Procalcitonin in general internal medicine: a bibliometric analysis

Introduction

General internal medicine (GIM) is receiving more and more attention from countries worldwide (1-3). GIM doctors are mainly general practitioners and are primarily responsible for the initial patient consultation, particularly for those patients with atypical or unclear symptoms. After initial diagnosis and treatment, some patients are cured, and others transfer to specialist departments for further diagnosis and treatment (4). Consequently, in the medical systems of most countries, GIM and GIM physicians are at the forefront of disease diagnosis and treatment (5). During the current COVID-19 pandemic, many GIM doctors were infected because they were not sufficiently protected, and the losses were enormous (6).

In GIM, infectious diseases and unexplained fever are the most common problems, and clinical practice involves determining whether there is a possibility of bacterial infection and overseeing the use of antibacterial drugs (7). Procalcitonin (PCT) is a peptide precursor, produced by thyroid C cells. In some stress situations, such as sepsis and septic shock, the PCT level will increase, and the more severe the infection, the higher the patient’s PCT level. PCT has high specificity and sensitivity in identifying bacterial infection and is recommended for both the identification of infection and monitoring of treatment (7). There are many studies on severe and secondary infection following viral infection; however, there is relatively little research based on GIM. The clinical significance of PCT in different environments may vary, and the evidence generated by research from different medical fields may not be applicable or well suited to other situations. A previous similar bibliometric analysis revealed that study of PCT mainly focused on respiratory infections, especially sepsis and pneumonia (8). This research aimed to understand the current research status and provide references for researchers by analyzing the overall situation of relevant documents classified in the GIM field.

Methods

Database

The Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) database in the Web of Science Core Collection (WOSCC) was used as the source for the literature search. SCIE, founded in 1957, is a bibliographic database published by the American Institute of Scientific Information. It contains the titles and citations of more than 8,000 important journals in the field of natural sciences. SCIE is an important citation retrieval tool and an important basis for metrological research and scientific research evaluation.

Search strategy

The method used in this study was subject search + limited search. The search term used for the subject search was PCT, and the limited search scope was Medicine, General & Internal. The publication date range was unlimited (from 1900 to the date of the last search of this study, May 16, 2021).

Analysis method

We exported article and citation records obtained from the search results and used CiteSpace software to analyze the annual paper publication status, country, institution, author distribution, journal distribution, and keyword usage for PCT research in the GIM field.

Statistical processing

This study primarily describes the current status of relevant indicators, and the main form of data presentation is the quantity (percentage) without comparative analysis.

Results

Literature search results

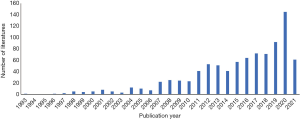

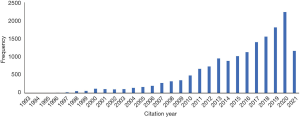

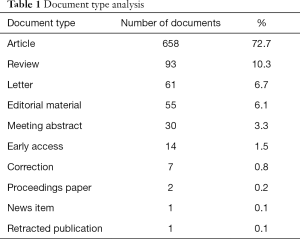

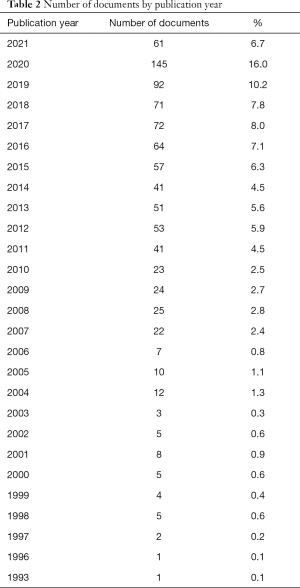

A total of 905 relevant research documents were obtained through the search, including 658 original articles, 93 reviews, 61 letters, 55 editorial materials, 30 meeting abstracts, 14 early access, 7 corrections, and 2 proceedings papers, 1 news item, and 1 retraction publication (the initial total number in Table 1 is 922, 17 of which were classified repeatedly; the actual number of documents was 905). The distribution of the number of annual papers showed that the volume of research in this field is generally increasing year by year, with a relatively large increase in 2020, which might have been due to the COVID-19 pandemic in that year (Table 2, Figure 1). The citation frequency showed a more obvious trend of the increasing year by year, suggesting that related research is getting more and more attention. The number of citations for the papers was 15,917, the h-index was 50, and the average number of citations per paper was 17.59 (Figure 2).

