Abstract

It is now well established that people in conversations repeat each other’s words and structures. Does doing so reflect dialogue participants’ expectations that their own choices of words or structures will be repeated back to them? In two experiments, subjects and confederates (purportedly) took turns describing pictures to each other. On critical trials, we measured response latencies to choose pictures when labels (e.g., stroller) or syntactic structures (a prepositional dative) that subjects had just produced were repeated back to them, versus when they heard reasonable alternatives (baby carriage or a double-object structure). Experiment 1 showed that repeated words and syntactic structures both elicit faster responses. Experiment 2 showed that the effect happens even when subjects hear descriptions from computers, instead of from their addressees, and that the repeated-word effect was not due to preferences for labels. These observations suggest that dialogue participants expect their own word and structure choices to be repeated back to them, and this is general to the task situation rather than specific to their communicative partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Do priming effects in dialogue reflect partner- or task-based expectations?

People in conversations repeat each other's words and structures. If one person calls an infant conveyance “stroller” (rather than “baby carriage”), a conversational partner is likely to describe the same referent also as a “stroller” (Brennan & Clark, 1996). Analogously, if one person describes a situation with a prepositional dative structure (“The student gave [an apple] [to the teacher]”) rather than a double-object structure (“The student gave [her teacher] [an apple]”), a conversational partner is likely to also describe a similar situation with a prepositional dative (“The helper gave [a hammer] [to the carpenter]”) (Branigan, Pickering, & Cleland, 2000). The question we ask is how such repetition might benefit communication.

The repetition of words has largely been explored within collaborative approaches to language use (Clark, 1996). Much of this research has shown that repetition provides a communicative benefit across a task. For example, speakers repeat descriptions as they perform tasks, and the more they do so, the faster they accomplish those tasks (e.g., Clark & Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986). People repeat descriptions more to the same partner (Brennan & Clark, 1996), and comprehenders are sensitive to when prior partners repeat descriptions (Brown-Schmidt, 2009; Metzing & Brennan, 2003).

Much research has investigated people’s tendency to repeat sentence structures, often called syntactic priming (for a review, see Pickering & Ferreira, 2008). The basic effect is that speakers produce structures they have just heard or said (Bock, 1986; Branigan, et al., 2000). Comprehenders too are sensitive to syntactic repetition, in that they anticipate that sentences will have structures like those recently heard (Arai, van Gompel, & Scheepers, 2007; Branigan, Pickering, & McLean, 2005; Thothathiri & Snedeker, 2008), and they adapt to structures across an experiment (Fine, Qian, Jaeger, & Jacobs, 2010). Syntactic repetition effects have also been revealed in relatively more natural language situations recorded in language corpora (e.g., Reitter, Moore, & Keller, 2006).

In sum, speakers repeat words and structures, and comprehenders are faster to comprehend repeated words or structures. Such repetition can provide benefits to the communicative process in multiple ways, including by signaling conceptual pacts (Brennan & Clark, 1996; Clark, 1996), or because longer-term repetition of words and structures may improve overall performance of a task (Reitter & Moore, 2007). Here, we determine whether repetition provides a lower-level processing benefit that we cast in terms of the language comprehension system forming expectations that speakers will repeat words and structures. Specifically, given that speakers actually repeat words and structures more than chance, expectations of repetition will often be correct, which will allow comprehension mechanisms to efficiently deploy processing resources (Fine & Jaeger, in press). Expecting repetition is useful even when proven incorrect, because failed expectation indicates informative material or an opportunity to learn about the language (Chang, Dell, & Bock, 2006; Fine & Jaeger, in press; Kraljic & Samuel, 2006), conversational partners, situations, or contexts.

Note that here, expectations are representations of the language processing system’s best estimate of the features of upcoming language, allowing for efficient resource deployment or learning (as opposed to a more colloquial definition of expectations, such as an expectation that a British speaker will call a stroller “pram”). Priming—the better processing of stimuli that are similar to previously processed stimuli—can be one mechanism that drives expectation, although expectations can come from other processing influences as well.

The present experiments were designed to explore two questions about the expectations the comprehension system might form. First, can expectations for repetition be formed interactively, from comprehenders’ acts of production to their subsequent comprehension? Put somewhat differently, do people expect to prime their conversational partners? Thus far, repetition effects on comprehension have only been shown to be “one-way,” from one heard sentence to the next. The possibility that comprehenders expect their own production choices to be repeated back would allow expectation benefits to accrue across conversational participants. To assess this, the experiments below measured whether comprehenders would understand utterances faster when they did versus did not repeat the comprehenders’ own choices of words and structures in an interactive task. (Branigan et al., 2005, showed that comprehenders tend to interpret ambiguous sentences as having the same structures as they produced, although, unlike here, comprehenders did not choose their own structures.)

