-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dan Altman, By Fait Accompli, Not Coercion: How States Wrest Territory from Their Adversaries, International Studies Quarterly, Volume 61, Issue 4, December 2017, Pages 881–891, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx049

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In February 2014, Russia decided to wrest the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine. Moscow could have threatened to attack Ukraine if Kiev failed to relinquish Crimea. However, Russia did not attempt coercion. Russia unilaterally occupied and annexed the territory, gambling that it could take Crimea without provoking war. This alternative strategy—the fait accompli—receives little scholarly attention. At issue is a fundamental question of statecraft in international politics: How do states make gains? By coercion or by fait accompli? Territorial acquisitions offer the best single-issue domain within which to address this question. Using new data on all “land grabs” since 1918, this research note documents a stark discrepancy. From 1918 to 2016, 112 land grabs seized territory by fait accompli. In that same span, only thirteen publicly declared coercive threats elicited cessions of territory. This fact suggests that the fait accompli deserves a larger role in the field's thinking about strategy and statecraft on the brink of war. It carries with it important implications for canonical theories of war that rely on assumptions about coercive bargaining during crises.

In February 2014, Russia decided to wrest the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine. Moscow could have threatened to attack Ukraine if Kiev failed to relinquish Crimea. Moscow could even have consulted an impressive body of international relations research on credible threats and coercion for guidance.1 However, Russia did not attempt coercion. Instead, Russia unilaterally occupied and annexed the territory, gambling that it could take Crimea without provoking war. This alternative strategy—the fait accompli—receives little scholarly attention. In the literature's understanding of statecraft on the brink of war, the fait accompli has lived in the shadow of coercion. This longstanding prioritization of coercion emerges from a plausible assumption that scholars typically leave implicit: states ordinarily make gains by coercion, while the fait accompli is a comparative rarity. If so, Crimea was little more than an exception to normal international conduct.

This note upends that assumption. It establishes that states far more often acquire territory by fait accompli than by coercion. At issue is a fundamental question of statecraft in international politics: How do states make gains? Short of prevailing in a war, how does a state acquire something from an adversary that does not wish to surrender it? Territorial gains offer a domain within which to address this question. Using new data on all “land grabs” since 1918, this research note documents a stark discrepancy. From 1918 to 2016, 112 land grabs seized territory by fait accompli, with Crimea being the most recent. In that same span, only thirteen publicly declared coercive threats elicited cessions of territory. This fact has direct implications for strategy, statecraft, and scenario planning. It raises questions about canonical theories of war that rely on assumptions about coercive bargaining during crises (see Fearon 1995).

Although faits accomplis take many forms, territorial acquisitions offer the best single-issue domain within which to examine how frequently each strategy makes gains, for two reasons. First, territory has long ranked as perhaps the foremost issue over which states come into conflict—and the issue most associated with the onset of war (Vasquez and Henehan 2001). Second, the outcomes of conflicts—the extent to which each side “won” or “lost”—often prove difficult to measure (see, for instance, Jones, Stuart, and Bremer 1996, 179). Change in the military control of territory offers a comparatively clear basis for identifying gains and losses.

The possibility that states most often acquire territory by coercion is no straw man. Quite the opposite, the rarity of territorial gains through coercion should come as a surprise. Consider the influential case of the Munich Crisis in 1938. German threats coerced Czechoslovakia into relinquishing the Sudetenland. Munich offers a plausible general model for statecraft, but not a representative model. Since 1918, land grabs such as Russia's seizure of Crimea remained the norm; coerced cessions like the Sudetenland proved the exception. Moreover, most of the coercion successes occurred immediately prior to the Second World War. From 1945 onward, coercive threats have only resulted in territorial acquisition twice, as compared to eighty-two land grabs in this period.

This research note proceeds as follows. The first section explains the fait accompli as a concept, making the case that it deserves a seat at the table in the field's understanding of strategy and statecraft. With the notable exception of a recent study by Tarar (2016), which I consider below, the fait accompli has received remarkably little scholarly attention until now. The second section explores the significance of the fait accompli for widely held theories of the causes of war. The third details the creation of new data on land grabs from 1918 to 2016. Existing studies of territorial conflict often remark upon the importance of land grabs, but until now the data to evaluate this phenomenon directly have not existed.2 The fourth establishes that states far more often made territorial gains by fait accompli than by coercion in the 1918–2016 period. The study concludes with a discussion of the questions raised by this finding and points to the need for a new body of research on faits accomplis.

The Fait Accompli

Suppose a criminal armed with a handgun encounters a wealthy man holding his wallet. The criminal can acquire that wallet in three basic ways. First, the criminal can shoot the victim, then take it. The strategy: brute force. Second, the criminal can brandish the gun, threaten to shoot, and intimidate the man into surrendering his wallet. The strategy: coercion. Or, third, the criminal can reach out and grab the wallet, calculating that the victim will not attack an armed man to regain it. The strategy: fait accompli. States seeking to make gains select from the same three fundamental options, yet the international relations literature has focused overwhelmingly on just two.

In his foundational study of strategy and statecraft, Schelling (1966, 1–34) established the distinction between brute force and coercion. Through all-out invasion, regime change, or mass killings, challengers can impose a desired outcome without the consent of the defender. Alternatively, challengers can threaten to inflict harm if their demands go unfulfilled, making gains by coercion when the defender meets those demands. Schelling's distinction, although crucially important, omits and perhaps obscures the fait accompli as a third fundamental way to make gains.3 This stems from his focus on only the most aggressive forms of brute force. Although the fait accompli is, like brute force, a unilateral imposition, it takes place on a far smaller and sometimes nonviolent scale. The challenger aims to escape escalation rather than prevail after it. Unlike brute force, a fait accompli does not violently disarm, disable, or destroy the defender.4

A fait accompli imposes a limited unilateral gain at an adversary's expense in an attempt to get away with that gain when the adversary chooses to relent rather than escalate in retaliation.5 Each fait accompli is a calculated risk. Whether it results in a successful gain or escalation depends on whether the challenger has successfully gauged the level of loss the defender will accept. Take too much and the defender will prefer war to tolerating the loss. Sometimes this strategy succeeds, as with Iran's 1971 occupation of Abu Musa and nearby islands in the Persian Gulf. Other faits accomplis fail when they provoke a stronger response than had been hoped. Argentina's 1982 attempt to get away with seizing the Falkland Islands backfired when it provoked a British counterattack.

The fait accompli is unsuitable for maximalist aims such as conquering an adversary outright or changing a regime. A fait accompli aims to take a gain small enough that the adversary will let it go rather than escalate.6 Military operations intended as the initial phase of a brute force campaign with unlimited aims are not faits accomplis. Although most faits accomplis—including many land grabs—are small in size, even small land grabs can have large implications. For instance, the two deadliest armed clashes between nuclear powers each began with a sudden deployment of troops to occupy a small region along a disputed border: the Sino-Soviet border conflict in 1969 (Damansky Island) and the Indo-Pakistani conflict in 1999 (Kargil).

Coercion and the fait accompli are two fundamentally different ways of acquiring something from an adversary. Faits accomplis make gains unilaterally, imposing a change to the status quo without the adversary's consent. Coercive threats, in contrast, pressure the adversary into consenting to a concession, however reluctantly.7 As the primary strategies for wresting gains from recalcitrant adversaries, short of taking them after winning a war, this study focuses on these two alternatives.

More precisely, the fait accompli is an alternative to the specific type of coercion available to challengers: compellence. Compellence is coercion demanding a revision to the status quo, unlike deterrence, which employs threats to preserve the status quo.8 In his studies of compellence, Sechser (2011; Sechser and Fuhrmann 2013) draws exactly this distinction between coercive gains and gains by fait accompli, referring to them as “compellence” and “compulsion,” respectively. Sechser addresses compulsion primarily for methodological reasons. The problem: in cases where the challenger attempted compellence, the defender rebuffed the threat, and the challenger then took what it wanted by force. Without the separate outcome category of compulsion, such cases wrongly register as successes for coercion.9 Although much of the literature uses the term coercion to encompass both deterrence and compellence, this study follows others who use the term more narrowly to mean compellence (for example, Pape 1996). Another appropriate term is ultimatum bargaining.

