Abstract

The issue of insurance fraud by consumers continues to perplex insurance firms, costing billions of dollars per year in the United States alone. Some analysts report that 10 per cent or more of property/casualty insurance claims are fraudulent, while less than 20 per cent of fraudulent claims being detected. Consumer attitudes are becoming more tolerant of insurance fraud in recent years. Recognizing that not all insurance fraud situations are created equal, we investigate variability in perceptions of moral intensity in dissimilar insurance padding situations in a 2 (to help others versus to profit self) × 2 (a small credit union versus a large online insurer) model and compared the results between two independent samples (college students/Millennials and an older adult population). We also investigated the impact of ethical predispositions (formalism and utilitarianism) on moral awareness and moral judgment using these four scenarios. The results suggest that the Millennials may exhibit more situationalism and more lenient judgments of collaborative versus unilateral ethical violations. In particular, ‘for self’ versus ‘for others’ comparisons show striking differences between the two age groups. The results add to the growing literature in explaining intra-personal variability in moral decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Accenture (2010) More than Half of U.S. Consumers Say Poor Service Leads to Fraudulent Insurance Claims, Accenture Survey Finds. 1-2, http://newsroom.accenture.com/article_display.cfm?article_id¼5061, accessed 3 November 2015.

Agarwal, S., Driscoll, J.C., Gabaix, X. and Laibson, D. (2009) The age of reason: Financial decisions over the life-cycle with implications for regulation. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4554335, accessed 3 November, 2015.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) (2002) Consideration of fraud in a financial statement audit. AICPA, New York. October.

Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W. (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 103 (3): 411–423.

Arnold, T.J., Landry, T.D. and Reynolds, J.K. (2007) Retail online assurances: Typology development and empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 15 (4): 299–313.

Bandura, A. (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Brady, F.N. and Wheeler, G.E. (1996) An empirical study of ethical predispositions. Journal of Business Ethics 15 (9): 927–940.

Coalition against Insurance Fraud (CAIF) (2012) How big is $80 billion? http://www.insurancefraud.org/80-billion.htm, accessed 16 January 2013.

Collins, J.W. (1994) Is business ethics an oxymoron? Business Horizons 37 (5): 1–8.

Cressey, D.R. (1953) Other People’s Money. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Dehghanpour, A. and Rezvani, Z. (2015) The profile of unethical insurance customers: A European perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing 33 (3): 298–315.

Derrig, R.A. (2002) Insurance fraud. Journal of Risk and Insurance 69 (3): 271–287.

Farashah, A.D. and Estelami, H. (2014) The interplay of external punishment and internal rewards: An exploratory study of insurance fraud. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 19 (4): 253–264.

Ferrell, O.C. and Gresham, L.G. (1985) A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Marketing 49 (3): 87–96.

Festinger, L. (1957) A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row Peterson & Co.

Festinger, L. (ed.) (1962) An introduction to the theory of dissonance. In: A theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fointiat, V. (1998) Rationalization in act and problematic behaviour justification. European Journal of Social Psychology 28 (3): 471–474.

Frankena, W. (1963) Ethics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gepp, A.J., Wilson, H., Kumar, K. and Bhattacharya, S. (2012) A comprehensive analysis of decision trees vis-à-vis other computational data mining techniques in automotive insurance fraud detection. Journal of Data Science 10 (3): 537–561.

Gilligan, C. (1982) In a Different Voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Herrero, C., Tomás, J. and Villar, A. (2006) Decision theories and probabilistic insurance: An experimental test. Spanish Economic Review 8: 35–52.

Hsee, C.K. and Kunreuther, H.C. (2000) The action effect in insurance decision. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 20 (2): 141–159.

Hunt, S. D. and Vitell, S. (1986) A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing 6 (Spring): 5–16.

Insurance Council of New Zealand (2014) Insurance Fraud, http://www.icnz.org.nz/for-consumers/insurance-fraud/, accessed 7 October 2015.

Insurance Information Institute (2008) Fact Statistics: Fraud, http://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/fraud, accessed 3 November 2015.

International Association of Financial Management (2015) Insurance Fraud: Expert Insights May 2015 (Part I), http://www.interfima.org/publications/insurance-fraud-expert-insights-may-2015-part/, accessed 6 October 2015.

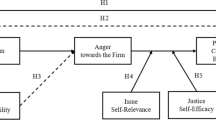

Jones, T.M. (1991) Ethical decision making in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review 16 (2): 366–395.

Jones, T.M. and Huber, V.L. (1992) Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review 16 (2): 366–395.

Kaplan, U., Crockett, C.E. and Tivnan, T. (2014) Moral motivation of college students through multiple developmental structures: Evidence of intrapersonal variability in a complex dynamic system. Motivation & Emotion 38 (3): 336–352.

Lesch, W.C. and Byars, B. (2008) Consumer insurance fraud in the US property-casualty industry. Journal of Finance Crime 15 (4): 411–431.

