“Everything will be all right (?)”: Discourses on COVID-19 in the Italian linguistic landscape

- Department of Humanities, University for Foreigners of Siena, Siena, Italy

The study of the linguistic landscape (LL) focuses on the representations of languages on signs placed in the public space and on the ways in which individuals interact with these elements. Regulatory, infrastructural, commercial, and transgressive discourses, among others, emerge in these spaces, overlapping, complementing, or opposing each other, reflecting changes taking place and, in turn, influencing them. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all aspects of life, including cities, neighborhoods, and spaces in general. Against this background, the study of the LL is fundamental not only to better understand the ways in which places have changed and how people are interpreting and experiencing them but also to analyze the evolution of COVID-19 discourses since the pandemic broke out. This contribution aims to investigate how and in what terms the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on the Italian LL, considered both in its entirety, as a single body that, regardless of local specificities, responded to and jointly reflected on the shared shock, and specifically, assuming the city of Florence as a case study. The data collected in the three main phases of the pandemic include photographs of virtual and urban LL signs and interviews, which were analyzed through qualitative content analysis with the aim of exploring citizens' perceptions and awareness of changes in the LL of their city. The results obtained offer a photograph of complex landscapes and ecologies, which are multimodal, multi-layered, and interactive, with public and private discourses that are strongly intertwined and often complementary. Furthermore, the diachronic analysis made it possible to identify, on the one hand, points in common with the communication strategies in the different phases, both at a commercial and regulatory level. On the other hand, strong differences emerged in the bottom-up representations, characterized in the first phase by discourses of resilience, tolerance, hope, solidarity, and patriotism, and in the second and third phases by disillusionment, despair, and protest.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a disruption in sociolinguistic research models, as regards the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, including data collected through the linguistic landscape approach (henceforth, LL). The processes of internationalization, urban conformation, and their management have had to deal with the dynamics linked to the mobility of people, dynamics which have radically changed in the 2-year period of 2020–2021. There is no sector of linguistic research (and not only) that is not considering the effects that the pandemic has had on verbal and non-verbal interactions, on attitudes and perceptions, and on the management of the communicative space and the discourses that can, or cannot, also appear visually in the streets of the cities (Adami et al., 2020).

It is at this juncture that this contribution is inserted, as it aims to provide a synthesis of extensive research, started in the spring of 2020 and completed at the beginning of 2022. The general purpose of the study is to verify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Italian LL and, in particular, on the Florentine LL (cf. Bagna et al., forthcoming). It was decided to take the city of Florence as a case study as the administrative center of the Tuscany region has been subject for years to touristification processes (Gotham, 2005), i.e., the transformation of both residential and commercial spaces into tourist destinations or places of consumption. According to the data processed by the Florence Tourist Studies Center, in fact, in 2018, the general flows reached 5.3 million arrivals and just under 15.5 million presences. These massive flows have led to the transformation of several neighborhoods of the city, especially in the historic center.

This research is highly interdisciplinary, multisensory, and multi-temporal, as it is not limited to a synchronic analysis of the visual data displayed in urban LLs. Moreover, it explores the variation in diachronic terms, while expanding the LL approach to the so-called cyberscapes (Ivkovic and Lotherington, 2009) and soundscapes (Scarvaglieri et al., 2013).

Since the scope of this research is extensive and multifaceted, the discussion will be limited to some of the results obtained, reconstructing the stages of the pandemic in Italy through a qualitative analysis of the data collected, which consist of signs in the urban and virtual LL, interviews, and observations (cf. Section 3). Central to this perspective is the integrated analysis of top-down and bottom-up discourses (and signs), explored as different sides of the same coin. To understand how perceptions and representations of the pandemic have changed over time, in fact, it seems essential to consider both institutional and private actors and sign makers, their discourses, and how the latter intersect with each other. Accordingly, the research questions to be answered here are:

• What discourses on COVID-19 materialized in the Italian LL in the different phases of the pandemic?

• Which actors and how did they convey these discourses?

• What was the perception and awareness of citizens at the emergence of these discourses?

The need to consider the temporal component is linked to the fact that the evolution of the pandemic has involved the adoption of different measures and rules, as well as heterogeneous reactions on the part of the population. Initially, it was assumed that these issues would have been reflected precisely in the LL, carnival mirror (Gorter, 2012, p. 11) of the roles played by languages and ideologies in society.

In Italy, the first wave of the pandemic officially began on 20 February 2020, when the first Italian case of a patient suffering from COVID-19 was discovered. From that moment on, there was a rapid succession of decrees and regulations, with which increasingly restrictive measures were introduced to control the spread of the pandemic, which resulted in a national lockdown from 9 March 2020. Until the beginning of May 2020, schools and universities were closed, moving to teach online, shops deemed non-essential were closed, and gatherings were banned.

The arrival of the summer of 2020 gave a false feeling of normality and freedom, which clashed with an increase in infections and the consequent restrictive measures starting from September 2020, when Italy entered the second wave of COVID-19. In October 2020, a new system was, therefore, introduced, through which the Italian regions were distinguished by color, from white to red, passing through yellow and orange. Each color included increasingly restrictive measures. Only from the end of April 2021, due to the results of the measures themselves and the vaccination campaign, people were able to start moving around and repopulating the city streets.

In all these months, the LL evolved rapidly: the overview that will emerge from this study aims to offer an unprecedented reconstruction of what has been experienced and conveyed in the Italian LL in the past 2 years, opening to further and heterogeneous perspectives of analyses.

2. Immune cities: Discourses about COVID-19 pandemic in the linguistic landscape

The need to investigate the changes taking place in the LL arises from the awareness of how the “linguistic landscape, with its longstanding focus on the role of language and other semiotic resources in the construction of public spaces [...] is a crucial nexus of meaning-making in the COVID-19 pandemic” (Lou et al., 2021). This evidence has prompted numerous scholars to explore, for example, translation choices and accessibility issues to information related to the pandemic (Hopkyns and Van den Hoven, 2021; Lees, 2021), linguistic, and semiotic strategies adopted for commercial or regulatory purposes (Ahmad and Hillman, 2021; Strandberg, 2021), as well as the emergence of new discourses in different linguistic and semiotic landscapes.

Scollon and Scollon (2003, p. 210) define the discourse “in the narrow sense, language in use; in the broader sense, a body of language use and other factors that form a “social language”” (Scollon and Scollon, 2003, p. 210). Therefore, discourse is seen not only as a theory, as a way of representing and communicating social practices, but also as a social practice itself. By adopting this perspective, discourses are interpreted at the same time as tools for the social construction of reality and as action, i.e., as instruments of control and power (Van Leeuwen, 1993, 2008).

In a geosemiotic analysis of the urban space, signs can be part of some discursive categories (which influence each other). These include regulatory discourses, which tend to mediate mobility and traffic and also serve to “inform the public either about conditions or regulations that are present in that place” (Scollon and Scollon, 2003, p. 184); infrastructural discourses, which work in support of urban resources, such as roads, electricity, gas, and water; commercial discourses, which clearly indicate the presence of activities or their products; and transgressive discourses, which are those “out of place,” often placed in marginalized places or, on the contrary, overexposed. The signs that constitute the LL convey these (and other) discourses, intersecting and overlapping each other, combining to form a semiotic aggregate, and making sure that “discourse(s) shapes and is shaped by the linguistic landscape(s)” (Seargeant and Giaxoglou, 2020, p. 311).

