-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Natasha Chong Cole, Ruopeng An, Soo-Yeun Lee, Sharon M Donovan, Correlates of picky eating and food neophobia in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Nutrition Reviews, Volume 75, Issue 7, July 2017, Pages 516–532, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nux024

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Context: Picky eating behavior is prevalent among toddlers and may negatively impact their growth and development. Objective: This article summarizes the correlates of picky eating and food neophobia in young children, which were identified using a socio-ecological framework. Data Sources: A literature search was conducted in 4 electronic databases. Study Selection: Inclusion criteria were English-language peer-reviewed publications that investigated correlate(s) of picky eating or food neophobia in children aged ≤30 months. Data Extraction: Correlates were categorized into 4 levels: cell, child, clan (family), and community/country. Thirty-two studies, which examined 89 correlates, were identified from the keyword searches of the databases and manual searches of the reference lists of included articles. Results: The most examined correlates were characteristics related to the child (sex, weight, and dietary intake) and parent (feeding beliefs and practices). A meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of picky eating to be 22%. Each additional month of a child’s age was associated with a 0.06 U increase in the Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire food fussiness score. Conclusion: This review highlights the importance of investigating child–parent dyads and bidirectional feeding interactions and draws attention to the lack of picky eating research at the level of the cell and the community/country.

INTRODUCTION

Picky eating is characterized by low dietary variety, unwillingness to eat either familiar or novel foods, and problematic interference with the parent–child relationship.1,2 These behaviors are prevalent in young children—up to one half of toddlers are reported to be picky eaters.3 One longitudinal study showed that the highest incidence of picky eating occurred in children 2 years of age.4 The first 2 years of life are critical in the development of healthy eating habits,5,6 and dietary patterns and food preferences established in early life continue in preschool, school-aged years, and young adulthood.7–9 During infancy and toddlerhood, children develop autonomy, an emerging sense of self (such as self-concept), social competence, and self-regulation.10 Aligning with these developmental changes is the ability to control positive and negative emotions11 and comply with caregivers’ requests.12 Feeding difficulties often emerge in young children as they acquire skills related to gross motor development and self-feeding and transition from a liquid-based diet to foods consumed by the family.5,13 Picky eating behavior may persist later in life,14–18 and additional research is needed to develop a better understanding of the early life factors contributing to picky eating behavior during the transition to an adult diet.

Picky eating can affect children’s nutrition intake and dietary quality and, as a consequence, negatively impact their growth and development.19,20 Studies have also shown associations between picky eating and risk of depression,21 eating disorders,15 and emotional and behavioral problems.22 Although picky eating behavior has been hypothesized to be related to genetic contributions23 and environmental factors,20,24 the developmental pathway of picky eating in early childhood is largely unknown.25 Moreover, the vast majority of research assessing picky eating behavior focuses on preschoolers (children aged 2–5 years), whereas much less attention has been paid to children aged ≤2 years. Unlike preschoolers, infants and toddlers are completely dependent on parents and caregivers to feed them and are learning how to eat through familiarization, observation, and associative learning.5 Previous reviews have addressed picky eating in terms of prevalence estimates, assessment methods, and relation to dietary intake, parent–child interactions, cognition, and social factors.26–28 Although these studies provide an extensive review of picky eating, the evidence on children aged ≤2 years of age and younger is still unclear. As best as could be determined, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the multilevel correlates of picky eating in this young child population has not previously been conducted.

The objective of this study was to systematically review existing scientific evidence of correlates of picky eating and food neophobia in children aged ≤2 years. The authors adopted a socioecological model as a theoretical framework to examine picky eating research.29 Correlates were classified into 4 broad categories—namely, cell (genetic and biological factors), child (individual characteristics of the child), clan (familial and parental factors), and community/country (factors outside of the home). Use of a socioecological framework to classify study findings into major categories allows for a better understanding of the context of picky eating behavior and highlights areas where additional research is warranted. Through the investigation of multidimensional factors of picky eating, this review also aids the development of evidence-based recommendations and interventions to promote healthy eating patterns and weight-gain trajectories in young children.

METHODS

Study selection criteria

Systematic review and meta-analysis procedures were conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information online).30,31 The PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes) framework (Table 1) was established a priori to formulate the systematic research question and to determine the inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies. Studies that met both of the following criteria were included in the review: (1) presented a quantitative analysis of at least 1 correlate of picky eating behavior or food neophobia in children aged ≤30 months and, (2) was published in English in a peer-reviewed publication. The age ceiling of 30 months rather than 24 months was imposed to retain studies that included a sample with children slightly older than 2 years. Some authors argue that children aged ≤12 months may be too young to exhibit a true reflection of picky eating.26 Because picky eating assessment is often based on parental perception26 and complementary feeding often begins in the first year of life,5 studies on children aged ≤12 months were included in this review. There were no restrictions on publication dates or type of study design. Longitudinal studies were included if the data presented in the article were consistent with the age limits (eg, if the study examined participants at aged 2 years and again at age 7 years, only baseline measurements at age 2 years were used). Articles were excluded from the review if they met any of the following criteria: not published in English; not peer reviewed (eg, dissertation or conference proceeding); review paper or case study; reported a study done exclusively on animals or adult subjects; or reported a study that evaluated only children with chronic diseases, developmental disability, autism spectrum disorder, or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Although review papers were not eligible for inclusion, relevant review articles were obtained and their reference lists were searched for eligible articles and to compare findings. If multiple publications were available from the same data source or study population, only the study with the most complete or recent data was included to prevent duplication. If the studies contained different information, then both were included.

Criteria used to define the research question for the systematic review

| Criteria . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Population | Children aged ≤30 mo without chronic diseases, developmental disability, autism spectrum disorder, or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder |

| Intervention | Any cross-sectional or experimental study examining a correlate of picky eating or food neophobia |

| Comparison | Not applicable |

| Outcome(s) | Picky eating, pickiness, fussy eating, choosy eating, faddy eating, food neophobia, food fussiness, or selective eating |

| Criteria . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Population | Children aged ≤30 mo without chronic diseases, developmental disability, autism spectrum disorder, or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder |

| Intervention | Any cross-sectional or experimental study examining a correlate of picky eating or food neophobia |

| Comparison | Not applicable |

| Outcome(s) | Picky eating, pickiness, fussy eating, choosy eating, faddy eating, food neophobia, food fussiness, or selective eating |