Second, if comprehenders expect their choices of words and structures to be repeated back to them, to what is the expectation attributed? One possibility is that comprehenders form expectations about their specific conversational partners. That is, it may be that because comprehenders know that their conversational partners understood a word or structure, they expect that same word or structure back. Alternatively, the effect may be across-the-board, if the comprehension system forms expectations in general that allow it to prepare (and so more quickly process) repetitions of just-produced utterances, irrespective of who (or what) those repetitions come from. To assess this, we tested whether comprehenders would understand utterances faster if they repeated the comprehenders’ choices of words or structures even when those repeated utterances were not produced by the comprehenders’ conversational partners.

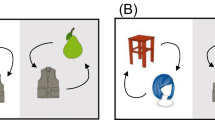

The basic task involved a subject and a confederate as communicative partners, taking turns describing simple line-drawn pictures to one another. We designed two types of trials. On critical lexical trials, the subject first saw a line-drawn object that allowed more than one description, which he or she described how he or she wished (e.g., “stroller”) so that (purportedly) the partner could choose it from two he or she could see. Then, the subject heard the partner describe that same object either with the same label (“stroller”) or with the alternative (“baby carriage”). The onset of the partner’s description triggered the appearance of two pictures on the subject’s screen, one of which fit the description; the subject chose this object as quickly and accurately as possible. Critical syntactic trials proceeded analogously, except with scenes that allowed either prepositional dative or double-object descriptions (e.g., “The cowboy is showing [the gun] [to the sailor]”). Note that unlike on word trials, the first and second scenes had different participants, although the two scenes shared an action (and were thus described with the same verb). If comprehenders form expectations that their own words and structures will be repeated back to them, then subjects should choose described objects and scenes faster when hearing descriptions or structures they just used, as compared with when hearing alternative descriptions or structures.

Experiment 1 implemented this basic paradigm using a subject and an experimental confederate. Experiment 2 assessed whether any expectations are formed about comprehenders’ conversational partners specifically, or whether they are general to the task or situation, by having subjects direct utterances to the experimenter but then hear prerecorded utterances presented from a computer speaker.

Experiment 1

Method

Subjects

Forty-eight native English-speaking students at the University of California, San Diego participated for course credit.

Materials

Each trial involved three pictures (a prime, target, and foil). Pictures for lexical trials were selected from the International Picture Naming Project database (Bates et al., 2003). We selected 27 that had at least two labels, and asked 37 separate volunteers to generate a label for each. From these, we selected 24 critical targets. Another 48 pictures were used as fillers.

The 24 syntactic target pictures depicted an agent transferring an object to a patient (e.g., a burglar, banana, and sailor). A dative verb (e.g., GIVE) was printed at the bottom of each. We created prime and foil pictures for each target. Primes and foils had the same verb as the target; foils (but not primes) additionally had the same agent, to ensure subjects could not select the correct target picture upon hearing the agent and verb. We also created 24 fillers, each labeled with a nondative verb. These varied as to whether prime and foil shared the verb and agent with the target (8), shared only the agent (3), or were fully distinct (13).

Procedure

Figure 1 illustrates the procedure. Subjects were paired with a confederate. Pairs sat at opposite ends of a table, each in front of a computer and microphone. A digital audio recorder recorded the interaction. Participants alternated being speaker and addressee. On each trial, the speaker described the picture displayed on his or her computer, and the addressee selected that picture from two pictures displayed on his or her own computer. Then they switched roles.

After four practice trials, the subject was assigned seemingly randomly to the role of speaker for the first turn. The prime appeared on the subject’s computer. He or she produced a description and then pressed a button to end the turn as speaker. The subject’s computer screen remained blank until the confederate (now the speaker) began speaking. The confederate’s microphone activated a voice key that caused two pictures to be displayed on the subject’s computer. One of these fit the confederate’s description; the subject pressed a button to indicate which. A 1,000-ms delay preceded the next trial.

Unbeknownst to the subject, as the subject described a picture, the confederate’s computer displayed two possible descriptions the subject might generate. The confederate pressed a button to record which the subject had produced (or a third button labeled “Other”). On the next turn, when the confederate was ostensibly generating picture descriptions, the computer displayed the confederate’s description (see Fig. 1). The syntactic block worked analogously. Order of blocks was counterbalanced. Trials were pseudorandomly ordered such that there were no more than three consecutive critical or filler trials.

