Abstract

Cocaine abuse is a serious health problem in many areas of the world, yet there are no proven effective medications for the treatment of cocaine dependence.

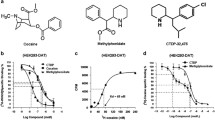

Preclinical studies suggest that the reinforcing effect of cocaine that promotes its abuse is mediated by blockade of the presynaptic dopamine transporter. This results in increased dopamine activity in the mesolimbic or meso-accumbens dopamine reward system of brain. Development of new medications to treat cocaine dependence has focused on manipulation of this dopamine system, either by direct action on dopamine binding sites (transporter or receptors) or indirectly by affecting other neurotransmitter systems that modulate the dopamine system. In principle, a medication could act via one of three mechanisms: (i) as a substitute for cocaine by producing similar dopamine effects; (ii) as a cocaine antagonist by blocking the binding of cocaine to the dopamine transporter; or (iii) as a modulator of cocaine effects by acting at other than the cocaine binding site.

The US National Institute on Drug Abuse has a Clinical Research Efficacy Screening Trial (CREST) programme to rapidly screen existing medications. CREST identified four medications warranting phase II controlled clinical trials: cabergoline, reserpine, sertraline and tiagabine. In addition, disulfiram and selegiline (deprenyl) have been effective and well tolerated in phase II trials. However, selegiline was found ineffective in a recent phase III trial.

Promising existing medications probably act via the first or third aforementioned mechanisms. Sustained-release formulations of stimulants such as methyl-phenidate and amfetamine (amphetamine) have shown promise in a stimulant substitution approach. Disulfiram and selegiline increase brain dopamine concentrations by inhibition of dopamine-catabolising enzymes (dopamine-β-hydroxylase and monoamine oxidase B, respectively). Cabergoline is a direct dopamine receptor agonist, while reserpine depletes presynaptic stores of dopamine (as well as norepinephrine and serotonin). Sertraline, baclofen and vigabatrin indirectly reduce dopamine activity by increasing activity of neurotransmitters (serotonin and GABA) that inhibit dopamine activity.

Promising new medications act via the second or third aforementioned mechanisms. Vanoxerine is a long-acting inhibitor of the dopamine transporter which blocks cocaine binding and reduces cocaine self-administration in animals. Two dopamine receptor ligands that reduce cocaine self-administration in animals are also undergoing phase I human safety trials. Adrogolide is a selective dopamine D1 receptor agonist; BP 897 is a D3 receptor partial agonist.

A pharmacokinetic approach to treatment would block the entry of cocaine into the brain or enhance its catabolism so that less cocaine reached its site of action. This is being explored in animals using the natural cocaine-metabolising enzyme butyrylcholinesterase (or recombinant versions with enhanced capabilities), catalytic antibodies, and passive or active immunisation to produce anti-cocaine binding antibodies. A recent phase I trial of a ‘cocaine vaccine’ found it to be well tolerated and producing detectable levels of anti-cocaine antibodies for up to 9 months after immunisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

United Nations Drug Control Program. Global illicit drug trends 2002. New York: United Nations Drug Control Program, 2002

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on drug abuse. Volume I: summary of national findings. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002. DHHS Publication No. SMA 01-3549, NHSDA Series: H-13

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Emergency department trends from the drug abuse warning network, final estimates 1994–2001. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002 Aug. DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3635, DAWN Series D-21

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 1992–2000. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002 Dec. DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3727, DASIS Series S-17

Gorelick DA. Pharmacological treatment of cocaine addiction. Einstein Q J Biol Med 1999; 16: 61–9

Gorelick DA. Pharmacologic interventions for cocaine, crack, and other stimulant addiction. In: Graham AW, Schultz TK, Mayo-Smith M, et al., editors. Principles of addiction medicine. 3rd ed. Chevy Chase (MD): American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2003: 89–111

de Lima MS, Soares BGO, Reisser AAP, et al. Pharmacological treatment of cocaine dependence: a systematic review. Addiction 2002; 97: 931–49

Lewin Group. Market barriers to the development of pharmaco-therapies for the treatment of cocaine abuse and addiction: final report. Fairfax (VA): Lewin Group; 1997 Sep12. Contract HHS-100-96-0011

Gorelick DA. The rate hypothesis and agonist substitution approaches to cocaine abuse treatment. Adv Pharmacol 1998; 42: 995–7

Dackis CA, O’Brien CP. Cocaine dependence: a disease of the brain’s reward centers. J Subst Abuse Treat 2001; 21: 111–7

Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD. Behavioral effects of cocaine and dopaminergic strategies for preclinical medication development. Psychopharmacology 2002; 163: 265–82

Wise RA, Gardner EL. Animal models of addiction. In: Charney DS, Nestler EJ, editors. Neurobiology of mental illness. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press 2004: 683–97

Gardner EL. What we have learned about addiction from animal models of drug self-administration. Am J Addict 2000; 9: 285–313

Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, et al. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology 2003; 168: 3–20

Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference paradigm: a comprehensive review of drug effects, recent progress and new issues. Prog Neurobiol 1998; 56: 613–72

Colpaert FC. Drug discrimination in neurobiology. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1999; 64: 337–45

Wise RA. Addictive drugs and brain stimulation reward. Annu Rev Neurosci 1996; 19: 319–40

Wolf ME. The role of excitatory amino acids in behavioral sensitization to psychomotor stimulants. Prog Neurobiol 1998; 54: 679–720

Vanderschuren LJMJ, Kalivas PW. Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic signaling in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization. Psychopharmacology 2000; 151: 99–120

Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction 2001; 96: 103–14

Wise RA, Gardner EL. Functional anatomy of substance-related disorders. In: D’haenen H, den Boer JA, Willner P, editors. Biological psychiatry. New York: Wiley, 2002: 509–22