Taking into consideration the emergence of pandemic-related discourses, Panagiotatou (2021) explores the Berlin LL during the so-called second wave. Her aim is to identify the complex relationships between LL and COVID-19, considering the local specificities in terms of superdiversity and the subcultures present. From her analysis, it emerges how public signs and signs of protest coexist, reflecting and in turn reproducing different ideologies. She also notes how, in the face of a top-down effort to create a homogeneous identity and a sense of collectivity, a plurality of voices, often contradictory, emerge from the bottom. Together these voices transform “the LL of Berlin into an arena of contestation and presents [sic] the city as a site of conflict and exclusion” (Panagiotatou, 2021, p. 173). A plurality of voices also emerges from Marshall (2021), who examines the change in the Vancouver LL during the “first wave” of the pandemic. Although this polyphony of voices manifests itself in very different ways, the scholar observes a discursive convergence between top-down and bottom-up signs. The latter, in particular, is made up of grassroots semiotic artifacts, that is, colored stones that promote messages of solidarity and kindness, in line with the dominant political discourse. It is, therefore, affective-discursive practices that can be defined as forms of linguistic “recruitment, articulation, or enlistment... [when] bodies, subjectivities, relations, histories, and contexts entangle and intertwine together to form just this affective moment, episode, or atmosphere” (Wetherell, 2015, p. 160). The increasing attention paid to the exploration of discursive-affective practices in the LL has led Milani and Richardson (2021) to talk about the “affective turn” in the field of study. The importance of this perspective is linked to the fact that the LL can be seen as “structuring the affective affordances and positions of individuals and groups” (Wee and Goh, 2020, p. 8). In this sense, the creation of signs is not always aimed at reflecting individual emotions, but at bringing into being a certain type of emotional atmosphere, to instill hope, spread love, and create a sense of togetherness. Since the early days of the LL field, researchers from all over the world have sought “to understand the motives, uses, ideologies, language varieties and contestations of multiple forms of “languages” as they are displayed in public spaces”1 and the pandemic has involved a distortion in all these factors, including the discursive-affective practices. In the following pages, who contributed to these changes in the Italian LL, when, and in what way will be explored.

3. Research methodology

This study adopts a mixed methods approach (Creswell, 2003, 2008): heterogeneous research tools, such as LL signs, observations, and interviews were used to answer the research questions, with collections of data stratified over time and plural analysis conducted on different levels. As anticipated, the comparison between top-down and bottom-up discourses, i.e., between the different linguistic and semiotic ways in which social actors have tried, at the same time, to represent and control the social reality, is central. In particular, three phases of the research can be distinguished.

Proceeding in chronological order, in the first wave of the pandemic, from February to April 2020, data were collected in the cyberscape. The data consisted of newspaper articles, blogs, memes, and images that had gone viral, and advertising flyers in which the COVID-19 discourse assumed relevance. The choice to focus on the virtual environment was dictated by pragmatic reasons, as the lockdown imposed at the national level prevented the researchers from engaging in linguistic walks and from collecting data in the urban LL. At the same time, however, the same limitations to which the researchers were subjected were experienced by the rest of the Italian population; regulatory, advertising, affective, and interrelation discourses had moved to the virtual environment for everyone, thus making the cyberscape not only “the only” but also the most relevant source of data related to the pandemic discourse.

The corpus of data collected in this first phase was subjected to a multimodal discourse analysis, “which extends the study of language per se to the study of language in combination with other resources” (O'Halloran, 2011, p. 120). This was considered appropriate to identify the discourses themselves linked to COVID-19, and the linguistic and multimodal strategies adopted by institutional and private citizens to convey them.

In the second and third waves of the pandemic, from September 2020 to May 2021, the research moved to the urban LL, in particular, in the city of Florence. In this phase of the research, the study was carried out on several fronts. First of all, a mapping of the historic city center was carried out, specifically, of the COVID-19 related signs, i.e., signs that, regardless of the author, materiality, or emplacement, conveyed discourses (of various types) related to the pandemic. The survey was conducted according to what has been done in other studies in the field (cf. Gorter, 2019), thus personally engaging in repeated linguistic walks and photographing the signs of interest. The corpus of images subsequently cataloged and analyzed through multimodal discourse analysis amounts to 123 signs. Second, attention was kept on the online dimension, especially in relation to the link with the physical space investigated (Maly and Blommaert, 2019). In fact, the cyberscape, in addition to being an important complement to the physical space itself, can be considered an element of the territory, with its own dynamics. In cyberscapes, linguistic and semiotic choices have relevance; they influence the symbolic dimension of organization and power and must be considered in relation to the emplacement of (digital) texts and signs.

Third, focus groups (Powell et al., 1996; Finch and Lewis, 2003) with citizens of Florence were organized and conducted, in order, among other things, to detect the degree of awareness of changes in the LL due to the pandemic (Stroud and Mpendukana, 2009). These meetings took place in the months of March–April 2021 online on the Google Meet platform (Gaiser, 2008; Stewart and Shamdasani, 2015), as the trend of infections at that time made mobility and face-to-face meetings difficult. In addition to a pilot meeting that involved 5 informants, which was not considered in the analysis phase, 21 people were interviewed, in 7 meetings, for a total of about 216 min of recording. These interviews, subsequently transcribed, were subjected to an analysis based on the principles of qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2000) through the NVivo 11 Pro software (Bazeley and Jackson, 2013). A total of 346 references were thus codified, summarized in 57 nodes, with three tree nodes (called “History and perceptions of the city of Florence,” “The subdivision of the city into districts,” and “Awareness of the Linguistic Landscape”). One of the child nodes is related to “Discourses in the LL associated to the pandemic”; the discussion in the next pages will focus on this.

Finally, in the months of September–November 2021, in a period following the third wave of the pandemic in which there was a reduction in infections, the third phase of the research took place2. It consisted of a mapping of five districts of the city of Florence (Oltrarno, San Lorenzo, Station area, Le Cure, Stadium area); the data collected included all the signs placed in the LL of these areas and not only the signs related to COVID-19. This was done in order to obtain a quantitative and not only qualitative indication of the visibility of discourses on the pandemic in the complex of the semiotic aggregate of the Florentine LL. In total, 871 photographs were collected, relating to 752 units of analysis (Cenoz and Gorter, 2006). The units of analysis that contained one or more signs related to COVID-19 discourses were found to be 151. These were analyzed within the geosemiotic framework (Scollon and Scollon, 2003) while carrying out an analysis of the discourse, and a qualitative-quantitative one, using a complex annotation grid (adapted from Bellinzona, 2021).

