(1–0) line as an approximation for the width of the CO(3–2) line (

we use the FWHM of the CO(1–0) line as an approximation for the width of the CO(3–2) line ( ). All of the CO(3–2) spectra from xCOLD GASS are shown in the Appendix (Figure 8) and the measured line properties in Table 3.

). All of the CO(3–2) spectra from xCOLD GASS are shown in the Appendix (Figure 8) and the measured line properties in Table 3.

Table 3. CO(3–2) Measurements for the xCOLD GASS Sample

| Index |

rms rms |

S/N

|

flag

|

|

|

|

r31 | Beam Corr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mK) | (Jy km s−1) | (log K km s−1 pc2) | (log K km s−1 pc2) | 14'' to 22'' | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

| 522 | 3.00 | 3.47 | 1 | 22.63 ± 3.67 | 7.90 ± 0.13 | 8.34 ± 0.07 | 0.54 ± 0.18 | 1.48 |

| 1115 | 2.73 | 6.62 | 1 | 50.81 ± 8.24 | 8.24 ± 0.07 | 8.75 ± 0.07 | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 1.41 |

| 1137 | 1.80 | −1.83 | 2 | −7.37 ± 3.58 | <8.10 | 8.72 ± 0.05 | <0.31 | 1.28 |

| 1221 | 2.22 | 12.03 | 1 | 76.36 ± 8.69 | 8.67 ± 0.04 | 9.04 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 1.18 |

| 3819 | 4.56 | 6.53 | 1 | 86.85 ± 9.42 | 8.96 ± 0.07 | 9.30 ± 0.04 | 0.52 ± 0.10 | 1.15 |

| 3962 | 6.52 | 1.33 | 2 | 29.70 ± 11.12 | <9.01 | 9.35 ± 0.04 | <0.55 | 1.19 |

| 4045 | 7.50 | 8.56 | 1 | 139.84 ± 13.38 | 8.70 ± 0.05 | 9.03 ± 0.04 | 0.53 ± 0.08 | 1.15 |

| 7493 | 2.24 | 9.32 | 1 | 87.24 ± 12.32 | 8.49 ± 0.05 | 8.93 ± 0.05 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 1.23 |

| 9551 | 3.06 | 10.97 | 1 | 152.23 ± 22.25 | 8.75 ± 0.04 | 9.25 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 1.27 |

| 11112 | 2.07 | 0.04 | 2 | 0.38 ± 16.14 | <8.19 | 9.11 ± 0.05 | <0.16 | 1.36 |

| 11223 | 3.24 | 8.65 | 1 | 118.99 ± 12.47 | 8.88 ± 0.05 | 9.24 ± 0.04 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 1.17 |

| 11408 | 3.99 | −0.09 | 2 | −0.79 ± 3.63 | <7.98 | 8.36 ± 0.06 | <0.60 | 1.44 |

| 14712 | 3.87 | −0.38 | 2 | −4.21 ± 8.72 | <8.53 | 9.12 ± 0.04 | <0.34 | 1.33 |

| 15155 | 1.14 | 16.03 | 1 | 76.42 ± 14.23 | 8.47 ± 0.03 | 9.07 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 1.35 |

| 22436 | 2.88 | 16.83 | 1 | 277.51 ± 16.61 | 9.54 ± 0.03 | 9.64 ± 0.05 | 0.97 ± 0.12 | 1.24 |

| 23194 | 4.32 | 12.70 | 1 | 209.96 ± 11.39 | 9.09 ± 0.03 | 9.15 ± 0.05 | 1.15 ± 0.15 | 1.30 |

| 23245 | 3.68 | 2.18 | 2 | 17.48 ± 2.17 | <7.79 | 8.05 ± 0.06 | <0.84 | 1.53 |

| 24973 | 8.11 | 12.31 | 1 | 218.30 ± 18.02 | 8.95 ± 0.04 | 9.22 ± 0.05 | 0.71 ± 0.09 | 1.32 |

| 25327 | 7.48 | 23.79 | 1 | 677.88 ± 43.03 | 9.53 ± 0.02 | 9.69 ± 0.04 | 0.79 ± 0.08 | 1.14 |

| 25763 | 5.56 | −0.15 | 2 | −1.77 ± 4.66 | <8.31 | 8.57 ± 0.07 | <0.75 | 1.36 |

| 26221 | 3.17 | 12.09 | 1 | 161.63 ± 17.63 | 8.91 ± 0.04 | 9.30 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ± 0.07 | 1.31 |

| 28365 | 3.22 | 4.65 | 1 | 33.01 ± 7.23 | 8.24 ± 0.09 | 8.89 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | 1.49 |

| 40439 | 1.92 | 3.15 | 1 | 20.48 ± 7.69 | 8.11 ± 0.14 | 8.96 ± 0.08 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 1.80 |

| 42013 | 3.81 | 6.81 | 1 | 100.05 ± 13.38 | 8.84 ± 0.06 | 9.27 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.08 | 1.16 |

| 48369 | 3.99 | 18.72 | 1 | 283.35 ± 26.96 | 9.09 ± 0.02 | 9.41 ± 0.04 | 0.52 ± 0.05 | 1.08 |

Note. (1) Index. (2) Standard deviation of the noise. (3) Integrated S/N of the CO(3–2) line. (4) Flag for the detection of the CO(3–2) line based on a peak S/N > 3. 1: Detected, 2: non-detected. (5) Velocity-integrated flux  within the 14'' JCMT HARP beam. (6) CO(3–2) luminosity within the 14'' JCMT HARP beam. (7) CO(1–0) luminosity within the 22'' IRAM beam. (8) Beam-corrected luminosity ratio

within the 14'' JCMT HARP beam. (6) CO(3–2) luminosity within the 14'' JCMT HARP beam. (7) CO(1–0) luminosity within the 22'' IRAM beam. (8) Beam-corrected luminosity ratio  . (9) Beam-correction factor for extrapolating the CO(3–2) flux from the 14'' JCMT HARP to the 22'' IRAM beam.

