Vortioxetine is the latest antidepressant approved by the European Medicines Agency (2014). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE ) recommends it for patients who have not responded to two antidepressants within the current episode (NICE 2015), a condition often defined as ‘treatment-resistant depression’ (McIntyre Reference McIntyre, Filteau and Martin2014); however, this recommendation is based on a trial comparing vortioxetine with agomelatine (Montgomery Reference Montgomery, Nielsen and Poulsen2014), indirect evidence from trials in drug-naive patients, and experts’ opinion.

Intriguingly, the mechanism of action of vortioxetine is claimed to be novel and related to the modulation of several serotonin receptors and the inhibition of the serotonin transporter (Sanchez Reference Sanchez, Asin and Artigas2015).

A large number of reviews – almost matching the number of trials of vortioxetine – had been published before the Cochrane review featured in this month's Cochrane Corner (Koesters Reference Koesters, Ostuzzi and Guaiana2017), but these were often flawed by methodological problems, including non-systematic design (i.e. the authors chose to include a subset of trials without defining any specific inclusion/exclusion criteria), the lack of pooled results (i.e. a meta-analysis of the data was not performed, thus it was not possible to draw conclusions on the basis of objective quantitative measures) or conflict of interest (i.e. the drug's manufacturer had funded the review and therefore might have influenced its results). Therefore, the need for a systematic review and meta-analysis with more rigorous methodology was warranted.

Summary of the Cochrane review

The Cochrane review by Koesters et al (Reference Koesters, Ostuzzi and Guaiana2017) included 15 studies involving 7746 adults presenting with a first episode of depression. Vortioxetine was associated with response rates that were better than placebo and similar to serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and with no differences in terms of patients leaving treatment (dropping out).

Definition of the clinical question

The review aimed to assess whether patients with a first episode of depression respond (efficacy) and stay in treatment (acceptability) with vortioxetine more or less than with either placebo or other antidepressants.

The trials’ population of 7746 participants were above 18 years of age and diagnosed with a first episode of depression according to the main international diagnostic criteria. Although patients with comorbid mental illness or suicidal ideation were not excluded a priori, none of the trials included this widely prevalent subgroup. In-patients and out-patients from many countries were considered. Importantly, patients with treatment-resistant depression were excluded.

Any studies using vortioxetine as monotherapy were considered, but those employing doses below the lowest effective dose of 5 mg/day were excluded. The comparison arms included placebo (14 studies) and SNRIs (8 studies). The review did not identify any trial (Box 1) comparing vortioxetine with classes of antidepressant (notably SSRIs) apart from SNRIs.

BOX 1 ‘Empty reviews’

When a literature search for a systematic review retrieves no results, this is called an ‘empty review’. Although this may be related to problems with the search strategy, sometimes an empty search is due to the lack of studies on a specific subject. Publishing an empty review may sound pointless; however, it is now considered important because it can highlight the absence of adequate research in important areas.

The primary outcomes were defined as efficacy, or response to treatment (i.e. a reduction of at least 50% on any depression scale employed), and acceptability, or the number of patients staying in treatment (i.e. the inverse of the number of participants leaving the trial – ‘dropping out’ – for any reason), both measured at 6–8 weeks. Also, several secondary outcomes were measured; for example, drop-outs were divided between those leaving treatment because of inefficacy and those leaving because of adverse events.

Methods

As per best practice when reviewing the effect of treatments, only randomised controlled trials were included.

The search strategy reviewed multiple electronic databases with no restrictions to date, language or publication status. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were reflected by the search terms reported in the article. Then, the reference lists of the articles obtained were screened, and subject experts were contacted for information about ongoing or unpublished studies.

Two review authors independently screened the records for inclusion and, if required, resolved disagreements by consulting a third author. The whole process was appropriately reported in a flow diagram. Data regarding the trials’ methods, population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and funding or notable conflict of interest were extracted.