Surprise is an important characteristic of many—but not all—faits accomplis.10 With respect to land grabs, partial surprise is typical. Explicit ultimatums demanding territory and setting deadlines are rare, so some degree of surprise is normal. However, states rarely seize territory without first declaring a public claim to it, so total surprise is unusual.11

Faits accomplis have received surprisingly little attention in the international relations literature. Only one peer-reviewed article in international relations addresses the fait accompli as its primary subject. Tarar (2016) uses formal modeling to introduce the fait accompli into established bargaining theories of war. Tarar offers two explanations for the occurrence of faits accomplis. First, the informational explanation holds that defenders’ uncertainty about the feasibility (costliness) of a fait accompli leads to an unwillingness to offer sufficient concessions.12 Challengers then resort to a fait accompli. Second, the commitment-problems explanation posits a first-strike advantage. Challengers impose faits accomplis suddenly and by surprise in order to avoid having the defender make military preparations that would increase the costs of a future fait accompli.

Prior to Tarar's article, the most significant discussion of the fait accompli appeared amid studies of the causes of war. These scholars regard the fait accompli as a risky crisis tactic, one that exacerbates the likelihood of war (Snyder and Diesing 1977, 227; Van Evera 1998, 10). Van Evera, for instance, characterizes the fait accompli as a “halfway step to war.” In their study of deterrence, George and Smoke (1974, 536–40) identify faits accomplis as an intermediate form of deterrence failure. From that perspective, faits accomplis are worse for the deterrer than maintaining the status quo but better than an unlimited attack. Mearsheimer (1983, 53–58) encompasses faits accomplis within the military strategy of “limited aims.” Unlike the alternative strategies of blitzkrieg and attrition, a limited aims attack consists of a sudden operation to seize a border region while engaging only a small fraction of the enemy's forces. Mearsheimer regards this strategy with skepticism, arguing that even a limited aims attack will make a “lengthy war of attrition…very likely because the defender's key decision makers will undoubtedly be under great pressure to recapture lost territory.” However, most land grabs do not start wars. Fewer still provoke high-intensity wars of attrition. Military strategy does not offer the best lens for understanding land grabs. The fait accompli is first and foremost a political strategy, one that aspires not to require a military strategy.

Although providing an important starting point for thinking about faits accomplis, the literature lacks a clear sense of how prevalent they are in international politics. One might read this literature in full and come away with the impression that the fait accompli is a niche phenomenon seen in a handful of cases, not something of importance for general theories of international relations.

The Significance of the Fait Accompli for the Bargaining Model of War

If, as this note will show, states far more often make territorial gains by fait accompli than by coercion, what does it mean for existing theories of international relations? This section examines the implications for the foremost research question in the field: the causes of war. In particular, the surprising rarity of coerced territorial gains raises questions about the bargaining model of war (Fearon 1995). Assumptions about coercive bargaining in crises anchor this widely held rationalist theory of war. Consequently, understanding the true process of strategic interaction in crises is a first-order issue for international relations theory. I begin by refuting a prima facie plausible line of reasoning that regards the rarity of coerced territorial cessions as an outright falsification of the bargaining model. Nonetheless, I then explain why the predominance of gains by fait accompli may lead to important changes to theories built around the bargaining model.

At first glance, the greater prevalence of faits accomplis relative to coerced concessions seems to destabilize established bargaining theories of war. According to Reiter (2003, 31), “The bargaining model proposes that exercising brute force to accomplish limited aims is generally misguided.” Since Fearon's seminal article, the field has increasingly come to conceive of war as the result of a failure to reach a war-averting coercive bargain. Peace endures when threats of war lead one side to give up enough so that the other no longer prefers a costly war to a peaceful bargain (Fearon 1995; Wagner 2000). Therefore, the rarity of coerced bargains in the issue area most associated with the onset of war—territory—seems to pose a severe problem. How can coercive bargaining preserve the peace if there are so few coerced bargains? Indeed, territory commonly provides the explicit if stylized stakes for these models (for example, Fearon 1995; Filson and Werner 2002, 825; Powell 2004, 2006).

However, the rarity of coerced cessions does not in itself falsify the bargaining model. Each fait accompli can function as a tacit bargain. The required war-avoiding concession takes the form of a decision not to escalate in response to a fait accompli.13 Although not an invalidation of the framework, this changes the nature of the envisioned bargaining process. That process no longer requires negotiation, coercive threats, or verbal bargaining of any kind. This may falsify narrower interpretations of the bargaining model. Stripped of these elements, however, the underlying premise remains intact. The two sides avoid war when both find agreeing to the new status quo preferable to war.14

The implications extend further. The relative prevalence of gains by fait accompli raises serious questions about the role of signaling in crisis bargaining. Because the bargaining model literature regards uncertainty as perhaps the foremost cause of bargaining failure and war, it places a primary emphasis on crisis signaling. These signals of resolve include military deployments intended as shows of force and public statements of commitment that put audience costs on the line (Fearon 1997; Slantchev 2011; Trager and Vavreck 2011; but see Slantchev 2010; Snyder and Borghard 2011). This is not an abstract concern. Signaling is the concept most often applied to interpret state behavior during crises. According to Fearon (1994a), “States resort to the risky and provocative actions that characterize crises (i.e., mobilization and deployment of troops and public warnings or threats about the use of force) because less-public diplomacy may not allow them to credibly reveal their own preferences.”

However, signals of resolve do not seem to contribute to intimidating states into granting territorial concessions with any regularity. States practicing coercion must convey their resolve effectively to receive a concession. In contrast, states can take a gain by fait accompli without preparatory signaling.

The full connection between signaling and the prevalence of faits accomplis is perhaps surprising. It emerges only through a consideration of the likely reasons why territorial gains by fait accompli are so much more common than gains by coercion. To my knowledge, the following four are the only unitary rationalist explanations for the greater prevalence of land grabs relative to coerced territorial cessions.15 That is, these explanations accord with the simplifying assumption that states are singular actors that rationally pursue their interests (Fearon 1995). If validated, any or all of the four would undercut the significance of traditional crisis signals of resolve, each in its own way. I illustrate each with hypothetical (illustrative-only) explanations of Russia's fait accompli in Crimea.16

The first explanation is simply that states are unable to find signals costly enough (or otherwise credible enough) to convince adversaries of their resolve. If so, challengers can make gains by fait accompli, by brute force, or not at all. To illustrate using the case of Crimea, perhaps Russia doubted that issuing an ultimatum and mobilizing forces near Crimea would convince Ukraine that Russia would truly seize it by force. If signaling is this difficult, whether for rational or psychological reasons (Jervis, Lebow, and Stein 1989), its role in crises is likely overstated.

A second—and very different—explanation is the value of surprise. If the element of surprise provides an important tactical advantage for faits accomplis, challengers may forgo the signals and explicit threats necessary to coerce concessions (Tarar 2016). This would negate their role. Eschewing signals and threats prevents the defender from consolidating its position with reinforcements or fortifications (Carter 2010). For example, Russia's sudden and secretive invasion of Crimea using soldiers without identifying insignia gave Ukraine little time to prepare or deploy troops whose loyalty was not in question. Russia may have chosen to forgo coercion for that reason.

Third, the decision to attempt coercion rather than impose a fait accompli may screen out the most resolute challengers, crippling the credibility of subsequent coercive threats.17 If the threat is sincere, why did the challenger not simply take the territory at the outset? The absence of a fait accompli may function as an implicit signal of weakness that supersedes ensuing signals of resolve.18 In Crimea, suppose that Russia believed Ukraine would interpret the decision to demand Crimea rather than seize it as a sign of low resolve. If so, Russia had no reason to make a coercive threat that it expected would fail.

Finally, suppose that losing territory to a land grab is not significantly costlier than losing it to a coercive threat as a concession. If so, defenders may opt to make challengers prove that they are in fact willing to risk war to take the territory. By rejecting the challenger's threat, the defender preserves the possibility of retaining the territory if the challenger is bluffing. Defenders may prefer a slim chance of keeping the territory if the challenger is bluffing to the certainty of losing it by capitulating. In the Crimean context, this explanation posits that Ukraine would have preferred the possibility of retaining Crimea by rejecting Russian demands to the certainty of losing Crimea after agreeing to cede it. Anticipating this, Russia issued no threats and chose instead to impose a fait accompli.

In sum, it is surprisingly difficult to reconcile the rarity of territorial gains by coercion with the prevailing conceptualization of state behavior during crises: signals of resolve designed to endow coercive threats with credibility. This matters because assumptions about the nature of strategic interactions on the brink of war lay the foundations for larger theories of international politics. For instance, popular theories explaining both the democratic peace and the peace-promoting effect of bilateral trade rely on crucial assumptions about the importance of signals of resolve (Schultz 1998; Morrow 1999a; Gartzke, Li, and Boehmer 2001). A reduced role for signaling during crises may call into question bedrock theories of international relations. Replacing coercive threats with faits accomplis has implications that extend far beyond the subjects of crisis statecraft and territorial conflict.

