Abstract

Mantra is a free and open-source software package for object tracking. It is specifically designed to be used as a tool for response collection in psychological experiments and requires only a computer and a camera (a webcam is sufficient). Mantra is compatible with widely used software for creating psychological experiments. In Experiments 1 and 2, we validated the spatial and temporal precision of Mantra in realistic experimental settings. In Experiments 3 and 4, we validated the spatial precision and accuracy of Mantra more rigorously by tracking a computer controlled physical stimulus and stimuli presented on a computer screen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Object tracking is a powerful method of response collection. There are many examples of studies that have addressed important questions by using object tracking. For example, in a study by Tipper, Howard, and Jackson (1997), participants reached for a target stimulus (a wooden block) while the positions of their hands were tracked. In addition to the target, a distractor stimulus was presented. The crucial finding was that the reaching trajectory of the hand systematically veered away from the distractor. The authors interpreted this as evidence for competition between the target and the distractor, which is resolved by inhibiting the distractor location. Another example that illustrates the usefulness of object tracking is a study by Brenner and Smeets (1996). In their study, participants picked up a target stimulus (a brass disk) while their thumbs and index fingers were tracked in order to measure hand opening. The apparent size of the target was manipulated by presenting it among converging lines in various configurations. The crucial finding was that this perceptual illusion did affect the participants' judgments of the size of the target, but did not affect how wide they opened their hands to reach for the target. Brenner and Smeets interpreted this finding as evidence for separate visual streams for action and perception (Goodale & Milner, 1992). Both the study by Tipper et al. and that by Brenner and Smeets illustrate clearly that object tracking is a unique and flexible tool, which allows researchers to investigate issues that cannot be investigated otherwise.

Even in situations in which the use of a keyboard may be considered an adequate form of response collection, object tracking can provide additional information. For example, keyboard presses are often used to investigate whether responses are faster (or slower) in one condition than in another condition. This approach has a rich history and forms the basis of many classic psychological paradigms (e.g., Donders, 1969; Posner, 1980). However, some questions are difficult to answer on the basis of response time alone. For example, is there a difference in the time of movement–onset or is there a difference in the velocity of the movement? Both possibilities could lead to a decrease in response time as measured using a keyboard. This question, and many others, can easily be investigated by tracking the location of a participant's hand throughout a trial.

Despite the obvious advantages of object tracking as a method of response collection, object-tracking systems are used sparingly by experimental psychologists. The reason is that the required equipment is generally expensive and is not part of the “default set of equipment” found in most psychological laboratories. In the present article, we introduce Mantra, a system for object tracking, which has three crucial advantages. First, Mantra is released under an open-source license and is available free of charge. Second, Mantra requires only a computer and a camera (an ordinary webcam is sufficient). Therefore, Mantra allows object tracking with general purpose, widely available equipment. Third, Mantra is designed specifically as a tool for experimental psychology. Therefore, it integrates painlessly with software for creating psychological experiments, such as E-Prime (Schneider, Eschman, & Zuccolotto, 2002), PsychoPy (Peirce, 2007), PyEPL (Geller, Schleifer, Sederberg, Jacobs, & Kahana, 2007), and OpenSesame (Mathôt & Theeuwes, 2010). As compared with systems such as the Liberty tracking system (Polhemus), TrakSTAR (Ascension Technology Corporation), or the Optotrak System (Northern Digital), Mantra offers basic functionality. However, for many purposes, such as the study by Tipper and colleagues (1997) described previously, this basic functionality is precisely what is needed.

In the first section of the present article, we provide a brief, nontechnical description of Mantra. The following sections describe four experiments. Experiment 1 is a replication of the Müller-Lyer illusion (Müller-Lyer 1889), which we have designed to validate the spatial precision of Mantra in a realistic experimental setting. Experiment 2 is a variant of the additional singleton paradigm (Theeuwes, 1994), which we have designed to validate the temporal precision of Mantra, also in a realistic experimental setting. In Experiments 3 and 4, we investigated the spatial precision and accuracy of Mantra more rigorously, by tracking a computer controlled physical stimulus and stimuli presented on a computer display. A detailed description of Mantra, installation packages, source-code, and experimental data can be downloaded from http://www.cogsci.nl/mantra.

