Emerging Pathophysiological Mechanisms Linking Diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Old Wine in a New Bottle

Abstract

Type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic immuno-inflammatory and metabolic disease characterized by hyperglycemia and insulin resistance with corresponding hyperinsulinemia. On the other hand, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease involving cognitive impairment, neuronal dysfunction, and memory loss. Several recently published literatures suggest a causal relationship between T2DM and AD. In this review, we have discussed several potential mechanisms underlying diabetes-induced cognitive impairment which include, abnormal insulin signaling, amyloid-β accumulation, oxidative stress, immuno-inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, advanced glycation end products, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase, advanced lipid peroxidation products, and apolipoprotein E. All these interconnected mechanisms may act either individually or synergistically which eventually leads to neurodegeneration and AD.

INTRODUCTION

A growing body of clinical and epidemiological research suggests that two of the most common diseases of aging: type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are linked together. T2DM is characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from several metabolic defects, including impaired β-cell function, defective insulin secretion, increased hepatic glucose production, and reduced glucose utilization due to peripheral organ-specific insulin resistance. Impairment in insulin secretion and β-cell function are generally present in patients with T2DM and individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. Shreds of evidence indicate that despite continuous treatments with anti-diabetic drugs, there is a progressive deterioration in β-cell function and insulin secretion over time in T2DM [1]. On the contrary, AD is the most common form of dementia among the elderly and is characterized by progressive loss of memory and cognition with sporadic nature. The cause of sporadic AD remains unknown, yet it is associated with several risk factors, of which metabolic disorders such as diabetes stand as the strongest risk factor for development of AD [2].

According to a cohort study conducted by Wang et al., the incidence of AD was found to be 1.45 times higher in diabetics compared to non-diabetics [3]. Another study carried out by Arvanitakis and co-workers in 2004 showed a 65% increase in the risk of development of AD in patients with diabetes [4]. The risk of developing dementia is doubled in T2DM patients and is quadrupled in patients dependent on insulin [5]. A new term type-3 diabetes (T3D) coined by de la Monte and Wands is currently used in diabetic patients who develop AD [6]. T3D is also known as ‘Brain-specific type-2 diabetes’ [7] and is a neuroendocrine disorder that represents the progression of T2DM to AD. In T3D, either decreases in the production of insulin and resistance to insulin occurs [5]. In a study carried out by de la Monte and Wands in a postmortem brains of diabetic patients, they found that impairments of insulin like growth factor (IGF) signaling lead to deficits in energy metabolism with correspondingly increased oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction cum stress, proinflammatory cytokine activation and production, immune mediated inflammation, and further leading to neuronal degeneration [6]. There are some molecular denominators responsible for bridging T2DM with AD such as insulin, amyloid-β (Aβ) protein, advanced glycation end products (AGEs), acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), oxidative stress, advanced lipid peroxidation products, immuno-inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) overactivity. All these interrelated mechanisms might act synergistically and/or amplify each other signals to promote the progression of T2DM to AD. There is an increased risk of both vascular and degenerative dementia in patients with uncontrolled diabetes as well as an increased risk of AD in patients with borderline diabetes without major vascular co-morbidities [8].

BRIDGING DIABETES MELLITUS WITH ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Insulin

Insulin is secreted by pancreatic β-cells in response to glucose. It is proposed that peripheral insulin migrates to the brain via transporters crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB), while insulin is also de novo synthesized in the brain [9]. It has also been shown that peripheral infusion of insulin leads to an increase in the insulin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) suggesting that insulin can indeed cross BBB [10]. Insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) is present in various brain regions including multiple cortical areas, hippocampus, cerebellum, brain stem, oligodendrocytes, choroid plexus, etc. This enzyme degrades insulin and amyloid in normal conditions, but in case of IDE inhibition or deficiency, it results into increased insulin levels and enhanced amyloid plaque formation with correspondingly increased deposition of amyloid plaque which ultimately cause neuroinflammation and oxidative stress that promotes neuronal apoptosis. Therefore, IDE is responsible for modulating the metabolism of insulin and the deposition of amyloid [11, 12]. Insulin has also been found to play a role in several processes such as glucose homeostasis, feeding behavior, energy expenditure, self-proliferation and differentiation, neuroprotection, cognition, and memory [13].

Insulin receptors (IR)

IR comprises of two isoforms IR-A (Insulin receptor A) and IR-B (Insulin receptor B) that are encoded by gene INSR (Insulin receptor) which is located on chromosome 19 and has 22 exons and 21 introns [14]. Due to a variety of reasons, insulin receptors located in the periphery differs from that in the brain. This difference is mainly seen in the size of α subunits, glycosylation, binding capacity, and distribution patterns. IR is irregularly distributed in several areas of the central nervous system (CNS) such as the hypothalamus, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, choroid plexus, and olfactory bulb [15]. IR belongs to the tyrosine kinase family, mainly involved in signal transduction by phosphorylation of cellular substrates like insulin receptor substrates 1 and 2 (IRS-1 and IRS-2). IRS-1 maintains body growth and peripheral insulin actions, while IRS-2 regulates glucose homeostasis, brain growth, and fertility [9]. IGF receptors also belong to tyrosine kinase-linked receptor family and have two subtypes IGF-1R (IGF-1 receptor) and IGF-2R (IGF-2 receptor). Insulin and IGF1 have binding specificity towards both IR and IGF1R with different affinity, respectively, whereas IGF2R generally binds to IGF2 and does not bind to insulin [15]. IGF receptors, located in the hippocampus, temporal lobe, and diencephalon, and IGF receptors are also the most susceptible targets of AD-associated neurodegeneration [16]. Insulin and IGF-1R are associated with other pathologies that could make a bridge between T2DM and AD, mainly because of IGF-1R activation leads to activation of several cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) which promotes the excessive oxidative stress in the brain tissue [17].

