Abstract

This study examines why Americans have positive or negative affect towards the US federal government. Specifically, it draws on existing theoretical and empirical research regarding individual attitudes towards the European Union, examining the effect of ethnocentrism on American attitudes towards the federal government. Relying on this existing research regarding the EU, it is hypothesized that those who are more ethnocentric will be more negative towards the US federal government. To test this expectation, we use longitudinal data from the American National Election Study from 1992 to 2012. We find those who are more ethnocentric are significantly more likely to possess negative attitudes towards the federal government. These findings have important implications for policymaking at both the federal and state levels, as well as party positioning both at the time of and between American elections, and the overall stability of multilevel governance in the United States. Additionally, the findings of this study indicate that theories designed to explain phenomena in the European Union are applicable to the US case.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A second major theoretical approach from the EU literature focuses on utilitarian appraisals or economic calculations (see Gabel 1998; Hooghe and Marks 2004; 2005). This approach argues that European integration has led to economic benefits for some, but not all, people, and those who have benefited will be more supportive of the EU. Due to the different political and economic structures in place in the US compared to the EU, there is less applicability of the utilitarian appraisals theoretical approach to the US case. That is to say, very few people in the United States give thought to the possibility of restrictions on interstate trade within the borders of the United States. Rather, the ability to trade and move between states, and the single currency of the United States are so ingrained in the American psyche, one would not expect those who gain monetarily from these policies to be any more or less supportive of the federal government. However, as the utilitarian appraisal theoretical approach is important in the research on the European Union, we included measures of sociotropic economic evaluations, education level, and household income (see Gabel 1998; McLaren 2002) in our models.

Importantly, this understanding is not of mere academic concern. In fact, research suggests that the vote in favor of “Brexit” was, in large part, driven by fear of immigration being made easier by the UK’s membership of the EU, and the perceived threat immigrants pose to what it means to be British (Clarke et al. 2017; Goodwin and Milazzo 2017). Europe began experimenting with integration and multilevel governance in earnest in only the mid-twentieth century, when the Treaty of Rome founded the European Economic Community (the predecessor of the current European Union). Because of this particular context in Europe, the identity-based theory explaining attitudes towards the EU discussed above (see McLaren 2002; Carey 2002) focuses on identification with a particular nation-state (e.g., France, Germany, the Netherlands, etc.).

While the above theory developed in the EU is applicable to the case of the US, an important distinction should be made. In the European Union, there is a small (about 10% of the European population over time; see Williams and Bevan 2019), but real group of hard Eurosceptics that oppose the existence of the European Union (see Taggart and Szczerbiak (2004) for a discussion of hard Euroscepticism). The percentage of the population that believes the US federal government should not exist is smaller, but not non-existent. For example, in April 2016, a handful of county Republican parties in Texas voted in favor of a resolution calling for Texas independence from the United States to be voted on at the state Republican convention, coming within 2 votes of adding a call for secession to the Texas Republican platform (Fetterman 2017). In June 2016, a hashtag calling for a “Texit,” or Texas exit from the US, began appearing on social media (Dart 2016). Additionally, a burgeoning “California secession” movement has grown, particularly after the 2016 Presidential election, with supporters attempting to force a statewide referendum on California leaving the United States. It should also be noted, most people in Europe who espouse Eurosceptic attitudes tend towards soft Euroscepticism (see van Elsas and van der Brug (2015) for a discussion of soft and hard Euroscepticism in the public). Soft Eurosceptics are often understood as being opposed to the policies of the European Union, but not the idea of Europe in general. This fits with what is seen in the United States, where questioning the right of the federal government to exist is less common, and opposition to the policies of the federal government is quite common.

It should be noted, there is a difference between the EU and the US in that in the EU, the “others” are other countries (or the people of other countries), and therefore explicitly part of the EU. In the United States, the “others” are people of different races. While people of different races are represented by the US federal government, the geopolitical cleavage in society is the state, not the racial group. That is, senators in the US are not elected from the “other” groups, whereas, in the EU, representatives in the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers do represent the “other” groups. This means that those opposed to the “others” in the EU are concerned about the entirety of European governance degrading one’s national culture. Whereas those opposed to the “others” in the US are not necessarily opposed to the existence of the federal government degrading one’s racial identity. Rather they are concerned about federal-level policies degrading one’s racial identity. While this is an important differentiation, it should not greatly affect the expectations of this study. Within the literature on opposition to the EU, the furthering of integration and the furthering of European policy are understood to be, if not the same, extremely similar (see Franklin and Wlezien 1997; Toshkov 2011; Williams 2016). Thus, the distinction between the EU and the US on the role of the “others” in government becomes blurred. Additionally, this differentiation between the EU and the US should not alter the expectations of this study, as opposition to the existence of EU power, and opposition to US federal policy should both manifest themselves in negative affect towards the EU and the US federal government, respectively.

