Abstract

Carbon-based adsorbent is considered to be one of the most promising adsorbents for CO2 capture form flue gases. In this study, a series of N-doped microporous carbon materials were synthesized from low cost and widely available urea formaldehyde resin co-polymerized with furfuralcohol. These N-doped microporous carbons showed tunable surface area in the range of 416–2273 m2 g−1 with narrow pore size distribution within less than 1 nm and a high density of the basic N functional groups (2.93–13.92 %). Compared with the carbon obtained from urea resin, the addition of furfuralcohol apparently changed the surface chemical composition and pore size distribution, especially ultramicropores as can be deduced from the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR), and pore size distribution measurements and led to remarkable improvement on CO2 adsorption capacity. At 1 atm, N-doped carbons activated at 600 °C with KOH/UFFC weight ratio of 2 (UFFA-2-600) showed the highest CO2 uptake of 3.76 and 1.57 mmol g−1 at 25 and 75 °C, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Carbon dioxide as the main contributor to global warming has attracted extensive attention worldwide. The reduction or elimination of CO2 emission into the atmosphere is extremely urgent. Therefore, carbon capture and storage (CCS) has been a research hotspot in recent years. Among various technologies for CCS, adsorption is considered to be one of the most promising techniques in practical application due to low energy consumption and mild operating conditions compared to solvent absorption, membrane systems, and cryogenic fractionation [1]. It is possible to reach the goal of the US Department of Energy (DOE) to develop a fossil fuel conversion system capable of capturing 90 % of the produced CO2 that increases the total costs by less than 10 % [2]. However, high adsorption capacity, high CO2/N2 selectivity, and outstanding cycling performance are the key essentials for pressure-swing adsorption or temperature-swing adsorption technology [3]. In this context, zeolites [4], porous carbons [5], porous silicas [6], BCN graphene analogues [7], porous organic polymers [8], MOFs [9, 10], and COFs [11, 12] have been studied for CO2 adsorption in recent years. Compared with other materials, carbonaceous adsorbent possesses unique superiority in terms of capture capacity and selectivity due to its hydrophobic property, high thermal and chemical stability, tunable pore structure, low cost, and physical adsorption mechanism [13].

Recently, researchers [14–16] have shown that the fine micropores and heteroatom incorporation are the decisive factors, which affect adsorption properties. N-doped carbon material with proper pore structure, owing to the promotion of the interaction between CO2 molecules and carbon surface, is considered to be more efficient for CO2 adsorption than traditional carbon such as commercial activated carbon with low capacity of 0.89 mmol g−1 and low adsorptive selectivity [17]. The CO2 uptake of N-doped carbon material can be enhanced effectively so that it can be close to the minimum working capacity required to match the efficiency of a conventional liquid-phase amine-based system [18]. For example, Lu et al. [16] synthesized N-doped porous carbon monolith with the copolymer of resorcinol, formaldehyde, and lysine as precursor which has shown high CO2 capacity of 3.13 mmol g−1 at 25 °C, 1 atm.

Besides the effect of nitrogen incorporation, the presence of ultramicropores is considered to be another decisive factor. Recently, Presser et al. [19] studied the CO2 uptake on microporous carbon in relation to the pore size and found that the micropores smaller than 1 nm are responsible for high CO2 adsorption at 1 bar. Jaroniec and Wickramaratne [20, 21] obtained phenolic resin-based carbon with unprecedented amount of CO2 (4.6 mmol g−1 at 23 °C), and their study also showed that a higher capacity resulted from a higher pore volume of fine micropores (<0.8 nm). Zhao et al. [22] prepared N-doped carbon material using p-diaminobenzene as precursor and found that furfuralcohol can improve the adsorption effectively, but the mechanism is not elaborated clearly. From our point of view, we are trying to find a method for the fabrication of N-doped carbon material with high CO2 capture capacity from widely provided low-cost raw chemicals. In our previous work, we found that urea formaldehyde resin had good ability to produce carbon material with high CO2 capture capacity [23]. Then, we expanded our strategy to urea furfural resin polymerized from urea and furfural, which also showed high CO2 adsorption capacity [24]. However, the carbon source of furfural is not very widely provided as formaldehyde. Here, in this study, for the purpose of further improving the CO2 adsorption capacity, furfuralcohol was chosen to form a copolymer with urea and formaldehyde and treated by the same carbonization-activation process to make porous carbon. The samples co-polymerized with furfuralcohol showed remarkable improvement of CO2 adsorption capacity mainly due to the development of fine micropores, even though they possess comparable specific surface area (about 1000 m2/g) and lower nitrogen content, suggesting that the fine micropores, especially ultramicropores, play a more important role in enhancing the CO2 adsorption capacity of adsorbents.