Impaired insulin signaling

Insulin resistance is due to an improper response to insulin stimulation leading to excessive secretion of insulin which results into hyperinsulinemia associated retardation of various CNS activity [17]. Impaired brain insulin signaling can be implicated by several proposed mechanisms which include: 1) Hyperphosphorylation of tau; 2) GABA activation via insulin; 3) Na+/K+ ATPase; and 4) NMDA receptor activation which are interconnected with each other.

Initially, insulin binds to the α-subunit of the IR, activates β-subunit tyrosine kinase activity by phosphorylation, and leads to the activation of second messenger transduction pathways. Brain insulin and IGF resistance result in reduced signaling via phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), Akt, and Wnt/b-catenin, which are accountable for increased activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) [15]. Similarly, GABA receptor is a substrate of Akt phosphorylation which is directly or indirectly regulated by insulin signaling. GABA-A receptor is stimulated by insulin which leads to synaptic inhibition in several areas of the brain [17]. Likewise for other mechanism insulin has been reported to stimulate Na+/K+ ATPase pump by reducing both intracellular Na+ and extracellular K+ which alters the neuronal firing rate by elevating intracellular Ca++ concentration. Insulin in the hypothalamic neurons stimulates Na+/K+ ATPase, producing membrane hyperpolarization resulting into inhibitory effect on nearby neurons. Due hyperpolarization, activation of glutamate NMDA receptor has been observed which leads to Ca++ entry at the postsynaptic sites, stimulating the influx of Ca++ and activating Ca++ sensitive protein kinases like Serine/threonine-protein kinase such as protein kinase C, Calcium modulating protein (calmodulin) dependent kinase-2 (CaMKII), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAP kinases) and Akt [17, 18]. Overactivation of GSK-3β occurs as an action of variety of protein kinases which is partly responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of tau, which leads to tau misfolding and fibril aggregation enhancing neurofibrillary tangle formation and ultimately neuroinflammation and degeneration. Insulin regulates extracellular secretion and intracellular deposition of Aβ and degrades IDE activity. Due to impaired insulin signaling, there is an imbalance between amyloid formation and clearance leading to its accumulation in several brain regions. This accumulation of Aβ intervenes with the activation of PI3K kinase-mediated activation of the Akt pathway, resulting in excessive stimulation of GSK-3β and hyperphosphorylation of tau [15]. Chatterjee et al. studied the effect of insulin resistance on tau protein and further observed that insulin resistance can lead to hyperphosphorylation of tau protein by Akt and GSK-3β pathway [19].