Howell LL, Wilcox KM. Functional imaging and neurochemical correlates of stimulant self-administration in primates. Psychopharmacology 2002; 163: 352–61

Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fischman MW, et al. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature 1997; 386: 827–30

Rothman RB, Glowa JR. A review of the effects of dopaminergic agents on humans, animals, and drug-seeking behavior, and its implications for medication development: focus on GBR-12909. Mol Neurobiol 1995; 11: 1–19

Schweri MM, Deutsch HM, Massey AT, et al. Biochemical and behavioral characterization of novel methylphenidate analogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 301: 527–35

Carroll FI. 2002 Medicinal chemistry division award address: monoamine transporters and opioid receptors: targets for addiction therapy. J Med Chem 2003; 46: 1775–94

Madras BK, Spealman RD, Fahey MA, et al. Cocaine receptors labeled by [3H]2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(fluorophenyl)tropane. Mol Pharmacol 1989; 36: 518–24

Woolverton WL, Rowlett JK, Wilcox KM, et al. 3′- and 4′-chloro-substituted analogs of benztropine: intravenous self-administration and in vitro radioligand binding studies in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 2000; 147: 426–35

Hsin LW, Dersch CM, Baumann MH, et al. Development of long-acting dopamine transporter ligands as potential cocaine-abuse therapeutic agents: chiral hydroxyl-containing derivatives of l-[2-[bis (4-fluorophenyl)methoxy]ethyl]-4-(3-phenylpropyl)piperazine and l-[2-(diphenylmethoxy)ethyl]-4-(3-phenylpropyl)piperazine. J Med Chem 2002; 45: 1321–9

Froimowitz M, Wu K-M, Moussa A, et al. Slow-onset, long-duration 3-(3′,4′-dichlorophenyl)-l-indanamine monoamine reuptake blockers as potential medications to treat cocaine abuse. J Med Chem 2000; 43: 4981–92

Volkow ND, Ding Y-S, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52: 456–63

Sizemore GM, Davies HM, Martin TJ, et al. Effects of 2beta-propanoyl-3beta-(4-tolyl)-tropane (PIT) on the self-administration of cocaine, heroin, and cocaine/heroin combinations in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004; 73: 259–65

Hemby SE, Co C, Reboussin D, et al. Comparison of a novel tropane analog of cocaine, 2 beta-propanoyl-3 beta-(4-tolyl) tropane with cocaine HCl in rats: nucleus accumbens extracellular dopamine concentration and motor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995; 273: 656–66

Roberts DC, Jungersmith KR, Phelan R, et al. Effect of HD-23, a potent long acting cocaine-analog, on cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003; 167(4): 386–92

Lile JA, Morgan D, Freedland CS, et al. Self-administration of two long-acting monoamine transport blockers in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000; 152: 414–21

Wilcox KM, Lindsey KP, Votaw JR, et al. Self-administration of cocaine and the cocaine analog RTI-113: relationship to dopamine transporter occupancy determined by PET neuro-imaging in rhesus monkeys. Synapse 2002; 43: 78–85

Dworkin SI, Lambert P, Sizemore GM, et al. RTI-113 administration reduces cocaine self-administration at high occupancy of dopamine transporter. Synapse 1998; 30: 49–55

Howell LL, Wilcox KM. The dopamine transporter and cocaine medication development: drug self-administration in nonhu-man primates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001; 298: 1–6

Mutschler NH, Bergman J. Effects of chronic administration of the D1 receptor partial agonist SKF 77434 on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002; 160: 362–70

Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD. Dissociation of cocaine-antagonist properties and motoric effects of the D1 receptor partial agonists SKF 83959 and SKF 77434. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000; 293(3): 1017–26

Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, et al. Effects of dopamine D(1-like) and D(2-like) agonists in rats that self-administer cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999; 291: 353–60

Giardina WJ, Williams M. Adrogolide HC1 (ABT-431; DAS-431), a prodrug of the dopamine D i receptor agonist, A-86929: preclinical pharmacology and clinical data. CNS Drug Rev 2001; 7: 305–16

Self DW, Karanian DA, Spencer JJ. Effects of the novel D1 dopamine receptor agonist ABT-431 on cocaine self-administration and reinstatement. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000; 909: 133–44

Khroyan TV, Platt DM, Rowlett JK, et al. Attenuation of relapse to cocaine seeking by dopamine D1 receptor agonists and antagonists in non-human primates. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003; 168(1-2): 124–31

Bergman J, Kamien JB, Spealman RD. Antagonism of cocaine self-administration by selective dopamine D(1) and D(2) antagonists. Behav Pharmacol 1990; 1: 355–63

Soyka M, De Vry J. Flupenthixol as a potential pharmacotreatment of alcohol and cocaine abuse/dependence. Eur Neuropsy-chopharmacol 2000; 10: 325–32

Glowa JR, Wojnicki FH. Effects of drugs on food-and cocaine-maintained responding, III: dopaminergic antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996; 128: 351–8

Schenk S, Gittings D. Effects of SCH 23390 and eticlopride on cocaine-seeking produced by cocaine and WIN 35,428 in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003; 168: 118–23

Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, et al. Role of dopamine D2-like receptors in cocaine self-administration: studies with D2 receptor mutant mice and novel D2 receptor antagonists. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 2977–88

Garcia-Ladona FJ, Cox BF. BP 897, a selective dopamine D3 receptor ligand with therapeutic potential for the treatment of cocaine addiction. CNS Drug Rev 2003; 9: 141–58

Vorel SR, Ashby Jr CR, Paul M. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonism inhibits cocaine-seeking and cocaine-enhanced brain reward in rats. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 9595–603