Criteria used to define the research question for the systematic review

| Criteria . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Population | Children aged ≤30 mo without chronic diseases, developmental disability, autism spectrum disorder, or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder |

| Intervention | Any cross-sectional or experimental study examining a correlate of picky eating or food neophobia |

| Comparison | Not applicable |

| Outcome(s) | Picky eating, pickiness, fussy eating, choosy eating, faddy eating, food neophobia, food fussiness, or selective eating |

| Criteria . | Description . |

|---|---|

| Population | Children aged ≤30 mo without chronic diseases, developmental disability, autism spectrum disorder, or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder |

| Intervention | Any cross-sectional or experimental study examining a correlate of picky eating or food neophobia |

| Comparison | Not applicable |

| Outcome(s) | Picky eating, pickiness, fussy eating, choosy eating, faddy eating, food neophobia, food fussiness, or selective eating |

Search strategy

Keyword searches were performed in 4 electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed, PyscINFO, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The search algorithm included all possible combinations of keywords from the following 2 groups: (1) “child,” “toddler,” “infant,” “baby,” or “babies” and (2) “picky eating,” “pickiness,” “fussy eating,” “choosy eating,” “faddy eating,” “food neophobia,” “food fussiness,” or “selective eating.” Titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the keyword search were screened against the study selection criteria by a single author (N.C.). Disagreement about study eligibility was solved through discussion with the coauthors (R.A., S.L., and S.D.). Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for evaluation of the full text by a single author (N.C.).

A reference list search (ie, backward reference search) and cited reference search (ie, forward reference search) were conducted based on the full-text articles meeting the study selection criteria that were identified from the keyword search. Articles identified from the backward and forward reference searches were further screened and evaluated using the same study selection criteria. Reference searches were repeated on all newly identified articles until no additional relevant article was found. The last search was completed on July 13, 2016.

Data extraction

A standardized data extraction form was used to collect the following methodological and outcome variables from each included study: author(s), publication year, country of study, study design, sample size, age of subjects, measurement tool(s) for assessing picky eating, method of reporting picky eating (ie, maternal report, parent report, etc.), prevalence of picky eating or food neophobia, specific picky eating behavior(s) of interest, and result(s) on the relationship of correlate(s) to picky eating. Data from included studies were extracted by one author (N.C.) and verified by a second author (R.A.). If there were missing data, then the corresponding author was contacted. Analysis included a narrative review of the correlates classified into 4 levels: cell, child, clan, and community/country. Food neophobia is often considered a subset of picky eating, and corresponding behaviors are frequently measured as 2 separate constructs because there is no clear distinction between them.28,32 Given that studies examining both picky eating and food neophobia were included in this review, the term picky eating is used when discussing overall findings, but food neophobia is specified when it was specifically measured.

Quantitative data synthesis

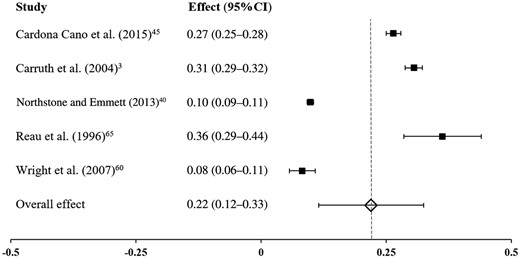

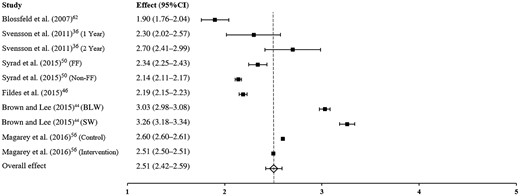

Meta-analysis was conducted to estimate (1) the prevalence of picky eating based on 5 studies that adopted a dichotomous definition for picky eating (ie, picky or not) and (2) the degree of picky eating based on 6 studies that adopted a continuous measure of picky eating—namely, the food fussiness subscale in the Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ). Due to data availability and measurement heterogeneity, additional meta-analyses could not be conducted on other covariates of picky eating such as sex, weight, and diet. Study heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 index. A random-effect model was estimated given an I2 statistic at or above 50%; otherwise, a fixed-effect model was estimated. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot and Begg’s and Egger’s tests. Meta-regression was performed to assess the relationship between the mean age of the study sample and the CEBQ food fussiness score. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 14.1 SE version (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical significance was set to P < 0.05.

Study quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using the following 6 criteria based on quality assessment scales from the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;33 the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute;34 and methods previously used35: (1) a priori aim/hypothesis specific to picky eating behaviors; (2) study population clearly specified and defined; (3) study design; (4) sample size; (5) reliable and valid measure of picky eating behavior; and (6) well-validated measure of correlate(s). Scores for each criterion range 0–2 depending on whether the criterion was unmentioned or unmet (0), partially met (1), or completely met (2). For the a priori aim/hypothesis criteria, studies that explicitly stated picky eating behaviors were given a score of 2, studies that implied picky eating (eg, eating difficulties) were given a score of 1, and studies that did not indicate an aim/hypothesis specific to picky eating were given a score of 0. For study design, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were given a score of 2, cohort studies were given a score of 1, and cross-sectional studies were given a score of 0. For sample size, study samples of ≥1000 were given a score of 2, samples of 100–999 were given a score of 1, and samples of <100 were given a score of 0. A total quality score ranging 0–12 was obtained for each study by summing the scores of each criterion. The overall study quality score helped measure the strength of the study evidence but was not used to determine the inclusion of studies in the review.

RESULTS

Study selection

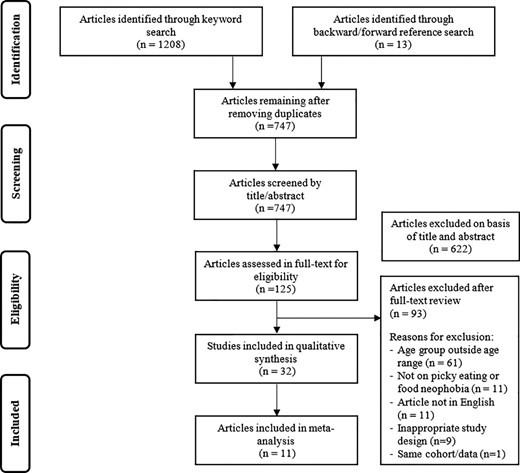

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study selection process and the reasons for exclusion. A total of 747 unduplicated articles were identified through keyword and reference searches, from which 622 were excluded in the title/abstract screening. The remaining 125 articles were reviewed in full text against the study selection criteria. Of these, 32 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Basic characteristics of the included studies

