Unique Characteristics of Women and Infants Moderate the Association between Depression and Mother–Infant Interaction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

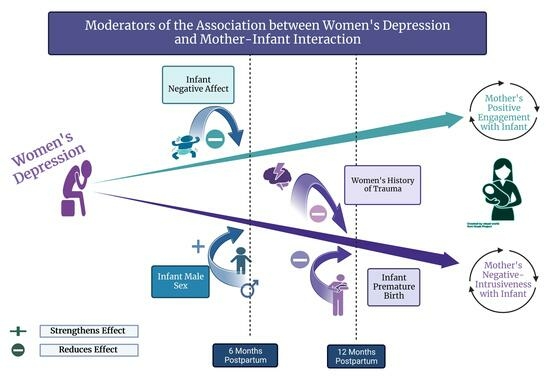

1.1. Key Moderators

1.1.1. Comorbid Anxiety

1.1.2. Exposure to Adversity

1.1.3. Infant Characteristics

Infant Sex

Temperament

Neonatal Health

1.2. Summary

1.3. Study Purpose

2. Method

2.1. Design and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Maternal Depression

2.2.2. Mother–Infant Interactions

2.2.3. Moderating Variables

Comorbid Anxiety

Exposure to Adversity

Infant Characteristics

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Bivariate Correlations

3.3. Moderators of the Relationship between Women’s Depression and Their Interactions

3.3.1. Positive Engagement at Six Months of Infant Age

3.3.2. Negative Intrusiveness at 6 Months of Infant Age

3.3.3. Mother–Infant Interactions at 12 Months of Infant Age

4. Discussion

4.1. Significant Moderators

4.1.1. Infant Sex

4.1.2. Infant Temperament

4.1.3. Neonatal Health

4.1.4. History of Trauma

4.2. Candidate Moderators That Were Not Significant

4.2.1. Anxiety

4.2.2. Poverty

4.3. Covariates: Maternal Age and Education

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

4.5. Implications for Research and Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kingston, D.; Kehler, H.; Austin, M.-P.; Mughal, M.K.; Wajid, A.; Vermeyden, L.; Benzies, K.; Brown, S.; Stuart, S.; Giallo, R. Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the first 12 months postpartum and child externalizing and internalizing behavior at three years. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubotzky-Gete, S.; Ornoy, A.; Grotto, I.; Calderon-Margalit, R. Postpartum depression and infant development up to 24 months: A nationwide population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 285, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women Health 2019, 15, 1745506519844044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Manian, N.; Henry, L.M. Clinically depressed and typically developing mother–infant dyads: Domain base rates and correspondences, relationship contingencies and attunement. Infancy 2021, 26, 877–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.H.; Simon, H.F.M.; Shamblaw, A.L.; Kim, C.Y. Parenting as a Mediator of Associations between Depression in Mothers and Children’s Functioning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 427–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, H.; Flykt, M.; Sinervä, E.; Nolvi, S.; Kataja, E.L.; Pelto, J.; Karlsson, H.; Karlsson, L.; Korja, R. How maternal pre- and postnatal symptoms of depression and anxiety affect early mother-infant interaction? J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 257, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.C.; Zayas, L.H.; McKee, M. Mother-Infant Interaction, Life Events and Prenatal and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms Among Urban Minority Women in Primary Care. Matern. Child Health J. 2006, 10, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dau, A.L.B.T.B.T.; Callinan, L.S.; Smith, M.V. An examination of the impact of maternal fetal attachment, postpartum depressive symptoms and parenting stress on maternal sensitivity. Infant Behav. Dev. 2019, 54, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, H.; Owais, S.; Savoy, C.D.; Van Lieshout, R.J. Depression, anxiety, and mother-infant bonding in women seeking treatment for postpartum depression before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, 35146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Kunz, E.; Schweyer, D.; Eickhorst, A.; Cierpka, M. Links between maternal postpartum depressive symptoms, maternal distress, infant gender and sensitivity in a high-risk population. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2011, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H. Determinants of Parenting. In Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Resilience, and Intervention, 3rd ed.; Cicchetti, D., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 4, pp. 180–270. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, G.; Girshovitz, I.; Marcus, K.; Zhang, Y.; Pathak, J.; Bar, V.; Akiva, P. Estimation of postpartum depression risk from electronic health records using machine learning. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, E.; Feldman, B.; Weizman, A.; Krivoy, A.; Gur, S.; Barzilay, E.; Gabay, H.; Levy, J.; Levinkron, O.; Lawrence, G. Development and validation of a machine learning-based postpartum depression prediction model: A nationwide cohort study. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S.H.; Bakeman, R.; McCallum, M.; Rouse, M.H.; Thompson, S.F. Extending Models of Sensitive Parenting of Infants to Women at Risk for Perinatal Depression. Parenting 2017, 17, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, C.; Tietz, A.; Müller, M.; Seibold, K.; Tronick, E. The impact of maternal anxiety disorder on mother-infant interaction in the postpartum period. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, M.; Giallo, R.; Cooklin, A.; Dunning, M. Maternal anxiety, risk factors and parenting in the first post-natal year. Child Care Health Dev. 2014, 41, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.J.; Flynn, H.; Christian, L.; Hantsoo, L.; di Scalea, T.L.; Kornfield, S.L.; Muzik, M.; Simeonova, D.I.; Cooper, B.A.; Strahm, A.; et al. Symptom profiles of women at risk of mood disorders: A latent class analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.J.; Simeonova, D.I.; Kimmel, M.C.; Battle, C.L.; Maki, P.M.; Flynn, H.A. Anxiety and physical health problems increase the odds of women having more severe symptoms of depression. Arch. Women Ment. Health 2016, 19, 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, S.L.; Dietz, P.M.; O’Hara, M.W.; Burley, K.; Ko, J.Y. Postpartum anxiety and comorbid depression in a population-based sample of women. J. Women Health 2014, 23, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer-Brody, S.; Howard, L.M.; Bergink, V.; Vigod, S.; Jones, I.; Munk-Olsen, T.; Honikman, S.; Milgrom, J. Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 18022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Cooklin, A.R.; Leach, L.S. Comorbid anxiety and depression: A community-based study examining symptomology and correlates during the postpartum period. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2019, 37, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, E.; Agostini, F.; Salvatori, P.; Biasini, A.; Monti, F. Mother-preterm infant interactions at 3 months of corrected age: Influence of maternal depression, anxiety and neonatal birth weight. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, S.J.; Leung, C. Maternal depressive symptoms, poverty, and young motherhood increase the odds of early depressive and anxiety disorders for children born prematurely. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 42, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, R.E.; Finegood, E.D.; Braren, S.H.; Dejoseph, M.L.; Putrino, D.F.; Wilson, D.A.; Sullivan, R.M.; Raver, C.C.; Blair, C. Developing a neurobehavioral animal model of poverty: Drawing cross-species connections between environments of scarcity-adversity, parenting quality, and infant outcome. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grekin, R.; Brock, R.L.; O’hara, M.W. The effects of trauma on perinatal depression: Examining trajectories of depression from pregnancy through 24 months postpartum in an at-risk population. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 218, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, W.; Muzik, M.; McGinnis, E.; Hamilton, L.; Menke, R.; Rosenblum, K. Comorbid trajectories of postpartum depression and PTSD among mothers with childhood trauma history: Course, predictors, processes and child adjustment. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 200, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, J.S.; Sperlich, M.; Low, L.K.; Ronis, D.L.; Muzik, M.; Liberzon, I. Childhood Abuse History, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Postpartum Mental Health, and Bonding: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Midwifery Women Health 2013, 58, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, N.; Julian, M.; Muzik, M. Perinatal depression, PTSD, and trauma: Impact on mother–infant attachment and interventions to mitigate the transmission of risk. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2019, 31, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronick, E.; Reck, C. Infants of Depressed Mothers. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M.; Olson, K.; Beeghly, M.; Tronick, E. Making up is hard to do, especially for mothers with high levels of depressive symptoms and their infant sons. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Holditch-Davis, D.; Miles, M. Effects of maternal depressive symptoms and infant gender on the interactions between mothers and their medically at-risk infants. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2008, 37, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spry, E.A.; Aarsman, S.R.; Youssef, G.J.; Patton, G.C.; Macdonald, J.A.; Sanson, A.; Thomson, K.; Hutchinson, D.M.; Letcher, P.; Olsson, C.A. Maternal and paternal depression and anxiety and offspring infant negative affectivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Rev. 2020, 58, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulussen-Hoogeboom, M.C.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Hermanns, J.M.A.; Peetsma, T.T.D. Child negative emotionality and parenting from infancy to preschool: A meta-analytic review. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dix, T.; Yan, N. Mothers’ depressive symptoms and infant negative emotionality in the prediction of child adjustment at age 3: Testing the maternal reactivity and child vulnerability hypotheses. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, M.H.; Goodman, S.H. Perinatal depression influences on infant negative affectivity: Timing, severity, and co-morbid anxiety. Infant Behav. Dev. 2014, 37, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, C.; De Carli, P.; Vieno, A.; Piallini, G.; Zoia, S.; Simonelli, A. Does infant negative emotionality moderate the effect of maternal depression on motor development? Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 119, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiff, C.J.; Lengua, L.J.; Zalewski, M. Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 251–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, S.T.; Leve, L.D.; Harold, G.T.; Neiderhiser, J.M.; Shaw, D.S.; Ge, X.; Reiss, D. Trajectories of Parenting and Child Negative Emotionality During Infancy and Toddlerhood: A Longitudinal Analysis. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 1661–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shovers, S.M.; Bachman, S.S.; Popek, L.; Turchi, R.M. Maternal postpartum depression: Risk factors, impacts, and interventions for the NICU and beyond. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2021, 33, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, A.T.F.; Lasiuk, G.C.; Radünz, V.; Hegadoren, K. Scoping Review of the Mental Health of Parents of Infants in the NICU. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 46, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunberg, V.A.; Geller, P.A.; Bonacquisti, A.; Patterson, C.A. NICU infant health severity and family outcomes: A systematic review of assessments and findings in psychosocial research. J. Perinatol. 2019, 39, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionio, C.; Lista, G.; Mascheroni, E.; Olivari, M.G.; Confalonieri, E.; Mastrangelo, M.; Brazzoduro, V.; Balestriero, M.A.; Banfi, A.; Bonanomi, A.; et al. Premature birth: Complexities and difficulties in building the mother–child relationship. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2017, 35, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, C.; Soares, I.; Mesman, J. Controlling Parenting Behaviors in Parents of Children Born Preterm: A Meta-Analysis. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd ed.; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Garbin, M. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 8, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.T.; Gable, R.K. Postpartum Depression Screening Scale: Development and psychometric testing. Nurs. Res. 2000, 49, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Adamson, L.B.; Bakeman, R.; Owen, M.T.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Pace, A.; Yust, P.K.S.; Suma, K. The contribution of early communication quality to low-income children’s language success. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Child care and mother-child interaction in the first 3 years of life. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 1399–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R. The Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment: Instrument and Manual; University of Wisconsin Medical School, Department of Psychiatry: Madison, WI, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni, A.S.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Mother–Child Interactions in Early Head Start: Age and Ethnic Differences in Low-Income Dyads. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2013, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R. The parent-child Early Relational Assessment: A factorial validity study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1999, 59, 821–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Tluczek, A.; Brown, R. A mother-infant therapy group model for postpartum depression. Infant Ment. Health J. 2008, 29, 514–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unternaehrer, E.; Cost, K.T.; Bouvette-Turcot, A.; Gaudreau, H.; Massicotte, R.; Dhir, S.K.; Dass, S.A.H.; O’Donnell, K.J.; Gordon-Green, C.; Atkinson, L.; et al. Dissecting maternal care: Patterns of maternal parenting in a prospective cohort study. J. Neuroendocr. 2019, 31, e12784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S.H.; Muzik, M.; Simeonova, D.I.; Kidd, S.A.; Owen, M.T.; Cooper, B.; Kim, C.Y.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Weiss, S.J. Maternal interaction with infants among women at elevated risk for postpartum depression. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 737513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (STAI-AD); Database Record; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- First, M.; Williams, J.; Karg, R.; Spitzer, R. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research Version; SCID-5-RV); American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Poverty Guidelines. 2021. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references/2021-poverty-guidelines (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Bernstein, D.; Fink, L.; Handelsman, L.; Foote, J.; Lovejoy, M.; Wenzel, K.; Sapareto, E.; Ruggiero, J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.; Chelminski, I. A scale to screen for DSM-IV Axis I disorders in psychiatric out-patients: Performance of the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.; Anda, R.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.; Spitz, A.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M. The relationship of adult health status to childhood abuse and household dysfunction. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S.P.; Rothbart, M.K. Development of short and very short forms of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. J. Personal. Assess. 2006, 87, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S.P.; Helbig, A.L.; Gartstein, M.A.; Rothbart, M.K.; Leerkes, E. Development and Assessment of Short and Very Short Forms of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised. J. Pers. Assess. 2014, 96, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.; Wilson, C. Women with a history of postpartum affective disorder at increased risk of recurrence in future pregnancies. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planalp, E.M.; Nowak, A.L.; Tran, D.; Lefever, J.B.; Braungart-Rieker, J.M. Positive parenting, parenting stress, and child self-regulation patterns differ across maternal demographic risk. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C.; Troutman, B. Social support, infant temperament, and parenting self-efficacy: A mediational model of postpartum depression. Child Dev. 1986, 57, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, R.P.; Parade, S.H.; Dickstein, S.; Seifer, R. The association between maternal depression and sensitivity: Child-directed effects on parenting during infancy. Infant Behav. Dev. 2016, 45, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, F.; Neri, E.; Dellabartola, S.; Biasini, A.; Monti, F. Early interactive behaviours in preterm infants and their mothers: Influences of maternal depressive symptomatology and neonatal birth weight. Infant Behav. Dev. 2014, 37, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondwe, K.; Yang, Q.; White-Traut, R.; Holditch-Davis, D. Maternal psychological distress and mother-infant relationship: Multiple-birth versus singleton preterm infants. Neonatal Netw. 2017, 36, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, L.J.; Benzies, K.M.; Barnard, C.; Hayden, K.A. A scoping review of parental experiences caring for their hospitalised medically fragile infants. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.; Gee, G.; Harfield, S.; Campbell, S.; Brennan, S.; Clark, Y.; Mensah, F.; Arabena, K.; Herrman, H.; Brown, S. Parenting after a history of childhood maltreatment: A scoping review and map of evidence in the perinatal period. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofton, E.; Zhang, Y.; Green, T. Inoculation stress hypothesis of environmental enrichment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 49, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorsandi, M.; Vakilian, K.; Salehi, B.; Goudarzi, M.T.; Abdi, M. The effects of stress inoculation training on perceived stress in pregnant women. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 2977–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.; Liu, C.; Schaer, M.; Parker, K.J.; Ottet, M.-C.; Epps, A.; Buckmaster, C.L.; Bammer, R.; Moseley, M.E.; Schatzberg, A.F.; et al. Prefrontal plasticity and stress inoculation-induced resilience. Dev. Neurosci. 2009, 31, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, D.M.; Parker, K.J.; Katz, M.; Schatzberg, A.F. Developmental cascades linking stress inoculation, arousal regulation, and resilience. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, L.; Tedeschi, R. Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amore, C.; Martin, S.; Wood, K.; Brooks, C. Themes of healing and posttraumatic growth in women survivors’ narratives of intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP2697–NP2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggisberg, M.; Bottino, S.; Doran, C.M. Women’s contexts and circumstances of posttraumatic growth after sexual victimization: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 699288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol-Harper, R.; Harvey, A.G.; Stein, A. Interactions between mothers and infants: Impact of maternal anxiety. Infant Behav. Dev. 2007, 30, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, E.; Padovani, F.; Perosa, G. Mother-child interaction: Implications of chronic maternal anxiety and depression. Psychol. Res. Rev. 2019, 32, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaitz, M.; Maytal, H.; Devor, N.; Bergman, L.; Mankuta, D. Maternal anxiety, mother-infant interactions, and infants’ response to challenge. Infant Behav. Dev. 2010, 33, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, R.F.; Omar, M.A.; McKelvey, L.M. Mother-infant interaction in low-income families. Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2003, 28, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, K. Are poor parents poor parents? The relationship between poverty and parenting among mothers in the UK. Sociology 2020, 55, 349–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalil, A.; Ryan, R.; Corey, M. Diverging destinies: Maternal education and the developmental gradient in time with children. Demography 2012, 49, 1361–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, M.L.; Pan, B.A.; Ayoub, C. Predictors of Variation in Maternal Talk to Children: A Longitudinal Study of Low-Income Families. Parenting 2005, 5, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, H.J.V.; Maupin, A.N.; Landi, N.; Potenza, M.N.; Mayes, L.C. Parental reflective functioning and the neural correlates of processing infant affective cues. Soc. Neurosci. 2017, 12, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, A.; Calkins, S.D.; Bell, M.A. Longitudinal associations between the quality of mother-infant interactions and brain development across infancy. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1159–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camberis, A.L.; McMahon, C.; Gibson, F.; Boivin, J. Maternal age, psychological maturity, parenting cognitions, and mother–infant interaction. Infancy 2016, 21, 396–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G.J.; Lee, K.; Rosales-Rueda, M.; Kalil, A. Maternal age and child development. Demography 2018, 55, 2229–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.; Putnick, D.; Suwalsky, J.; Gini, M. Maternal chronological age, prenatal and perinatal history, social support, and parenting of infants. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 875–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, M.; Poehlmann, J.; Bolt, D. Predictors of parenting stress trajectories in premature infant–mother dyads. J. Fam. Psychol. 2013, 27, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Sociodemographic Characteristics | 6 Months | 12 Months |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Maternal Age | 31.3 (5.9) | 32.2 (5.2) |

