- 1Department of Microbiology, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 2Department of Stomatology, School of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 3Department of Immunology, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Probiotics may be considered as an additional strategy to achieve a balanced microbiome in periodontitis. However, the mechanisms underlying the use of probiotics in the prevention or control of periodontitis are still not fully elucidated. This in vitro study aimed to evaluate the effect of two commercially available strains of lactobacilli on gingival epithelial cells (GECs) challenged by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. OBA-9 GECs were infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans strain JP2 at an MOI of 1:100 and/or co-infected with Lactobacillus acidophilus La5 (La5) or Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Lr32 (Lr32) at an MOI of 1:10 for 2 and 24 h. The number of adherent/internalized bacteria to GECs was determined by qPCR. Production of inflammatory mediators (CXCL-8, IL-1β, GM-CSF, and IL-10) by GECs was determined by ELISA, and the expression of genes encoding cell receptors and involved in apoptosis was determined by RT-qPCR. Apoptosis was also analyzed by Annexin V staining. There was a slight loss in OBA-9 cell viability after infection with A. actinomycetemcomitans or the tested probiotics after 2 h, which was magnified after 24-h co-infection. Adherence of A. actinomycetemcomitans to GECs was 1.8 × 107 (± 1.2 × 106) cells/well in the mono-infection but reduced to 1.2 × 107 (± 1.5 × 106) in the co-infection with Lr32 and to 6 × 106 (± 1 × 106) in the co-infection with La5 (p < 0.05). GECs mono-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans produced CXCL-8, GM-CSF, and IL-1β, and the co-infection with both probiotic strains altered this profile. While the co-infection of A. actinomycetemcomitans with La5 resulted in reduced levels of all mediators, the co-infection with Lr32 promoted reduced levels of CXCL-8 and GM-CSF but increased the production of IL-1β. The probiotics upregulated the expression of TLR2 and downregulated TLR4 in cells co-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans. A. actinomycetemcomitans-induced the upregulation of NRLP3 was attenuated by La5 but increased by Lr32. Furthermore, the transcription of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL-2 was upregulated, whereas the pro-apoptotic BAX was downregulated in cells co-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans and the probiotics. Infection with A. actinomycetemcomitans induced apoptosis in GECs, whereas the co-infection with lactobacilli attenuated the apoptotic phenotype. Both tested lactobacilli may interfere in A. actinomycetemcomitans colonization of the oral cavity by reducing its ability to interact with gingival epithelial cells and modulating cells response. However, L. acidophilus La5 properties suggest that this strain has a higher potential to control A. actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontitis than L. rhamnosus Lr32.

Introduction

Periodontitis is triggered by a polymicrobial community unbalanced with the host immune response, leading to chronic inflammation (Hajishengallis and Lamont, 2012; Wang, 2015). In periodontal health, the dynamic host–bacteria environment is able to maintain a beneficial commensal microbiota while preventing the emergence of opportunistic pathogens from within these established biofilms (Roberts and Darveau, 2002). However, certain species such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans play a key role in disrupting the biofilm associated with health, leading to the emergence of inflammophilic organisms, and increasing the virulence potential of the dysbiotic microbiota (Lamont and Hajishengallis, 2015).

Due to the essential role of the microbiota in host protection, the recovery of the microbial balance by the colonization of beneficial organisms associated with health appears as an attractive proposal in the prevention or as an adjuvant to the treatment of periodontitis (Raff and Hunt, 2012). Probiotics are “living microorganisms that, when given in adequate amounts, confer health benefits to the host (FAO/WHO, 2002).” These beneficial organisms may affect the microbiota by producing compounds with antimicrobial activity, competing for nutrients or adhesion sites, and altering the expression of virulence factors. They may also modulate the immune response, decrease permeability and bacterial translocation throughout epithelial barriers, and provide bioactive or regulatory metabolites (de Vrese et al., 2006; Mao et al., 2016; Matsubara et al., 2017; Albuquerque-Souza et al., 2018). Systematic reviews indicated that probiotic lactobacilli have the potential to improve periodontal conditions (Teughels et al., 2011; Matsubara et al., 2016). However, their mechanisms are still not fully elucidated.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans has been associated with periodontitis formerly known as localized aggressive periodontitis (American Academy of Periodontology [AAP], 2001), now named periodontitis of the molar–incisor pattern (MIP) (Tonetti et al., 2018). The abundance of this species is 50 times higher in periodontal sites of MIP than in healthy subjects (Amado et al., 2020), and specially, the highly leukotoxic JP2 clone can trigger rapid periodontal destruction (Anders and Haubek, 2014). This species induces the production of inflammatory mediators by gingival epithelial cells (Umeda et al., 2012) and evades the immune response by internalizing in non-phagocytic cells and producing virulence factors such as a leukotoxin and a cytolethal distending toxin (Mayer et al., 1999; Kajiya et al., 2011; Shenker et al., 2016). A. actinomycetemcomitans is acquired in the oral microbiome early in life (Lamell et al., 2000), and the colonization of the oral cavity by this species, especially of the JP2 clone, may induce a precocious alveolar bone loss (Bueno et al., 1998; Haubek et al., 2004). Hence, the exposure of infected subjects to probiotics that limit A. actinomycetemcomitans overgrowth and modulate the inflammatory response may prevent the clinical alveolar bone loss and control its progression in A. actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontitis. We have previously shown that A. actinomycetemcomitans biofilm formation and virulence may be impaired by probiotic lactobacilli (Ishikawa et al., 2021). However, little is known about the ability of probiotic strains to modulate the immune–inflammatory response induced by A. actinomycetemcomitans. Therefore, the purpose of this in vitro study was to evaluate the effect of two commercially available strains of lactobacilli on gingival epithelial cells (GECs) challenged by A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The effects of lactobacilli probiotics on GECs infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans (strain JP2) were determined on cells viability, the adhesion of A. actinomycetemcomitans or probiotics, the release of cytokines in cells supernatants, and gene expression. All experiments consisted of six groups performed in triplicates: negative control (OBA-9 cells), positive control (OBA-9 cells co-cultured with A. actinomycetemcomitans JP2), probiotic controls (OBA-9 cells co-cultured with Lactobacillus acidophilus La5 or Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Lr32), and test groups (OBA-9 cells co-cultured with A. actinomycetemcomitans JP2 and L. acidophilus La5 or L. rhamnosus Lr 32). At least two independent assays were performed.

Microorganisms and Culture Conditions

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans strain JP2 (Tsai et al., 1984), L. rhamnosus Lr32™ (DuPont™ and Danisco®, Madison, WI, United States), and L. acidophilus La5™ (CHR Hansen Holding A/S, Hørsholm, Denmark) were used for this study. Before the experiments, the strains were stored in 20% glycerol at −80°C.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans was grown in 5% CO2 (microaerophilic conditions) at 37°C in tryptic soy agar with 0.6% yeast extract (TSYE, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, United States) and in the brain–heart infusion broth (BHI; Difco). Lactobacilli were also cultivated under microaerophilic conditions in Lactobacilli MRS broth and agar (Lactobacilli MRS, Difco). Bacteria were grown in liquid media until the mid-log phase. Then, the suspensions were adjusted to an OD490nm ∼ 0.3 for A. actinomycetemcomitans, corresponding to 1 × 108 CFU/mL, and to an OD590nm ∼ 0.9 for both lactobacilli, corresponding to 2 × 108 CFU/mL.