Table 2 summarizes the basic characteristics of the 32 articles included in the review. More than half of the studies (n = 22) were published from 2010 onward.36–57 Regarding study location, 20 were conducted in Europe (United Kingdom40,44,46,47,53–55,58–60; France39,49,50,57; Ireland48,61,62; Netherlands41,45; Sweden36); 5 studies were conducted in Australia38,42,43,51,56; 4 were conducted in the United States3,63–65; 1 was conducted in China37; 1 was conducted in Singapore52; and 1 was conducted in Canada.66 In terms of study design, 20 studies were cross-sectional3,37–40,43,46–49,51,54,55,58,60–65; 11 were longitudinal studies36,41,42,44,45,50,52,53,57,59,66; and 1 was an RCT.56 The sample sizes ranged from a small-scale preliminary study (n = 18)58 to a large longitudinal cohort (n = 9599).40 Five studies had a sample size of <100 participants36,41,58,61,62; 15 studies had a sample size of 100–99937–39,42–44,47,49,51,52,54,56,60,65,66; and 12 studies had a sample size >1000.3,40,45,46,48,50,53,55,57,59,63,64 The majority of studies (n = 24) included children during the transitional 12–24-month feeding period. However, some studies also included children aged <12 months3,63,64,66 or >24 months.43,47,54,60,65 In addition, 3 studies compared children who had been delivered preterm with those born full-term.39,55,66

Basic characteristics of the studies examining correlates of picky eating and food neophobia among young children

| Reference . | Country . | Study design . | Sample size . | Age, mo . | Measure of PE or FN . | Method of reporting PE or FN . | Prevalence of PE or FN . | Specific behavior of interest . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barends et al. (2014)41 | Netherlands | Longitudinal | 81 | 12–23 | Single questions | Maternal | NR | Picky eating, low food neophobiaa |

| Blossfeld et al. (2007)61 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 53 | 18 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Blossfeld et al. (2007)62 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 70 | 12 | Picky eating questionnaire; Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Picky eating, low food neophobiaa; food fussiness |

| Briefel et al. (2006)63 | United States | Cross-sectional | 3022 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | NR | Picky eating |

| Brown and Lee (2015)44 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 298 | 18–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Cao et al. (2012)37 | China | Cross-sectional | 219 | 12–18 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent or grandparent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | Netherlands | Longitudinal | 3618 | 18 | Child Behavior Checklist (2 items) | Maternal | 26.5% | Picky eating |

| Carruth et al. (2004)3 | United States | Cross-sectional | 3022 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | 30.5% | Picky eating |

| Cassells et al. (2014)42 | Australia | Longitudinal | 244 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Fildes et al. (2015)46 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 1044 | 16 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Fletcher et al. (2016)54 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 456 | 30 | Single question | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | United States | Cross-sectional | 2515 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | 42.2%b | Picky eating |

| Howard et al. (2012)38 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 245 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Jansen et al. (2014)43 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 462 | 21–27 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Johnson and Harris (2004)58 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 18 | 15–21 | CCTI Reaction to Food scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Johnson et al. (2016)55 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 1387 | 24c | Eating behavior questionnaire | Parent | NR | Picky eating/refusal |

| Magarey et al. (2016)56 | Australia | RCT (midline data) | 698 | 24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Maslin et al. (2015)47 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 126 | 8–30 | Picky eating questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Fussy eating |

| McCarthy et al. (2015)48 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 1189 | 24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Migraine et al. (2013)39 | France | Cross-sectional | 479 | 24c | Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Low food variety (picky eating + food neophobia) |

| Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 | France | Cross-sectional | 123 | 20–22 | Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Northstone and Emmett (2013)40 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 9599 | 24 | Single question | Maternal | 9.8% | Choosy (picky) eating |

| Northstone et al. (2001)59 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 9360 | 15 | Single question | Maternal | NR | Choosy (picky) eating |

| Oliveira et al. (2015)50 | France | Longitudinal | 1077 | 24 | Study-specific questions | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Perry et al. (2015)51 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 330 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Quah et al. (2015)52 | Singapore | Longitudinal | 210 | 12–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness/enjoyment of food |

| Reau et al. (1996)65 | United States | Cross-sectional | 151 | 13–27 | Single question | Parent | 36% | Picky eating |

| Sauve et al. (1991)66 | Canada | Longitudinal | 232 | 4–24c | Parent interviewd | Parent | 7.3%e | Fussy eating |

| Svensson et al. (2011)36 | Sweden | Longitudinal | 55 | 12–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Syrad et al. (2015)53 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 1897 | 16 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Wright et al. (2007)60 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 455 | 30 | Single question | Parent | 8.2% | Faddy (picky) eating |

| Yuan et al. (2016)57 | France | Longitudinal | 1142 | 12–24 | Study-specific questions | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Reference . | Country . | Study design . | Sample size . | Age, mo . | Measure of PE or FN . | Method of reporting PE or FN . | Prevalence of PE or FN . | Specific behavior of interest . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barends et al. (2014)41 | Netherlands | Longitudinal | 81 | 12–23 | Single questions | Maternal | NR | Picky eating, low food neophobiaa |

| Blossfeld et al. (2007)61 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 53 | 18 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Blossfeld et al. (2007)62 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 70 | 12 | Picky eating questionnaire; Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Picky eating, low food neophobiaa; food fussiness |

| Briefel et al. (2006)63 | United States | Cross-sectional | 3022 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | NR | Picky eating |

| Brown and Lee (2015)44 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 298 | 18–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Cao et al. (2012)37 | China | Cross-sectional | 219 | 12–18 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent or grandparent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | Netherlands | Longitudinal | 3618 | 18 | Child Behavior Checklist (2 items) | Maternal | 26.5% | Picky eating |

| Carruth et al. (2004)3 | United States | Cross-sectional | 3022 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | 30.5% | Picky eating |

| Cassells et al. (2014)42 | Australia | Longitudinal | 244 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Fildes et al. (2015)46 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 1044 | 16 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Fletcher et al. (2016)54 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 456 | 30 | Single question | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | United States | Cross-sectional | 2515 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | 42.2%b | Picky eating |

| Howard et al. (2012)38 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 245 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Jansen et al. (2014)43 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 462 | 21–27 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Johnson and Harris (2004)58 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 18 | 15–21 | CCTI Reaction to Food scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Johnson et al. (2016)55 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 1387 | 24c | Eating behavior questionnaire | Parent | NR | Picky eating/refusal |

| Magarey et al. (2016)56 | Australia | RCT (midline data) | 698 | 24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Maslin et al. (2015)47 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 126 | 8–30 | Picky eating questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Fussy eating |

| McCarthy et al. (2015)48 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 1189 | 24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Migraine et al. (2013)39 | France | Cross-sectional | 479 | 24c | Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Low food variety (picky eating + food neophobia) |

| Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 | France | Cross-sectional | 123 | 20–22 | Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Northstone and Emmett (2013)40 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 9599 | 24 | Single question | Maternal | 9.8% | Choosy (picky) eating |