| Highest Level of Education | N (%) | N (%) |

| Less than High School (HS) | 50 (7.7) | 5 (1.4) |

| HS Graduate or GED | 49 (7.5) | 19 (5.3) |

| Some College/Vocational/Other Post-HS | 136 (21.1) | 73 (20.3) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 195 (30.1) | 125 (34.8) |

| Post-Graduate | 217 (33.6) | 137 (38.2) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White/European American | 427 (66.1) | 272 (75.6) |

| Black/African American | 97 (15.0) | 45 (12.5) |

| Hispanic/Latina | 64 (9.8) | 14 (3.9) |

| Asian Americanth | 37 (5.7) | 20 (5.8) |

| More than One Race | 22 (3.4) | 9 (2.5) |

| Partner Status | ||

| Married/Living with Partner | 566 (87.5) | 337 (93.4) |

| Single/Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 81 (12.5) | 24 (6.6) |

| Poverty Level | ||

| Below Poverty Level | 112 (17.3) | 33 (9.2) |

| Maternal Clinical Status and History | 6 Months | 12 Months |

| Depression | N (%) | N (%) |

| Minimal/No Depression | 378 (58.4) | 247 (71.4) |

| Mild | 124 (19.2) | 52 (15.0) |

| Moderate | 95 (14.7) | 27 (7.8) |

| Severe | 50 (7.7) | 20 (5.8) |

| Met Threshold for Clinical Anxiety | 188 (29.1) | 97 (28.0) |

| History of Physical or Sexual Abuse | 212 (32.9) | 108 (31.5) |

| Infant Characteristics | 6 Months | 12 Months |

| Sex | N (%) | N (%) |

| Male | 323 (49.9) | 182 (49.1) |

| Female | 324 (50.1) | 189 (50.9) |

| Apgar Score < 7 | 61 (9.4) | 7 (2.4) |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Birthweight in Grams | 2973.1 (952.7) | 3290.1 (580.2) |

| Gestational Age in Weeks | 36.7 (4.1) | 37.7 (3.4) |

| Temperament (Negative Affectivity) | 3.66 (0.90) | 4.17 (0.92) |

| Mother–Infant Interaction | ||

| Positive Engagement | 3.58 (0.61) | 3.56 (0.60) |

| Negative Intrusiveness | 1.50 (0.68) | 1.34 (0.52) |

| Moderators | Depression at 6 Months PP | Depression at 12 Months PP |

|---|---|---|

| Woman’s Anxiety | ||

| 6 Months PP | 0.32 ** | 0.23 ** |

| 12 Months PP | 0.16 ** | 0.29 ** |

| Exposure to Adversity | ||

| Poverty | 0.19 ** | 0.26 ** |

| Trauma | 0.09 | 0.24 ** |

| Infant Characteristics | ||

| Sex (M) | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| Apgar < 7 | 0.26 ** | −0.07 |

| Birthweight | −0.25 ** | 0.02 |

| Gestational Age | −0.23 ** | 0.07 |

| Negative Affectivity | ||

| 6 Months PP | 0.17 ** | 0.18 ** |

| 12 Months PP | 0.06 | 0.18 ** |

| Covariates | ||

| Woman’s Age | −0.24 ** | −0.13 |

| No Partner | 0.23 ** | −0.27 ** |

| Woman’s Education | −0.29 ** | −0.19 |

| 6 Months Postnatal | 12 Months Postnatal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Engagement | Negative Intrusiveness | Positive Engagement | Negative Intrusiveness | |

