-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gregory A Kline, Ally P.H Prebtani, Alexander A Leung, Ernesto L Schiffrin, The Potential Role of Primary Care in Case Detection/Screening of Primary Aldosteronism, American Journal of Hypertension, Volume 30, Issue 12, December 2017, Pages 1147–1150, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpx064

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Endocrine hypertension, particularly primary aldosteronism (PA), was previously considered to account for less than 1% of all hypertension and was suspected only when patients presented with spontaneous hypokalemia. However, the last 20 years of PA research has now clearly shown that PA is not a rarity, but rather, may account for up to 13% of unselected hypertensive individuals and between 10% and 20% of those with resistant hypertension. Most of these patients do not have spontaneous hypokalemia. The population prevalence of PA likely far exceeds actual detection rates in routine clinical care. As PA represents one of the most common, potentially reversible causes of hypertension, and is associated with significant cardiovascular complications over the long term, it is clear that a pragmatic strategy for targeted case detection in primary care is needed.

The forthcoming 2017 update of the Hypertension Canada guidelines continue to adhere to the model of rigorous methodological evaluation of all pertinent published evidence across the field of hypertension. This annually updated process ensures that Canadian physicians have ongoing access to the best evidence-based practices in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension,1 one of the biggest public health concerns in the country.2 Primary care providers are tasked with providing the bulk of hypertension care and as such, hypertension guidelines must be crafted in a manner that is practical and applicable to all practice environments.

For more than 15 years, Hypertension Canada guidelines have included advice on the investigation of secondary or resistant hypertension that is often due to endocrine causes. The evidence base for investigation of endocrine hypertension is predominantly found in the specialty journals of hypertension, endocrinology, nephrology, or cardiology, and may not be familiar to the majority of practitioners seeing hypertensive patients. In addition to the yearly update of endocrine hypertension recommendations that the Hypertension Canada has produced, the Endocrine Society has produced very recent and detailed guidelines for both primary aldosteronism (PA)3 and pheochromocytoma4 that are comprehensive and highly useful for specialists but may not be practical for the primary care environment. A recent study looking at the application of the Endocrine Society guidelines for PA suggested very poor uptake among primary care practitioners possibly due to low visibility or overcomplexity.5

THE IMPORTANCE OF CONSIDERING PA IN HYPERTENSION

Endocrine hypertension, particularly PA, was previously considered to account for less than 1% of all hypertension and was suspected only when patients presented with spontaneous hypokalemia. However, the last 20 years of PA research has now clearly shown that PA is not a “rare bird”, but rather, may account for up to 13% of unselected hypertensive individuals6 and between 10% and 24% of those with resistant hypertension.7 Most of these patients do not have spontaneous hypokalemia8 and the absence of hypokalemia should not be construed as evidence against the potential diagnosis of PA. The population prevalence of PA likely far exceeds actual detection rates in routine clinical care. As a form of low renin hypertension, the identification of PA also permits the clinician to avoid potentially ineffective therapy with common drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta-blockers, and other drugs that inhibit renin action for their effect.9 Therefore, given that PA represents one of the most common, potentially reversible causes of hypertension, and is associated with significant cardiovascular complications over the long term, it is clear that a better strategy for targeted case detection in primary care is needed.

In the midst of this changing perspective on causes and investigation of hypertension, the Endocrine Hypertension subgroup of the Hypertension Canada Guidelines Task Force would like to comment upon the place of selective PA screening in a Canadian health care context. Large, prospective, outcome-based population studies of PA screening are lacking, and therefore, specific and graded population screening recommendations cannot presently be made. There are nevertheless several compelling reasons to consider promoting broader screening strategies, especially as it likely represents the most common reversible secondary cause of hypertension.

Studies now show that in comparison to essential hypertension, those with PA have a 4-fold higher risk of stroke, a 6-fold higher risk of myocardial infarction, and a 12-fold high risk of atrial fibrillation.10 Renal injury and albuminuria are more common and severe in PA11 and excess aldosterone, the mediator, appears to induce renal hyperfiltration injury, but may be missed because serum creatinine levels often remain within the normal range.12

Once diagnosed, PA may be treated either surgically or with targeted medical therapy, depending on subtype, usually with profound blood pressure improvement.13 This approach will often permit the reduction or cessation of other blood pressure lowering medications and such disease-specific treatment may also be associated with improved quality of life.14 Long-term, outcome-based trials of a PA screening and directed treatment approach are badly needed but in the interim, it is reasonable to believe that with such high population prevalence, there are likely to be real benefits from directed case finding and specific PA treatment.