| Northstone et al. (2001)59 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 9360 | 15 | Single question | Maternal | NR | Choosy (picky) eating |

| Oliveira et al. (2015)50 | France | Longitudinal | 1077 | 24 | Study-specific questions | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Perry et al. (2015)51 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 330 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Quah et al. (2015)52 | Singapore | Longitudinal | 210 | 12–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness/enjoyment of food |

| Reau et al. (1996)65 | United States | Cross-sectional | 151 | 13–27 | Single question | Parent | 36% | Picky eating |

| Sauve et al. (1991)66 | Canada | Longitudinal | 232 | 4–24c | Parent interviewd | Parent | 7.3%e | Fussy eating |

| Svensson et al. (2011)36 | Sweden | Longitudinal | 55 | 12–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Syrad et al. (2015)53 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 1897 | 16 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Wright et al. (2007)60 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 455 | 30 | Single question | Parent | 8.2% | Faddy (picky) eating |

| Yuan et al. (2016)57 | France | Longitudinal | 1142 | 12–24 | Study-specific questions | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

Abbreviations: CCTI, Colorado Childhood Temperament Inventory; FN, food neophobia; NR, not reported; PE, picky eating; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

aStudy measured openness/willingness to new foods (low food neophobia).

bBased on data from the same cohort as Carruth et al. (2004)3 but using a smaller sample size. Thus, only Carruth et al. (2004)3 was included in the meta-analysis to avoid duplication.

cCorrected age (study included children who were born preterm).

dFeeding problem was considered as present only if it was a major concern to parents or if it led to therapy or investigation.

eNot based on frequency response or dichotomization, thus not included in meta-analysis.

Basic characteristics of the studies examining correlates of picky eating and food neophobia among young children

| Reference . | Country . | Study design . | Sample size . | Age, mo . | Measure of PE or FN . | Method of reporting PE or FN . | Prevalence of PE or FN . | Specific behavior of interest . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barends et al. (2014)41 | Netherlands | Longitudinal | 81 | 12–23 | Single questions | Maternal | NR | Picky eating, low food neophobiaa |

| Blossfeld et al. (2007)61 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 53 | 18 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Blossfeld et al. (2007)62 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 70 | 12 | Picky eating questionnaire; Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Picky eating, low food neophobiaa; food fussiness |

| Briefel et al. (2006)63 | United States | Cross-sectional | 3022 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | NR | Picky eating |

| Brown and Lee (2015)44 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 298 | 18–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Cao et al. (2012)37 | China | Cross-sectional | 219 | 12–18 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent or grandparent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | Netherlands | Longitudinal | 3618 | 18 | Child Behavior Checklist (2 items) | Maternal | 26.5% | Picky eating |

| Carruth et al. (2004)3 | United States | Cross-sectional | 3022 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | 30.5% | Picky eating |

| Cassells et al. (2014)42 | Australia | Longitudinal | 244 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Fildes et al. (2015)46 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 1044 | 16 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Fletcher et al. (2016)54 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 456 | 30 | Single question | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | United States | Cross-sectional | 2515 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | 42.2%b | Picky eating |

| Howard et al. (2012)38 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 245 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Jansen et al. (2014)43 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 462 | 21–27 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Johnson and Harris (2004)58 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 18 | 15–21 | CCTI Reaction to Food scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Johnson et al. (2016)55 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 1387 | 24c | Eating behavior questionnaire | Parent | NR | Picky eating/refusal |

| Magarey et al. (2016)56 | Australia | RCT (midline data) | 698 | 24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Maslin et al. (2015)47 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 126 | 8–30 | Picky eating questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Fussy eating |

| McCarthy et al. (2015)48 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 1189 | 24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Migraine et al. (2013)39 | France | Cross-sectional | 479 | 24c | Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Low food variety (picky eating + food neophobia) |

| Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 | France | Cross-sectional | 123 | 20–22 | Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Northstone and Emmett (2013)40 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 9599 | 24 | Single question | Maternal | 9.8% | Choosy (picky) eating |

| Northstone et al. (2001)59 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 9360 | 15 | Single question | Maternal | NR | Choosy (picky) eating |

| Oliveira et al. (2015)50 | France | Longitudinal | 1077 | 24 | Study-specific questions | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Perry et al. (2015)51 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 330 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Quah et al. (2015)52 | Singapore | Longitudinal | 210 | 12–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness/enjoyment of food |

| Reau et al. (1996)65 | United States | Cross-sectional | 151 | 13–27 | Single question | Parent | 36% | Picky eating |

| Sauve et al. (1991)66 | Canada | Longitudinal | 232 | 4–24c | Parent interviewd | Parent | 7.3%e | Fussy eating |

| Svensson et al. (2011)36 | Sweden | Longitudinal | 55 | 12–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Syrad et al. (2015)53 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 1897 | 16 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Wright et al. (2007)60 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 455 | 30 | Single question | Parent | 8.2% | Faddy (picky) eating |

| Yuan et al. (2016)57 | France | Longitudinal | 1142 | 12–24 | Study-specific questions | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Reference . | Country . | Study design . | Sample size . | Age, mo . | Measure of PE or FN . | Method of reporting PE or FN . | Prevalence of PE or FN . | Specific behavior of interest . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barends et al. (2014)41 | Netherlands | Longitudinal | 81 | 12–23 | Single questions | Maternal | NR | Picky eating, low food neophobiaa |

| Blossfeld et al. (2007)61 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 53 | 18 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Blossfeld et al. (2007)62 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 70 | 12 | Picky eating questionnaire; Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Picky eating, low food neophobiaa; food fussiness |

| Briefel et al. (2006)63 | United States | Cross-sectional | 3022 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | NR | Picky eating |

| Brown and Lee (2015)44 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 298 | 18–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Cao et al. (2012)37 | China | Cross-sectional | 219 | 12–18 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent or grandparent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | Netherlands | Longitudinal | 3618 | 18 | Child Behavior Checklist (2 items) | Maternal | 26.5% | Picky eating |

| Carruth et al. (2004)3 | United States | Cross-sectional | 3022 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | 30.5% | Picky eating |

| Cassells et al. (2014)42 | Australia | Longitudinal | 244 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Fildes et al. (2015)46 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 1044 | 16 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Fletcher et al. (2016)54 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 456 | 30 | Single question | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | United States | Cross-sectional | 2515 | 4–24 | Single question | Parent or primary caregiver | 42.2%b | Picky eating |