Data and Measurement

In territorial conflicts, the fait accompli takes the form of the land grab. Coercion makes territorial gains in the form of cessions under threat. This section summarizes the definitions and measurement of each. It details the creation of new data on land grabs.

A land grab is a military deployment that seizes a disputed piece of territory with the intention to assume lasting control. Each state can commit a maximum of one land grab in one militarized dispute or crisis. I do not distinguish, for instance, between seizing one island and seizing a group of islands if these seizures occur within the same militarized dispute. This definition of land grab excludes most cross-border military operations because they lack an intention to assume control of additional territory (that is, to change the border).19 Incursions other than land grabs include interventions in civil wars, raids on rebel bases, peacekeeping missions, and navigational errors by military patrols.

Land grabs are a form of behavior, not an outcome. To qualify as a land grab, the challenger must occupy disputed territory that it did not previously hold. There is no minimum time for which the challenger must retain the territory. The eventual outcome—whether the challenger keeps lasting control of the territory—does not factor into the definition. Nonetheless, I discuss the longer-term fates of land grabs in the next section. Many land grabs seize territory occupied by the armed forces of another state. Others seize unoccupied territories claimed by both sides. In part for this reason, some land grabs use violence from the start. Others acquire territory without casualties.

All faits accomplis seizing territories are land grabs. However, a small number of land grabs likely were not faits accomplis. The definition of fait accompli requires an attempt to get away with a gain when the adversary chooses to relent rather than escalate in retaliation. Due to the difficulty of observing this intent, the definition of land grab does not include this requirement. In a few cases, it appears that the challenger embarked on the land grab expecting that war would ensue. The 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli Wars illustrate this point.20 They contrast with, for example, Argentina's ambition to get away with seizing the Falkland Islands.

To identify land grabs between 1918 and 2016, I made use of several event and territorial conflict datasets: the Interstate Crisis Behavior, Militarized Interstate Disputes, Correlates of War, and Territorial Change datasets, and a variety of other sources.21 I then used secondary sources to confirm the existence of a land grab and gather additional information about it. It proved infeasible to identify cases in which states occupied small territories without any public controversy or complaint. Consequently, land grabs occur within an accompanying dispute, crisis, or war.

Why new data? The Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) and Territorial Change datasets contain variables that seem similar, but neither can generate a similar list of land grabs.22 The MID dataset includes the “highest action” (in terms of escalation) taken by each actor during a dispute. Although the fourteenth level of this variable is “occupation of territory,” cases only enter this category when no higher escalation occurs. Any case that escalates to, for instance, “attack” (level 17), “clash” (level 18), or war (levels 20 and 21) does not qualify as an occupation of territory. This leaves out many land grabs.23 Moreover, most occupations of territory are not land grabs, but rather cross-border incursions for other purposes. Similarly, the Territorial Change dataset includes land grabs in three of its seven categories: “conquest,” “annexation,” and (more rarely) “cession.” Each category contains many events other than land grabs, including coerced cessions and legal settlements.24

To assess how often states gain territory by coercion, I utilize Sechser's (2011) definition: “an explicit demand by one state (the challenger) that another state (the target) alter the status quo in some material way, backed by a threat of military force if the target does not comply.” This definition includes verbal threats to take territory in a land grab. Sechser used this definition to create the Militarized Compellent Threats (MCT) dataset. This dataset is the principal source of the list of coerced cessions in the next section. Despite using the same definitions of coercion and success, I identify fewer instances of successful territorial coercion than Sechser. The discrepancy arises mainly because I define territorial issues more narrowly, requiring an attempt to modify land borders. Sechser treats a broader range of issues as territorial in nature, including the use of roads, control of canals, and fishing rights in disputed waters. Several instances of successful territorial coercion in the MCT dataset involve stakes smaller than control over land.

Finally, I exclude from the following analysis all cases like Iraq's 1990 invasion of Kuwait, where one state sought control over the full territory of another.25 Neither coercion nor the fait accompli suits this unlimited objective. By definition, faits accomplis seize something of limited value in an attempt to get away with the gain without provoking war. Attempting to conquer an entire state implies a brute force strategy and leaves the adversary with no choice but to fight a war or lose everything.26 Similarly, coercion relies on asking for little enough that the other side prefers capitulation to resistance. The next section presents data on these alternative strategies for making limited territorial gains.

How States Wrest Territory from Their Adversaries

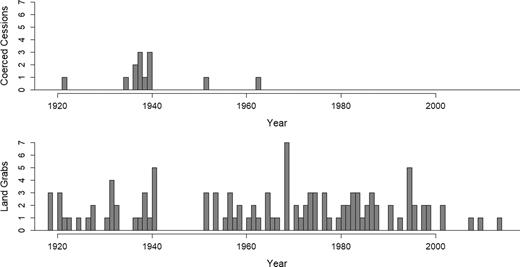

The data reveal that states far more often acquire territory by fait accompli than by coercion. When Argentina took the Falkland Islands from Britain in 1981, it did so in a surprise fait accompli. When Britain resolved to regain the islands, it demanded their return. Argentina refused. British forces then retook the islands in an invasion of their own while carefully avoiding attacks on Argentina itself, even on Argentinean naval vessels in port. When India confronted Portugal with demands for the enclave of Goa—demands backed by an overwhelming advantage in military power in the region—the Portuguese government refused. Portugal held its ground and ordered its forces to fight to the end. Giving up on threats, India occupied Goa by force in 1961 (Goncalves 2003). These examples fit the broader pattern. Figure 1 compares the history of territorial acquisitions by coercion to acquisitions by fait accompli from 1918 to 2016.

States make territorial gains by coercion with surprising rarity. Not once in the last fifty years has a publicly declared threat coerced a state into ceding territory without the coercer deploying its military to seize the territory first. Only two coerced territorial cessions took place after 1945.27 In the most recent case, Indonesia pressured the Netherlands into relinquishing West Irian (West Papua) in 1963. In 1952, Greece mobilized forces and bombarded Bulgarian troops who had just occupied Gamma Island, a small disputed island in the Evros River. The small Bulgarian force then complied with the Greek ultimatum to withdraw (Chicago Daily Tribune 1952). In the full period, 1918 to 2016, the number of coerced territorial cessions grows to thirteen.28 Table 1 lists these coerced cessions.

Coerced territorial cessions, 1918–2016

| Year . | Coercer . | Target . | Territory . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1922 | Turkey | Britain | Constantinople; Eastern Thrace |

| 1935 | Japan | China | Hebei; Chahar |

| 1937 | Turkey | France | Hatay (Alexandretta) |

| 1937 | Japan | Soviet Union | Amur River Islands |

| 1938 | Germany | Czechoslovakia | Sudetenland |

| 1938 | Hungary | Czechoslovakia | Southern Slovakia |

| 1938 | Poland | Czechoslovakia | Teschen |

| 1939 | Germany | Lithuania | Memel |

| 1940 | Soviet Union | Romania | Bessarabia; Northern Bukovina |

| 1940 | Bulgaria | Romania | Southern Dobruja |

| 1940 | Hungary | Romania | Northern Transylvania |

| 1952 | Greece | Bulgaria | Gamma Island |

| 1963 | Indonesia | Netherlands | West Irian (West Papua) |

| Year . | Coercer . | Target . | Territory . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1922 | Turkey | Britain | Constantinople; Eastern Thrace |

| 1935 | Japan | China | Hebei; Chahar |

| 1937 | Turkey | France | Hatay (Alexandretta) |

| 1937 | Japan | Soviet Union | Amur River Islands |

| 1938 | Germany | Czechoslovakia | Sudetenland |

| 1938 | Hungary | Czechoslovakia | Southern Slovakia |

| 1938 | Poland | Czechoslovakia | Teschen |

| 1939 | Germany | Lithuania | Memel |

| 1940 | Soviet Union | Romania | Bessarabia; Northern Bukovina |

| 1940 | Bulgaria | Romania | Southern Dobruja |

| 1940 | Hungary | Romania | Northern Transylvania |

| 1952 | Greece | Bulgaria | Gamma Island |

| 1963 | Indonesia | Netherlands | West Irian (West Papua) |

Coerced territorial cessions, 1918–2016

| Year . | Coercer . | Target . | Territory . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1922 | Turkey | Britain | Constantinople; Eastern Thrace |