4. Results and discussion: The narrating LL

The analysis conducted on the different types of data collected led to the identification of heterogeneous discourses related to the pandemic, different from each other not only regarding the agents who have decided to produce and convey them, but also regarding the emplacement, the impact, and above all for the moment in time in which they materialized in the LL and the collective imagination. Precisely, the temporal criterion will guide the discussion of the results. In the next paragraphs, what emerged from the study will be explored by retracing the various waves of the pandemic in Italy, thus using the LL as if it were a logbook, a kaleidoscope of stories in history.

4.1. The first wave: Silence and hope

Since the dawn of the field of study (Gorter, 2006), research on LL has focused on the description and analysis of (multilingual and multimodal) landscapes in the awareness of the impact that visible signs in urban space can have on citizens, inhabitants, and tourists, on all those who perceive, conceive, and experience these spaces (Lefebvre, 1991; Trumper-Hecht, 2010). The mobility of people, in other words, is one of the central characteristics of the LL, although not always explicitly considered in research: it is a key active element capable of receiving and influencing the very production of space and the LL.

The outbreak of the pandemic caused a disruption of all this: overnight, with the establishment of the national lockdown, the streets, the nightlife and shopping streets, the main squares, the bars, and meeting places emptied, totally losing their functions. The absence of mobility, encounters, and exchanges that normally take place in the public space had an impact above all on the soundscape. No more traffic noise, no more voices, and no more languages—just silence. The silence was broken by the sirens of ambulances and by the loudspeakers of the authorities, who were driving around inviting citizens to stay at home. A silence was reflected in the LL itself, which went from being an open and accessible space, lived and dynamic, to being a space closed and inhibited to the public, static and suspended in time. Once emptied, the city centers were no longer of interest primarily for commercial communication. In fact, photo 1 (Figure 1)3 shows the spaces reserved for large advertising billboards in Milan that remained empty, white, and silent.

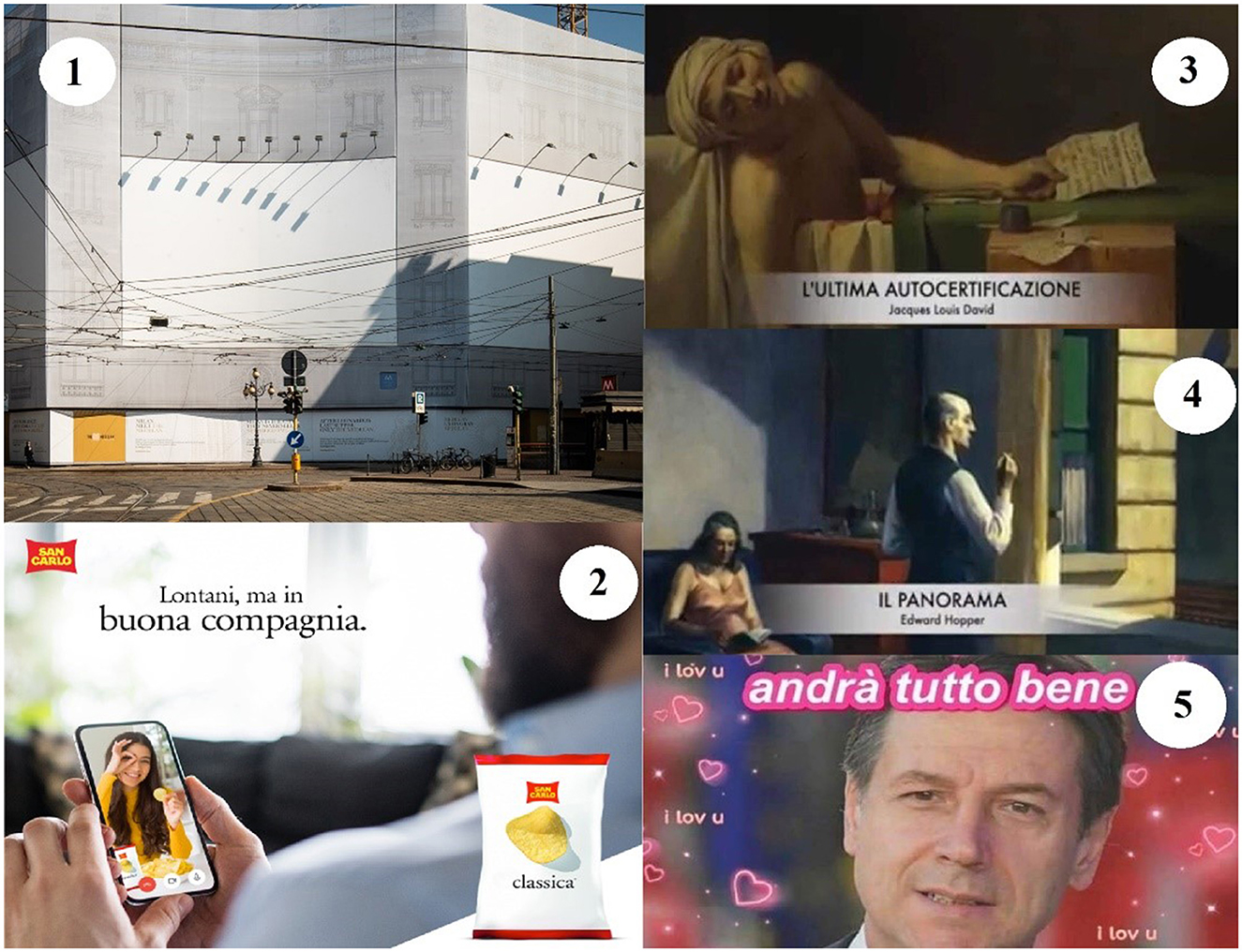

Figure 1. Photo 1—white billboards in Milan; Photo 2—San Carlo advertising with a pun; Photo 3—meme related to self-certification; Photo 4—meme linked to the visible panorama during isolation; Photo 5—meme inspired by Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte.

With citizens forced to stay indoors, companies cut investment in signage. Nonetheless, commercial discourses continued to circulate, moving into the online environment. Cyberscape, and in particular the social media message boards, thus became privileged spaces to place one's advertisements, which began to circulate through the sharing of the consumers themselves. In addition, due to the dynamics and characteristics of cyberscape (Ivkovic and Lotherington, 2009), as opposed to the cityscape, we are, therefore, witnessing in this phase a reversal of the very concept of mobility, i.e., it is no longer consumers who move and come into contact with commercial discourses, conveyed by (more or less) static signs, but the exact opposite. Discourses travel, move, and meet (more or less) static consumers in the physical space of their homes.