While it is possible that state and local governments might enact similar policies to those enacted by the federal government, historically, this has not been the case. In fact, movements, such as the “Patriots” and numerous “militias,” which have argued for abolition of the federal government, are also virulently racist (see Abanes 1996; Dees 1996; Crawford and Burghart 1997; van Dyke and Soule 2002). The history of the United States is one in which states enacted policies designed to disenfranchise and marginalize certain groups (e.g., Jim Crow). Thus, it is possible that states and local governments create policies that require individuals to accept the norms and culture of out-groups; however, history suggests that the federal government has played this role more often than state and local governments. Thus, one would expect individuals who do not want to accept the norms and culture of out-groups to develop negative affect towards the federal government. If states were historically the level of governance that pushed for racial integration, one might expect to see negative affect towards state government among those who are more ethnocentric. In essence, within a multilevel system, one would expect to see negative affect towards the level of government that is most threatening to an individual’s identity. However, as states are more homogenous, they are better suited to represent majority interests.

The opposite of this hypothesis would also be expected.

1996 is not included as the survey instruments necessary to measure certain variables are not available.

The text of the feeling thermometer question is “We'd also like to get your feelings about some groups in American society. When I read the name of a group, we'd like you to rate it with what we call a feeling thermometer. Ratings between 50 degrees-100 degrees mean that you feel favorably and warm toward the group; ratings between 0 and 50 degrees mean that you don't feel favorably towards the group and that you don't care too much for that group. If you don't feel particularly warm or cold toward a group you would rate them at 50 degrees. If we come to a group you don't know much about, just tell me and we'll move on to the next one…still using the thermometer, how would you rate the federal government in Washington.”.

For descriptive statistics for all variables in this study in all models, see Table 3 in the appendix.

Kinder and Kam (2009) utilize a similar measure of ethnocentrism operationalized through feelings thermometers.

Factor analysis was conducted for the feeling thermometers for each racial grouping, white, black, Hispanic, and Asian-American. The feeling thermometer for each group was factored with the inverted thermometers for out-groups. For whites, the thermometers factored together with absolute values of 0.59 or higher. For blacks, the thermometers factored together with absolute values of 0.53 or higher. For Hispanics and Asian-Americans, the thermometers factored together with absolute values of 0.65 or higher. Further, reliability tests show Cronbach’s alpha scores over 0.80 for all groupings. This suggests that these measures can be used as an additive index.

It should be noted, as a robustness check, tests were conducted in which the independent variable was simply an individual’s combined inverted feeling thermometer scores (i.e., only negativity towards out-groups). These results were virtually identical to the results of the main test of this study (see Table 4 of the appendix).

If an interaction between ethnocentrism and an individual’s identification as white were included in the model, the range for this variable in the dataset would be 0 to 397 with a mean of 124.753 and a standard deviation of 92.713. Importantly, this indicates that whites are far more likely to be ethnocentric than non-whites.

As a robustness test, we included an objective measure of economic output, GDP per capita, in our main models along with the sociotropic measure of economic performance. The results of these tests do not change the effects of the main independent variable in any substantive way. We choose to not include GDP per capita in our main models as doing so precludes the inclusion of year dummy variables, which are preferable as they control for any idiosyncratic factors that occurred in a given year (including economic factors), while controlling for GDP per capita does not.