| 1935 | Japan | China | Hebei; Chahar |

| 1937 | Turkey | France | Hatay (Alexandretta) |

| 1937 | Japan | Soviet Union | Amur River Islands |

| 1938 | Germany | Czechoslovakia | Sudetenland |

| 1938 | Hungary | Czechoslovakia | Southern Slovakia |

| 1938 | Poland | Czechoslovakia | Teschen |

| 1939 | Germany | Lithuania | Memel |

| 1940 | Soviet Union | Romania | Bessarabia; Northern Bukovina |

| 1940 | Bulgaria | Romania | Southern Dobruja |

| 1940 | Hungary | Romania | Northern Transylvania |

| 1952 | Greece | Bulgaria | Gamma Island |

| 1963 | Indonesia | Netherlands | West Irian (West Papua) |

| Year . | Coercer . | Target . | Territory . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1922 | Turkey | Britain | Constantinople; Eastern Thrace |

| 1935 | Japan | China | Hebei; Chahar |

| 1937 | Turkey | France | Hatay (Alexandretta) |

| 1937 | Japan | Soviet Union | Amur River Islands |

| 1938 | Germany | Czechoslovakia | Sudetenland |

| 1938 | Hungary | Czechoslovakia | Southern Slovakia |

| 1938 | Poland | Czechoslovakia | Teschen |

| 1939 | Germany | Lithuania | Memel |

| 1940 | Soviet Union | Romania | Bessarabia; Northern Bukovina |

| 1940 | Bulgaria | Romania | Southern Dobruja |

| 1940 | Hungary | Romania | Northern Transylvania |

| 1952 | Greece | Bulgaria | Gamma Island |

| 1963 | Indonesia | Netherlands | West Irian (West Papua) |

In contrast, states have unilaterally deployed military forces to seize territory 112 times since 1918. Eighty-two of these occurred since 1945, which offers a particularly stark contrast to the two coerced cessions during that period. Table 2 lists these land grabs. The table contains eighty-four distinct cases. The asterisks mark the twenty-eight that provoked an immediate retaliatory land grab.29 These cases each contain two land grabs. All but a few of the retaliatory land grabs retook the seized territory.

Land grabs, 1918–2016

| . | Land Grab . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year . | By . | Against . | Territory . | War . |

| 1919 | Romania | Russia | Bessarabia | |

| 1919 | Finland | Russia* | East Karelia (p) | |

| 1921 | Costa Rica | Panama* | Coto | |

| 1921 | Yugoslavia | Albania | Northern Albania | |

| 1922 | Turkey | Britain | Chanak | |

| 1923 | Italy | Greece | Corfu | |

| 1925 | Russia | Afghanistan | Urta-Tugai | |

| 1927 | Norway | Britain | Bouvet Island | |

| 1928 | Paraguay | Bolivia* | Chaco (p) | |

| 1931 | Japan | China | Manchuria | X |

| 1932 | Bolivia | Paraguay* | Chaco (p) | X |

| 1932 | Peru | Colombia* | Leticia | |

| 1933 | North Yemen | Saudi Arabia* | Najran (Asir) | X |

| 1937 | Russia | Japan | Amur River Islands | |

| 1938 | Russia | Japan | Changkufeng | X |

| 1939 | Japan | Russia* | Nomonhan | X |

| 1939 | Russia | Finland | Karelia (p); Salla (p); Rybachi; Gulf Islands | X |

| 1940 | Thailand | France | Indochina (p) | X |

| 1941 | Japan | Britain | Malaysia; Burma; Hong Kong | X |

| 1941 | Japan | Netherlands | Dutch East Indies | X |

| 1941 | Japan | United States | Philippines; Guam; Wake Island | X |

| 1941 | Peru | Ecuador* | Marañón | |

| 1952 | Bulgaria | Greece | Gamma Island | |

| 1952 | Saudi Arabia | Britain* | Buraimi | |

| 1954 | Thailand | Cambodia | Preah Vihear | |

| 1954 | South Korea | Japan | Dokdo (Takeshima) Islands | |

| 1954 | India | Portugal | Dadra; Nagar Haveli | |

| 1956 | Israel | Egypt | Sinai; Gaza | X |

| 1957 | Nicaragua | Honduras* | Mocoron | |

| 1957 | Morocco | Spain | Ifni (p) | |

| 1958 | Egypt | Sudan | Hala'ib Triangle | |

| 1959 | India | China* | Longju; Kongka Pass | |

| 1961 | India | Portugal | Goa | |

| 1962 | India | China* | Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh borders (p) | X |

| 1963 | Morocco | Algeria | Colomb-Bechar; Tindouf | |

| 1965 | Pakistan | India* | Rann of Kutch (p) | |

| 1965 | Pakistan | India | Akhnur | X |

| 1966 | Venezuela | Guyana | Ankoko Island | |

| 1967 | Israel | Egypt | Sinai; Gaza | X |

| 1969 | Argentina | Uruguay | Timoteo Dominguez (Punta Bauza) | |

| 1969 | El Salvador | Honduras | Gulf of Fonseca islands; six border pockets | X |

| 1969 | China | Russia* | Damansky (Zhenbao) Island | |

| 1969 | Iraq | Kuwait | Strip along border near Umm Qasr | |

| 1969 | South Yemen | Saudi Arabia* | Al-Wadiah | |

| 1971 | Iran | UAE | Abu Musa; G. and L. Tunbs | |

| 1971 | Philippines | China | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1972 | North Yemen | South Yemen | Kamaran | |

| 1973 | Egypt | Israel | Sinai (p) | X |

| 1973 | Syria | Israel | Golan Heights (p) | X |

| 1974 | China | South Vietnam* | Paracel Islands | |

| 1974 | Turkey | Cyprus | Northern Cyprus | X |

| 1975 | Cambodia | Vietnam* | Phu Quoc; Tho Chu; Poulo Wai | |

| 1975 | Morocco | Spain | Western Sahara | |

| 1977 | Somalia | Ethiopia* | Ogaden | X |

| 1977 | Cambodia | Vietnam | Tay Ninh; Ha Tien; adjacent areas | X |

| 1978 | Uganda | Tanzania | Kagera Salient | X |

| 1980 | Iraq | Iran | Khuzestan | X |

| 1981 | Ecuador | Peru* | Cordillera del Condor (p) | |

| 1982 | Argentina | Britain* | Falkland (Malvinas) Islands | X |

| 1983 | Nigeria | Chad* | Islands in Lake Chad | |

| 1983 | Malaysia | Vietnam | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1984 | India | Pakistan | Siachen | |

| 1984 | Laos | Thailand | Three-Village Border Region | |

| 1984 | India | China | Thag La | |

| 1985 | Mali | Burkina Faso | Agacher Strip | |

| 1986 | China | India | Thag La | |

| 1986 | Qatar | Bahrain | Fasht al-Dibal | |

| 1987 | Thailand | Laos* | Three-Village Border Region | |

| 1987 | Nigeria | Cameroon | Islands in Lake Chad | |

| 1988 | China | Vietnam* | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1991 | Botswana | Namibia | Kasikili/Sududo Island | |

| 1991 | Armenia | Azerbaijan | Nagorno-Karabakh; adjacent regions | X |

| 1993 | Nigeria | Cameroon | Diamant; Jabane; Bakassi | |

| 1994 | China | Philippines | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1994 | Egypt | Sudan | Hala'ib Triangle | |

| 1995 | Ecuador | Peru* | Cenepa (p) | X |

| 1995 | Eritrea | Yemen | Hanish Islands | |

| 1996 | Greece | Turkey* | Imia (Kardak); Akrogialia | |

| 1998 | Eritrea | Ethiopia* | Badme | X |

| 1999 | Pakistan | India* | Kargil | X |

| 2002 | Morocco | Spain* | Parsley (Perejil) Island | |

| 2008 | Djibouti | Eritrea | Ras Doumeira (p) | |

| 2010 | Nicaragua | Costa Rica | Calero Island (p) | |

| 2014 | Russia | Ukraine | Crimea | |

| . | Land Grab . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year . | By . | Against . | Territory . | War . |