Method

Materials Preparation

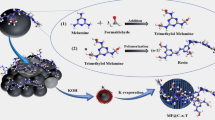

The samples were prepared by a two-step method. For a typical preparation, 3.0-g urea was added to 4.1 g formaldehyde solution and stirred for 0.5 h, then a certain amount of furfuralcohol (furfuralcohol/urea at a weight of 0, 1, 1.5, and 2) was added to the solution and stirred for 1 h, and then polymerized at 373 K for 24 h. The obtained furfural resin (UFF) was carbonized at 873 K for 4 h under a N2 flow of 50 ml min−1. The carbonized sample (denoted as UFFC) was chemically activated with KOH (KOH/UFFC at a weight ratio of 1 to 4) at several temperatures in the range of 500–800 °C with a ramping rate of 5 °C min−1 under N2 flow of 50 ml min−1 and maintained for 1 h. The obtained material was washed with excess amounts of 1 M HCl aqueous solution followed by deionized water till a neutral pH. Finally, the samples were dried in air at 100 °C for 12 h. The activated carbon was denoted as UFFAa-x-y, where a represents the furfuralcohol/urea weight ratio and be omitted when furfuralcohol/urea weight ratio is 1.5, and x and y represent the KOH/UFFC weight ratio and activation temperature, respectively.

Materials Characterization

The morphologies of the materials were examined by scanning electron microcopy (SEM) using a HITACHI S-4800 and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a JEOL JEM-2100UHR transmission electron microscope. X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded in the range of 2θ = 10°–80° on a PANalytical X’Pert PRO MPD, using a Cu-Kα monochromated radiation source and a Ni filter. The nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms were measured at −196 °C using a Micromeritics Tristar 3000 apparatus. Prior to measurement, the samples were degassed in vacuum at 300 °C for at least 3 h. The total specific surface area was calculated using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method (p/p o = 0.05–0.25), and the microporous surface area was calculated by the t-Plot method. Narrow micropore distribution was analyzed on Micromeritics ASAP 2020. The micropore distributions were calculated via the Horvath-Kawazoe (HK) method. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were obtained on a Nicolet Fourier spectrophotometer, using the KBr pellet technique. The contents of C, H, and N were determined by using a Vario EL III CHNS/O elemental analyzer. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out in a UHV system using a monochromated Al Kα radiation (hν = 1486.6 eV) and an Omicron Sphera II hemispherical electron energy analyzer.

CO2 Capture Measurements

CO2 adsorption was performed on Micromeritics Tristar 3000 apparatus at different temperatures (25 and 75 °C). Prior to the analysis, the samples were degassed at 300 °C in vacuum for 4 h. The adsorption capacity was investigated by exposing quantitative amount of CO2 with a concentration of 99.99 % and calculated in terms of adsorbed amount per gram of sample in the pressure range between 0.001 and 1 atm.