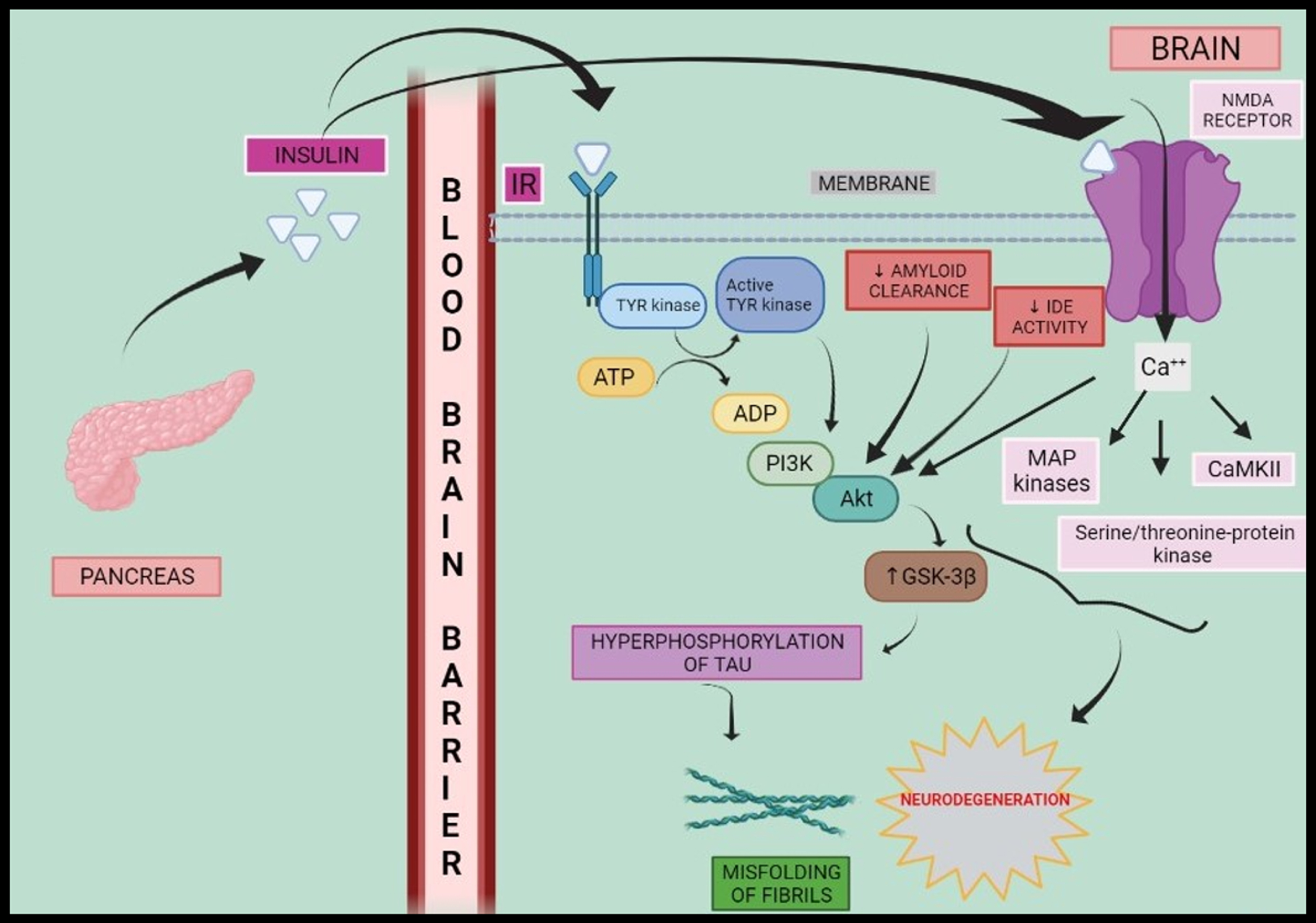

Hence, insulin, amyloid, GABA, Na+/K+ ATPase, intracellular Ca++, and glutamate NMDA synergistically activate cascade of protein kinases resulting in hyperphosphorylation and progression towards AD as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

Schematic representation of insulin signalling and neurodegeneration. Peripheral hyperinsulinemia causes insulin to cross blood-brain barrier where it binds to IR and elicits a series of reactions such as phosphorylation of Tyrosine kinase and activation of PI3K-Akt as well as MAP kinases, serine/threonine-protein kinase, CaMKII which in turn elevates activity of GSK-3β and fasten the progresses to neurodegeneration via hyperphosphorylation of tau protein. IR, insulin receptor; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; Tyr kinase, tyrosine kinase; IDE, insulin degrading enzyme; PI3K, phosphoinositol-3-kinase; MAP kinase, mitogen activated protein kinase; CaMKII, calcium modulating protein dependent kinase-2; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; NMDA receptor, N-methyl D-aspartate receptor.

Amyloid-β protein

Aβ is a 40–42 amino acid containing protein that is generated from its precursor, the amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP), by β-secretase-1 (BACE-1) along with β- and γ-secretase complexes [17, 20]. The function of α-secretase is to convert AβPP into soluble AβPPα which prevents generation of Aβ protein. The APP gene is located on chromosome 21 in humans and consists of three isoforms namely: APP695, APP751, and APP770 [21]. The function of AβPP along with amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP-2) is to maintain learning and memory [22]. In the brains of AD patients, the levels of AβPP are elevated which increases Aβ deposition along with prolonged activation of extra synaptic NMDA receptors in neurons [21]. However, in diabetic condition islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), also referred to as amylin, is produced by pancreatic β-cells that contribute to maintain physiological glucose levels by modulating insulin and glucagon secretion. Insulin and IAPP are co-secreted and processed by pro-protein convertase PC 1/3, PC 2, and carboxypeptidase E and co-packed together in secretory granules of β-cells which then released in response to change in endogenous glucose level. IAPP is a highly amyloidogenic polypeptide that forms intracellular aggregates and amyloid structures in the β-cells leading to cell death. IAPP mainly affects cognitive function and causes BBB impairment. It also tends to interact and aggregate with Aβ peptides and thereby hyperphosphorylates of tau protein within the brains of AD patients which ultimately leads to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles [23]. Arya et al (2019) established molecular interaction between tau protein and IAPP which possibly links diabetes with AD [24]. Baram et al. [25] reported that diabetic patients identified amylin deposits in the temporal lobe of gray matter— a major component of the central nervous system. Along with amylin or amyloid deposition in the human brain, amylin and Aβ aggregates collectively form the amylin–Aβ plaques, promoting the progression of AD [25]. Tau protein is located in the brain cells (neurons), particularly in the hippocampus and cortex region which plays a role in regulating the assembly and maintenance of structural stability of microtubules [21]. The hyperphosphorylation of tau protein leads to disruption in the neuronal network leading to neurodegeneration that would provide bridge between diabetes mellitus with AD. Therefore, the role of Aβ formation is a primary cause of AD that plays a major role in connecting diabetes mellitus and AD respectively.