Results and discussion

Subjects produced 2,304 critical descriptions, of which 88.3% (2,035) were analyzed. Trials were excluded because the voice key failed to detect the confederate’s voice (16) or because the subject produced other descriptions (124), selected the wrong picture (58), or had a mean reaction time (RT) 2.5 standard deviations larger than his or her mean task RT (74). (Note that some trials violated multiple exclusion criteria.) Results were similar with log transformed RTs (any numerical differences were larger with log RTs). Syntactic descriptions were strictly coded for structure; lexical content was not evaluated. Subject and item means were analyzed with one-way repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with the factor repetition (repeated, new), separately for each task. Significant effects achieved the .05 level. Variability is reported with 95% confidence intervals (Loftus & Masson, 1994). One syntactic target was lost due to a coding error.

Subjects’ mean RTs to select pictures as a function of task and repetition are shown in Fig. 2. For lexical trials, subjects were 170 ms faster to select a picture if it had the same description the subject had just used (772 ms) than if it had a different description (942 ms), a significant difference, F 1(1, 47) = 96.7, CI = ±35 ms; F 2(1, 23) = 72.1, CI = ±42 ms. For syntactic trials, subjects were 103 ms faster to select a picture if it was described with a sentence that had the same syntactic structure as the one the subject had just used (2,703 ms) than if it had a different syntactic structure (2,806 ms), also a significant difference, F 1(1, 47) = 17.8, CI = ±49 ms; F 2(1, 22) = 8.57, CI = ±68 ms. Thus, subjects showed repetition benefits for both repeated descriptions and repeated syntactic structures. This suggests that comprehenders form expectations that they will hear their own choices of words or structures produced back to them.

In the task, to enact a communicative act, subjects chose the prime’s form. This feature raises a concern, however. Subjects might choose labels or structures because they prefer them, and they may comprehend preferred labels and structures faster. For word trials, the pictures subjects described on prime events were identical to the chosen targets, so object-specific preferences may operate; Experiment 2 assesses this point directly. But for syntactic trials, the pictures subjects described on prime events and then heard described on target events were different. Thus, because a subject used, say, a prepositional dative on a prime trial does not mean that he or she would also prefer a prepositional dative for the different picture on the target trial.

However, it may be that subjects have overall preferences for prepositional dative or double-object structures. Also, prime and target events shared a verb, and specific verbs may prefer prepositional dative or double object structures. Either of these might cause the observed difference shown in Fig. 2. The analyses reported in Fig. 3 assess these possibilities. The ordinates of each graph plot how much faster responses to prepositional datives were than responses to double objects. The top graph shows this prepositional dative advantage for each subject as a function of that subject’s overall preference for prepositional datives, and the bottom graph for each verb as a function of that verb’s overall preference for prepositional datives (plotted on each abscissa). There is no appreciable tendency for prepositional datives to be comprehended faster by subjects who say prepositional datives more or for prepositional datives to be comprehended faster when they include verbs that were produced with prepositional datives more. Thus, for syntactic structures at least, the observed difference is likely due to repetition.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 had two objectives. First, comprehenders may have responded faster in Experiment 1 because they expected their dialogue partner specifically to repeat their words and structures or because they expected words and structures to be repeated more generally, perhaps as tied to the overall task context. In Experiment 2, target descriptions were prerecorded and presented through a computer speaker rather than from subjects’ dialogue partners. If repetition benefits are observed, these cannot be based on expectations of partner behavior specifically.

Second, the word repetition benefit observed in Experiment 1 may have been due to subjects’ preferences for particular labels for particular objects. In Experiment 2, subjects named every object in isolation on one week. They then returned the next week and heard objects described with their chosen (presumably preferred) label or the alternative. Preference effects should be evident to the extent that subjects are faster to choose objects labeled with their (week-ago) chosen label, rather than with an alternative label.

Method

Subjects

Forty-eight native English-speaking students at the University of California, San Diego participated for course credit.

Procedure

All subjects completed two experimental sessions separated by 1 week. In Session 1, subjects’ preferred picture names were determined. Subjects saw and named every picture they were to see in Session 2, pressing a button to advance pictures. Responses were recorded and coded.

Half of Session 2 trials, priming trials, were like the prime–target trials in Experiment 1, except that subjects directed prime descriptions to the experimenter (who coded the description, although subjects were not told this), and all target descriptions were prerecorded and presented aloud from an external speaker connected to the computer. On the other half of Session 2 trials, preference trials, the prime was skipped; subjects saw only a target picture and heard a computer description, which was the same as or the alternative to the description the subject had provided for that picture in Session 1. Benefit type (priming, preference) and repetition (repeated, new) were manipulated in counterbalanced fashion across subjects and pictures. Lexical versus syntactic trials were blocked (order-counterbalanced); benefit type was not. Subjects’ RTs were measured from the onset of the computer description, which coincided with the onset of the pictures on subjects’ screens.