Results and Discussion

Structural Characterization

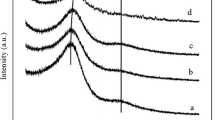

In our previous work [23, 24], as well as the previously reported literature [25], it has been demonstrated that the carbonization-activation process played an important role in controlling the nitrogen content and pore structure of the material. Here, two batches of porous carbon materials with different activation temperatures and amounts of KOH addition were synthesized, and their wide angle XRD patterns are shown in Fig. 1. All samples exhibit a broad diffraction peak at about 25.8°, which can be assigned to diffraction from (002) corresponding to d spacing of 3.42 Å. This indicates turbostratic ordering of the atoms in the graphene layers of the samples [26]. With the increase of the activation temperature or the amount of KOH, the intensity of (002) reflection decreases noticeably, indicating that a higher activation temperature or excess KOH could destroy the graphite-like structure. The structure of the sample appears to be more sensitive to the activation temperature. No obvious diffraction peak can be detected when the sample was activated at 800 °C (UFFA-2-800 in Fig. 1a), which demonstrates that amorphous carbons were obtained. Additionally, compared to the sample without furfuralcohol addition (UFC), the diffraction peaks of UFFC samples shift slightly to low-angle region, which demonstrates that the interlayer d spacing gets larger. This phenomenon may have resulted from the disordering induced by the addition of furfuralcohol, which may benefit the formation of micropores during the activation process.

In order to investigate the textural properties, the samples were characterized by the nitrogen adsorption-desorption analysis. The isotherms of the obtained materials at different activation temperatures and different amounts of KOH are displayed in Fig. 2. All isotherms are typical type I isotherms with significant N2 uptake at low relative pressure (P/P O < 0.1) and an adsorption plateau at higher relative pressure. All these features confirm that the obtained materials are highly microporous except for UFFA-2-500. The sample activated at 500 °C showed an extremely low specific surface area as 28 m2 g−1, which indicates that the sample was lack of activation at such low temperature. Actually, the sample before activation (UFFC) showed even much lower specific surface area (0.2 m2 g−1) than UFFA-2-500. After the activation temperature increased up to 600 °C, the specific surface area increased remarkably, which means that chemical reaction of KOH with raw carbon material was accelerated. Furthermore, no hysteresis loops are present, which indicates that no mesopores are present in the materials. Compared with UFA-2-600, the sample UFFA-2-600 obtained from the same carbonization and activation treatment showed almost the same N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms indicating a comparable Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area and pore volume (1055 m2 g−1 and 1093 m2 g−1 with the same pore volume of 0.58 cm3 g−1, Table 1), and the samples carbonized with different furfuralcohol dosages also showed comparable BET surface area and pore volume indicating that the impact of furfuralcohol on the total surface area and pore volume is not significant. However, the microporous specific surface area and microporous pore volume of UFFA-2-600 is much higher than that of the sample without furfuralcohol addition (955 m2 g−1 and 0.49 cm3 g−1 versus 861 m2 g−1 and 0.45 cm3 g−1, Table 1). Moreover, the features of isotherms are changed with different activation temperatures and amounts of KOH indicating changes of the surface area and pore structures. With the increase of the activation temperature and KOH dosage, the surface area and pore volume increased significantly from 416 to 2273 m2 g−1 and 0.23 to 1.24 cm3 g−1, respectively (Table 1). It is worth noting that most of the pore volume can be ascribed to micropore volume, which confirms that the micropores are dominant. The sample prepared under mild activating condition (UFFA-2-600) possesses the highest proportion of micropore volume (0.49 cm3 g−1/0.58 cm3 g−1). Further increase of the activation temperature (UFFA-2-800) or KOH dosage (UFFA-4-600) led to a decrease of the proportion of micropore volume. This result indicates that the activation process can not only lead to high porosity but also affects the pore structure.

N2 isotherms and micropore distributions of typical samples. a Samples activated at different temperatures (black square UFA-2-600, red circle UFFA-2-500, blue up-triangle UFFA-2-600, dark cyan down-triangle UFFA-2-700, magenta left-triangle UFFA-2-800). b Samples activated with different amounts of KOH (black square UFFA-1-600, red circle UFFA-2-600, blue up-triangle UFFA-3-600, dark cyan down-triangle UFFA-4-600). c Micropore distribution of typical samples investigated by N2 adsorption at low relative pressure of below 0.03 (black square UFA-2-600, red circle UFFA-1-600, blue up-triangle UFFA-2-600, dark cyan down-triangle UFFA-2-800)

The narrow pore size distribution of selected samples was further investigated by N2 adsorption at low relative pressure of below 0.03, which is shown in Fig. 2c. It should be noted that the samples carbonized with furfuralcohol and activated in mild conditions generated much more micropores centered at around 0.6 nm than UFA-600. Additionally, the pore size is highly dependent on activated conditions with an obvious enlargement of the pore size. The sample activated at 800 °C possessed enlarged micropores of about 0.9 nm and a broadening of the pore size distribution. This pore enlargement is probably due to the over-activation at higher temperature and is consistent with aforementioned results [23], as well as the literature reported [27].