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction

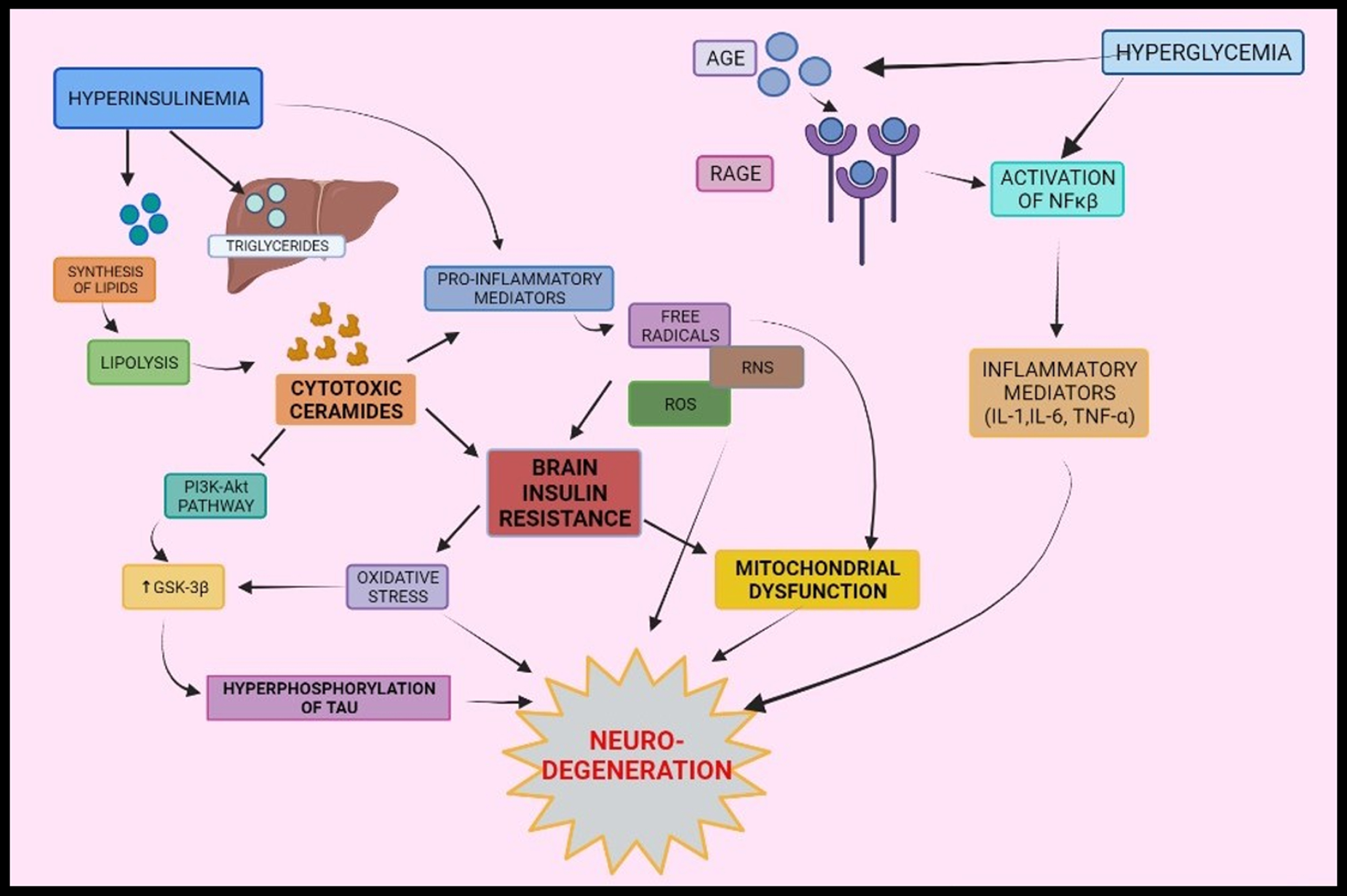

Insulin resistance causes excessive oxidative stress mainly via mitochondrial dysfunction, and DNA damage. Hyperinsulinemia occurs due to insulin resistance stimulates the synthesis of lipids and promotes the storage of triglycerides in the liver. Insulin resistance enhances lipolysis which generates toxic lipids like ceramides which impairs insulin signaling and mitochondrial function. Cytotoxic ceramides activate pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α and inhibit insulin signaling through the PI3 kinase-Akt axis. Examples of neurotoxic lipids include ceramides and sphingosines which can readily cross the BBB and resulted into neurodegeneration by precipitating a series of steps leading to brain insulin resistance. Additionally, increased expression of free radicals, NOS and NOX, are responsible for brain insulin resistance [26]. Brain insulin resistance promotes oxidative stress mainly via generation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), DNA damage, and impairment of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria [27]. Due to excessive oxidative stress, the GSK-3β pathway is also activated which amplifies hyperphosphorylation of tau protein [15].

Mitochondria are essential for neuronal function because a limited breakdown of glucose makes them highly dependent on ATP by oxidative phosphorylation producing a high amount of intrinsic toxic free radicals including hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl (HO– and superoxide O2–) which are the products of normal cellular respiration. Inhibition of electron transport chain may lead to the accumulation of electrons in complex-1 and coenzyme-Q process wherein they would be captured up by molecular O2 to give O2–. Mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase detoxifies this O2– radical to release H2O2 which is further converted by glutathione peroxidase into H2O. If the amounts of antioxidants in the mitochondria are less, the amount of free radical species produced during neuronal injury would be neutralized less which follows excessive oxidative burst and progression towards neuronal damage.