Cell Culture

Immortalized human gingival epithelial cells (OBA-9) (Kajiya et al., 2011) were cultured at 37°C in 10% CO2 in the serum-free keratinocyte medium (KSFM-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States), supplemented with human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF), PenStrep GIBCO™ (penicillin: 10,000 units⋅mL–1/streptomycin: 10,000 μg⋅mL–1), and 25 μg/mL of amphotericin B (Invitrogen).

Co-culture Assay

OBA-9 cells (∼2 × 105 cells/well) were inoculated in 24-well tissue culture plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, United States) and incubated for 24 h to reach a semiconfluent monolayer (∼3 × 105 cells/well) in KSFM. Before the infection, the wells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.5, 0.8% NaCl). Mid-log A. actinomycetemcomitans culture in BHI broth was harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in antibiotic-free KSFM, and inoculated in OBA-9 cell monolayers at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100:1 (bacteria/eukaryotic cell). Mid-log lactobacilli cultures in MRS broth were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in antibiotic-free KSFM, and inoculated in OBA-9 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 (bacteria/eukaryotic cell). After 2 h of incubation, cells were either collected or washed with PBS and fresh medium was added, completing 24 h of incubation.

Cell Viability

Cell viability was estimated by trypan blue exclusion assay. Cells were released with Accutase® Cell Detachment Solution (BioLegend), and cell counting was performed using the Countess Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen).

Adhesion Assay

After 2 h of incubation, non-adherent bacterial cells were removed by washing with PBS (pH 7.5, 0.8% NaCl). Then, the eukaryotic cells were subjected to osmotic lysis with 1 mL of sterile water for 20 min. Analysis of the number of adherent/internalized bacteria was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), according to Ando-Suguimoto et al. (2014). Total DNA extraction was performed using the (Master Pure™ DNA Purification Kit, Epicenter, Madison, WI, United States).

Quantitative analysis was performed by comparing the CT from each sample with standard curve data obtained with template DNA of 16S rRNA A. actinomycetemcomitans, L. acidophilus La5, or L. rhamnosus Lr32 in recombinant plasmids [1500 bp of 16S rRNA of each studied strain inserted in qPCR 2.1 TOPO TA® vector, Invitrogen].

The reactions consisted of 5 μL of SYBR Green, 1 μL of template DNA, and 0.25 pmol of each species-specific stock solution primer (Table 1) to a final volume of 10 μL. The reaction was performed in 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 65°C for 1 min, 81°C for 10 s, followed by two stages at 95°C for 15 s and 65°C for 1 min, and one final stage at 0.5–95°C for 10 s. The number of microorganisms was calculated assuming six copies of 16S rRNA/chromosome for A. actinomycetemcomitans, five copies of L. rhamnosus Lr32, and four copies of L. acidophilus La51. Data were expressed as the number of cells/well.

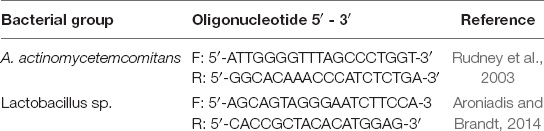

Table 1. 16S rRNA primer sequences for a quantitative analysis by qPCR of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and lactobacilli.

Quantification of Inflammatory Mediators

Levels of interleukin (IL) 1β, IL-10, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL-8), and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were determined in cells supernatants of 2- and 24-h co-culture assays by ELISA (BD Systems®) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The reading was performed on a microplate reader (Model 680, cat. 1681000, BioRad, Tokyo, Japan) adjusted at a wavelength of 450 nm, and data were expressed as pg/mL.

Gene Expression

The relative gene expression of OBA-9 cells was determined by reverse transcription followed by quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR). After 24 h of co-culture, OBA-9 cells were lysed, and total RNA was extracted using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript VILO MasterMix (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, United States). Relative expression levels were evaluated by PCR in a TaqMan Gene Expression Master system (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA, United States), using 200 ng of cDNA and TaqMan primers and probes for TLR2 (Hs00152932_m1), TLR4 (Hs01060206_m1), NLRP3 (Hs00918082_m1), BCL2 (Hs00608023_m1), BAX (Hs00180269_m1), and GAPDH (Hs02758991_gl). The qPCR comprised an initial step of 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 50°C for 1 min using the Step One Plus System (Applied Biosciences). All data were normalized to GAPDH transcript levels in the same cDNA set, and relative expression analysis was performed by the 2–ΔΔCT method (Pfaffl, 2001).