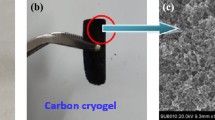

In order to reveal the morphology of the samples, scanning electron microcopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were used and the morphology of the obtained materials is shown in Fig. 3. UFFC before activation possessed 3-D net shape of macroporous structure as shown in Fig. 3a, which may have been inherited from the morphology of the furfural resin, and is benefited by mixing with KOH during activation. In contrast, the sample prepared without furfuralcohol (UFC) displays bulk morphology with no obvious mesopores or macropores (Fig. 3c). Both of the TEM images demonstrate that some worm-like micropores were formed by stacking of curved graphene in the carbonized samples (UFC and UFFC). These considerably fine micropores cannot be characterized by N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms due to the ultrafine nature. After activation, it can be observed from the SEM image that the 3-D net shape of macroporous structure was preserved (Fig. 3b), but the bulk morphology gets spongier. Many more micropores were also formed during the activation process. It is postulated that the micro-macro hierarchical pore structure should benefit CO2 adsorption and desorption due to reduced mass transfer resistance.

Chemical Properties

The chemical compositions of the obtained samples are listed in Table 1, and it can be seen that higher nitrogen content was still retained even after activating under severe conditions. In contrast to UFA, the nitrogen content of the UFFA samples with furfuralcohol addition was decreased due to higher proportion of carbon source of the precursor. Interestingly, an increase in the nitrogen content is observed with the increase of the dosage of furfuralcohol, from 7.29 to 8.46 %. One possibility is that KOH prefers etching the fragments carbonized from furfuralcohol to that from urea resin, and the nitrogen atoms are protected during the activation process resulting from different surface charge densities [22]. What is noteworthy is that the insertion of O atoms into the framework occurs during the activation process resulting in the increase of the oxygen content. It is well known that the increase of the activation temperature or the dosage of KOH leads to the release of nitrogen in the form of molecular N2, HCN, or other gases [28], which is responsible for the decreased of nitrogen content. However, the release of nitrogen reduces the affinity of the samples to CO2 molecule and this can be confirmed by the CO2 adsorption capacity and the isosteric heat of adsorption, which will be elaborated latter.

The previous researches [13, 29, 30] demonstrated that the N-containing functional groups are closely related to the CO2 adsorption capacity of the adsorbent. Accordingly, the presence of nitrogen functionalities in these as-synthesized carbon materials was investigated by means of FT-IR. Figure 4 shows the FT-IR spectra of the samples with different activation temperatures and KOH dosages. The bands of the activated samples get broader and overlap due to the strong adsorption of carbons. Notably, the sample UFA-2-600 possesses similar bands with only slight intensity differences to the samples prepared with furfuralcohol addition, demonstrating that the addition of furfuralcohol did not change the surface chemical property significantly. Generally, all the activated samples exhibit two medium bands at around 1590 and 1250 cm−1, which can be assigned to C═C stretching vibrations in aromatic rings and C–N stretching vibrations, respectively. Two bands at ca. 2940 and 2828 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibration of methylene and the peak at 3410 cm−1 corresponds to the N–H or O–H symmetric stretching vibration [16]. Three sharp bands are also detected at 1080, 1039, and 875 cm−1, respectively, which might be assigned to asymmetric stretching vibration of the ether, C–O stretch of C–OH, and cyclic ether linkages, respectively. All of the FT-IR analysis results confirm the existence of C–N and C–O species in the obtained materials. In addition, the intensity of the band at 1250 cm−1 decreased with the increase of the activation. The band of UFFA-2-800 at 1250 cm−1 almost disappears when activated at 800 °C, demonstrating that the nitrogen atoms were gradually removed. This result is also confirmed by the elemental analysis.