Xi ZX, Gilbert J, Campos AC. Blockade of mesolimbic dopamine D(3) receptors inhibits stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004 Apr 9 [Epub ahead of print]

Gardner EL, Ashby Jr CR. Heterogeneity of the mesotelen-cephalic dopamine fibers: physiology and pharmacology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2000; 24: 115–8

Levant B. Differential distribution of D3 dopamine receptors in the brains of several mammalian species. Brain Res 1998; 800: 269–74

Ashby Jr CR, Minabe Y, Stemp G, et al. Acute and chronic administration of the selective D3 receptor antagonist SB-277011-A alters activity of midbrain dopamine neurons in rats: an in vivo electrophysiological study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000; 294: 1166–74

Gardner EL. The neurobiology and genetics of addiction: implications of the ‘reward deficiency syndrome’ for therapeutic strategies in chemical dependency. In: Elster J, editor. Addiction: entries and exits. New York: Russell Sage, 1999: 57–119

Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G-J. Imaging studies on the role of dopamine in cocaine reinforcement and addiction in humans. J Psychopharmacol 1999; 13: 337–45

Schneier FR, Siris SG. A review of psychoactive substance use and abuse in schizophrenia: patterns of drug choice. J Nerv Ment Dis 1987; 175: 641–52

Dixon L, Haas G, Weiden PJ, et al. Drug abuse in schizophrenic patients: clinical correlates and reasons for use. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148: 224–30

Ohuoha DC, Maxwell JA, Thomson III LE, et al. Effect of dopamine receptor antagonists on cocaine subjective effects: a naturalistic case study. J Subst Abuse Treat 1997; 14: 249–58

Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Silverman P, et al. Risperidone for the treatment of cocaine dependence: randomized, double-blind trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20: 305–10

Di Chiara G. Drug addiction as a dopamine-dependent associative learning disorder. Eur J Pharmacol 1999; 375: 13–30

Everitt BJ, Wolf ME. Psychomotor stimulant addiction: a neural systems perspective. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 3312–20

Shalev U, Grimm JW, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: a review. Pharmacol Rev 2002; 54: 1–42

Muller CP, Carey RJ, Huston JP. Serotonin as an important mediator of cocaine’s behavioral effects. Drugs Today (Bare) 2003; 39(7): 497–511

Uhl GR, Hall FS, Sora I. Cocaine, reward, movement and monoamine transporters. Mol Psychiatry 2002; 7(1): 21–6

Walsh SL, Cunningham KA. Serotonergic mechanisms involved in the discriminative stimulus, reinforcing and subjective effects of cocaine. Psychopharmacology 1997; 130: 41–58

McGregor A, Lacosta S, Roberts DC. L-tryptophan decreases the breaking point under a progressive ratio schedule of intravenous cocaine reinforcement in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1993; 44: 651–5

Carroll ME, Lac ST, Asencio M, et al. Intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats is reduced by dietary L-tryptophan. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990; 100: 293–300

Lee K, Kornetsky C. Acute and chronic fluoxetine treatment decreases the sensitivity of rats to rewarding brain stimulation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1998; 60: 539–44

Walsh SL, Cunningham KA. Serotonergic mechanisms involved in the discriminative stimulus, reinforcing and subjective effects of cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997; 130: 41–58

Schenk S. Effects of the serotonin 5-HT(2) antagonist, ritanserin, and the serotonin 5-HT(1A) antagonist, WAY 100635, on ocaine-seeking in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2000; 67: 363–9

Carey RJ, De Palma G, Damianopoulos E. 5-HT1A agonist/ antagonist modification of cocaine stimulant effects: implications for cocaine mechanisms. Behav Brain Res 2002; 132: 37–46

Burmeister JJ, Lungren EM, Kirschner KF, et al. Differential roles of 5-HT receptor subtypes in cue and cocaine reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29: 660–8

Frankel PS, Cunningham KA. m-Chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) modulates the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine through actions at the 5-HT2C receptor. Behav Neurosci 2004; 118: 157–62

Filip M, Cunningham KA. Hyperlocomotive and discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine are under the control of sero-tonin(2C) (5-HT(2Q) receptors in rat prefrontal cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003; 306: 734–43

Davidson C, Lee TH, Xiong Z, et al. Ondansetron given in the acute withdrawal from a repeated cocaine sensitization dosing regimen reverses the expression of sensitization and inhibits self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002; 27: 542–53

Lane JD, Pickering CL, Hooper ML, et al. Failure of ondansetron to block the discriminative or reinforcing stimulus effects of cocaine in the rat. Drug Alcohol Depend 1992; 30: 151–62

Cervo L, Pozzi L, Samanin R. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists do not modify cocaine place conditioning or the rise in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1996; 55: 33–7

Phillips GD, Robbins TR, Everitt BJ. Mesoaccumbens dopamine-opiate interactions in the control over behaviour of a conditioned reinforcer. Psychopharmacology 1994; 114: 345–59

Shippenberg TS, Chefer V. Opioid modulation of psychomotor stimulant effects. In: Maldonado R, editor. Molecular biology of drug addiction. Totowa (NJ): Humana Press 2002: 107–33

Napier TC, Mitrovic I. Opioid modulation of ventral pallidal inputs. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999; 877: 176–201

Akil H, Owens C, Gutstein H, et al. Endogenous opioids: overview and current issues. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998; 51: 127–40

Van Ree JM, Niesink RJ, Van Wolfswinkel L, et al. Endogenous opioids and reward. Eur J Pharmacol 2000; 405: 89–101

Okada Y, Tsuda Y, Bryant SD, et al. Endomorphins and related opioid peptides. Vitam Horm 2002; 65: 257–79

Kreek MJ, LaForge KS, Butelman E. Pharmacotherapy of addictions [published erratum appears in Nat Rev Drug Discov 2002 Nov; 1 (11): 920]. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2002; 1: 710–26

