Abstract

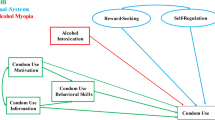

OBJECTIVE: To develop and apply a method to quantify bias parameters in the case example of the association between alcohol use and HIV-serodiscordant condomless anal sex with potential confounding by sensation seeking among men who have sex with men (MSM), using expert opinion as an external data source.

METHODS: Through an online survey, we sought the input of 41 epidemiologist and behavioural scientists to quantify six parameters in the population of MSM: the proportion of high sensation seeking among heavy-drinking MSM, the proportion of sensation seeking among low-level drinking MSM, and the risk ratio (RR) of the association between sensation seeking and condomless anal sex, for HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM.

RESULTS: Eleven experts responded. For HIV-positive heavy drinkers, the proportion of high sensation seeking was 53.6% (beta distribution [α = 5.50, β = 4.78]), and 41.1% (beta distribution [α = 3.10, β = 4.46]) in HIV-negative heavy drinkers. In HIV-positive low-level alcohol drinkers, high sensation seeking was 26.9% (beta distribution [α = 1.81, β = 4.92]), similar to high sensation seeking among HIV-negative low-level alcohol drinkers (25.3%) (beta distribution [α = 2.00, β = 5.89]). The lnRR for the association between sensation seeking and condomless anal sex was ln(2.4) (normal distribution [μ = 0.889, α = 0.438]) in HIV-positive and ln(1.5) (normal distribution [μ = 0.625, σ = 0.391]) in HIV-negative MSM.

CONCLUSION: Expert opinion can be a simple and efficient method for deriving bias parameters to quantify and adjust for hypothesized confounding. In this test case, expert opinion confirmed sensation seeking as a confounder for the effect of alcohol on condomless anal sex and provided the parameters necessary for probabilistic bias analysis.

Résumé

OBJECTIF: En utilisant l’opinion d’experts comme source de données externe, élaborer et appliquer une méthode pour chiffrer les paramètres de biais dans le cas de l’association entre la consommation d’alcool et le sexe anal sans condom entre partenaires sérodifférents pour le VIH, avec un facteur de confusion possible, la recherche de sensations, chez les hommes ayant des relations sexuelles avec des hommes (HARSAH).

MÉTHODE: Au moyen d’un sondage en ligne, nous avons sollicité l’opinion de 41 épidémiologistes et spécialistes du comportement pour chiffrer six paramètres dans la population des HARSAH: la proportion de chercheurs de sensations fortes chez les HARSAH grands buveurs d’alcool, la proportion de chercheurs de sensations chez les HARSAH petits buveurs d’alcool, et le risque relatif (RR) de l’association entre la recherche de sensations et le sexe anal sans condom chez les HARSAH séropositifs et séronégatifs.

RÉSULTATS: Onze spécialistes ont répondu. Chez les grands buveurs séropositifs, la proportion de chercheurs de sensations fortes était de 53,6 % (distribution bêta [α =5,50, β =4,78]); elle était de 41,1 % (distribution bêta [α =3,10, β= 4,46]) chez les grands buveurs séronégatifs. Chez les petits buveurs séropositifs, les chercheurs de sensations fortes représentaient 26,9 % (distribution bêta [α =1,81, β =4,92]), ce qui est comparable aux chercheurs de sensations fortes chez les petits buveurs séronégatifs (25,3 %) (distribution bêta [α= 2,00, β =5,89]). Le logarithme du risque relatif (lnRR) de l’association entre la recherche de sensations et le sexe anal sans condom était ln(2,4) (distribution normale [μ = 0,889, σ = 0,438]) chez les HARSAH séropositifs et ln(1,5) (distribution normale [μ =0,625, σ =0,391]) chez les HARSAH séronégatifs.

CONCLUSION: L’opinion d’experts peut être une méthode simple et efficace pour dériver des paramètres de biais afin de chiffrer les facteurs de confusion hypothétiques et d’apporter les ajustements nécessaires. Dans ce cas type, l’opinion d’experts a confirmé que la recherche de sensations est un facteur de confusion de l’effet de l’alcool sur le sexe anal sans condom, et cette opinion a fourni les paramètres nécessaires à une analyse du biais probabiliste.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chen YH, Vallabhaneni S, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Predictors of serosorting and intention to serosort among men who have sex with men, San Francisco. AIDS Educ Prev 2012;24(6):564–73. PMID: 23206204. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012. 24.6.564.