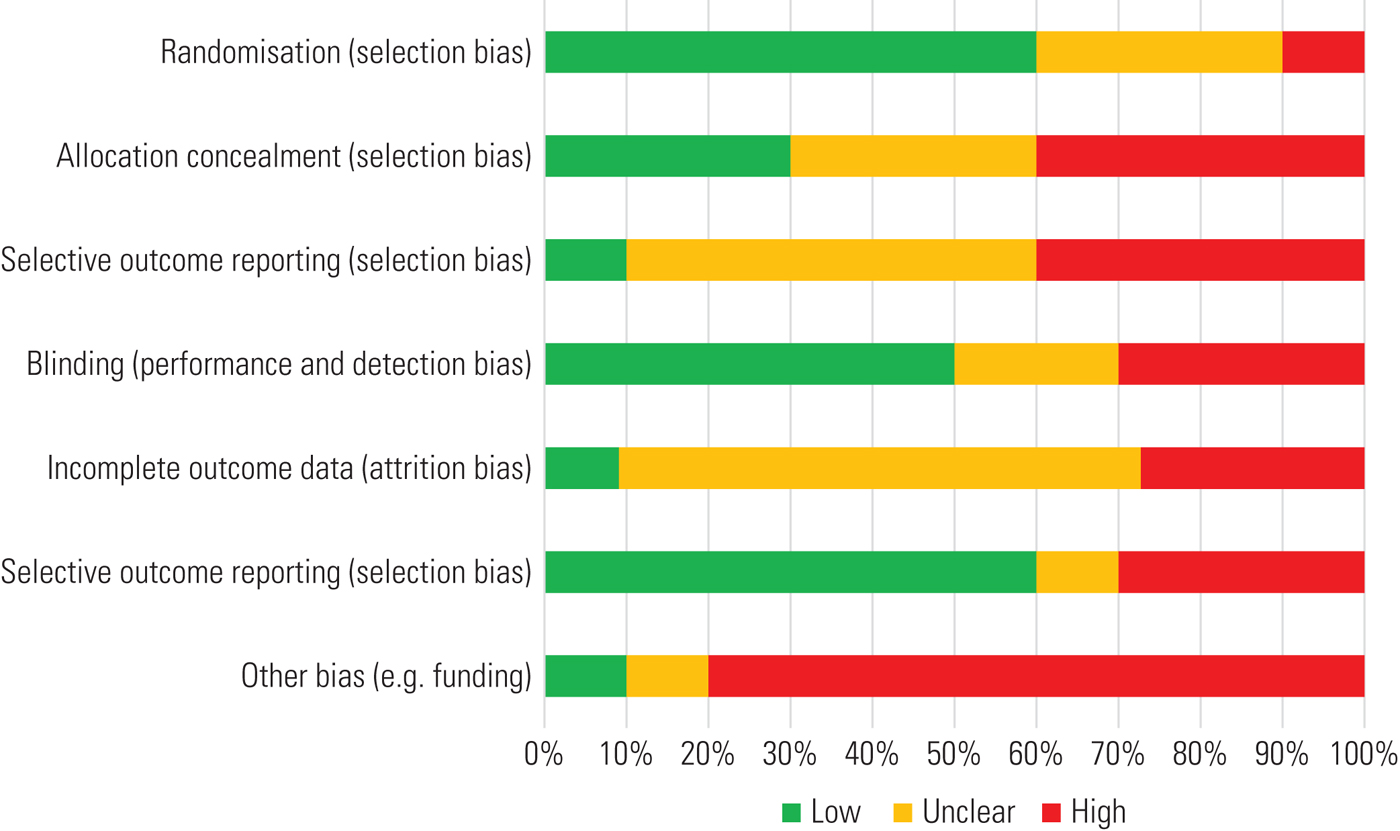

Likewise, the risk of bias was independently assessed by two authors, and reviewed with a third author if necessary, using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions criteria. Trials’ biases were evaluated for randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding (masking), completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting and funding. All of the included trials had an ‘unclear’ risk of bias (Box 2 and Fig. 1) in at least two areas: first, and remarkably, all studies were funded by vortioxetine's manufacturer; the second area varied across the different studies and included selection, performance, detection and attrition biases.

BOX 2 ‘Unclear’ risk of bias

Usually indicated by the amber colour, studies at ‘unclear’ risk of bias sit between those at ‘high’ (red colour) and ‘low’ (green colour) risk of bias. The risk of bias may be unclear either because there are not enough details to differentiate between a ‘high’ and a ‘low’ risk, or because the risk remains unknown despite sufficient information being provided by the study authors.

FIG 1 An example of a risk of bias chart (it does not refer to the study commented on here). The colour coding follows that described in Box 2.

The statistical analysis of data used risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to measure effect sizes.

Results

Vortioxetine proved better than placebo in terms of response (RR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.22–1.49) and was not different for the number of patients staying in treatment (RR = 1.05, 95% CI 0.93–1.19). However, more patients dropped out of vortioxetine treatment because of any adverse events (RR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.09–1.81), whereas more people left the placebo arms because of inefficacy (RR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.34–0.90).

In terms of the quality of the evidence, one-third of the studies showed a drop-out rate above 20%, which negatively affected the significance of all the findings. Besides, the results for the efficacy outcome were very heterogeneous, so the quality of this finding was further downgraded. The review authors did not comment on the precision of their pooled results, but the CIs were not particularly wide.