. (9) Beam-correction factor for extrapolating the CO(3–2) flux from the 14'' JCMT HARP to the 22'' IRAM beam.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

3.2. BASS

Both the CO(2–1) and CO(3–2) lines have been observed at the JCMT: the CO(3–2) with HARP and the CO(2–1) with the RxA instrument (beam size: 20''). The HARP observations took place in weather bands 3–4 (corresponding to an opacity  ), while the RxA observations took place in weather band 5 (

), while the RxA observations took place in weather band 5 ( ). The observations and data reduction of the CO(2–1) line emission are explained in detail in M. Koss et al. (2020, in preparation).

). The observations and data reduction of the CO(2–1) line emission are explained in detail in M. Koss et al. (2020, in preparation).

The CO(3–2) observations were taken between 2011 February and 2012 November in programs M11AH42C (PI: E. Treister) and M12BH03E (PI: M. Koss). Additionally, we also include 13 spectra from archival observations. Each galaxy was initially observed for 30 minutes. For weak detections, additional observations were obtained up to no more than two hours. The individual scans for a single galaxy were first-order baseline-subtracted and then coadded. We extract the CO(3–2) spectrum only from the pixel centered on the galaxy. We measure the CO(3–2) and CO(2–1) line fluxes using the same method as for the xCOLD GASS sample, for consistency. We measure the  line flux in Jy km s−1 by adding the signal within a spectral range that covers the entire width of the line. In the Appendix, we show the CO(3–2) spectra from BASS, in which we highlight the spectral regions where we integrate the fluxes. All BASS objects have good detections (i.e., S/N > 3) of the CO(2–1) lines, while we have non-detections (i.e., S/N < 3) in the CO(3–2) line for 3 of 36 galaxies. For these galaxies, we use upper limits equal to five times the flux error:

line flux in Jy km s−1 by adding the signal within a spectral range that covers the entire width of the line. In the Appendix, we show the CO(3–2) spectra from BASS, in which we highlight the spectral regions where we integrate the fluxes. All BASS objects have good detections (i.e., S/N > 3) of the CO(2–1) lines, while we have non-detections (i.e., S/N < 3) in the CO(3–2) line for 3 of 36 galaxies. For these galaxies, we use upper limits equal to five times the flux error:  .

.

Our set of observations is not homogeneous because for the xCOLD GASS and SLUGS samples, we compare the CO(3–2) to the CO(1–0) line, but for the BASS sample, we have to estimate CO(1–0) from the CO(2–1) line. Therefore, we need to assume a value for the ratio  . The typical value observed for normal spiral galaxies is r21 = 0.8 (Leroy et al. 2009; Saintonge et al. 2017). Leroy et al. (2009) studied a sample of 10 nearby spiral galaxies and found r21 values between 0.48 and 1.06, with most values in the range 0.6–1.0. They found an average of 0.81. For the xCOLD GASS survey, Saintonge et al. (2017) found a mean value of r21 = 0.79 ± 0.03 using a sample of 28 galaxies.

. The typical value observed for normal spiral galaxies is r21 = 0.8 (Leroy et al. 2009; Saintonge et al. 2017). Leroy et al. (2009) studied a sample of 10 nearby spiral galaxies and found r21 values between 0.48 and 1.06, with most values in the range 0.6–1.0. They found an average of 0.81. For the xCOLD GASS survey, Saintonge et al. (2017) found a mean value of r21 = 0.79 ± 0.03 using a sample of 28 galaxies.

Some of the AGN in our sample (12/36) have recently been observed with the IRAM 30 m telescope as part of a program to measure CO(1–0) line luminosity for 133 BAT AGN (PI: T. Shimizu). We compute the r21 line ratios for these 12 objects using the values from T. T. Shimizu et al. (2020, in preparation). Because the difference in beam size is very small (IRAM: 22'', JCMT RxA: 20''), we did not apply any beam corrections. The r21 line ratios for these 12 objects are in the range 0.4–2.1, with a median r21 = 0.72. We obtain a robust standard deviation by computing the median absolute deviation MAD = 0.17. The robust standard deviation, under the assumption of a normal distribution, is given by  (Hoaglin et al. 1983). For the 12 objects with CO(1–0) observations, we use the CO(1–0) luminosities from T. T. Shimizu et al. (2020, in preparation) to compute the r31 line ratio. For the remaining AGN, we use a constant r21 = 0.72, and we assume an uncertainty of 0.26 on this value. The CO line fluxes for this sample are shown in Table 4.

(Hoaglin et al. 1983). For the 12 objects with CO(1–0) observations, we use the CO(1–0) luminosities from T. T. Shimizu et al. (2020, in preparation) to compute the r31 line ratio. For the remaining AGN, we use a constant r21 = 0.72, and we assume an uncertainty of 0.26 on this value. The CO line fluxes for this sample are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. CO(3–2) and CO(2–1) Measurements for the BASS Sample

| BAT | S/N | Flag |

|

|

|

r31 | Beam Corr. | Beam Corr. Tot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | CO(32) | CO(32) | (Jy km s−1) | (log K km s−1 pc2) | (log K km s−1 pc2) | 14'' to 20'' | 20'' to Total | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

| 144 | 87.30 | 1 | 2787.72 ± 251.40 | 8.08 ± 0.00 | 8.49 ± 0.00 | 0.61 ± 0.00 | 1.95* | 3.62* |

| 173 | 24.65 | 1 | 198.29 ± 21.54 | 8.44 ± 0.02 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.80* | 2.32* |

| 228 | 13.39 | 1 | 159.38 ± 40.79 | 8.99 ± 0.03 | 9.26 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.13 | 1.13 | 1.54 |

| 308 | 23.52 | 1 | 132.00 ± 11.37 | 7.65 ± 0.02 | 7.65 ± 0.02 | 1.01 ± 0.26 | 1.25 | 1.73 |

| 310 | 12.13 | 1 | 72.27 ± 10.06 | 8.17 ± 0.04 | 8.32 ± 0.11 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 1.31 | 4.33 |

| 316 | 3.83 | 1 | 62.35 ± 10.48 | 8.54 ± 0.11 | 8.76 ± 0.00 | 0.54 ± 0.20 | 1.14 | 1.80 |

| 337 | −0.97 | 2 | −25.80 ± 40.08 | <9.04 | 8.86 ± 0.10 | <0.92 | 1.14 | 1.63 |

| 382 | 7.05 | 1 | 51.22 ± 9.23 | 8.10 ± 0.06 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.31 | 2.50 |