Kleber HD. Pharmacologic treatments for heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Addict 2003; 12 Suppl. 2: S5–S18

Modesto-Lowe V, Van Kirk J. Clinical uses of naltrexone: a review of the evidence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 10: 213–27

Rademacher DJ, Steinpreis RE. Effects of the selective mu(1)-opioid receptor antagonist, naloxonazine, on cocaine-induced conditioned place preference and locomotor behavior in rats. Neurosci Lett 2002 Nov 8; 332(3): 159–62

Ward SJ, Martin TJ, Roberts DC. Beta-funaltrexamine affects cocaine self-administration in rats responding on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2003 May; 75(2): 301–7

Woolfolk DR, Holtzman SG. The effects of opioid receptor antagonism on the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine and d-amphetamine in the rat. Behav Pharmacol 1996 Dec; 7(8): 779–87

Mello NK, Negus SS. Interactions between kappa opioid agonists and cocaine: preclinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000; 909: 104–32

Shippenberg TS, Chefer VI, Zapata A, et al. Modulation of the behavioral and neurochemical effects of psychostimulants by kappa-opioid receptor systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001; 937: 50–73

Tzschentke TM. Behavioral pharmacology of buprenorphine, with a focus on preclinical models of reward and addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002; 161: 1–16

Kalivas PW. Neurotransmitter regulation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1993; 18(1): 75–113

Kalivas PW, Duffy P, Eberhardt H. Modulation of A10 dopamine neurons by gamma-aminobutyric acid agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990; 253: 858–66

Brebner K, Childress AR, Roberts DCS. A potential role for GABAb agonists in the treatment of psychostimulant addiction. Alcohol Alcohol 2002; 37(5): 478–84

Dewey SL, Morgan AE, Ashby Jr CR, et al. A novel strategy for the treatment of cocaine addiction. Synapse 1998; 30(2): 119–29

Dewey SL, Chaurasia CS, Chen CE, et al. GABAergic attenuation of cocaine-induced dopamine release and locomotor activity. Synapse 1997; 25: 393–8

Kushner SA, Dewey SL, Kornetsky C. Gamma-vinyl GAB A attenuates cocaine-induced lowering of brain stimulation reward thresholds. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997; 133: 383–8

Kushner SA, Dewey SL, Kornetsky C. The irreversible gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transaminase inhibitor gamma-vinyl-GABA blocks cocaine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999; 290: 797–802

Gardner EL, Schiffer WK, Horan BA, et al. Gamma-vinyl GABA, an irreversible inhibitor of GABA transaminase, alters the acquisition and expression of cocaine-induced sensitization in male rats. Synapse 2002; 46: 240–50

Panagis G, Kastellakis A. The effects of ventral tegmental administration of GABA(A), GABA(B), NMDA and AMPA receptor agonists on ventral pallidum self-stimulation. Behav Brain Res 2002; 131: 115–23

Willick ML, Kokkinidis L. The effects of ventral tegmental administration of GABAA, GABAB and NMDA receptor agonists on medial forebrain bundle self-stimulation. Behav Brain Res 1995; 70: 31–6

Negus SS, Mello NK, Fivel PA. Effects of GABA agonists and GABA-A receptor modulators on cocaine discrimination in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000; 152: 398–407

Giorgetti M, Javaid JI, Davis JM, et al. Imidazenil, a positive allosteric GABAA receptor modulator, inhibits the effects of cocaine on locomotor activity and extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens shell without tolerance liability. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998; 287: 58–66

Grant KA, Johanson CE. Diazepam self-administration and resistance to extinction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1987; 28: 81–6

Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. The GABA(B) receptor agonist baclofen attenuates cocaine- and heroin-seeking behavior by rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28: 510–8

Brebner K, Phelan R, Roberts DC. Effect of baclofen on cocaine self-administration in rats reinforced under fixed-ratio 1 and progressive-ratio schedules. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000; 148: 314–21

Roberts DC, Brebner K. GABA modulation of cocaine self-administration. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000; 909: 145–58

Brebner K, Froestl W, Andrews M, et al. The GABA(B) agonist CGP 44532 decreases cocaine self-administration in rats: demonstration using a progressive ratio and a discrete trials procedure. Neuropharmacology 1999; 38: 1797–804

Campbell UC, Lac ST, Carroll ME. Effects of baclofen on maintenance and reinstatement of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 143: 209–14

Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ. Glutamatergic mechanisms in addiction. Mol Psychiatry 2003; 8: 373–82

Rockhold RW. Glutamatergic involvement in psychomotor stimulant action. Prog Drug Res 1998; 50: 155–92

Cornish JL, Kalivas PW. Cocaine sensitization and craving: differing roles for dopamine and glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. J Addict Dis 2001; 20: 43–54

Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, et al. Neuroadaptations in cystine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nat Neurosci 2003; 6(7): 743–9

McFarland K, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Prefrontal glutamate release into the core of the nucleus accumbens mediates cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J Neurosci 2003; 23(8): 3531–7

Xi Z-X, Ramamoorthy S, Shen H, et al. GABA transmission in the nucleus accumbens is altered after withdrawal from repeated cocaine. J Neurosci 2003; 23(8): 3498–505

Xi Z-X, Ramamoorthy S, Baker DA, et al. Modulation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling by chronic cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303: 608–15

Cornish JL, Kalivas PW. Glutamate transmission in the nucleus accumbens mediates relapse in cocaine addiction. J Neurosci 2000; 20(15): RC89

Bell K, Duffy P, Kalivas PW. Context-specific enhancement of glutamate transmission by cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2000; 23: 335–44

Shippenberg TS, Rea W, Slusher BS. Modulation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine by NAALADase inhibition. Synapse 2000 Nov; 38(2): 161–6

