Abstract

It is an accepted truth that parties are the central political actors in all liberal democracies. This dominance of parties is often considered the logical outcome of rational politicians’ attempts to maximize their utility in terms of votes and policy influence. However, the last 20 years have seen a number of significant Independent (that is, non-party) actors emerge in more than a few political systems. From an actor-centred point of view, party affiliation can, depending on the particular environment, be rather a liability than an advantage, which has significant implications for the role of non-party actors in face of weakening party democracies. To show this point, we deliver an account of the rise of Independents in the Irish political system, opposed to the dominant scholarly perspective that tends to consider Independents as an idiosyncrasy. We show that the choice of organizational independence over party affiliation represents a reaction to incentives inherent in the electoral, parliamentary and governmental stages that can disfavour party as the most efficient vehicle for individual goal attainment. This becomes evident when avoiding the misleading comparison between parties as collective bodies with that of Independents as individuals, instead focusing on the respective strategic positions of the individual MPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout this paper the term ‘Independent’ and its concomitant categories are capitalized when referring to Independent politicians. This is done to distinguish between the use of the word ‘independent’ as a general adjective and as a noun signifying a particular political status.

Provided of course that non-party candidacies (not just personalized party lists) are permitted, which is predominantly the case in countries using candidate-centred electoral systems, examples being single-member plurality (SMP), proportional representation by the single transferable vote (PR-STV), the double-ballot, and the alternative vote.

This is the same definition used by Chubb (1957, 132) and Marsh et al. (2008, p. 49).

This would explain why candidates running for election in the US campaign on a party label (where it is a valued asset), but when elected act far more independently in office.

The main difference being that the formation of a government, which usually acts as an incentive to strategic voting, does not arise at second-order elections.

Many candidates do not contest local elections simply to sit on the council; for some it is a stepping stone to holding a national office. Because local councils do not have much authority, there are few direct incentives for those who wish to wield power and shape policy; however there are indirect incentives for such individuals if they see local elections as a necessary hurdle to clear before contesting national elections.

This reflected the traditional cyclical performance of Independents, and was also a product of (a) the inability of the raft of Independents elected in 2002 to deliver ‘pork’ for their respective constituencies and (b) the emergence of a credible alternative government in 2007 (see Gallagher, 2007, p. 92).

In this, and in all future uses of the term, ‘important’, unless otherwise stated, refers to scores of seven or greater on the scale of importance.

Although such a small difference is not significant at a P<0.05 level, the very fact that it is approximately equal to the proportion of party candidates is a practically significant result.

Malta is the only other country outside Ireland using PR-STV to elect its lower house of parliament.

Indeed, neither party labels nor symbols were included on the ballot sheet in Ireland until 1963.

Forty-five per cent of the 45 party TDs who ran Independent at a succeeding election retained their seat (from 1923 to 2002), quite a considerable level of success (Weeks, 2008a).

‘Bailiwick’ refers to a localized portion of a constituency that a candidate is restricted to campaigning in by his/her party, usually done to ensure an even spread of votes among the party's candidates to maximize their seat return.

There is no restriction on any individual declaring the formation of a party. However, to form a party that is officially recognized by the authorities, there is a number of criteria to meet. The organization must have either one TD or three local representatives; three hundred paid-up members; a party constitution; and the organization must hold an annual general meeting (Source: various Electoral Acts; available at www.irishstatutebook.ie).

Interview with Independent TD Michael Lowry on ‘The Constituency’, RTÉ Radio 1, 16 December 2006.

Only six of the 16 Independent TDs who have joined established political parties within parliament since the 1920s have held their seat as a party TD at the succeeding election. This explains why only three Independents crossed over to the party benches in the Dáil between 1961 and 2005 (Weeks, 2008a).

From a large party's point of view (such as Fianna Fáil), it is more beneficial to gather the support of Independents, rather than of a small party, as the former do not occupy government ministries and, moreover, usually have less weight than a small party and therefore are likely to demand fewer policy concessions.

Ranging from the extreme north-west (Donegal) to the south-west (Kerry) and to the east coast (Wicklow).

Evidence of this was seen in November 2001, when an Independent TD refused to bow to government pressure to apologize for his claims that the Minister for Justice in the 1994–1997 government should be investigated for an abuse of power (The Irish Times, 27 November 2001).

It has already been the subject of a workshop at the Joint Sessions of the European Consortium of Political Research in 2006.

The calculus states that rational individuals should only run when pB>C (where p is the probability of victory, B is the benefits gained from running, and C is the costs of running).

References

Aldrich, J. (1995) Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Political Parties in America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Anckar, D. (2000) Party systems and voter alignments in small island states. In: L. Karvonen and S. Kuhnle (eds.) Party Systems and Voter Alignments Revisited. London: Routledge, pp. 261–283.

Andeweg, R.B. (2003) Beyond representativeness? Trends in political representation. European Review 11 (2): 147–161.

van Biezen, I. (2003) Political Parties in New Democracies: Party Organization in Southern and East-Central Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Black, G. (1972) A theory of political ambition: Career choices and structural incentives. American Political Science Review 66 (1): 144–159.