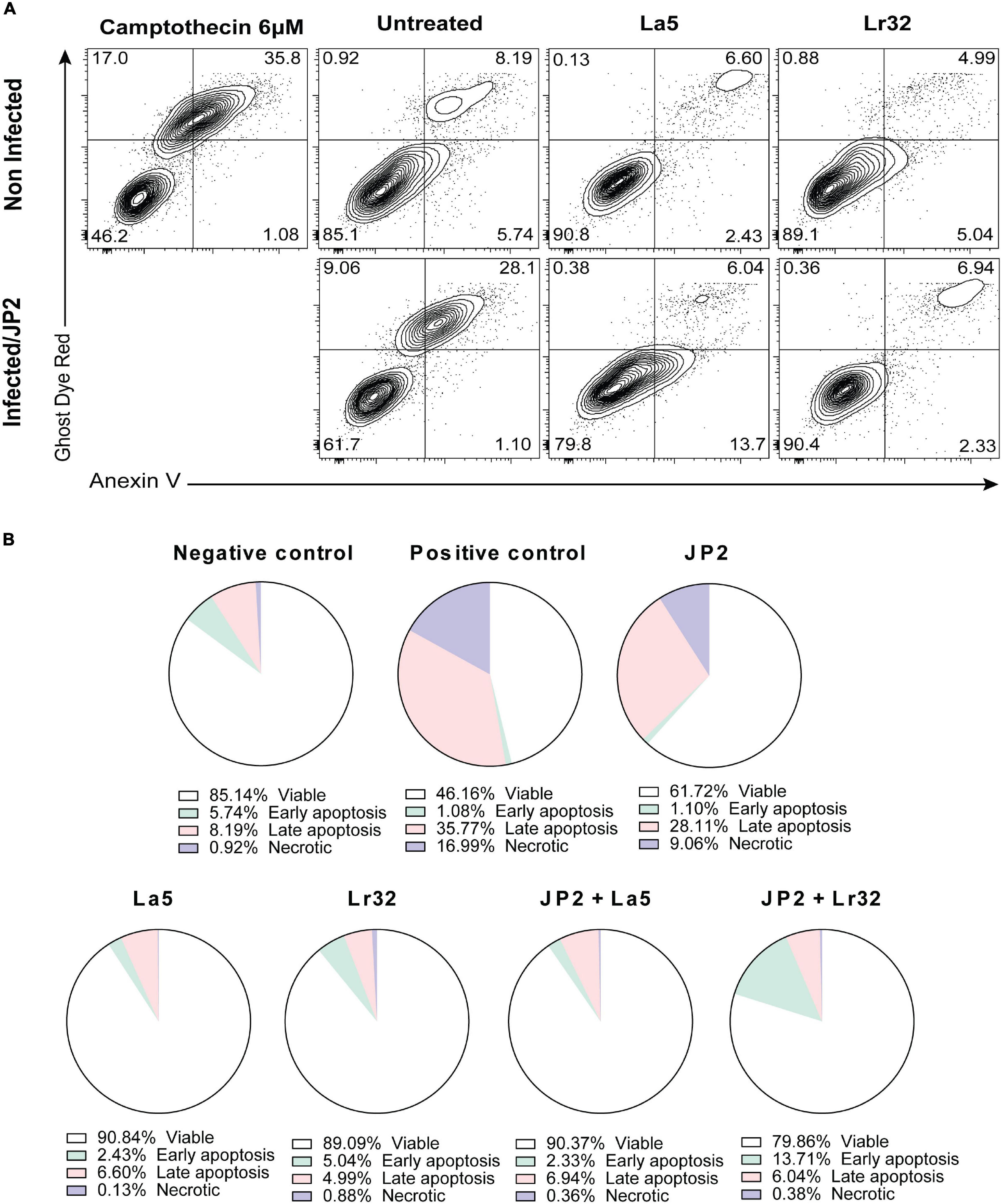

Apoptosis

The experiment was carried out with Annexin V as described by the manufacturer (FITC Annexin V apoptosis detection kit, BD Pharmingen, United States). After incubation of OBA-9 cells with A. actinomycetemcomitans and/or lactobacilli for 24 h, the plates were centrifuged, the supernatant was removed, and 500 μL of binding buffer with FITC and Ghost Dye Red (Tonbo Biosciences, San Diego, CA, United States) was added and then incubated for 20 min at room temperature away from light. Then, the plates were centrifuged, the supernatant was removed, 500 μL of binding buffer was added to the wells, and the cells were detached using a cell scraper (Kasvi, São José dos Pinhais, PR, Brazil). The cells were analyzed by a cytometry system (BD FACSCanto Flow Cytometry Systems, Piscataway, NJ. United States). As a positive control, camptothecin (6 μM) was added to the wells 6 h before the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least two independent experiments. A one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was applied for statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (BioStat Software 5.3, Belém, Brazil).

Results

Pathogen and Lactobacilli Alter Cell Viability After 24 h of Incubation

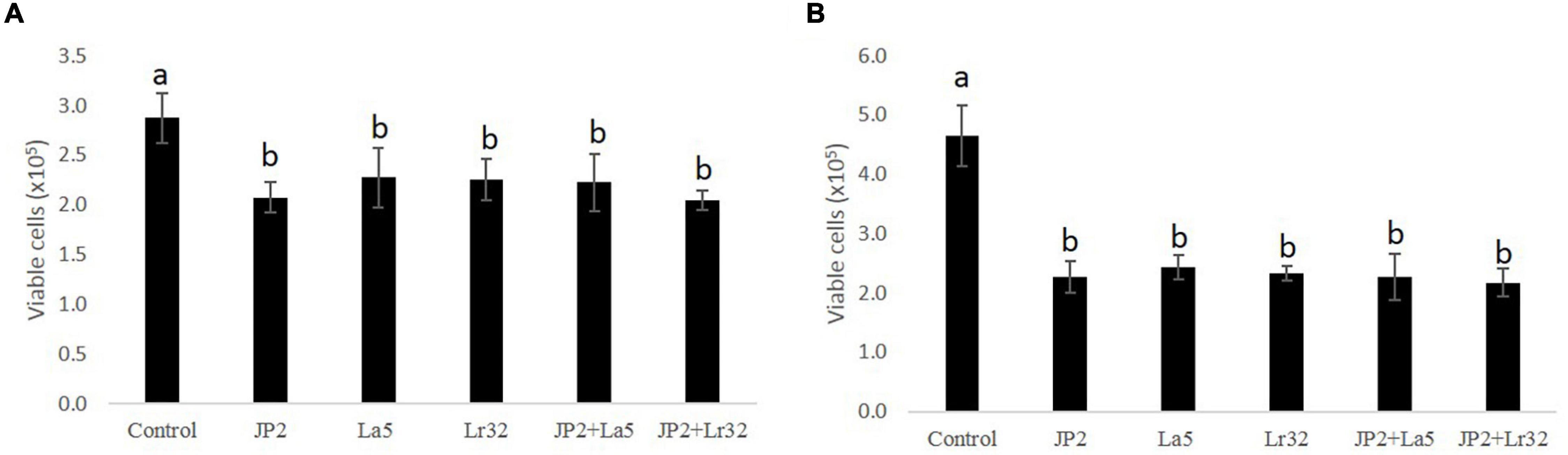

The cell viability data of OBA-9 cells after interaction with A. actinomycetemcomitans and/or probiotics after 2 and 24 h are shown in Figures 1A,B reduction in cell viability was observed for all experimental groups at 2 and 24 h compared with the uninfected control cells (p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Cell viability determined by trypan blue exclusion in OBA-9 cells mono-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans (JP2) and/or L. acidophilus La5 (La5) or L. rhamnosus Lr32 (L32) for 2 h (A) and 24 h (B). Statistical test: ANOVA/Tukey, different letters mean p < 0.05. In the y-axis is the number of viable OBA-9 cells (x105). Control corresponds to non-infected GECs.

Lactobacilli Reduced Adhesion of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans to Gingival Epithelial Cells

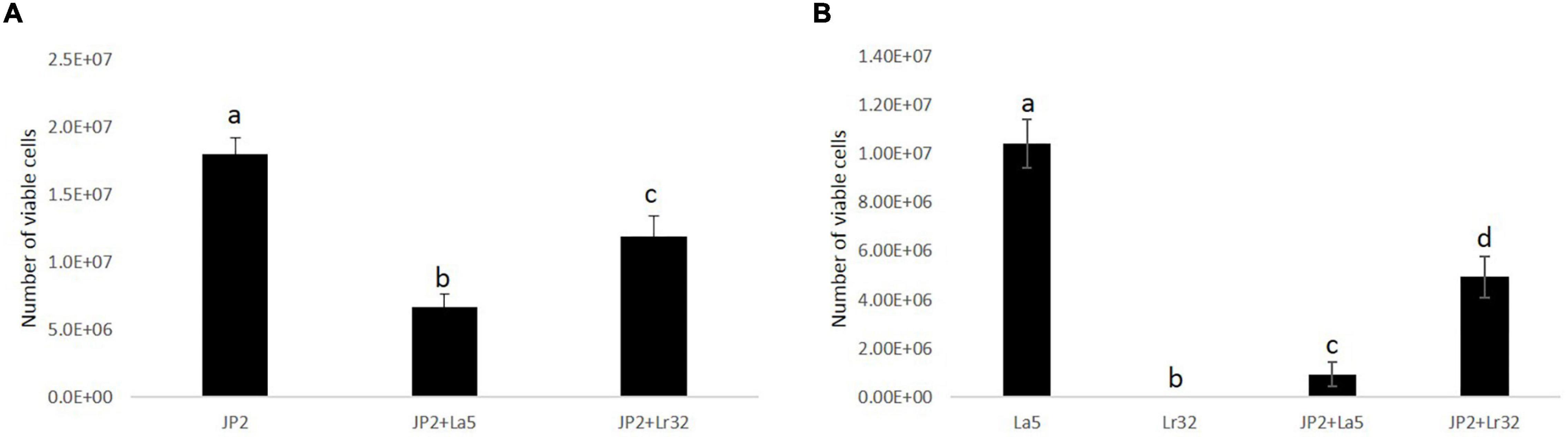

The quantitative analysis data indicated that A. actinomycetemcomitans and L. acidophilus La5 adhered/invaded OBA-9 cells, while mono-infection of OBA-9 cells with L. rhamnosus Lr32 yielded no detectable adherent lactobacilli. Both lactobacilli significantly reduced A. actinomycetemcomitans adhesion/invasion to OBA-9 cells (p < 0.05). Co-infection of OBA-9 cells with A. actinomycetemcomitans and L. acidophilus La5 yielded lower levels of the probiotic than the mono-infection. However, the co-infection of GECs with A. actinomycetemcomitans and L. rhamnosus Lr32 favored the adhesion of the lactobacilli (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A. actinomycetemcomitans (JP2) (A) and lactobacilli (B) adherent/internalized into OBA-9 mono-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans (JP2), L. acidophilus La5 (La5), or L. rhamnosus Lr32 (L32) and co-infected with the pathogen and L. acidophilus La5 (JP2 + La5) or L. rhamnosus Lr32 (JP2 + L32) for 2 h. Data are expressed as the number of bacterial cells/well, as estimated by qPCR. ANOVA/Tukey, and different letters indicate statistical differences among groups (p < 0.05).