The nature of nitrogen species was further investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). In Fig. 5, the fitting of N1s peak gives the binding energies of 398, 399, 400, 401, and 403 eV, which can be attributed to pyridinic-N, -C═NH or PhNH2, pyrrolic-N, quaternary-N, and oxidized-N [31], respectively. The peak assignment reveals that the nitrogen species evolution occurred before and after activation as well as by the addition of furfuralcohol. As shown in Table 2, much more nitrogen species in UFFC are in the form of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds (pyridinic/pyrrolic-N and quaternary-N) than those in UFC (90 to 79.8 %), which is obviously induced by the addition of furfuralcohol. This result confirms our inference that nitrogen species are in more stable heterocyclic form when carbonized with furfuralcohol. After the carbon being activated, a significant increase of quaternary-N was observed, which was mainly transformed from pyridinic-N, -C═NH or PhNH2, and pyrrolic-N. The total N content of the surface also presents obvious decrease due to activation process, which is also in accordance with the results of FT-IR and elemental analysis.

CO2 Adsorption Performance

The adsorption capacities of the different materials were measured at 25 and 75 °C under atmospheric pressure (Fig. 6). The measured adsorption capacities correspond to those expected from their structures and chemical properties. However, the UFFC showed extraordinary uptake of up to 1.66 mmol g−1 (Table 3), which is one of the best values reported for carbon-based adsorbents with poor pore structure. In addition, it can be observed that the sample prepared with furfuralcohol (UFFA-2-600) showed an enhanced adsorption capacity compared with UFA-2-600 (3.76 to 3.21 mmol g−1). For the samples obtained at different activation conditions, as can be seen in Table 3, the CO2 uptakes are in the range of 1.8–3.76 mmol g−1 at 25 °C. At a higher temperature of 75 °C, the CO2 molecules have higher energy and, hence, can escape from the surface easily. Therefore, the CO2 uptakes of the samples are much lower (1.00–1.57 mmol g−1) at 75 °C. With the increase of the activation temperature or KOH dosage, the adsorption capacities increased first and then decreased as expected. The sample UFFA-2-600 with high proportion of fine micropore volume and moderate BET surface area showed the highest uptake of about 3.76 mmol g−1 at 25 °C, 1 bar. The lower CO2 uptakes of the samples activated at mildest conditions (UFFA-2-500 and UFFA-1-600) can be attributed to the lack of activation resulting in poor pore structure. Notably, the sample UFFA-1-600 showed higher CO2 uptake than those of UFFA-3-600 and UFFA-4-600 at low pressure (<0.15 bar) although it has poor pore structure, which suggests that the mild activation condition is in favor of the low pressure adsorption. Apparently, there is no obvious relationship between the CO2 adsorption capacity and the BET surface area or total pore volume. For instance, the sample UFFA-2-600 showed higher uptake than UFA-2-600, although they have comparable BET surface area and total pore volume.

To determine the effect of the incorporation of nitrogen and the porosity in promoting the adsorption of CO2, CO2 uptakes have been normalized by micropore volume and N content as shown in Table 4. The uptake per micropore volume decreased when the activation conditions were more severe. For example, the samples UFFA-2-700 and UFFA-2-800 showed high total pore volume but low CO2 uptake per micropore volume, indicating that the severe activation conditions have negative effects on the adsorption of CO2. However, UFFA-1-600 with low micropore volume showed higher CO2 uptake per micropore volume confirming a stronger affinity for CO2 molecules, which suggests that the chemical adsorption plays a more important role in enhancing the adsorption of CO2. On the contrary, CO2 uptakes per millimoles of nitrogen increase with the activation conditions getting more severe. The samples UFFA-2-700 and UFFA-2-800 with well-developed pore structure showed much higher CO2 uptakes per millimoles of nitrogen, indicating that the adsorption of CO2 on these adsorbents is mainly physical adsorption [32]. However, the UFA-2-600 and UFFA-2-600 samples with comparable CO2 uptakes per micropore volume showed different CO2 uptakes per millimoles of nitrogen. The sample UFFA-2-600 showed double the CO2 uptake per millimoles of nitrogen indicating that its pore structure is more beneficial to CO2 adsorption.