| 399 | 7.70 | 1 | 153.57 ± 18.33 | 8.81 ± 0.06 | 9.20 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 1.16* | 1.61* |

| 400 | 2.09 | 2 | 31.28 ± 21.74 | <8.43 | 9.09 ± 0.08 | <0.53 | 1.17 | 2.21 |

| 404 | 8.81 | 1 | 49.19 ± 12.64 | 7.66 ± 0.05 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.09 | 1.92 |

| 405 | 5.08 | 1 | 72.40 ± 19.39 | 8.65 ± 0.09 | 8.81 ± 0.12 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 1.14 | 1.91 |

| 439 | 10.14 | 1 | 88.24 ± 13.24 | 7.73 ± 0.04 | 7.80 ± 0.10 | 0.69 ± 0.10 | 1.08 | 1.46 |

| 451 | 6.49 | 1 | 47.50 ± 10.23 | 7.58 ± 0.07 | 8.09 ± 0.06 | 0.33 ± 0.11 | 1.33 | 2.34 |

| 471 | 48.97 | 1 | 469.43 ± 34.53 | 8.10 ± 0.01 | 8.33 ± 0.01 | 0.59 ± 0.15 | 1.27 | 1.69 |

| 480 | 13.18 | 1 | 71.51 ± 11.22 | 7.13 ± 0.03 | 7.64 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 1.28 | 2.94 |

| 497 | 32.63 | 1 | 700.29 ± 52.40 | 7.82 ± 0.01 | 8.33 ± 0.00 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | 1.33 | 4.71 |

| 517 | 2.69 | 2 | 27.21 ± 11.45 | <8.03 | 8.34 ± 0.11 | <0.30 | 1.05 | 1.60 |

| 530 | 4.60 | 1 | 55.56 ± 12.08 | 7.62 ± 0.09 | 7.72 ± 0.12 | 0.75 ± 0.32 | 1.19 | 1.88 |

| 532 | 13.95 | 1 | 354.36 ± 30.97 | 9.18 ± 0.03 | 9.34 ± 0.02 | 0.91 ± 0.07 | 1.13 | 1.54 |

| 548 | 3.73 | 1 | 63.49 ± 25.16 | 6.70 ± 0.12 | 7.00 ± 0.07 | 0.59 ± 0.24 | 1.48 | 5.77 |

| 552 | 12.19 | 1 | 118.93 ± 33.69 | 8.72 ± 0.04 | 9.07 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 1.16 | 1.75 |

| 560 | 6.33 | 1 | 217.02 ± 36.42 | 8.18 ± 0.07 | 8.57 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.13 | 1.25 | 1.64 |

| 585 | 42.09 | 1 | 539.72 ± 64.87 | 7.50 ± 0.01 | 7.87 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.12 | 1.36 | 15.66 |

| 588 | 19.59 | 1 | 157.45 ± 25.70 | 8.70 ± 0.02 | 9.05 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 1.20 | 1.80 |

| 590 | 123.24 | 1 | 1978.99 ± 126.31 | 8.35 ± 0.00 | 8.56 ± 0.00 | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 1.25 | 1.87 |

| 599 | 13.42 | 1 | 273.82 ± 36.99 | 7.83 ± 0.03 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.31 | 1.99 |

| 608 | 14.83 | 1 | 148.61 ± 24.68 | 8.10 ± 0.03 | 8.26 ± 0.05 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 1.12 | 1.47 |

| 609 | 29.31 | 1 | 1166.84 ± 109.02 | 7.25 ± 0.01 | 7.66 ± 0.01 | 0.52 ± 0.13 | 1.67 | 7.88 |

| 615 | 37.34 | 1 | 14.89 ± 1.29 | 6.25 ± 0.01 | 6.58 ± 0.02 | 0.53 ± 0.14 | 1.44 | 3.89 |

| 631 | 21.62 | 1 | 115.15 ± 14.23 | 7.53 ± 0.02 | 8.03 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.00 | 1.89* | 2.99* |

| 669 | 4.00 | 1 | 56.64 ± 19.80 | 8.48 ± 0.11 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.48 | 1.21 |

| 670 | 9.10 | 1 | 61.93 ± 10.29 | 7.95 ± 0.05 | 8.42 ± 0.09 | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 1.13 | 1.50 |

| 688 | 41.19 | 1 | 251.32 ± 46.05 | 7.92 ± 0.01 | 8.44 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.09 | 1.54 | 4.87 |

| 703 | −2.11 | 2 | −26.24 ± 14.73 | <8.90 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.41* | 1.09* |

| 712 | 35.71 | 1 | 295.07 ± 29.45 | 7.66 ± 0.01 | 7.85 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.17 | 1.24 | 1.81 |

| 723 | 41.60 | 1 | 341.24 ± 30.06 | 8.69 ± 0.01 | 8.98 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 1.21 | 1.84 |

| 739 | 50.02 | 1 | 420.76 ± 36.26 | 8.02 ± 0.01 | 8.32 ± 0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.13 | 1.28 | 1.93 |

| 766 | 17.23 | 1 | 131.36 ± 16.03 | 7.71 ± 0.03 | 8.27 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 1.64 | 5.48 |

| 772 | 17.93 | 1 | 167.87 ± 18.64 | 8.65 ± 0.02 | 8.73 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.23 | 1.22 | 2.40 |

| 783 | 32.29 | 1 | 317.22 ± 20.31 | 8.98 ± 0.01 | 9.21 ± 0.02 | 0.55 ± 0.14 | 1.16 | 1.70 |

| 841 | 87.81 | 1 | 2897.27 ± 170.89 | 9.92 ± 0.00 | 9.85 ± 0.01 | 1.22 ± 0.02 | 1.18 | 1.48 |

| 1042 | 23.03 | 1 | 135.31 ± 22.74 | 7.86 ± 0.02 | 8.29 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 1.24 | 1.86 |

| 1046 | 8.78 | 1 | 37.78 ± 8.56 | 6.72 ± 0.05 | 7.51 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 1.73 | 8.32 |

| 1133 | 68.37 | 1 | 494.40 ± 81.07 | 9.28 ± 0.01 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.41* | 1.10* |

| 1184 | 52.72 | 1 | 993.78 ± 131.74 | 8.49 ± 0.01 | 8.65 ± 0.00 | 0.72 ± 0.18 | 1.31 | 2.97 |

