Abstract

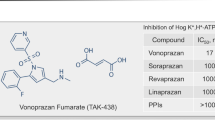

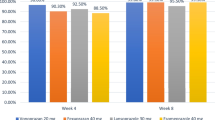

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) [omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and esomeprazole] are widely utilised for the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, as well as other acid-related disorders. All PPIs suppress gastric acid secretion by blocking the gastric acid pump, H+/K+-adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase), but the physicochemical properties of these drugs result in variations in the degree of acid suppression, as well as the speed of onset of acid inhibition. Such differences may impact on the clinical performance of PPIs, and this manuscript discusses data that may help clinicians choose between the available PPIs for specific clinical situations and indications. The characteristics of PPIs that have been developed subsequent to omeprazole offer several advantages over this prototype PPI, particularly with respect to the onset of acid suppression and reduced potential for inter-individual pharmacokinetic variation and drug interactions. Newer agents inhibit H+/K+-ATPase more rapidly than omeprazole and emerging clinical data support potential clinical benefits resulting from this pharmacological property.

Although key pharmacokinetic parameters (time to maximum plasma concentration and elimination half-life) do not differ significantly among PPIs, differences in the hepatic metabolism of these drugs can produce inter-patient variability in acid suppression, in the potential for pharmacokinetic drug interactions and, quite possibly, in clinical efficacy. All PPIs undergo significant hepatic metabolism. Because there is no direct toxicity from PPIs, there is minimal risk from the administration of any of them — even to patients with significant renal or hepatic impairment. However, there are significant genetic polymorphisms for one of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes involved in PPI metabolism (CYP2C19), and this polymorphism has been shown to substantially increase plasma levels of omeprazole, lansoprazole and pantoprazole, but not those of rabeprazole. Hepatic metabolism is also a key determinant of the potential for a given drug to be involved in clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions. Omeprazole has the highest risk for such interactions among PPIs, and rabeprazole and pantoprazole appear to have the lowest risk.

Thus, whereas all PPIs have been shown to be generally effective and safely used for the treatment of acid-mediated disorders, there are chemical, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic differences among these drugs that may make certain ones more, or less, suitable for treating different patient subgroups. Of course, the absolute magnitude of risk from any PPI in terms of drug-drug interactions is probably low — excepting interactions occurring as class effects related to acid suppression (e.g. increased digoxin absorption or inability to absorb ketoconazole).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sonnenberg A, El-Serag HB. Clinical epidemiology and natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Yale J Biol Med 1999 Mar–Jun; 72: 81–92

Jones R, Bytzer P. Review article: acid suppression in the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: an appraisal of treatment options in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001 Jun; 15: 765–72

Colin-Jones DG. The role and limitations of H2-receptor antagonists in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1995; 9 Suppl. 1: 9–14

DeVault KR. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: extraesophageal manifestations and therapy. Semin Gastrointest Dis 2001 Jan; 12: 46–51

Salas M, Ward A, Caro J. Are proton pump inhibitors the first choice for acute treatment of gastric ulcers?: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Gastroenterol 2002 Jul 15; 2: 17–23

Barrison AF, Jarboe LA, Weinberg BM, et al. Patterns of proton pump inhibitor use in clinical practice. Am J Med 2001 Oct 15; 111: 469–73

Robinson M. Dyspepsia: challenges in diagnosis and selection of treatment. Clin Ther 2001 Aug; 23: 1130–44

Sachs G. Improving on PPI-based therapy of GORD. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001 May; 13 Suppl. 1: S35–41

Besancon M, Simon A, Sachs G, et al. Sites of reaction of the gastric H,K-ATPase with extracytoplasmic thiol reagents. J Biol Chem 1997 Sep 5; 272: 22438–46

Kromer W. Relative efficacies of gastric proton-pump inhibitors on a milligram basis: desired and undesired SH reactions. Impact of chirality. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 2001; 234: 3–9

Kromer W, Kruger U, Huber R, et al. Differences in pH-dependent activation rates of substituted benzimidazoles and biological in vitro correlates. Pharmacology 1998 Feb; 56: 57–70