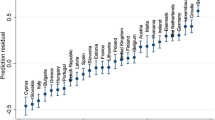

In order to examine the possibility of cross-time variation in our models, we ran a series of robustness checks in which ethnocentrism was interacted with the year dummy variables. The results show that ethnocentrism still maintains the strong negative effect seen in the main models of this study. However, there are definitive cross-time differences in effect as well. Specifically, we see that the negative effect of ethnocentrism on positivity towards the federal government in 2008 is greater than in 2012. Further, we examined the conditioning effect of who was in the office of the President at a particular time on the relationship between ethnocentrism and the different measures of affect towards the federal government. This was done by interacting a dummy variable indicating who was in office at a time with the measure of ethnocentrism. Across 16 tests, only 3 tests (when affect towards the federal government is measured as positivity on a scale of 0–100 during the George W. Bush and Obama presidencies, and when affect towards the federal government is measured as perception of corruption during the Obama presidency) show a statistically significant relationship between ethnocentrism conditioned on Presidential administration, and affect towards the federal government. Importantly, the interaction between a dummy variable for George W. Bush and ethnocentrism shows a negative coefficient, suggesting that those who are more ethnocentric during the George W. Bush presidency were more likely to have a negative view of the federal government. The interaction between a dummy variable for Obama and ethnocentrism shows a positive coefficient when affect was measured as the degree of positivity (0–100) and a negative coefficient when affect was measured as perception of corruption. This suggests that those who were more ethnocentric during the Obama presidency were more positive towards the federal government and less likely to perceive corruption. These findings should not be interpreted as definitive as these findings lack robustness; however, they may be suggestive of an elite discourse effect, as Republican elites are more likely to emphasize a need for less federal power.

Additionally, robustness tests in which a measure of interpersonal trust was included were run. The measure of interpersonal trust has no effect on attitudes towards the federal government. We do not include this variable in our main models as it does not exist for 2012.

The chi-squared obtained through the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test is 2.83 with a p-value of 0.093. While this is marginally significant, using White’s robust standard errors produces a more conservative estimate of statistical significance.

While factor analysis suggests the three additional measures load fairly well together, with factor loadings all above 0.48, the measures are examined separately in order to provide a more nuanced understanding of the effect of ethnocentrism on attitudes towards the federal government.

The predicted probabilities are only reported for values for trust in the federal government of 1 (trusting the government most of the time) and 2 (trusting the government some of the time). Predicted probabilities aren’t reported for values of 0 (trusting the government all of the time) and 4 (trusting the government none of the time), because there is little change in these predicted probabilities as ethnocentrism varies.

The predicted probabilities are only reported for values of 1 (belief that the federal government wastes some tax money) and 2 (belief that the federal government wastes a lot money). Predicted probabilities are not report for values of 0 (belief that the federal government does not waste much tax money) because there is little change in these predicted probabilities as ethnocentrism varies.

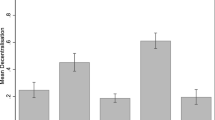

It is possible that there are differences in the effect among groups based on who holds the office of the President. To examine this possibility, we ran a series of robustness checks in which Model 5 was run, but the time period was restricted by who was President (i.e., George H.W. Bush, Clinton, George W. Bush, or Obama). Overall, the results are quite similar. The effect of ethnocentrism, however, appears to be greater among Hispanic-Americans during the George H.W. Bush presidency, and among blacks during the Clinton presidency. There are no instances in which the effect of ethnocentrism on affect towards the federal government is lower for a particular group. It should be noted, during the George H.W. Bush and the Obama presidencies there is evidence that Asian-Americans who are more ethnocentric are also more negative towards the federal government, but these findings are based on only 27 individuals during the George H.W. Bush presidency, and 92 individuals during the Obama presidency, and therefore, should be interpreted with caution.

References

Abanes, R. 1996. American Militias: Rebellion, Racism, and Religion. Downers Grover, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Adams, J., M. Clark, L. Ezrow, and G. Glasgow. 2004. Understanding Change and Stability in Party Ideologies: Do Parties Respond to Public Opinion or to Past Election Results? British Journal of Political Science 34 (4): 589–610.

Adams, J., M. Clark, L. Ezrow, and G. Glasgow. 2006. Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different than Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties’ Policy Shifts, 1976–1998. American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 513–529.

Anderson, C.J. 1998. When in Doubt, Use Proxies. Comparative Political Studies 31 (5): 569–601.

Anthias, F., and N. Yuval-Davis. 1983. Contextualizing Feminism: Gender, Ethnic and Class Divisions. Feminist Review 15: 62–75.

Bakvis, H., and D. Brown. 2010. Policy Coordination in Federal Systems: Comparing Intergovernmental Processes and Outcomes in Canada and the United States. Publius The Journal of Federalism 40 (3): 484–507.