Further, an alteration in ROS and anti-oxidant levels disrupt the defensive mechanism that may lead to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Calcium-related mitochondrial dysfunction leads to overstimulation of excitatory NMDA receptors by Aβ oligomers and contributes to excessive ROS production. Moreover, NMDA receptor dysregulation seems to play a role in mitochondrial stress associated oxidative burst. Also, mitochondrial dysfunction and increased ROS production activates the JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) pathway and together promote insulin resistance [28].

Since mitochondria provide 90% of the ATP adequate for the normal functioning of neurons, neural degeneration and loss of metabolic control occur due to its dysfunction. Mitochondria also maintain cellular Ca++ homeostasis, requires for normal neuronal function. Further, it has been shown that excessive Ca++ into mitochondria leads to excessive generation of ROS/RNS which dampen the process of ATP generation and induce mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT). The sudden increase of inner mitochondrial permeability to solutes of less than 1500 dalton molecular masses is known as the MPT. MPT results into mitochondrial swelling and forms pro-apoptotic proteins which subsequently dephosphorylate insulin signaling serine-threonine protein kinase pathway and B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2) associated pathway of cell death [29]. In T2DM, dephosphorylated Bcl-2 agonist of cell death (BAD) upregulates apoptosis and causes cell death. Similarly, in AD dephosphorylated BAD protein causes mitochondrial dysfunction which results into apoptosis through its regulator Bcl-2 mediated proteins such as Caspase-3,8 (CASP-3,8), Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (PIN1), tumor suppressor p53-binding protein 2 (TP53BP2), Integral Membrane Protein 2B (ITM2B) and results in AβPP formation [16]. Overproduction of ROS has also been observed due to an oxidative change in nucleic acids, lipids, and mitochondrial proteins which triggers cells to form Aβ and undergo tau protein hyperphosphorylation and further results in neurofibrillary tangle formation [13].

2.4Advanced lipid peroxidation products

Fig. 2

Interrelationship between type-2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease via oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation: Peripheral insulin levels regulate synthesis and breakdown of lipids. Inflammatory mediators are formed by various pathways- activation of NF-κ β via binding of AGE to its receptors, cytotoxic ceramides formed as a result of lipolysis and peripheral insulin levels. Formations of inflammatory mediators elicit a series of responses that leads to brain insulin resistance and oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction and results into neurodegeneration. AGE, Advanced glycated end products; RAGE, Receptors of AGE; NF-κ β, Nuclear factor kappa β.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, are present in large amounts in the cerebral cortex of the brain. Lipid peroxidation of PUFAs, stimulated by ROS, results in the formation of several reactive α, β-unsaturated aldehydes, among which 4- hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal (HNE), 4-oxo-trans-2-nonenal (4-ONE), acrolein, and 4-oxo-trans-2-hexenal are specifically recognized as potent neurotoxic agents. These compounds undergo a chemical reaction with amino groups of protein that results in protein inactivation due to crosslinking. They mainly undergo Michael’s reaction with sulfhydryl groups of the cysteine and other nucleic acid bases of protein very easily forming adducts, which leads to DNA damage due to crosslinking. An example of these highly neurotoxic lipid peroxidation products is HNE, which is highly recognized and reacts with the microtubule network of the cell. 4-ONE is specifically more reactive and toxic than HNE. Reduced glutathione (GSH) contains sulfhydryl groups that competitively react with proteins and thus attenuate the damage caused by HNE and 4-ONE [30]. GSH is derived from cysteine, glutamate, and glycine. A deficiency of these amino acids has been shown by diabetic patients due to impaired various protein turnover and their deficiency in the diet leading to decreased glutathione synthesis [31]. GSH interacts with free radicals and forms oxidized glutathione (GSSG) in presence of enzyme glutathione peroxidase, which again gets catalyzed to glutathione by glutathione reductase and forms two molecules of GSH. This conversion helps to detoxify H2O2 to H2O; however, reduced level of glutathione has been found in diabetes and AD conditions therefore GSH does not detoxify free radicals and lipid peroxidation products and subsequently the ratio of GSSG/GSH is increased [32]. Due to these, GSH is considered as a useful biomarker for the progression of AD in T2DM patients. Further, elevated HNE concentrations correspond with upregulation of receptor tyrosine kinases and nuclear factor-κ β (NF- κ β) are also considered as suggestive biomarkers during disease progression. HNE and other pro-oxidant molecules may also responsible for Aβ protein induced oxidative stress as a result of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by HNE [30]. These activities of advanced lipid peroxidation products could contribute to linking T2DM and AD.