Usage

System requirements

Mantra is available as an open-source software package for Linux and integrates directly with experiments created in E-Prime (Windows XP) and Python (cross-platform). Mantra will run on any modern computer system, including low-end systems, such as the Intel Atom-based netbook used in Experiment 3. A camera (e.g., a webcam) is required.

Defining objects

The first step in using Mantra is to define one or more objects. Object definitions are based on color, which provides a robust and computationally cheap way to track multiple objects simultaneously and unambiguously. Therefore, it is important to use distinctly colored objects. Stickers or colored pieces of paper can be attached to objects that do not have a distinct color themselves. The number of objects that can be tracked simultaneously is determined by the number of colors that are sufficiently distinct. In turn, this depends on factors such as lighting and camera settings. In practice, it is feasible to track up to five objects (Fig. 1c). In order to define an object, you simply hold it in front of the camera and select it in the object-definition window (Fig. 1b). The color of the selected pixel is taken as the object-defining color. The object now turns green, whereas the rest of the image turns red. This allows you to determine visually if the object is reliably detected and is not confused with other objects. By default, Mantra compensates for luminosity, by representing color values relative to luminosity [e.g., Rrel = R – (R + G + B)/3]. Therefore, detection remains reliable even if luminosity varies: A red object that has been defined in the light is also detected in the shade.

Screenshots of Mantra. a The main window contains controls to define objects, start tracking, change camera settings, and so on. b To define an object, you click on it in the object-definition window. The selected object turns green, whereas the rest of the image turns red. This allows you to check whether an object is reliably detected before you start tracking. c During tracking, you can monitor the position of all objects. In this example, the five fingers of a hand are being tracked

Tracking

After all objects have been defined, you can start tracking. While tracking is in progress, you can monitor the location of the objects (Fig. 1c). The average location of all matching pixels is taken as the object's location (x, y). A z-coordinate is also available, which is defined as the maximum of the width and height of the object and can be used as a (very) coarse approximation of distance. The velocity and acceleration of the object are determined as well. If the velocity exceeds a certain threshold, a movement start is signaled. If the velocity then drops below a second threshold, a movement end is signaled. All data are logged as plain text to a file.

In most cases, the temporal resolution will be limited by the frame rate of the camera. Most webcams, including the webcams that we have used in our experiments, have a frame rate of 25 Hz, which is equivalent to a temporal resolution of 40 ms. On a 1.66-GHz netbook, tracking at 25 Hz, CPU consumption is around 53%, irrespective of the number of objects that are tracked (one object, 53.1%; five objects, 53.7%).

The spatial resolution depends on two factors. The first factor is the resolution of the camera. In our experiments, we have used a camera with a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels, which is a typical resolution for webcams. The second factor is the distance between the camera and the object. For obvious reasons, spatial resolution is highest for objects near the camera. There is always a small jitter due to ambiguities in the separation between object and background (Figs. 3b and 7b, c, d). Under good conditions (i.e., with proper lighting, well-defined objects, and using a camera with a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels), objects can be tracked with a spatial precision of up to 0.3° (corresponding to about 2 mm in a regular setup; see Experiment 3). Under optimal conditions (such as tracking ideal stimuli on a computer display), a measurement error of less than 0.1° is even feasible (Experiment 4) (Table 1).

Communication

Because Mantra is primarily intended as a data-collection tool for experiments, communication between the experiment and Mantra is crucial. Example code is provided in Table 2 (E-Basic) and Table 3 (Python). The first step is to establish a connection between the experiment and Mantra. In order to do this, one needs to know the IP address of the computer running Mantra, which depends on your network configuration. You must also know the port on which Mantra is listening, which is displayed in the tracking preview window (Fig. 1c). After a connection has been established, the experiment can send information to Mantra. For example, the experiment can write messages to the Mantra log file to indicate the start and end of a trial. The experiment can also retrieve information from Mantra. The coordinates of an object can be queried (Experiment 1) or the experiment can wait for the start or end of a movement (Experiment 2).