| Howard et al. (2012)38 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 245 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Jansen et al. (2014)43 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 462 | 21–27 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Johnson and Harris (2004)58 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 18 | 15–21 | CCTI Reaction to Food scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Johnson et al. (2016)55 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 1387 | 24c | Eating behavior questionnaire | Parent | NR | Picky eating/refusal |

| Magarey et al. (2016)56 | Australia | RCT (midline data) | 698 | 24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Maslin et al. (2015)47 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 126 | 8–30 | Picky eating questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Fussy eating |

| McCarthy et al. (2015)48 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 1189 | 24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness |

| Migraine et al. (2013)39 | France | Cross-sectional | 479 | 24c | Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Low food variety (picky eating + food neophobia) |

| Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 | France | Cross-sectional | 123 | 20–22 | Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Northstone and Emmett (2013)40 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 9599 | 24 | Single question | Maternal | 9.8% | Choosy (picky) eating |

| Northstone et al. (2001)59 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 9360 | 15 | Single question | Maternal | NR | Choosy (picky) eating |

| Oliveira et al. (2015)50 | France | Longitudinal | 1077 | 24 | Study-specific questions | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Perry et al. (2015)51 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 330 | 24 | Child Food Neophobia Scale | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

| Quah et al. (2015)52 | Singapore | Longitudinal | 210 | 12–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Maternal | NR | Food fussiness/enjoyment of food |

| Reau et al. (1996)65 | United States | Cross-sectional | 151 | 13–27 | Single question | Parent | 36% | Picky eating |

| Sauve et al. (1991)66 | Canada | Longitudinal | 232 | 4–24c | Parent interviewd | Parent | 7.3%e | Fussy eating |

| Svensson et al. (2011)36 | Sweden | Longitudinal | 55 | 12–24 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Syrad et al. (2015)53 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 1897 | 16 | Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire | Parent | NR | Food fussiness |

| Wright et al. (2007)60 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 455 | 30 | Single question | Parent | 8.2% | Faddy (picky) eating |

| Yuan et al. (2016)57 | France | Longitudinal | 1142 | 12–24 | Study-specific questions | Maternal | NR | Food neophobia |

Abbreviations: CCTI, Colorado Childhood Temperament Inventory; FN, food neophobia; NR, not reported; PE, picky eating; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

aStudy measured openness/willingness to new foods (low food neophobia).

bBased on data from the same cohort as Carruth et al. (2004)3 but using a smaller sample size. Thus, only Carruth et al. (2004)3 was included in the meta-analysis to avoid duplication.

cCorrected age (study included children who were born preterm).

dFeeding problem was considered as present only if it was a major concern to parents or if it led to therapy or investigation.

eNot based on frequency response or dichotomization, thus not included in meta-analysis.

Of the 32 studies included in the review, 21 examined picky eating (ie, food fussiness, choosy eating, faddy eating, and fussy eating)3,36,37,40,43–48,52,53,55,56,59–61,63–66; 8 examined food neophobia38,42,49–51,54,57,58; and 3 investigated both picky eating and food neophobia.39,41,62 A variety of methods were used to assess picky eating and food neophobia, yet all studies relied on caregiver report (primarily the mother). There were 9 studies that used a single question (eg, “Is your child a picky eater?”)3,40,41,54,59,60,63–65 and 2 studies that used study-specific questions.50,57 The majority of studies (n = 20) used existing questionnaires, including the Picky Eating Questionnaire47,62; Eating Behavior Questionnaire55; CEBQ36,37,43,44,46,48,52,53,56,61,62; Child Food Neophobia Scale (CFNS)38,42,51; Children’s Eating Difficulties Questionnaire39,49; Child Behavior Checklist45; and the Reaction to Food scale from the Colorado Childhood Temperament Inventory (CCTI).58 The most commonly used questionnaire was the CEBQ (n = 11), which contains a food fussiness subscale that assesses picky eating behavior in children. Of the studies that examined food neophobia, the most commonly used tool was the CFNS (n = 3), which assesses a child’s willingness to try new foods.

Although the majority of studies used continuous measures of picky eating, several studies shared similar response categories for the frequency of picky eating (ie, Likert scales that were typically anchored by “never,” “sometimes”, and “always”) and dichotomized picky eating by combining responses of “sometimes” and “always” to be picky eaters and “never” and “rarely” to be nonpicky eaters. Of the 24 studies that investigated picky eating, 6 reported prevalence estimates of picky eating with sample sizes based on frequency responses and dichotomization.3,40,45,60,64,65 As shown in Table 2, prevalence estimates ranged 7%–36% for children aged 4–30 months.

Correlates of picky eating behaviors

A total of 89 correlates classified into 4 levels (ie, cell, child, clan, and community/country) were assessed, with the majority (n = 21) of studies assessing 1–4 correlates,36,40,41,46,48–59,61–63,65,66 and the remaining 11 assessing ≥5 correlates.3,37–39,42–45,47,60,64Table 3 reports a summary of the associations between potential correlates of picky eating and food neophobia.

Correlates of picky eating and food neophobia in young children

| Correlate . | Association with PE or FNa . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive . | Negative . | None . | |

| Cell: genetic and biological contributions | |||

| In utero factors | |||

| Born preterm | Johnson et al. (2016)55 | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | |

| Gestational age | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Medical issues | |||

| Child has an allergy | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Child has a long-term medical problem | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Illness (diarrhea, constipation, vomiting) | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Oral-motor-skill function | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Child: characteristics of the child | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Carruth et al. (2004)3; Svensson et al. (2011)36 | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Maslin et al. (2015)47 | |

| Birth order | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Sex | Cao et al. (2012)37 (girls) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Johnson et al. (2016)55; Maslin et al. (2015)47; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN); Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | |

| Race/ethnicity | Carruth et al. (2004)3b | ||

| Anthropometrics | |||

| Birth weight | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Hendricks et al. (2006)64; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN); Oliveira et al. (2015)50 (FN) | ||

| Current weight | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Carruth et al. (2004)3; McCarthy et al. (2015)48 | Cao et al. (2012)37; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN); Quah et al. (2015)52; Sauve et al. (1991)66; Wright et al. (2007)60 | |

| Height | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Weight gain | Quah et al. (2015)52; Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Behavior and food preferences | |||

| Smell differential reactivity | Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | ||

| Taste differential reactivity | Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | ||

| Appetite | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Enjoyment of food | Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Food responsiveness | Cao et al. (2012)37; Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Emotional overeating | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Desire to drink | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Satiety responsiveness | Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Slowness in eating/feeding time | Cao et al. (2012)37; Fildes et al. (2015)46; Reau et al. (1996)65 | ||

| Emotional undereating | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Temperament (difficultness) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Sour taste acceptance | Blossfeld et al. (2007)61 | ||