Immuno-inflammation

Excess immune system activation had been found to play a critical pathogenic role in T2DM and AD axis by releasing certain pro-inflammatory mediators [33]. Patel and Santani (2009) reported activation of NF-κβ was induced by hyperglycemia and binding of AGE products with its receptors. They demonstrated by conduction of several studies which showed that NF-κβ plays a role in the causality of brain inflammation during diabetes progression [34]. NF-κβ families are transcription factors containing regions for DNA binding. They exist in the form of dimers in the cytoplasm which are bound by Iκβ inhibitory proteins. When NF-κβ is activated in hyperglycemic conditions, it activates the Iκβ kinase complex which phosphorylates Iκβ and causes ubiquitination and degradation of the NF-κβ pathway. This degradation of Iκβ reveals DNA binding domain along with the nuclear localization sequence of NF-κβ which grants its translocation to the nucleus and induces transcription of genes mediating apoptosis, inflammation, proliferation, etc. thereby leading to inflammatory responses. Activated NF-κβ could cause the production of cytotoxic products that promote inflammation and oxidative stress thereby increasing apoptosis and ultimately resulting in cell death [35]. This phenomenon of IKKβ/NF-κβ induced inflammation occurs in the CNS, the hypothalamus in particular which may cause insulin resistance [36]. Additionally, NF-κβ also upregulates expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 which are responsible for development of insulin resistance through serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) [34]. T2DM is mainly characterized by elevations in C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, and TNF-α [37, 38]. In AD, extracellular Aβ-protein deposits are known to occur that lead to increase in expression of inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines and complementary system that causes neuronal damage and resulted into neurodegeneration [20]. TNF-α is the most important proinflammatory cytokine regulating inflammatory response that consists of two receptors subtypes: TNF-R1 which has been reported to increase in AD as it activates NF-κβ, mediates apoptosis, etc., on the contrary TNF-R2 is decreased as it provides neuroprotection in AD [39, 40]. As discussed earlier that when AGE products bind to their receptors, they catalyze the activation of NF-κβ thereby, modulation of inflammatory responses and BBB integrity which may progress to AD during metabolic condition of diabetes. These inflammatory mediators (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α) can cross the disrupted BBB thereby entering the brain and leading to synaptic abnormalities, neuro-insulin resistance, neuronal damage, and ultimately neurodegeneration and/or neuronal loss [31, 41].

Advanced glycation end-products

AGE products are a heterogeneous group of molecules formed by non-enzymatic glycation between Aβ and tau protein [20]. AGE products are the end products of the Maillard reaction and are also formed by ROS-mediated glycoxidation. Chronic hyperglycemia and oxidative stress synergistically increase protein glycation and enhance the formation of AGEs [2]. Receptors for AGE (RAGE) are found in neuron-derived exosomes that act as binding sites for AGE [42]. RAGE, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is expressed in multiple cell types including endothelial cells, mononuclear phagocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, neurons and microglia [17]. The formation of AGE may contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases by increased free radical activity, decreased ligand binding, modified protein half-life, and altered immunogenicity. The study performed by Chou et al. (2019) demonstrated involvement of AGE products in pathogenesis of AD/T2DM axis [43]. AGE products modification accelerates the aggregation of soluble Aβ and induces tau hyperphosphorylation which leads to facilitated development of neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques [2], which further leads to the modification of functionally important proteins like tubulin and Na+/K+ ATPase pump and hence affects neuronal function [44]. Examples of AGE products include majorly methylglyoxal which forms an adduct with DNA nucleic acid and base. Pentosidine and N ɛ-carboxymethyl-lysine are common in both diabetes and AD pathologies and could function as an important biomarker for disease progression [30].

Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase

AChE and BChE enzymes are a part of the esterase family. In AD, AChE levels tend to decrease in the brain and to compensate for this decrease, BChE levels may increase which hydrolyzes abundant acetylcholine in the brain. Hence, alteration in the ratio of AChE and BChE causes cholinergic deficit. In diabetes mellitus, AChE levels increase which leads to a acetylcholine deficit in brain [45]. Therefore, in diabetes mellitus increase in AChE levels with associated acetylcholine deficiency would increase Aβ peptide levels, which ultimately enhances plaque formation in the brain causing AD [46]. In addition to amyloid deposition, a decrease in acetylcholine levels also resulted into elevated levels of inflammatory mediators like IL-1β and TNF-α [47].

Apolipoprotein E

ApoE is a brain-specific lipoprotein secreted by astrocytes that metabolize and redistribute cholesterol as well as lipoproteins for maintaining the integrity of neuronal membranes. ApoE does not cross the BBB but has direct effects on the brain by modifying the transport of Aβ and lipid cholesterol metabolism [48, 49]. Increased cholesterol metabolism eventually increases caveolae number, which are lipid rafts enriched with cholesterol made up of proteins- caveolin-I and caveolin-II. Caveolin-I is located in pancreatic β-cells, mainly responsible for insulin signaling [50]. ApoE contains three isoforms, ApoE ɛ2, ApoE ɛ3, and ApoE ɛ4. A study conducted by Irie et al. (2008) suggested that synergistic action of diabetes and ApoE ɛ4 increases the risk of dementia for AD patients [51]. The reason for development of dementia was involvement of ApoE ɛ4 in the formation of caveolae which modulates insulin signaling by altering the interaction of insulin with its receptor leading to insulin resistance which ultimately results into impaired insulin signaling, mitochondrial respiration, and glycolysis. Along with this, increased caveolae formation also increases the deposition of Aβ fibrils [50]. Therefore, diabetes and ApoE enhance the risk of AD by Aβ aggregation, neuritic plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles [51].