| 1919 | Romania | Russia | Bessarabia | |

| 1919 | Finland | Russia* | East Karelia (p) | |

| 1921 | Costa Rica | Panama* | Coto | |

| 1921 | Yugoslavia | Albania | Northern Albania | |

| 1922 | Turkey | Britain | Chanak | |

| 1923 | Italy | Greece | Corfu | |

| 1925 | Russia | Afghanistan | Urta-Tugai | |

| 1927 | Norway | Britain | Bouvet Island | |

| 1928 | Paraguay | Bolivia* | Chaco (p) | |

| 1931 | Japan | China | Manchuria | X |

| 1932 | Bolivia | Paraguay* | Chaco (p) | X |

| 1932 | Peru | Colombia* | Leticia | |

| 1933 | North Yemen | Saudi Arabia* | Najran (Asir) | X |

| 1937 | Russia | Japan | Amur River Islands | |

| 1938 | Russia | Japan | Changkufeng | X |

| 1939 | Japan | Russia* | Nomonhan | X |

| 1939 | Russia | Finland | Karelia (p); Salla (p); Rybachi; Gulf Islands | X |

| 1940 | Thailand | France | Indochina (p) | X |

| 1941 | Japan | Britain | Malaysia; Burma; Hong Kong | X |

| 1941 | Japan | Netherlands | Dutch East Indies | X |

| 1941 | Japan | United States | Philippines; Guam; Wake Island | X |

| 1941 | Peru | Ecuador* | Marañón | |

| 1952 | Bulgaria | Greece | Gamma Island | |

| 1952 | Saudi Arabia | Britain* | Buraimi | |

| 1954 | Thailand | Cambodia | Preah Vihear | |

| 1954 | South Korea | Japan | Dokdo (Takeshima) Islands | |

| 1954 | India | Portugal | Dadra; Nagar Haveli | |

| 1956 | Israel | Egypt | Sinai; Gaza | X |

| 1957 | Nicaragua | Honduras* | Mocoron | |

| 1957 | Morocco | Spain | Ifni (p) | |

| 1958 | Egypt | Sudan | Hala'ib Triangle | |

| 1959 | India | China* | Longju; Kongka Pass | |

| 1961 | India | Portugal | Goa | |

| 1962 | India | China* | Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh borders (p) | X |

| 1963 | Morocco | Algeria | Colomb-Bechar; Tindouf | |

| 1965 | Pakistan | India* | Rann of Kutch (p) | |

| 1965 | Pakistan | India | Akhnur | X |

| 1966 | Venezuela | Guyana | Ankoko Island | |

| 1967 | Israel | Egypt | Sinai; Gaza | X |

| 1969 | Argentina | Uruguay | Timoteo Dominguez (Punta Bauza) | |

| 1969 | El Salvador | Honduras | Gulf of Fonseca islands; six border pockets | X |

| 1969 | China | Russia* | Damansky (Zhenbao) Island | |

| 1969 | Iraq | Kuwait | Strip along border near Umm Qasr | |

| 1969 | South Yemen | Saudi Arabia* | Al-Wadiah | |

| 1971 | Iran | UAE | Abu Musa; G. and L. Tunbs | |

| 1971 | Philippines | China | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1972 | North Yemen | South Yemen | Kamaran | |

| 1973 | Egypt | Israel | Sinai (p) | X |

| 1973 | Syria | Israel | Golan Heights (p) | X |

| 1974 | China | South Vietnam* | Paracel Islands | |

| 1974 | Turkey | Cyprus | Northern Cyprus | X |

| 1975 | Cambodia | Vietnam* | Phu Quoc; Tho Chu; Poulo Wai | |

| 1975 | Morocco | Spain | Western Sahara | |

| 1977 | Somalia | Ethiopia* | Ogaden | X |

| 1977 | Cambodia | Vietnam | Tay Ninh; Ha Tien; adjacent areas | X |

| 1978 | Uganda | Tanzania | Kagera Salient | X |

| 1980 | Iraq | Iran | Khuzestan | X |

| 1981 | Ecuador | Peru* | Cordillera del Condor (p) | |

| 1982 | Argentina | Britain* | Falkland (Malvinas) Islands | X |

| 1983 | Nigeria | Chad* | Islands in Lake Chad | |

| 1983 | Malaysia | Vietnam | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1984 | India | Pakistan | Siachen | |

| 1984 | Laos | Thailand | Three-Village Border Region | |

| 1984 | India | China | Thag La | |

| 1985 | Mali | Burkina Faso | Agacher Strip | |

| 1986 | China | India | Thag La | |

| 1986 | Qatar | Bahrain | Fasht al-Dibal | |

| 1987 | Thailand | Laos* | Three-Village Border Region | |

| 1987 | Nigeria | Cameroon | Islands in Lake Chad | |

| 1988 | China | Vietnam* | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1991 | Botswana | Namibia | Kasikili/Sududo Island | |

| 1991 | Armenia | Azerbaijan | Nagorno-Karabakh; adjacent regions | X |

| 1993 | Nigeria | Cameroon | Diamant; Jabane; Bakassi | |

| 1994 | China | Philippines | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1994 | Egypt | Sudan | Hala'ib Triangle | |

| 1995 | Ecuador | Peru* | Cenepa (p) | X |

| 1995 | Eritrea | Yemen | Hanish Islands | |

| 1996 | Greece | Turkey* | Imia (Kardak); Akrogialia | |

| 1998 | Eritrea | Ethiopia* | Badme | X |

| 1999 | Pakistan | India* | Kargil | X |

| 2002 | Morocco | Spain* | Parsley (Perejil) Island | |

| 2008 | Djibouti | Eritrea | Ras Doumeira (p) | |

| 2010 | Nicaragua | Costa Rica | Calero Island (p) | |

| 2014 | Russia | Ukraine | Crimea | |

Notes: *The initial land grab provoked an immediate retaliatory land grab by this state. (p) The land grab seized only part of the named territory.

Land grabs, 1918–2016

| . | Land Grab . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year . | By . | Against . | Territory . | War . |

| 1919 | Romania | Russia | Bessarabia | |

| 1919 | Finland | Russia* | East Karelia (p) | |

| 1921 | Costa Rica | Panama* | Coto | |

| 1921 | Yugoslavia | Albania | Northern Albania | |

| 1922 | Turkey | Britain | Chanak | |

| 1923 | Italy | Greece | Corfu | |

| 1925 | Russia | Afghanistan | Urta-Tugai | |

| 1927 | Norway | Britain | Bouvet Island | |

| 1928 | Paraguay | Bolivia* | Chaco (p) | |

| 1931 | Japan | China | Manchuria | X |

| 1932 | Bolivia | Paraguay* | Chaco (p) | X |

| 1932 | Peru | Colombia* | Leticia | |

| 1933 | North Yemen | Saudi Arabia* | Najran (Asir) | X |

| 1937 | Russia | Japan | Amur River Islands | |

| 1938 | Russia | Japan | Changkufeng | X |

| 1939 | Japan | Russia* | Nomonhan | X |

| 1939 | Russia | Finland | Karelia (p); Salla (p); Rybachi; Gulf Islands | X |

| 1940 | Thailand | France | Indochina (p) | X |

| 1941 | Japan | Britain | Malaysia; Burma; Hong Kong | X |

| 1941 | Japan | Netherlands | Dutch East Indies | X |

| 1941 | Japan | United States | Philippines; Guam; Wake Island | X |

| 1941 | Peru | Ecuador* | Marañón | |

| 1952 | Bulgaria | Greece | Gamma Island | |

| 1952 | Saudi Arabia | Britain* | Buraimi | |

| 1954 | Thailand | Cambodia | Preah Vihear | |

| 1954 | South Korea | Japan | Dokdo (Takeshima) Islands | |

| 1954 | India | Portugal | Dadra; Nagar Haveli | |

| 1956 | Israel | Egypt | Sinai; Gaza | X |

| 1957 | Nicaragua | Honduras* | Mocoron | |

| 1957 | Morocco | Spain | Ifni (p) | |

| 1958 | Egypt | Sudan | Hala'ib Triangle | |

| 1959 | India | China* | Longju; Kongka Pass | |

| 1961 | India | Portugal | Goa | |

| 1962 | India | China* | Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh borders (p) | X |

| 1963 | Morocco | Algeria | Colomb-Bechar; Tindouf | |

| 1965 | Pakistan | India* | Rann of Kutch (p) | |

| 1965 | Pakistan | India | Akhnur | X |

| 1966 | Venezuela | Guyana | Ankoko Island | |

| 1967 | Israel | Egypt | Sinai; Gaza | X |

| 1969 | Argentina | Uruguay | Timoteo Dominguez (Punta Bauza) | |

| 1969 | El Salvador | Honduras | Gulf of Fonseca islands; six border pockets | X |

| 1969 | China | Russia* | Damansky (Zhenbao) Island | |

| 1969 | Iraq | Kuwait | Strip along border near Umm Qasr | |

| 1969 | South Yemen | Saudi Arabia* | Al-Wadiah | |

| 1971 | Iran | UAE | Abu Musa; G. and L. Tunbs | |

| 1971 | Philippines | China | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1972 | North Yemen | South Yemen | Kamaran | |