Pantoflickova D, Dorta G, Ravic M, et al. Acid inhibition on the first day of dosing: comparison of four proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003 Jun 15; 17: 1507–14

Williams MP, Sercombe J, Hamilton MI, et al. A placebo-controlled trial to assess the effects of 8 days of dosing with rabeprazole vs omeprazole on 24-h intragastric acidity and plasma gastrin concentrations in young healthy male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998 Nov; 12: 1079–89

Gardner JD, Sloan S, Barth JA. Onset, duration, and magnitude of gastric antisecretory effects of rabeprazole and omeprazole [abstract no. 125]. Am J Gastroenterol 1999 Oct; 94 Suppl.: 2608

Huang JQ, Goldwater DR, Thomson AB, et al. Acid suppression in healthy subjects following lansoprazole or pantopra-zole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002 Mar; 16: 425–33

Geus WP, Mathot RA, Mulder PG, et al. Pharmacodynamics and kinetics of omeprazole MUPS 20 mg and pantoprazole 40 mg during repeated oral administration in Helicobacter pylori-negative subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Aug; 14: 1057–64

Ehrlich A, Lucker PW, Wiedemann A, et al. Comparison of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole (40 mg) as compared to omeprazole MUPS (20 mg) after repeated oral dose administration. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 1999 Jan–Feb; 21: 47–51

Warrington S, Baisley K, Boyce M, et al. Effects of rabeprazole, 20 mg, or esomeprazole, 20 mg, on 24-h intragastric pH and serum gastrin in healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002 Jul; 16: 1301–7

Lind T, Rydberg L, Kyleback A, et al. Esomeprazole provides improved acid control vs. omeprazole in patients with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Jul; 14: 861–7

Wilder-Smith C, Claar-Nilsson C, Hasselgren G, et al. Esomeprazole 40 mg provides faster and more effective acid control than rabeprazole 20 mg in patients with symptoms of GERD [abstract no. 137]. Am J Gastroenterol 2001 Sep; 96 Suppl.: S45

Baisley KJ, Warrington SJ, Tejura B, et al. Rabeprazole 20 mg compared with esomeprazole 40 mg in the control of intragastric pH in healthy volunteers [abstract no. 229]. Gut 2002 Oct; 50 Suppl. II: A63

Scott LJ, Dunn CJ, Mallarkey G, et al. Esomeprazole: a review of its use in management of acid-related disorders. Drugs 2002 Oct; 62: 1503–38

Prakash A, Faulds D. Rabeprazole. Drugs 1998 Feb; 55: 261–7

Landes BD, Petite JP, Fluovat B. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet 1995 Jun; 28: 458–70

Huber R, Hartmann M, Bliesath H, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole in man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996 May; 34: 185–94

Barone J, Horn JR. Comparative pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Manag Care 2001; 10 Suppl.: 11–6

Touw DJ. Clinical implications of genetic polymorphisms and drug interactions mediated by cytochrome P-450 enzymes. Drug Metabol Drug Interact 1997; 14: 55–82

Ishizaki T, Horai Y. Review article: cytochrome P450 and the metabolism of proton pump inhibitors: emphasis on rabeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Aug; 13 Suppl. 3: 27–36

Andersson T, Hassan-Alin M, Hasselgren G, et al. Pharmacokinetic studies with esomeprazole, the (S)-isomer of omeprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40: 411–26

Andersson T, Röhss K, Bredberg E, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of esomeprazole, the s-isomer of omeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001 Oct; 15: 1563–9

Goldstein JA. Clinical relevance of genetic polymorphisms in the human CYP2C subfamily. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001 Oct; 52: 349–55

Sakai T, Aoyama N, Kita T, et al. CYP2C19 genotype and pharmacokinetics of three proton pump inhibitors in healthy subjects. Pharm Res 2001 Jun; 18: 721–7

Shirai N, Furuta T, Moriyama Y, et al. Effects of CYP2C19 genotypic differences in the metabolism of omeprazole and rabeprazole on intragastric pH. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001 Dec; 15: 1929–37

