The Maintenance of Mitochondrial DNA Integrity and Dynamics by Mitochondrial Membranes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Mitochondrial DNA

2.1. The Origins of mtDNA

2.2. mtDNA Replication and Segregation

2.2.1. mtDNA Transcription

2.2.2. mtDNA Replication

2.2.3. Termination of mtDNA Replication

2.2.4. Formation of mtDNA Deletions

2.3. mtDNA Packaging

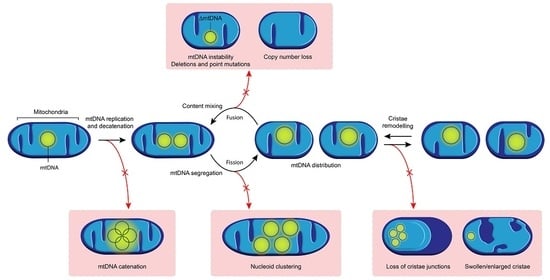

3. Membrane Dynamics and the Organisation of mtDNA

3.1. Mitochondrial Fission and Its Role in mtDNA Distribution

3.1.1. Mitochondrial Fission

3.1.2. Defects in Mitochondrial Fission and Human Disease

3.1.3. Mitochondrial Fission and mtDNA Integrity

3.2. Mitochondrial Fusion and Its Role in mtDNA Maintenance and Distribution

3.2.1. Mitochondrial Fusion

3.2.2. Defects in Mitochondrial Fusion and Human Disease

3.2.3. Mitochondrial Fusion and mtDNA Copy Number

3.2.4. Mitochondrial Fusion and mtDNA Integrity

4. The Relationship between mtDNA and Mitochondrial Cristae Structure

4.1. The Importance of Lipids in the IMM and Their Role in mtDNA Tethering

4.2. Modulators of Cristae Structure

4.3. The Relationship between Cristae Structure and mtDNA

4.4. Cristae Remodelling by Independent Fission and Fusion of Cristae Membranes

4.5. Genetic Defects Associated with Perturbed Mitochondrial Cristae Structure and Diseases

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3-MGA | 3-methylglutoconic aciduria |

| AD | autosomal dominant |

| AR | autosomal recessive |

| ATAD3 | ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 3 |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| CK | creatine kinase |

| CMT | Charcot-Marie-Tooth |

| COX1 | cytochrome c oxidase 1 subunit |

| CPEO | chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| DOA | dominant optic atrophy |

| DD | developmental delay |

| DRP1 | dynamin-related protein 1 |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| ESRF | end-stage renal failure |

| FIS1 | mitochondrial fission 1 protein |

| FSGS | focal segmental glomerulosclerosis |

| GTP | guanine triphosphate |

| HSP | heavy strand promoter |

| IBM | inner boundary membrane |

| IMM | inner mitochondrial membrane |

| IMS | intermembrane space |

| LA | lactic acidosis |

| LS | Leigh syndrome |

| LSP | light strand promoter |

| MCL1 | induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein |

| MEF | mouse embryonic fibroblast |

| MERRF | myoclonic epilepsy and ragged-red fibres |

| MFN | Mitofusin |

| MICOS | mitochondrial contact site and cristae organising system |

| MID49 | mitochondrial dynamics protein of 49kDa |

| MitoPLD | mitochondria-localised phospholipase D |

| MRC | mitochondrial respiratory chain |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| MTERF1 | mitochondrial transcription termination factor 1 |

| mtSSB | mitochondrial single stranded DNA-binding protein |

| NCR | noncoding region |

| OA | optic atrophy |

| OMA1 | overlapping with the M-AAA protease 1 homolog |

| OMM | outer mitochondrial membrane |

| OPA1 | optic atrophy 1 |

| OriH | origin of H-strand replication |

| OriL | origin of L-strand replication |

| OXPHOS | oxidative phosphorylation |

| PA | phosphatidic acid |

| PARL | presenilin-associated rhomboid-like |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| POLγ | DNA polymerase-γ |

| POLRMT | mitochondrial RNA polymerase |

| rRNA | ribosomal RNA |

| RRFs | ragged-red fibres |

| RTA | renal tubular acidosis |

| SCA28 | spinocerebellar ataxia type 28 |

| SNHL | sensorineural hearing loss |

| TEFM | mitochondrial transcription elongation factor |

| TFAM | mitochondrial transcription factor A |

| TFB2M | mitochondrial transcription factor B2 |

| tRNA | transfer RNA |

| VLCFA | very long chain fatty acid |

| WM | white matter |

| YME1L1 | YME1 like 1 ATPase |

Appendix A

| Gene | Protein | Protein Function | Inheritance | Clinical Phenotype | Extra-Neurological | mtDNA Integrity | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulators of Mitochondrial Dynamics | DRP1 | Dynamin-related protein 1 | Mitochondrial fission | AD | Microcephaly, abnormal brain development, OA, LA, elevated VLCFA; DD, refractory epilepsy; isolated DOA (OPA5) | None | EM & confocal microscopy study showing concentric cristae structure in patient-derived fibroblasts [97] | [92,97,257,258] |

| CIV deficiency in muscle [257] | ||||||||

| Elongated mitochondria in optic nerve and RGC layer without axonal degeneration in Dnm1l+/− mice [258] | ||||||||

| No reports of mtDNA deletions or depletion | ||||||||

| DNM2 | Dynamin 2 | Mitochondrial fission | AD | Centronuclear myopathy; dominant intermediate CMT neuropathy type B associated with neutropenia and cataract; CPEO, facial weakness, neck flexor weakness; severe cardiomyopathy and centronuclear myopathy | Cardiac, neutropenia | COX negative fibres and multiple mtDNA deletions in skeletal muscle [103] | [100,101,102,103,259,260] | |

| GDAP1 | Ganglioside Induced Differentiation Associated Protein 1 | Mitochondrial fission | AR | CMT4A (early onset with rapid progression demyelinating neuropathy) | None | No reports of mtDNA deletions or depletion | [93,106,108,109] | |

| AD | CMT2RV (axonal neuropathy with hoarse voice and diaphragmatic weakness) | |||||||

| INF2 | Inverted Formin, FH2 And WH2 Domain Containing | Mitochondrial fission | AD | CMT, dominant, intermediate type, E (CMTDIE) with SNHL and renal phenotype (FSGS, proteinuria and ESRF) | Renal | No reports of mtDNA deletions or depletion | [94,104,105,261] | |

| MFF | Mitochondrial Fission Factor | Mitochondrial fission | AR | DD, pyramidal signs and neuropathy; Leigh-like disease with infantile spasm, OA and neuropathy | None | Normal mitochondrial respiratory chain activities in muscle; significant branching of mitochondria in patient-derived fibroblasts [98] | [95,98,107] | |

| SLC25A46 | Solute Carrier Family 25 Member 46 | Mitochondrial fission | AD | DOA and CMT2; hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy, Type VIB (HMSN6B) | None | Abnormal mitochondrial cristae following knockdown in fibroblasts [99] | [96,99,262,263] | |

| Mitochondrial elongation following knockdown in Zebrafish, mtDNA integrity not assessed [262] | ||||||||

| AR | Progressive myoclonic ataxia, OA and neuropathy; LS; pontocerebellar hypoplasia and apnoea | |||||||

| No reports of mtDNA deletions or depletion | ||||||||

| OPA1 | OPA1 Mitochondrial Dynamin Like GTPase | IM fusion/cristae shaping | AD | DOA (most common genetic cause); DOA plus syndrome (CPEO, ataxia, axonal neuropathy, deafness); syndromic Parkinsonism and dementia | Cardiac | Abnormal cristae in OPA1+/− mouse model [264] | [141,143,174,265,266,267,268,269,270] | |

| AR | Ataxia, early-onset OA, gastrointestinal dysmotility; Behr syndrome (OA and ataxia); Infantile encephalomyopathy, HCM and OA; Leigh-like imaging changes | COX negative fibres and multiple mtDNA deletions in cases of heterozygous mutation [141,174] | ||||||

| Multiple respiratory chain deficiencies and mtDNA depletion in muscle with recessive inheritance [265] | ||||||||

| MFN2 | Mitofusin 2 | OM fusion | AD | CMT2A; DOA plus; DD, progressive weakness, failure to thrive, axonal sensorimotor neuropathy, chorea and elevated CSF lactate | Lipoma | Multiple mtDNA deletions and mtDNA depletion detected in muscles and fibroblasts [154] | [154,157,176,271,272,273,274,275] | |

| AR | Severe, early-onset axonal neuropathy, OA; multiple symmetric lipomatosis, LA and axonal neuropathy | RRFs, COX deficient fibres, altered mitochondrial morphology and multiple mtDNA deletion detected in muscle [176] | ||||||

| COX deficient fibres, ultrastructural changes and mtDNA depletion | ||||||||

| FBLX4 | F-Box And Leucine Rich Repeat Protein 4 | OM fusion | AR | Encephalopathy, microcephaly and persistent LA; encephalomyopathy, abnormal WM changes, LA, dysmorphism, RTA, seizures | Renal (RTA) | Multiple respiratory chain deficiencies and mtDNA depletion in patient-derived fibroblasts [155] | [155,276,277,278,279] | |

| Normal MRC enzymes but mtDNA depletion in muscle [276] | ||||||||

| mtDNA depletion, reduced respiratory function and ultrastructure abnormalities in muscle, reduced respiratory function in fibroblasts [277] | ||||||||

