Published online Sep 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i36.10480

Peer-review started: January 21, 2015

First decision: April 13, 2015

Revised: April 22, 2015

Accepted: July 3, 2015

Article in press: July 3, 2015

Published online: September 28, 2015

Small bowel volvulus, which is torsion of the small bowel and its mesentery, is a medical emergency, and is categorized as primary or secondary type. Primary type often occurs without any apparent intrinsic anatomical anomalies, while the secondary type is common clinically and could be caused by numerous factors including postoperative adhesions, intestinal diverticulum, and/or tumors. Here, we report a rare case of a 60-year-old man diagnosed with small bowel volvulus using multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) angiography. Further discovery by laparotomy showed one jejunal diverticulum, longer corresponding mesentery with a narrower insertion, and a lack of mesenteric fat. This case report includes several etiological factors of small bowel volvulus, and we discuss the possible cause of small bowel volvulus in this patient. We also highlight the importance of MDCT angiography in the diagnosis of volvulus and share our experience in treating this disease.

Core tip: We present a case report of a patient diagnosed with small bowel volvulus using multidetector computed tomography angiography. Further discovery by laparotomy showed one jejunal diverticulum, longer corresponding mesentery with a narrower insertion, and a lack of mesenteric fat. We discussed the possible cause of small bowel volvulus, and demonstrated the surgical skills in treating chronic small bowel volvulus.

- Citation: Shen XF, Guan WX, Cao K, Wang H, Du JF. Small bowel volvulus with jejunal diverticulum: Primary or secondary? World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(36): 10480-10484

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i36/10480.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i36.10480

Small bowel volvulus involves torsion of all or a large segment of the small intestine and its mesentery[1]. Most patients with acute small bowel volvulus attend hospital with a complication of intestinal obstruction, while those with chronic small bowel volvulus often present atypical symptoms. Thus, better understanding of the etiology of midgut volvulus, as well as relative instrumental examination, may help improve the diagnosis and treatment of this disease. Small bowel volvulus can be categorized as primary (no obvious predisposing factors) or secondary (specific predisposing anatomical abnormalities)[2]. Numerous etiological factors have been suggested to contribute to the process of primary small bowel volvulus, while adhesion bands, pregnancy, jejunal diverticulum[1,3] and/or complications following laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC)[4] are the underlying causes of the secondary type. Here, we describe a patient with small bowel volvulus who had only one jejunal diverticulum, and underwent LC during the process of small bowel volvulus. We also further discuss the possible causes of the midgut volvulus in this patient.

A 60-year-old man presented to our department with a 2-year history of increasingly intermittent upper abdominal pin-prick pain, which occurred after meals, lasted 2-4 h, and eased in the right lateral decubitus. He denied any presence of other gastrointestinal symptoms, or change in bowel or bladder habits. He was not admitted to hospital nor did he receive any medical treatment during the first year until diagnosis of cholecystolithiasis, which allowed him to receive LC. There was no other relevant past medical, family or surgical histories. Upper abdominal deep tenderness was found on physical examination.

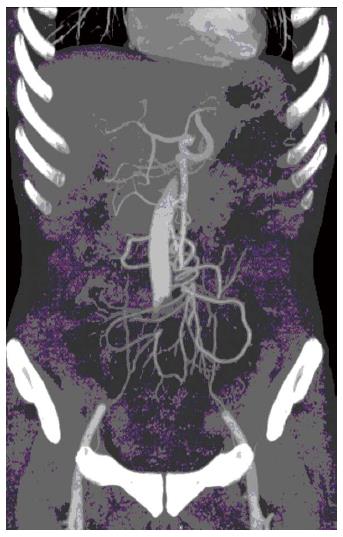

The initial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed the mesenteric artery and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) with “whirl signs”[5,6] (Figure 1). The portal venous phase axial CT images showed that the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and SMA had a normal relation, and the duodenum was identified behind the root of the SMA. To clarify small bowel volvulus, the patient was also referred for multidetector CT (MDCT) angiography due to suspicion of vascular variation that could also have accounted for his intermittent upper abdominal pain. On MDCT angiography, the twisted small vessels arising from the distal SMA could be seen, with no relevant primary vascular stenosis or occlusion (Figure 2). Tightly twisted mesentery around the point of torsion was also discovered. It is notable that no evidence of bowel infarction and/or ischemia was detected, as well as small bowel diverticulum.