| 1973 | Egypt | Israel | Sinai (p) | X |

| 1973 | Syria | Israel | Golan Heights (p) | X |

| 1974 | China | South Vietnam* | Paracel Islands | |

| 1974 | Turkey | Cyprus | Northern Cyprus | X |

| 1975 | Cambodia | Vietnam* | Phu Quoc; Tho Chu; Poulo Wai | |

| 1975 | Morocco | Spain | Western Sahara | |

| 1977 | Somalia | Ethiopia* | Ogaden | X |

| 1977 | Cambodia | Vietnam | Tay Ninh; Ha Tien; adjacent areas | X |

| 1978 | Uganda | Tanzania | Kagera Salient | X |

| 1980 | Iraq | Iran | Khuzestan | X |

| 1981 | Ecuador | Peru* | Cordillera del Condor (p) | |

| 1982 | Argentina | Britain* | Falkland (Malvinas) Islands | X |

| 1983 | Nigeria | Chad* | Islands in Lake Chad | |

| 1983 | Malaysia | Vietnam | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1984 | India | Pakistan | Siachen | |

| 1984 | Laos | Thailand | Three-Village Border Region | |

| 1984 | India | China | Thag La | |

| 1985 | Mali | Burkina Faso | Agacher Strip | |

| 1986 | China | India | Thag La | |

| 1986 | Qatar | Bahrain | Fasht al-Dibal | |

| 1987 | Thailand | Laos* | Three-Village Border Region | |

| 1987 | Nigeria | Cameroon | Islands in Lake Chad | |

| 1988 | China | Vietnam* | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1991 | Botswana | Namibia | Kasikili/Sududo Island | |

| 1991 | Armenia | Azerbaijan | Nagorno-Karabakh; adjacent regions | X |

| 1993 | Nigeria | Cameroon | Diamant; Jabane; Bakassi | |

| 1994 | China | Philippines | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1994 | Egypt | Sudan | Hala'ib Triangle | |

| 1995 | Ecuador | Peru* | Cenepa (p) | X |

| 1995 | Eritrea | Yemen | Hanish Islands | |

| 1996 | Greece | Turkey* | Imia (Kardak); Akrogialia | |

| 1998 | Eritrea | Ethiopia* | Badme | X |

| 1999 | Pakistan | India* | Kargil | X |

| 2002 | Morocco | Spain* | Parsley (Perejil) Island | |

| 2008 | Djibouti | Eritrea | Ras Doumeira (p) | |

| 2010 | Nicaragua | Costa Rica | Calero Island (p) | |

| 2014 | Russia | Ukraine | Crimea | |

| . | Land Grab . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year . | By . | Against . | Territory . | War . |

| 1919 | Romania | Russia | Bessarabia | |

| 1919 | Finland | Russia* | East Karelia (p) | |

| 1921 | Costa Rica | Panama* | Coto | |

| 1921 | Yugoslavia | Albania | Northern Albania | |

| 1922 | Turkey | Britain | Chanak | |

| 1923 | Italy | Greece | Corfu | |

| 1925 | Russia | Afghanistan | Urta-Tugai | |

| 1927 | Norway | Britain | Bouvet Island | |

| 1928 | Paraguay | Bolivia* | Chaco (p) | |

| 1931 | Japan | China | Manchuria | X |

| 1932 | Bolivia | Paraguay* | Chaco (p) | X |

| 1932 | Peru | Colombia* | Leticia | |

| 1933 | North Yemen | Saudi Arabia* | Najran (Asir) | X |

| 1937 | Russia | Japan | Amur River Islands | |

| 1938 | Russia | Japan | Changkufeng | X |

| 1939 | Japan | Russia* | Nomonhan | X |

| 1939 | Russia | Finland | Karelia (p); Salla (p); Rybachi; Gulf Islands | X |

| 1940 | Thailand | France | Indochina (p) | X |

| 1941 | Japan | Britain | Malaysia; Burma; Hong Kong | X |

| 1941 | Japan | Netherlands | Dutch East Indies | X |

| 1941 | Japan | United States | Philippines; Guam; Wake Island | X |

| 1941 | Peru | Ecuador* | Marañón | |

| 1952 | Bulgaria | Greece | Gamma Island | |

| 1952 | Saudi Arabia | Britain* | Buraimi | |

| 1954 | Thailand | Cambodia | Preah Vihear | |

| 1954 | South Korea | Japan | Dokdo (Takeshima) Islands | |

| 1954 | India | Portugal | Dadra; Nagar Haveli | |

| 1956 | Israel | Egypt | Sinai; Gaza | X |

| 1957 | Nicaragua | Honduras* | Mocoron | |

| 1957 | Morocco | Spain | Ifni (p) | |

| 1958 | Egypt | Sudan | Hala'ib Triangle | |

| 1959 | India | China* | Longju; Kongka Pass | |

| 1961 | India | Portugal | Goa | |

| 1962 | India | China* | Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh borders (p) | X |

| 1963 | Morocco | Algeria | Colomb-Bechar; Tindouf | |

| 1965 | Pakistan | India* | Rann of Kutch (p) | |

| 1965 | Pakistan | India | Akhnur | X |

| 1966 | Venezuela | Guyana | Ankoko Island | |

| 1967 | Israel | Egypt | Sinai; Gaza | X |

| 1969 | Argentina | Uruguay | Timoteo Dominguez (Punta Bauza) | |

| 1969 | El Salvador | Honduras | Gulf of Fonseca islands; six border pockets | X |

| 1969 | China | Russia* | Damansky (Zhenbao) Island | |

| 1969 | Iraq | Kuwait | Strip along border near Umm Qasr | |

| 1969 | South Yemen | Saudi Arabia* | Al-Wadiah | |

| 1971 | Iran | UAE | Abu Musa; G. and L. Tunbs | |

| 1971 | Philippines | China | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1972 | North Yemen | South Yemen | Kamaran | |

| 1973 | Egypt | Israel | Sinai (p) | X |

| 1973 | Syria | Israel | Golan Heights (p) | X |

| 1974 | China | South Vietnam* | Paracel Islands | |

| 1974 | Turkey | Cyprus | Northern Cyprus | X |

| 1975 | Cambodia | Vietnam* | Phu Quoc; Tho Chu; Poulo Wai | |

| 1975 | Morocco | Spain | Western Sahara | |

| 1977 | Somalia | Ethiopia* | Ogaden | X |

| 1977 | Cambodia | Vietnam | Tay Ninh; Ha Tien; adjacent areas | X |

| 1978 | Uganda | Tanzania | Kagera Salient | X |

| 1980 | Iraq | Iran | Khuzestan | X |

| 1981 | Ecuador | Peru* | Cordillera del Condor (p) | |

| 1982 | Argentina | Britain* | Falkland (Malvinas) Islands | X |

| 1983 | Nigeria | Chad* | Islands in Lake Chad | |

| 1983 | Malaysia | Vietnam | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1984 | India | Pakistan | Siachen | |

| 1984 | Laos | Thailand | Three-Village Border Region | |

| 1984 | India | China | Thag La | |

| 1985 | Mali | Burkina Faso | Agacher Strip | |

| 1986 | China | India | Thag La | |

| 1986 | Qatar | Bahrain | Fasht al-Dibal | |

| 1987 | Thailand | Laos* | Three-Village Border Region | |

| 1987 | Nigeria | Cameroon | Islands in Lake Chad | |

| 1988 | China | Vietnam* | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1991 | Botswana | Namibia | Kasikili/Sududo Island | |

| 1991 | Armenia | Azerbaijan | Nagorno-Karabakh; adjacent regions | X |

| 1993 | Nigeria | Cameroon | Diamant; Jabane; Bakassi | |

| 1994 | China | Philippines | Spratly Islands (p) | |

| 1994 | Egypt | Sudan | Hala'ib Triangle | |

| 1995 | Ecuador | Peru* | Cenepa (p) | X |

| 1995 | Eritrea | Yemen | Hanish Islands | |

| 1996 | Greece | Turkey* | Imia (Kardak); Akrogialia | |

| 1998 | Eritrea | Ethiopia* | Badme | X |

| 1999 | Pakistan | India* | Kargil | X |

| 2002 | Morocco | Spain* | Parsley (Perejil) Island | |

| 2008 | Djibouti | Eritrea | Ras Doumeira (p) | |

| 2010 | Nicaragua | Costa Rica | Calero Island (p) | |

| 2014 | Russia | Ukraine | Crimea | |

Notes: *The initial land grab provoked an immediate retaliatory land grab by this state. (p) The land grab seized only part of the named territory.

Whereas land grabs occurred fairly steadily throughout the 1918–2016 period, nine of the thirteen coerced cessions cluster. Coercion appears to have been unusually effective in the international climate that existed between 1937 and 1940, particularly in Eastern Europe. With the prospects of major war and outright conquest looming, small states made concessions that they might not have granted in other periods. Czechoslovakia and Romania were the primary victims, together accounting for half of the cessions.