| Number of foods liked | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Fruit liking | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Vegetable liking | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Discretionary foods liking | Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Dietary intake | |||

| Dietary intake patterns | Northstone and Emmett (2013)40 | ||

| Number of foods tried | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Energy/caloric intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Carruth et al. (2004)3 | Sauve et al. (1991)66 | |

| Micronutrient intake | Carruth et al. (2004)3 | ||

| Vitamin/mineral supplement use | Briefel et al. (2006)63 | ||

| Complex texture intake | Blossfeld et al. (2007)62 (PFN) | ||

| Refined grain intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Whole grain intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Rice/pasta intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Dairy intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Fruit intake | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | |

| Vegetable intake | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | ||

| Meat intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Fish intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Composite dishes intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Discretionary foods intake | Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 (sweets) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 (savory); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) |

| Clan: parent characteristics and family dynamics | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Maternal age | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | Hendricks et al. (2006)64; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Number of children in household aged <18 y | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Marital status | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Employment status/mother currently working | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Maternal education | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | |

| Household income | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Diet and health | |||

| % total fruits disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| % total vegetables disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| % total other foods disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Having an overweight or obese parent | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Maternal weight | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Maternal food allergy history | Maslin et al. (2015)47 | ||

| Early feeding characteristics | |||

| Ever breastfed | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Maslin et al. (2015)47; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | |

| Mode of feeding (breast fed, formula fed, both) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Formula intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Extended formula feeding | Syrad et al. (2015)53 | ||

| Cow’s milk exclusion (for allergy) | Maslin et al. (2015)47 | ||

| Age first given solids | Northstone et al. (2001)59 (>10 mo) | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Northstone et al. (2001)59 (<6 mo) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) |

| Baby-led weaning | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | ||

| Long breastfeeding, later main meal food introduction, and use of homemade foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Later introduction of dairy products and use of ready-prepared baby foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Use of ready-prepared adult foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Feeding beliefs and practices | |||

| Offers new food before deciding child dislikes it | Carruth et al. (2004)3 | ||

| Covert restriction | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Mealtime negativity | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Concern about infant undereating/underweight | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Positive practices/responsive feeding | |||

| Awareness of infant hunger/satiety cues | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Monitoring | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | ||

| Structured meal setting | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Structured meal timing | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Family meal setting | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Negative practices/ nonresponsive feeding | |||

| Distrust in child’s appetite | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Overt restriction | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Pressure to eat/persuasive feeding | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Jansen et al. (2014)43 | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | |

| Reward for eating | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Reward for behavior | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Community/country: access to food/social influences | |||

| Guidance on protective feeding practices | Magarey et al. (2016)56 | ||

| Region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Residence (urban, suburban, rural) | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Child is a WIC recipient | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Child is in childcare | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Correlate . | Association with PE or FNa . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive . | Negative . | None . | |

| Cell: genetic and biological contributions | |||

| In utero factors | |||

| Born preterm | Johnson et al. (2016)55 | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | |

| Gestational age | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Medical issues | |||

| Child has an allergy | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Child has a long-term medical problem | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Illness (diarrhea, constipation, vomiting) | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Oral-motor-skill function | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Child: characteristics of the child | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Carruth et al. (2004)3; Svensson et al. (2011)36 | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Maslin et al. (2015)47 | |

| Birth order | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Sex | Cao et al. (2012)37 (girls) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Johnson et al. (2016)55; Maslin et al. (2015)47; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN); Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | |

| Race/ethnicity | Carruth et al. (2004)3b | ||

| Anthropometrics | |||

| Birth weight | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Hendricks et al. (2006)64; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN); Oliveira et al. (2015)50 (FN) | ||

| Current weight | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Carruth et al. (2004)3; McCarthy et al. (2015)48 | Cao et al. (2012)37; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN); Quah et al. (2015)52; Sauve et al. (1991)66; Wright et al. (2007)60 | |

| Height | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Weight gain | Quah et al. (2015)52; Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Behavior and food preferences | |||

| Smell differential reactivity | Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | ||

| Taste differential reactivity | Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | ||

| Appetite | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Enjoyment of food | Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Food responsiveness | Cao et al. (2012)37; Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Emotional overeating | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Desire to drink | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Satiety responsiveness | Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Slowness in eating/feeding time | Cao et al. (2012)37; Fildes et al. (2015)46; Reau et al. (1996)65 | ||

| Emotional undereating | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Temperament (difficultness) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Sour taste acceptance | Blossfeld et al. (2007)61 | ||

| Number of foods liked | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Fruit liking | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Vegetable liking | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Discretionary foods liking | Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Dietary intake | |||

| Dietary intake patterns | Northstone and Emmett (2013)40 | ||

| Number of foods tried | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Energy/caloric intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Carruth et al. (2004)3 | Sauve et al. (1991)66 | |

| Micronutrient intake | Carruth et al. (2004)3 | ||

| Vitamin/mineral supplement use | Briefel et al. (2006)63 | ||

| Complex texture intake | Blossfeld et al. (2007)62 (PFN) | ||

| Refined grain intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Whole grain intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Rice/pasta intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Dairy intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Fruit intake | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | |

| Vegetable intake | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | ||

| Meat intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Fish intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Composite dishes intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Discretionary foods intake | Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 (sweets) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 (savory); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) |

| Clan: parent characteristics and family dynamics | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Maternal age | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | Hendricks et al. (2006)64; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Number of children in household aged <18 y | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Marital status | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Employment status/mother currently working | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Maternal education | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | |

| Household income | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Diet and health | |||

| % total fruits disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| % total vegetables disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| % total other foods disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Having an overweight or obese parent | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Maternal weight | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Maternal food allergy history | Maslin et al. (2015)47 | ||

| Early feeding characteristics | |||

| Ever breastfed | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Maslin et al. (2015)47; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | |

| Mode of feeding (breast fed, formula fed, both) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Formula intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Extended formula feeding | Syrad et al. (2015)53 | ||

| Cow’s milk exclusion (for allergy) | Maslin et al. (2015)47 | ||

| Age first given solids | Northstone et al. (2001)59 (>10 mo) | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Northstone et al. (2001)59 (<6 mo) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) |

| Baby-led weaning | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | ||

| Long breastfeeding, later main meal food introduction, and use of homemade foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Later introduction of dairy products and use of ready-prepared baby foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Use of ready-prepared adult foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Feeding beliefs and practices | |||

| Offers new food before deciding child dislikes it | Carruth et al. (2004)3 | ||

| Covert restriction | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Mealtime negativity | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Concern about infant undereating/underweight | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Positive practices/responsive feeding | |||

| Awareness of infant hunger/satiety cues | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Monitoring | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | ||

| Structured meal setting | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Structured meal timing | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Family meal setting | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Negative practices/ nonresponsive feeding | |||

| Distrust in child’s appetite | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Overt restriction | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Pressure to eat/persuasive feeding | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Jansen et al. (2014)43 | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | |

| Reward for eating | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Reward for behavior | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Community/country: access to food/social influences | |||

| Guidance on protective feeding practices | Magarey et al. (2016)56 | ||

| Region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Residence (urban, suburban, rural) | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Child is a WIC recipient | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Child is in childcare | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

Abbreviations: FN, food neophobia; PE, picky eating; PFN, both picky eating and food neophobia; WIC, Women, Infants and Children (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program).

aAssociations are for picky eating unless otherwise specified.