Note. (1) BAT index. (2) Integrated S/N of the CO(3–2) line. (3) Flag for the detection of the CO(3–2) line based on a peak S/N > 3. 1: Detected, 2: non-detected. (4) Velocity-integrated flux  within the 14'' JCMT HARP beam. (5) CO(3–2) luminosity within the 14'' JCMT HARP beam. (6) CO(2–1) luminosity within the 20'' JCMT RxA beam. Galaxies which do not have CO(2–1) observations have empty entries (...). (7) Beam-corrected luminosity ratio

within the 14'' JCMT HARP beam. (5) CO(3–2) luminosity within the 14'' JCMT HARP beam. (6) CO(2–1) luminosity within the 20'' JCMT RxA beam. Galaxies which do not have CO(2–1) observations have empty entries (...). (7) Beam-corrected luminosity ratio  . (8) Beam correction factor for extrapolating the CO(3–2) flux from the 14'' to the 22'' beam. The star * indicates that the corrections are derived from simulated galaxy profiles, because the FIR images were not available. (9) Beam-correction factor for extrapolating the CO(2–1) flux from the 20'' beam to the total flux. The star * indicates that the corrections are derived from simulated galaxy profiles, because the FIR images were not available.

. (8) Beam correction factor for extrapolating the CO(3–2) flux from the 14'' to the 22'' beam. The star * indicates that the corrections are derived from simulated galaxy profiles, because the FIR images were not available. (9) Beam-correction factor for extrapolating the CO(2–1) flux from the 20'' beam to the total flux. The star * indicates that the corrections are derived from simulated galaxy profiles, because the FIR images were not available.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

3.3. SLUGS

The CO(1–0) observations were taken with the Nobeyama Radio Observatory (NRO) 45 m telescope (beam size: 14 6) and the CO(3–2) observations with the HARP instrument on the JCMT. We take the CO line luminosities and line ratios from Yao et al. (2003), and we refer to that paper for information about the observations and data reduction.

6) and the CO(3–2) observations with the HARP instrument on the JCMT. We take the CO line luminosities and line ratios from Yao et al. (2003), and we refer to that paper for information about the observations and data reduction.

3.4. Beam Corrections

We calculate beam corrections for two purposes: (1) to correct for the different beam sizes of the CO(3–2), CO(2–1), and CO(1–0) observations and (2) to extrapolate the CO luminosity measured within the beam to the total CO luminosity of the galaxy.

(1) Corrections for the different beam sizes:

For the SLUGs sample, the beam sizes are similar (14 6 for the CO(1–0) line and 14'' for the CO(3–2) line); therefore, the line luminosities can be directly compared without applying any corrections for the beam size. For the xCOLD GASS and BASS samples instead, the beam sizes of the telescopes used for the CO(3–2), CO(2–1), and CO(1–0) observations vary between 14'' and 22'', thus we need to apply beam corrections. In order to compare the CO emission from different lines, we need first to ensure that we are comparing fluxes coming from the same part of the galaxy. To estimate the amount of flux that is missing in the observation done with the smaller beam, we use the following approach, which is based on the assumption that the dust emission in the IR is a good tracer of the cold molecular gas distribution (e.g., Leroy et al. 2008). Under this assumption, we can estimate the flux that would be observed from beams of different sizes by measuring the flux within different apertures in the IR images. After that, we apply an additional correction to take into account the fact that the IR images have a point-spread function (PSF) that causes the observed flux to appear more extended than the intrinsic emission.

6 for the CO(1–0) line and 14'' for the CO(3–2) line); therefore, the line luminosities can be directly compared without applying any corrections for the beam size. For the xCOLD GASS and BASS samples instead, the beam sizes of the telescopes used for the CO(3–2), CO(2–1), and CO(1–0) observations vary between 14'' and 22'', thus we need to apply beam corrections. In order to compare the CO emission from different lines, we need first to ensure that we are comparing fluxes coming from the same part of the galaxy. To estimate the amount of flux that is missing in the observation done with the smaller beam, we use the following approach, which is based on the assumption that the dust emission in the IR is a good tracer of the cold molecular gas distribution (e.g., Leroy et al. 2008). Under this assumption, we can estimate the flux that would be observed from beams of different sizes by measuring the flux within different apertures in the IR images. After that, we apply an additional correction to take into account the fact that the IR images have a point-spread function (PSF) that causes the observed flux to appear more extended than the intrinsic emission.

To calculate the beam corrections from the IR images, we apply the following procedure. We multiply the IR image by a 2D Gaussian centered on the galaxy center and with FWHM equal to the beam size, to mimic the effect of the beam sensitivity of the telescope that took the CO observations. Then, we measure the total flux from the image multiplied by the 2D Gaussian. We repeat this measurement for the two beams, and we take the ratio of the fluxes:

For the xCOLD GASS sample, we use the 22 μm images from the WISE survey. Specifically, we use the coadded images from "unWISE,"14 which have been systematically produced without blurring, retaining the intrinsic resolution of the data (Lang 2014; Meisner et al. 2017). For 36 galaxies in our BASS sample, there are Herschel/PACS observations at 70 and 160 μm available (Meléndez et al. 2014; Shimizu et al. 2017). We decide to use the PACS 160 μm images because the longer wavelength is less likely to be contaminated by AGN emission, which can still contribute a significant fraction of the 70 μm emission (Shimizu et al. 2017).