Slusher BS, Thomas A, Paul M, et al. Expression and acquisition of the conditioned place preference response to cocaine in rats is blocked by selective inhibitors of the enzyme N-acetylated-alpha-linked-acidic dipeptidase (NAALADASE). Synapse 2001 Jul; 41(1): 22–8

Kotlinska J, Biala G. Memantine and ACPC affect conditioned place preference induced by cocaine in rats. Pol J Pharmacol 2000; 52: 179–85

Tzchentke TM, Schmidt WJ. Effects of the non-competitive NMDA-receptor antagonist memantine on morphine- and cocaine-induced potentiation of lateral hypothalamic brain stimulation reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000; 149: 225–34

Bespalov AY, Zvartau EE, Balster RL, et al. Effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists on reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior by priming injections of cocaine or exposures to cocaine-associated cues in rats. Behav Pharmacol 2000; 11: 37–44

Hyytia P, Backstrom P, Liljequist S. Site-specific NMDA receptor antagonists produce differential effects on cocaine self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 1999; 378: 9–16

Kim JH, Vezina P. The mGlu2/3 receptor agonist LY379268 blocks the expression of locomotor sensitization by amphetamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2002; 73(2): 333–7

Cartmell J, Monn JA, Schoepp DD. The metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonists LY354740 and LY379268 selectively attenuate phencyclidine versus d-amphetamine motor behaviors in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999; 291: 161–70

McGeehan AJ, Janak PH, Olive MF. Effect of the mGluR5 antagonist 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP) on the acute locomotor stimulant properties of cocaine, d-amphetamine, and the dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909 in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004 Jan 15 [Epub ahead of print]

Kenny PJ, Paterson NE, Boutrel B, et al. Metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor antagonist MPEP decreased nicotine and cocaine self-administration but not nicotine and cocaine-induced facilitation of brain reward function in rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003 Nov; 1003: 415–8

McGeehan AJ, Olive MF. The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP reduces the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine but not other drugs of abuse. Synapse 2003 Mar; 47(3): 240–2

Chiamulera C, Epping-Jordan MP, Zocchi A, et al. Reinforcing and locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine are absent in mGluR5 null mutant mice. Nat Neurosci 2001; 4: 873–4

Baptista MA, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Preferential effects of the metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonist LY379268 on conditioned reinstatement versus primary reinforcement: comparison between cocaine and a potent conventional reinforcer. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 4723–7

Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid receptor ligands: clinical and neuropharmacological considerations, relevant to future drug discovery and development. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2000; 9: 1553–71

Piomelli D, Giuffrida A, Calignano A, et al. The endocannabinoid system as a target for therapeutic drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2000; 21: 218–24

Gardner EL. Addictive potential of cannabinoids: the underlying neurobiology. Chem Phys Lipids 2002; 121: 267–90

De Vries TJ, Shaham Y, Homberg JR, et al. A cannabinoid mechanism in relapse to cocaine seeking. Nat Med 2001; 7: 1151–4

Beinfeld MC. An introduction to neuronal cholecystokinin. Peptides 2001; 22: 1197–200

Noble F, Wank SA, Crawley JN, et al. Structure, distribution, and functions of cholecystokinin receptors. Pharmacol Rev 1999; 51: 745–81

Vaccarino FJ. Nucleus accumbens dopamine-CCK interactions in psychostimulant reward and related behaviors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1994; 18: 207–14

Noble F, Roques BP. CCK-B receptor: chemistry, molecular biology, biochemistry and pharmacology. Prog Neurobiol 1999; 58: 349–79

Josselyn SA, De Cristofaro A, Vaccarino FJ. Evidence for CCKa receptor involvement in the acquisition of conditioned activity produced by cocaine in rats. Brain Res 1997; 763: 93–102

Massey BW, Vanover KE, Woolverton WL. Effects of cholecystokinin antagonists on the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in rats and monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend 1994; 34: 105–11

Crespi F. The role of cholecystokinin (CCK), CCK-A or CCK-B receptor antagonists in the spontaneous preference for drugs of abuse (alcohol or cocaine) in naive rats. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 1998; 20: 679–97

Jackson A, Tattersall D, Bentley G, et al. An investigation into the discriminative stimulus and reinforcing properties of the CCKB-receptor antagonist, L-365,260 in rats. Neuropeptides 1994; 26(5): 343–53

Lu L, Zhang B, Liu Z, et al. Reactivation of cocaine conditioned place preference induced by stress is reversed by cholecystokinin-B receptors antagonist in rats. Brain Res 2002; 954: 132–40

Lu L, Liu D, Ceng X. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1 mediates stress-induced relapse to cocaine-conditioned place preference in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 415: 203–8

Goeders NE, Clampitt DM. Potential role for the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in the conditioned reinforcer-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002; 161: 222–32

Gurkovskaya O, Goeders NE. Effects of CP-154,526 on responding during extinction from cocaine self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 432: 53–6

Goeders NE, Guerin GF. Effects of the CRH receptor antagonist CP-154,526 on intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2000; 23: 577–86

Shaham Y, Erb S, Leung S, et al. CP-154,526, a selective, non-peptide antagonist of the corticotropin-releasing factorl receptor attenuates stress-induced relapse to drug seeking in cocaine- and heroin-trained rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998; 137: 184–90

Bissette G, Nemeroff CB. The neurobiology of neurotensin. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, editors. Psychopharmacology: the fourth generation of progress. New York: Raven Press, 1995: 573–82

Tyler BM, Douglas CL, Fauq A, etal. In vitro binding and CNS effects of novel neurotensin agonists that cross the blood-brain barrier. Neuropharmacology 1999; 38: 1027–34