Experiment 1

The first aim of Experiment 1 was to validate the spatial precision of Mantra in a realistic experimental setting. To this end, we set out to replicate the Müller-Lyer illusion (1889). The Müller-Lyer illusion refers to the fact that people tend to overestimate the length of a line segment surrounded by inward-pointing arrowheads, relative to a line segment surrounded by outward- pointing arrowheads. In our experiment, participants controlled the length of a target line segment by adjusting the distance between their thumbs and index finger, which were tracked by Mantra. A replication of the Müller-Lyer illusion in this way would be a compelling demonstration of the spatial precision of the Mantra system.

The second aim of Experiment 1 was to provide a demonstration of how Mantra can be used in combination with E-Prime (Schneider et al., 2002). Because E-Prime is a widely used package for creating psychological experiments, it is crucial that Mantra integrates well with E-Prime.

Method

Participants, stimuli, and procedure

Five observers who were naive to the purpose of the experiment and one of the authors (S.M.) participated in the experiment (age range 18–27 years). All of the participants reported normal or corrected vision. The experiment was conducted in a well-lit room.

Before the start of each trial, a gray fixation dot was presented on a black background for 500 ms (Fig. 2a), followed by the presentation of two line segments that were 4.2° above and below the fixation dot. One of the line segments was surrounded by inward-pointing arrowheads; the other line segment was surrounded by outward-pointing arrowheads. One of the line segments (the match) was gray and had a fixed length (a random value between 2.5° and 4.2°). The other line segment (the target) was green, and its length was adjusted online, according to the distance between the thumb and index finger of the participant (see the following Apparatus, Software, and Response Collection section). The arrowheads consisted of two lines, 1.7° in length. The arrowhead style of the target (inward target/outward match or outward target/inward match) and the location of the target (target above/match below or target below/match above) were fully randomized. Participants were instructed to adjust the length of the target line segment and to press the spacebar when they felt that both line segments were equally long. It was emphasized that response time was not important. The experiment consisted of 16 practice trials, followed by 128 experimental trials.

Paradigm, setup, and response collection in Experiment 1. a Participants matched the length of the target line segment (green) to that of the match line segment and pressed the spacebar when they felt that both line segments were equally long. b The camera pointed downward. Participants rested their right hands on the table surface underneath the camera. Participants manipulated the length of the target line segment by changing the distance between their thumbs and index fingers, which were tracked using Mantra

Apparatus software, and response collection

The experiment was run on a desktop computer (Intel Core Duo, 3 GHz, Windows XP) running E-Prime 1.2. Mantra 0.2 was run on a laptop running Linux (Intel Pentium T4300, 2.1 Ghz, Ubuntu 9.10). Both computers were connected through an ethernet cable. For image acquisition, a Logitech webcam was used, with a frame rate of 25 Hz and a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels. The webcam was mounted on top of the experimental display and pointed downward (Fig. 2b). Participants wore a green paper “fingercap” on their thumb and an orange fingercap on their index finger. The length of the target line-segment on the display (in display pixels) was adjusted online to twice the distance (in webcam pixels) between the thumb and index finger.

Results

Target length was defined as the length of the target line segment relative to the match line segment. Trials in which target length was less than 50% or more than 150% were excluded (0.1%). In total, 99.9% of the trials were included in the analysis.

A two-tailed paired-samples t test revealed that target length was larger in the target-outward/match-inward condition (M = 105.4%; SE = 1.3) than in the target-inward/match-outward condition [M = 96.8%, SE = 1.7; t(5) = 3.0; p < .05; Fig. 3a]. All participants showed this effect, which reflects the Müller-Lyer (1889) illusion.

The results of Experiment 1. a Participants overestimated the length of the target line segment when it was surrounded by inward-pointing arrows (and subsequently underadjusted its length), relative to when the target line segment was surrounded by outward-pointing arrows. This effect reflects the Müller-Lyer (1889) illusion. Error bars represent 95% within-subjects confidence intervals (Cousineau, 2005). b Unsmoothed target length relative to the match for a single, representative trial. This example shows the typical, slow oscillations in the size of the target line segment while the participant is attempting to match its length. In addition, this example shows that there is little jitter due to noise (the small, rapid oscillations)

Figure 3b shows target length over time for a single, representative trial. A number of things are apparent from this graph. First, the oscillations reflect the typical tendency to iteratively adjust, overshoot, and readjust the length of the target line segment. Second—and, more importantly—jitter resulting from measurement error is small. For example, during the first 400 ms of this particular trial (the 10 frames before start of the first oscillation), the target-length standard deviation is 0.4%.