Bolleyer, N. (2004) Kleine Parteien zwischen Stimmenmaximierung, Politikgestaltung und Regierungsübernahme am Beispiel Irlands und Dänemarks. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 1: 132–148.

Bolleyer, N. (2007) Small parties – from policy pledges to government policy. West European Politics 30 (1): 121–147.

Bolleyer, N. (forthcoming) Inside the cartel party: Party organisation in government and opposition Please provide volume and page ranges in the reference Bolleyer (forhcoming). Political Studies.

Bowler, S. (2000) Parties in legislature: Two competing explanations. In R.J. Dalton and M.P. Wattenberg (eds.) Parties without Partisans, Political Change in Advanced Industrial Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 157–179.

Cain, B., Ferejohn, J. and Fiorina, M. (1987) The Personal Vote. Constituency Service and Electoral Independence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carey, J.M. and Shugart, M.S. (1995) Incentives to cultivate a personal vote: A rank ordering of electoral formulas. Electoral Studies 14 (4): 417–439.

Carty, R.K. (1981) Electoral Politics in Ireland: Party and Parish Pump. Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Chubb, B. (1957) The independent member in Ireland. Political Studies V, pp. 131–141.

Collet, C. (1999) Can they be serious? The rise of minor parties and independent candidates in the 1990s. PhD dissertation University of California, Irvine, USA.

Costar, B. and Curtin, J. (2004) Rebels with a Cause: Independents in Australian Politics. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Cox, G.W. and Mc Cubbins, M.G. (1993) Legislative Leviathan: Party Government in the House. California: California University Press.

Dalton, R.J. and Weldon, S.A. (2005) Public images of parties: A necessary evil? West European Politics 28 (5): 931–951.

Denver, D. and Hands, G. (1997) Modern Constituency Electioneering: Local Campaigning in the 1992 General Election. London: Frank Cass.

Fleming, S. et al, (2003) The candidates’ perspective. In: M. Gallagher, M. Marsh and P. Mitchell (eds.) How Ireland Voted 2002. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 57–88.

Gallagher, M. (1976) Electoral Support for Irish Political Parties 1927–1973. London: Sage.

Gallagher, M. (2007) The earthquake that never happened: Analysis of the results. In: M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (eds.) How Ireland Voted 2007. London: Palgrave, pp. 78–105.

Garry, J., Kennedy, F., Marsh, M. and Sinnott, R. (2003) What decided the election? In M. Gallagher, M. Marsh and P. Mitchell (eds.) How Ireland Voted 2002. London: Palgrave, pp. 119–143.

Gilland, K. (2003) Irish party competition in the new millenium. Irish Political Studies 18: 40–59.

Hale, H.E. (2005) Why not Parties in Russia? Democracy, Federalism, and the State. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Joyce, J. and Murtagh, P. (1983) The Boss: Charles J. Haughey in Government. Dublin: Poolbeg Press.

Katz, R. (1980) A Theory of Parties and Electoral Systems. Baltimore, MD and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Katz, R. and Mair, P. (1995) Changing models of party organization and party democracy: The emergence of the cartel party. Party Politics 1 (1): 5–28.

Katz, R. and Mair, P. (2008) MPs and parliamentary parties in the age of the cartel party. presented in the Workshop ‘Parliamentary and Representatives Roles in Modern Legislatures’ at the ECPR Joint Sessions in Rennes, 11–16 April 2008.

Key, V.O. (1966) The Responsible Electorate, Rationality in Presidential Voting, 1936–1960. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard UP.

Laver, M. and Shepsle, K.A. (1999) How political parties emerged from the primeval slime: Party cohesion, party discipline, and the formation of governments. In: S. Bowler, D.M. Farrell and R. Katz (eds.) Party Discipline and Parliamentary Government. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, pp. 23–48.

Mair, P. (1987) The Changing Irish Party System. London: Pinter.

Mair, P. (1994) Party organizations: From civil society to the state. In: R. Katz and P. Mair (eds.) How Parties Organize, Change and Adaptation in Party Organizations in Western Democracies. London: Sage, pp. 1–22.

Mair, P. (1997) Party System Change: Approaches and Interpretations. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mair, P. (1998) Representation and participation in the changing world of party politics. European Review 6 (2): 161–174.

Mair, P. (2005) Democracy Beyond Parties. Irvine: Center for the Study of Democracy, University of California.

Mair, P. and Weeks, L. (2005) The Party System. In J. Coakley and M. Gallagher (eds.) Politics in the Republic of Ireland, 4th edn. London: Routledge, pp. 135–160.

Maor, M. (1998) Parties, Conflicts and Coalitions in Western Europe, Organizational Determinants of Coalition Bargaining. London: Routledge.

Marsh, M. (2007) Candidates or parties? Objects of electoral choice. Party Politics 13 (4): 500–527.