Banks, A. 2014. The Public’s Anger: White Racial Attitudes and Opinions Toward Health Care Reform. Political Behavior 36 (3): 493–514.

Banks, A., and N. Valentino. 2012. Emotional Substrates of White Racial Attitudes. American Journal of Political Science 56 (2): 286–297.

Benefield, C., and C.J. Williams. 2019. Taking Official Positions: How Public Policy Preferences Influence the Platforms of Parties in the United States. Electoral Studies 57: 71–78.

Bianco, W. 1994. Trust: Representatives and constituents. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bobo, L., and V. Hutchings. 1996. Perceptions of Racial Group Competition: Extending Blumer’s Theory of Group Position to a Multiracial Social Context. American Sociological Review 61 (6): 951–972.

Branscombe, N., M. Schmitt, and K. Schiffhauer. 2007. Racial Attitudes in Response to Thoughts of White Privilege. European Journal of Social Psychology 37 (2): 203–2015.

Carey, S. 2002. Undivided Loyalties: Is National Identity an Obstacle to European Integration? European Union Politics 3 (4): 387–413.

Chanley, V., T.J. Rudolph, and W. Rahn. 2000. The Origins and Consequences of Public Trust in Government: A Time Series Analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly 64 (3): 239–256.

Cheneval, F., S. Lavenex, and F. Schimmelfennig. 2014. Demoi-cracy in the European Union: Principles, Institutions, Policies. Journal of European Public Policy 22 (1): 1–18.

Citrin, J. 1974. Comment: The Political Relevance of Trust in Government. American Political Science Review 68: 973–988.

Citrin, J., B. Reingold, and D. Green. 1990. American Identity and the Politics of Ethnic Change. Journal of Politics 52 (4): 1124–1154.

Citrin, J., C. Wong, and B. Duff. 2001. The Meaning of American National Identity: Patterns of Ethnic Conflict and Consensus. In Social Identity, Intergroup Conflict, and Conflict Reduction, ed. R. Ashmore, L. Jussim, and D. Wilder. Oxford: Oxford University Press.3

Clarke, H., M. Goodwin, and P. Whiteley. 2017. Why Britain Voted for Brexit: An Individual-Level Analysis of the 2016 Referendum Vote. Parliamentary Affairs 70 (3): 439–464.

Craig, M., and J. Richeson. 2014a. On the Precipice of a ‘Majority-Minority’ America: Perceived Status Threat from the Racial Demographic Shift Affects White Americans’ Political Ideology. Psychological Science 25 (6): 1189–1197.

Craig, M., and J. Richeson. 2014b. More Diverse Yet Less Tolerant?” How the Increasingly Diverse Racial Landscape Affects White Americans’ Racial Attitudes. Personal and Social Psychology Bulletin 40 (6): 750–761.

Crawford, R., and D. Burghart. 1997. Guns and Gavels: Common Law Courts, Militias and White Supremacy. In The Second Revolution: States Rights, Sovereignty, and Power of the country, ed. Eric Ward. Seattle: Peanut Butter Publishing.

Danbold, F., and Y. Huo. 2014. No Longer ‘All-American’? Whites’ Defensive Reactions to Their Numerical Decline. Social Psychological and Personality Science 6: 210–218.

Dart, T. 2016. ‘Why not Texit? Texas Nationalists Look to Brexit Vote for Inspiration. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jun/19/texas-secession-movement-brexit-eu-referendum. Accessed 25 Feb 2020.

Dees, M. 1996. Gathering Storm: America’s Militia Threat. New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

De Vries, C., and I. Hoffmann. 2015. What Do the People Want? Opinions, Moods and Preferences of European Citizens. Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Enos, R. 2014. Causal effect of intergroup contact on exclusionary attitudes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United State of America 111 (10): 3699–3704.

Erikson, R.S., M.B. MacKuen, and J.A. Stimson. 2002. Public Opinion and Policy: Causal Flow in a Macro System Model. In Jeff Manza, Fay Lomax Cook, and Benjamin I. Page (eds.), Navigating Public Opinion: Polls, Policy, and the Future of American Democracy.