Discussion

In Experiment 1, we replicated the Müller-Lyer (1889) illusion. Participants controlled the length of a target line segment by adjusting the distance between thumbs and index fingers. The thumb and index finger were tracked on a computer running Mantra and communicated to a second computer running the experiment (programmed in E-Prime), which dynamically adjusted the length of the target line segment on the display.

Since it is conceivable that color affects perceived size, a potential concern is that the target line segment was always green, whereas the match line segment was always gray. However, this would lead to a systematic over- or underestimation of the size of the target line segment relative to that of the match line-segment, and cannot account for the Müller-Lyer (1889) illusion in the present experiment.

Two important conclusions can be drawn. First, Experiment 1 clearly shows that the position of multiple objects can be tracked reliably and precisely using Mantra. Second, Experiment 1 shows that Mantra integrates well with E-Prime.

Experiment 2

The first aim of Experiment 2 was to validate the temporal precision of Mantra. To this end, we created a variant of the additional singleton paradigm, in which participants made a speeded report of the orientation of a line segment within a uniquely shaped placeholder. On the basis of the literature, we expected that the presence of a distractor would result in increased response times, due to attention being captured by the distractor (Theeuwes, 1994). In addition, we expected that this distractor–interference effect would be largest if the distractor was presented near the target, due to increased competitive interactions between target and distractor at close spatial separations (Mathôt, Hickey, & Theeuwes, 2010; Mounts, 2000). In one condition, participants moved their index fingers, which were tracked by Mantra, to the left or to the right to make a response. In order to directly compare Mantra responses to keypress responses, we also included a condition in which participants responded using a keyboard.

The second aim of Experiment 2 was to demonstrate how Mantra can be used in combination with Python. Interoperability with Python ensures that the use of Mantra does not require access to proprietary software. A number of packages are available for creating psychological experiments in Python, such as PsychoPy (Peirce, 2007), PyEPL (Geller et al., 2007), and OpenSesame (Mathôt & Theeuwes, 2010).

Method

Participants, stimuli, and procedure

Three observers who were naive to the purpose of the experiment and one of the authors (S.M.) participated in the experiment (age range 25–38 years). All participants reported normal or corrected vision. The experiment was conducted in a well-lit room.

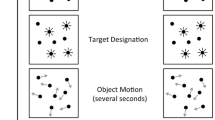

Before the start of each trial, a fixation dot was presented for 600 ms (Fig. 4a), followed by the presentation of six premasks (size = 3.3°), arranged in a circle (r = 10°), centered around the fixation dot. All stimuli were gray and were presented on a black background. Premasks consisted of a placeholder (a circle or a square, fully randomized) containing six line segments titled 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°, 120° and 150°. After 600 ms, all but one of the line-segments in each placeholder disappeared, and one of the placeholders changed in shape (from a circle to a square, or vice versa). Participants reported the orientation of the line segment in the uniquely shaped placeholder. The target–line segment was always oriented horizontally or vertically. Nontarget line segments were never oriented vertically or horizontally. In 66% of the trials, a distractor (identical to the regular placeholders) appeared simultaneously with the presentation of the target, at a random location midway between two regular placeholders. Distractor presence (absent/present) was fully randomized. After a correct or incorrect response, the fixation dot turned green or red, respectively.

The experiment consisted of two blocks (counterbalanced), which differed in response method. In the “keypress” condition, participants pressed the “Z” key to report a horizontal line segment and the “/” key to report a vertical line segment. In the “Mantra” condition, participants responded by moving their index fingers (see the following Apparatus, Software, and Response Collection section). In total, the experiment consisted of 40 practice trials and 480 experimental trials.