Results and discussion

Subjects provided 2,304 critical Session-2 responses, of which 92% (2,114) were analyzed. Trials were excluded because the subject produced an other description in Session 1 (80) or Session 2 (46), selected the wrong picture (22), or had an RT 2.5 standard deviations larger than his or her mean RT in that task (46). Another five trials were lost due to computer error. One subject’s syntactic trials were removed because exclusions yielded an empty cell. Subject and item means were submitted to two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs with the factors benefit type (priming, preference) and repetition (repeated, new) for each task.

Figure 4 plots RTs for repeated and new descriptions on priming and preference trials separately for each task. For lexical trials, subjects showed a robust priming benefit but no preference benefit. The main effect of benefit type was significant, F 1(1, 47) = 36.2, CI = ±23 ms, F 2(1, 23) = 9.2, CI = ±46 ms, as were the main effect of repetition, F 1(1, 47) = 112, CI = ±20 ms, F 2(1, 23) = 24, CI = ±44 ms, and the interaction, F 1(1, 47) = 48.9, CI = ±30 ms, F 2(1, 23) = 47.7, CI = ±35 ms. The 30-ms preference effect was not significant, F 1(1, 47) = 3.79, p < .06, F 2(1, 23) = 1.58, whereas the 180 -ms repetition benefit was, F 1(1, 47) = 140, F 2(1, 23) = 121. For syntactic trials, subjects showed both a preference and a priming benefit. The main effect of benefit type was not significant, F 1(1, 46) = 1.22, CI = ±49 ms, F 2(1, 23) = 3.39, p < .08, CI = ±36 ms, whereas the main effect of repetition was, F 1(1, 46) = 53.2, CI = ±44 ms, F 2(1, 23) = 32.6, CI = ±58 ms; the interaction was not significant by subjects, F 1(1, 46) = 2.69, CI = ±63 ms, F 2(1, 23) = 7.19, p < .05, CI = ±47 ms. The 122-ms preference effect was significant, F 1(1, 46) = 15.0, F 2(1, 23) = 26.5, as was the 195-ms repetition benefit, F 1(1, 46) = 38.3, F 2(1, 23) = 80.0.

Time to select a described picture when its label (left graph) or syntactic structure (right graph) did or did not repeat subjects’ own descriptions from the preceding week (preference trials) or the preceding trial (priming trials). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals by subjects based on ANOVA output

Thus, with both lexical and syntactic repetition, benefits were observed from computer descriptions. These results show that comprehenders’ expectations for repetition are not tied specifically to comprehenders’ dialogue partners. Instead, comprehenders’ expectations are likely more general, tied to the overall task situation.

Furthermore, the lexical repetition benefit is not due to subjects’ preferences. If subjects called a picture “stroller” in Session 1, they were only 30 ms faster to respond to “stroller” than to “baby carriage” in Session 2. But if they called a picture “stroller” on a prime trial, they were subsequently 180 ms faster to respond to “stroller” than to “baby carriage.”

Syntactic trials revealed independent preference and priming benefits. If subjects described a picture with a prepositional dative in Session 1, they were 122 ms faster to respond to a prepositional dative (rather than a double-object) description of that picture in Session 2. (Note that unlike in Experiment 1, this reflects a preference to describe a particular picture in a specific way, rather than reflecting any subject- or verb-specific preference.) Independently, if subjects described one picture with a prepositional dative on a prime trial, they chose a different picture 195 ms faster if it was described with a prepositional dative rather than a double-object structure.

General discussion

These experiments show that (1) subjects understand words or structures they just said faster than reasonable alternatives; (2) this repetition benefit is not due to subjects’ (or, for structures, verbs’) preferences for those words or structures; and (3) this repetition benefit operates partner-independently. Such repetition benefits can be construed as reflecting expectations for repeated words and structures; within this framework, these observations suggest that subjects have relatively general expectations that their own choices of words and structures will be repeated back to them.

The differences observed due to lexical repetition here have been interpreted as facilitation. Equally, they could reflect interference, because comprehenders may respond more slowly when their choices of labels are not repeated. This is consistent with the claim that performance in the lexical condition is due to conceptual pacts (Brennan & Clark, 1996). Two considerations urge caution, however. First, note that in Experiment 2, subjects were no slower after immediate nonrepetition than in either preference condition when there were no priming utterances at all; if the preference conditions are considered baseline, this suggests faster responding in the repeated condition rather than slower responding in the alternative condition. Second, Experiment 2 shows that effects are not partner specific (although note the caveat described next), whereas conceptual pacts have been shown to be partner specific (Brennan & Clark, 1996; Metzing & Brennan, 2003). Likely, the benefits observed here are different from those observed in tasks that encourage conceptual pacts.