Ezrow, L., C.E. de Vries, M.R. Steenbergen, and E.E. Edwards. 2011. Mean Voter Representation and Partisan Constituency Representation: Do Parties Respond to the Mean Voter Position or To Their Supporters? Party Politics 17 (3): 275–301.

Franklin, M., M. Marsh, and L. McLaren. 1994. Uncorking the Bottle: Popular Opposition to European Unification in the Wake of Maastricht. Journal of Common Market Studies 32 (4): 455–472.

Franklin, M., and C. Wlezien. 1997. The Responsive Public: Issue Salience, Policy Change, and Preferences for European Unification. Journal of Theoretical Politics 9 (3): 347–363.

Franklin, M., C. van der Eijk, and M. March. 1995. Referendum Outcomes and Trust in Government: Public Support for Europe in the wake of Maastricht. West European Politics 18 (3): 101–117.

Fetterman, M. 2017. Despite Secession Talk, Breaking Up is Hard to Do.” Stateline. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2017/05/04/despite-secession-talk-breaking-up-is-hard-to-do. Accessed 12 Nov 2017.

Fredrickson, G.M. 2003. The Historical Construction of Race and Citizenship in the United States. United National Research Institute for Social Development.

Gabel, M.J. 1998. Public Opinion and European Integration: An Empirical Test of Five Theories. Journal of Politics 60 (2): 333–354.

Gabel, M., and H.D. Palmer. 1995. Understanding Variation in Public Support for European Integration. European Journal of Political Research 27 (1): 3–19.

Gallup. 2019. “Trust in Government.” https://news.gallup.com/poll/5392/trust-government.aspx. Accessed 20 Jan 2020.

Gilens, M. 1996. ‘Race Coding’ and White Opposition to Welfare. American Political Science Review 90 (3): 593–604.

Gilens, M. 1999. Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goodwin, M., and C. Milazzo. 2017. Taking Back Control? Investigating the Role of Immigration in the 2016 Vote for Brexit. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117710799.

Hetherington, M. 1998. The Political Relevance of Political Trust. American Political Science Review 92: 791–808.

Hetherington, M., and S. Globetti. 2002. Political Trust and Policy Preferences. American Journal of Political Science 46 (2): 253–275.

Hetherington, M., and J. Husser. 2012. How Trust Matters; The Changing Political Relevance of Political Trust. American Journal of Political Science 56 (2): 312–325.

Hetherington, M., and J. Nugent. 2001. Explaining Public Support for Devolution: The role of political trust. In What is it about Government that Americans Dislike?, ed. J. Hibbing and E. Theiss-Morse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hobolt, S.B., and C.E. de Vries. 2016. Public Support for European Integration. Annual Review of Political Science 19: 413–432.

Hofstadter, R. 1965. The Paranoid Style in American Politics. New York: Vintage Books.

Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2004. Does Identity or Economic Rationality Drive Public Opinion on European Integration. PS: Political Science & Politics 37 (3): 415–420.

Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2005. Calculation, Community, and Cues: Public Opinion on European Integration. European Union Politics 6 (4): 419–443.

Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2009. A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. British Journal of Political Science. 39 (1): 1–23.

Huddy, L. 2013. From Group Identity to Political Cohesion and Commitment. In Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, ed. L. Huddy, D. Sears, and J. Levy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hurwitz, J., and M. Peffley. 2005. Playing the Race Card in the Post-Willie Horton Era: The Impact of Racialized Code Words on Support for Punitive Crime Policy. Public Opinion Quarterly 69: 99–112.

Iyengar, S., Y. Lelkes, M. Levendusky, N. Malhotra, and S.J. Westwood. 2019. The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science 22: 129–146.

Jardina, A. 2019. White Identity Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jones. J.M. 2020. “Trump Approval Steady at 49%.” Gallup.https://news.gallup.com/poll/286280/trump-job-approval-steady.aspx

Jones, R.P., D. Cox, E.J. Dionne, W.A. Galston, B. Cooper, and R. Lienesch. 2016. How Immigration and Concerns about Cultural Changes are Shaping the 2016 Election: Findings from the 2016 PRI/Brookings Immigration Survey. Washington, DC: Public Religion Research Institute.

Kam, C., and D. Kinder. 2007. Terror and Ethnocentrism: Foundations of American Support for the War on Terrorism. The Journal of Politics 69 (2): 320–338.