| MSTO1 | Misato Mitochondrial Distribution And Morphology Regulator 1 | Interacts with mitochondrial fusion machinery | AR | Myopathy, elevated CK (1200–4500 IU/L), pigmentary retinopathy, scoliosis and cerebellar ataxia and atrophy | None | Normal MRC enzymes, reduced mtDNA copy number in muscle; mitochondrial fragmentation in patient-derived fibroblasts [280] | [280,281,282] | |

| AD | Myopathy, cerebellar ataxia and non-specific neuropsychiatric symptoms | |||||||

| YME1L1 (YME1) | YME1 like 1 ATPase | OPA1 processing | AR | Intellectual disability, DD, OA, hearing impairment, ataxia, LA, leukoencephalopathic changes on MRI, | None | Altered cristae ultrastructure in muscle, mitochondrial fragmentation in patient-derived fibroblasts [283] | [283] | |

| SPG7 | SPG7 Matrix AAA Peptidase Subunit, Paraplegin | OPA1 processing | AR | Spastic paraplegia 7; spastic ataxia; cerebellar ataxia; CPEO and myopathy; | None | Altered mitochondrial ultrastructure; multiple respiratory chain deficiencies in muscle [147,284] | [147,148,153,284,285] | |

| RRFs, COX-deficient fibres and multiple mtDNA deletions; normal mtDNA copy number in muscle; reduced network size in patient-derived fibroblasts [153] | ||||||||

| AFG3L2 | AFG3 Like Matrix AAA Peptidase Subunit 2 | OPA1 processing | AD | Spinocerebellar ataxia 28 (SCA28); CPEO | None | RRFs, COX deficient fibres and multiple mtDNA deletions in muscle [152] | [152,286,287,288] | |

| Regulators of Cristae Structure | MICOS13 (MIC13; QIL1) | Mitochondrial Contact Site And Cristae Organizing System Subunit 13 | Stabilises MIC60 and MIC10 in the MICOS Complex | AR | Failure to thrive, acquired microcephaly, truncal hypotonia, limb spasticity cerebellar atrophy, LA, 3-MGA, elevated liver transaminases and myoclonic seizures | Liver | Normal histology and MRC activities in muscle; low MRC enzymatic activities and abnormal cristae in liver [243] | [243,244] |

| Multiple respiratory chain deficiencies in muscle and liver [244] | ||||||||

| APOO (MIC26) | Apolipoprotein O | Regulatory role in MICOS complex | X-linked | DD, myopathy, LA, cognitive impairment, autistic features, abnormal acylcarnitidine profile | None | Abnormal ultrastructure in fibroblasts and a Drosophila Melanogaster model [245] | [245] | |

| CHCHD10 | Coiled-Coil-Helix-Coiled-Coil-Helix Domain Containing 10 | Stabilises MICOS complex | AD | Frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; late onset spinal motor neuronopathy and elevated CK; myopathy, elevated CK and lactate; CMT2 | None | RRFs, COX deficient fibres, multiple respiratory chain deficiencies, abnormal assembly of CV, multiple mtDNA deletions in muscle, reduced fusion and loss of cristae structure in patient-derived fibroblast [251] | [239,251,252,289,290,291,292] | |

| Mildly increased COX deficient fibres and occasional RRFs [290] and multiple mtDNA deletions [290] | ||||||||

| Multiple respiratory chain deficiencies (worst with CIV), RRFs, lipid accumulation and abnormal circular cristae ultrastructure [291] | ||||||||

| Loss of mitochondrial cristae junctions with impaired mitochondrial genome maintenance and inhibition of apoptosis in patient-derived fibroblasts [239] | ||||||||

| PINK1 | PTEN Induced Kinase 1 | Mitophagy/Interacts with MIC60 to regulate CJs | AR | Parkinson disease 6 (PARK6) | None | Complex I deficiency in Drosophila Melanogaster model [293] | [246,293,294,295,296,297] | |

| ATP5F1E F1Fo-ATP synthase (sub unit E) | ATP Synthase F1 Subunit Epsilon | Cristae shaping/ATP Production | AR | LA, 3-MGA, mild mental retardation and development of peripheral neuropathy | None | Complex V deficiency in patient-derived fibroblasts [256] | [256] | |

| ATP5F1A F1Fo-ATP synthase (sub unit a) | ATP Synthase F1 Subunit Alpha | Cristae shaping/ATP production | AR | Intrauterine growth retardation, microcephaly, hypotonia, pulmonary hypertension, failure to thrive, encephalopathy, and heart failure; neonatal-onset encephalopathy with intractable seizures, extensive signal changes involving WM, basal ganglia and thalamus | Cardiac | Multiple respiratory chain deficiency and mtDNA depletion in muscle [298] | [298,299] | |

| Complex V deficiency in muscle [299] | ||||||||

| IMM Structure | ATAD3A | ATPase Family AAA Domain Containing 3A | mtDNA and cristae organisation | De novo & AR | Global DD, hypotonia, OA, axonal neuropathy, mildly elevated lactate, seizures, 3-MGA and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; fatal congenital pontocerebellar hypoplasia with a simplified gyral pattern; cerebellar atrophy with dystonia and ataxia | Cardiac | Abnormal cristae in Drosophila Melanogaster and patient-derived fibroblasts [253] | [171,253] |

| mtDNA abnormalities in patient-derived fibroblasts [171] | ||||||||

| TAZ | Tafazzin | Organisation of cardiolipin in the IM | X-linked | Severe infantile cardiomyopathy (left ventricular noncompaction, Barth syndrome with dilated cardiomyopathy), sudden cardiac death, myopathy, neutropenia, growth failure, 3-MGA, facial dysmorphism | Cardiac, neutropenia | Altered mitochondrial ultrastructure, stacked and circular cristae, in patient-derived lymphoblasts [300] | [254,255,300,301,302,303,304] |

References

- Gray, M.W. Mitochondrial Evolution. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a011403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gualberto, J.; Mileshina, D.; Wallet, C.; Niazi, A.K.; Weber-Lotfi, F.; Dietrich, A. The plant mitochondrial genome: Dynamics and maintenance. Biochimie 2014, 100, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foury, F.; Roganti, T.; Lecrenier, N.; Purnelle, B. The complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1998, 440, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrews, R.M.; Kubacka, I.; Chinnery, P.F.; Chrzanowska-Lightowlers, Z.M.; Turnbull, D.M.; Howell, N. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaban, Y.; Boekema, E.J.; Dudkina, N.V. Structures of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation supercomplexes and mechanisms for their stabilisation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1837, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calvo, S.E.; Clauser, K.R.; Mootha, V.K. MitoCarta2.0: An updated inventory of mammalian mitochondrial proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D1251–D1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnery, P.F.; Hudson, G. Mitochondrial genetics. Br. Med. Bull. 2013, 106, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falkenberg, M.; Larsson, N.-G.; Gustafsson, C.M. DNA Replication and Transcription in Mammalian Mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 679–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C.M.; Falkenberg, M.; Larsson, N.-G. Maintenance and Expression of Mammalian Mitochondrial DNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016, 85, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, M. Mitochondrial DNA replication in mammalian cells: Overview of the pathway. Essays Biochem. 2018, 62, 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Berk, A.J.; Clayton, D.A. Mechanism of mitochondrial DNA replication in mouse L-cells: Asynchronous replication of strands, segregation of circular daughter molecules, aspects of topology and turnover of an initiation sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 1974, 86, 801–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, M.; Gaspari, M.; Rantanen, A.; Trifunovic, A.; Larsson, N.-G.; Gustafsson, C.M. Mitochondrial transcription factors B1 and B2 activate transcription of human mtDNA. Nat. Genet. 2002, 31, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillen, H.S.; Morozov, Y.I.; Sarfallah, A.; Temiakov, D.; Cramer, P. Structural Basis of Mitochondrial Transcription Initiation. Cell 2017, 171, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minczuk, M.; He, J.; Duch, A.M.; Ettema, T.J.; Chlebowski, A.; Dzionek, K.; Nijtmans, L.G.; Huynen, M.A.; Holt, I.J. TEFM (c17orf42) is necessary for transcription of human mtDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 4284–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Posse, V.; Shahzad, S.; Falkenberg, M.; Hallberg, B.M.; Gustafsson, C.M. TEFM is a potent stimulator of mitochondrial transcription elongation in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 2615–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posse, V.; Al-Behadili, A.; Uhler, J.P.; Clausen, A.R.; Reyes, A.; Zeviani, M.; Falkenberg, M.; Gustafsson, C.M. RNase H1 directs origin-specific initiation of DNA replication in human mitochondria. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wanrooij, P.H.; Uhler, J.P.; Simonsson, T.; Falkenberg, M.; Gustafsson, C.M. G-quadruplex structures in RNA stimulate mitochondrial transcription termination and primer formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16072–16077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wanrooij, P.H.; Uhler, J.P.; Shi, Y.; Westerlund, F.; Falkenberg, M.; Gustafsson, C.M. A hybrid G-quadruplex structure formed between RNA and DNA explains the extraordinary stability of the mitochondrial R-loop. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 10334–10344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, H.; Wong, T.W. Purification and identification of subunit structure of the human mitochondrial DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 5835–5841. [Google Scholar]