| Depression | −0.08 | 0.18 ** | 0.05 | 0.12 ** |

| Moderators | ||||

| Woman’s Anxiety | ||||

| 6 Months PN | −0.12 * | 0.03 | −0.30 ** | 0.12 * |

| 12 Months PN | −0.11 ** | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| Exposure to Adversity | ||||

| Poverty | 0.19 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.09 | 0.21 ** |

| Trauma | −0.03 | 0.11 * | −0.01 | 0.08 |

| Infant Characteristics | ||||

| Sex (M) | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.12 * | −0.03 |

| Apgar < 7 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.07 |

| Birthweight | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.07 |

| Gestational Age | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.13 * | 0.02 |

| Negative Affectivity | ||||

| 6 Months PN | −0.10 * | 0.08 | −0.13 * | 0.12 * |

| 12 Months PN | −0.05 | 0.14 * | −0.06 | 0.05 |

| Covariates | ||||

| Woman’s Age | 0.15 * | −0.19 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.25 ** |

| No Partner | −0.16 * | 0.20 ** | −0.11 * | 0.23 ** |

| Years of Education | 0.22 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.21 ** |

| Coefficient | SE | p-Value | 95% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Engagement Mother | ||||

| Depression Severity | −0.034 | 0.05 | 0.530 | −0.138, 0.071 |

| Education Level | 0.135 | 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.054, 0.217 |

| Poverty | −0.500 | 0.15 | 0.001 | −0.803, −0.198 |

| Infant | ||||

| Sex | −0.182 | 0.08 | 0.028 | −0.345, −0.020 |

| Gestational Age | −0.021 | 0.01 | 0.058 | −0.043, 0.001 |

| Negative Affectivity | −0.089 | 0.05 | 0.070 | −0.184, 0.007 |

| Interactions | ||||

| Depression × Negative Affectivity | −0.100 | 0.05 | 0.039 | −0.195, −0.005 |

| Negative Intrusiveness Mother | ||||

| Depression Severity | 0.207 | 0.07 | 0.002 | 0.075, 0.340 |

| Poverty | 1.022 | 0.19 | 0.000 | 0.653, 1.390 |

| Infant | ||||

| Sex | 0.216 | 0.11 | 0.044 | 0.006, 0.426 |

| Interactions | ||||

| Depression × Sex | 0.233 | 0.12 | 0.047 | 0.003, 0.462 |

| Coefficient | SE | p-Value | 95% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Engagement Mother | ||||

| Depression Severity | 0.042 | 0.06 | 0.523 | −0.087, 0.171 |

| Age | 0.044 | 0.01 | 0.000 | 0.020, 0.067 |

| Negative Intrusiveness Mother | ||||

| Depression Severity | 0.042 | 0.13 | 0.759 | −0.310, 0.226 |

| Age | −0.078 | 0.02 | 0.000 | −0.115, −0.041 |

| History of Trauma | 0.045 | 0.21 | 0.831 | −0.365, 0.454 |

| Infant | ||||

| Gestational Age | 0.016 | 0.02 | 0.522 | −0.034, 0.067 |

| Interactions | ||||

| Depression × Trauma | −0.662 | 0.26 | 0.013 | −1.184, −0.141 |

| Depression × GA | 0.136 | 0.05 | 0.009 | 0.003, 0.239 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weiss, S.J.; Goodman, S.H.; Kidd, S.A.; Owen, M.T.; Simeonova, D.I.; Kim, C.Y.; Cooper, B.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Muzik, M. Unique Characteristics of Women and Infants Moderate the Association between Depression and Mother–Infant Interaction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5503. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175503

Weiss SJ, Goodman SH, Kidd SA, Owen MT, Simeonova DI, Kim CY, Cooper B, Rosenblum KL, Muzik M. Unique Characteristics of Women and Infants Moderate the Association between Depression and Mother–Infant Interaction. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(17):5503. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175503

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeiss, Sandra J., Sherryl H. Goodman, Sharon A. Kidd, Margaret Tresch Owen, Diana I. Simeonova, Christine Youngwon Kim, Bruce Cooper, Katherine L. Rosenblum, and Maria Muzik. 2023. "Unique Characteristics of Women and Infants Moderate the Association between Depression and Mother–Infant Interaction" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 17: 5503. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175503