Kelemen, R.D. 2015. Lessons from the Europe? What Americans Can Learn from European Public Policies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kinder, D., and C. Kam. 2009. Us Against Them: Ethnocentric Foundations of American Opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kinder, Donald R., and Lynn M. Sanders. 1996. Divided by Color: Racial Politics and Democratic Ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

van Klingeren, M., H.G. Boomgaarden, and C.H. de Vries. 2013. Going Soft or Staying Soft: Have Identity Factors become More Important Than Economic Rationale when Explaining Euroscepticism?”. Journal of European Integration 35 (6): 689–704.

Klüver, H., and J.-J. Spoon. 2014. Who Responds? Voters, Parties, and Issue Attention. British Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123414000313.

Levendusky, M. 2017. Americans, Not Partisans: Can Priming American National Identity Reduce Affective Polarization. Journal of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1086/693987.

Lind, J. 2007. Fractionalization and the Size of Government. Journal of Public Economics 91 (1–2): 51–76.

Luttmer, E. 2001. Group Loyalty and the Taste for Redistribution. Journal of Political Economy 109 (3): 500–528.

Major, B., A. Blodorn, and G. Major Blascovich. 2016. The threat of increasing diversity: Why many White Americans support Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216677304.

Maskovsky, J. 2017. Toward the Anthropology of White Nationalist Postracialism: Comments Inspired by Hall, Goldstein, and Ingram’s ‘The Hands of Donald Trump’. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7 (1): 433–440.

Mason, L. 2016. A Cross-Cutting Calm: How Social Sorting Drive Affective Polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly 80 (1): 351–377.

Mason, L. 2015. I Disrespectfully Agree”: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization. American Journal of Political Science 59 (1): 128–145.

McLaren, L.M. 2002. Public Support for the European Union: Cost/Benefit Analysis or Perceived Cultural Threat? Journal of Politics 64 (2): 551–566.

Mendelberg, T. 1997. “Executing Hortons: Racial Crime in the 1988 Presidential Campaign. Public Opinion Quarterly 61 (1): 134–157.

Miller, A. 1974. Political Issues and Trust in Government: 1964–1970. American Political Science Review 68: 951–972.

Miller, W.E., and D.E. Stokes. 1963. Constituency Influence in Congress. American Political Science Review 57 (1): 45–56.

Oliver, J.E., and J. Wong. 2003. Intergroup Prejudice in Multiethnic Settings. American Journal of Political Science 47 (4): 567–582.

Page, B.I., and R.Y. Shapiro. 1983. Effects of Public Opinion on Policy. American Political Science Review 77 (1): 175–190.

Parker, C.S., and M.A. Barreto. 2013. Change They Can’t Believe In: The Tea Party and Reactionary Politics in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Powell Jr., G.B. 2000. Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Robinson, D.E. 2001. Black Nationalism in American Politics and Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roccas, S., and M. Brewer. 2002. Social Identity Complexity. Personality and SocialPsychology Review 6 (2): 88–106.

Rzepnikowska, A. 2019. Racism and Xenophobia Experienced by Polish Migrants in the UK Before and After Brexit Vote. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (1): 61–77.

Sanchez-Cuenca, I. 2000. The Political Basis of Support for European Integration. European Union Politics 1 (2): 147–171.

Schildkraut, D. 2010. Americanism in the Twenty-First Century: Public Opinion in the Age of Immigration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sears, D., C. van Laar, M. Carrillo, and R. Kosterman. 1997. Is it Really Racist? The Origins of White Americans’ Opposition to Race-Targeted Policies. Public Opinion Quarterly 61: 16–53.

Sears, D., J. Sidanius, and L. Bobo. 2000. Racialized Politics: The Debate about Racism in America. New York: Praeger.

Serricchio, F., M. Tsakatika, and L. Quaglia. 2013. Euroscepticism and the Global Financial Crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies 53 (1): 51–64.

Sides, J., M. Tesler, and L. Vavreck. 2018. Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Silver, N., A. Bycoffe, and D. Mehta. How Popular is Donald Trump? FiveThirtyEight. 28 February 2020. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/trump-approval-ratings/.

Soroka, S.N., and C. Wlezien. 2004. Opinion Representation and Policy Feedback: Canada in Comparative Perspective. Canadian Journal of Political Science 37 (3): 531–559.