The steady rate of land grabs since 1918 amends important findings by Zacher (2001), Fazal (2011), and Atzili (2012) that territorial conquest declined markedly over the course of the twentieth century. Each author attributes that reduction to a strengthening norm of territorial integrity. As Fazal underscores, attempts to conquer and absorb states in their entirety declined precipitously after 1945. However, as I explore elsewhere, land grabs seizing smaller pieces of territory have largely persisted.30 Conquest no longer goes hand in hand with warfare as part of a brute force strategy. Land grabs attempting to take smaller territories without provoking war as part of a fait accompli strategy are now the predominant form of territorial conquest. Conquest has not gone away, but rather has become smaller, more targeted, and less violent (Altman 2016).

There are a variety of ways to parse the exact ratio of land grabs to coerced cessions. Some reduce the disparity; others strengthen it. For instance, excluding acquisitions of entire states eliminates twenty-one conquests by (brute) force, but only four cessions.31 Conversely, including retaliatory land grabs inflates the number of land grabs. Nonetheless, this inclusion is appropriate. When a challenger takes a piece of a territory, the defender can seek to regain that territory by fait accompli or by coercion. Indeed, many victims of land grabs immediately demand withdrawal and back those demands with threats of force. These threats failed, except in the cases of Gamma Island (discussed above) and the Amur River Islands in 1937. Japanese threats succeeded at undoing that Soviet land grab. The absence of additional cases of coercion reversing land grabs offers relevant evidence that speaks to the rarity of coercive gains. Moreover, one might exclude retaliatory land grabs on the grounds that they are not fully independent observations. However, this same concern would justify removing a minimum of four of the remaining eleven coerced cessions. The disparity would remain.

The 112 to thirteen figure rests on defining land grabs and coerced cessions as forms of territorial acquisition, that is, as events that occur at single moments in time irrespective of what follows. It is, nonetheless, reasonable to ask what happens next. Of particular concern, this comparison excludes failed coercive threats but includes land grabs that succeeded at taking territory only to fail to retain control for long.

Wars and retaliatory land grabs provide the two leading reasons for the failure of land grabs to secure lasting gains. Table 2 lists both, with the final column utilizing Correlates of War data to identify interstate wars. Of the 112 land grabs, retaliatory land grabs account for twenty-eight (25 percent). Setting aside these retaliatory land grabs, twenty-seven (of eighty-four) initial land grabs erupted into wars that met the standard 1000 battle death criterion (32 percent).32 Some of these wars reversed land grabs.

In contrast, none of the coerced cessions led immediately to war or retaliatory land grabs. This accords with established theories. The success of coercion equates to the achievement of a war-avoiding bargain. However, most coerced cessions occurred during the turmoil that culminated in the Second World War. That war soon reversed most of those cessions.

Table 3 show that both strategies often failed to secure lasting gains. Land grabs and coerced cessions alike produce gains that remain after ten years only about half of the time. That success rate drops further for each when including only cases of uninterrupted control of the territory for ten years. This provides a better barometer of whether the land grab or coercive threat created the gain, rather than merely happening to precede it. The ten-year comparisons warrant some caution. Because so many cessions occurred during the pre-WWII cluster, the war may have deflated the long-term success rate of coercion.

The durability of territorial gains, 1918–2016

| . | Coerced cessions . | Land grabs . |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition (even if short-lived) | 13 | 112 |

| Held at end of militarized dispute | 13 | 59 |

| Held after 10 years | 7 | 56* |

| Held uninterrupted for 10 years | 5 | 47* |

| . | Coerced cessions . | Land grabs . |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition (even if short-lived) | 13 | 112 |

| Held at end of militarized dispute | 13 | 59 |

| Held after 10 years | 7 | 56* |

| Held uninterrupted for 10 years | 5 | 47* |

Note: *Cases after 2006 omitted.

The durability of territorial gains, 1918–2016

| . | Coerced cessions . | Land grabs . |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition (even if short-lived) | 13 | 112 |

| Held at end of militarized dispute | 13 | 59 |

| Held after 10 years | 7 | 56* |

| Held uninterrupted for 10 years | 5 | 47* |

| . | Coerced cessions . | Land grabs . |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition (even if short-lived) | 13 | 112 |

| Held at end of militarized dispute | 13 | 59 |

| Held after 10 years | 7 | 56* |

| Held uninterrupted for 10 years | 5 | 47* |

Note: *Cases after 2006 omitted.

The two strategies clearly differ in one respect: land grabs failed more quickly. By the end of the militarized dispute in which the land grab occurred, including any resultant crisis or war, defenders reversed half of the land grabs. Although a large reduction, note that even this revised ratio is approximately 1 to 4.5 in favor of the fait accompli. This figure would still represent a striking departure from conventional assumptions that coercion is of central importance for international politics while the fait accompli merits only occasional attention.

Territory changes hands in more ways than just coercion and the fait accompli. The two are the primary adversarial means by which states acquire territory at each other's expense short of war. They are the two ways to make gains in the thick of crises. Nonetheless, territory also changes hands at the ends of wars and—quite frequently—through negotiated agreements. Could these negotiated agreements be coercion?

To address this question, I examined all territorial cessions since 1918 irrespective of whether the cases appear as conflicts (compellent threats, crises, disputes, or wars) in the associated datasets.33 I observed that negotiated agreements to cede territory tend to occur years after a crisis or dispute—if any crisis or militarized dispute occurred at all—and without an explicit compellent threat. Even if coercion has occurred, it is qualitatively distinct from the sort of crisis bargaining in, for instance, the Munich Crisis. Moreover, the winning side has very often prevailed due to a favorable ruling by an international legal institution or arbitrator after a prolonged process of deliberation, which does not suggest coercion. The three strong candidates for latent coercion are the Spanish cession of Ifni to Morocco, the Israeli return of the Sinai to Egypt, and the British relinquishment of Hong Kong to China. Beyond those three, it becomes difficult to find cases where a convincing qualitative argument exists for latent coercion determining the outcome.

There are many ways to compare coercion to faits accomplis. Some produce a ratio less uneven than 112 to thirteen, but the bottom line remains unchanged. Although the international relations literature devotes far more attention to coercion, the fait accompli better accords with the modern history of territorial gains.

Questions Raised

The fait accompli deserves to emerge from the shadow of coercion and take on a major role in thinking about statecraft on the brink of war. In providing evidence to support that conclusion, this research note aims to provide an impetus to future research about the fait accompli. To aid in that endeavor, I conclude with a set of unanswered questions.

First, what does it mean for bargaining theories of war that, at least with respect to territory, explicit coercive bargains are so rare, while faits accomplis are more prevalent? How might these theories adapt to accommodate a central role for faits accomplis? A previous section considered this question in more detail. It explains why the answer depends on a different question: why are coerced cessions rare in comparison to land grabs? Given the implications of the likely answers, should compellent threats and signals of resolve retain their current prides of place in the literature's understanding of statecraft on the brink of war?

This study also underscores the need for a body of research directly studying faits accomplis. What does a theory of faits accomplis look like? Under what conditions are faits accomplis more likely to occur? Why, for instance, did Russia invade and annex Crimea in 2014 but pursue a less overt form of intervention in the Donbas region of Ukraine later that year? Reframed, the question becomes: when and how do states deter faits accomplis?

Third, under what conditions are faits accomplis likely to lead to war? The literature regards the fait accompli as a risky crisis tactic that makes war more likely. Yet, only a minority of land grabs lead to war. When can states successfully “get away” with faits accomplis? Senese and Vasquez (2008, 9–14) identify territorial disputes as a crucial initial “step to war.” Could the land grab belong as another? Some initiators in wars over territory eschew the fait accompli and proceed directly to brute force. Nonetheless, in many other cases like the Falklands, a miscalculated fait accompli served as an essential penultimate stage in the escalation of a territorial dispute to war.

Fourth, when and how do challengers profit from their faits accomplis? When and how can defenders reverse them? Can they do so without fighting and winning a war? The frequency of retaliatory land grabs hints at a complex strategic interaction as states respond to faits accomplis.

Fifth, are faits accomplis as prevalent with respect to disputes not involving territory? More likely, it varies by issue type. Occupying and holding territory involve fundamental functions of militaries, so military force may fit territorial disputes better than, for instance, economic disputes (Huth 2000, 101). For some issue areas, states cannot choose the fait accompli as a policy option. States that wish for diplomatic recognition from an adversary inherently cannot impose that recognition by fait accompli. The same holds for states seeking to influence an adversary to cease supporting rebels. By their nature, these concessions must be given, not taken. In other issue areas, however, faits accomplis occur more frequently. Examples include, on the one hand, building the next stage in a nuclear program in defiance of external pressure and, on the other hand, providing weapons to rebel groups. States do not demand consent for these activities. They simply conduct them. The issue of rebel support clarifies the distinction. States can easily provide support to a rebel group by fait accompli, but they will find it extremely difficult to prevent support for rebels by fait accompli. The latter requires coercion. This variation suggests another question: do challengers prevail more frequently in issue areas for which the fait accompli readily avails itself as a policy option?