The PSF of the WISE 22 μm and PACS 160 μm images are rather large (12'') when compared with the size of the CO beams (14''–22'') and can therefore affect the measurement of the beam corrections. The images that we are using to trace the distribution of the FIR emission are not maps of the "true" distribution; instead, they are maps of the "true" distribution convolved with the PSF of the FIR telescope. To correct for the effect of the PSF, we use a simulated galaxy gas profile, following the procedure described in Saintonge et al. (2012). For each galaxy, we create a model galaxy simulating a molecular gas disk following an exponential profile, with a scale length equivalent to its half-light radius. Then, the profile is tilted according to the inclination of the galaxy, and we measure the amount of flux that would be observed from this model galaxy, using an aperture corresponding to the size of the beam (Fsim). Then, we convolve the galaxy profile with a 2D Gaussian with the FWHM equal to the size of the PSF of the image, and we measure again the flux within the beam radius ( ). By taking the ratio of these two measurements, we estimate how much the flux changes due to the effect of the PSF:

). By taking the ratio of these two measurements, we estimate how much the flux changes due to the effect of the PSF:

This correction is in the range 1.04–1.27. We apply this PSF correction to the beam correction obtained from the IR images:

We finally apply this factor to the r31 ratios:

The final beam corrections ( ) for the BASS sample are in the range 1.05–1.70, with a mean value of 1.27. For the xCOLD GASS sample, they span a similar range between 1.08 and 1.80, with a mean of 1.31. The corrections for the xCOLD GASS samples are larger because of the larger difference between the two beams (22'' for the CO(1–0) beam versus 14'' for the CO(3–2) beam), compared to the BASS sample (20'' for the CO(2–1) beam versus 14'' for the CO(3–2) beam). In order to check that the beam corrections do not have an effect on our analysis, we look at the relation between r31 and galaxy angular size or the beam-correction values. We do not find any dependence of r31 on the beam corrections or on the angular size of the galaxies (see Appendix).

) for the BASS sample are in the range 1.05–1.70, with a mean value of 1.27. For the xCOLD GASS sample, they span a similar range between 1.08 and 1.80, with a mean of 1.31. The corrections for the xCOLD GASS samples are larger because of the larger difference between the two beams (22'' for the CO(1–0) beam versus 14'' for the CO(3–2) beam), compared to the BASS sample (20'' for the CO(2–1) beam versus 14'' for the CO(3–2) beam). In order to check that the beam corrections do not have an effect on our analysis, we look at the relation between r31 and galaxy angular size or the beam-correction values. We do not find any dependence of r31 on the beam corrections or on the angular size of the galaxies (see Appendix).

We note that the line ratios presented in this paper are measured in the central region of the galaxies and might not be representative of the line ratio of the entire galaxy. Resolved studies of the CO line ratios in nearby galaxies find that the excitation tends to be higher in the central part than at larger radii (Leroy et al. 2009; Wilson et al. 2009). With the beam corrections, we want to correct for the fact that the beams of the two transitions have different sizes, but they still represent only the central part of the galaxy.

(2) Beam-to-total luminosity corrections:

To calculate the total CO(1–0) emission and molecular gas mass, we need to apply a correction to extrapolate the CO(1–0) emission within the beam to the total CO(1–0) luminosity. For the xCOLD GASS sample, we retrieve these values from the xCOLD GASS catalog (Saintonge et al. 2017). They are in the range 1.02–1.95. For the BASS sample, we use the method describe above to estimate the total amount of CO emission. We measure the total IR 160 μm emission of the galaxy within a radius big enough to include the entire galaxy, paying attention not to include any emission not related to the galaxy. We determine the radius until which we integrate the flux based on the curve of growth of the galaxy profile. For compact sources, the radius extends until ∼60'', while for the more extended and nearby galaxies, we measure the flux within a radius up to 140''.

Then we take the ratio between the flux from the map multiplied by the CO(2–1) beam sensitivity, measured as explained above, and the total IR flux, and we use this value to extrapolate the total CO(2–1) flux. The beam corrections for BASS are in the range 1.46–15.66. For the analysis in Section 4, we use only galaxies with angular diameter D < 100'', for which the beam corrections are <2.4, to avoid galaxies for which the CO emission within the beam is not representative of the total CO emission. For the angular size D of xCOLD GASS and SLUGS, we use D = D25, i.e., the optical diameter derived from SDSS g band. For BASS, we use D = 2 × Rk20, where Rk20 is the isophotal radius at 20 mag arcsec−2 in the K band. We expect the sizes measured in the g band and in the K band to be similar (Casasola et al. 2017). The beam-correction values can be found in Tables 3 and 4.

3.5. Total Molecular Gas Mass

We use two different CO-to-H2 conversion factors: for normal SFGs, we adopt a Galactic conversion factor

/(K km s−1 pc2) (Strong & Mattox 1996; Abdo et al. 2010; Bolatto et al. 2013) and for "ULIRG-type" galaxies, we use αCO = 1

/(K km s−1 pc2) (Strong & Mattox 1996; Abdo et al. 2010; Bolatto et al. 2013) and for "ULIRG-type" galaxies, we use αCO = 1  /(K km s−1 pc2) (Bolatto et al. 2013). To distinguish between normal SFGs and "ULIRG-type" galaxies, we apply the selection criterion described in Saintonge et al. (2012), which is based on the FIR luminosity and on the dust temperature. According to this criterion, we apply the "ULIRG-type" conversion factor to galaxies with

/(K km s−1 pc2) (Bolatto et al. 2013). To distinguish between normal SFGs and "ULIRG-type" galaxies, we apply the selection criterion described in Saintonge et al. (2012), which is based on the FIR luminosity and on the dust temperature. According to this criterion, we apply the "ULIRG-type" conversion factor to galaxies with  and

and  . For the other galaxies, we use the Galactic conversion factor. For the BASS sample, we also need to apply a conversion from CO(2–1) to CO(1–0) line luminosity, which is explained in Section 3.2.

. For the other galaxies, we use the Galactic conversion factor. For the BASS sample, we also need to apply a conversion from CO(2–1) to CO(1–0) line luminosity, which is explained in Section 3.2.

4. CO Line Ratios

4.1. r31 and Star Formation

In this section, we look at the r31 distribution for AGN and SFGs and investigate the relation between r31 and galaxy global properties. For this part of the analysis, we exclude from the sample the galaxies with large angular size (diameter D > 100''), in order to avoid galaxies for which the luminosity measured within the beam is not representative of its total emission. The sample used in this section consists of 25 galaxies from xCOLD GASS, 20 from BASS, and 8 from SLUGS.