Spoon, J.-J., and C.J. Williams. 2017. It Takes Two: How Euroskeptic Public Opinion and Party Divisions Influence Party Positions. West European Politics 40 (4): 741–762.

Stimson, J.A., M.B. MacKuen, and R.S. Erikson. 1995. Dynamic Representation. American Political Science Review 89 (3): 543–565.

Striessnig, E., and W. Lutz. 2016. Demographic Strengthening of European Identity. Population and Development Review 42 (2): 305–311.

Tajfel, H., and J.C. Turner. 1979. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, ed. W.G. Austin and S. Worchel. Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA.

Taggart, P., and A. Szczerbiak. 2004. Contemporary Euroscepticism in the Party Systems of the European Union Candidate States of Central and Eastern Europe. European Journal of Political Research 43 (1): 1–27.

Teed, P. 1995. Racial Nationalism and Its Challengers: Theodore Parker, John Rock, and the Antislavery Movement. Civil War History 41 (2): 142–160.

Tesler, M. 2012. The Spillover of Racialization into Health Care: How President Obama Polarized Public Opinion by Racial Attitudes and Race. American Journal of Political Science 56 (3): 690–704.

Tesler, M. 2016. Post-Racial or Most-Racial?: Race and Politics in the Obama Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tesler, M., and D. Sears. 2010. Obama’s Race: The 2008 Election and the Dream of a Post Racial America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tesler, M. and J. Sides. 2016. “How political science helps explain the rise of Trump: The role of white identity and grievances.” https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/03/03/how-political-science-helps-explain-the-rise-of-trump-the-role-of-white-identity-and-grievances/?utm_term=.d45dd6875623. Accessed 28 December 29, 2016.

Theiss-Morse, E. 2009. Who Counts as an American?. The Boundaries of National Identity: Cambridge; Cambridge University Press.

Thorlakson, L. 2009. Patterns of Party Integration, Influence and Autonomy in Seven Federations. Party Politics 15 (2): 157–177.

Toshkov, D. 2011. Public Opinion and Policy Output in the European Union: A Lost Relationship. European Union Politics 12 (2): 169–191.

Turner, J.C., M.A. Hogg, P.J. Oakes, S.D. Reicher, and M.S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. New York: Basil Blackwell.

Valentino, N., V. Hutchings, and I. White. 2002. Cues that Matter: How Political Ads Prime Racial Attitudes during Campaigns. American Political Science Review 96 (1): 75–90.

van Dyke, N., and S.A. Soule. 2002. “Structural Social Change and Mobilizing Effect of Threat: Explaining Levels of Patriot and Militia Organizing in the United States. Social Problems 49 (4): 497–520.

van Elsas, E., and W. van der Brug. 2015. The Changing Relationship Between Left-Right Ideology and Euroscepticism, 1973–2010. European Union Politics 16 (2): 194–215.

de Vreese, C.H., H.G. Boomgaarden, and H.A. Semetko. 2008. Hard and soft: Public support for Turkish membership in the EU. European Union Politics 9 (4): 511–530.

Williams, C.J. 2016. Issuing Reasoned Opinions: The Effect of Public Attitudes towards the European Union on the usage of the ‘Early Warning System’. European Union Politics 17 (3): 504–521.

Williams, C.J. 2018. Responding Through Transposition: Public Euroskepticism and European Policy Implementation. European Political Science Review 10 (1): 517–570.

Williams, C.J., and S. Bevan. 2019. The Effect of Public Attitudes Towards the European Union on European Commission Policy Activity. European Union Politics 20 (4): 608–628.

Williams, C.J., and J.-J. Spoon. 2015. Differentiated Party Response: The Effect of Euroskeptic Public Opinion on Party Position. European Union Politics 16 (2): 176–193.

Wlezien, C. 1995. The Public as Thermostat: Dynamics of Preferences for Spending. American Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 981–1000.

Wlezien, C. 2004. Patterns of Representation: Dynamics of Public Preferences and Policy. Journal of Politics 66 (1): 1–24.

Zigerell, L.J. 2018. Black and White Discrimination in the United States: Evidence from an Archive of Survey Experiment Studies. Research & Politics 5 (1): 1–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, C.J., Shufeldt, G. How identity influences public attitudes towards the US federal government: lessons from the European Union. Acta Polit 57, 21–51 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00169-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00169-1