Paradigm, setup, and response collection in Experiment 2. a Participants reported the orientation of the line segment in the uniquely shaped placeholder. In the keypress condition, participants responded using a keyboard. b In the Mantra condition, participants responded by moving their index fingers, which were tracked using Mantra, quickly to the left or to the right. The camera pointed slightly downward toward the hand of the participant. Participants sat with their elbows resting on the table surfaces

Apparatus software, and response collection

The experiment was run on a laptop running Linux (Intel Pentium T4300, 2.1 Ghz, Ubuntu 9.10) and was written in Python. Mantra 0.2 was run on the same laptop. For image acquisition, a Logitech webcam was used, with a frame rate of 25 Hz and a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels. The webcam was mounted on top of the laptop display and pointed toward the participant in a slightly downward angle (Fig. 4b).

In the Mantra condition, participants wore a brightly colored paper fingercap on the index finger. To report a vertical line segment, participants made a rapid leftward movement with their index fingers. To report a horizontal line segment, participants made a rightward movement. For feedback purposes, movements were detected online using the standard Mantra movement detection algorithm. For the analysis, reaction time was determined offline using an interpolation script (included in Mantra), which estimates the exact moment at which a movement is initiated.

Results

Trials in which the RT was below 100 ms or above 1,200 ms were excluded (2.5%). In total, 97.5% of the trials were included in the analysis.

Separate, but identical, analyses were performed for the keypress and Mantra conditions. In the keypress condition, a two-tailed paired-samples t test revealed that RTs were higher in the distractor-present condition (M = 609 ms, SE = 46.1) than in the distractor-absent condition [M = 564 ms, SE = 49.6; t(3) = 3.5, p < .05; Fig. 5a]. In addition, for distractor-present trials, a repeated measures ANOVA was performed, using RT as a dependent variable and distractor-target separation (small, medium, or large) as an independent variable. There was a main effect of distractor–target separation, F(2, 6) = 14.1, p < .01 (Fig. 5b), so that there was more distractor interference if the distractor was close to the target.

Mean reaction times as a function of distractor presence (a) and distractor–target separation (b) in Experiment 2. Participants are slowed by the presence of a distractor (a; Theeuwes, 1994), and this effect is strongest if the distractor–target separation is small (Mathôt et al., 2010; Mounts, 2000). Importantly, the results in the keypress and Mantra conditions are qualitatively identical. Error bars represent 95% within-subjects confidence intervals (Cousineau, 2005)

The analysis for the Mantra condition revealed qualitatively identical results. A two-tailed paired-samples t test with movement-onset time as a dependent variable revealed an effect of distractor presence [present: M = 662 ms, SE = 33.4; absent: M = 634 ms, SE = 34.4; t(3) = 7.1, p < .01]. A repeated measures ANOVA with movement-onset time as a dependent variable revealed a main effect of distractor–target separation, F(2, 6) = 10.7, p < .05. All participants showed an effect of distractor presence as well as an effect of distractor–target separation, in both the Mantra and the keypress conditions. A two-tailed paired samples t test, with maximum movement velocity as a dependent variable, revealed no effect of distractor presence [present, M = 1.8 px/ms, SE = 0.34; absent, M = 1.8 px/ms, SE = 0.32; t(3) = 0.13, p = 0.9].

In order to investigate whether the level of noise was higher in the Mantra condition than in the keypress condition, we calculated the standard deviation of correct RTs in distractor-absent trials for each participant (using movement-onset time in the Mantra condition as the measure of RT). A paired samples t test revealed no difference in RT standard deviation between the keypress (M = 102.9) and Mantra [M = 100.0; t(3) = 0.1, p = .9] conditions in the distractor-absent trials. The difference in overall RT between the keypress (M = 593 ms) and Mantra (M = 653 ms) conditions did not reach significance, t(3) = 3.2, p = .28.

Discussion

In Experiment 2, we replicated two typical findings from an additional singleton paradigm. Participants were slowed by the presence of a distractor (Theeuwes, 1994), and this effect was more pronounced if the distractor was presented near the target (Mathôt et al., 2010; Mounts, 2000). Participants reported the orientation of a target line segment either by a keypress or by moving their index fingers in front of a camera. Both methods of response yielded quantitatively similar results. One difference is that the keypress data suggest that distractor interference is essentially equal for medium and large distractor–target separations. In contrast, the Mantra data suggest that distractor interference decreases gradually as a function of distractor–target separation, which is actually more in line with theory and findings on biased competition (Mounts, 2000).