Gully D, Canton M, Boigegrain R, et al. Biochemical and pharmacological profile of a potent and selective nonpeptide antagonist of the neurotensin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90: 65–9

Gully D, Labeeuw B, Boigegrain R, et al. Biochemical and pharmacological activities of SR 142948A, a new potent neurotensin receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 280: 802–12

Binder EB, Kinkead B, Owens MJ, et al. Neurotensin and dopamine interactions. Pharmacol Rev 2001; 53: 453–86

Sarnyai Z, Shaham Y, Heinrichs SC. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in drug addiction. Pharmacol Rev 2001; 53: 209–43

Sawchenko PE, Imaki T, Potter E, et al. The functional neuroanatomy of corticotropin-releasing factor. In: Chadwick DJ, Marsh J, Ackrill K, editors. Corticotropin-releasing factor. Chichester: Wiley, 1993: 5–29

Koob GF, Heinrichs SC. A role for corticotropin-releasing factor and urocortin in behavioral responses to Stressors. Brain Res 1999; 848: 141–52

Piazza PV, Le Moal M. Pathophysiological basis of vulnerability to drug abuse: interaction between stress, glucocorticoids, and dopaminergic neurons. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1996; 36: 359–78

Piazza PV, Le Moal M. Glucocorticoids as abiological substrate of reward: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Brain Res Rev 1997; 25: 359–72

Richter RM, Weiss F. In vivo CRF release in rat amygdala is increased during cocaine withdrawal in self-administering rats. Synapse 1999; 32: 254–61

Sarnyai Z, Biro E, Gardi J, et al. Brain corticotropin-releasing factor mediates ‘anxiety-like’ behavior induced by cocaine withdrawal in rats. Brain Res 1995; 675: 89–97

Broadbear JH, Winger G, Rice KC, et al. Antalarmin, a putative CRH-RI antagonist, has transient reinforcing effects in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 2002; 164: 268–76

Henderson CE. Role of neurotrophic factors in neuronal development. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1996; 6: 64–70

Martin-Iverson MT, Todd KG, Altar CA. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 activate striatal dopamine and serotonin metabolism and related behaviors: interactions with amphetamine. J Neurosci 1994; 14: 1262–70

Horger BA, Iyasere CA, Berhow MT, et al. Enhancement of locomotor activity and conditioned reward to cocaine by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci 1999; 19: 4110–22

Grimm JW, Lu L, Hayashi T, et al. Time-dependent increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein levels within the mesolimbic dopamine system after withdrawal from cocaine: implications for incubation of cocaine craving. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 742–7

Grimm JW, Hope BT, Wise RA, et al. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature 2001; 412: 141–2

Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, et al. One-year follow-up of disulfiram and psychotherapy for cocaine-alcohol users: sustained effects of treatment. Addiction 2000; 95: 1335–49

Carroll KM, Ziedonis D, O’Malley SS, et al. Pharmacologic interventions for abusers of alcohol and cocaine: a pilot study of disulfiram versus naltrexone. Am J Addict 1993; 2: 77–9

Gorelick DA. Alcohol and cocaine: clinical and pharmacological interactions. Recent Dev Alcohol 1992; 11: 37–56

George TP, Chawarski MC, Pakes J, et al. Disulfiram versus placebo for cocaine dependence in buprenorphine-maintained subjects: a preliminary trial. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47: 1080–6

Petrakis IL, Carroll KM, Nich C, et al. Disulfiram treatment for cocaine dependence in methadone-maintained opioid addicts. Addiction 2000; 95: 219–28

Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, et al. Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive behavior therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61: 264–72

McCance-Katz EF, Kosten TR, Jatlow P. Chronic disulfiram treatment effects on intranasal cocaine administration: initial results. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43: 540–3

Houtsmuller EJ, Notes LD, Newton T, et al. Transdermal selegiline and intravenous cocaine: safety and interactions. Psychopharmacology 2004; 172: 31–40

Elkashef A, Fudala P, Gorgon S, et al. Transdermal selegiline for the treatment of cocaine dependence [poster]. Presented at College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 65th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2003 Jun 14–19; Bal Harbour

Montgomery A, Elkashef A, Ciraulo DA, et al. 2004 update of NIDA phase II medications development program for treatment of cocaine dependence [poster]. Presented at College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 66th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2004 Jun 12–17, San Juan

Ceravolo R, Piccini P, Bailey DL, et al. 18F-Dopa PET evidence that tolcapone acts as a central COMT inhibitor in Parkinson’s disease. Synapse 2002; 43: 201–7

Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Kolsky AR, et al. Open study of the catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor tolcapone in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19: 329–35

Cousins MS, Roberts DCS, de Wit H. GABAb receptor agonists for the treatment of drug addiction: a review of recent findings. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 65: 209–20

Ling W, Shoptaw S, Majewska D. Baclofen as a cocaine anti-craving medication: a preliminary clinical study. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 18: 403–4

Shoptaw S, Yang X, Rotheram-Fuller EJ, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of baclofen for cocaine dependence: Preliminary effects for individuals with chronic patterns of cocaine use. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64: 1440–8

Gonzalez G, Sevarino K, Sofuoglu M, et al. Tiagabine increases cocaine-free urines in cocaine-dependent methadone-treated patients: results of a randomized pilot study. Addiction 2003; 98: 1625–32

onzalez G, Sofuoglu M, Gonsai K, et al. Efficacy of tiagabine or gabapentin in reducing cocaine use in methadone-stabilized cocaine abusers [poster]. Presented at College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 65th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2003 Jun 14–19, Bal Harbour

Tennant F, Tarver A, Sagherian A, et al. A placebo-controlled elimination study to identify potential treatment agents for cocaine detoxification. Am J Addict 1993; 2: 299–308