The patient underwent laparotomy on day 4 of hospitalization after excluding surgical contraindications, although there were no positive abdominal physical signs except for upper abdominal deep tenderness. Laparotomy through an upper midline incision revealed strangulation of the small intestine and massive bloody ascites. The strangulation was caused by 540 degree clockwise mesenteroaxic torsion. Reduction of the torsion demonstrated strangulation of the intestine at Treitz ligament 30 cm from distal jejunum to small intestine of 200 cm. We also discovered one jejunal diverticulum (Figure 3) and fibrous adhesion among the strangulated intestine mesentery, which may have been caused by previous LC and inflammation induced by jejunal diverticulum. There were no ischemic changes or necrosis, thus, we performed de-torsion of the small bowel volvulus and small bowel arrangement to prevent re-torsion. The patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery and was discharged on postoperative day 7.

Volvulus is a well-established cause of acute intestinal obstruction that occurs most frequently in the sigmoid colon, followed by other areas of the colon. Volvulus of the small intestine is usually found in the neonatal period and diagnosed in the first week of life, and 80% within the first month, and is rare among adults[7]. Small bowel volvulus can be categorized as primary or secondary. Primary small bowel volvulus with no congenital malrotation, bands, or postoperative adhesions is one of the more common surgical emergencies in the adult populations of India, Central Africa, and the Middle East, with less occurrence among western populations[2,8]. Several etiological factors are suggested to contribute to primary small bowel volvulus, including absence of food during daylight hours and consumption of a single, large, high-fiber meal at night[8]. In the Chinese literature, no particular dietary factors are highlighted. Longer corresponding mesentery with a narrower insertion and a lack of mesenteric fat, as well as large volume of air in the intestine, also account for the process of primary small bowel volvulus[9]. In contrast, secondary small bowel volvulus often occurs in older patients, with both sexes affected equally. When analyzing the causes of the secondary type, postoperative adhesions, which may interrupt intestine location and arrangement, have been of central importance[1]. However, many other causes have been reported, including tumors, Meckel’s diverticulum, pregnancy, hematoma, and complications following LC. In the present case, we found one jejunal diverticulum and fibrous adhesions between the mesentery. This patient had a history of LC, therefore, the fibrous adhesions mentioned above may have been due to surgery and/or inflammation induced by jejunal diverticulum. Although both these factors have been suggested as the cause of small bowel volvulus, we discovered a longer corresponding mesentery with a narrower insertion during surgery. We think that the single diverticulum may have been the secondary cause for initiation of volvulus because this diverticulum was < 3 cm and not large enough to trigger small bowel twisting and hampering its repositioning. Because our patient underwent LC 1 year after his upper abdominal pain, fibrous adhesions may also have been the secondary cause of small bowel volvulus. Consequently, it is difficult to identify the exact category as primary or secondary small bowel volvulus for this patient. We have presented a case of small bowel volvulus with jejunal diverticulum and a history of LC during the process of volvulus.

Clinical presentation of midgut volvulus is usually nonspecific unless an acute small bowel obstruction with signs of peritonitis and/or systemic inflammatory responses occurs[8]. We should raise suspicion for small bowel volvulus when a patient displays symptoms such as upper abdominal pain after meals, alternating diarrhea and constipation, tenderness and weight loss[10]. Accessory examination, especially for CT and angiography, improves preoperative diagnostic accuracy[11]. CT scans demonstrate signs of volvulus (known as “whirl signs”), signs of intestinal ischemia (thickening of the bowel wall and free peritoneal fluid), and signs of complete small bowel obstruction (air-filled bowel loops or dilatation of closed intestines)[12]. The sensitivity of CT for diagnosis of midgut volvulus is 60%[13]. Angiographic appearances of the twisted mesenteric vessels, dilated SMV, or prolonged contrast transit time also suggest midgut volvulus[14]. However, angiography may be time-consuming and invasive, limiting its use under emergency conditions. In the presented case, we used CT together with MDCT angiography, which produced multiplanar 3D images, which provided information about the presence of the volvulus, as well as the degree and location of intestinal obstruction, to make the preoperative diagnosis of small bowel volvulus[15]. We clearly saw the whirl sign and the small bowel wrapping around the SMA.

Proper preoperative management and early surgical treatment are essential for small bowel volvulus[2]. De-torsion of the involved bowel is needed when the intestine is viable. To avoid recurrence of the volvulus, intestinal fixation or appropriate resection of the intestine may also be conducted[16]. The volvulus in this case may have mainly been due to the longer corresponding mesentery with a narrower insertion and lack of mesenteric fat. Therefore, we first untwisted the volvulus, lysed the fibrous adhesions, removed the jejunal diverticulum, and finally rearranged the entire small intestine (Figure 4).