Full table

Full table

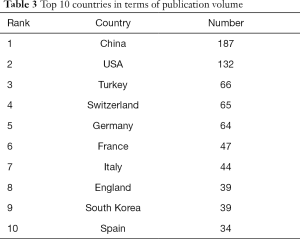

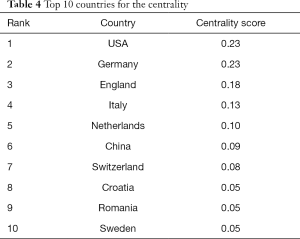

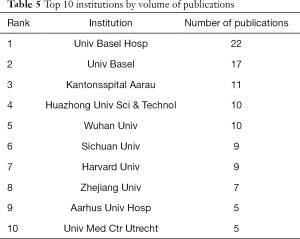

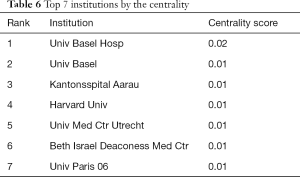

Distribution of the literature in countries and institutions

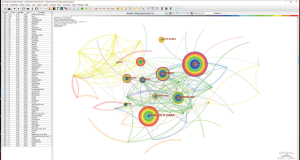

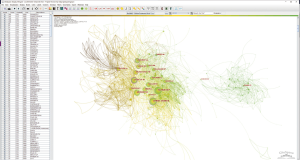

The articles were counted separately by country and institution, and CiteSpace V software was used to create a national visualization map (Figure 3) and an institutional visualization map (Figure 4). The results found that the top 5 countries for the number of papers published were China, the United States, Turkey, Switzerland, and Germany (Table 3). The top 5 countries for centrality were the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, and the Netherlands (Table 4). The top 5 institutions for the number of papers published were University Hospital Basel, the University of Basel, Kantonsspital Aarau, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and Wuhan University (Table 5). All research institutions had a low centrality score, with only University Hospital Basel obtaining 0.02 and 6 other institutions 0.01 (Table 6, Figure 4). The centrality scores of other research institutions are all lower than 0.01, indicating that there is little cooperation between institutions in this field of research.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Full table

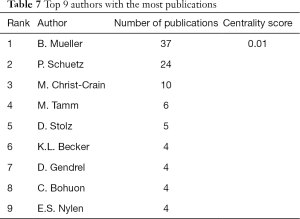

Author distribution

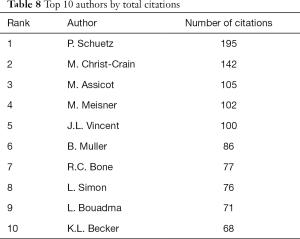

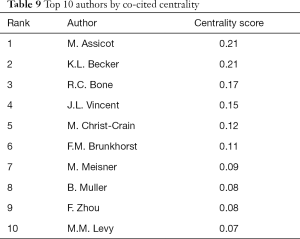

We performed statistical analysis on the number of papers published by the authors and the number of times they were cited and then created a visual map. The results showed that there were only three authors with more than 10 papers: B. Mueller, P. Schuetz, and M. Christ-Crain. In fact, according to the author information provided in the literature, the top 5 authors in Table 7 were all from the University of Basel. However, in terms of cooperation status, only Mueller’s centrality score reached 0.01, while the scores of all other authors were less than 0.01. Using data from the coauthored visualization map, it can be seen that the research work is relatively scattered, and authors from different research institutions have little cooperation with each other (Table 7, Figure 5). In terms of co-citation frequency, Schuetz has significantly more citations than the other authors. According to the information provided in the records, this is due to his frequent status as first author or corresponding author (Table 8). The co-citation centrality results show that M. Assicot has the highest score. Assicot’s research was published relatively early, and initial research is often key to the field (Table 9, Figure 6).

Full table

Full table

Full table

Journal distribution

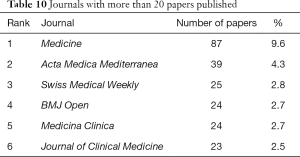

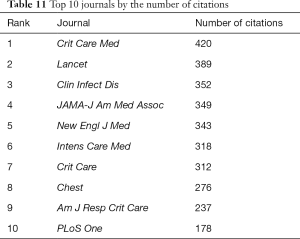

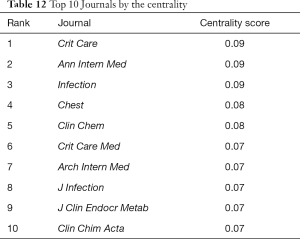

Analysis of the distribution of the journals showed that the 905 articles retrieved in this study were from 126 journals, of which 6 journals had published more than 20 articles each in this field, accounting for a total of 222 journal articles (24.5% of the total number of articles) (Table 10). Judging from the frequency of citations and the results of centrality analysis, leading journals in critical care medicine and quality comprehensive journals are worthy of attention (Tables 11,12).