Furuta T, Kyoichi O, Kosuge K, et al. CYP2C19 genotype status and effect of omeprazole on intragastric pH in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999 May; 65: 552–61

Furuta T, Shirai N, Xiao F, et al. Effect of high-dose lansoprazole on intragastic pH in subjects who are homozygous extensive metabolizers of cytochrome P4502C 19. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001 Nov; 70: 484–92

Horai Y, Kimura M, Furuie H, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and kinetic disposition of rabeprazole in relation to CYP2C19 genotypes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001 Jun; 15: 793–803

Röhss K, Hasselgren G, Hedenstrom H. Effect of esomeprazole 40 mg vs omeprazole 40 mg on 24-hour intragastric pH in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 2002 May; 47: 954–8

Lin JH, Lu AY. Inhibition and induction of cytochrome P450 and the clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet 1998 Nov; 35: 361–90

Humphries TJ, Merritt GJ. Review article: drug interactions with agents used to treat acid-related diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Aug; 13 Suppl. 3: 18–26

Hansten P, Horn J. The top 100 drug interactions: a guide to patient management. Edmonds (WA): H&H Publications, 2003: 30, 121–34

Bottiger Y, Tybring G, Gotharson E. Inhibition of the sulfoxidation of omeprazole by ketoconazole in poor and extensive metabolizers of S-mephenytoin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1997 Oct; 62: 384–91

Christensen M, Tybring G, Mihara K, et al. Low daily 10 mg and 20 mg doses of fluvoxamine inhibit the metabolism of both caffeine (cytochrome P4501A2) and omeprazole (cytochrome P4502C19). Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002 Mar; 71: 141–52

Schouler L, Dumas F, Couzigou P, et al. Omeprazole-cyclosporin interaction [letter]. Am J Gastroenterol 1991 Aug; 86:1097

Marti-Masso JF, Lopez D, Munian A, et al. Ataxia following gastric bleeding due to omeprazole-benzodiazepine interaction [letter]. Ann Pharmacother 1992 Mar; 26: 429–30

Ahmad S. Omeprazole-warfarin interaction [letter]. South Med J 1991 May; 84: 674–5

AstraZeneca LP. Prilosec (omeprazole). United States prescribing information. Wilmington (DE): AstraZeneca LP, 2003

Ushiama H, Echizen H, Nachi S, et al. Dose-dependent inhibition of CYP3A4 activity by clarithromycin during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy assessed by changes in plasma lansoprazole levels and partial cortisol clearance to 6β-hydroxycortisol. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002 Jul; 72: 33–43

Homma M, Itagaki F, Yuzawa K, et al. Effects of lansoprazole and rabeprazole on tacrolimus blood concentration: case of a renal transplant recipient with CYP2C19 gene mutation. Transplantation 2002 Jan 27; 73: 303–4

Tröger U, Stötzel B, Martens-Lobenhoffer J, et al. Drug points: severe myalgia from an interaction between treatments with pantoprazole and methotrexate. BMJ 2002 Jun 22; 324: 1497

Ishizaki T, Chiba K, Manabe K, et al. Comparison of the interaction potential of a new proton pump inhibitor, E3810, versus omeprazole with diazepam in extensive and poor metabolizers of S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1995 Aug; 58: 155–64

Andersson T, Hassan-Alin M, Hasselgren G, et al. Drug interaction studies with esomeprazole, the (S)-isomer of omeprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40: 523–37

Tybring G, Bottiger Y, Widen J, et al. Enantioselective hydroxylation of omeprazole catalyzed by CYP 2C19 in Swedish white subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1997 Aug; 62: 129–37

Belpaire FM, Bogaert MG. Cytochrome P450: genetic polymorphism and drug interactions. Acta Clin Belg 1996; 51: 254–60

Yu KS, Yim DS, Cho JY, et al. Effect of omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of moclobemide according to the genetic polymorphism of CYP2C 19. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001 Apr; 69: 266–73