Presented below is a list of clinical scenarios in which the practitioner should give consideration to the possible presence of PA. These scenarios are not necessarily mutually exclusive and in many cases, resistant hypertension may be present. These scenarios include:

Uncontrolled hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg) despite use of 3 drugs, including a thiazide diuretic

Hypertension requiring 4 or more drugs for adequate control <140/90 mm Hg

Hypertension with easily provoked thiazide—induced hypokalemia

Spontaneous hypokalemia with hypertension

Hypertension with blood pressure >150/100 mm Hg

Hypertension with known (sometimes incidental) adrenal mass

Hypertension with a family history of PA

Hypertension associated with obstructive sleep apnea*

*as recommended by the Endocrine Society Guidelines3 although not yet included in Hypertension Canada guidelines pending further supporting data.

Most of these scenarios are drawn from studies showing an increased prevalence of PA or strong correlations with plasma aldosterone.3,15,16 Retrospective studies of outcomes in PA suggest a possible higher rate of medication-free normotension among those who are diagnosed and definitively treated at a younger age, particularly women.17 Thus, while screening for secondary hypertension is already recommended in younger patients with hypertension, it may be particularly relevant to consider PA, even without the traditional clue of hypokalemia.

COMPLEXITIES AND LIMITATIONS TO BROADER SCREENING FOR PA IN PRIMARY CARE

The screening test of choice remains measurement of the plasma aldosterone-to-renin ratio (ARR). This widely available test has long been used for PA case detection and recommended by Hypertension Canada1 but may not be commonly considered in primary care despite numerous reports of its successful implementation in primary care settings.18–20 The basic premise of the ARR is that aldosterone secretion may be deemed to be inappropriate when plasma renin (which via angiotensin generation normally stimulates aldosterone release) is low or even undetectable. Although ingenious in concept, the ARR is also potentially complex in interpretation, which may have limited its translation to broader use. ARR results may be affected by inappropriate patient preparation, patients ingesting a typically recommended low salt diet21 age, renal function, several antihypertensive medications,22 and laboratory methodological considerations,23,24 including variation in the reporting units, which may generate extensive confusion between the literature, laboratory and patient results. Even using a standardized approach, the literature is inconsistent in its reporting of diagnostic ARR cutoffs. The Endocrine Society guidelines list a 13-step approach to the measurement of the ARR,3 which is likely to be impractical for use outside of specialty hypertension clinics and research settings.

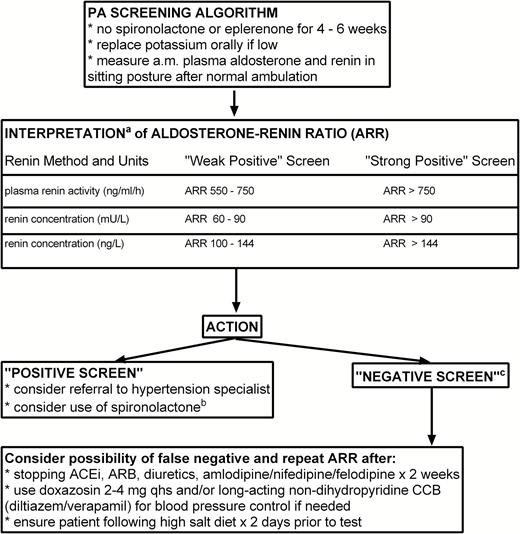

For these reasons, routine use of the ARR, while recommended, has perhaps been perceived as a challenging screening test to use and interpret for many front-line care providers. At the same time, as mentioned above, PA is probably too common to ignore any longer and a suitable compromise of accuracy and pragmatism is needed for selected case finding, which will largely remain in the realm of primary care practitioners. A reasonable and simplified approach to PA screening and ARR measurement (in sitting posture, after ambulation) is outlined in Figure 1.