Lactobacilli Altered Inflammatory Mediators’ Profile of Gingival Epithelial Cells Challenged With Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

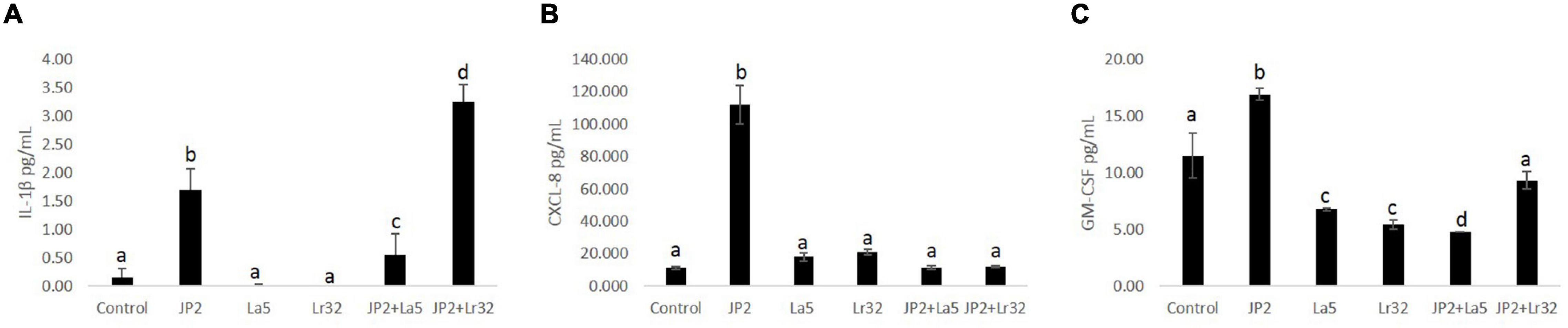

Levels of IL-1β, IL-10, CXCL-8, and GM-CSF were determined in the co-culture supernatant. No detectable levels of any studied mediator were observed in the supernatant after 2 h of co-culture with either tested bacteria, and IL-10 was not detected even after 24-h incubation (data not shown). None of the lactobacilli induced significant levels of any studied mediator. A. actinomycetemcomitans promoted a slight release of IL-1β after 24 h of interaction, which was attenuated by the co-infection with L. acidophilus La5, but increased with L. rhamnosus Lr32 (p < 0.05). CXCL-8 production was highly induced by the pathogen, and both probiotics attenuated its production (p < 0.05). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans also induced the release of GM-CSF by OBA-9 cells, which was reduced by the lactobacilli, especially by L. acidophilus La5 (p < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Levels of IL-1β (A), CXCL-8 (B), and GM-CSF (C) (pg/mL) determined by ELISA in cells supernatants of OBA-9 mono-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans (JP2) and/or L. acidophilus La5 (La5) or L. rhamnosus Lr32 (L32) after 24 h of incubation. Control corresponds to non-infected GECs. ANOVA/Tukey; different letters indicate statistical differences among groups (p < 0.05).