With people's habits having changed, it is not surprising that, in addition to the means of dissemination, marketing strategies have also changed. Several brands in Italy (but not only there—refer to, e.g., Strandberg, 2021) chose to avoid direct promotion of their products, rather spreading public safety messages, and encouraging consumers to respect the rules, protect themselves, and remain united. Photo 2 (Figure 1), an advertisement for a wellknown brand of snacks, is an example in this regard: in it, there is a man on a video call with a woman who is enjoying a potato chip. At the center of the image, it can be read “Lontani, ma in buona compagnia” (“Far, but in good company”), a sentence that plays on the possible double interpretation of “good company,” referable to both the loved ones (distant, but close thanks to technology), as well as the (good) sponsored product. The emphasis on distance from loved ones, in addition to being a fact of that period, can be read as an invitation to respect the rules imposed by the lockdown, stay at home, and observe social distancing. This interpretation leads us to see the company producing the advertising, taken as a prototypical example, as a responsible subject, showing solidarity and a sense of togetherness (Theng et al., 2021). In this way, the advertising itself, being a non-essential product or inherent to the pandemic, obtains legitimacy with the public.

In other similar advertisements, wide use of irony was observed, which was obtained both at a linguistic and semiotic level or through a combination of the two. The use of irony and humorous content was one of the main features observed in the communication on social networks during the first lockdown. During the pandemic, there was an overproduction of memes: in response to a hallucinating, terrible situation, great creativity was unleashed, through which people tried to describe the new condition they were experiencing. Photo 3 and photo 4 (Figure 1) show examples of this, as they are images of famous paintings resemantized to illustrate new phenomena and shared moods. Marat is clearly exasperated in photo 3 (in the painting by Jacques-Louis David) for yet another change in the self-declaration form4. In photo 4 (Hotel of a railway—Hopper), there is a reference to the public space, to an unusual panorama, seen from the only possible angle: a window.

Photo 5 (Figure 1) is also ironic, as it shows the meme of a close-up of Giuseppe Conte, the Italian premier at the time, retouched with hearts and surmounted by the words “Andrà tutto bene” (“Everything will be all right”—the reason of this sentence is illustrated below). The image was taken from a Facebook group called “Le bimbe di Conte,” a movement born spontaneously on social media in support of the premier and which, in a very short time, reached high numbers of followers. On the page, official communications were shared and the rules to follow were remembered, using the emblematic phrases pronounced by the Prime Minister on live TV and social networks. It is important to underline, in fact, that not only the commercial discourse, but also the information services and the regulatory discourse in general in the first wave of the pandemic had moved online and, again, in particular, on social media. The premier himself made extensive use of social networks and of a lexicon of social networks. For example, the decree by which the lockdown was established was called #iorestoacasa (#Istayathome).

The cyberscape, therefore, constituted the privileged space during the first wave of the pandemic within which to spread, and therefore study, discourses related to COVID-19. Nonetheless, urban space was always experienced by citizens, albeit in restricted mobility and in ways different from the past. In line with what was widespread in the virtual landscape, even the urban LL was characterized by a proliferation of signs, created by different subjects, with different purposes and different strategies, which conveyed affection, instilled hope, and conveyed empathy. The atmosphere that emerges from the analysis of the data collected in this phase in the LL conveys a sense of individual, but above all collective, responsibility: the signs observed in Figure 2 make it clear that their creation and location did not serve so much to reflect the emotions of single individuals, but rather to bring into being a collective emotional atmosphere, capable in turn of influencing the attitudes and, consequently, the behaviors of individuals (Van Leeuwen, 1993, 2008). As stated by Rimé (2009), in fact, when people experience strong emotions, they tend to share them with others, exchanging information but above all influencing each other's emotional states. Photo 1 (Figure 2), for example, depicts a large mural, created by the Lombardy Region, in support of the commitment and sacrifice of doctors and nurses. The discourse linked to solidarity emerges clearly on a linguistic level, with the phrase “a tutti voi … grazie!” (transl: to all of you... thank you!) which dominates the sign, and on a semiotic level, in the representation of a nurse who symbolically embraces Italy. In this case, the support to health personnel, engaged in the front line in the fight against the virus, was expressed by the (regional) authorities, but cases of banners and signs produced by private citizens who wanted to convey expressions of affection have been documented throughout the nation, thanking, and defining doctors and nurses as Italian heroes and pride5

Figure 2. Photo 1—murals from the Lombardy region to support doctors and nurses; Photo 2—patriotism in the LL; Photo 3, Photo 4, and Photo 5—“Everything will be all right” banners.

This is linked to another discourse that strongly connoted the (urban and virtual) LL in the first wave of the pandemic, namely the theme of patriotism. In fact, Italian flags were hung on every window and on every balcony (something that usually happens only in conjunction with the Soccer World Cup). The common tragedy that had struck the country served to make everyone feel closer, and more united as Italian citizens, and the LL, the closest one, that is, the homescape, was the first and most important space in which this could be made evident. It was in fact important for everyone to think and demonstrate how “Italy [was] stronger than the coronavirus” (as stated on the flag in photo 2—Figure 2).

The homescape, consisting of windows, balconies, and gates of the houses, was also the scene of the emergence of a further discourse, which characterized the first lockdown in the whole peninsula, a discourse of hope and togetherness and a discourse of corporate social responsibility (Hongwei and Lloyd, 2020). Starting from 6 March 2020, some anonymous post-its with the words “Andrà tutto bene” (“Everything will be all right”) began to appear in the streets of Lombard cities (Lombardy was the first region to be hit by COVID-19), on the shutters of closed shops, on the subway, and on walls and trees6. The initiative was immediately successful, and the message of hope went around the web and quickly ended up involving the entire nation. Colorful rainbows appeared on all balconies, accompanied by the sentence (photos 3 and 5, Figure 2) and by other expressions of affection, solidarity, and hope, such as “be brave,” “do not be afraid,” and sometimes with the hashtag #iorestoacasa (photo 4—Figure 2).

Therefore, in the first wave of the pandemic, there was a shift both in the spaces and in the landscapes dedicated to the dissemination of discourses of various kinds, as well as in the agents who were personally engaged in conveying them: private citizens, who up to that moment essentially represented the recipients of the signs, were among the most important proponents of the spreading and strengthening of affective-discursive practices. The latter, as well as commercial and regulatory signs, went hand in hand in the first phase of the pandemic, manifesting a convergence between top-down and bottom-up discourses, which were mutually reinforcing.

4.2. The second-third wave: Rules and responsibility

The long period that constituted the second-third wave of the pandemic, from September 2020 to April/May 2021, was characterized by an alternation of opening-closing of commercial establishments, of teaching face to face-online, and of mobility-immobility. The system introduced at the national level provided, as anticipated, for the use of colors from red to white, to be attributed to individual regions. The changes from one color to another, and therefore with more or less restrictive measures, were made on a weekly basis with centralized evaluations (based on the number of infections and other parameters). This constant alternation had important consequences on the LL which was characterized by the invasive presence of regulatory discourses, which were necessary to disseminate the rules to be respected to avoid the spread of the virus and to allow the regular conduct of commercial activities. As C., one of the participants in the focus groups conducted with citizens of Florence stated:

C: There has been an inversion of signs that address the new status, or new rules, outside the shops; so there is a change due to the needs of the pandemic. (08/03/2021—our translation from Italian).