SUMMARY

T2DM and AD are very closely linked to each other. This bridging is due to several pathological phenomenons involved during progression of diseases. Both T2DM and AD conditions may lead to variety of complications and activation of the immune system. Diabetes is characterized by hyperglycemia which elevates the level of insulin as impairment in its signaling can occur, leading to insulin resistance. Hyperinsulinemia also increases amyloid formation and tau protein hyperphosphorylation, leads to neuronal network disruption, neurodegeneration and finally death. Along with these pathologies, certain other mechanisms support the link between T2DM and AD, which include the release of pro-inflammatory mediators by NF-κ β activation, AGE formation, abnormal lipid peroxidation on neuronal membrane, alteration in level of AChE and BChE. These can aggravate Aβ production, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neurofibrillary tangle formation and finally loss of neuronal functions which subsequently lead to AD during diabetic condition. The authors would like to thank Dr. Gaurang B. Shah and L.M. College of Pharmacy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Gaurang B. Shah and L.M. College of Pharmacy.

FUNDING

The authors have no funding to report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

[1] | Defronzo RA ((2009) ) From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: A new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 58: , 773–795. |

[2] | Yang Y , Song W ((2013) ) Molecular links between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes mellitus. Neuroscience 250: , 140–150. |

[3] | Wang KC , Woung LC , Tsai MT , Liu CC , Su YH , Li CY ((2012) ) Risk of Alzheimer’s disease in relation to diabetes: A population-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology 38: , 237–244. |

[4] | Arvanitakis Z , Wilson RS , Bienias JL , Evans DA , Bennett DA ((2004) ) Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer disease and decline in cognitive function. Arch Neurol 61: , 661–666. |

[5] | Kroner Z ((2009) ) The relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes: Type 3 diabetes? Altern Med Rev 14: , 373–379. |

[6] | De La Monte SM , Wands JR ((2008) ) Alzheimer’s disease is type 3 diabetes-evidence reviewed. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2: , 1101–1113. |

[7] | Sebastião I , Candeias E , Santos MS , de Oliveira CR , Moreira PI , Duarte AI ((2014) ) Insulin as a bridge between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease - how anti-diabetics could be a solution for dementia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5: , 110. |

[8] | Xu WL , Von Strauss E , Qiu CX , Winblad B , Fratiglioni L ((2009) ) Uncontrolled diabetes increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A population-based cohort study. Diabetologia 52: , 1031–1039. |

[9] | Blázquez E , Velázquez E , Hurtado-Carneiro V , Ruiz-Albusac JM ((2014) ) Insulin in the brain: Its pathophysiological implications for states related with central insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and alzheimer’s disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5: , 161. |

[10] | Haghir H ((2016) ) Cognitive function in offspring of mothers with gestational diabetes–the role of insulin receptor. MOJ Anat Physiol 2: , 182–185. |

[11] | Luchsinger JA , Tang MX , Shea S , Mayeux R ((2004) ) Hyperinsulinemia and risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 63: , 1187–1192. |

[12] | Pivovarova O , Höhn A , Grune T , Pfeiffer AFH , Rudovich N ((2016) ) Insulin-degrading enzyme: New therapeutic target for diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease? . Ann Med 48: , 614–624. |

[13] | Akter K , Lanza EA , Martin SA , Myronyuk N , Rua M , Raffa RB ((2011) ) Diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease: Shared pathology and treatment? Br J Clin Pharmacol 71: , 365–376. |

[14] | De Meyts P (2016) The insulin receptor and its signal transduction network. In Endotext, Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de HerderWW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hershman JM, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, Morley JE, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, eds. MDText.com, Inc., South Dartmouth, MA, pp. 1–42. |

[15] | De La Monte SM ((2012) ) Contributions of brain insulin resistance and deficiency in amyloid-related neurodegeneration in alzheimers disease. Drugs 72: , 49–66. |

[16] | Mittal K , Mani RJ , Katare DP ((2016) ) Type 3 diabetes: Cross talk between differentially regulated proteins of type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 6: , 25589. |

[17] | Zhao WQ , Townsend M ((2009) ) Insulin resistance and amyloidogenesis as common molecular foundation for type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1792: , 482–496. |

[18] | Rorbach-Dolata A , Piwowar A ((2019) ) Neurometabolic evidence supporting the hypothesis of increased incidence of type 3 diabetes mellitus in the 21st century. Biomed Res Int 2019: , 1435276. |

[19] | Chatterjee S , Ambegaokar SS , Jackson GR , Mudher A ((2019) ) Insulin-mediated changes in tau hyperphosphorylation and autophagy in a Drosophila model of tauopathy and neuroblastoma cells. Front Neurosci 13: , 801. |

[20] | Granic I , Dolga AM , Nijholt IM , Van Dijk G , Eisel ULM ((2009) ) Inflammation and NF-κB in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. J Alzheimers Dis 16: , 809–821. |

[21] | Zhang YW , Thompson R , Zhang H , Xu H ((2011) ) APP processing in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Brain 4: , 3. |

[22] | Tan JZA , Gleeson PA ((2019) ) The role of membrane trafficking in the processing of amyloid precursor protein and production of amyloid peptides in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1861: , 697–712. |