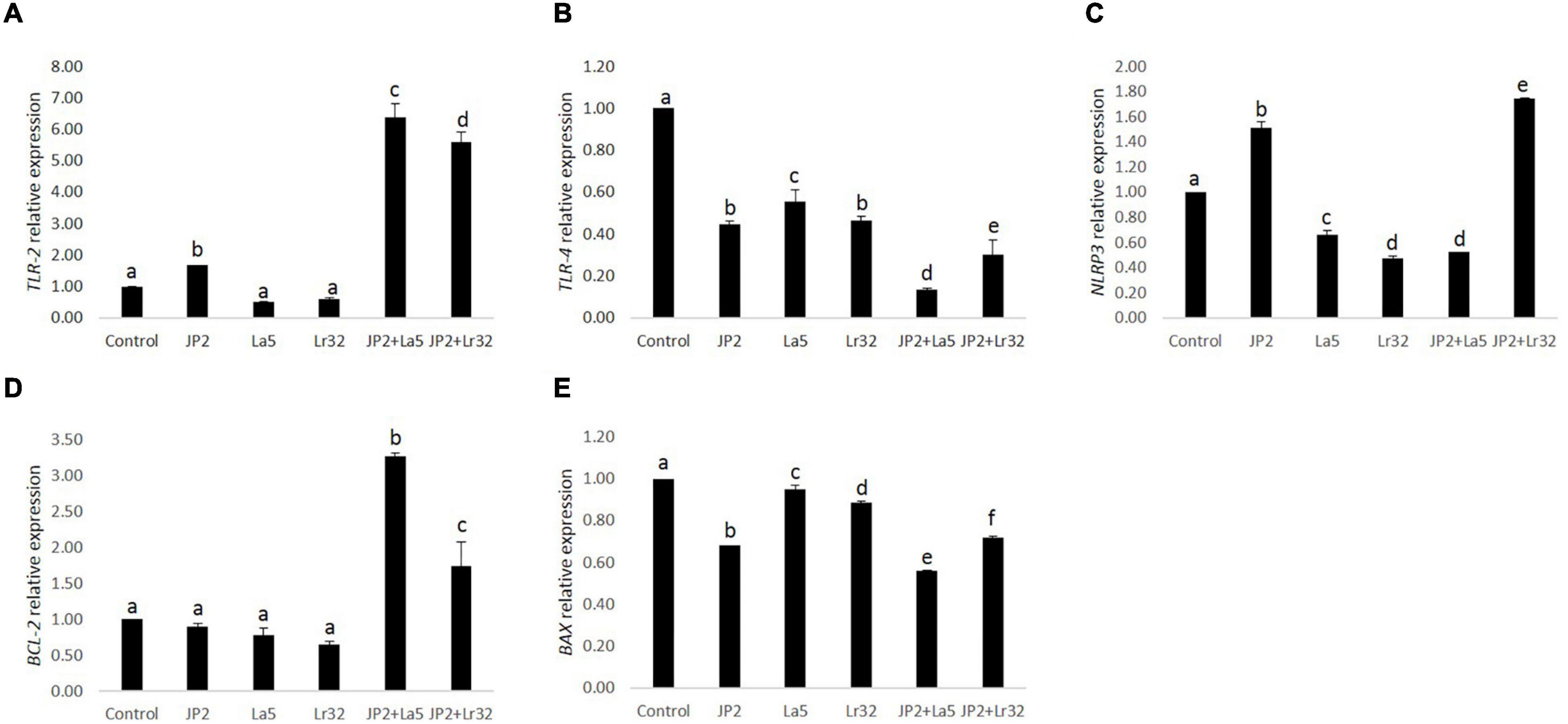

Lactobacilli Modulate the Transcription of TLR2, NLRP3, and BCL-2

The challenge of GECs with A. actinomycetemcomitans was found to upregulate TLR-2 mRNA levels, which were magnified when A. actinomycetemcomitans-infected cells were co-infected with any of the studied lactobacilli (p < 0.05). Nevertheless, TLR-4 was downregulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans, and the probiotics further reduced TLR-4 mRNA levels. Transcription of the NLRP3 was positively regulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans and negatively regulated by L. acidophilus La5. However, L. rhamnosus Lr32 further increased the expression of NLRP3. In addition, the mRNA levels of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL-2 were positively regulated when pathogen-infected epithelial cells were co-cultured with the probiotics when compared to uninfected cells (control) or to cells challenged by A. actinomycetemcomitans (p < 0.05). Moreover, the transcription of BAX, encoding a pro-apoptotic factor, was negatively regulated when epithelial cells were challenged with A. actinomycetemcomitans and probiotics when compared to uninfected cells (control) (p < 0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Relative transcription of TLR-2 (A), TLR-4 (B), NLRP3 (C), BCL-2 (D), and BAX (E) in GECs mono-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans (JP2) and/or L. acidophilus La5 (La5) or L. rhamnosus Lr32 (Lr32) for 24 h. Data on target genes were normalized to mRNA levels of the GAPDH reference gene (internal control). Control corresponds to non-infected GECs. ANOVA/Tukey, and different letters indicate statistical differences among groups (p < 0.05).

Apoptosis

Infection with A. actinomycetemcomitans significantly increased the number of apoptotic cells (Annexin V positive, Ghost Dye Red negative) after 24 h of interaction compared with the negative control (p < 0.05). Furthermore, none of the lactobacilli alone interfered with cell viability compared to the negative control. Nevertheless, in the co-culture of A. actinomycetemcomitans with any of the lactobacilli, a significant decrease in apoptotic and necrotic cells (p < 0.05) was observed.

Discussion

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans initiates an aberrant inflammatory response in the gingival periodontal tissues through the interaction of its virulence factors with host cells (Fives-Taylor et al., 1999). The first cells that subgingival organisms face are the gingival epithelium, which acts as a physical barrier and plays an important role in innate immune response (Groeger and Meyle, 2019).

Using a co-culture model, our data showed that A. actinomycetemcomitans adhesion to GECs was reduced by both tested lactobacilli, although the inhibition of the adhesion promoted by strain L. acidophilus La5 was more pronounced than that by L. rhamnosus Lr32. Furthermore, L. acidophilus La5 was able to adhere to GECs, and this adhesion was reduced by the pathogen, suggesting that this probiotic could adhere to the oral epithelium surface and compete with the pathogen for adhesion sites. Alternatively, other competitive exclusion mechanisms, such as the production of acids, bacteriocins, or oxidative compounds, also may be involved (Cáceres et al., 2011; Teughels et al., 2011). On the other hand, L. rhamnosus Lr32 only yielded detected levels of adherent bacteria in GECs co-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans, suggesting that the pathogen bound to GECs could act as a bridge, aggregating with L. rhamnosus.

The antimicrobial activity of lactobacilli has been reported. Previous data reported that lactobacilli suppressed in vitro growth of periodontal pathogens in a strain- and a species-specific way (Koll-Klais et al., 2005). Similarly, in vitro data demonstrated that lactobacilli reduced the interaction of P. gingivalis to epithelial cells (Albuquerque-Souza et al., 2018) and reduced P. gingivalis biofilm formation but did not affect commensal streptococci (Ishikawa et al., 2020).

Our group has also shown that secreted products of L. acidophilus La5 were able to reduce biofilm formation by A. actinomycetemcomitans and pre-formed biofilm, whereas transcription of cytolethal distending toxin (cdtB) and leukotoxin (ltxA) was downregulated by cell-free pH-neutralized supernatants of L. acidophilus La5 and L. rhamnosus Lr32 (Ishikawa et al., 2021). The levels of ltxA and cdtB were also analyzed in another study, and both genes were downregulated in a time-dependent way when A. actinomycetemcomitans was cultured with Lactobacillus salivarius and Lactobacillus gasseri cell-free supernatants (Nissen et al., 2014).

Cell response to microbial challenges is mediated by the recognition of bacterial pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) by pattern recognition receptors (PPRs), located in the cell membrane and in the cytosol. Cell membrane receptors, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), represent one of the first mechanisms of immune defense against invading organisms (Groeger and Meyle, 2019). A major consequence of the activation of surface TLRs, such as TLR-2 and TLR-4, is the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which play an essential role in innate and adaptive immune responses (Beklen et al., 2008; Oliveira-Nascimento et al., 2012; Groeger and Meyle, 2019).

In this study, the expression of TLR-2 and TLR-4 was evaluated in cells challenged with A. actinomycetemcomitans and with the probiotics. Our data indicated that A. actinomycetemcomitans challenged and/or the probiotics downregulated TLR-4 expression, and this reduction was more pronounced when the cells were co-infected with L. acidophilus La5. On the other hand, A. actinomycetemcomitans challenge promoted a slight upregulation of TLR-2, whereas mono-infection with probiotics did not alter baseline TLR-2 mRNA levels. However, the combination of the challenge with the pathogen and the probiotics led to a statistically significant increase in TLR-2 expression.

TLR-2 is highly expressed in the basal layer of the gingival epithelium, whereas its levels are lower in the superficial layers that are more exposed to microorganisms (Groeger and Meyle, 2019). It is well known that lipoproteins and teichoic acid on the cell surface of lactobacilli are recognized by TLR-2 (Sengupta et al., 2013). In addition, certain lactobacilli such as L. plantarum BFE 1685 and L. rhamnosus GG can lead to TLR-2, but not to TLR4, upregulation in intestinal epithelial cells, but this effect is reduced when the cells were challenged with an enteropathogen (Vizoso et al., 2009). It has been shown that the probiotic anti-inflammatory effects are dependent on TLR-2 recognition (Sun et al., 2017). Thus, the enhancement in TLR2 expression promoted by lactobacilli in GECs would lead to a decrease in the production of inflammatory mediators in cells challenged by the pathogen.

Indeed, the co-infection of A. actinomycetemcomitans-challenged cells with the probiotics resulted in reduced levels of certain studied factors. The interaction of A. actinomycetemcomitans with GECs resulted in the activation of epithelial cells, which produced CXCL-8 and GM-CSF, as previously shown (Uchida et al., 2001; Stathopoulou et al., 2010; Umeda et al., 2012), whereas exposure to the probiotics attenuated the response of GECs, which produced lower levels of CXCL-8 and GM-CSF. This altered response cannot be regarded only as the reduced interaction of GECs with the pathogen, since both probiotics reduced adherence of A. actinomycetemcomitans to GECs but acted differently in altering the cell response. L. acidophilus La5 modulated the inflammatory response against the challenge with A. actinomycetemcomitans by decreasing the release of CXCL-8, GM-CSF, and IL-1β, whereas L. rhamnosus Lr32 reduced the levels of CXCL-8 and GM-CSF but increased the production of IL-1β.