The above discussion confirms that CO2 adsorption performance of the nitrogen-doped carbon adsorbents is the combination of physical adsorption and chemical adsorption, but the roles they play vary with the changes of pore structures and N contents. As demonstrated in the literatures [33], the physical adsorption mainly occurs in the fine micropores and it could be well described by micropore filling mechanism, especially in ultramicropores (the average pore diameter of ultramicropores is less than 0.7 nm as defined by IUPAC) [34]. The high ultramicropore volume of UFFA-2-600 (0.2 cm3 g−1) compared with that of UFA-2-600 (0.14 cm3 g−1) as presented in Fig. 7a is the main reason for the higher CO2 uptake in the former. This can also explain the CO2 adsorption of the various samples activated at different temperatures or different amounts of KOH. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the micropore volume of UFFA-2-800 is about 0.13 cm3 g−1 which is much lower than that of UFFA-2-600, resulting in the lower CO2 uptake by the former. As shown in the schematic diagram (Fig. 7b), the CO2 molecule with a radius of about 0.33 nm can only be filled in the pores by no more than two layers because of their small pore diameter. However, the adsorbed CO2 molecules can get condensed and packed in the pores due to the superposition of van der Waals forces given by the two walls because of the small pore diameter of the pores. Based on this view, the CO2 uptake is postulated to be closely related to the ultramicropore volume.

The nitrogen atoms in the pore walls can enhance the effect between the wall and CO2 molecule undoubtedly although the mechanism needs further investigation [27, 35, 36]. The high N content and plentiful basic groups is another essential reason for the higher CO2 uptake of UFFAs. But as can be seen in Fig. 8a, there is no obvious relationship between the CO2 uptake and N content. To further illustrate the effect of nitrogen doping in enhancing the affinity of pore wall, the isosteric heats of adsorption are calculated from the CO2 adsorption isotherms at 25 and 75 °C by using the Clausius-Clapeyron equation [37–41]. As can be seen in Fig. 8b, the effect of N doping is reflected by the isosteric heat of adsorption and the isosteric heat of adsorption decreased with the decrease of nitrogen content due to the increase of activation temperature as elaborated above (UFFA-2-600 versus UFFA-2-700). However, the effect of nitrogen in enhancing the capacity is restricted. The sample UFA-2-600 has a lower CO2 uptake than that of UFFA-2-600 though it possesses much higher N content (13.92 to 8.03 %). This may be because there is no more space for CO2 molecule to be occupied due to the fact that the adsorbed CO2 molecules have been packed closely in the ultramicropores as previously described (according to the D-A theory, the CO2 molecules fill the micropores in a liquid-like state). The groups containing nitrogen atoms just enhance the interaction between the surface of the adsorbents and CO2 molecules, possessing higher adsorption isosteric heat, while the capacity is based on the combination of pore structure and nitrogen content. This may be the main reason why the isosteric heat of adsorption relies on the nitrogen content, but there is no obvious relationship between nitrogen content and adsorption capacity.

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated a feasible and very simple method for the synthesis of N-doped microporous carbon via a carbonization-activation process by using urea formaldehyde resin co-polymerized with furfuralcohol, which showed tunable surface area and high nitrogen content. N-doped microporous carbon with a high surface area of about 1093 m2 g−1 and a high density of N functional groups (8.03 %) was obtained. Furfuralcohol plays an important role in improving the pore structure of the adsorbent. More ultramicropores of about 0.6 nm were formed in the above microporous carbon, which is a decisive factor for the CO2 adsorption uptake. We also found that much more nitrogen species in the carbonized samples are in the form of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds. The obtained samples showed excellent CO2 adsorption uptake in the range of 1.8–3.76 mmol g−1 and 1.00–1.57 mmol g−1 at 25 and 75 °C, respectively, confirming the combination of physical and chemical adsorption mechanism on CO2 adsorption capacity improvement. In addition, this reaction system can be further improved using other carbon sources.

Reference

Siriwardane RV, Shen MS, Fisher EP, Poston JA. Adsorption of CO2 on molecular sieves and activated carbon. Energy Fuels. 2001;15:279–84.

DOE/NETL. Carbon dioxide capture and storage RD&D roadmap, U.S. Department of Energy. 2010. http://www.netl.doe.gov/File%20Library/Research/Carbon%20Seq/Reference%20Shelf/CCSRoadmap.pdf

D’Alessandro DM, Smit B, Long JR. Carbon dioxide capture: prospects for new materials. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:6058–82.