Although not mandatory by law, most of the commercial establishments in the center of Florence decided, at this stage, to post signs in the window to regulate the use of spaces and prevent infections. This choice can be interpreted by referring to the concept of responsibility (Siragusa and Ferguson, 2020)—the shopkeepers, by modifying the LL, acted as mediators, promoting compliance with the rules from the bottom, legitimizing them, and thus strengthening the sense of community, put at risk by the pandemic itself. Some traders decided to use the LL in a creative way, reminding them to “use the mask,” “keep the distance,” and “disinfect hands” using semiotic elements that can refer to the type of activity itself. An example in this sense is shown in photo 1 (Figure 3), relating to a shop with pet products, in which to reinforce the indications relating to the behaviors to be followed (wear a mask and enter one at a time), some tender characters are depicted (a dog with a mask covering its muzzle and a lone hedgehog).

Figure 3. Photo 1—regulatory sign personalized based on commercial activity; Photo 2—irony in the LL; Photo 3—LL semiotically connoted; Photo 4 and Photo 5—standardized regulatory signs.

Other traders resorted to irony. In this regard, photo 2 and photo 3 in Figure 3 are prototypical. Photo 2 shows a sheet, hanging on the window of a clothing store, in which the shopkeeper sarcastically reports presumed reopening dates of the shop, barred from time to time in compliance with the decrees. In photo 3, in turn, one can see the outside of a restaurant festively decorated with yellow balloons and flags, symbolically signaling Tuscany's entry into the yellow zone, the one subject to fewer restrictions.

Most of the documented regulatory signs, however, consist of standardized signs (for example, photo 4 in Figure 2), made available online by local, regional, or national authorities and downloadable for free. These are prints, in color or black and white, of signs with a limited amount of written text, mainly in Italian or at most duplicated in English, in which the efficiency and accessibility of communication are (only partially) guaranteed by the presence of semiotic elements such as symbols and icons. The pandemic has resulted in emptying and impoverishment of the multilingualism exposed, also and above all in cities like Florence, which welcomed thousands of tourists from all over the world every day before the spread of COVID-19.

It is interesting to observe how, during the focus groups, few informants mentioned the regulatory discourses present in the LL, although the latter, as mentioned, were strongly present in the Florentine LL. This can be interpreted in at least two ways. First of all, as observed elsewhere (Bellinzona, 2021), the degree of awareness both of the linguistic diversity exhibited and of the semiotic (and therefore ideological) scope of signs in space appears limited, especially for regulatory signs, which are omnipresent, duplicated, and somehow taken for granted. Second, it is worth observing how these new signs coexist alongside others already present on the shop windows: opening hours, accepted credit cards, admission allowed (or not) to dogs, etc. They are also very often in the lower part of the showcases, near the ground, in a position far away from the one toward which one usually looks (photo 5 in Figure 3). All this leads to questioning the degree of usefulness of these signs and how much they have actually influenced behaviors and attitudes.

Conversely, other issues emerged from the analysis of the focus groups that, in many cases, aroused strong reactions in the attitudes of the interviewees. Consider in this sense what was observed by R., who drew attention to another central characteristic of this phase, which can be defined as the “Pompeii effect” (Mourlhon-Dallies, 2021). Discussing with the other focus group participants, R. stated:

R: Much fewer signs around. I don't know, but I noticed, as I passed Piazza Francia, there were areas where there were a lot of advertising signs, and there is [now] much less stuff. Another thing was the ATAF [the bus company in Florence], which had 4/5 months old advertisements: the other day an ATAF bus drove by that had an advertisement with a deadline of 31 December, 2020, so it means that no one has bought the space and they do not even take it off. It was quite shocking. (25/03/2021—our translation from Italian).

The LL, in other words, remained frozen and suspended, giving a snapshot of time and life prior to the outbreak of the pandemic. It is the moment in which the most tangible signs of the past were observed, and it is the moment in which infrastructural discourses linked to COVID-19 began to emerge with more force. Interesting was what F. stated:

F: COVID-19 has really caused a major change that still makes me very upset. Maybe in Florence, you notice it less. But when you arrive at a big city like Milan, along the external ring road, and you read in the luminous panels that normally indicate the queue or the traffic, you read “drive- through COVID-19 [tests] exit so and so”. Or when you find these enormous panels indicating the vaccination hub, it is something that still makes you think and takes you into a reality that is truly unusual for us and to which it is really hard to get used to. (02/04/2021—our translation from Italian).

Among the most discussed issues identifiable within the node “Discourses in the LL related to the pandemic,” there is also a reference to the economic crisis, a direct consequence of the health crisis. Several informants, in fact, mentioned changes in the LL due to this, referring to the linguistic and more generally semiotic impoverishment of the urban landscape as a reflection of the closure of numerous shops or the absence of tourists. There are those who, like T., reported having noticed a proliferation of signs bearing the indication “for sale” and “rent,” and who, like D. (within the same group), stated that:

D: It was difficult, not being able to go out... mostly the classic tourist places, many have gone bankrupt, restaurants that have shut down, so... As there are no more tourists, there are no more menus in two languages. (08/03/2021—our translation from Italian).

In turn, A., joining the discussion, shifted the focus to transgressive discourses and street art which, in his opinion, can be a representative domain of trends, including ideological ones, within society.

A: Maybe Street art, which talks about everyday life, problems, may have been affected by the economic crisis, so there may be more references to issues of social justice, direct or indirect consequences of the economic crisis, layoffs, etc. (08/03/2021—our translation from Italian).

This reference to street art turned out to be in some way prophetic of what was observed in the last phase of the research. While the survey carried out during the second and third waves of the pandemic did not lead to the identification of a significant number of transgressive signs carrying discourses about the pandemic, in the following period, this was not the case. In the next section, we will explore this specific aspect.

4.3. The quiet (before the storm): Stratification and contradictions

The months from May to November 2021 granted a truce regarding the circulation of the virus in Italy7. This truce was partially obtained due to the measures of social distancing, isolation, and individual protection, as well as the mass vaccination campaign. Despite this, during those months, the discontent of a part of the population grew, exasperated by the restrictive measures, the economic crisis, and the obligation of the Green Pass and vaccine8. This discontent resulted in protests and demonstrations both online and in the streets of the cities and was immediately reflected in the LL. As anticipated, in this phase of the pandemic, data from the LL in five districts of Florence were systematically collected. In total, 151 units of analysis (20% of the total) containing various types of discourses relating to the pandemic were documented. Among these, there was, first of all, a transgressive discourse, which clearly shows the atmosphere of dissatisfaction and protest. Consider, for example, photos 1, 2, and 3 in Figure 4. Photo 1 shows the tag “COVID 1984”, made with a stencil on a wall in the center of Florence. It is a reference to Orwell's dystopian novel “1984,” to the control over the population that is exercised in it, and to conspiracy and totalitarian ideologies. It was used by supporters attributable to No Vax area groups for the campaign to contest government measures. Similarly, in photo 2, one can read “siamo più di un assembramento” (“we are more than a gathering”), sprayed on the wall. The pandemic, as already mentioned in this contribution and as observed elsewhere (Spina, 2020; Papp, 2021; inter alia), had also affected the language, which evolved and changed, first of all on the lexical level, leading to a “terminological pandemic.” The term “assembramento” (gathering) is one of those that entered the family lexicon of the pandemic following its use in the Prime Minister's decrees and speeches during the first wave of COVID-19. In the graffiti in the photo, the terminological choice is not accidental, nor is the textual formulation itself, which hides a conversational implicature (Grice, 1975). Claiming to be more than a gathering, the anonymous writer suggests that there is someone (presumably the media and the government, those who use the term “gathering”) who sees sociality, being in a group, only as a means of disseminating the virus. By prohibiting it, people's freedoms are limited and they are prevented from exercising their rights.