We have shown that A. actinomycetemcomitans per se can induce IL-1β production, as seen in cell supernatant of GECs (Figure 3). The secretion of active IL-1β requires cytosolic sensing by intracellular receptors, including NLRP3 (Figure 4), which leads to the formation of multiprotein cytoplasmic complexes, called inflammasomes. These complexes activate caspase-1, which results in the release of mature IL-1β (Franchi et al., 2012). Previous data indicated that A. actinomycetemcomitans can activate the inflammasome in leukocytes and macrophages, particularly due to the production of the cytolethal distending toxin (Belibasakis and Johansson, 2012; Ando-Suguimoto et al., 2014; Shenker et al., 2015). On the other hand, the response to A. actinomycetemcomitans challenge for 8 h on primary gingival epithelial cells did not indicate inflammasome activation (Ando-Suguimoto et al., 2020), although there are no data on longer incubation periods.

Probiotics may attenuate the secretion of IL-1β, as our data indicated when L. acidophilus La5 was tested when combined with A. actinomycetemcomitans challenge in GECs. However, the addition of L. rhamnosus Lr32 to GECs challenged with the pathogen resulted in increased production of IL-1β. The increased IL-1β levels in cells co-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans and L. rhamnosus Lr32 suggest that this strain may act synergistically with the pathogen to activate the inflammasome. This hypothesis is corroborated by our observation of the upregulation of NRLP3, encoding the intracellular receptor for NRLP3 inflammasome activation, when the GECs were co-cultured with A. actinomycetemcomitans and L. rhamnosus Lr32. It seems that L. rhamnosus Lr32 may not activate the inflammasome itself but may increase inflammasome activation under certain conditions. The increased production of IL-1β promoted by L. rhamnosus Lr32 in cells challenged with A. actinomycetemcomitans is similar to what was observed in the co-infection of the same probiotic with P. gingivalis on GECs (Albuquerque-Souza et al., 2018). Other strains of L. rhamnosus were also shown to activate inflammasome, which would favor pathogen elimination (Korpela et al., 2012), but may induce further damage in diseases associated with an exacerbated inflammatory response such as periodontitis (Ebersole et al., 2013).

CXCL-8 is a chemoattractant produced by several types of cells to attract neutrophils and other defense cells to the infection site (Russo et al., 2014). Despite its importance in defense, the production of CXCL-8 in already inflamed tissues, such as in periodontitis, may contribute to the loss of the connective tissue and the destruction of the alveolar bone (Finoti et al., 2017). CXCL-8 production by gingival epithelial cells is dependent on the composition of the microbial community (Belibasakis et al., 2013), and data on CXCL-8 levels in the gingival crevicular fluid of periodontitis patients are still contradictory (Finoti et al., 2017). Some probiotic lactobacilli may lead to increased (Vizoso et al., 2009) or decreased (Stamatova et al., 2010) CXCL-8 production in vitro, although clinically controlled trials of periodontal patients using probiotics as an adjunctive therapy to conventional treatment indicated decreased levels of CXCL-8 in the gingival crevicular fluid (Twetman et al., 2009).

Our data showed that both studied lactobacilli were able to decrease GM-CSF released by GECs co-cultured with A. actinomycetemcomitans. GM-CSF is an important cytokine in the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of macrophages and neutrophils (Hamilton, 2008), and it is known to be upregulated after the interaction between A. actinomycetemcomitans and gingival epithelial cells (Umeda et al., 2012), which results in the recruitment and differentiation of immune cells, such as macrophages, which are responsible for a pro-inflammatory response involving antigen presentation, phagocytosis, and release of IL-1β (Gholizadeh et al., 2017). A previous study has demonstrated that a mixture of three probiotics (Enterococcus faecalis, Bifidobacterium longum, and L. acidophilus) decreased the levels of GM-CSF produced by gastric mucosal epithelial cells infected with Helicobacter pylori (Yu et al., 2015). L. rhamnosus L34 and L. casei L39 conditioned media decreased the production of GM-CSF by Clostridium difficile-stimulated HT-29 intestinal epithelial cells, which is the main cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea and colitis (Boonma et al., 2014). Thus, the decrease in GM-CSF levels seems beneficial in inflamed mucosa surfaces, including in periodontitis. Increased GM-CSF levels were associated with an allele of increased susceptibility to aggressive periodontitis (Harris et al., 2020), whereas the destruction of the alveolar bone was dependent on GM-CSF in a mouse experimental model (Lam et al., 2015).

Since we observed a reduction in cell viability of GECs co-infected with A. actinomycetemcomitans and/or lactobacilli, we analyzed the expression of genes involved in apoptosis, of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL-2, and of the pro-apoptotic BAX. Co-culture with A. actinomycetemcomitans did not alter the transcription of BCL2 and reduced mRNA levels of BAX, whereas the probiotics altered their expression. Both lactobacilli induced the transcription of BCL2 in A. actinomycetemcomitans-challenged GECs, and L. acidophilus LA5 also decreased the transcription of BAX, suggesting that the probiotics would protect epithelial cells from apoptosis, confirmed by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 5). Other studies reported the effectiveness of probiotic lactobacilli in altering the expression of genes involved in apoptosis of hepatocytes in vitro (Sharma et al., 2011) and in vivo experimental models (Chen et al., 2018).

Figure 5. Cytotoxicity by A. actinomycetemcomitans is mediated through apoptosis in gingival epithelial cells (GECs). (A) GECs were treated with A. actinomycetemcomitans at an MOI of 1:100 for 24 h and/or L. acidophilus La5 or L. rhamnosus Lr32 at an MOI 1:10. Camptothecin 6 uM was used as the positive control. The cells were stained with Annexin V and Ghost Dye Red and then analyzed using flow cytometry. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells in each panel. (B) Pie chart with the percentage of viable, early apoptosis, late apoptosis, and necrotic cells.

In summary, this evidence suggests that lactobacilli, especially L. acidophilus La5, can modulate the inflammatory response mediated by A. actinomycetemcomitans in GECs. The evaluated probiotics strains were able to reduce pathogenic bacteria adhesion to host cells, alter the release of inflammatory chemo/cytokines in a strain-specific way, and alter the pathogen’s recognition profile and influence the production of the anti-apoptotic gene. These results illustrate that probiotic modulatory mechanisms should be evaluated toward controlling the inflammatory response followed by chronic inflammation. A more detailed understanding of their properties could result in their use as an adjunctive therapy for periodontal disease.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

MM conceptualized and designed the project, planned the assays, and wrote the manuscript. MB planned and ran the assays and helped to wrote the manuscript. DK, EA-S, NS, GA-S, and KI helped with the sample analyses. All authors revised the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) grant #2015/18273-9. NS, MB, DK, EA-S, and KI were supported by scholarships from FAPESP 2017/22345-0, 2017/16377-7, 2016/13159-6, 2016/14687-6, and 2016/13156-7. EA-S was also supported by CAPES.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The OBA-9 cells used in this study were gently given by Shinya Murakami (Osaka University, Japan). We thank the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for supporting this study and for the scholarships of NS, MB, DK, EA-S, and KI. We also thank Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for the scholarship of EA-S.