Three important conclusions can be drawn from Experiment 2. First, the results clearly show that speeded responses can be registered precisely using Mantra. This may be surprising, given the fact that responses were collected using a webcam with a frame rate of only 25 Hz. Therefore, on any given trial, there was a maximum temporal resolution of 40 ms. However, this limited temporal resolution is only one of many sources of noise that contribute to the observed response times and are averaged out in the mean RTs. Empirically, we have shown that Mantra is a viable tool for collecting speeded responses, even when used in combination with a camera with a limited temporal resolution.

Second, the results of Experiment 2 show that Mantra can be used to address questions that cannot be resolved using keypress responses. Specifically, we have shown that the presence of a distractor delays the initiation of a movement, but does not interfere (or does very little) with speed of movement.

Third, we have shown that Mantra can be used in combination with Python. This is crucial, because Python is an open-source and platform-independent language, which makes it possible to use Mantra on different platforms and without the need for proprietary software.

Experiment 3

In Experiments 1 and 2, we showed that Mantra is a viable tool for response collection by demonstrating its use in realistic experimental settings. However, these experiments did not provide quantitative data on the precision of Mantra's measurements. Therefore, the aim of Experiment 3 was to quantify the precision with which Mantra is able to track a moving stimulus. We tracked a single stimulus that was attached via a mechanical arm to a computer-controlled wheel.

Method

Stimuli, apparatus, and procedure

We attached a small orange sticker to the end of a mechanical arm, which was attached to a computer-controlled wheel (see Fig. 6). Mantra ran on a netbook (Intel Atom, 1.66 GHz, Ubuntu 10.10) placed in front of the arm at a 40-cm distance. The built-in webcam, with a spatial resolution of 640 × 480 pixels and a temporal resolution of 40 ms, was used for tracking.

Experimental setup in Experiment 3. A stimulus, which was tracked by Mantra, was attached to a computer-controlled rotating arm. In the actual setup, the camera was positioned in front of the stimulus' rotational plane

The stimulus rotated in a continuous clockwise movement, describing a circular motion, with a radius of 9 cm, around the computer-controlled wheel. We increased the speed of the stimulus in nine steps, from 10.7 cm/s to 52.8 cm/s.

Data analysis

Although we did not know the true position of the stimulus at any given time, we knew that the stimulus described a circular motion. Therefore, we judged the measurement precision by quantifying how well the measured trajectory resembled a circular motion. More specifically, we knew that the x- and y-coordinates were described by sinusoidal functions. The measurement error was defined as the average absolute difference between the measured position of the stimulus and the position of the stimulus as predicted by the two (i.e., one for the x-coordinate and one for the y-coordinate) best-fitting sines. This analysis was performed separately for each speed level. No further statistics were performed, since the data are essentially descriptive.

Results and discussion

The measurement error varied from about 0.3° (2 mm) to 1.4° (10 mm; Fig. 7a). Precision was highest for intermediate stimulus velocities (22.1 cm/s to 48.6 cm/s).

The results clearly show that Mantra's spatial precision is high, up to 0.3° for intermediate velocities. The pronounced precision dip for low-stimulus velocities was unexpected. However, the reason for this anomaly becomes apparent when we inspect the unsmoothed data (Fig. 7b). For low-stimulus velocities, the weight of the stimulus slows the movement down when the stimulus is on the way up (i.e., the lower part of the curve is wider than the upper part of the curve), causing a small deviation from a perfectly circular movement, and thus confounding our measure of precision. This issue does not (or does very little) affect higher stimulus velocities (Fig. 7c, d), which therefore provide a better estimate of Mantra's precision. We conclude that Mantra is able to track stimuli with a spatial precision of up to 0.3°. This corresponds to a precision of up to 2 mm if the camera is positioned at 40 cm from the stimulus, which is a typical distance.