Correlates of picky eating and food neophobia in young children

| Correlate . | Association with PE or FNa . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive . | Negative . | None . | |

| Cell: genetic and biological contributions | |||

| In utero factors | |||

| Born preterm | Johnson et al. (2016)55 | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | |

| Gestational age | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Medical issues | |||

| Child has an allergy | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Child has a long-term medical problem | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Illness (diarrhea, constipation, vomiting) | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Oral-motor-skill function | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Child: characteristics of the child | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Carruth et al. (2004)3; Svensson et al. (2011)36 | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Maslin et al. (2015)47 | |

| Birth order | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Sex | Cao et al. (2012)37 (girls) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Johnson et al. (2016)55; Maslin et al. (2015)47; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN); Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | |

| Race/ethnicity | Carruth et al. (2004)3b | ||

| Anthropometrics | |||

| Birth weight | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Hendricks et al. (2006)64; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN); Oliveira et al. (2015)50 (FN) | ||

| Current weight | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Carruth et al. (2004)3; McCarthy et al. (2015)48 | Cao et al. (2012)37; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN); Quah et al. (2015)52; Sauve et al. (1991)66; Wright et al. (2007)60 | |

| Height | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Weight gain | Quah et al. (2015)52; Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Behavior and food preferences | |||

| Smell differential reactivity | Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | ||

| Taste differential reactivity | Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | ||

| Appetite | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Enjoyment of food | Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Food responsiveness | Cao et al. (2012)37; Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Emotional overeating | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Desire to drink | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Satiety responsiveness | Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Slowness in eating/feeding time | Cao et al. (2012)37; Fildes et al. (2015)46; Reau et al. (1996)65 | ||

| Emotional undereating | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Temperament (difficultness) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Sour taste acceptance | Blossfeld et al. (2007)61 | ||

| Number of foods liked | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Fruit liking | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Vegetable liking | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Discretionary foods liking | Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Dietary intake | |||

| Dietary intake patterns | Northstone and Emmett (2013)40 | ||

| Number of foods tried | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Energy/caloric intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Carruth et al. (2004)3 | Sauve et al. (1991)66 | |

| Micronutrient intake | Carruth et al. (2004)3 | ||

| Vitamin/mineral supplement use | Briefel et al. (2006)63 | ||

| Complex texture intake | Blossfeld et al. (2007)62 (PFN) | ||

| Refined grain intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Whole grain intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Rice/pasta intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Dairy intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Fruit intake | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | |

| Vegetable intake | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | ||

| Meat intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Fish intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Composite dishes intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Discretionary foods intake | Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 (sweets) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 (savory); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) |

| Clan: parent characteristics and family dynamics | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Maternal age | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | Hendricks et al. (2006)64; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Number of children in household aged <18 y | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Marital status | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Employment status/mother currently working | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Maternal education | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | |

| Household income | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Diet and health | |||

| % total fruits disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| % total vegetables disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| % total other foods disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Having an overweight or obese parent | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Maternal weight | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Maternal food allergy history | Maslin et al. (2015)47 | ||

| Early feeding characteristics | |||

| Ever breastfed | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Maslin et al. (2015)47; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | |

| Mode of feeding (breast fed, formula fed, both) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Formula intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Extended formula feeding | Syrad et al. (2015)53 | ||

| Cow’s milk exclusion (for allergy) | Maslin et al. (2015)47 | ||

| Age first given solids | Northstone et al. (2001)59 (>10 mo) | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Northstone et al. (2001)59 (<6 mo) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) |

| Baby-led weaning | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | ||

| Long breastfeeding, later main meal food introduction, and use of homemade foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Later introduction of dairy products and use of ready-prepared baby foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Use of ready-prepared adult foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Feeding beliefs and practices | |||

| Offers new food before deciding child dislikes it | Carruth et al. (2004)3 | ||

| Covert restriction | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Mealtime negativity | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Concern about infant undereating/underweight | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Positive practices/responsive feeding | |||

| Awareness of infant hunger/satiety cues | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Monitoring | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | ||

| Structured meal setting | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Structured meal timing | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Family meal setting | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Negative practices/ nonresponsive feeding | |||

| Distrust in child’s appetite | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Overt restriction | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Pressure to eat/persuasive feeding | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Jansen et al. (2014)43 | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | |

| Reward for eating | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Reward for behavior | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Community/country: access to food/social influences | |||

| Guidance on protective feeding practices | Magarey et al. (2016)56 | ||

| Region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Residence (urban, suburban, rural) | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Child is a WIC recipient | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Child is in childcare | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Correlate . | Association with PE or FNa . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive . | Negative . | None . | |

| Cell: genetic and biological contributions | |||

| In utero factors | |||

| Born preterm | Johnson et al. (2016)55 | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | |

| Gestational age | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Medical issues | |||

| Child has an allergy | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Child has a long-term medical problem | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Illness (diarrhea, constipation, vomiting) | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Oral-motor-skill function | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Child: characteristics of the child | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Carruth et al. (2004)3; Svensson et al. (2011)36 | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Maslin et al. (2015)47 | |

| Birth order | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Sex | Cao et al. (2012)37 (girls) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Johnson et al. (2016)55; Maslin et al. (2015)47; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN); Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | |

| Race/ethnicity | Carruth et al. (2004)3b | ||

| Anthropometrics | |||

| Birth weight | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Hendricks et al. (2006)64; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN); Oliveira et al. (2015)50 (FN) | ||

| Current weight | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Carruth et al. (2004)3; McCarthy et al. (2015)48 | Cao et al. (2012)37; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN); Quah et al. (2015)52; Sauve et al. (1991)66; Wright et al. (2007)60 | |

| Height | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Weight gain | Quah et al. (2015)52; Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Behavior and food preferences | |||

| Smell differential reactivity | Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | ||