Full table

Full table

Full table

Keywords reflect the research hotspots and frontiers in this field

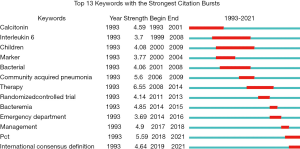

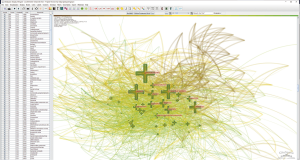

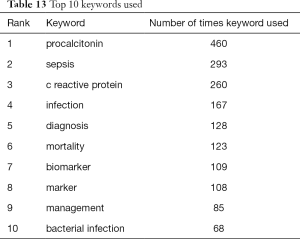

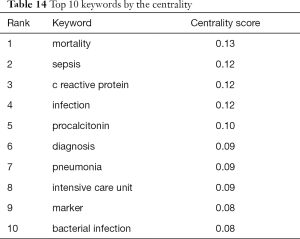

We used CiteSpace V software to draw a keyword co-occurrence map (Figure 7) and then analyzed the frequency and centrality of keywords (Tables 13,14). CiteSpace was used for burst detection of keywords with a high usage rate (Figure 8). The results showed that in this field, apart from PCT itself, the areas of research focus were sepsis, c reactive protein, infection, diagnosis, and mortality. Burst test results showed that the continuity of high-frequency keywords gradually changed over time. The current focus of academic research is the formulation and use of relevant consensus.

Full table

Full table

Discussion

There is no clear conclusion on the biological effects of PCT. The main biological effects are: the role of secondary inflammatory factors, the role of chemokines, anti-inflammatory and protective effects. But plenty of studies support its use in clinical practice. Previous studies have paid considerable attention to PCT application in areas such as critical care medicine and infectious disease (9,10). This study aimed to analyze the status of PCT-related research in GIM. The search results revealed that 905 documents could be classified in this field, of which only 658 were original articles, and that the number of documents increased sharply after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Our research also found that although China, Turkey, and other countries published many papers, their centrality ranking did not enter the top 5, suggesting that the research is done in these countries mainly involves domestic cooperation and that there is less cooperation with foreign countries. Cooperation is mainly carried out in European countries and the United States. However, analysis of research institutions found that the concentration of cooperation between institutions is relatively low. The author analysis showed that leading researchers were essentially from major research institutions, particularly the University of Basel. The journal analysis showed that key research in this area was mainly published in top-tier critical care medicine journals and comprehensive journals, which is a concern. However, keyword analysis results showed that the focus of attention in this field is not significantly different from other fields and is also on infection-related diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment (11-14).

GIM is a discipline that provides primary healthcare services on the front line (15). GIM physicians are often their patients’ regular physicians and, as such, are responsible for initial diagnosis and treatment services (1). During the COVID-19 pandemic, these doctors have been the fighters at the forefront (16). In the clinical practice of GIM, infections are the most common diagnoses, and relevant research and guidelines on PCT application are much needed. However, there were very few relevant or targeted studies (17). Our in-depth analysis of the literature showed that most research in this area was on the application of PCT in critically ill patients. The locations of these studies were mostly medical centers, and the patients were most severely ill patients, such as patients with sepsis, severe pneumonia, and COVID-19 infection. The patients served by GIM have the following characteristics: various diseases; wide age distribution; many patients with atypical clinical manifestations; and many patients with unknown etiology (4,18). Particularly in patients with fever of unknown origin, it is often necessary to rule out infection immediately (19). It is very important to conduct simple and accurate PCT detection in GIM practice, especially for GIM doctors in small medical institutions, as it is essential to determine the nature of fever as soon as possible (20).

In addition, bedside testing or point-of-care testing is often more conducive to the work of frontline GIM physicians, who can more quickly determine whether a patient’s particular index has clinical significance (21). Some studies that have observed the application value of point-of-care detection of PCT in clinical practice (22,23) have shown that it is unsuitable for distinguishing urinary tract infections or asymptomatic bacteriuria (23). However, other studies have found that in the emergency department, the results of point-of-care detection of whole blood PCT are as accurate as laboratory test results, and PCT can predict 28-day death and bacteremia in patients with suspected infection risk (24). Two studies conducted by Waterfield et al. showed that for the diagnosis of suspicious infections in children and young infants, point-of-care detection of PCT also had good accuracy (25,26).