Results of Experiment 3. a The absolute measurement error of Mantra as a function of stimulus velocity. The spatial precision of Mantra varies from about 0.3° (2 mm) to 1.4° (10 mm). b The first 5 s of unsmoothed x-coordinate measurements in the 10.7 cm/s speed level (blue line). The orange line is the best fitting sine. c Same as (b), but for the y-coordinate in the 24.0 cm/s speed level. d Same as (b), but for the x-coordinate in the 52.8 cm/s speed level

Experiment 4

In Experiment 3, we could not directly compare the measured position of the tracked stimulus to its true position. Instead, we relied on an indirect measure: the assumption that the trajectory of the stimulus was, to a good approximation, circular.

Therefore, the aim of Experiment 4 was to extend the results of Experiment 3, using a paradigm in which the true position of the tracked stimuli is known. To this end, we tracked two stimuli that were presented on a computer display. The distance between the stimuli was varied and, after calibrating Mantra on a single stimulus configuration, we quantified the accuracy with which Mantra was able to measure the distance between the two stimuli.

Method

Stimulus, apparatus, and procedure

The experiment was run on a laptop running Linux (Intel Core i3-i370 m, 2.4 Ghz, Ubuntu 10.10) and was created in OpenSesame 0.22 (Mathôt & Theeuwes, 2010), using the Mantra Python bindings. Stimuli were presented on an external 19 in. TFT monitor, with a resolution of 1440 × 900 pixels. Mantra 0.3 was run on the same laptop. For image acquisition, a Trust Spotlight webcam was used, with a frame rate of 25 Hz and a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels. The webcam was placed in front of the external monitor, at a distance of 50 cm.

Two circles (r = 0.34°), one purple and one green, were presented against a gray background, and were tracked using Mantra. The distance between the stimuli was varied in 28 steps from 0.34° to 9.8°. In addition, the stimulus configuration was rotated around the center of the display in steps of 30° (angular). This way, stimuli were presented across the full field of view of the webcam, and distortions in the monitor as well as the webcam (such as pixels not being perfectly square), which are likely to affect measurements in a realistic experimental setting, were taken into account. 500 samples were recorded for each rotational step, yielding a total of 6000 samples for each distance.

Data analysis

We assumed that the real distance between the two stimuli was the raw distance measured by Mantra multiplied by a constant scaling factor. We calibrated Mantra (i.e., determined the scaling factor) on an intermediate distance (5.07°). Next, we compared how well the calibrated distance measured by Mantra matched the real distance between the two stimuli. We determined the accuracy when averaged over all samples (i.e., the average error) as well as the accuracy for single samples (i.e., the average absolute error). In addition, we determined the standard error of the measurement. These analyses were performed separately for each distance level. No further statistics were performed, since the data are essentially descriptive.

Results and discussion

The results are shown in Fig. 8 and, in more detail, in Table 1. Depending on the nature of an experiment, it is important to know the measurement accuracy averaged over a large number of samples (e.g., when you are tracking a slow moving or static stimulus) or to know the measurement accuracy for single samples (e.g., when you are tracking a fast moving stimulus).

Results of Experiment 4. a The distance between two stimuli as measured by Mantra, as a function of the real distance. b The average absolute measurement error, as a function of the real distance. A more detailed overview of this data is presented in Table 1

When looking at the average over 6,000 samples, measurement error ranged from 0.00060° (for the 0.34° distance) to 0.082° (for the 9.8° distance). For single samples, accuracy was also high, with an average absolute measurement error ranging from 0.0092° (for the 0.34° distance) to 0.12° (for the 9.8°) distance (Fig. 8b). This was also reflected by the standard error of the measurement, which ranged from 0.00015° (for the 0.33° distance) to 0.0014° (for the 9.8° distance). No anomalies occurred (such as tracking being lost or grossly inaccurate) during the entire session of 168,000 samples.