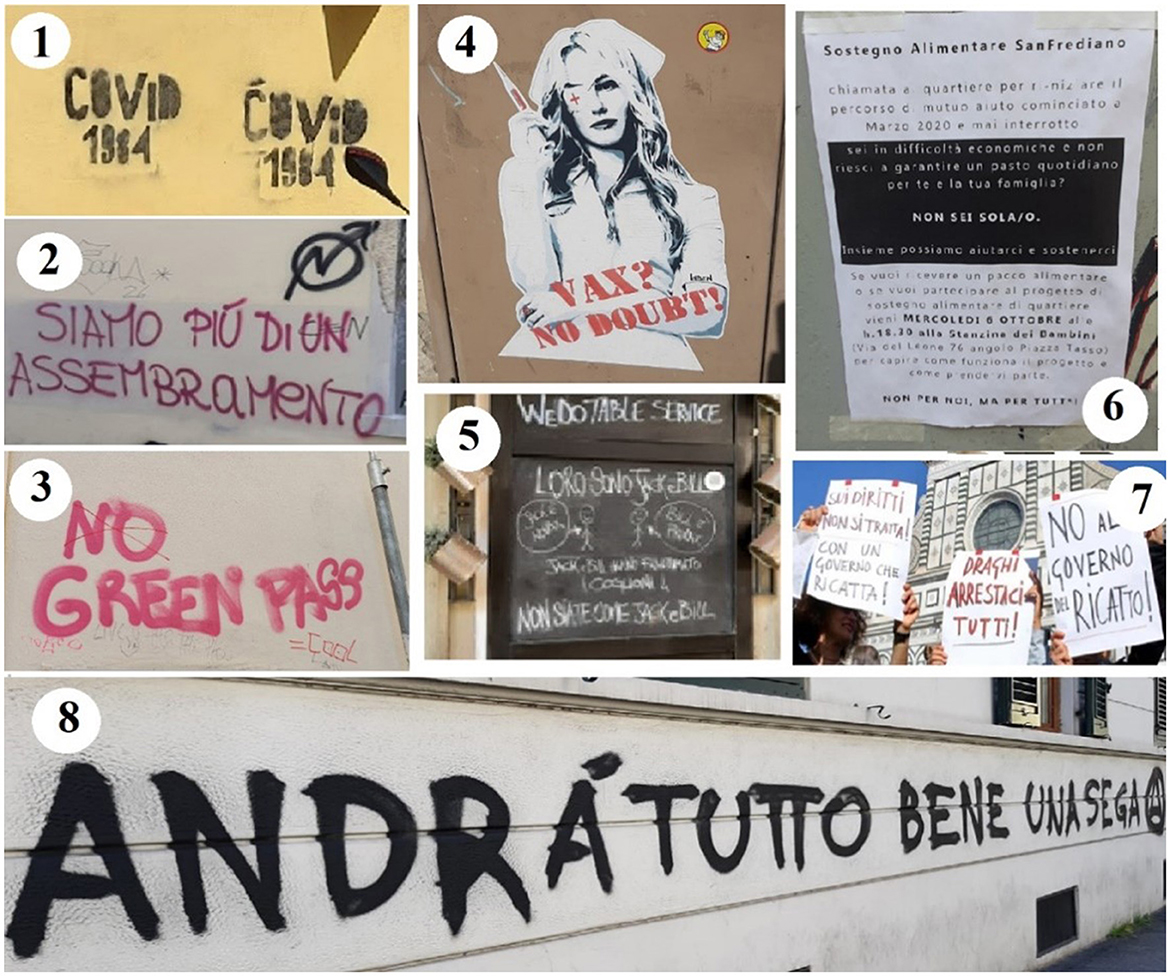

Figure 4. Photo 1—tag “COVID 1984”; Photo 2—graffiti “we are more than a gathering”; Photo 3—protest, dialogue, and stratification in the LL; Photo 4—stencil art “Vax? No doubt¡‘; Photo 5—meme reworked on blackboard; Photo 6—leaflet for food support; Photo 7—protest signs of a demonstration in the square; Photo 8—graffiti “everything will be all right my ass”.

The text in photo 3, in contrast, is explicit, as it reports graffiti with “No Green pass,” the document required to access certain services and, in some cases, to work. The image appears to be interesting as it allows us to reflect, among other things, on stratification and dialogue, two key characteristics of the LL (Blommaert, 2013). As can be seen, in fact, the wording “No,” part of the original text, was later crossed out by another person, evidently in favor of the Green Pass obligation.

In favor of the vaccine is also Laben, a Tuscan street artist and author of the work in photo 4 (Figure 4). It is a work in stencil art (attached with vinyl glue to the service booths, with a “paste up” technique, respecting the buildings and the city), in which Elle Driver by Tarantino is represented with a syringe and the writing “Vax? No doubt!.” The artist, with this and other works documented in the different mapped neighborhoods, wants to raise awareness of the importance of the vaccine and to reflect on the doubts that exist in society about its efficacy and safety.

The debate on the Green Pass and vaccination obligation was so intense that in some cases, it was no longer tolerated. In photo 5 (Figure 4), there is a blackboard, placed outside a pub in the center, in which a famous meme has been reproduced. There are two people, Jack and Bill, one pro-vax and the other no-vax: the sign maker's comment, however, distorts the very dynamics of the meme, making clear what was stated above. It reads, in fact, “Loro sono Jack e Bill—Jack è novax—Bill è pro vax—Jack e Bill hanno frantumato i coglioni! Non-siate come Jack e Bill” (transl: They are Jack and Bill—Jack is no-vax—Bill is pro-vax—Jack and Bill have busted our balls! Do not be like Jack and Bill”).

This transformation in the debate, and the perception of the debate, offers us the opportunity to briefly discuss the evolution of social discourses related to the pandemic and how these have changed the LL itself in the last period taken into consideration. The discourses observed during the first wave of the pandemic, in fact, continued to manifest themselves in the virtual and urban LL, but changing connotations. Consider, for example, the discourse linked to solidarity which, in the first wave, was directed above all to doctors and nurses. The analysis of the data collected in Florence shows how solidarity in the LL continues to find space but with a different meaning. This is a smaller range of solidarity, as it is expressed in favor of neighbors and neighborhood members. There are no more heroes, but victims of the system. Photo 6 (Figure 4) is an example of this: in it, one can see a poster promoting mutual aid among the inhabitants of the neighborhood for food support, a service activated in March 2020 and never interrupted.