Snowden JM, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Prevalence of seroadaptive behaviours of men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2004. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85(6):469–76. PMID: 19505875. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009. 036269.

Hittner JB, Swickert R. Sensation seeking and alcohol use: A meta-analytic review. Addict Behav 2006;31(8):1383–401. PMID: 16343793. doi: 10.1016/j. addbeh.2005.11.004.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi L, Jooste S, Vermaak R, Cain D. Sensation seeking and alcohol use predict HIV transmission risks: Prospective study of sexually transmitted infection clinic patients, Cape Town, South Africa. Addict Behav 2008;33(12):1630–33. PMID: 18790575. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh. 2008.07.020.

Amon J, Brown T, Hogle J, MacNeil J, Magnani R, Mills S, et al. Behavioral surveillance surveys (BSS): Guidelines for repeated behavioral surveys in populations at risk of HIV. Arlington, VA, Family Health International [FHI], Implementing AIDS Prevention and Care Project [IMPACT], 2000. 350 p. (USAID Cooperative Agreement No. HRN-A-00-97-00017-00; DFID Contract No. CNTR 973095 A).

Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media, 2011. ISBN: 0387879595, 9780387879598.

Lash TL, Fox MP, MacLehose RF, Maldonado G, McCandless LC, Greenland S. Good practices for quantitative bias analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43(6): 1969–85. PMID: 25080530. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu149.

Alcoholism NIoAAa. Drinking Levels Defined. Available at: http://www.niaaa. nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge- drinking (Accessed July 26, 2015).

Newcomb ME, Clerkin EM, Mustanski B. Sensation seeking moderates the effects of alcohol and drug use prior to sex on sexual risk in young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2011;15(3):565–75. PMID: 20960048. doi: 10. 1007/s10461-010-9832-7.

Baiocchi M, Cheng J, Small DS. Tutorial in biostatistics: Instrumental variable methods for causal inference. Stat Med 2014;33(13):2297–340. PMID: 24599889. doi: 10.1002/sim.6128.

Sturmer T, Wyss R, Glynn RJ, Brookhart MA. Propensity scores for confounder adjustment when assessing the effects of medical interventions using nonexperimental study designs. J Intern Med 2014;275(6):570–80. doi: 10.1111/joim.2014.275.issue-6.

White IR, Carpenter J, Evans S, Schroter S. Eliciting and using expert opinions about dropout bias in randomized controlled trials. Clin Trials 2007;4(2): 125–39. PMID: 17456512. doi: 10.1177/1740774507077849.

McCandless LC, Gustafson P, Levy AR, Richardson S. Hierarchical priors for bias parameters in Bayesian sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding. Stat Med 2012;31(4):383–96. PMID: 22253142. doi: 10.1002/sim.4453.

Greenland S. Multiple-bias modelling for analysis of observational data. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2005; 168:267–306. doi: 10.1111/rssa.2005.168. issue-2.

Darvishian M, Gefenaite G, Turner RM, Pechlivanoglou P, Van der Hoek W, Van den Heuvel ER, et al. After adjusting for bias in meta-analysis seasonal influenza vaccine remains effective in community-dwelling elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67(7):734–44. PMID: 24768004. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014. 02.009.

Luta G, Ford MB, Bondy M, Shields PG, Stamey JD. Bayesian sensitivity analysis methods to evaluate bias due to misclassification and missing data using informative priors and external validation data. Cancer Epidemiol 2013; 37(2):121–26. PMID: 23290580. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.11.006.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Greenland S, Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Sparse data bias: A problem hiding in plain sight. BMJ 2016;352:i1981.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Conflict of Interest: None to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Navadeh, S., Mirzazadeh, A., McFarland, W. et al. Using expert opinion to quantify unmeasured confounding bias parameters. Can J Public Health 107, e43–e48 (2016). https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.107.5240

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.107.5240

Key Words

- Unmeasured confounder

- sensation seeking

- men who have sex with men

- alcohol use

- condomless anal sex

- bias analysis