Siriwardane RV, Shen M, Fisher EP. Adsorption of CO2 on zeolites at moderate temperatures. Energy Fuels. 2005;19(3):1153–9.

Sevilla M, Fuertes AB. Sustainable porous carbons with a superior performance for CO2 capture. Energy Environ Sci. 2011;4:1765–71.

Serna-Guerrero R, Dana E, Sayari A. New insights into the interactions of CO2 with amine-functionalized silica. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2008;47:9406–12.

Raidongia K, Nag A, Hembram KPSS, Waghmare UV, Datta R, Rao CNR. BCN: a graphene analogue with remarkable adsorptive properties. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:149–57.

Modak A, Nandi M, Mondal J, Bhaumik A. Porphyrin based porous organic polymers: novel synthetic strategy and exceptionally high CO2 adsorption capacity. Chem Commun. 2012;48:248–50.

Wang B, Cote AP, Furukawa H, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Colossal cages in zeolitic imidazolate frameworks as selective carbon dioxide reservoirs. Nature. 2008;453:207–11.

Li JR, Ma Y, McCarthy MC, Sculley J, Yu J, Jeong HK, et al. Carbon dioxide capture-related gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Coord Chem Rev. 2011;255:1791–823.

Mohanty P, Kull LD, Landskron K. Porous covalent electron-rich organonitridic frameworks as highly selective sorbents for methane and carbon dioxide. Nat Commun. 2011;2:401.

Patel HA, Karadas F, Canlier A, Park J, Deniz E, Jung Y, et al. High capacity carbon dioxide adsorption by inexpensive covalent organic polymers. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:8431–37.

Sevilla M, Valle-Vigón P, Fuertes AB. N-doped polypyrrole-based porous carbons for CO2 capture. Adv Funct Mater. 2011;21(14):2781–7.

Arenillas A, Smith KM, Drage TC, Snape CE. CO2 capture using some fly ash-derived carbon materials. Fuel. 2005;84:2204–10.

Xing W, Liu C, Zhou ZY, Zhou J, Wang GQ, Zhuo SP et al. Oxygen-containing functional group-facilitated CO2 capture by carbide-derived carbons. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2014;9:189.

Hao G, Li W, Qian D, Lu A. Rapid synthesis of nitrogen-doped porous carbon monolith for CO2 capture. Adv Mater. 2010;22:853–7.

Maroto-Valer MM, Tang Z, Zhang Y. CO2 capture by activated and impregnated anthracites. Fuel Process Technol. 2005;86:1487–502.

Gray ML, Champagne KJ, Fauth D, Baltrus JP, Pennline H. Performance of immobilized tertiary amine solid sorbents for the capture of carbon dioxide. Int J Greenhouse Gas Control. 2008;2:3–8.

Presser V, McDonough J, Yeon S, Gogotsi Y. Effect of pore size on carbon dioxide sorption by carbide derived carbon. Energy Environ Sci. 2011;4:3059–66.

Wickramaratne NP, Jaroniec M. Importance of small micropores in CO2 capture by phenolic resin-based activated carbon spheres. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1:112–6.

Wickramaratne NP, Jaroniec M. Activated carbon spheres for CO2 adsorption. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:1849–55.

Zhao Y, Zhao L, Yao K, Yang Y, Zhang Q, Han Y. Novel porous carbon materials with ultrahigh nitrogen contents for selective CO2 capture. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:19726–31.

Liu Z, Du Z, Song H, Wang C, Subhan F, Xing W, et al. The fabrication of porous N-doped carbon from widely available urea formaldehyde resin for carbon dioxide adsorption. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2014;416:124–32.

Liu Z, Du Z, Xing W, Yan Z. Facial synthesis of N-doped microporous carbon derived from urea furfural resin with high CO2 capture capacity. Mater Lett. 2014;117:273–5.

Hou PX, Orikasa H, Yamazaki T, Matsuoka K, Tomita A, Setoyama N, et al. Synthesis of nitrogen-containing microporous carbon with a highly ordered structure and effect of nitrogen doping on H2O adsorption. Chem Mater. 2005;17:5187–93.