| Taste differential reactivity | Monnery-Patris et al. (2015)49 (FN) | ||

| Appetite | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Enjoyment of food | Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Food responsiveness | Cao et al. (2012)37; Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Emotional overeating | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Desire to drink | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Satiety responsiveness | Fildes et al. (2015)46 | ||

| Slowness in eating/feeding time | Cao et al. (2012)37; Fildes et al. (2015)46; Reau et al. (1996)65 | ||

| Emotional undereating | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Temperament (difficultness) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Sour taste acceptance | Blossfeld et al. (2007)61 | ||

| Number of foods liked | Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Fruit liking | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Vegetable liking | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Discretionary foods liking | Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | ||

| Dietary intake | |||

| Dietary intake patterns | Northstone and Emmett (2013)40 | ||

| Number of foods tried | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Wright et al. (2007)60 | ||

| Energy/caloric intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Carruth et al. (2004)3 | Sauve et al. (1991)66 | |

| Micronutrient intake | Carruth et al. (2004)3 | ||

| Vitamin/mineral supplement use | Briefel et al. (2006)63 | ||

| Complex texture intake | Blossfeld et al. (2007)62 (PFN) | ||

| Refined grain intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Whole grain intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Rice/pasta intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Dairy intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Fruit intake | Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) | |

| Vegetable intake | Barends et al. (2014)41 (PFN); Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45; Fletcher et al. (2016)54 (FN); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN); Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | ||

| Meat intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Fish intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Composite dishes intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Discretionary foods intake | Perry et al. (2015)51 (FN) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 (sweets) | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 (savory); Howard et al. (2012)38 (FN) |

| Clan: parent characteristics and family dynamics | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Maternal age | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | Hendricks et al. (2006)64; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Number of children in household aged <18 y | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Marital status | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Employment status/mother currently working | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Maternal education | Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | |

| Household income | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Diet and health | |||

| % total fruits disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| % total vegetables disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| % total other foods disliked by mother | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Having an overweight or obese parent | Cao et al. (2012)37 | ||

| Maternal weight | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Maternal food allergy history | Maslin et al. (2015)47 | ||

| Early feeding characteristics | |||

| Ever breastfed | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b; Maslin et al. (2015)47; Migraine et al. (2013)39 (PFN) | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | |

| Mode of feeding (breast fed, formula fed, both) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Formula intake | Cardona Cano et al. (2015)45 | ||

| Extended formula feeding | Syrad et al. (2015)53 | ||

| Cow’s milk exclusion (for allergy) | Maslin et al. (2015)47 | ||

| Age first given solids | Northstone et al. (2001)59 (>10 mo) | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Northstone et al. (2001)59 (<6 mo) | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) |

| Baby-led weaning | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | ||

| Long breastfeeding, later main meal food introduction, and use of homemade foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Later introduction of dairy products and use of ready-prepared baby foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Use of ready-prepared adult foods | Yuan et al. (2016)57 (FN) | ||

| Feeding beliefs and practices | |||

| Offers new food before deciding child dislikes it | Carruth et al. (2004)3 | ||

| Covert restriction | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Mealtime negativity | Johnson and Harris (2004)58 (FN) | ||

| Concern about infant undereating/underweight | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Positive practices/responsive feeding | |||

| Awareness of infant hunger/satiety cues | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN) | ||

| Monitoring | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | ||

| Structured meal setting | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Structured meal timing | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Family meal setting | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Negative practices/ nonresponsive feeding | |||

| Distrust in child’s appetite | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Overt restriction | Brown and Lee (2015)44; Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Pressure to eat/persuasive feeding | Cassells et al. (2014)42 (FN); Jansen et al. (2014)43 | Brown and Lee (2015)44 | |

| Reward for eating | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Reward for behavior | Jansen et al. (2014)43 | ||

| Community/country: access to food/social influences | |||

| Guidance on protective feeding practices | Magarey et al. (2016)56 | ||

| Region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Residence (urban, suburban, rural) | Carruth et al. (2004)3,b | ||

| Child is a WIC recipient | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

| Child is in childcare | Hendricks et al. (2006)64 | ||

Abbreviations: FN, food neophobia; PE, picky eating; PFN, both picky eating and food neophobia; WIC, Women, Infants and Children (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program).

aAssociations are for picky eating unless otherwise specified.

Cell: genetic and biological contributions

Four studies investigated genetic and biological correlates, such as in utero factors (being born preterm and gestational age) and medical issues.39,55,58,64 Evidence for picky eating and being born preterm was mixed in cross-sectional studies. One study found a positive association between being born preterm and picky eating,55 but another found no association.39 One cross-sectional study found no association between gestational age at birth and picky eating.39 Two cross-sectional studies examined the association between child medical issues and picky eating behaviors.58,64 Illness during late infancy (ie, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation) was positively associated with food neophobia.58 There was no association between picky eating and the child’s reported allergies,64 long-term medical problems,64 or oral-motor-skill function.58

Child: personal characteristics

Demographics.

Eleven studies investigated demographic correlates related to the child.3,36,37,39,41,42,45,47,49,55,64 The findings on picky eating in relation to age were mixed for both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies. Age was found to be positively associated with picky eating in 3 studies,3,36,41 but 2 studies found no association.42,47 Nine studies investigated the association between sex and picky eating; 2 were longitudinal studies,42,45 and 2 studies included children aged <12 months.3,47 Null findings were reported in general for the association between sex and picky eating; however, 1 cross-sectional study found a positive association among girls.37 There was no relationship between picky eating and birth order3 or child race/ethnicity.3

Anthropometrics.

Twelve studies examined the association between anthropometric measurements and picky eating behaviors.3,37,39,42,44,48,50–52,60,66 There was no association between birth weight and picky eating in cross-sectional39,64 or longitudinal studies.42,50 However, the evidence for current weight was mixed for both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies. Three studies found a negative association between current weight and picky eating,3,44,48 and 6 studies found no association.37,42,51,52,60,66 There was no association between picky eating and the child’s height60 or weight gain.52,60

Behavior and food preferences.

Nine studies investigated 16 correlates related to child behavior and food preferences.37,38,42,46,49,54,60,61,65 Picky eating was associated with lower appetite,60 enjoyment of food,46 food responsiveness,37,46 and desire to drink.37 One study found a positive association between differential reactivity to smell stimuli and food neophobia but no association between differential reactivity to taste stimuli and food neophobia.49 Picky eating was associated with higher satiety responsiveness,46 longer feeding time,37,46,65 and liking fewer foods,60 such as fruits and vegetables.38,54 There was no association between picky eating and emotional overeating or undereating,37 temperament (difficultness),42 sour taste acceptance,61 or liking of discretionary foods.38

Dietary intake.