Furuta T, Ohashi K, Kobayashi K, et al. Effects of clarithroymycin on the metabolism of omeprazole in relation to CYP2C19 genotype status in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999 Sep; 66: 265–74

Lind T, Rydberg L, Kyleback A, et al. Esomeprazole provides improved acid control vs. omeprazole in patients with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Jul; 14: 861–7

Caro JJ, Salas M, Ward A. Healing and relapse rates in gastroesophageal reflux disease treated with the newer proton-pump inhibitors lansoprazole, rabeprazole, and pantoprazole compared with omeprazole, ranitidine, and placebo: evidence from randomized clinical trials. Clin Ther 2001 Jul; 23: 998–1017

Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2001 Mar; 96: 656–65

Kahrilas PJ, Falk GW, Johnson DA, et al. Esomeprazole improves healing and symptom resolution as compared with omeprazole in reflux oesophagitis patients: a randomized controlled trial. The Esomeprazole Study Investigators. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Oct; 14: 1249–58

AstraZeneca LP. Nexium (esomeprazole). United States prescribing information. Wilmington (DE): AstraZeneca LP, 2003

Howden C, Ballard D, Robieson W. Evidence for therapeutic equivalence of lansoprazole 30mg and esomeprazole 40mg in the treatment of erosive oesophagitis. Clin Drug Invest 2002; 22: 99–109

Castell DO, Kahrilas PJ, Richter JE, et al. Esomeprazole (40 mg) compared with lansoprazole (30 mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002 Mar; 97: 575–83

Cohen H. Peptic ulcer and Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2000 Dec; 29: 775–89

Richardson P, Hawkey CJ, Stack WA. Proton pump inhibitors: pharmacology and rationale for use in gastrointestinal disorders. Drugs 1998 Sep; 56: 307–35

Van Oijen AH, Verbeek AL, Jansen JB, et al. Review article: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection with ranitidine bismuth citrate- or proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Aug; 14: 991–9

Yeomans ND. Management of peptic ulcer disease not related to Helicobacter. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002 Apr; 17: 488–94

Graham DY, Agrawal NM, Campbell DR, et al. Ulcer prevention in long-term users of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, active- and placebo-controlled study of misoprostol vs lansoprazole. Arch Intern Med 2002 Jan 28; 162: 169–75

Agrawal NM, Campbell DR, Safdi MA, et al. Superiority of lansoprazole vs ranitidine in healing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastric ulcers: results of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter study. NSAID-Associated Gastric Ulcer Study Group. Arch Intern Med 2000 May 22; 160: 1455–61

Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM, et al. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term lowdose aspirin use. N Engl J Med 2002 Jun 27; 346: 2033–8

Chan FK, Hung LC, Suen BY, et al. Celecoxib versus diclo-fenac and omeprazole in reducing the risk of recurrent bleeding in patients with arthritis. N Engl J Med 2002 Dec 26; 347: 2104–10

Bour B, Pariente EA, Hamelin B, et al. Orally administered omeprazole versus injection therapy in the prevention of rebleeding from peptic ulcer with visible vessel: a multicenter randomized study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1993; 17: 329–33

Mohamed SA, al Karawi MA. Omeprazole versus histamine H2 receptor antagonists in the treatment of acute upper nonvariceal bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology 1996 Jul–Aug; 43: 863–5

Barnett JL, Robinson M. Optimizing acid-suppression therapy. Manag Care 2001 Oct; 10 Suppl. 10: 17–21

Smith JL, Opedun AR, Larkai E, et al. Sensitivity of the esophageal mucosa to pH in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1989 Mar; 96: 683–9

Achem SR. Endoscopy-negative gastroesophageal reflux disease: the hypersensitive esophagus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1999 Dec; 28: 893–904

Bate CM, Griffin SM, Keeling PWN, et al. Reflux symptom relief with omeprazole in patients without unequivocal oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1996 Aug; 10: 547–55

Lind T, Havelund T, Carlsson R, et al. Heartburn without oesophagitis: efficacy of omeprazole therapy and features determining therapeutic response. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997 Oct; 32: 974–9