In general, although some studies were classified in the field of GIM, there were relatively few targeted studies, little cooperation between existing studies, and the evidence was weak. Future research should focus more on the application of PCT in GIM to generate more evidence and provide a basis for guiding frontline medical personnel. In conclusion, our present study outlined a birdview of PCT researches in GIM and GIM-related research of PCT should be paid more attention to. There were some limitations in this study. As mentioned above, although the search scope was limited, some of the retrieved documents were more focused on intensive care medicine. Of course, there are also critically ill patients in GIM, but relatively speaking, there might have been some biases in the literature selection, which was closely related to document classification.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-1689). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Wingo MT, Bornstein SL, Szostek JH, et al. Update in Outpatient General Internal Medicine: Practice-Changing Evidence Published in 2019. Am J Med 2020;133:789-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kravitz RL, Feldman MD, et al. General internal medicine as an engine of innovation. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:749-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zumbrunn B, Stalder O, Limacher A, et al. The well-being of Swiss general internal medicine residents. Swiss Med Wkly 2020;150:w20255 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duława J. Who needs general internal medicine? Pol Arch Med Wewn 2016;126:921-4. [PubMed]

- Wise J. Life as a physician in general internal medicine. BMJ 2020;368:m19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monterrosa-Castro A, Redondo-Mendoza V, Mercado-Lara M, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in general practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Investig Med 2020;68:1228-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fultz SL, Goulet JL, Weissman S, et al. Differences between infectious diseases-certified physicians and general medicine-certified physicians in the level of comfort with providing primary care to patients. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:738-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tujula B, Hämäläinen S, Kokki H, et al. Review of clinical practice guidelines on the use of procalcitonin in infections. Infect Dis (Lond) 2020;52:227-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wirz Y, Meier MA, Bouadma L, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on clinical outcomes in intensive care unit patients with infection and sepsis patients: a patient-level meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care 2018;22:191. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang I, Pranata R, Lim MA, et al. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, D-dimer, and ferritin in severe coronavirus disease-2019: a meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2020;14:1753466620937175 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mierzchała-Pasierb M, Lipińska-Gediga M, et al. Sepsis diagnosis and monitoring - procalcitonin as standard, but what next? Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther 2019;51:299-305. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bartoletti M, Antonelli M, Bruno Blasi FA, et al. Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy: an expert consensus. Clin Chem Lab Med 2018;56:1223-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pepper DJ, Sun J, Rhee C, et al. Procalcitonin-Guided Antibiotic Discontinuation and Mortality in Critically Ill Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest 2019;155:1109-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zare ME, Wang Y, Nasir Kansestani A, et al. Procalcitonin Has Good Accuracy for Prognosis of Critical Condition and Mortality in COVID-19: A Diagnostic Test Accuracy Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020;19:557-69. [PubMed]

- Essien UR, Tipirneni R, Leung LB, et al. Surviving and Thriving as Physicians in General Internal Medicine Fellowship in the Twenty-First Century. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:3664-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JI, Bullington BW, Simon MS, et al. COVID-19 Infections Among General Internal Medicine Faculty at a New York Teaching Hospital: a Descriptive Report. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36:1153-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Esteban R, Sarabia PR, Delgado EG, et al. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as diagnostic tools in febrile patients admitted to a General Internal Medicine ward. Clin Biochem 2012;45:22-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Card SE, Clark HD, Elizov M, et al. The Evolution of General Internal Medicine (GIM)in Canada: International Implications. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:576-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fusco FM, Pisapia R, Nardiello S, et al. Fever of unknown origin (FUO): which are the factors influencing the final diagnosis? A 2005-2015 systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2019;19:653. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu L, Shi Q, Shi M, et al. Diagnostic Value of PCT and CRP for Detecting Serious Bacterial Infections in Patients With Fever of Unknown Origin: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2017;25:e61-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh M, Anand L, et al. Bedside procalcitonin and acute care. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2014;4:233-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuil SD, Hidad S, Fischer JC, et al. Sensitivity of point-of-care testing C reactive protein and procalcitonin to diagnose urinary tract infections in Dutch nursing homes: PROGRESS study protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031269 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuil SD, Hidad S, Fischer JC, et al. Sensitivity of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin measured by Point-of-Care tests to diagnose urinary tract infections in nursing home residents: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shim BS, Yoon YH, Kim JY, et al. Clinical Value of Whole Blood Procalcitonin Using Point of Care Testing, Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score, C-Reactive Protein and Lactate in Emergency Department Patients with Suspected Infection. J Clin Med 2019;8:833. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waterfield T, Maney JA, Lyttle MD, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy of point-of-care procalcitonin to diagnose serious bacterial infections in children. BMC Pediatr 2020;20:487. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waterfield T, Maney JA, Hanna M, et al. Point-of-care testing for procalcitonin in identifying bacterial infections in young infants: a diagnostic accuracy study. BMC Pediatr 2018;18:387. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editors: A. Muijlwijk and J. Chapnick)