- Yakubovskaya, E.; Chen, Z.; Carrodeguas, J.A.; Kisker, C.; Bogenhagen, D.F. Functional human mitochondrial dna polymerase forms a heterotrimer. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 281, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Kennedy, W.D.; Yin, Y.W. Structural insight into processive human mitochondrial DNA synthesis and disease-related polymerase mutations. Cell 2009, 139, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carrodeguas, J.A.; Pinz, K.G.; Bogenhagen, D.F. DNA binding properties of human pol, γB. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 50008–50014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Korhonen, J.A.; Pham, X.H.; Pellegrini, M.; Falkenberg, M. Reconstitution of a minimal mtDNA replisome in vitro. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 2423–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korhonen, J.A.; Gaspari, M.; Falkenberg, M. TWINKLE Has 5′ -> 3′ DNA Helicase Activity and Is Specifically Stimulated by Mitochondrial Single-stranded DNA-binding Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 48627–48632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martens, P.A.; Clayton, D.A. Mechanism of mitochondrial DNA replication in mouse L-cells: Localization and sequence of the light-strand origin of replication. J. Mol. Biol. 1979, 135, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté, J.M.; Wanrooij, S.; Jemt, E.; Granycome, C.E.; Cluett, T.J.; Shi, Y.; Atanassova, N.; Holt, I.J.; Gustafsson, C.M.; Falkenberg, M. Mitochondrial RNA Polymerase Is Needed for Activation of the Origin of Light-Strand DNA Replication. Mol. Cell 2010, 37, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanrooij, S.; Fuste, J.M.; Farge, G.; Shi, Y.; Gustafsson, C.M.; Falkenberg, M. Human mitochondrial RNA polymerase primes lagging-strand DNA synthesis in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11122–11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reyes, A.; Kazak, L.; Wood, S.R.; Yasukawa, T.; Jacobs, H.T.; Holt, I.J. Mitochondrial DNA replication proceeds via a ‘bootlace’ mechanism involving the incorporation of processed transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 5837–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yasukawa, T.; Kang, N. An overview of mammalian mitochondrial DNA replication mechanisms. J. Biochem. 2018, 164, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, I.J.; Jacobs, H.T. Unique features of DNA replication in mitochondria: A functional and evolutionary perspective. BioEssays 2014, 36, 1024–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, I.; Lorimer, H.E.; Jacobs, H.T. Coupled Leading- and Lagging-Strand Synthesis of Mammalian Mitochondrial DNA. Cell 2000, 100, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holmes, J.B.; Akman, G.; Wood, S.R.; Sakhuja, K.; Cerritelli, S.M.; Moss, C.; Bowmaker, M.R.; Jacobs, H.T.; Crouch, R.J.; Holt, I.J.; et al. Primer retention owing to the absence of RNase H1 is catastrophic for mitochondrial DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9334–9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Behadili, A.; Uhler, J.P.; Berglund, A.K.; Peter, B.; Doimo, M.; Reyes, A.; Wanrooij, S.; Zeviani, M.; Falkenberg, M. A two-nuclease pathway involving RNase H1 is required for primer removal at human mitochondrial, O.r.i.L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 9471–9483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cerritelli, S.M.; Frolova, E.G.; Feng, C.; Grinberg, A.; Love, P.E.; Crouch, R.J. Failure to Produce Mitochondrial DNA Results in Embryonic Lethality in Rnaseh1 Null Mice. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmipathy, U.; Campbell, C. The Human DNA Ligase III Gene Encodes Nuclear and Mitochondrial Proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 3869–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uhler, J.P.; Thörn, C.; Nicholls, T.J.; Matic, S.; Milenkovic, D.; Gustafsson, C.M.; Falkenberg, M. MGME1 processes flaps into ligatable nicks in concert with DNA polymerase gamma during mtDNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 5861–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicholls, T.J.; Zsurka, G.; Peeva, V.; Schöler, S.; Szczesny, R.J.; Cysewski, D.; Reyes, A.; Kornblum, C.; Sciacco, M.; Moggio, M.; et al. Linear mtDNA fragments and unusual mtDNA rearrangements associated with pathological deficiency of MGME1 exonuclease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 6147–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicholls, T.J.; Nadalutti, C.A.; Motori, E.; Sommerville, E.W.; Gorman, G.S.; Basu, S.; Hoberg, E.; Turnbull, D.M.; Chinnery, P.F.; Larsson, N.G.; et al. Topoisomerase 3alpha Is Required for Decatenation Segregation of Human mtDNA. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 9–23.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorman, G.S.; Chinnery, P.F.; DiMauro, S.; Hirano, M.; Koga, Y.; McFarland, R.; Suomalainen, A.; Thorburn, D.R.; Zeviani, M.; Turnbull, D.M. Mitochondrial diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, E.A.; Rizzuto, R.; Moraes, C.T.; Nakase, H.; Zeviani, M.; DiMauro, S. A direct repeat is a hotspot for large-scale deletion of human mitochondrial DNA. Science 1989, 244, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscomi, C.; Zeviani, M. MtDNA-maintenance defects: Syndromes and genes. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017, 40, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bender, A.; Krishnan, K.J.; Morris, C.M.; Taylor, G.A.; Reeve, A.K.; Perry, R.H.; Jaros, E.; Hersheson, J.S.; Betts, J.; Klopstock, T.; et al. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraytsberg, Y.; Kudryavtseva, E.; McKee, A.C.; Geula, C.; Kowall, N.W.; Khrapko, K. Mitochondrial DNA deletions are abundant and cause functional impairment in aged human substantia nigra neurons. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 518–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawless, C.; Greaves, L.C.; Reeve, A.K.; Turnbull, D.M.; Vincent, A.E. The rise and rise of mitochondrial DNA mutations. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissanka, N.; Minczuk, M.; Moraes, C.T. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial DNA Deletion Formation. Trends Genet. 2019, 35, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoffner, J.M.; Lott, M.T.; Voljavec, A.S.; Soueidan, S.A.; Costigan, D.A.; Wallace, D.C. Spontaneous Kearns-Sayre/chronic external ophthalmoplegia plus syndrome associated with a mitochondrial DNA deletion: A slip-replication model and metabolic therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7952–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Persson, Ö.; Muthukumar, Y.; Basu, S.; Jenninger, L.; Uhler, J.P.; Berglund, A.-K.; McFarland, R.; Taylor, R.W.; Gustafsson, C.M.; Larsson, E. Copy-choice recombination during mitochondrial L-strand synthesis causes DNA deletions. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nissanka, N.; Bacman, S.R.; Plastini, M.; Moraes, C.T. The mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma degrades linear DNA fragments precluding the formation of deletions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Moraes, C.T. Double-strand breaks of mouse muscle mtDNA promote large deletions similar to multiple mtDNA deletions in humans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bacman, S.R.; Williams, S.L.; Moraes, C.T. Intra-and inter-molecular recombination of mitochondrial DNA after in vivo induction of multiple double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 4218–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krishnan, K.J.; Reeve, A.K.; Samuels, D.C.; Chinnery, P.F.; Blackwood, J.K.; Taylor, R.W.; Wanrooij, S.; Spelbrink, J.N.; Chrzanowska-Lightowlers, Z.M.; Turnbull, D.M. What causes mitochondrial DNA deletions in human cells? Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farge, G.; Mehmedovic, M.; Baclayon, M.; Wildenberg, S.M.V.D.; Roos, W.H.; Gustafsson, C.M.; Wuite, G.J.; Falkenberg, M. In Vitro-Reconstituted Nucleoids Can Block Mitochondrial DNA Replication and Transcription. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, T.A.; Tkachuk, A.N.; Shtengel, G.; Kopek, B.G.; Bogenhagen, D.F.; Hess, H.F.; Clayton, D.A. Superresolution fluorescence imaging of mitochondrial nucleoids reveals their spatial range, limits, and membrane interaction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31, 4994–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kukat, C.; Wurm, C.A.; Spahr, H.; Falkenberg, M.; Larsson, N.G.; Jakobs, S. Super-resolution microscopy reveals that mammalian mitochondrial nucleoids have a uniform size and frequently contain a single copy of mtDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13534–13539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaufman, B.A.; Durisic, N.; Mativetsky, J.M.; Costantino, S.; Hancock, M.A.; Grutter, P.; Shoubridge, E.A. The Mitochondrial Transcription Factor TFAM Coordinates the Assembly of Multiple DNA Molecules into Nucleoid-like Structures. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 3225–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, M.I.; Falkenberg, M.; Rantanen, A.; Park, C.B.; Gaspari, M.; Hultenby, K.; Rustin, P.; Gustafsson, C.M.; Larsson, N.-G. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mtDNA copy number in mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenhagen, D.F. Mitochondrial DNA nucleoid structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1819, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, C.; Umeda, S.; Ohsato, T.; Ohno, T.; Abe, Y.; Fukuoh, A.; Shinagawa, H.; Hamasaki, N.; Kang, D. Regulation of mitochondrial D-loops by transcription factor A and single-stranded DNA-binding protein. EMBO Rep. 2002, 3, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Bogenhagen, D.F. Human Mitochondrial DNA Nucleoids Are Linked to Protein Folding Machinery and Metabolic Enzymes at the Mitochondrial Inner Membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 25791–25802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, J.; Cooper, H.M.; Reyes, A.; Di Re, M.; Sembongi, H.; Litwin, T.R.; Gao, J.; Neuman, K.C.; Fearnley, I.M.; Spinazzola, A. Mitochondrial nucleoid interacting proteins support mitochondrial protein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 6109–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, S.; Udeshi, N.D.; Deerinck, T.J.; Svinkina, T.; Ellisman, M.H.; Carr, S.A.; Ting, A.Y. Proximity Biotinylation as a Method for Mapping Proteins Associated with mtDNA in Living Cells. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bogenhagen, D.F.; Rousseau, D.; Burke, S. The Layered Structure of Human Mitochondrial DNA Nucleoids. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 283, 3665–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Couvillion, M.T.; Soto, I.C.; Shipkovenska, G.; Churchman, L.S. Synchronized mitochondrial and cytosolic translation programs. Nature 2016, 533, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richter-Dennerlein, R.; Oeljeklaus, S.; Lorenzi, I.; Ronsör, C.; Bareth, B.; Schendzielorz, A.B.; Wang, C.; Warscheid, B.; Rehling, P.; Dennerlein, S. Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis Adapts to Influx of Nuclear-Encoded Protein. Cell 2016, 167, 471–483.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilkerson, R.W.; Schon, E.A.; Hernandez, E.; Davidson, M.M. Mitochondrial nucleoids maintain genetic autonomy but allow for functional complementation. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 181, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, T.; Ban-Ishihara, R.; Maeda, M.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ichimura, A.; Kyogoku, S.; Aoki, H.; Katada, S.; Nakada, K.; Nomura, M. Dynamics of Mitochondrial DNA Nucleoids Regulated by Mitochondrial Fission Is Essential for Maintenance of Homogeneously Active Mitochondria during Neonatal Heart Development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 35, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nass, M.M. Mitochondrial DNA. I. Intramitochondrial distribution and structural relations of single- \and double-length circular DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1969, 42, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopek, B.G.; Shtengel, G.; Xu, C.S.; Clayton, D.A.; Hess, H.F. Correlative 3D superresolution fluorescence and electron microscopy reveal the relationship of mitochondrial nucleoids to membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6136–6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iborra, F.J.; Kimura, H.; Cook, P.R. The functional organisation of mitochondrial genomes in human cells. BMC Biol. 2004, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albring, M.; Griffith, J.; Attardi, G. Association of a protein structure of probable membrane derivation with HeLa cell mitochondrial DNA near its origin of replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 1348–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, T.J.; Berridge, M.J.; Lipp, P.; Bootman, M.D. Mitochondria are morphologically and functionally heterogeneous within cells. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 1616–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, L.C.G.; Scorrano, L. Mitochondrial morphology in mitophagy and macroautophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Youle, R.J. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009, 43, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chapman, J.; Fielder, E.; Passos, J.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and cell senescence: Deciphering a complex relationship. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 1566–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewis, S.C.; Uchiyama, L.; Nunnari, J. ER-mitochondria contacts couple mtDNA synthesis with mitochondrial division in human cells. Science 2016, 353, aaf5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murley, A.; Lackner, L.L.; Osman, C.; West, M.; Voeltz, G.K.; Walter, P.; Nunnari, J.; Youle, R.J. ER-associated mitochondrial division links the distribution of mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in yeast. ELife 2013, 2, e00422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban-Ishihara, R.; Ishihara, T.; Sasaki, N.; Mihara, K.; Ishihara, N. Dynamics of nucleoid structure regulated by mitochondrial fission contributes to cristae reformation and release of cytochrome c. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 11863–11868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, J.R.; Lackner, L.L.; West, M.; DiBenedetto, J.R.; Nunnari, J.; Voeltz, G.K. ER Tubules Mark Sites of Mitochondrial Division. Science 2011, 334, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korobova, F.; Ramabhadran, V.; Higgs, H.N. An Actin-Dependent Step in Mitochondrial Fission Mediated by the ER-Associated Formin INF2. Science 2013, 339, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manor, U.; Bartholomew, S.; Golani, G.; Christenson, E.; Kozlov, M.; Higgs, H.N.; Spudich, J.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. A mitochondria-anchored isoform of the actin-nucleating spire protein regulates mitochondrial division. ELife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, E.; Griparic, L.; Shurland, D.-L.; Van Der Bliek, A.M. Dynamin-related Protein Drp1 Is Required for Mitochondrial Division in Mammalian Cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 2245–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Otera, H.; Wang, C.; Cleland, M.M.; Setoguchi, K.; Yokota, S.; Youle, R.J.; Mihara, K. Mff is an essential factor for mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 during mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- James, D.I.; Parone, P.A.; Mattenberger, Y.; Martinou, J.-C. hFis1, a Novel Component of the Mammalian Mitochondrial Fission Machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36373–36379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Palmer, C.S.; Osellame, L.D.; Laine, D.; Koutsopoulos, O.S.; Frazier, A.E.; Ryan, M.T. MiD49 and MiD51, new components of the mitochondrial fission machinery. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losón, O.C.; Song, Z.; Chen, H.; Chan, D.C. Fis1, Mff, MiD49, and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in mitochondrial fission. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, R.; Wang, R.Y.-R.; Yusuf, A.; Thomas, P.V.; Agard, D.A.; Shaw, J.M.; Frost, A. Structural basis of mitochondrial receptor binding and constriction by DRP1. Nature 2018, 558, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamerkar, S.; Kraus, F.; Sharpe, A.; Pucadyil, T.J.; Ryan, M.T. Dynamin-related protein 1 has membrane constricting and severing abilities sufficient for mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, T.B.; Sánchez-Guerrero, Á.; Milosevic, I.; Raimundo, N. Mitochondrial fission requires DRP1 but not dynamins. Nature 2019, 570, E34–E42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.C.; Ysselstein, D.; Krainc, D. Mitochondria–lysosome contacts regulate mitochondrial fission via RAB7 GTP hydrolysis. Nature 2018, 554, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, S.; Tábara, L.-C.; Tilokani, L.; Paupe, V.; Anand, H.; Pogson, J.H.; Zunino, R.; McBride, H.M.; Prudent, J. Golgi-derived PI(4)P-containing vesicles drive late steps of mitochondrial division. Science 2020, 367, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, N.; Griparic, L.; Jokitalo, E.; Wartiovaara, J.; Van Der Bliek, A.M.; Spelbrink, J.N. Composition and Dynamics of Human Mitochondrial Nucleoids. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 1583–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waterham, H.R.; Koster, J.; Van Roermund, C.W.; Mooyer, P.A.; Wanders, R.J.; Leonard, J.V. A Lethal Defect of Mitochondrial and Peroxisomal Fission. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, R.V.; Ben Othmane, K.; Rochelle, J.M.; Stajich, J.E.; Hulette, C.; Dew-Knight, S.; Hentati, F.; Ben Hamida, M.; Bel, S.; Stenger, J.E. Ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated protein-1 is mutant in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4A/8q21. Nat. Genet. 2001, 30, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.J.; Schlöndorff, J.S.; Becker, D.J.; Tsukaguchi, H.; Tonna, S.J.; Uscinski, A.L.; Higgs, H.N.; Henderson, J.M.; Pollak, M.R. Mutations in the formin gene INF2 cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamseldin, H.E.; Alshammari, M.; Al-Sheddi, T.; Salih, M.A.M.; Alkhalidi, H.; Kentab, A.; Repetto, G.M.; Hashem, M.O.; Alkuraya, F.S. Genomic analysis of mitochondrial diseases in a consanguineous population reveals novel candidate disease genes. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, A.J.; Hufnagel, R.B.; Rebelo, A.; Zanna, C.; Patel, N.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Campeanu, I.J.; Griffin, L.B.; Groenewald, S.; Strickland, A.V.; et al. Mutations in SLC25A46, encoding a UGO1-like protein, cause an optic atrophy spectrum disorder. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanstone, J.R.; Smith, A.M.; McBride, S.; Naas, T.; Holčík, M.; Antoun, G.; Harper, M.-E.; Michaud, J.; Sell, E.; Chakraborty, P.; et al. DNM1L-related mitochondrial fission defect presenting as refractory epilepsy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 24, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, J.; Feichtinger, R.G.; Freisinger, P.; Pies, M.; Schrödl, F.; Iuso, A.; Sperl, W.; Mayr, J.A.; Prokisch, H.; Haack, T.B. Disturbed mitochondrial and peroxisomal dynamics due to loss of MFF causes Leigh-like encephalopathy, optic atrophy and peripheral neuropathy. J. Med. Genet. 2016, 53, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janer, A.; Prudent, J.; Paupe, V.; Fahiminiya, S.; Majewski, J.; Sgarioto, N.; Rosiers, C.D.; Forest, A.; Lin, Z.; Gingras, A.-C.; et al. SLC 25A46 is required for mitochondrial lipid homeostasis and cristae maintenance and is responsible for Leigh syndrome. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 1019–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitoun, M.; Maugenre, S.; Jeannet, P.Y.; Lacène, E.; Ferrer, X.; Laforêt, P.; Martin, J.J.; Laporte, J.; Lochmüller, H.; Beggs, A.H.; et al. Mutations in dynamin 2 cause dominant centronuclear myopathy. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 1207–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, K.G.; Züchner, S.; Kennerson, M.; Berciano, J.; Garcia, A.; Verhoeven, K.; Storey, E.; Merory, J.R.; Bienfait, H.M.E.; Lammens, M.; et al. Phenotypic spectrum of dynamin 2 mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Brain 2009, 132 Pt 7, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, J.; Biancalana, V.; Dechene, E.T.; Bitoun, M.; Pierson, C.R.; Schaefer, E.; Karasoy, H.; Dempsey, M.A.; Klein, F.; Dondaine, N.; et al. Mutation spectrum in the large GTPase dynamin 2, and genotype-phenotype correlation in autosomal dominant centronuclear myopathy. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gal, A.; Inczedy-Farkas, G.; Pál, E.; Remenyi, V.; Bereznai, B.; Gellér, L.; Szelid, Z.; Merkely, B.; Molnar, M.J. The coexistence of dynamin 2 mutation and multiple mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) deletions in the background of severe cardiomyopathy and centronuclear myopathy. Clin. Neuropathol. 2015, 34, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boyer, O.; Nevo, F.; Plaisier, E.; Funalot, B.; Gribouval, O.; Benoit, G.; Huynh Cong, E.; Arrondel, C.; Tête, M.J.; Montjean, R.; et al. INF2Mutations in Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease with Glomerulopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2377–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caridi, G.; Lugani, F.; Dagnino, M.; Gigante, M.; Iolascon, A.; Falco, M.; Graziano, C.; Benetti, E.; Dugo, M.; Del Prete, D.; et al. Novel INF2 mutations in an Italian cohort of patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, renal failure and Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2014, 29 (Suppl. S4), iv80–iv86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crimella, C.; Tonelli, A.; Airoldi, G.; Baschirotto, C.; D’Angelo, M.G.; Bonato, S.; Losito, L.; Trabacca, A.; Bresolin, N.; Bassi, M.T.; et al. The GST domain of GDAP1 is a frequent target of mutations in the dominant form of axonal Charcot Marie Tooth type, 2.K. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 47, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nasca, A.; Nardecchia, F.; Commone, A.; Semeraro, M.; Legati, A.; Garavaglia, B.; Ghezzi, D.; Leuzzi, V. Clinical and Biochemical Features in a Patient With Mitochondrial Fission Factor Gene Alteration. Front. Genet. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedrola, L.; Espert, A.; Wu, X.; Claramunt, R.; Shy, M.E.; Palau, F. GDAP1, the protein causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4A, is expressed in neurons and is associated with mitochondria. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzini, I.; Geroldi, A.; Capponi, S.; Gulli, R.; Schenone, A.; Grandis, M.; Doria-Lamba, L.; La Piana, C.; Cremonte, M.; Pisciotta, C.; et al. GDAP1 mutations in Italian axonal Charcot–Marie–Tooth patients: Phenotypic features and clinical course. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2016, 26, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parone, P.A.; Da Cruz, S.; Tondera, D.; Mattenberger, Y.; James, D.I.; Maechler, P.; Barja, F.; Martinou, J.C. Preventing Mitochondrial Fission Impairs Mitochondrial Function and Leads to Loss of Mitochondrial DNA. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishihara, N.; Nomura, M.; Jofuku, A.; Kato, H.; Suzuki, S.O.; Masuda, K.; Otera, H.; Nakanishi, Y.; Nonaka, I.; Goto, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial fission factor Drp1 is essential for embryonic development and synapse formation in mice. Nature 2009, 11, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wakabayashi, N.; Tamura, Y.; Fukaya, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Iijima, M.; Sesaki, H. The dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 is required for embryonic and brain development in mice. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Ren, S.; Clish, C.; Jain, M.; Mootha, V.; McCaffery, J.M.; Chan, D.C. Titration of mitochondrial fusion rescues Mff-deficient cardiomyopathy. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 211, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kameoka, S.; Adachi, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Iijima, M.; Sesaki, H. Phosphatidic Acid and Cardiolipin Coordinate Mitochondrial Dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 28, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, P.J.; Stepanyants, N.; Mehrotra, N.; Mears, J.A.; Qi, X.; Sesaki, H.; Ramachandran, R. A dimeric equilibrium intermediate nucleates Drp1 reassembly on mitochondrial membranes for fission. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 1905–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francy, C.A.; Alvarez, F.J.D.; Zhou, L.; Ramachandran, R.; Mears, J.A. The Mechanoenzymatic Core of Dynamin-related Protein 1 Comprises the Minimal Machinery Required for Membrane Constriction. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 11692–11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Francy, C.A.; Clinton, R.W.; Fröhlich, C.; Murphy, C.; Mears, J.A. Cryo-EM Studies of Drp1 Reveal Cardiolipin Interactions that Activate the Helical Oligomer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyants, N.; Macdonald, P.J.; Francy, C.A.; Mears, J.A.; Qi, X.; Ramachandran, R. Cardiolipin’s propensity for phase transition and its reorganisation by dynamin-related protein 1 form a basis for mitochondrial membrane fission. Mol. Biol. Cell 2015, 26, 3104–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dachi, Y.; Itoh, K.; Yamada, T.; Cerveny, K.L.; Suzuki, T.L.; Macdonald, P.; Frohman, M.A.; Ramachandran, R.; Iijima, M.; Sesaki, H. Coincident Phosphatidic Acid Interaction Restrains Drp1 in Mitochondrial Division. Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Luévano-Martínez, L.A.; Forni, M.F.; Dos Santos, V.T.; Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Kowaltowski, A.J. Cardiolipin is a key determinant for mtDNA stability and segregation during mitochondrial stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1847, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, Q.; Gohil, V.M.; Ma, L.; Greenberg, M.L. Absence of Cardiolipin Results in Temperature Sensitivity, Respiratory Defects, and Mitochondrial DNA Instability Independent of pet56. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 32294–32300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Finley, R.L.; Greenberg, M.L., Jr. Loss of mitochondrial DNA in the yeast cardiolipin synthase crd1 mutant leads to up-regulation of the protein kinase Swe1p that regulates the G2/M transition. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 10397–10407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Acehan, D.; Malhotra, A.; Xu, Y.; Ren, M.; Stokes, D.L.; Schlame, M. Cardiolipin Affects the Supramolecular Organisation of ATP Synthase in Mitochondria. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ono, T.; Isobe, K.; Nakada, K.; Hayashi, J.-I. Human cells are protected from mitochondrial dysfunction by complementation of DNA products in fused mitochondria. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.L.; Meng, S.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J.X.; Gu, D.D.; Yu, B.; Li, Y.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Liao, S.; Chan, D.C.; et al. MFN1 structures reveal nucleotide-triggered dimerization critical for mitochondrial fusion. Nature 2017, 542, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Qi, Y.; Huang, X.; Yu, C.; Lan, L.; Guo, X.; Rao, Z.; Hu, J.; Lou, Z. Structural basis for GTP hydrolysis and conformational change of MFN1 in mediating membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018, 25, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Yan, L.; Yu, C.; Guo, X.; Zhou, X.; Hu, X.; Huang, X.; Rao, Z.; Lou, Z.; Hu, J. Structures of human mitofusin 1 provide insight into mitochondrial tethering. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishihara, N.; Eura, Y.; Mihara, K. Mitofusin 1 and 2 play distinct roles in mitochondrial fusion reactions via GTPase activity. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 6535–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Brito, O.M.; Scorrano, L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature 2008, 456, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filadi, R.; Greotti, E.; Turacchio, G.; Luini, A.; Pozzan, T.; Pizzo, P. Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E2174–E2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wai, T.; Garcia-Prieto, J.; Baker, M.J.; Merkwirth, C.; Benit, P.; Rustin, P.; Ruperez, F.J.; Barbas, C.; Ibanez, B.; Langer, T. Imbalanced OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fragmentation cause heart failure in mice. Science 2015, 350, aad0116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griparic, L.; Kanazawa, T.; Van Der Bliek, A.M. Regulation of the mitochondrial dynamin-like protein Opa1 by proteolytic cleavage. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 178, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ehses, S.; Raschke, I.; Mancuso, G.; Bernacchia, A.; Geimer, S.; Tondera, D.; Martinou, J.C.; Westermann, B.; Rugarli, E.I.; Langer, T. Regulation of OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fusion by m-AAA protease isoenzymes and OMA1. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, E.S.; Motori, E.; Bruser, C.; Kuhl, I.; Yeroslaviz, A.; Ruzzenente, B.; Kauppila, J.H.K.; Busch, J.D.; Hultenby, K.; Habermann, B.H.; et al. Mitochondrial fusion is required for regulation of mitochondrial DNA replication. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elachouri, G.; Vidoni, S.; Zanna, C.; Pattyn, A.; Boukhaddaoui, H.; Gaget, K.; Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Gasparre, G.; Sarzi, E.; Delettre, C.; et al. OPA1 links human mitochondrial genome maintenance to mtDNA replication and distribution. Genome Res. 2010, 21, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Vermulst, M.; Wang, Y.E.; Chomyn, A.; Prolla, T.A.; McCaffery, J.M.; Chan, D.C. Mitochondrial Fusion Is Required for mtDNA Stability in Skeletal Muscle and Tolerance of mtDNA Mutations. Cell 2010, 141, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sugiura, A.; Nagashima, S.; Tokuyama, T.; Amo, T.; Matsuki, Y.; Ishido, S.; Kudo, Y.; McBride, H.M.; Fukuda, T.; Matsushita, N.; et al. MITOL Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Contacts via Mitofusin2. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Csordás, G.; Jowdy, C.; Schneider, T.G.; Csordás, N.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Kohlhaas, M.; Meiser, M.; Bergem, S.; et al. Mitofusin 2-containing mitochondrial-reticular microdomains direct rapid cardiomyocyte bioenergetic responses via interorganelle Ca(2+) crosstalk. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Griffiths, P.G.; Burke, A.; Sellar, P.W.; Clarke, M.P.; Gnanaraj, L.; Ah-Kine, D.; Hudson, G.; Czermin, B.; Taylor, R.W.; et al. The prevalence and natural history of dominant optic atrophy due to OPA1 mutations. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1538–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Chinnery, P.F. Dominant optic atrophy: Novel OPA1 mutations and revised prevalence estimates. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, G.; Amati-Bonneau, P.; Blakely, E.L.; Stewart, J.D.; He, L.; Schaefer, A.M.; Griffiths, P.G.; Ahlqvist, K.; Suomalainen, A.; Reynier, P.; et al. Mutation of OPA1 causes dominant optic atrophy with external ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, deafness and multiple mitochondrial DNA deletions: A novel disorder of mtDNA maintenance. Brain 2008, 131 Pt 2, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Griffiths, P.G.; Gorman, G.S.; Lourenco, C.M.; Wright, A.F.; Auer-Grumbach, M.; Toscano, A.; Musumeci, O.; Valentino, M.L.; Caporali, L.; et al. Multi-system neurological disease is common in patients with OPA1 mutations. Brain 2010, 133 Pt 3, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carelli, V.; Musumeci, O.; Caporali, L.; Zanna, C.; La Morgia, C.; Del Dotto, V.; Porcelli, A.M.; Rugolo, M.; Valentino, M.L.; Iommarini, L.; et al. Syndromic parkinsonism and dementia associated with OPA1 missense mutations. Ann. Neurol. 2015, 78, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braathen, G.J.; Sand, J.C.; Lobato, A.; Høyer, H.; Russell, M.B. Genetic epidemiology of Charcot–Marie–Tooth in the general population. Eur. J. Neurol. 2010, 18, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braathen, G.J.; Sand, J.C.; Lobato, A.; Høyer, H.; Russell, M.B. MFN2 point mutations occur in 3.4% of Charcot-Marie-Tooth families. An investigation of 232 Norwegian CMT families. BMC Med. Genet. 2010, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feely, S.M.; Laura, M.; Siskind, C.E.; Sottile, S.; Davis, M.; Gibbons, V.S.; Reilly, M.M.; Shy, M.E. MFN2 mutations cause severe phenotypes in most patients with, C.M.T.2.A. Neurology 2011, 76, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Casari, G.; De Fusco, M.; Ciarmatori, S.; Zeviani, M.; Mora, M.; Fernandez, P.; De Michele, G.; Filla, A.; Cocozza, S.; Marconi, R.; et al. Spastic paraplegia and OXPHOS impairment caused by mutations in paraplegin, a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial metalloprotease. Cell 1998, 93, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfeffer, G.; Pyle, A.; Griffin, H.; Miller, J.; Wilson, V.; Turnbull, L.; Fawcett, K.; Sims, D.; Eglon, G.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; et al. SPG7 mutations are a common cause of undiagnosed ataxia. Neurology 2015, 84, 1174–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hewamadduma, C.A.; Hoggard, N.; O’Malley, R.; Robinson, M.K.; Beauchamp, N.J.; Segamogaite, R.; Martindale, J.; Rodgers, T.; Rao, G.; Sarrigiannis, P.; et al. Novel genotype-phenotype and MRI correlations in a large cohort of patients with SPG7 mutations. Neurol. Genet. 2018, 4, e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De la Casa-Fages, B.; Fernández-Eulate, G.; Gamez, J.; Barahona-Hernando, R.; Morís, G.; García-Barcina, M.; Infante, J.; Zulaica, M.; Fernández-Pelayo, U.; Muñoz-Oreja, M.; et al. Parkinsonism and spastic paraplegia type 7: Expanding the spectrum of mitochondrial Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 1547–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, D.; Lazzaro, F.; Brusco, A.; Plumari, M.; Battaglia, G.; Pastore, A.; Finardi, A.; Cagnoli, C.; Tempia, F.; Frontali, M.; et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial protease gene AFG3L2 cause dominant hereditary ataxia SCA28. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, G.S.; Pfeffer, G.; Griffin, H.; Blakely, E.L.; Kurzawa-Akanbi, M.; Gabriel, J.; Sitarz, K.; Roberts, M.; Schoser, B.; Pyle, A.; et al. Clonal expansion of secondary mitochondrial DNA deletions associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 28. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pfeffer, G.; Gorman, G.S.; Griffin, H.; Kurzawa-Akanbi, M.; Blakely, E.L.; Wilson, I.; Sitarz, K.; Moore, D.; Murphy, J.L.; Alston, C.L.; et al. Mutations in the SPG7 gene cause chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia through disordered mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Brain 2014, 137 Pt 5, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vielhaber, S.; Debska-Vielhaber, G.; Peeva, V.; Schoeler, S.; Kudin, A.P.; Minin, I.; Schreiber, S.; Dengler, R.; Kollewe, K.; Zuschratter, W.; et al. Mitofusin 2 mutations affect mitochondrial function by mitochondrial DNA depletion. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnen, P.E.; Yarham, J.W.; Besse, A.; Wu, P.; Faqeih, E.A.; Al-Asmari, A.M.; Saleh, M.A.; Eyaid, W.; Hadeel, A.; He, L.; et al. Mutations in FBXL4 cause mitochondrial encephalopathy and a disorder of mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 93, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Mauro, S.; Hirano, M.M.E.R.R.F. GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1520/ (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Sawyer, S.L.; Cheuk-Him Ng, A.; Innes, A.M.; Wagner, J.D.; Dyment, D.A.; Tetreault, M.; Majewski, J.; Boycott, K.M.; Screaton, R.A.; Nicholson, G. Homozygous mutations in MFN2 cause multiple symmetric lipomatosis associated with neuropathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 5109–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capel, E.; Vatier, C.; Cervera, P.; Stojkovic, T.; Disse, E.; Cottereau, A.S.; Auclair, M.; Verpont, M.C.; Mosbah, H.; Gourdy, P.; et al. MFN2-associated lipomatosis: Clinical spectrum and impact on adipose tissue. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018, 12, 1420–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, K.; Farh, L.; Marshall, T.K.; Deschenes, R.J. Normal mitochondrial structure and genome maintenance in yeast requires the dynamin-like product of the MGM1 gene. Curr. Genet. 1993, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, D.; Brunner, M.; Neupert, W.; Westermann, B. Fzo1p is a mitochondrial outer membrane protein essential for the biogenesis of functional mitochondria in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 20150–20155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Liu, T.; Tran, A.; Lu, X.; Tomilov, A.A.; Davies, V.; Cortopassi, G.; Chiamvimonvat, N.; Bers, D.M.; Votruba, M.; et al. OPA1 mutation and late-onset cardiomyopathy: Mitochondrial dysfunction and mtDNA instability. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012, 1, e003012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Detmer, S.A.; Ewald, A.J.; Griffin, E.E.; Fraser, S.E.; Chan, D.C. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 160, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, T.; Ishihara, T.; Kohno, H.; Saita, S.; Ichimura, A.; Maenaka, K.; Ishihara, N. Molecular basis of selective mitochondrial fusion by heterotypic action between OPA1 and cardiolipin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVay, R.M.; Dominguez-Ramirez, L.; Lackner, L.L.; Hoppins, S.; Stahlberg, H.; Nunnari, J. Coassembly of Mgm1 isoforms requires cardiolipin and mediates mitochondrial inner membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ban, T.; Heymann, J.A.; Song, Z.; Hinshaw, J.E.; Chan, D.C. OPA1 disease alleles causing dominant optic atrophy have defects in cardiolipin-stimulated GTP hydrolysis and membrane tubulation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 2113–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.Y.; Huang, P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Chan, D.C.; Schiller, J.; Frohman, M.A. A common lipid links Mfn-mediated mitochondrial fusion and SNARE-regulated exocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ban-Ishihara, R.; Tomohiro-Takamiya, S.; Tani, M.; Baudier, J.; Ishihara, N.; Kuge, O. COX assembly factor ccdc56 regulates mitochondrial morphology by affecting mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589 Pt B, 3126–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.M.; Yang, Y.; Ylikallio, E.; Khairullin, R.; Woldegebriel, R.; Lin, K.-L.; Euro, L.; Palin, E.; Wolf, A.; Trokovic, R.; et al. ATPase-deficient mitochondrial inner membrane protein ATAD3A disturbs mitochondrial dynamics in dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilquin, B.; Taillebourg, E.; Cherradi, N.; Hubstenberger, A.; Gay, O.; Merle, N.; Assard, N.; Fauvarque, M.O.; Tomohiro, S.; Kuge, O.; et al. The AAA+ ATPase ATAD3A controls mitochondrial dynamics at the interface of the inner and outer membranes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 30, 1984–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, X.; Hu, D.; Prosdocimo, D.A.; Hoppel, C.; Jain, M.K.; Ramachandran, R.; Qi, X. ATAD3A oligomerization causes neurodegeneration by coupling mitochondrial fragmentation and bioenergetics defects. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Desai, R.; Frazier, A.E.; Durigon, R.; Patel, H.; Jones, A.W.; Dalla Rosa, I.; Lake, N.J.; Compton, A.G.; Mountford, H.S.; Tucker, E.J.; et al. ATAD3 gene cluster deletions cause cerebellar dysfunction associated with altered mitochondrial DNA and cholesterol metabolism. Brain 2017, 140, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, A.C.; Strucinska, K.; Muñoz Oreja, M.; Parrish, A.; Caswell, R.; Stals, K.L.; Durigon, R.; Durlacher-Betzer, K.; Cunningham, M.H.; Grochowski, C.M.; et al. Recurrent De Novo NAHR Reciprocal Duplications in the ATAD3 Gene Cluster Cause a Neurogenetic Trait with Perturbed Cholesterol and Mitochondrial Metabolism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 106, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peralta, S.; Goffart, S.; Williams, S.L.; Diaz, F.; Garcia, S.; Nissanka, N.; Area-Gomez, E.; Pohjoismaki, J.; Moraes, C.T. ATAD3 controls mitochondrial cristae structure in mouse muscle, influencing mtDNA replication and cholesterol levels. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amati-Bonneau, P.; Valentino, M.L.; Reynier, P.; Gallardo, M.E.; Bornstein, B.; Boissiere, A.; Campos, Y.; Rivera, H.; de la Aleja, J.G.; Carroccia, R.; et al. OPA1 mutations induce mitochondrial DNA instability and optic atrophy ‘plus’ phenotypes. Brain 2008, 131 Pt 2, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lodi, R.; Tonon, C.; Valentino, M.L.; Manners, D.; Testa, C.; Malucelli, E.; La Morgia, C.; Barboni, P.; Carbonelli, M.; Schimpf, S.; et al. Defective mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate production in skeletal muscle from patients with dominant optic atrophy due to OPA1 mutations. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzier, C.; Bannwarth, S.; Chaussenot, A.; Chevrollier, A.; Verschueren, A.; Bonello-Palot, N.; Bonello-Palot, N.; Fragaki, K.; Cano, A.; Pouget, J.; et al. The MFN2 gene is responsible for mitochondrial DNA instability and optic atrophy ‘plus’ phenotype. Brain 2012, 135 Pt 1, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, T.; Robotham, J.L.; Yoon, Y. Increased production of reactive oxygen species in hyperglycemic conditions requires dynamic change of mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2653–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trifunovic, A.; Wredenberg, A.; Falkenberg, M.; Spelbrink, J.N.; Rovio, A.T.; Bruder, C.E.; Bohlooly, Y.M.; Gidlof, S.; Oldfors, A.; Wibom, R.; et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 2004, 429, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, F.; Malka, F.; Frachon, P.; Lombes, A.; Rojo, M. Organisation and dynamics of human mitochondrial DNA. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117 Pt 13, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kandul, N.P.; Zhang, T.; Hay, B.A.; Guo, M. Selective removal of deletion-bearing mitochondrial DNA in heteroplasmic Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malena, A.; Loro, E.; Di Re, M.; Holt, I.J.; Vergani, L. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission favours mutant over wild-type mitochondrial DNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 3407–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfanner, N.; Meijer, M. The Tom and Tim machine. Curr. Biol. 1997, 7, R100–R103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herrmann, J.M.; Neupert, W. Protein insertion into the inner membrane of mitochondria. IUBMB Life 2003, 55, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkens, V.; Kohl, W.; Busch, K. Restricted diffusion of OXPHOS complexes in dynamic mitochondria delays their exchange between cristae and engenders a transitory mosaic distribution. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126 Pt 1, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perkins, G.; Renken, C.; Martone, M.E.; Young, S.J.; Ellisman, M.; Frey, T. Electron tomography of neuronal mitochondria: Three-dimensional structure and organisation of cristae and membrane contacts. J. Struct. Biol. 1997, 119, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, G.; Song, J.Y.; Tarsa, L.; Deerinck, T.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Frey, T.G. Electron tomography of mitochondria from brown adipocytes reveals crista junctions. J. Bioenergy Biomembr. 1998, 30, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilkerson, R.W.; Selker, J.M.; Capaldi, R.A. The cristal membrane of mitochondria is the principal site of oxidative phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2003, 546, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stephan, T.; Roesch, A.; Riedel, D.; Jakobs, S. Live-cell STED nanoscopy of mitochondrial cristae. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jajoo, R.; Jung, Y.; Huh, D.; Viana, M.P.; Rafelski, S.M.; Springer, M.; Paulsson, J. Accurate concentration control of mitochondria and nucleoids. Science 2016, 351, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prachar, J. Ultrastructure of mitochondrial nucleoid and its surroundings. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2016, 35, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajala, N.; Gerhold, J.; Martinsson, P.; Klymov, A.; Spelbrink, J.N. Replication factors transiently associate with mtDNA at the mitochondrial inner membrane to facilitate replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 42, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khalifat, N.; Puff, N.; Bonneau, S.; Fournier, J.-B.; Angelova, M.I. Membrane Deformation under Local pH Gradient: Mimicking Mitochondrial Cristae Dynamics. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, 4924–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, A.; Barriere, S.; Broseus, L.; Brooke, J.; Lorenzi, C.; Villemin, J.P.; Beurier, G.; Sabatier, R.; Reynes, C.; Mancheron, A.; et al. GECKO is a genetic algorithm to classify and explore high throughput sequencing data. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, K.; Gohil, V.; Stuart, R.A.; Hunte, C.; Brandt, U.; Greenberg, M.L.; Schägger, H. Cardiolipin stabilizes respiratory chain supercomplexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 52873–52880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tasseva, G.; Bai, H.D.; Davidescu, M.; Haromy, A.; Michelakis, E.; Vance, J.E. Phosphatidylethanolamine Deficiency in Mammalian Mitochondria Impairs Oxidative Phosphorylation and Alters Mitochondrial Morphology. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 288, 4158–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fleischer, S.; Rouser, G.; Fleischer, B.; Casu, A.; Kritchevsky, G. Lipid composition of mitochondria from bovine heart, liver, and kidney. J. Lipid Res. 1967, 8, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gerhold, J.M.; Cansiz-Arda, S.; Lohmus, M.; Engberg, O.; Reyes, A.; van Rennes, H.; Sanz, A.; Holt, I.J.; Cooper, H.M.; Spelbrink, J.N. Human Mitochondrial DNA-Protein Complexes Attach to a Cholesterol-Rich Membrane Structure. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hung, V.; Lam, S.S.; Udeshi, N.D.; Svinkina, T.; Guzman, G.; Mootha, V.K.; Carr, S.A.; Ting, A.Y. Proteomic mapping of cytosol-facing outer mitochondrial and ER membranes in living human cells by proximity biotinylation. Elife 2017, 6, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hubstenberger, A.; Merle, N.; Charton, R.; Brandolin, G.; Rousseau, D. Topological analysis of ATAD3A insertion in purified human mitochondria. J. Bioenergy Biomembr. 2010, 42, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issop, L.; Fan, J.; Lee, S.; Rone, M.B.; Basu, K.; Mui, J.; Papadopoulos, V.; Fan, J. Mitochondria-Associated Membrane Formation in Hormone-Stimulated Leydig Cell Steroidogenesis: Role of ATAD3. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olichon, A.; Baricault, L.; Gas, N.; Guillou, E.; Valette, A.; Belenguer, P.; Lenaers, G. Loss of OPA1 perturbates the mitochondrial inner membrane structure and integrity, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 7743–7746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kasashima, K.; Sumitani, M.; Satoh, M.; Endo, H. Human prohibitin 1 maintains the organisation and stability of the mitochondrial nucleoids. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, C.; Haag, M.; Potting, C.; Rodenfels, J.; Dip, P.V.; Wieland, F.T.; Brügger, B.; Westermann, B.; Langer, T. The genetic interactome of prohibitins: Coordinated control of cardiolipin and phosphatidylethanolamine by conserved regulators in mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 184, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merkwirth, C.; Dargazanli, S.; Tatsuta, T.; Geimer, S.; Löwer, B.; Wunderlich, F.T.; von Kleist-Retzow, J.C.; Waisman, A.; Westermann, B.; Langer, T. Prohibitins control cell proliferation and apoptosis by regulating OPA1-dependent cristae morphogenesis in mitochondria. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richter-Dennerlein, R.; Korwitz, A.; Haag, M.; Tatsuta, T.; Dargazanli, S.; Baker, M.; Decker, T.; Lamkemeyer, T.; Rugarli, E.I.; Langer, T. DNAJC19, a mitochondrial cochaperone associated with cardiomyopathy, forms a complex with prohibitins to regulate cardiolipin remodeling. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolf, D.M.; Segawa, M.; Kondadi, A.K.; Anand, R.; Bailey, S.T.; Reichert, A.S.; van der Bliek, A.M.; Shackelford, D.B.; Liesa, M.; Shirihai, O.S. Individual cristae within the same mitochondrion display different membrane potentials and are functionally independent. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R.; Mourier, A.; Yamada, J.; McCaffery, J.M.; Nunnari, J. MICOS coordinates with respiratory complexes and lipids to establish mitochondrial inner membrane architecture. Elife 2015, 4, e07739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korner, C.; Barrera, M.; Dukanovic, J.; Eydt, K.; Harner, M.; Rabl, R.; Vogel, F.; Rapaport, D.; Neupert, W.; Reichert, A.S. The C-terminal domain of Fcj1 is required for formation of crista junctions and interacts with the TOB/SAM complex in mitochondria. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 2143–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glytsou, C.; Calvo, E.; Cogliati, S.; Mehrotra, A.; Anastasia, I.; Rigoni, G.; Raimondi, A.; Shintani, N.; Loureiro, M.; Vazquez, J.; et al. Optic Atrophy 1 Is Epistatic to the Core MICOS Component MIC60 in Mitochondrial Cristae Shape Control. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 3024–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Ruan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Jian, F.; Hu, C.; Miao, L.; Gong, L.; Sun, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; et al. Mic60/Mitofilin determines MICOS assembly essential for mitochondrial dynamics and mtDNA nucleoid organisation. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbot, M.; Jans, D.C.; Schulz, C.; Denkert, N.; Kroppen, B.; Hoppert, M.; Jakobs, S.; Meinecke, M. Mic10 oligomerizes to bend mitochondrial inner membranes at cristae junctions. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bohnert, M.; Zerbes, R.M.; Davies, K.M.; Muhleip, A.W.; Rampelt, H.; Horvath, S.E.; Boenke, T.; Kram, A.; Perschil, I.; Veenhuis, M.; et al. Central role of Mic10 in the mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koob, S.; Barrera, M.; Anand, R.; Reichert, A.S. The non-glycosylated isoform of MIC26 is a constituent of the mammalian MICOS complex and promotes formation of crista junctions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 1551–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weber, T.A.; Koob, S.; Heide, H.; Wittig, I.; Head, B.; van der Bliek, A.; Brandt, U.; Mittelbronn, M.; Reichert, A.S. APOOL is a cardiolipin-binding constituent of the Mitofilin/MINOS protein complex determining cristae morphology in mammalian mitochondria. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davies, K.M.; Anselmi, C.; Wittig, I.; Faraldo-Gómez, J.D.; Kühlbrandt, W. Structure of the yeast F1Fo-ATP synthase dimer and its role in shaping the mitochondrial cristae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13602–13607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paumard, P.; Vaillier, J.; Coulary, B.; Schaeffer, J.; Soubannier, V.; Mueller, D.M.; Brethes, D.; di Rago, J.P.; Velours, J. The ATP synthase is involved in generating mitochondrial cristae morphology. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eydt, K.; Davies, K.J.; Behrendt, C.; Wittig, I.; Reichert, A.S. Cristae architecture is determined by an interplay of the MICOS complex and the F1Fo ATP synthase via Mic27 and Mic10. Microb. Cell 2017, 4, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quintana-Cabrera, R.; Quirin, C.; Glytsou, C.; Corrado, M.; Urbani, A.; Pellattiero, A.; Calvo, E.; Vazquez, J.; Enriquez, J.A.; Gerle, C.; et al. The cristae modulator Optic atrophy 1 requires mitochondrial ATP synthase oligomers to safeguard mitochondrial function. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, S.; DeVay, R.; Block, J.; Cassidy-Stone, A.; Wayson, S.; McCaffery, J.M.; Nunnari, J. Mitochondrial inner-membrane fusion and crista maintenance requires the dynamin-related GTPase Mgm1. Cell 2006, 127, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cipolat, S.; Rudka, T.; Hartmann, D.; Costa, V.; Serneels, L.; Craessaerts, K.; Metzger, K.; Frezza, C.; Annaert, W.; D’Adamio, L.; et al. Mitochondrial rhomboid PARL regulates cytochrome c release during apoptosis via OPA1-dependent cristae remodeling. Cell 2006, 126, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khacho, M.; Tarabay, M.; Patten, D.; Khacho, P.; MacLaurin, J.G.; Guadagno, J.; Bergeron, R.; Cregan, S.P.; Harper, M.E.; Park, D.S.; et al. Acidosis overrides oxygen deprivation to maintain mitochondrial function and cell survival. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patten, D.A.; Wong, J.; Khacho, M.; Soubannier, V.; Mailloux, R.J.; Pilon-Larose, K.; MacLaurin, J.G.; Park, D.S.; McBride, H.M.; Trinkle-Mulcahy, L.; et al. OPA1-dependent cristae modulation is essential for cellular adaptation to metabolic demand. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2676–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Darshi, M.; Mendiola, V.L.; Mackey, M.R.; Murphy, A.N.; Koller, A.; Perkins, G.A.; Ellisman, M.H.; Taylor, S.S. ChChd3, an inner mitochondrial membrane protein, is essential for maintaining crista integrity and mitochondrial function. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 2918–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perciavalle, R.M.; Stewart, D.P.; Koss, B.; Lynch, J.; Milasta, S.; Bathina, M.; Temirov, J.; Cleland, M.M.; Pelletier, S.; Schuetz, J.D.; et al. Anti-apoptotic MCL-1 localizes to the mitochondrial matrix and couples mitochondrial fusion to respiration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Böttinger, L.; Horvath, S.E.; Kleinschroth, T.; Hunte, C.; Daum, G.; Pfanner, N.; Becker, T. Phosphatidylethanolamine and cardiolipin differentially affect the stability of mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 423, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Desmurs, M.; Foti, M.; Raemy, E.; Vaz, F.M.; Martinou, J.C.; Bairoch, A.; Lane, L. C11orf83, a mitochondrial cardiolipin-binding protein involved in bc1 complex assembly and supercomplex stabilization. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 35, 1139–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marusich, M.F.; Robinson, B.H.; Taanman, J.W.; Kim, S.J.; Schillace, R.; Smith, J.L.; Capaldi, R.A. Expression of mtDNA and nDNA encoded respiratory chain proteins in chemically and genetically-derived Rho0 human fibroblasts: A comparison of subunit proteins in normal fibroblasts treated with ethidium bromide and fibroblasts from a patient with mtDNA depletion syndrome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1362, 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, R.; Nakayama, A.; Nakase, T.; Toba, H.; Mukainaka, T.; Sakaguchi, H.; Saiwaki, T.; Sakurai, H.; Wada, M.; Fushiki, S. A newly established neuronal rho-0 cell line highly susceptible to oxidative stress accumulates iron and other metals. Relevance to the origin of metal ion deposits in brains with neurodegenerative disorders. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 41455–41462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, S.; Guha, M.; Kashina, A.; Avadhani, N.G. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial dynamics-The cancer connection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenergy 2017, 1858, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, N.G.; Wang, J.; Wilhelmsson, H.; Oldfors, A.; Rustin, P.; Lewandoski, M.; Barsh, G.S.; Clayton, D.A. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wilhelmsson, H.; Graff, C.; Li, H.; Oldfors, A.; Rustin, P.; Bruning, J.C.; Kahn, C.R.; Clayton, D.A.; Barsh, G.S.; et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and atrioventricular conduction blocks induced by heart-specific inactivation of mitochondrial DNA gene expression. Nat. Genet. 1999, 21, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wredenberg, A.; Wibom, R.; Wilhelmsson, H.; Graff, C.; Wiener, H.H.; Burden, S.J.; Oldfors, A.; Westerblad, H.; Larsson, N.G. Increased mitochondrial mass in mitochondrial myopathy mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15066–15071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.Y.; Hwang, J.M.; Ko, H.S.; Seong, M.W.; Park, B.J.; Park, S.S. Mitochondrial DNA content is decreased in autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Neurology 2005, 64, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezza, C.; Cipolat, S.; Martins de Brito, O.; Micaroni, M.; Beznoussenko, G.V.; Rudka, T.; Bartoli, D.; Polishuck, R.S.; Danial, N.N.; De Strooper, B.; et al. OPA1 controls apoptotic cristae remodeling independently from mitochondrial fusion. Cell 2006, 126, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tezze, C.; Romanello, V.; Desbats, M.A.; Fadini, G.P.; Albiero, M.; Favaro, G.; Ciciliot, S.; Soriano, M.E.; Morbidoni, V.; Cerqua, C.; et al. Age-Associated Loss of OPA1 in Muscle Impacts Muscle Mass, Metabolic Homeostasis, Systemic Inflammation, and Epithelial Senescence. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1374–1389.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, M.V.; Bette, S.; Schimpf, S.; Schuettauf, F.; Schraermeyer, U.; Wehrl, H.F.; Ruttiger, L.; Beck, S.C.; Tonagel, F.; Pichler, B.J.; et al. A splice site mutation in the murine Opa1 gene features pathology of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Brain 2007, 130 Pt 4, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rabl, R.; Soubannier, V.; Scholz, R.; Vogel, F.; Mendl, N.; Vasiljev-Neumeyer, A.; Korner, C.; Jagasia, R.; Keil, T.; Baumeister, W.; et al. Formation of cristae and crista junctions in mitochondria depends on antagonism between Fcj1 and Su e/g. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 185, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Itoh, K.; Tamura, Y.; Iijima, M.; Sesaki, H. Effects of Fcj1-Mos1 and mitochondrial division on aggregation of mitochondrial DNA nucleoids and organelle morphology. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 1842–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genin, E.C.; Plutino, M.; Bannwarth, S.; Villa, E.; Cisneros-Barroso, E.; Roy, M.; Ortega-Vila, B.; Fragaki, K.; Lespinasse, F.; Pinero-Martos, E.; et al. CHCHD10 mutations promote loss of mitochondrial cristae junctions with impaired mitochondrial genome maintenance and inhibition of apoptosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Taki, M.; Sato, Y.; Tamura, Y.; Yaginuma, H.; Okada, Y.; Yamaguchi, S. A photostable fluorescent marker for the superresolution live imaging of the dynamic structure of the mitochondrial cristae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 15817–15822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kondadi, A.K.; Anand, R.; Hänsch, S.; Urbach, J.; Zobel, T.; Wolf, D.M.; Segawa, M.; Liesa, M.; Shirihai, O.S.; Weidtkamp-Peters, S.; et al. Cristae undergo continuous cycles of membrane remodelling in a MICOS-dependent manner. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e49776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]