Reid MS, Leiderman D, Casadonte P, et al. A controlled trial of olanzapine, valproate or coenzyme Q10/L-carnitine versus placebo for the treatment of cocaine dependence [abstract]. Drug Alcohol Depend 2000; 60 Suppl. 1: S179

Myrick H, Henderson S, Brady KT, et al. Divalproex loading in the treatment of cocaine dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs 2001; 33: 283–7

Halikas JA, Center BA, Pearson VL, et al. A pilot, open clinical study of depakote in the treatment of cocaine abuse. Hum Psychopharmacol 2001; 16: 257–64

Kampman KM, Pettinati H, Lynch KG, et al. A pilot trial of topiramate for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. In press

Brodie JD, Figueroa E, Dewey SL. Treating cocaine addiction: from preclinical to clinical trial experience with γ-vinyl GABA. Synapse 2003; 50: 261–5

Raby WN, Coomaraswamy S. Gabapentin reduces cocaine use among addicts from a community clinic sample. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65: 84–6

Bisaga A, Aharonovich E, Nune E. Gabapentin treatment of cocaine dependence [poster]. Presented at College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 65th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2003 Jun 14–19, Bal Harbour

Onsai K, Oliveto A, Poling J, et al. Efficacy of sertraline in depressed, recently abstinent, cocaine-dependent patients [abstract]. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 66 Suppl. 1: S67

Pulvirenti L, Balducci C, Koob GF. Dextromethorphan reduces intravenous cocaine self-administration in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 1997; 321: 279–83

Kilpatrick GJ, Tilbrook GS. Memantine: Merz. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2002; 3: 798–806

Collins ED, Ward AS, McDowell DM, et al. The effects of memantine on the subjective, reinforcing and cardiovascular effects of cocaine in humans. Behav Pharmacol 1998; 9: 587–98

Johnson BA, Devous MD, Ruiz P, et al. Treatment advances for cocaine-induced ischemic stroke: focus on dihydropyridine-class calcium channel antagonists. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1191–8

Gottschalk PCH, Kosten TR. Isradipine enhancement of cerebral blood flow in abstinent cocaine abusers with and without chronic perfusion deficits. Am J Addict 2002; 11: 200–8

Malcolm R, Brady KT, Moore J, et al. Amlodipine treatment of cocaine dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs 1999; 31: 117–20

Johnson BA, Roache JD, Wells L, et al. Sub-acute dosing with isradipine blocks cocaine euphoria and craving in phase II lab trials for medications to treat cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 66 Suppl. 1: S86–7

Ait-Daoud N, Wells L, Roache JD, et al. Sub-acute dosing with isradipine modestly decreases pressor response in a phase II lab trials for medications to treat cocaine dependence [abstract]. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 66 Suppl. 1: S4

Batki SL, Bradley M, Moon J, et al. A controlled trial of isradipine in cocaine dependence: preliminary analysis [abstract]. NIDA Res Monogr 1998; 179: 56

Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Schmitz J, et al. Dextroamphetamine for cocaine-dependence treatment: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001; 21: 522–6

Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Schmitz J, et al. Methods for early phase medication development trials examined using the agonist approach for cocaine dependence [abstract]. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 66 Suppl. 1: S68

Shearer J, Wodak A, Van Beek I, et al. Pilot randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of dexamphetamine for cocaine dependence. Addiction 2003; 98: 1137–41

Walsh SL, Haberny KA, Bigelow GE. Modulation of intravenous cocaine effects by chronic oral cocaine in humans. Psychopharmacology 2000; 150: 361–73

Uemura N, Manari A, Shih K, et al. The safety and efficacy of sustained cocaine agonist exposures in suppressing cocaine craving and self-administration in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 66 Suppl. 1: S185

Dackis C, O’Brien C. Glutamatergic agents for cocaine dependence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003; 1003: 328–45

Rush CR, Kelly TH, Hays LR, et al. Discriminative-stimulus effects of modafinil in cocaine-trained humans. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 67: 311–22

Jasinski DR, Kovacevic-Ristanovic R. Evaluation of the abuse liability of modafinil and other drugs for excessive daytime sleepiness associated with narcolepsy. Clin Neuropharmacol 2000; 23: 149–56

Dackis C, Lynch KG, Yu E, et al. Modafinil and cocaine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled drug interaction study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003; 70: 29–37

Malcolm RJ, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Influence of modafinil, 400 or 800 mg/day on subjective effects of intravenous cocaine in non-treatment-seeking volunteers [abstract]. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 66 Suppl. 1: S110

Camacho A, Stein MB. Modafinil for social phobia and amphetamine dependence. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 1947–8

Malcolm R, Book SW, Moak D, et al. Clinical applications of modafinil in stimulant abusers: low abuse potential. Am J Addict 2002; 11: 247–9

Kampman KM, Volpicelli JR, Mulvaney F, et al. Effectiveness of propranolol for cocaine dependence treatment may depend on cocaine withdrawal symptom severity. Drug Alcohol Depend 2001; 63: 69–78

Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence [poster]. Presented at College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 66th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2004 Jun 12–17, San Juan

Compton PA, Ling W, Charuvastra VC, et al. Buprenorphine as a pharmacotherapy for cocaine abuse: a review of the evidence. J Addict Dis 1995; 14: 97–114

Montoya I, Gorelick D, Preston K, et al. Randomized trial of buprenorphine for treatment of concurrent opiate and cocaine dependence. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004; 75: 34–48

Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Citicoline mechanisms and clinical efficacy in cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci Res 2002; 70: 133–9

Clark WM, Wechsler LR, Sabounjian LA, et al. A phase III randomized efficacy trial of 2000 mg citicoline in acute ischemic stroke patients. Neurology 2001; 57: 1595–602