The r31 values in the xCOLD GASS sample are in the range 0.25–1.15 and the mean value is 0.55 ± 0.05, with a standard deviation of 0.22. This value is consistent with observations of low-redshift galaxies. Mao et al. (2010) found a mean value r31 = 0.61 ± 0.16 in their sample of normal SFGs. Papadopoulos et al. (2012) found a higher mean value  in a sample of nearby LIRGs, which are expected to have higher r31 given their higher SSFR and SFE. Also, Yao et al. (2003) found a higher mean value r31 = 0.66 in their sample of IR-luminous galaxies. The r31 values in the BASS AGN sample span a very similar range to the xCOLD GASS sample 0.22–1.23, with a mean value 0.53 ± 0.06 (standard deviation 0.25). For the SLUGS sample, the r31 values are in the range 0.32–0.89 with a mean value 0.58 ± 0.07 (standard deviation 0.20). The mean value of the total sample is 〈r31〉 = 0.55 ± 0.03 (standard deviation 0.23).

in a sample of nearby LIRGs, which are expected to have higher r31 given their higher SSFR and SFE. Also, Yao et al. (2003) found a higher mean value r31 = 0.66 in their sample of IR-luminous galaxies. The r31 values in the BASS AGN sample span a very similar range to the xCOLD GASS sample 0.22–1.23, with a mean value 0.53 ± 0.06 (standard deviation 0.25). For the SLUGS sample, the r31 values are in the range 0.32–0.89 with a mean value 0.58 ± 0.07 (standard deviation 0.20). The mean value of the total sample is 〈r31〉 = 0.55 ± 0.03 (standard deviation 0.23).

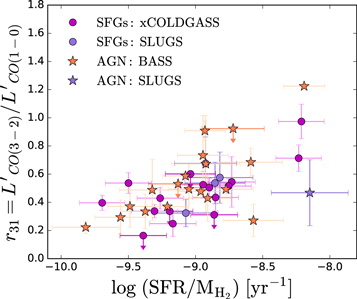

We investigate how the ratio r31 evolves as a function of SFR, SSFR, and SFE (Figure 2). We find a general trend for r31 to increase as these quantities increase (Pearson correlation coefficients R = 0.26–0.60). To illustrate the evolution of r31, we divide the total sample in bins of 0.5 dex according to the quantity on the x-axis (SFR, SSFR, or SFE) and calculate the mean values of r31 in these bins. The mean values are shown as black points in the plots, with the error bars showing the standard errors on the mean values. For bins that contain fewer than three objects, we do not show the mean values.

Figure 2. Ratio r31 =  /

/ as a function of star formation rate (SFR), specific star formation rate (SSFR = SFR/M

as a function of star formation rate (SFR), specific star formation rate (SSFR = SFR/M ), and star formation efficiency (SFE=SFR/

), and star formation efficiency (SFE=SFR/ ) for the xCOLD GASS, BASS, and SLUGS samples. The black points show the mean values of the total sample in bins of 0.5 dex, with the error bars showing the standard errors on the mean values. The dashed line connects the mean values to help to visualize the trends. In each plot, we show the p-value of the null hypothesis that there is no correlation, calculated using Kendall's rank correlation test for censored data.

) for the xCOLD GASS, BASS, and SLUGS samples. The black points show the mean values of the total sample in bins of 0.5 dex, with the error bars showing the standard errors on the mean values. The dashed line connects the mean values to help to visualize the trends. In each plot, we show the p-value of the null hypothesis that there is no correlation, calculated using Kendall's rank correlation test for censored data.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn order to properly take into account the upper limits on the r31 values, we apply the principles of survival analysis (Feigelson & Nelson 1985). We perform Kendall's rank correlation test for censored data (i.e., data with upper limits) as given in Brown et al. (1974). The test gives  for the relation of r31 with SFR, SSFR, and SFE, respectively. The p-values of the correlation with SFR and SFE are <0.05, meaning that we can reject the null hypothesis that there is no association between the two quantities. The strongest relation is the one with the SFE (largest Pearson correlation coefficient R = 0.6). The correlation of r31 with the SFE is significantly different from the correlation of r31 with the SFR and SSFR, according to the Fisher Z-test (p-value = 0.03 and

for the relation of r31 with SFR, SSFR, and SFE, respectively. The p-values of the correlation with SFR and SFE are <0.05, meaning that we can reject the null hypothesis that there is no association between the two quantities. The strongest relation is the one with the SFE (largest Pearson correlation coefficient R = 0.6). The correlation of r31 with the SFE is significantly different from the correlation of r31 with the SFR and SSFR, according to the Fisher Z-test (p-value = 0.03 and  , respectively). This trend has already been reported by Yao et al. (2003) and Leech et al. (2010) for samples of IR-luminous galaxies and LIRGs. If we consider the r31 ratio to be a proxy for the ratio of relatively dense to very diffuse molecular gas, the correlation between r31 and SFE suggests that galaxies with a higher fraction of dense molecular gas tend to have higher SFE. The connection between r31 and gas density is investigated further in Section 5. We find that the r31 ratio tends to increase with SFE, but there is a large scatter in the relation. It is then likely that other factors contribute to regulate the r31 ratio.

, respectively). This trend has already been reported by Yao et al. (2003) and Leech et al. (2010) for samples of IR-luminous galaxies and LIRGs. If we consider the r31 ratio to be a proxy for the ratio of relatively dense to very diffuse molecular gas, the correlation between r31 and SFE suggests that galaxies with a higher fraction of dense molecular gas tend to have higher SFE. The connection between r31 and gas density is investigated further in Section 5. We find that the r31 ratio tends to increase with SFE, but there is a large scatter in the relation. It is then likely that other factors contribute to regulate the r31 ratio.

4.2. Comparison of SFGs and AGN

We divide the sample into AGN (20 BASS objects and 1 AGN from SLUGS) and SFGs (25 xCOLD GASS galaxies and the remaining 7 SLUGS galaxies) to investigate whether we see any difference in the r31 values between these two classes of objects. The two samples have different distributions of specific star formation rate (SSFR=SFR/M*): the AGN host galaxies have lower values of SSFR ![$(-10.8\,\lt \mathrm{logSSFR}/[{\mathrm{yr}}^{-1}]\,\lt -8.8)$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/889/2/103/revision1/apjab6221ieqn70.gif) than the SFGs

than the SFGs ![$(-10.6\lt \mathrm{logSSFR}/[{\mathrm{yr}}^{-1}]\lt -8.3)$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/889/2/103/revision1/apjab6221ieqn71.gif) . To remove the effect of the different SSFRs in the two samples, we match the samples in SSFR, and we look again at the distribution of r31 in SFGs and AGN. This is important because of the correlation between SSFR and SFE (Saintonge et al. 2011b, 2016). We pair every SFG with the AGN host galaxy which has the most similar value of SSFR. The results are shown in Figure 3. The mean r31 for the matched samples are consistent with each other: r31 = 0.52 ± 0.04 for SFGs and 0.53 ± 0.06 for AGN. To test whether the two samples have different r31 distributions at the same SSFR, we do a Two Sample test using the survival analysis package ASURV (Feigelson & Nelson 1985), which allows to take into account upper limits. We find that the two samples are not significantly different according to the Gehan's, Logrank, and Peto-Prentice's Two Sample Tests (p-value = 0.57–0.79). So our results suggest that there is no clear difference in the r31 values due to the AGN contribution.