Footnotes

References

Albuquerque-Souza, E., Ishikawa, K. H., Mayer, M. P. A., Simionato, M. R. L., Ando-suguimoto, E., Balzarini, D., et al. (2018). Probiotics alter the immune response of gingival epithelial cells challenged by porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Periodontal Res. 54, 115–127. doi: 10.1111/jre.12608

Amado, P. P. P., Kawamoto, D., Albuquerque-Souza, E., Franco, D. C., Saraiva, L., Casarin, R. C. V., et al. (2020). Oral and fecal microbiome in molar-incisor pattern periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10:583761. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.583761

American Academy of Periodontology [AAP] (2001). Glossary of Periodontal Terms, 4th Edn. Chicago, Ill: AAP.

Anders, D., and Haubek, J. (2014). - Pathogenicity of the highly leukotoxic JP2 clone of aggregatibacter. J. Oral. Microbiol. 6:23980. doi: 10.3402/jom.v6.23980

Ando-Suguimoto, E. S., Benakanakere, M. R., Mayer, M. P. A., and Kinane, D. F. (2020). Distinct signaling pathways between human macrophages and primary gingival epithelial cells by aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Pathogens 9:248. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9040248

Ando-Suguimoto, E. S., Silva, M. P., Kawamoto, D., Chen, C., DiRienzo, J. M., and Mayer, M. P. A. (2014). The cytolethal distending toxin of aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans inhibits macrophage phagocytosis and subverts cytokine production. Cytokine 66, 46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.12.014

Aroniadis, O. C., and Brandt, L. J. (2014). Intestinal microbiota and the efficacy Gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 230–237.

Beklen, A., Hukkanen, M., Richardson, R., and Konttinen, Y. T. (2008). Immunohistochemical localization of toll-like receptors 1-10 in periodontitis. Oral. Microbiol. Immunol. 23, 425–431.

Belibasakis, G. N., and Johansson, A. (2012). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans targets NLRP3 and NLRP6 inflammasome expression in human mononuclear leukocytes. Cytokine 59, 124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.03.016

Belibasakis, G. N., Thurnheer, T., and Bostanci, N. (2013). Interleukin-8 responses of multi-layer gingival epithelia to subgingival biofilms: role of the ‘Red Complex’. species. PLoS One 8:e81581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081581

Boonma, P., Spinler, J. K., Venable, S. F., Versalovic, J., and Tumwasorn, S. (2014). Lactobacillus rhamnosus L34 and Lactobacillus casei L39 suppress clostridium difficile-induced IL-8 production by colonic epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 14:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-177

Bueno, L. C., Mayer, M. P., and DiRienzo, J. M. (1998). Relationship between conversion of localized juvenile periodontitis-susceptible children from health to disease and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin promoter structure. J. Periodontol. 69, 998–1007. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.9.998

Cáceres, M., Romero, A., Copaja, M., Díaz-Araya, G., Martínez, J., and Smith, P. C. (2011). Simvastatin alters fibroblastic cell responses involved in tissue repair. J. Periodontal. Res. 46, 456–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01360.x

Chen, X., Zhang, J., Yi, R., Mu, J., and Xin, Z. (2018). Hepatoprotective effects of lactobacillus on carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:2212. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082212

de Vrese, M., Winkler, P., Rautenberg, P., Harder, T., Noah, C., Laue, C., et al. (2006). Probiotic bacteria reduced duration and severity but not the incidence of common cold episodes in a double blind, randomized, controlled trial. Vaccine 24, 6670–6674. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.048

Ebersole, J. L., Dawson, D. R., Morford, L. A., Peyyala, R., Craig, S., and Gonzaléz, O. A. (2013). Periodontal disease immunology: ‘double indemnity’ in protecting the host. Periodontology 62, 163–202. doi: 10.1111/prd.12005

FAO/WHO (2002). Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food London. London: Ontario, ON.

Finoti, L. S., Nepomuceno, R., Pigossi, S. C., Corbi, S. C., Secolin, R., and Scarel-Caminaga, R. M. (2017). Association between Interleukin-8 levels and chronic Periodontal disease: a PRISMA-Compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 96:e6932. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006932

Fives-Taylor, P. M., Meyer, D. H., Mintz, K. P., and Brissette, C. (1999). Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Periodontology 20, 136–167.

Franchi, L., Muñoz-Planillo, R., and Núñez, G. (2012). Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat. Immunol. 13, 325–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2231

Gholizadeh, P., Pormohammad, A., Eslami, H., Shokouhi, B., Fakhrzadeh, V., and Kafil, H. S. (2017). Oral pathogenesis of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Microb. Pathog. 113, 303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.11.001

Groeger, S., and Meyle, J. (2019). Oral mucosal epithelial cells. Front. Immunol. 10:208. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00208

Hajishengallis, G., and Lamont, R. J. (2012). Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the Polymicrobial Synergy and Dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 27, 409–419.

Hamilton, J. A. (2008). Colony-Stimulating factors in inflammation and autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 533–544. doi: 10.1038/nri2356

Harris, T. H., Wallace, M. R., Huang, H., Li, H., Mohiuddeen, A., Gong, Y., et al. (2020). Association of P2RX7 functional variants with localized aggressive periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 55, 32–40. doi: 10.1111/jre.12682

Haubek, D., Ennibi, O. K., Poulsen, K., Benzarti, N., and Baelum, V. (2004). The highly leukotoxic JP2 clone of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and progression of periodontal attachment loss. J. Dent. Res. 83, 767–770. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301006

Ishikawa, K. H., Bueno, M. R., Kawamoto, D., Simionato, M. R. L., and Mayer, M. P. A. (2021). Lactobacilli postbiotics reduce biofilm formation and alter transcription of virulence genes of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 36, 92–102. doi: 10.1111/omi.12330

Ishikawa, K. H., Mita, D., Kawamoto, D., Nicoli, J. R., Albuquerque-Souza, E., Simionato, M. R. L., et al. (2020). Probiotics alter biofilm formation and the transcription of porphyromonas gingivalis virulence-associated genes. J. Oral Microbiol. 12:1805553. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2020.1805553

Kajiya, M., Komatsuzawa, H., Papantonakis, A., Seki, M., Makihira, S., Ouhara, K., et al. (2011). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans Omp29 is associated with bacterial entry to gingival epithelial cells by F-Actin rearrangement. PLoS One 6:e18287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018287

Koll-Klais, P., Mandar, R., Leibur, E., Hammarstrom, L., Marcotte, H., and Mikelsaar, M. (2005). Oral lactobacilli in chronic periodontitis and periodontal health: species composition and antimicrobial activity. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 20, 354–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.2005.00239.x

Korpela, R., Julkunen, I., Kekkonen, R. A., Miettinen, M., Kankainen, M., Pietilä, T. E., et al. (2012). Nonpathogenic Lactobacillus rhamnosus activates the inflammasome and antiviral responses in human macrophages. Gut Microbes 3, 510–522. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21736

Lam, R. S., O’Brien-Simpson, N. M., Hamilton, J. A., Lenzo, J. C., Holden, J. A., and Brammar, G. C. (2015). GM-CSF and UPA are required for Porphyromonas gingivalis -induced alveolar bone loss in a mouse periodontitis model. Immunol. Cell Biol. 93, 705–715. doi: 10.1038/icb.2015.25

Lamell, C. W., Griffen, A. L., McClellan, D. L., and Leys, E. J. (2000). Acquisition and colonization stability of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 1196–1199. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.3.1196-1199.2000

Lamont, R. J., and Hajishengallis, G. (2015). Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis in Inflammatory disease. Trends Mol. Med. 21, 172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.004