Finally, the prevalence of gains by fait accompli entails practical implications for strategy, statecraft, and scenario planning. Consider the longstanding tensions over the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. Is China more likely to wrest control of islands now occupied by Vietnam or the Philippines by suddenly seizing them in a fait accompli? Or, alternatively, by issuing a coercive threat that cows one of its neighbors into agreeing to relinquish islands?34 In theory, China might pursue either approach. But only the former accords with how states have made territorial gains in recent decades. Similarly, Japanese efforts to prepare for a conflict with China over the disputed Senkaku Islands should focus on the scenario in which a phone rings one day with news that Chinese marines have occupied the islands. Even if China does attempt coercion, Japan can choose to disregard any verbal demand. The scenario of a potential Chinese land grab would then return to center stage. In large measure, avoiding a severe crisis or war in maritime East Asia boils down to the unique challenge of deterring a fait accompli in the form of an island grab.

For scholars, theoretical models of crises and the onset of war can better represent reality by explicitly integrating faits accomplis. For statesmen contemplating potential crises, it is vital to identify and prepare for potential adversary faits accomplis, both to deter them and to respond effectively if deterrence fails. When the issue is disputed territory, challengers have not struggled to identify the land grab as a strategic option. Nonetheless, the current foreign policy discourse has yet to recognize the land grab as one of the most probable and consequential threats facing the world today. It is time for the fait accompli to receive the attention it deserves as one of the principal tools of statecraft in international politics, on par with coercion.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information is available at the International Studies Quarterly data archive.

Footnotes

Schelling does discuss faits accomplis in other contexts later in the book (cited above).

From one perspective, the fait accompli closely resembles brute force. It makes gains by unilateral imposition rather than by concession. From another perspective, however, the fait accompli closely resembles coercion. After taking a gain, each fait accompli relies on a credible threat to deter the adversary from retaking what was lost or punishing its seizure. Per Schelling (1966), brute force and coercion are distinct alternatives, yet the fait accompli incorporates core elements of each. That one can plausibly conceptualize the fait accompli as either brute force or coercion (or, somehow, both) supports my claim that it is more useful to define it as a distinct strategy falling between the two.

For similar definitions, see (Schelling 1966, 44-45; Snyder and Diesing 1977, 227).

This creates a definitional oddity wherein a single action may be a fait accompli with respect to third parties but not with respect to the defender. Iraq's 1990 invasion and annexation of Kuwait was brute force (unlimited) with respect to Kuwait but a fait accompli with respect to the United States.

I include here both coercion by punishment and coercion by denial (Pape 1996).

Schelling (1966, 35–91) emphasized the greater difficulty of compellence in his original formulation of the deterrence-compellence dichotomy.

Also see Pape (1997) on this problem and economic sanctions.

Including surprise within the definition of fait accompli would leave no clear term for faits accomplis that eschew surprise. Those often occur immediately after the failure of coercive threats.

For a finer-grained discussion of types and degrees of surprise, see Betts (1982) and Wohlstetter (1962).

Unlike Tarar, my definition does not require a fait accompli to be intrinsically costly. I observe that many land grabs seize unoccupied territory at negligible intrinsic cost, with the costs instead depending on the responses of victims and third parties.

Intriguingly, and unlike most of the subsequent literature, Fearon (1995, 394, 405) models war-avoiding bargains using the term “fait accompli” (exactly twice). However, he uses the term to refer to making take-it-or-leave-it offers, which encompass both faits accomplis (by my definition) and coercive ultimatums. Therefore, he does not fully explore the distinction between coercion and the fait accompli.

Tarar (2016) formally integrates faits accomplis into the rationalist framework. Fey and Ramsay (2011) show that the framework is not especially dependent on assumptions about the exact bargaining protocol.

However, two other possible explanations for this discrepancy from outside the unitary rationalist framework might raise fewer questions about the importance of signaling resolve. Sensitive to their domestic political audience, leaders may find it less humiliating to lose territory to unilateral adversary action than to actively participating in a capitulation. Alternatively, perhaps states can better deny the legitimacy of a territorial loss if it occurs by fait accompli than if they consent to it.

Unfortunately, insufficient information concerning Moscow's strategic thinking has come to light to determine which, if any, of these explanations is correct. I leave the empirical question of why this disparity exists to future research. I suspect that the answer is a combination of these explanations.

My thanks to James Fearon for suggesting this explanation.

This screening may offer an alternative explanation for Sechser's (2010) finding that strong states struggle to coerce weak states. Strong states that forgo the opportunity for an initial fait accompli despite their clear power advantage may signal a particularly low level of resolve, undermining subsequent compellent threats.

It was not possible to apply the definition of land grabs during state formation processes. The salient criterion is the existence of a prior interstate border (including de facto borders). Without one, it proved infeasible to identify land grabs changing it. The omitted cases cluster in a few transitional periods: former Ottoman Empire 1910s, Eastern Europe 1910s, Israel-Palestine 1940s, India-Pakistan 1940s, and Balkans 1990s. These cases also blur the line between civil and interstate conflict.

Mearsheimer's (1983) limited aims strategy applies better to these cases than to land grabs generally.

Jones et al. 1996; Brecher and Wilkenfeld 1997; Tir, Schafer, and Diehl 1998; Diehl and Goertz 2002; Sarkees and Wayman 2010. I would like to thank Ken Schultz for providing case narratives on territorial MIDs. I also made more limited use of the ICOW Territorial Claims and Territorial Dispute datasets (Huth 1996; Hensel et al. 2008; Huth and Allee 2002).

Although the ICOW dataset includes “military conquest/occupation” as a mode of resolution of territorial claims, this category contains few land grabs (Hensel et al. 2008). Land grabs rarely result in the immediate termination of territorial claims. Consequently, brute force conquests of entire states account for many of these claims resolutions.

Zacher (2001) provides a list of “interstate territorial aggressions,” but it leaves out many land grabs because it selects on violence.

Both codebooks and datasets are available from the Correlates of War webpage. Also see Diehl and Goertz (2002, 53–54).

I exclude cases in which a coalition occupies the full territory of a state but one or more members of the coalition receive only a smaller piece (for example, Poland in 1939).

I found that challengers either try to get away with a limited gain—seeking to acquire only small pieces of a defender's territory—or accept that the defender will resist fully and aim for the full territory. Attempts to acquire, for instance, half of another state's territory are exceedingly rare. If the stakes are high enough that the defender will resist fully, there is little reason to limit war aims. This supports my conception of land grabs as faits accomplis and conquests of entire states as brute force.

Decolonization conflicts between imperial powers and groups representing occupied populations fall outside the scope of this study because they are not conflicts between two existing states. Many of these groups seem to have succeeded at coercing out the colonizing power. This raises questions of whether and why coercion was more successful in these conflicts.

Two further cases are open to interpretation: the Spanish decision to cede Western Sahara in 1975 and the Soviet withdrawal from portions of Iran in 1946. I code the former as a land grab due to the Green March and the latter as noncoercive.

A retaliatory land grab must meet two criteria: (1) The victim of a land grab responds with a limited operation to promptly retake a finite territory. (2) That operation must occur before the conflict has crossed the threshold to qualify as a war. If war is already underway (e.g., Israel's seizure of the West Bank and Golan Heights), that retaliation is not a land grab. Nor do larger retaliatory operations aimed at regime change or outright conquest (for example, Iran's invasion of Iraq in the Iran-Iraq War) qualify.

Fazal (2011, 53) notes this possibility.

These capitulations—Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—also cluster around the onset of the Second World War.

This rate of war aligns with the conceptualization of the fait accompli as a calculated risk. Because it is difficult to accurately perceive how much loss the adversary will tolerate, challengers sometimes overreach and provoke a strong response.

On the cessions data, see Diehl and Goertz (2002).

These are the first two scenarios for Biddle and Oelrich (2016, 15–16).

References

Author notes

Author's note: I would like to thank Noel Anderson, Mark Bell, Andrew Bertoli, Christopher Clary, Lynn Eden, James Fearon, Jeffrey Friedman, Taylor Fravel, Phil Haun, Nicholas Miller, Vipin Narang, Kenneth Oye, Barry Posen, Scott Sagan, Kenneth Schultz, the editors, and four anonymous reviewers for their comments and insights.