Penetar D, Rodolico J, Eaton J, et al. Citicoline treatment for cocaine dependence: safey and effects on sleep and subjective mood states [abstract]. Presented at College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 65th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2003 Jun 14–19; Bal Harbour

Lukas SE, Kouri EM, Rhee C, et al. Effects of short-term citicoline treatment on acute cocaine intoxication and cardiovascular effects. Psychopharmacology 2001; 157: 163–7

Majewska MD. HPA axis and stimulant dependence: an enigmatic relationship. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2002; 27: 5–12

Mendelson JH, Mello NK, Sholar MB, et al. Temporal concordance of cocaine effects on mood states and neuroendocrine hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2002; 27: 71–82

Ward AS, Collins ED, Haney M, et al. Ketoconazole attenuates the cortisol response but not the subjective effects of smoked cocaine in humans. Behav Pharmacol 1998; 9: 577–86

Ward AS, Collins ED, Haney M, et al. Blockade of cocaine-induced increases in adrenocorticotrophic hormone and cortisol does not attenuate the subjective effects of smoked cocaine in humans. Behav Pharmacol 1999; 10: 523–9

Shoptaw S, Majewska MD, Wilkins J, et al. Participants receiving dehydroepiandrosterone during treatment for cocaine dependence show high rates of cocaine use in a placebo-controlled pilot study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 12: 126–35

Goeders NE. Stress and cocaine addiction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 301: 785–9

Preti A. Vanoxerine: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2000; 1: 241–51

Cantilena LR, Haigney M, Elkashef A, et al. Clinical safety of multiple escalating doses of GBR12909 in healthy volunteers [abstract]. Drug Alcohol Depend 2001; 63 Suppl. 1: S24

Madras BK, Bendor JT, Meyerhoff AR, et al. The tropane horse: a novel cocaine antagonist strategy? [abstract]. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 66 Suppl. 1: S24

Woolverton WL, Ranaldi R, Wang Z, et al. Reinforcing strength of a novel dopamine transporter ligand: pharmacodynantic and pharmacokinetic mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303: 211–7

Haney M, Collins ED, Ward AS, et al. Effect of a selective dopamine Di agonist (ABT-431) on smoked cocaine self-administration in humans. Psychopharmacology 1999; 143: 102–10

Eder DN. CEE-03-310 CeNeS Pharmaceuticals. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2002; 3: 284–8

Haney M, Ward AS, Foltin RW, et al. Effects of ecopipam, a selective dopamine D1 antagonist, on smoked cocaine self-administration by humans. Psychopharmacology 2001; 155: 330–7

Nann-Vernotica E, Donny EC, Bigelow GE, et al. Repeated administration of the D1/5 antagonist ecopipam fails to attenuate the subjective effects of cocaine. Psychopharmacology 2001; 155: 338–47

Neumeyer JL, Gu X-H, van Vliet LA, et al. Mixed K agonists and μ agonists/antagonists as potential pharmacotherapeutics for cocaine abuse: synthesis and opioid receptor binding affinity of N-substituted derivatives of morphinan. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2001; 11: 2735–40

Walsh SL, Geter-Douglas B, Strain EC, et al. Enadoline and butorphanol: evaluation of K-agonists on cocaine pharmaco-dynamics and cocaine self-administration in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001; 299: 147–58

Lavarone L, Hoke JF, Bottacini M, et al. First time in human for GV196771: interspecies scaling applied on dose selection. J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 39: 560–6

Gorelick DA. Enhancing cocaine metabolism with butyryl-cholinesterase as a treatment strategy. Drug Alcohol Depend 1997; 48: 159–65

Carmona GN, Schindler CW, Shoaib M, et al. Attenuation of cocaine-induced locomotor activity by butyrylcholinesterase. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 6: 274–9

Carrera MRA, Ashley JA, Wirsching P, et al. A second-generation vaccine protects against the psychoactive effects of cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98: 1988–92

Deng SX, de Prada P, Landry DW. Anticocaine catalytic antibodies. J Immunol Methods 2002; 269: 299–310

Sun H, Shen ML, Pang Y-P, et al. Cocaine metabolism accelerated by a re-engineered human butyrylcholinesterase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 302: 710–6

Turner JM, Larsen NA, Basran A, et al. Biochemical characterization and structural analysis of a highly proficient cocaine esterase. Biochemistry 2002; 41: 12297–307

Kantak KM. Anti-cocaine vaccines: antibody protection against relapse. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2003; 4: 213–8

Ho M, Segre M. Inhibition of cocaine binding to the human dopamine transporter by a single chain anti-idiotypic antibody: its cloning, expression, and functional properties. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003; 1638: 257–66

Kosten TR, Rosen M, Bond J, et al. Human therapeutic cocaine vaccine: safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine 2002; 20: 1196–204

Kosten T. Immunotherapies for substance abuse: human cocaine vaccine [abstract]. Presented at College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 65th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2003 Jun 14–19; Bal Harbour

Martell BA, Mitchell E, Poling J, et al. Vaccine pharmacotherapy for the treatment of cocaine dependence [poster]. Presented at College on Problems of Drug Dependence, 66th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2004 Jun 12–17, San Juan

BioSpace. Large, unreachable markets? What biotechs are doing [online]. Available from URL: http://www.biospace.com/articles/091699_biotechaddiction.cfm [Accessed 2002 Dec11]

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by intramural funds of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health, USA. We thank Drs Ahmed Elkashef and Francis Vocci of the US NlDA for information about the institute’s medication development programmes. Dr Gardner has received past research grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals for anti-cocaine addiction pharmacotherapeutic drug discovery and development.

The authors have no current conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gorelick, D.A., Gardner, E.L. & Xi, ZX. Agents in Development for the Management of Cocaine Abuse. Drugs 64, 1547–1573 (2004). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200464140-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200464140-00004