Overall, the clinical significance of these efficacy results remains uncertain. Although some authors maintain that all statistically significant differences in response rates are also clinically relevant (Montgomery Reference Montgomery and Moller2009), this topic remains a matter of debate. The review authors calculated that the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) (Box 3) was 8 (95% CI 5–12), meaning that a clinician would need to treat eight patients with vortioxetine rather than placebo in order to see one additional patient responding to therapy.

BOX 3 The NNTB and NNTH

The ‘number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome’ (NNTB) is the same as the ‘number needed to treat’ (NNT), defining the expected number of people who need to receive the intervention rather than the comparison for one additional person to develop the outcome over a given period.

The term NNTB has come to replace NNT because of the opposite of the NNT – the ‘number needed to harm’ (NNH). ‘Number needed to harm’ was considered an unpleasant and misleading term, so the wording for the NNH was changed to ‘number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome’ (NNTH), and consequently the NNT was renamed the NNTB.

Turning to studies comparing vortioxetine with other antidepressants, in this instance only SNRIs, vortioxetine was equivalent to SNRIs in efficacy (RR = 0.91, 95% CI 0.82–1.00), acceptability (RR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.73–1.08), and drop-out because of adverse events (RR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.51–1.08) or inefficacy (RR = 1.52, 95% CI 0.70–3.30). In this case, however, the quality of the evidence was extremely low because two-thirds of the included studies showed a drop-out rate above 20%, heterogeneity was high and the CIs were very large and therefore imprecise. Hence, the clinical significance of these findings is difficult to interpret because of the very poor quality of the evidence supporting them.

Discussion

In summary, this review showed that vortioxetine is better than placebo and equal to SNRIs in terms of efficacy, and no worse than either in terms of acceptability. However, there are some important limitations.

First, the trials’ population only included patients who did not have any psychiatric comorbidity or suicidal thoughts andhad not been previously treated with antidepressants. This seems to be far from everyday clinical practice; hence, the external validity of the findings appears limited.

Second, the most commonly prescribed first-line pharmacological treatment for depression, namely SSRIs, are already known to have higher efficacy and acceptability than placebo in a primary care setting (Linde Reference Linde, Kriston and Rücker2015). However, no studies comparing vortioxetine with SSRIs could be identified – a clear limitation to the applicability of this review's evidence.

Third, most clinicians would argue that patients referred to specialist psychiatric services have probably not responded to one or more antidepressants beforehand, but this review excluded trials on treatment-resistant depression, further limiting the applicability of its results. Interestingly, the search strategy identified only one study of patients with treatment-resistant depression, comparing vortioxetine with agomelatine (Montgomery Reference Montgomery, Nielsen and Poulsen2014); yet again the clinical relevance of such comparison is poor for UK practice, as agomelatine is scarcely used (NICE 2015).

Conclusions

Overall, it is questionable whether this study can influence clinical practice in the UK; however, it has highlighted some key questions that research needs to explore further, namely whether vortioxetine is better than SSRIs and whether vortioxetine is useful in treatment-resistant depression.

Meanwhile, new evidence has been made available since the publication of this review. The most recent and largest network meta-analysis (currently considered at the top of the evidence-base hierarchy) of antidepressants in adults identified an odds ratio (OR) for efficacy of 1.66 (95% CI 1.45–1.92) and for acceptability of 1.01 (95% CI 0.86–1.19) when vortioxetine was compared with other antidepressants (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Furukawa and Salanti2018).

Taking a different perspective, another recent review (McIntyre Reference McIntyre2017) highlighted that vortioxetine has very low rates of side-effects commonly described for SSRIs – such as sexual dysfunction, weight gain and discontinuation effects – with nausea being the only adverse event reported by >10% of patients; moreover, vortioxetine was shown to prevent depressive relapses while remaining well-tolerated as long-term therapy. Patients frequently consider their overall functioning more important than symptom relief (Saltiel Reference Saltiel and Silvershein2015). In this regard, manufacturers claimed that vortioxetine improves cognition and social relationships independently of mood scores (Lundbeck 2016), but the former have not been measured in this Cochrane review.

Overseas, the 2016 Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments guidelines for depression included vortioxetine among first-line pharmacological treatments (Kennedy Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre2016). Notably, the UK's NICE guidelines on vortioxetine (NICE 2015) are due to be updated by the end of 2018 and therefore are not available at the time of writing this commentary; however, they may reflect some of the additional findings reported here.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Kate Saunders, Professor Andrea Cipriani and Professor John Geddes (University of Oxford, Department of Psychiatry) for their advice on this project. The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Wellcome Trust or the National Health Service.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.