Marsh, M., Sinnott, R., Garry, J. and Kennedy, F. (2008) The Irish Voter. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Mershon, C. and Shvetsova, O. (2007) Parliamentary cycles and party switching in legislatures. Comparative Political Studies 20 (10): 1–29.

Moser, R.G. (1989) Independents and party formation: Elite partisanship as an intervening variable in Russian politics. Comparative Politics 36 (2): 147–163.

Owen, D. and Dennis, J. (1996) Anti-partyism in the USA and support for Ross Perot. European Journal of Political Research 29 (3): 383–401.

Panebianco, A. (1988) Political Parties: Organizations and Power. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Pedersen, M. (1982) Towards a new typology of party lifespans and minor parties. Scandinavian Political Studies 5 (1): 1–16.

Reed, S.R. (2003) Nominees and Independents in Japan's Liberal Democratic Party: A Case of Functional Irrationality. Chuo University, Typescript, Tokyo.

Schattschneider, E.E. (1977) Party Government. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Schlesinger, J.A. (1966) Ambition and Politics: Political Careers in the United States. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Sharman, C. (2002) Politics at the margin: Independents and the Australian political system. Presented at the Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House, Sydney, Australia, 17 May.

Sinnott, R. (1995) Irish Voters Decide. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Strøm, K. (1990) Minority Government and Majority Rule. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Wattenberg, M.P. (1991) The Rise of Candidate-Centred Politics: Presidential Elections of the 1980s. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weeks, L. (2003) The Irish parliamentary election, 2002. Representation 39 (3): 215–226.

Weeks, L. (2007a) Does PR-STV help independents? presented at the Annual Conference of the Political Studies Association of Ireland, Dublin, 17–19 October 2007.

Weeks, L. (2007b) Candidate selection: Democratic centralism or managed democracy? In: M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (eds.) How Ireland Voted 2007. London: Palgrave, pp. 48–65.

Weeks, L. (2008a) We don’t like (to) party. Explaining the significance of independents in Irish political life. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Trinity College, University of Dublin.

Weeks, L. (2008b) Independents in government. A Sui generis model. In: K. Deschouwer (ed.) Newly Governing Parties. London: Routledge, pp. 136–156.

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Mair and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

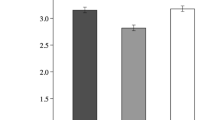

To determine why Independents decide to run, a survey of Independent and party candidates was conducted immediately after the 2004 local elections (see Weeks, 2008a). Methodologically speaking, the survey is advantageous to older studies in several respects. Rather than replicating Denver and Hand's methods of surveying election agents (1997), Weeks surveyed the candidates themselves. This was largely because the focus of his study was Independent candidates, who tend not to have a full-time election agent, especially at local elections, and it is usually just the candidates themselves who have the best knowledge of their campaign details. A four-page questionnaire with 35 questions was sent by post to each of the 297 Independent candidates and to 556 of the 1,665 party candidates. Independents received a slightly different version that had an extra five questions pertaining specifically to their Independent status. As there can be a difference in behaviour between urban and rural candidates, 353 surveys were sent to party candidates for county councils, and 203 for those running in city councils. Ensuring the inclusion of a reasonable number of both city and county candidates was necessary for the controlling of particular effects that might be unique to a particular locale.

The quantity to survey from each party was based on their number of candidates as a proportion of total candidacies in city and county councils. This was done to ensure a reasonable weighting of responses so that one party would be not overly represented in the final data set. The party respondents were chosen at random from a list of their party's candidates within the two separate forms of councils. Details of the numbers of questionnaires sent and returned according to party affiliation are detailed in Table A1.

The questionnaire was posted 1 week after the elections, and was followed up by a reminder postcard 3 weeks later to those who had not yet returned it. Two weeks later, the questionnaire was re-sent to all respondents yet to reply. This labour-intensive procedure produced a very satisfactory final response rate of 59 per cent, which exceeds that achieved by Denver and Hands (1997) (53 per cent) and Gilland (2003) (47 per cent) in similar studies. The response rate is of particular importance when making inferences from surveys. A low response rate means that there is an increased probability of the sample data being not randomly selected; that is, those who did respond may not be reflective of the random sample originally drawn. Consequently, the random sampling error can increase, resulting in unreliable findings. Such biases are less likely to occur in a candidate survey because of the low levels of heterogeneity among same party candidates (as opposed to voters), reducing the variance in the sample. In any case, the reasonable response rates means that unreliable findings are less likely to occur, especially considering the rates being larger to other candidate surveys. Replicating the methodology of Denver and Hands (1997, pp. 322–323), the representativeness of the responses can be checked against a few variables, notably party vote and turnout. As Table A2 indicates, the figures for the constituencies with respondents are quite similar to the national mean, which indicates that the campaigns covered by the sample survey are very representative of all campaigns.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bolleyer, N., Weeks, L. The puzzle of non-party actors in party democracy: Independents in Ireland. Comp Eur Polit 7, 299–324 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2008.21

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2008.21