General discussion

In the present article, we have introduced Mantra, a system for object tracking. Mantra differs from existing object-tracking systems in three important respects. First, Mantra is freely available under an open-source license. Second, Mantra does not require expensive dedicated hardware. A computer and a camera (we used ordinary webcams for our experiments) are all that is needed to run Mantra. Third, Mantra is designed specifically as a tool for experimental psychology. Therefore, Mantra integrates well with E-Prime and Python. Mantra can be used from within other programming languages as well, provided that they have basic networking capabilities. This requires some additional coding for which the E-Prime and Python libraries can be used as templates.

In Experiment 1, we validated the spatial precision of Mantra in a realistic experimental setting, by replicating the Müller-Lyer (1889) illusion. In this experiment, participants matched two line segments surrounded by inward- or outward-pointing arrowheads. Participants manipulated the length of one of the line segments by changing the distance between their thumbs and index fingers, which were tracked using Mantra. In Experiment 2, we validated the temporal precision of Mantra by using a variant of the additional singleton paradigm (Theeuwes, 1994). In this experiment. participants reported the orientation of a target line segment. In one condition, participants responded using a keyboard. In another condition, they responded by moving their index fingers, which were tracked using Mantra. Crucially, both methods of response yielded very similar results, and there was no evidence for an increased level of noise when responses were collected using Mantra. In Experiments 3 and 4, we investigated the spatial precision and accuracy of Mantra more rigorously by tracking a computer-controlled physical stimulus and stimuli presented on a computer display. These experiments showed that under optimal conditions (i.e., tracking an artificial stimulus on a computer display), it is possible to track stimuli with a measurement error of less than 0.1°. Perhaps more realistically, under good conditions (i.e., tracking a properly defined physical stimulus), it is feasible to track stimuli with a spatial precision of up to 0.3°, which corresponds to about 2 mm in a typical experimental setup.

In summary, Mantra is a basic, but reliable and accurate, object-tracking system. Mantra is freely available and has been designed specifically for use in psychological experiments. Because Mantra requires only a computer and a camera, it is possible to create a highly mobile experimental setup. Mantra is unique in that it makes object tracking accessible and easy to use for everyone.

References

Brenner, E., & Smeets, J. B. J. (1996). Size illusion influences how we lift but not how we grasp an object. Experimental Brain Research, 111, 473–476.

Cousineau, D. (2005). Confidence intervals in within-subject designs: A simpler solution to Loftus and Masson’s method. Tutorial in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 1, 4–45.

Donders, F. C. (1969). On the speed of mental processes. Acta Psychologica, 30, 412–431.

Geller, A. S., Schleifer, I. K., Sederberg, P. B., Jacobs, J., & Kahana, M. J. (2007). PyEPL: A cross-platform experiment-programming library. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 950–958.

Goodale, M. A., & Milner, A. D. (1992). Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends in Neurosciences, 15, 20–26.

Mathôt, S., & Theeuwes, J. (2010). OpenSesame (Version 0.22) [Computer software and manual]. Retrieved from http://www.cogsci.nl/opensesame

Mathôt, S., Hickey, C., & Theeuwes, J. (2010). From reorienting of attention to biased competition: Evidence from hemifield effects. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72, 651–657.

Mounts, J. R. W. (2000). Attentional capture by abrupt onsets and feature singletons produces inhibitory surrounds. Perception & Psychophysics, 62, 1485–1493.

Müller-Lyer, F. C. (1889). Optische urteilstäuschungen. Archiv für Anatomie und Physiologie, Physiologische Abteilung, 2, 263–270.

Peirce, J. W. (2007). PsychoPy—Psychophysics software in Python. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 162, 8–13.

Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32, 3–25.

Schneider, W., Eschman, A., & Zuccolotto, A. (2002). E-Prime reference guide. Psychology Software Tools, Inc.

Theeuwes, J. (1994). Stimulus-driven capture and attentional set: Selective search for color and visual abrupt onsets. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20, 799–799.

Tipper, S. P., Howard, L. A., & Jackson, S. R. (1997). Selective reaching to grasp: Evidence for distractor interference effects. Visual Cognition, 4, 1–38.

Author Note

This research was funded by a grant from NWO (Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research), Grant 463-06-014, to J. T.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mathôt, S., Theeuwes, J. Mantra: an open method for object and movement tracking. Behav Res 43, 1182–1193 (2011). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0105-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0105-9