Suggested approach to PA screening and ARR interpretation in primary care. aInterpretation of ARR is dependent upon the local laboratory method for renin measurement but assumes standard reporting of Aldosterone in pmol/l. bSpironolactone should be considered as medical management particularly in patients who are not deemed to be surgical adrenalectomy candidates. We suggest discontinuation of any ACEi or ARB prior to starting spironolactone therapy; careful follow up of serum creatinine and potassium is advised. cA “Negative Screen” may be a true negative or false negative. Drug interference is the most common reason for false negative ARR results and so repeat screening after drug adjustment may be required depending upon clinical suspicion. Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; PA, primary aldosteronism.

The values informing these suggestions are based on the desire to enable selective case finding by using an approach that is both simple and likely to have high sensitivity (low false-negative rate) for PA detection, to ensure that possible PA cases are found and brought forward for further investigation. The trade-off will be that specificity may be suboptimal (higher false positive rate). Because specificity is higher with higher ARR results, we have also included simple suggested cutoffs that help alert the physician to situations where PA is “possible” (“weak positive”) or even “probable” (“strong positive”). Based upon the patient’s clinical features, treatment goals and preferences, the screening physician may thus decide about possible referral to a specialty hypertension clinic also taking into account whether PA is “possible” or “probable.” Following referral to a hypertension specialty clinic/specialist, diagnostic/confirmatory tests exist that will assist interested or subspecialty physicians differentiate true positive from false positive PA diagnoses; details pertaining to the conduct and interpretation of such tests are well described in other specific endocrine hypertension-PA guidelines.3 Some patients will also need adrenal vein sampling prior to surgery, a diagnostic service now routinely available in many Canadian provinces. It is hoped that careful selection of cases for screening and adoption of a more “probability”-based understanding of the ARR will permit both improved PA case detection while ensuring a judicious use of specialty hypertension resources.

It is critical that clinical biochemistry laboratories play a role in this approach. Individual levels and reference ranges for plasma aldosterone is of little use (although the finding of a very high renin level virtually excludes surgical PA by itself25). Laboratories are therefore encouraged to institute reflex testing whereby an order for aldosterone is automatically converted to an order for both aldosterone and renin. Result reporting should give an interpretive range for ARR rather than the individual components and it may be useful for such laboratories to consider adopting the approach outlined above for “possible” or “probable” PA.26 This would help to ensure that PA cases are not missed on account of inability to put random aldosterone levels or ARR measures into clinical context. Locally validated ARR data are always preferred but if unavailable, it would be reasonable to adopt the Hypertension Canada cutoffs that coincide with the local assay methodology.

Referral to a hypertension specialist or endocrinologist should be considered for patients who have an elevated ARR and it may be of value to have tertiary care centers designate at least one clinic to act as a PA resource. It should be noted that, in the presence of hypertension and hypokalemia, the probability of PA is so high that referral is indicated, even with normal ARR since false negatives do occur. The hypertension specialist may choose to repeat the ARR under the more strict testing conditions or may choose to do a confirmatory test to ensure a correct diagnosis of PA. Patients who are suitable and agreeable to possible adrenalectomy may undergo computed tomography imaging and adrenal vein sampling. Patients less suitable or unwilling for surgery may be treated empirically with rigorous sodium restriction and a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist such as spironolactone or eplerenone after careful consideration of their risks for hyperkalemia.27

The overriding principle of the Hypertension Canada guidelines is to promote the early detection and treatment of hypertension in Canada to reduce the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. It is hoped that the broader understanding of hypertension subtypes will facilitate early diagnosis and selection of disease-specific therapy. Population studies that examine the value of broader PA screening will be needed to move us one step closer to the intersection of personalized medicine and hypertension where needed.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

A.A.L. is supported by the Hypertension Canada New Investigator Award. E.L.S. is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair funded by the CIHR/Government of Canada program and a CIHR First Pilot Foundation Grant 332675. All of the authors contributed substantially to the design and writing of the manuscript. G.A.K. drafted the article. All of the authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectually important content, approved the final version submitted for publication, and agreed to act as guarantors of the work. This manuscript was sent to Guest Editor, Theodore A. Kotchen, MD, for editorial handling and final disposition.

REFERENCES