One of the dominant discourses in the first wave of the pandemic was also linked to patriotism and trust in institutions (think of the “le Bimbe di Giuseppe Conte” or the Italian flag hanging on the windows). During the survey conducted in the Florentine neighborhoods, no Italian flags were hanging on the windows, and the transitional LL of a demonstration against the obligation of the Green Pass (photo 7—Figure 4)9 offers an insight into diametrically opposite discourses. Mario Draghi, the new Prime Minister, does not enjoy the success of his predecessor among the demonstrators and his government is defined as “del ricatto” (“blackmail”). The patriotic discourse persists, but Italy itself is no longer seen as strong and united. It is a Country in danger, not due to the spread of a lethal virus, but because, according to the demonstrators, the measures adopted by the government threaten our freedom.

Finally, one of the most immediately recognizable consequences of the protracted health emergency was the gradual disappearance of messages of hope. Banners with rainbows and “everything will be all right” messages were removed, to make room for messages of despair and disillusionment. In some cases, they refer directly to the iconic phrases of the first wave, as in the graffiti in photo 8 (Figure 4), which reads “andrà tutto bene una sega” (“everything will be all right my ass”). Hence, the question mark added to the title of this article at the end of the sentence that most of all characterized the discourse on COVID-19 in Italy.

5. Concluding remarks

In this chapter, we have tried to offer an overview of the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the Italian LL in general and specifically in the city of Florence. The different data collections, stratified over time, have made it possible to reconstruct the mosaic of discourses that have characterized written communication in the public, urban, and virtual space, restoring an unprecedented image of the 2-year period 2020–2021 in Italy. The analysis and the proposed discussion, in turn, made it possible to answer the research questions formulated, leading, first of all, to the identification of the discourses on the pandemic that emerged in its various phases. Second, they led to a reflection on the actors of the LL, being these sign-makers and issuers who have conveyed those discourses. Moreover, they provided feedback on the perceptions and awareness of the readers of the signs when such discourses emerge.

Collecting data in the different phases of the pandemic was a winning choice, which gave us the opportunity to use the LL as a narrative site to observe the unfolding of stories (and history). The rapid evolution that the LL has undergone reminds us once more of how important it is to always frame and base studies on a historical and diachronic level (Blommaert, 2013), contextualizing the data we collect and the analyses we do at the precise historical moment in which we act, with all the consequences that derive from this.

Similar to others before us (Lees, 2021; Marshall, 2021), we have observed the appearance of a new kind of signs in the urban LL, i.e., signs that explain the new rules to be followed and provide information to the public in order to prevent the spread of the virus. This is a new regulatory discourse, which includes traits of the political and juridical discourse, of the medical-health one, but also of the emotional (and sometimes of the commercial) one. Taking into consideration commercial establishments, the decision to display signs of this type in the window could be read in two possible ways. On the one hand, since it was not required by law, it is an indication of the responsibility of the shopkeepers (Siragusa and Ferguson, 2020). On the other hand, it can be defined as a new way of offering oneself to the public, no longer and not so much as tourist-friendly, rather as COVID-free shops. At the same time, however, the very location of these signs, often in black and white, hidden away and inserted in larger semiotic aggregates, as emerged from the second and above all from the third phase of the research, calls into question the importance of these discourses both for issues of prevention and promotion. This aspect is confirmed by the data related to the awareness of the presence of this new textual genre, an awareness that, from the analysis of the focus groups, appeared extremely limited.

Conversely, the perception of the changes in the linguistic and semiotic urban landscape as a consequence of the pandemic was varied and shed light on some characteristic elements of the period, from the temporal suspension of the LL (the so-called Pompeii effect, Mourlhon-Dallies, 2021) to the emotional shock brought about by the appearance of new infrastructural and medical discourses, passing through transgressive, protest, and social justice discourses.

To conclude, the results of this study offer a photograph of complex landscapes and ecologies, which are multilingual, multimodal, multi-layered, and interactive, demonstrating once again the usefulness of an analysis of the LL, even and especially in periods of crisis, to reflect on heterogeneous linguistic and social facts.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

CB takes responsibility for Section 1. MB for Sections 2–4. Concluding remarks are shared. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Introduction of the International Journal of Linguistic Landscape https://benjamins.com/catalog/ll (26/06/2022).

2. ^Further data were collected until January 2022. These, however, were not considered for the quantitative analysis, as they only concerned signs containing discourses on the pandemic, as was done for the second phase of the research.

3. ^https://www.infomilano.news/muri-bianchi-a-milano-senza-pubblicita/ (27/07/2022).

4. ^The self-declaration consisted of a pre-set form to be filled in and presented during police checks to justify travel. This form has changed numerous times (five times from 8 March to 26 April 2020) to adapt to the new decrees and changes in the restrictive measures.

5. ^For example, https://www.forlitoday.it/cronaca/striscione-coronavirus-ospedale-forli.html (22/07/2022).

6. ^https://milano.repubblica.it/cronaca/2020/03/06/foto/coronavirus_post_it_tutto_andra_bene_lombardia-250317657/1/ (24/07/2022).

7. ^In December 2021, the numbers of infections started to rise again, hence the title given to the paragraph.

8. ^The Green Pass is a digital certification created following a proposal from the European Commission to facilitate a free (safe) movement of EU citizens during the pandemic. It certifies the vaccination, the negative result of a COVID test or the successful recovery from the virus.

9. ^https://www.firenzetoday.it/video/no-green-pass-firenze-15-ottobre.html (22/07/2022).

References

Adami, E., Al Zidjaly, N., Canale, G., Djonov, E., Ghiasian, M. S., Gualberto, C., et al. (2020). PanMeMic manifesto: making meaning in the COVID-19 pandemic and the future of social interaction. Working Papers in Urban Language and Literacies, 273.

Ahmad, R., and Hillman, S. (2021). Laboring to communicate: use of migrant languages in COVID-19 awareness campaign in Qatar. Multilingua 40, 303–337. doi: 10.1515/multi-2020-0119

Bagna, C., Bellinzona, M., and Monaci, V. (forthcoming). “Linguistic landscape between concrete signs citizens perceptions. Exploring sociolinguistic semiotic differences of Florence districts,” in Sociolinguistic Variation in Urban Linguistic Landscapes, eds S. Henricson, V. Syrjälä, C. Bagna, M. Bellinzona (Uusimaa: Finnish Literature Society).

Bellinzona, M. (2021). Linguistic Landscape. Panorami Urbani e Scolastici Nel XXI Secolo. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Blommaert, J. (2013). Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes: Chronicles of Complexity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. doi: 10.21832/9781783090419

Cenoz, J., and Gorter, D. (2006). “Linguistic landscape and minority languages,” in Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism, ed D. Gorter (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 67–80. doi: 10.21832/9781853599170-005

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Research, 3rd Edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Pearson Education.

Finch, H., and Lewis, J. (2003). “Focus groups,” in Qualitative Research Practice, eds J. Ritchie, and J. Lewis (London: Sage Publication), 170–198.