Mao, X., Gu, C., Hu, H., Tang, J., and Chen, D. (2016). Dietary Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supplementation improves the mucosal barrier function in the intestine of weaned piglets challenged by porcine rotavirus. PLoS One 11:e0146312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146312

Matsubara, V. H., Bandara, H. M. H. N., Ishikawa, K. H., Mayer, M. P. A., and Samaranayake, L. P. (2016). The role of probiotic bacteria in managing periodontal disease: a systematic review. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Therapy 14, 643–655. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2016.1194198

Matsubara, V. H., Ishikawa, K. H., Ando-Suguimoto, E. S., Bueno-Silva, B., Nakamae, A. E. M., and Mayer, M. P. A. (2017). Probiotic bacteria alter pattern-recognition receptor expression and cytokine profile in a human macrophage model challenged with candida albicans and lipopolysaccharide. Front. Microbiol. 8:2280. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02280

Mayer, M. P. A., Bueno, L. C., Hansen, E. J., and DiRienzo, J. M. (1999). Identification of a cytolethal distending toxin gene locus and features of a virulence-associated region in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 67, 1227–1237.

Nissen, L., Sgorbati, B., Biavati, B., and Belibasakis, G. N. (2014). Lactobacillus salivarius and L. gasseri down-Regulate Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans exotoxins expression. Ann. Microbiol. 64, 611–617. doi: 10.1007/s13213-013-0694-x

Oliveira-Nascimento, L., Massari, P., and Wetzler, L. M. (2012). The role of TLR2 In infection and Immunity. Front. Immunol. 3:79. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00079

Pfaffl, M. W. (2001). A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT - PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 16–21.

Raff, A., and Hunt, L. C. (2012). Probiotics for periodontal health: a review of the literature. J. Dental Hygiene: JDH 86, 71–81.

Roberts, F. A., and Darveau, R. P. (2002). Beneficial bacteria of the periodontium. Periodontology 2000, 40–50.

Rudney, J. D., Chen, R., and Pan, Y. (2003). Endpoint quantitative PCR assays for Bacteroides forsythus, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Periodontal Res. 38, 465–470. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.00670.x

Russo, R. C., Garcia, C. C., Teixeira, M. M., and Amaral, F. A. (2014). The CXCL8/IL-8 chemokine family and its receptors in inflammatory diseases. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 10, 593–619. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.894886

Sengupta, R., Altermann, E., Anderson, R. C., McNabb, W. C., Moughan, P. J., and Roy, N. C. (2013). The role of cell surface architecture of Lactobacilli in host-microbe interactions in the gastrointestinal tract. Med. Inflamm. 2013:237921. doi: 10.1155/2013/237921

Sharma, S., Singh, R. L., and Kakkar, P. (2011). Modulation of Bax/Bcl-2 and caspases by probiotics during acetaminophen induced apoptosis in primary hepatocytes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 49, 770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.11.041

Shenker, B. J., Boesze-Battaglia, K., Scuron, M. D., Walker, L. P., Zekavat, A., and Dlakić, M. (2016). The toxicity of the Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans cytolethal distending toxin correlates with its phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate phosphatase activity. Cell Microbiol. 18, 223–243. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12497

Shenker, B. J., Ojcius, D. M., Walker, L. P., Zekavat, A., Scuron, M. D., and Boesze-Battaglia, K. (2015). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans cytolethal distending toxin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages, leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines. Infect. Immun. 83, 1487–1496. doi: 10.1128/IAI.03132-3114

Stamatova, I., Kari, K., and Meurman, J. H. (2010). Probiotic challenge of oral epithelial cells in vitro. Int. J. Probiotics Prebiotics 5, 13–19.

Stathopoulou, P. G., Benakanakere, M. R., Galicia, J. C., and Kinane, D. F. (2010). Epithelial cell pro-inflammatory cytokine response differs across dental plaque bacterial species. J. Clin. Periodontol. 37, 24–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01505.x

Sun, K., Xu, D., Xie, C., Plummer, S., Tang, J., Yang, X. F., et al. (2017). Lactobacillus paracasei modulates LPS-Induced inflammatory cytokine release by monocyte-macrophages via the up-regulation of negative regulators of NF-KappaB signaling in a TLR2-Dependent manner. Cytokine 92, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.01.003

Teughels, W., Loozen, G., and Quirynen, M. (2011). Do probiotics offer opportunities to manipulate the periodontal oral microbiota? J. Clin. Periodontol. 38, (Suppl. 11), 159–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01665.x

Tonetti, M. S., Greenwell, H., and Kornman, K. S. (2018). Staging and grading of periodontitis: framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J. Periodontol. 45, 149–161. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12945

Tsai, C. C., Shenker, B. J., DiRienzo, J. M., Malamud, D., and Taichman, N. S. (1984). Extraction and isolation of a leukotoxin from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans with polymyxin B. Infect Immun. 43, 700–705. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.700-705.1984

Twetman, S., Derawi, B., Keller, M., Ekstrand, K., Yucel-Lindberg, T., and Stecksen-Blicks, C. (2009). Short-Term effect of chewing gums containing probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri on the levels of inflammatory mediators in gingival crevicular fluid. Acta Odontol. Scand. 67, 19–24. doi: 10.1080/00016350802516170

Uchida, Y., Shiba, H., Komatsuzawa, H., Takemoto, T., Sakata, M., Fujita, T., et al. (2001). Expression of IL-1 Beta and IL-8 by human gingival epithelial cells in response to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Cytokine 14, 152–161. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0863

Umeda, J. E., Demuth, D. R., Ando-Suguimoto, E. S., Faveri, M., and Mayer, M. P. A. (2012). Signaling transduction analysis in gingival epithelial cells after infection with Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 27, 23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2011.00629.x

Vizoso, P., María, G., Gómez, M. R., Seifert, S., Watzl, B., Holzapfel, W. H., et al. (2009). Lactobacilli stimulate the innate immune response and modulate the TLR expression of HT29 intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 133, 86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.05.013

Wang, G. P. (2015). Defining functional signatures of dysbiosis in periodontitis progression. Genome Med. 7:40. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0165-z

Keywords: gingival epithelial cells, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, probiotics, periodontitis, immune response

Citation: Bueno MR, Ishikawa KH, Almeida-Santos G, Ando-Suguimoto ES, Shimabukuro N, Kawamoto D and Mayer MPA (2022) Lactobacilli Attenuate the Effect of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans Infection in Gingival Epithelial Cells. Front. Microbiol. 13:846192. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.846192

Received: 30 December 2021; Accepted: 29 March 2022;

Published: 04 May 2022.

Edited by:

Jennifer Angeline Gaddy, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Alejandra Ochoa-Zarzosa, Michoacana University of San Nicolás de Hidalgo, MexicoKoshy Philip, University of Malaya, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Bueno, Ishikawa, Almeida-Santos, Ando-Suguimoto, Shimabukuro, Kawamoto and Mayer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcia P. A. Mayer, mpamayer@icb.usp.br

Manuela R. Bueno

Manuela R. Bueno Karin H. Ishikawa

Karin H. Ishikawa Gislane Almeida-Santos3

Gislane Almeida-Santos3 Ellen S. Ando-Suguimoto

Ellen S. Ando-Suguimoto Natali Shimabukuro

Natali Shimabukuro Marcia P. A. Mayer

Marcia P. A. Mayer