Venables TL, Newland RD, Patel AC, et al. Maintenance treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a placebo-controlled evaluation of 10 milligrams omeprazole once daily in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997 Jul; 32: 627–32

Richter JE, Kovacs TO, Greski-Rose PA, et al. Lansoprazole in the treatment of heartburn in patients without erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Jun; 13: 795–804

Miner Jr P, Orr W, Filippone J, et al. Rabeprazole in nonerosive gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2002 Jun; 97: 1332–9

DeVault KR, Castell DO, The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999 Jun; 94: 1434–42

El-Serag HB, Aguirre T, Kubeler M, et al. The length of newly diagnosed Barrett’s esophagus and prior use of acid suppressive therapy [abstract no. 14]. Am J Gastroenterol 2003 Sep; 98 (9 Suppl.): S5

Aguirre T, El-Serag H, Davis S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the incidence of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus [abstract no. 66]. Am J Gastroenterol 2003 Sep; 98 (9 Suppl.): S23

Bank S, Singh R, Indaram A, et al. Maintenance proton pump inhibitor therapy decreases the incidence of esophageal cancer and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus and chronic heartburn [abstract no. 88]. Am J Gastroenterol 2003 Sep; 98 (9 Suppl.): S31

Koop H. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy 2002 Feb; 34: 97–103

Fass R, Ofman JJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: should we adopt a new conceptual framework? Am J Gastroenterol 2002 Aug; 97: 1901–9

Hungin AP, Rubin GP, O’Flanagan H. Long-term prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1999 Jun; 49: 451–3

Hungin AP, Rubin G, O’Flanagan H. Factors influencing compliance in long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1999 Jun; 49: 463–4

Barnett JL, Robinson M. Optimizing acid-suppression therapy. Manag Care 2001 Oct; 10 Suppl.: 17–21

Bardhan KD, Müller-LissnerS,Bigard MA, et al. Symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: double blind controlled study of intermittent treatment with omeprazole or ranitidine. BMJ 1999 Feb 20; 318: 502–7

Lind T, Havelund T, Lundell L, et al. On demand therapy with omeprazole for the long-term management of patients with heartburn without oesophagitis: a placebo-controlled randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Jul; 13: 907–14

Gerson LB, Robbins AS, Garber A, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of prescribing strategies in the management of gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Feb; 95: 395–407

Talley NJ, Lauritsen K, Tunturi-Hihnala H, et al. Esomeprazole 20 mg maintains symptom control in endoscopy-negative gastro-oesopheageal reflux disease: a controlled trial of ‘on-demand’ therapy for 6 months. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001 Mar; 15: 347–54

Johnsson F, Moum R, Vilien O, et al. On-demand treatment in patients with oesophagitis and reflux symptoms: comparison of lansoprazole and omeprazole. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002 Jun; 37: 642–7

Talley NJ, Venables TL, Green JR, et al. Esomeprazole 40 mg and 20 mg is efficacious in the long-term management of patients with endoscopy-negative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a placebo-controlled trial of on-demand therapy for 6 months. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002 Aug; 14: 857–63

Byzter P, Blum AL, de Herdt D. Fast and complete control of heartburn in on-demand rabeprazole (RAB) maintenance therapy in patients with nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) [abstract no. 1596]. Gastroenterology 2003; 124 Suppl. 1: A228

Acknowledgements

Recent substantial research support for the Oklahoma Foundation for Digestive Research has come from AstraZeneca, TAP Pharmaceuticals, Eisai Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica Inc., Wyeth, Novartis and Pfizer. Dr Horn has spoken and consulted for Pfizer, Janssen Pharmaceutica Inc. and TAP Pharmaceuticals. The preparation of this manuscript involved editorial assistance from International Meetings & Science Inc. The authors take full responsibility for all manuscript contents.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robinson, M., Horn, J. Clinical Pharmacology of Proton Pump Inhibitors. Drugs 63, 2739–2754 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200363240-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200363240-00004