We performed intestinal arrangement (extra-intestinal arrangement) as follows: the arrangement started at jejunum 15 cm from Treitz ligament and ended at ileum 20 cm from ileocecus. The fold was made in intestine every 15 to 25 cm, and 4-0 silk was used to suture small intestinal mesenteries every 1.5 to 2 cm. It is notable that 4 cm intestinal segment which consists of the fold should not be fixed or sutured, and the sutured intestine should also be fixed in the retroperitoneum while not in the side peritoneum so as to alleviate postoperative pain as splanchnic nerves control the retroperitoneum. The gap between sutured mesentery and intestine should be 2-3 cm as well.

In summary, we presented a case of small bowel volvulus that may possibly be categorized as primary type. Although one jejunal diverticulum and the adhesion band between mesenteries have been found at laparotomy, a longer corresponding mesentery with a narrower insertion and lack of mesenteric fat may have been the main cause in our case. When a patient with small bowel volvulus is asymptomatic, CT and MDCT angiography may be helpful for accurate and immediate diagnosis because they can demonstrate the rotated small bowel and mesentery, providing simultaneously, information for any associated intestinal ischemia. Surgical intervention is necessary for the treatment of midgut volvulus.

A 60-year-old man with a 2-year history of increasingly intermittent upper abdominal pin-prick pain, which occurred after meals, lasted 2-4 h, and eased in the right lateral decubitus.

Upper abdominal deep tenderness was found on physical examination.

Superior mesenteric artery embolus and intestinal intussusception.

No special laboratory abnormality was found in this patient despite a low BMI (17.5 kg/m2).

Computed tomography (CT) together with multidetector CT (MDCT) angiography was performed for preoperative diagnosis, and the whirl sign, as well as the small bowel wrapping around the superior mesenteric artery, was shown.

No pathological diagnosis was available for this patient.

Surgery was performed in this patient, and the specific procedures were to untwist the volvulus, lyse the fibrous adhesions, remove the jejunal diverticulum, and finally rearrange the entire small intestine.

The authors discussed the possible causes of small bowel volvulus in this patient. The authors also highlighted the importance of MDCT angiography in the diagnosis of volvulus, and shared our experience in the surgical treatment of this disease.

This is an interesting and well documented report on small bowel volvulus. This report is meaningful as careful evaluation and appropriate surgical treatment can reduce risk of intestinal necrosis and wide intestinal resection.

P- Reviewer: Cotter J, Goetze TO, Hiro J S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Welch GH, Anderson JR. Volvulus of the small intestine in adults. World J Surg. 1986;10:496-500. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Takemura M, Iwamoto K, Goshi S, Osugi H, Kinoshita H. Primary volvulus of the small intestine in an adult, and review of 15 other cases from the Japanese literature. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:52-55. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Frazee RC, Mucha P, Farnell MB, van Heerden JA. Volvulus of the small intestine. Ann Surg. 1988;208:565-568. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Lay PS, Tsang TK, Caprini J, Gardner A, Pollack J, Norman E. Volvulus of the small bowel: an uncommon complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1997;7:59-62. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Huang YM, Wu CC. Whirl sign in small bowel volvulus. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tanaka K, Yamada M, Hatoh T, Adachi T, Matsui K, Tomita H, Osada S, Yoshida K. “Whirl sign”: small bowel volvulus in patients after gastrectomy. Am Surg. 2012;78:E452-E453. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Rowsom JT, Sullivan SN, Girvan DP. Midgut volvulus in the adult. A complication of intestinal malrotation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:212-216. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Duke JH, Yar MS. Primary small bowel volvulus: cause and management. Arch Surg. 1977;112:685-688. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Vaez-Zadeh K, Dutz W, Nowrooz-Zadeh M. Volvulus of the small intestine in adults: a study of predisposing factors. Ann Surg. 1969;169:265-271. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Lempinen M, Salmela K, Kemppainen E. Jejunal diverticulosis: a potentially dangerous entity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:905-909. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fisher JK. Computed tomographic diagnosis of volvulus in intestinal malrotation. Radiology. 1981;140:145-146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 199] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen PC, Redwine MD, Potts JR. Computed tomographic diagnosis of small-bowel volvulus: case report. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1997;48:183-185. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Duda JB, Bhatt S, Dogra VS. Utility of CT whirl sign in guiding management of small-bowel obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:743-747. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Buranasiri SI, Baum S, Nusbaum M, Tumen H. The angiographic diagnosis of midgut malrotation with volvulus in adults. Radiology. 1973;109:555-556. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Feng ST, Chan T, Sun CH, Li ZP, Guo HY, Yang GQ, Peng ZP, Meng QF. Multiphasic MDCT in small bowel volvulus. Eur J Radiol. 2010;76:e13-e18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |