New Software for Gluten-Free Diet Evaluation and Nutritional Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database Preparation

2.2. Software Programming

2.3. Reference Values and Questionnaires

2.4. Software Validity Evaluation

2.5. App Design

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

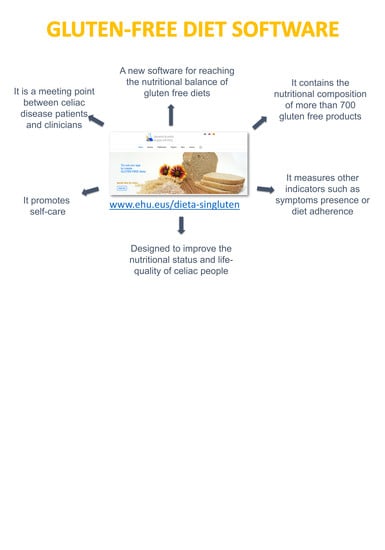

3.1. Software for GFD Evaluation and Design

3.2. App Version of the Software

3.3. Software Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lionetti, E.; Catassi, C. New clues in celiac disease epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and treatment. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 30, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, E.; Larrechi, I.; Churruca, I.; Lasa, A.; Bustamante, M.A.; Navarro, V.; Fernández-Gil, M.P.; Miranda, J. Nutritional and Analytical Approaches of Gluten-Free Diet in Celiac Disease; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Vici, G.; Belli, L.; Biondi, M.; Polzonetti, V. Gluten free diet and nutrient deficiencies: A review. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardella, M.T.; Fredella, C.; Prampolini, L.; Molteni, N.; Giunta, A.M.; Bianchi, P.A. Body composition and dietary intakes in adult celiac disease patients consuming a strict gluten-free diet. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 937–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capristo, E.; Malandrino, N.; Farnetti, S.; Mingrone, G.; Leggio, L.; Addolorato, G.; Gasbarrini, G. Increased serum high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol concentration in celiac disease after gluten-free diet treatment correlates with body fat stores. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2009, 43, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churruca, I.; Miranda, J.; Lasa, A.; Bustamante, M.; Larretxi, I.; Simon, E. Analysis of Body Composition and Food Habits of Spanish Celiac Women. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5515–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, J.; Geisel, T.; Maresch, C.; Krieger, K.; Stein, J. Inadequate nutrient intake in patients with celiac disease: Results from a german dietary survey. Digestion 2013, 87, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theethira, T.G.; Dennis, M. Celiac disease and the gluten-free diet: Consequences and recommendations for improvement. Dig. Dis. 2015, 33, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.; Lasa, A.; Bustamante, M.A.; Churruca, I.; Simon, E. Nutritional Differences Between a Gluten-free Diet and a Diet Containing Equivalent Products with Gluten. Plant Food Hum. Nutr. 2014, 69, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagini, F.; Dilillo, D.; Meneghin, F.; Mameli, C.; Fabiano, V.; Zuccotti, G.V. Gluten-free diet in children: An approach to a nutritionally adequate and balanced diet. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4553–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T. Thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin contents of the gluten-free diet: Is there cause for concern? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1999, 99, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornicelli, M.; Saba, M.; Machello, N.; Silano, M.; Neuhold, S. Nutritional composition of gluten-free food versus regular food sold in the Italian market. Dig. Liver Dis. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulai, T.; Rashid, M. Assessment of Nutritional Adequacy of Packaged Gluten-free Food Products. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2014, 75, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.Á.; Fernández-Gil, M.P.; Churruca, I.; Miranda, J.; Lasa, A.; Navarro, V.; Simon, E. Evolution of Gluten Content in Cereal-Based Gluten-Free Products: An Overview from 1998 to 2016. Nutrients 2017, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, T.; Larretxi, I.; Vitoria, J.C.; Castaño, L.; Simón, E.; Churruca, I.; Navarro, V.; Lasa, A. Celiac Male’s Gluten-Free Diet Profile: Comparison to that of the Control Population and Celiac Women. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larretxi, I.; Simon, E.; Benjumea, L.; Miranda, J.; Bustamante, M.A.; Lasa, A.; Eizaguirre, F.J.; Churruca, I. Gluten-free-rendered products contribute to imbalanced diets in children and adolescents with celiac disease. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larretxi, I.; Txurruka, I.; Navarro, V.; Lasa, A.; Bustamante, M.; Fernández-Gil, M.D.P.; Simón, E.; Miranda, J. Micronutrient Analysis of Gluten-Free Products: Their Low Content Is not Involved in Gluten-Free Diet Imbalance in a Cohort of Celiac Children and Adolescent. Foods 2019, 8, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AESAN. Base de Datos Española de Composición de Alimentos (BEDCA) v 1.0. Available online: http://www.bedca.net/ (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- W3Techs. Available online: https://w3techs.com/ (accessed on 11 September 2019).

- Bel-Serrat, S.; Mouratidou, T.; Pala, V.; Huybrechts, I.; Börnhorst, C.; Fernández-Alvira, J.M.; Hadjigeorgiou, C.; Eiben, G.; Hebestreit, A.; Lissner, L.; et al. Relative validity of the Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire-food frequency section among young European children: The IDEFICS Study. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, V.; Elbusto, A.; Alberdi, M.; De la Presa, A.; Gómez, F.; Portillo, M.; Churruca, I. New pre-coded food record form validation. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet. 2014, 18, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapcich, V.; Salvador, G.; Ribas, L.; Perez, C.; Aranceta, J.; Serra, L. Guía de Alimentación Saludable; Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria (SENC): Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- FESNAD. Dietary reference intakes (DRI) for spanish population. Act. Diet. 2010, 14, 196–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurikka, P.; Salmi, T.; Collin, P.; Huhtala, H.; Mäki, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kurppa, K. Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Celiac Disease Patients on a Long-Term Gluten-Free Diet. Nutrients 2016, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisky, D.E.; Green, L.W.; Levine, D.M. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med. Care 1986, 24, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, R.K.; Winkler, L.M.; Zwinderman, K.H.; Mearin, M.L.; Koopman, H.M. CDDUX: A disease-specific health-related quality-of-life questionnaire for children with celiac disease. J. Pediatric Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2008, 47, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataix, J. Tablas de Composición de Alimentos, 5th ed.; Mataix, J., Ed.; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2009; p. 556. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzini, A.; Lanzarotto, F.; Villanacci, V.; Mora, A.; Bertolazzi, S.; Turini, D.; Carella, G.; Malagoli, A.; Ferrante, G.; Cesana, B.M.; et al. Complete recovery of intestinal mucosa occurs very rarely in adult coeliac patients despite adherence to gluten-free diet. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, D.H.; Donnelly, S.C.; McLaughlin, S.D.; Johnson, M.W.; Ellis, H.J.; Ciclitira, P.J. Celiac disease: Management of persistent symptoms in patients on a gluten-free diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl, B.; Sanders, D.S.; Green, P.H.R. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2018, 391, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, J.A.; Weiten, D.; Graff, L.A.; Walker, J.R.; Duerksen, D.R. Is it gluten-free? Relationship between self-reported gluten-free diet adherence and knowledge of gluten content of foods. Nutrition 2016, 32, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, N.J.; Rubin, G.; Charnock, A. Systematic review: Adherence to a gluten-free diet in adult patients with coeliac disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccotti, G.; Fabiano, V.; Dilillo, D.; Picca, M.; Cravidi, C.; Brambilla, P. Intakes of nutrients in Italian children with celiac disease and the role of commercially available gluten-free products. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, L.; Burden, S.T.; Bannerman, E. A dietary survey to determine if patients with coeliac disease are meeting current healthy eating guidelines and how their diet compares to that of the British general population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.; Dennis, M.; Higgins, L.A.; Lee, A.R.; Sharrett, M.K. Gluten-free diet survey: Are Americans with coeliac disease consuming recommended amounts of fibre, iron, calcium and grain foods? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2005, 18, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, S.J.; Gibson, P.R. Nutritional inadequacies of the gluten-free diet in both recently-diagnosed and long-term patients with coeliac disease. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capristo, E.; Addolorato, G.; Mingrone, G.; De Gaetano, A.; Greco, A.V.; Tataranni, P.A.; Gasbarrini, G. Changes in body composition, substrate oxidation, and resting metabolic rate in adult celiac disease patients after a 1-y gluten-free diet treatment. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, G.R.; Di Sario, A.; Sacco, G.; Zoli, G.; Treggiari, E.A.; Brusco, G.; Gasbarrini, G. Subclinical coeliac disease: An anthropometric assessment. J. Intern. Med. 1994, 236, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capristo, E.; Mingrone, G.; Addolorato, G.; Greco, A.V.; Corazza, G.R.; Gasbarrini, G. Differences in Metabolic Variables between Adult Coeliac Patients at Diagnosis and Patients on a Gluten-Free Diet. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 32, 1222–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, T.A.; Kosma, V.M.; Janatuinen, E.K.; Julkunen, R.J.; Pikkarainen, P.H.; Uusitupa, M.I. Nutritional status of newly diagnosed celiac disease patients before and after the institution of a celiac disease diet--association with the grade of mucosal villous atrophy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 67, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smecuol, E.; Gonzalez, D.; Mautalen, C.; Siccardi, A.; Cataldi, M.; Niveloni, S.; Mazure, R.; Vazquez, H.; Pedreira, S.; Soifer, G.; et al. Longitudinal study on the effect of treatment on body composition and anthropometry of celiac disease patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 92, 639–643. [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury, K.; Mullan, B.; Sharpe, L. A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Online Intervention to Improve Gluten-Free Diet Adherence in Celiac Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zarkadas, M.; Dubois, S.; MacIsaac, K.; Cantin, I.; Rashid, M.; Roberts, K.C.; La Vieille, S.; Godefroy, S.; Pulido, O.M. Living with coeliac disease and a gluten-free diet: A Canadian perspective. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Energy (kcal) | Proteins (g) | Lipids (g) | Carbohydrates (g) | Fiber (g) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By Hand | Software | p | By Hand | Software | p | By Hand | Software | p | By Hand | Software | p | By Hand | Software | p | |

| Hypercaloric | 4808.8 ± 102.6 | 4817.0 ± 167.2 | NS | 179.7 ± 12.1 | 179.0 ± 10.0 | NS | 190.9 ± 11.6 | 196.1 ± 15.3 | NS | 628.0 ± 10.2 | 589.1 ± 7.7 | NS | 66.0 ± 14.0 | 62.7 ± 15.3 | NS |

| Normocaloric | 2549.9 ± 80.0 | 2469.2 ± 37.0 | NS | 99.6 ± 8.4 | 103.3 ± 7.4 | NS | 92.4 ± 3.9 | 89.0 ± 5.4 | NS | 339.9 ± 12.7 | 310.6 ± 7.1 | NS | 32.7 ± 4.6 | 34.2 ± 5.1 | NS |

| Hyperproteic | 2435.3 ± 263.3 | 2531.6 ± 338.2 | NS | 129.8 ± 15.3 | 131.9 ± 12.6 | NS | 92.0 ± 7.8 | 96.9 ± 13.2 | NS | 281.8 ± 40.0 | 279.5 ± 47.1 | NS | 36.6 ± 4.8 | 36.3 ± 8.1 | NS |

| Hyperlipidic | 2743.1 ± 52.9 | 2777.8 ± 83.2 | NS | 102.8 ± 12.8 | 103.2 ± 12.3 | NS | 140.4 ± 13.7 | 145.9 ± 20.3 | NS | 283.5 ± 29.4 | 268.5 ± 36.9 | NS | 36.9 ± 8.8 | 39.4 ± 8.6 | NS |

| GFsoft | GCsoft | p1 | GCAyS | p2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | |||||

| Adults | 1653.4 ± 471.4 | 1627.9 ± 481.0 | 0.08 | 1619.7 ± 480.6 | 0.002 |

| Children | 1817.3 ± 354.0 | 1809.7 ± 360.1 | NS | 1776.9 ± 360.6 | 0.009 |

| Proteins (g) | |||||

| Adults | 84.4 ± 23.5 | 87.5 ± 23.8 | 0.001 | 86.4 ± 23.5 | 0.014 |

| Children | 72.5 ± 14.2 | 77.8 ± 15.0 | <0.001 | 78.2 ± 12.9 | <0.001 |

| Lipids (g) | |||||

| Adults | 69.3 ± 32.0 | 71.7 ± 32.7 | 0.04 | 67.3 ± 31.0 | <0.001 |

| Children | 82.8 ± 28.2 | 81.9 ± 27.6 | NS | 76.0 ± 26.0 | 0.02 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | |||||

| Adults | 157.8 ± 59.8 | 154.3 ± 55.1 | 0.02 | 164.9 ± 59.5 | NS |

| Children | 201.2 ± 56.0 | 197.0 ± 54.1 | 0.01 | 209.3 ± 57.4 | 0.015 |

| Fiber (g) | |||||

| Adults | 15.6 ± 5.8 | 15.8 ± 5.6 | NS | 15.6 ± 6.7 | NS |

| Children | 14.9 ± 4.5 | 14.2 ± 3.8 | NS | 14.6 ± 4.0 | NS |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lasa, A.; Larretxi, I.; Simón, E.; Churruca, I.; Navarro, V.; Martínez, O.; Bustamante, M.Á.; Miranda, J. New Software for Gluten-Free Diet Evaluation and Nutritional Education. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102505

Lasa A, Larretxi I, Simón E, Churruca I, Navarro V, Martínez O, Bustamante MÁ, Miranda J. New Software for Gluten-Free Diet Evaluation and Nutritional Education. Nutrients. 2019; 11(10):2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102505

Chicago/Turabian StyleLasa, Arrate, Idoia Larretxi, Edurne Simón, Itziar Churruca, Virginia Navarro, Olalla Martínez, María Ángeles Bustamante, and Jonatan Miranda. 2019. "New Software for Gluten-Free Diet Evaluation and Nutritional Education" Nutrients 11, no. 10: 2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102505