. To remove the effect of the different SSFRs in the two samples, we match the samples in SSFR, and we look again at the distribution of r31 in SFGs and AGN. This is important because of the correlation between SSFR and SFE (Saintonge et al. 2011b, 2016). We pair every SFG with the AGN host galaxy which has the most similar value of SSFR. The results are shown in Figure 3. The mean r31 for the matched samples are consistent with each other: r31 = 0.52 ± 0.04 for SFGs and 0.53 ± 0.06 for AGN. To test whether the two samples have different r31 distributions at the same SSFR, we do a Two Sample test using the survival analysis package ASURV (Feigelson & Nelson 1985), which allows to take into account upper limits. We find that the two samples are not significantly different according to the Gehan's, Logrank, and Peto-Prentice's Two Sample Tests (p-value = 0.57–0.79). So our results suggest that there is no clear difference in the r31 values due to the AGN contribution.

Figure 3. Ratio r31 =  /

/ as a function of SFE (SFE = SFR/M(H2)) for SFGs (circles) and AGN (stars). The SFG and AGN samples are matched in SSFR: at every SFG corresponds the AGN host galaxy with the most similar value of SSFR.

as a function of SFE (SFE = SFR/M(H2)) for SFGs (circles) and AGN (stars). The SFG and AGN samples are matched in SSFR: at every SFG corresponds the AGN host galaxy with the most similar value of SSFR.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageMao et al. (2010) found a higher  in AGN than in normal SFGs (

in AGN than in normal SFGs ( ). They however do not control for the SSFR, so it is possible that the difference in r31 is partly due to differences in SSFR between the two samples and not to the effect of the AGN. They also find higher r31 values in starbursts (

). They however do not control for the SSFR, so it is possible that the difference in r31 is partly due to differences in SSFR between the two samples and not to the effect of the AGN. They also find higher r31 values in starbursts ( ) and in ULIRGs (r31 = 0.96 ± 0.14) than in AGN. Additionally, most of the galaxies in their sample have rather large angular size (optical diameter D25 > 100'') and thus the CO beam is sampling a smaller region around the nucleus. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that the AGN could have a large impact on the observed r31 line ratio.

) and in ULIRGs (r31 = 0.96 ± 0.14) than in AGN. Additionally, most of the galaxies in their sample have rather large angular size (optical diameter D25 > 100'') and thus the CO beam is sampling a smaller region around the nucleus. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that the AGN could have a large impact on the observed r31 line ratio.

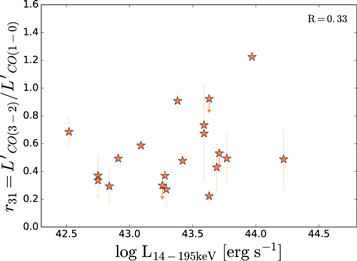

We look at the relation between r31 and hard X-ray luminosity (14–195 keV) for the BASS sample, but we do not find a clear trend between the two quantities (see Figure 9 in the Appendix), which suggests that the X-ray flux is not the main parameter affecting this line ratio. Even though the X-ray radiation may contribute to enhance the r31 ratio in the nuclear region, as is shown later in Section 5.2, it is probably not enough to regulate the CO excitation in the entire galaxy.

We conclude that there is no significant difference between the values of r31 of AGN and SFGs.

5. Modeling: UCL-PDR

In order to better understand which physical parameters influence the line ratios r21 and r31, we model the CO emission lines using a photon-dissociation region (PDR) code. Our goal is to test which are the physical quantities that have the largest effect on the CO line ratios, and which values of these quantities can reproduce our observations.

We employ the 1D UCL-PDR code, developed by Bell et al. (2005, 2006) and upgraded by Bayet et al. (2011). The latest version of the code is presented in Priestley et al. (2017). The code models the gas cloud as a semi-infinite slab with a constant density, illuminated from one side by a far-ultraviolet (FUV) radiation field. At each depth point in the slab, the code calculates the chemistry and thermal balance of the gas self-consistently and returns, for every element, the gas chemical abundances, emission-line strengths, and gas temperature. Surface reactions on dust grains are not included.

The gas is cooled by the emission from collisionally excited atoms and molecules and by the interactions with the cooler dust grains (Bell et al. 2006). We include in our model the cooling from the following lines: Lyman α, 12C+, 12C, 16O, 12CO, and the para and ortho H2 and H2O states. Table 5 shows the elements included in the chemical network and their initial abundances relative to hydrogen, where depletion in the dust by some elements is already taken into consideration. For the values of the initial elemental abundances, we follow Bell et al. (2006). We set  (where

(where  is the volume density of hydrogen nuclei

is the volume density of hydrogen nuclei

) following Bell et al. (2005).

) following Bell et al. (2005).

Table 5. Initial Elemental Abundances Used in the UCL-PDR Code Relative to the Hydrogen Nuclei

| Element | Abundance |

|---|---|

| He |

|

| O |

|

| C+ |

|

| N |

|

| Mg(+) |

|

| S(+) |

|

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

We calculate the integrated line intensity of the CO emission lines as described in Bell et al. (2006). The opacity is included in the calculation of each coolant transition along each path (Bell et al. 2006; Banerji et al. 2009). The intensity I in units of erg s−1 cm−2 sr−1 is calculated by integrating the line emissivity Λ over the depth into the cloud L:

where Λ has units of erg s−1 cm−3, and the factor of 2π takes into account the fact that the photons only emerge from the edge of the cloud/slab.