Of course, the claimed partner independence observed in Experiment 2 may, instead, be due to other factors. An intriguing possibility comes from observations that sometimes, people treat computers as social agents (Nass, Steuer, Tauber, & Reeder, 1993). In Experiment 2, this may have led subjects to treat the computer that was part of the experimental apparatus as an overhearer to which they attributed an expectation of repetition. Alternatively, subjects may have linked the experimenter’s utterance coding to the repeated or alternative labels heard from the computer (although subjects and experimenters used separate computers).

The results observed here are consistent with interactive alignment models (e.g., Pickering & Garrod, 2004). These claim that priming from repetition yields communicative benefits because priming accrues not only to individual representations, but to links from one representational level to another (including representations of interpretations). This predicts benefits from production to comprehension in an automatic, across-the-board fashion, as observed here.

References

Arai, M., van Gompel, R. P. G., & Scheepers, C. (2007). Priming ditransitive structures in comprehension. Cognitive Psychology, 54, 218–250.

Bates, E., D'Amico, S., Jacobsen, T., Szekely, A., Andonova, E., Devescovi, A., . . . Tzeng, O. (2003). Timed picture naming in seven languages. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10, 344–380

Bock, J. K. (1986). Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology, 18, 355–387.

Branigan, H. P., Pickering, M. J., & Cleland, A. A. (2000). Syntactic co-ordination in dialogue. Cognition, 75, B13–B25.

Branigan, H. P., Pickering, M. J., & McLean, J. F. (2005). Priming prepositional phrase attachment during comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 31, 468–481.

Brennan, S. E., & Clark, H. H. (1996). Conceptual pacts and lexical choice in conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 22, 1482–1493.

Brown-Schmidt, S. (2009). Partner-specific interpretation of maintained referential precedents during interactive dialog. Journal of Memory and Language, 61, 171–190.

Chang, F., Dell, G. S., & Bock, K. (2006). Becoming syntactic. Psychological Review, 113, 234–272.

Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, H. H., & Wilkes-Gibbs, D. (1986). Referring as a collaborative process. Cognition, 22, 1–39.

Fine, A. B., & Jaeger, T. F. (in press). Evidence for implicit learning in syntactic comprehension. Cognitive Science.

Fine, A. B., Qian, T., Jaeger, T. F., & Jacobs, R. A. (2010). Is there syntactic adaptation in language comprehension? Paper presented at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Workshop on Cognitive Modeling and Computational Linguistics, Uppsala, Sweden

Kraljic, T., & Samuel, A. G. (2006). How general is perceptual learning for speech? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 262–268.

Loftus, G. R., & Masson, M. E. J. (1994). Using confidence intervals in within-subject designs. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 1, 476–490.

Metzing, C., & Brennan, S. E. (2003). When conceptual pacts are broken: Partner-specific effects on the comprehension of referring expressions. Journal of Memory and Language, 49, 201–213.

Nass, C., Steuer, J., Tauber, E., & Reeder, H. (1993, April). Anthropomorphism, agency, and ethopoea: Computers as social actors. Paper presented at the InterCHI '93, Amsterdam.

Pickering, M. J., & Ferreira, V. S. (2008). Structural priming: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 427–459.

Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2004). Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 169–226.

Reitter, D., & Moore, J. D. (2007, June). Predicting success in dialogue. Paper presented at the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association of Computational Linguistics (ACL), Prague, Czech Republic.

Reitter, D., Moore, J. D., & Keller, F. (2006, July). Priming of syntactic rules in task-oriented dialogue and spontaneous conversation. Paper presented at the 28th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Vancouver, Canada.

Thothathiri, M., & Snedeker, J. (2008). Give and take: Syntactic priming during spoken language comprehension. Cognition, 108, 51–68.

Author Note

This material is based upon work supported by the NIH under Grant Numbers F32 HD052342 and R01 HD051030. We thank Stephanie Ang, Lisa Graves, Paige Heath, Janet Park, and Katyrose Reed for their assistance with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira, V.S., Kleinman, D., Kraljic, T. et al. Do priming effects in dialogue reflect partner- or task-based expectations?. Psychon Bull Rev 19, 309–316 (2012). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-011-0191-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-011-0191-9