Vinu A, Ariga K, Mori T, Nakanishi T, Hishita S, Golberg D, et al. Preparation and characterization of well-ordered hexagonal mesoporous carbon nitride. Adv Mater. 2005;17(13):1648–52.

Xing W, Liu C, Zhou Z, Zhang L, Zhou J, Zhuo S, et al. Superior CO2 uptake of N-doped activated carbon through hydrogen-bonding interaction. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5(6):7323–7.

Nandi M, Okada K, Dutta A, Bhaumik A, Maruyama J, Derks D, et al. Unprecedented CO2 uptake over highly porous N-doped activated carbon monoliths prepared by physical activation. Chem Commun. 2012;48:10283–5.

Drage TC, Arenillas A, Smith KM, Pevida C, Piippo S, Snape CE. Preparation of carbon dioxide adsorbents from the chemical activation of urea–formaldehyde and melamine–formaldehyde resins. Fuel. 2007;86:22–31.

Zhang ZJ, Xu MY, Wang HH, Li Z. Enhancement of CO2 adsorption on high surface area activated carbon modified by N2, H2 and ammonia. Chem Eng J. 2010;160:571–7.

Zhang Z, Zhou J, Xing W, Xue Q, Yan Z, Zhuo S, et al. Critical role of small micropores in high CO2 uptake. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2013;15:2523–9.

Liu L, Deng QF, Ma TY, Lin XZ, Hou XX, Liu YP, et al. Ordered mesoporous carbons: citric acid-catalyzed synthesis, nitrogen doping and CO2 capture. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:16001–9.

Hu X, Radosz M, Cychosz KA, Thommes M. CO2-filling capacity and selectivity of carbon nanopores: synthesis, texture, and pore-size distribution from quenched-solid density functional theory (QSDFT). Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:7068–74.

Sing KSW, Everett DH, Haul RAW, Moscou L, Pierotti RA, Rouquerol J, et al. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems. Handbook of heterogeneous catalysis. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2008.

Wang L, Yang RT. Significantly increased CO2 adsorption performance of nanostructured templated carbon by tuning surface area and nitrogen doping. J Phys Chem C. 2012;116:1099–106.

Vaidhyanathan R, Iremonger SS, Shimizu GK, Boyd PG, Alavi S, Woo TK. Direct observation and quantification of CO2 binding within an amine-functionalized nanoporous solid. Science. 2010;330:650–3.

Saleh M, Tiwari JN, Kemp KC, Yousuf M, Kim KS. Highly selective and stable carbon dioxide uptake in polyindole-derived microporous carbon materials. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(10):5467–73.

Zhao Y, Liu X, Yao K, Zhao L, Han Y. Superior capture of CO2 achieved by introducing extra-framework cations into N-doped microporous carbon. Chem Mater. 2012;24:4725–34.

Zhou H, Xu S, Su H, Wang M, Qiao W, Ling L, et al. Facile preparation and ultra-microporous structure of melamine–resorcinol–formaldehyde polymeric microspheres. Chem Commun. 2013;49:3763–5.

Wang J, Senkovska I, Oschatz M, Lohe MR, Borchard L, Heerwig A, et al. Imine-linked polymer-derived nitrogen-doped microporous carbons with excellent CO2 capture properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5(8):3160–7.

Gu JM, Kim WS, Hwang YK, Huh S. Template-free synthesis of N-doped porous carbons and their gas sorption properties. Carbon. 2013;56:208–17.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation China (U1362202 and 21206196), Innovation Foundation of CNPC (2013D-5006-0404 and 2014D-5006-0404), and China Scholarship Council (CSC No. 201406455026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

ZL and ZD generated the research idea and designed the experiments. YY and ZD carried out the experiments and drafted the manuscript. WX, SK, and ZY revised the manuscript. SK, ZY, DZ, and XG participated in the analysis of data. ZY supervised the whole work and given final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Yang, Y., Du, Z. et al. Furfuralcohol Co-Polymerized Urea Formaldehyde Resin-derived N-Doped Microporous Carbon for CO2 Capture. Nanoscale Res Lett 10, 333 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1041-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1041-x