The velocity-integrated antenna temperature in units of K km s−1 is calculated from the intensity as

where c is the speed of light, ν the frequency of the line, and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

The model is computed from AV = 0 to AV = 10. We choose the maximum AV value to be representative of the average visual extinction measured in dark molecular clouds. At these AV, the temperature is already ≤10 K and the gas enters the dense molecular cloud regime, where the freeze out starts to be efficient, and it can no longer be considered a PDR (Bergin & Tafalla 2007).

We define the r31 line ratio as the ratio between the integrated antenna temperatures:

where ν is the frequency of the line. In an analogous way, we calculated r21. This ratio is equivalent to the observed  luminosity ratio that we studied in the previous section.

luminosity ratio that we studied in the previous section.

5.1. CO Line Ratios from Modeling

We define a grid of models, varying three parameters: the volume density of hydrogen nuclei (

), the FUV radiation field, and the cosmic-ray ionization rate. The values assumed in our models are summarized in Table 6. The standard Galactic value of the cosmic-ray ionization rate is

), the FUV radiation field, and the cosmic-ray ionization rate. The values assumed in our models are summarized in Table 6. The standard Galactic value of the cosmic-ray ionization rate is  s−1 (Shaw et al. 2008). We select a range up to two orders of magnitude higher to take into account the fact that in AGN, the cosmic-ray density is higher (George et al. 2008 and references therein). Recent studies found that cosmic-ray ionization rates can be up to 100 times the Galactic value in particular regions of the interstellar medium (Indriolo & McCall 2012; Bisbas et al. 2015, 2017; Indriolo et al. 2015). Even though these extreme conditions may happen close to the source of cosmic rays, i.e., the AGN, the cosmic-ray ionization rate will decrease quickly with increasing H2 column density (Padovani et al. 2009; Schlickeiser et al. 2016). Because we are studying integrated CO fluxes within a beam that has a minimum size of ∼2 kpc, we do not expect to have an average cosmic-ray ionization rate higher than 10 times the Galactic value in the region covered by the CO beam.

s−1 (Shaw et al. 2008). We select a range up to two orders of magnitude higher to take into account the fact that in AGN, the cosmic-ray density is higher (George et al. 2008 and references therein). Recent studies found that cosmic-ray ionization rates can be up to 100 times the Galactic value in particular regions of the interstellar medium (Indriolo & McCall 2012; Bisbas et al. 2015, 2017; Indriolo et al. 2015). Even though these extreme conditions may happen close to the source of cosmic rays, i.e., the AGN, the cosmic-ray ionization rate will decrease quickly with increasing H2 column density (Padovani et al. 2009; Schlickeiser et al. 2016). Because we are studying integrated CO fluxes within a beam that has a minimum size of ∼2 kpc, we do not expect to have an average cosmic-ray ionization rate higher than 10 times the Galactic value in the region covered by the CO beam.

Table 6. Parameters Used in the Grid of UCL-PDR Models

| Gas Density | FUV Radiation Field | Cosmic-Ray |

|---|---|---|

( ) ) |

(FUV) | Ionization Rate ( ) ) |

(cm

|

(Draine (a)) |

s−1) s−1) |

| 102 | 10 | 2.5 (b) |

| 103 | 102 | 25 |

| 104 | 103 | 250 |

| 105 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

Note. (a) 1 Draine  erg s−1 cm−2. The FUV radiation is defined by the standard Draine field (Draine 1978; Bell et al. 2006). (b) Standard Galactic value (Shaw et al. 2008).

erg s−1 cm−2. The FUV radiation is defined by the standard Draine field (Draine 1978; Bell et al. 2006). (b) Standard Galactic value (Shaw et al. 2008).

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

We note that a limitation of our approach is the degeneracy of the low-J CO line ratios to the average state of the ISM (Aalto et al. 1995). Using only two low-J CO line ratios to derive physical properties of the gas can lead to large uncertainties. Additionally, it is possible that models with line ratios that match the observations have individual intensities that are unrealistic. We compare the individual line intensities from the UCL-PDR models which match the observed r31 line ratios, with the observed line intensities (both for CO(3–2) and for CO(1–0)). For all galaxies, we find that the line intensities from the models are higher than the observed line intensities (by a factor that varies between 1.7 and 124). This can be explained by beam dilution effects. The UCL-PDR models assume a 100% filling factor. The observed PDR regions typically do not fill the entire beam and thus the emission from the PDR regions is diluted when averaging over the beam. As a result, the observed intensities are lower than the ones predicted from the models. Even given these limitations, qualitatively the UCL-PDR models can provide an indication of which physical parameters have the highest impact in regulating the CO line ratios.

Figure 4 shows the modeled line ratios r21 (left) and r31 (right) as a function of  . The colors indicate different values of the FUV radiation field and different line types correspond to different cosmic-ray ionization rates. The parameter that has the largest effect on the line ratios is the density

. The colors indicate different values of the FUV radiation field and different line types correspond to different cosmic-ray ionization rates. The parameter that has the largest effect on the line ratios is the density  . As expected, there is a clear increase in both line ratios with

. As expected, there is a clear increase in both line ratios with  . The r21 values are in the range 0.3–1.1. The r31 value goes from 0.01 at

. The r21 values are in the range 0.3–1.1. The r31 value goes from 0.01 at  = 102 cm−3 to 1 at

= 102 cm−3 to 1 at  = 105 cm−3.

= 105 cm−3.

Figure 4. CO line ratios  (left) and

(left) and  (right) predicted from UCL-PDR as a function of gas density

(right) predicted from UCL-PDR as a function of gas density  . The colors indicate models with different FUV values: 101 Draine (blue), 102 Draine (orange), 103 Draine (magenta). The line styles indicate models with different cosmic-ray ionization rates:

. The colors indicate models with different FUV values: 101 Draine (blue), 102 Draine (orange), 103 Draine (magenta). The line styles indicate models with different cosmic-ray ionization rates:  s−1 (full line), 2.5 × 10−16 s−1 (dashed line), 2.5 × 10−15 s−1 (dotted–dashed line).

s−1 (full line), 2.5 × 10−16 s−1 (dashed line), 2.5 × 10−15 s−1 (dotted–dashed line).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe FUV radiation field has very little effect on the line ratio. The only visible difference is for the r21 ratio: at  = 102 cm−3, it decreases from ∼0.45 for FUV = 10 Draine15