[23] | Raimundo AF , Ferreira S , Martins IC , Menezes R ((2020) ) Islet amyloid polypeptide: A partner in crime with Aβ in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Neurosci 13: , 35. |

[24] | Arya S , Claud SL , Cantrell KL , Bowers MT ((2019) ) Catalytic prion-like cross-talk between a key Alzheimer’s disease tau-fragment R3 and the type 2 diabetes peptide IAPP. ACS Chem Neurosci 10: , 4757–4765. |

[25] | Baram M , Atsmon-Raz Y , Ma B , Nussinov R , Miller Y ((2016) ) Amylin-Aβ oligomers at atomic resolution using molecular dynamics simulations: A link between Type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Phys Chem Chem Phys 18: , 2330–2338. |

[26] | Diehl T , Mullins R , Kapogiannis D ((2017) ) Insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Res 183: , 26–40. |

[27] | Butterfield DA , Di Domenico F , Barone E ((2014) ) Elevated risk of type 2 diabetes for development of Alzheimer disease: A key role for oxidative stress in brain. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842: , 1693–1706. |

[28] | De Felice FG , Ferreira ST ((2014) ) Inflammation, defective insulin signaling, and mitochondrial dysfunction as common molecular denominators connecting type 2 diabetes to Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 63: , 2262–2272. |

[29] | Moreira PI , Santos MS , Seiça R , Oliveira CR ((2007) ) Brain mitochondrial dysfunction as a link between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. J Neurol Sci 257: , 206–214. |

[30] | Reddy VP , Zhu X , Perry G , Smith MA ((2009) ) Oxidative stress in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 16: , 763–774. |

[31] | Rosales-Corral S , Tan DX , Manchester L , Reiter RJ ((2015) ) Diabetes and alzheimer disease, two overlapping pathologies with the same background: Oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015: , 985845. |

[32] | Pocernich CB , Butterfield DA ((2012) ) Elevation of glutathione as a therapeutic strategy in Alzheimer disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1822: , 625–630. |

[33] | Chatterjee S , Mudher A ((2018) ) Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes: A critical assessment of the shared pathological traits. Front Neurosci 12: , 383. |

[34] | Patel S , Santani D ((2009) ) Role of NF-κB in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its associated complications. Pharmacol Rep 61: , 595–603. |

[35] | Muriach M , Flores-Bellver M , Romero FJ , Barcia JM ((2014) ) Diabetes and the brain: Oxidative stress, inflammation, and autophagy. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014: , 102158. |

[36] | Cai D , Liu T ((2012) ) Inflammatory cause of metabolic syndrome via brain stress and NF-κB. Aging (Albany NY) 4: , 98–115. |

[37] | Haan MN ((2006) ) Therapy insight: Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2: , 159–166. |

[38] | Vagelatos NT , Eslick GD ((2013) ) Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: The confounders, interactions, and neuropathology associated with this relationship. Epidemiol Rev 35: , 152–160. |

[39] | Yang S , Wang J , Brand DD , Zheng SG ((2018) ) Role of TNF-TNF receptor 2 signal in regulatory T cells and its therapeutic implications. Front Immunol 9: , 784. |

[40] | DecourtB, LahiriDK, SabbaghMN ((2011) ) Targeting tumor necrosis factor alpha for Alzheimer’s disease. Physiol Behav 176: , 139–148. |

[41] | Ferreira LSS , Fernandes CS , Vieira MNN , De Felice FG ((2018) ) Insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci 12: , 830. |

[42] | Jash K , Gondaliya P , Kirave P , Kulkarni B , Sunkaria A , Kalia K ((2020) ) Cognitive dysfunction: A growing link between diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Dev Res 81: , 144–164. |

[43] | Chou PS , Wu MN , Yang CC , Shen CT , Yang YH ((2019) ) Effect of advanced glycation end products on the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 72: , 191–197. |

[44] | Biessels GJ , Van der Heide LP , Kamal A , Bleys RLAW , Gispen WH ((2002) ) Ageing and diabetes: Implications for brain function. Eur J Pharmacol 441: , 1–14. |

[45] | MushtaqG, GreigNH, KhanJA, KamalMA ((2014) ) Status of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 13: , 1432–1439. |

[46] | Rees TM , Brimijoin S ((2003) ) The role of acetylcholinesterase in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Today 39: , 75. |

[47] | Rao AA , Sridhar GR , Das UN ((2007) ) Elevated butyrylcholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase may predict the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. Med Hypotheses 69: , 1272–1276. |

[48] | Chen Y , Strickland MR , Soranno A , Holtzman DM ((2021) ) Apolipoprotein E: Structural insights and links to Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Neuron 109: , 205–221. |

[49] | Rhea EM , Raber J , Banks WA ((2020) ) ApoE and cerebral insulin:Trafficking, receptors, and resistance. Neurobiol Dis 137: , 104755. |

[50] | Sima AAF , Li Z ((2006) ) Diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease - is there a connection? Rev Diabet Stud 3: , 161–161. |

[51] | Irie F , Fitzpatrick AL , Lopez OL , Kuller LH , Peila R , Newman AB , Launer LJ ((2008) ) Enhanced risk for Alzheimer disease in persons with type 2 diabetes and APOE ɛ4. Arch Neurol 65: , 89–94. |