Murphy, P.R. (2012) Attitude, Machiavellianism and the rationalization of misreporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society 37 (4): 242–259.

Murphy, P.R. and Dacin, M.T. (2011) Psychological pathways to fraud: Understanding and preventing fraud in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics 101 (4): 601–618.

National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB) (2008) Insurance fraud fact sheet, National Insurance Crime Bureau, http://nicb.org/theft_and_fraud_awareness/fact_sheets, accessed 3 November 2015.

O’Fallon, M.J. and Butterfield, K.D. (2005) A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 1996–2003. Journal of Business Ethics 59 (4): 375–413.

Papon, T. (2008) The effect of pre-commitment and past experience on insurance choices: An experimental study. The Geneva Risk and Insurance Review 33 (1): 47–73.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) (2005) Consideration of fraud in a financial statement audit. AU Section 316, http://www.pcaobus.org, accessed April 2014.

Rest, J. (1986) DIT Manual: Manual for the Defining Issues Test. Third Edition. Center for the study of Ethical Development: University of Minnesota.

Reynolds, S.J. (2006) Moral awareness and ethical predispositions: Investigating the role of individual differences in the recognition of moral issues. Journal of Applied Psychology 91 (1): 233–243.

Schiller, J. (2006) The impact of insurance fraud detection systems. Journal of Risk and Insurance 73 (3): 421–438.

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S.J. and Kraft, K.L. (1996) Moral intensity and ethical decision-making of marketing professionals. Journal of Business Research 36 (3): 245–255.

Tennyson, S. (1997) Economic institutions and individual ethics: A study of consumer attitudes toward insurance fraud. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 32 (2): 247–265.

Tennyson, S. and Salsas-Forn, P. (2002) Claims auditing in automobile insurance: Fraud detection and deterrence objectives. Journal of Risk and Insurance 69 (3): 289–308.

Trevino, L.K. (1986) Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review 11 (3): 601–617.

Tseng, L.-M. and Su, W.-P. (2013) Customer orientation, social consensus and insurance salespeople’s tolerance of customer insurance frauds. International Journal of Bank Marketing 31 (1): 38–55.

VanMeter, R.A., Grisaffe, D.B., Chonko, L.B. and Roberts, J.A. (2013) Generatio Y’s ethical ideology and its potential workplace implications. Journal of Business Ethics 117 (1): 93–109.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Katie School of Insurance & Financial Services at Illinois State University for financial support provided for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

1(PhD, Virginia Tech) is Associate Professor of Marketing at Illinois State University. Her primary research interests focus on the development and management of Business-to-Business (B-to-B) relationships and interdisciplinary research such as business ethics. Her research has been published in Journal of Service Research, Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, Journal of Marketing Channels, among many others, as well as a chapter in recently published Handbook of Service Marketing Research.

Appendices

Appendix A

Scenario descriptions and samples

Scenario 1: Small, local insurer, $750 fraud amount (padding) to cover the friend’s loss.

Scenario 2: Small, local insurer, $750 fraud amount (padding) to cover the deductible required.

Scenario 3: Large, online insurer, $750 fraud amount (padding) to cover the friend’s loss.

Scenario 4: Large, online insurer, $750 fraud amount (padding) to cover the deductible required.

Scenario 1 for the Millennials

Mickey is a college student just like you. Mickey is renting an apartment, and he has renter’s insurance that provides protection if his personal property is damaged, stolen or destroyed. He purchased the insurance from a personal agent at a small, local credit union with about 1000 members.

One day, his upstairs neighbors have a kitchen fire, and the water used to put out the fire by the fire department ruins everything in an apartment he shares with a close friend. Unfortunately, his friend’s computer is ruined by the water, and he does not have the money to buy a new computer mid-semester. The roommate does not have renter’s insurance to cover the loss of the computer. The roommate asks Mickey to submit a claim for his computer along with Mickey’s claim. Mickey knows that this goes against the insurance contract, and understands that fabricating damage claims can subsequently raise cost of insurance premiums for other credit union members.

Mickey goes ahead and submits the claim for the roommate’s computer (value estimated at $750).

Scenario 1 for the adults

Mickey is a homeowner, and his homeowner’s insurance is provided by a small, local credit union with about 1000 members.

One day, a strong storm blew the shingles off of Mickey’s house. His friend was visiting at the time and his car was parked in the driveway. His car’s windshield was cracked, though not from the storm. His friend had recently lost his job and he was unable to afford the repair cost. His friend asks Mickey to submit a claim for his car windshield along with Mickey’s claim. Mickey knows that this goes against the insurance contract, and understands that fabricating damage claims can subsequently raise cost of insurance premiums for other credit union members.

Mickey goes ahead and submits the claim for his friend’s windshield (value estimated at $750).

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ishida, C., Chang, W. & Taylor, S. Moral intensity, moral awareness and ethical predispositions: The case of insurance fraud. J Financ Serv Mark 21, 4–18 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/fsm.2015.26

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/fsm.2015.26