Gaiser, T. J. (2008). “Online focus groups,” in The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods, eds N. J. Fielding, R. M. Lee, and G. Blank (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications), 290–306. doi: 10.4135/9780857020055.n16

Gorter, D. (2006). Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. doi: 10.21832/9781853599170

Gorter, D. (2012). “Foreword: signposts in the linguistic landscape,” in Linguistic Landscapes, Multilingualism and Social Change, eds C. Hélot et al. (Frankfurt: Peter Lang), 9–12.

Gorter, D. (2019). “Methods and techniques for linguistic landscape research: about definitions, core issues and technological innovations,” in Expanding the Linguistic Landscape: Linguistic Diversity, Multimodality and the Use of Space as a Semiotic Resource, eds M. Pütz and N. Mundt (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 38–57. doi: 10.21832/9781788922166-005

Gotham, K. F. (2005). Tourism gentrification: the case of new Orleans' vieux carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 42, 1099–1121. doi: 10.1080/00420980500120881

Grice, H. P. (1975). “Logic and conversation,” in Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3, Speech Acts, eds P. Cole et al. (New York, NY: Academic Press), 41–58.

Hongwei, H., and Lloyd, H. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 116, 176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.030

Hopkyns, S., and Van den Hoven, M. (2021). Linguistic diversity and inclusion in Abu Dhabi's linguistic landscape during the COVID-19 period. Multilingua 42, 201–232. doi: 10.1515/multi-2020-0187

Ivkovic, D., and Lotherington, H. (2009). Multilingualism in cyberspace: conceptualising the virtual linguistic landscape. Int. J. Multiling. 6, 17–36. doi: 10.1080/14790710802582436

Lees, C. (2021). “Please wear mask!” COVID-19 in the translation landscape of Thessaloniki: a cross-disciplinary approach to the English translations of Greek public notices. Translator 28, 344–365. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2021.1926135

Lou, J. J., Peck, A., and Malinowski, D. (2021). The Linguistic Landscape of COVID-19 Workshop: Background. Available online at: https://www.covidsings.net/background (accessed July 22, 2022).

Maly, I., and Blommaert, J. (2019). Digital Ethnographic Linguistic Landscape Analysis (ELLA 2.0). Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies 233, 1–25. Tilburg: Tilburg University.

Marshall, S. (2021). Navigating COVID-19 linguistic landscapes in Vancouver's North Shore: official signs, grassroots literacy artefacts, monolingualism, and discursive convergence. Int. J. Multiling. 18, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2020.1849225

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 1, 1–10. doi: 10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089

Milani, T. M., and Richardson, J. E. (2021). Discourse and affect. Soc. Semiot. 31, 671–676. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2020.1810553

Mourlhon-Dallies, F. (2021). The COVID-19 Pandemic on Display: Multiple Temporalities in Paris. Available online at: https://www.covidsigns.net/post/florencemourlhon-dallies-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-display-multiple-temporalities-in-paris (accessed July 22, 2022).

O'Halloran, K. L. (2011). “Multimodal discourse analysis,” in Companion to Discourse Analysis, eds K. Hyland, and B. Paltridge (London: Continuum), 120–137.

Panagiotatou, E. (2021). COVID-19 and the linguistic landscape of Berlin. Aegean Work. Papers Ethnogr. Ling. 3, 159–175. Available online at: https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/awpel/article/view/29954

Papp, J. (2021). Il nostro lessico è diventato “virale”. Il vocabolario dell'emergenza sanitaria, economica e sociale ai tempi della pandemia di COVID-19. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai. Philol. 66, 325–344. doi: 10.24193/subbphilo.2021.1.22

Powell, R. A., Single, H. M., and Lloyd, K. R. (1996). Focus groups in mental health research: enhancing the validity of user and provider questionnaires. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 42, 193–206.

Rimé, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: theory and empirical review. Emot. Rev. 1, 60–85. doi: 10.1177/1754073908097189

Scarvaglieri, C., Redder, A., Pappenhagen, R., and Brehmer, B. (2013). “Capturing diversity: linguistic landand soundscaping,” in Linguistic Superdiversity in Urban Areas: Research Approaches, eds J. Duarte, and I. Gogolin (Philadelphia: John Benjamins), 45–74. doi: 10.1075/hsld.2.05sca

Scollon, R., and Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203422724

Seargeant, P., and Giaxoglou, K. (2020). “Discourse and the linguistic landscape,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Discourse Studies, eds A. De Fina, and A. Georgakopoulou (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 306–326. doi: 10.1017/9781108348195.015

Siragusa, L., and Ferguson, J. K., (eds). (2020). Responsibility and Language Practices in Place. Helsinki: SKS. doi: 10.21435/sfa.5

Spina, S. (2020). Raccontare il coronavirus attraverso le parole. Il lessico della pandemia usato dalla stampa da febbraio a ottobre 2020. IL Bollettino di CLIO XVIII, 107–115.

Stewart, D. W., and Shamdasani, P. N. (2015). Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Sage publications.

Strandberg, J. A. E. (2021). Solidarity for Sale: Corporate Social Responsibility and Newsjacking in Global Advertising During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.covidsigns.net/post/janine-strandberg-solidarity-for-sale (accessed July 22, 2022).

Stroud, C., and Mpendukana, S. (2009). Towards a material ethnography of linguistic landscape: multilingualism, mobility and space in a South African township 1. J. Socioling. 13, 363–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00410.x

Theng, A., Tse, V., and Wu, J. (2021). Who is Included in “Together”? Conflicting Senses of Responsibility in the Hong Kong COVID-19 Landscapes. Available online at: https://www.covidsigns.net/post/theng-tse-wu (accessed July 22, 2022).

Trumper-Hecht, N. (2010). “Linguistic landscape in mixed cities in Israel from the perspective of “walkers:” The case of Arabic,” in Linguistic Landscape in the City, eds E. Shohamy, E. Ben-Rafael, and M. Barni (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 235–251. doi: 10.21832/9781847692993-015

Van Leeuwen, T. (1993). Genre and field in critical discourse analysis: a synopsis. Disc. Soc. 4, 193–223.

Van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. New York, NY: Oxford university press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195323306.001.0001

Wee, L., and Goh, R. B. H. (2020). Language, Space and Cultural Play: Theorising Affect in the Semiotic Landscape. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108559515

Keywords: linguistic landscape, language contact, COVID-19, discourses, multimodality

Citation: Bagna C and Bellinzona M (2023) “Everything will be all right (?)”: Discourses on COVID-19 in the Italian linguistic landscape. Front. Commun. 8:1085455. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1085455

Received: 08 November 2022; Accepted: 10 February 2023;

Published: 07 March 2023.

Edited by:

Justyna Robinson, University of Sussex, United KingdomReviewed by:

Mary Macken-Horarik, Australian Catholic University, AustraliaPaolo Coluzzi, University of Malaya, Malaysia

Copyright © 2023 Bagna and Bellinzona. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carla Bagna, bagna@unistrasi.it; Martina Bellinzona, martina.bellinzona@unistrasi.it

Carla Bagna

Carla Bagna Martina Bellinzona

Martina Bellinzona